Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Doctoral Experience As Researcher Preparation - Gill Turner

Uploaded by

astaroth666-Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Doctoral Experience As Researcher Preparation - Gill Turner

Uploaded by

astaroth666-Copyright:

Available Formats

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/2048-8696.

htm

IJRD 2,1

RESEARCH AND THEORY

46

Received April 2011 Revised May 2011 Accepted May 2011

Doctoral experience as researcher preparation: activities, passion, status

Gill Turner and Lynn McAlpine

Oxford Learning Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Abstract

Purpose Social science doctoral graduates increasingly are moving into higher education research positions yet the nature of these roles is under researched. The purpose of this paper is to compare the experiences of research staff (RS) and doctoral students (DS), to bring an awareness of the extent to which doctoral experience can be preparation for research roles. Design/methodology/approach This research adopts a narrative perspective. Using multi-method data collection the authors compared seven RS and seven DS from the social sciences, capturing their experiences during the rst year of a longitudinal study. Analysis involved developing case summaries and thematic coding. Findings The ndings detail similarities in the work undertaken by each group; show that passionate thought for academic work is rooted early in academic life; and illustrate that status is more complex and uid than previously noted, regardless of role. Research limitations/implications Numbers are small; however, although attrition is a possibility, this longitudinal approach should allow us to explore further our notions of doctoral experience as researcher preparation, as participants move from doctoral study into research positions. Originality/value This is a rare account of a comparison between RS and DS. The paper argues that the experiences of RS are not discrete and specic only to their role but are part of the same journey as that undertaken by DS. Keywords United Kingdom, Higher education, Narratives, Professional education, Career development, Researchers, Doctoral students, Activities, Status, Passion, Preparation Paper type Research paper

International Journal for Researcher Development Vol. 2 No. 1, 2011 pp. 46-60 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 2048-8696 DOI 10.1108/17597511111178014

1. Introduction In recent years, moving into a permanent academic post almost immediately after PhD graduation is no longer the reality. In the UK the proportion of social science PhD graduates nding positions as university lecturers (a role that involves both teaching and research) fell from 39 per cent in 2003 (UK GRAD, 2004), to 34 per cent in 2007 (Vitae, 2009) whilst, at the same time, the proportion entering research staff (RS) roles in higher education rose from 14 per cent (UK GRAD, 2004) to 18 per cent (Vitae, 2009). In the USA, it has been reported that it can take up to ve years before the equivalent of a social science lecturer post is obtained (Nerad et al., 2007). Consequently, for those who desire a permanent academic role it can mean some considerable time post-graduation spent in temporary, xed-term contracts before eventually securing a lecturer post.

With an increasing proportion of social science PhD graduates moving into HE research positions, it is important to explore the nature of the research role. From studies in the 1990s we know about the casualising of research positions, the lack of an effective structure and framework for the career development for such staff, poor management of RS, insecurity of tenure and the knock-on effects of being unable to make long-term denitive plans (e.g. house purchase) which involve nancial support, and the accompanying stresses and dissatisfaction with their situation and perceived lowly status (Sukhnandan, 1997; Allen-Collinson, 1998, 2003, 2004; Shelton et al., 2001). More recent data from the mid-2000s onwards not only conrm these ndings (Wahlberg et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2006; Garforth and Kerr, 2009) but also reveal that RS kerlind, 2009), are are engaged in a diverse and complex range of activities (A passionately committed to their work (McAlpine, 2010), display a wide variation in their kerlind, 2009) and rarely talk of themselves as conceptions of research (Pitcher and A being academics (Akerlind, 2005). Yet, whilst what we know and understand about the nature of research roles is growing, our knowledge and understanding about how researchers are prepared for their role is still minimal. Rather, the literature has focused on preparation for an academic role (Delamont et al., 1994; Golde and Dore, 2001; Bieber and Worley, 2006; Nerad et al., 2007). So, with this as a background, in reality how well might RS have been prepared for their role by their doctoral experience? This paper seeks to answer this question by highlighting some ways in which the experiences of researchers and doctoral students (DS) are similar. By considering the experiences of RS alongside those of DS, we seek to bring an awareness of the extent to which doctoral experiences are actually preparation for research roles in the social sciences. By drawing on different types of data from the rst year of a longitudinal study begun in 2007 we compare RS with DS collectively known as early career academics (ECAs) and report on the activities they engage in, their passion for their work, and their perceptions of their status as an academic. Comparisons between these two groups of academics are scarce and this research shows detailed similarities in the work undertaken by each group: that passionate thought for academic work is rooted early in academic life; and that status is considerably complex and nuanced, and constructed and negotiated regardless of role. These ndings, particularly the last, add to our knowledge and understanding of how doctoral experience may equip RS for their role. Furthermore, we highlight that the experiences of RS are not discrete and specic only to their role but are part of the same journey, though later on, as that undertaken by DS. 2. Methodology Our approach emerges from a narrative perspective; narratives are seen as a way to integrate two aspects of identity construction: the permanence of an individuals perception of personal identity combined with the sense of personal change rather than stability through time (Elliott, 2005). This contrasts with studies mentioned earlier which tend to take phenomenographic or socialisation stances. We recruited 36 ECAs from the social sciences at two research intensive UK universities, comprising 27 DS and nine RS in total. We used a multi-method approach in which individuals provided different forms of narrative. On a monthly basis, over a period of 12-18 months, participants were asked to complete a structured log containing

Researcher preparation

47

IJRD 2,1

48

questions aimed at capturing the activities and experiences of a particular week (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005). Additionally, demographic and biographic questionnaires were distributed and a sub-sample of participants interviewed to gain more detailed understandings of issues arising from the logs. As with previous reports (McAlpine, 2010; McAlpine and Turner, 2010), case summaries were created for each individual through successive re-reading of all data in order to capture a comprehensive, but reduced, narrative (Coulter and Smith, 2009) of individual experience, intention and feeling and to enable the authors to familiarise themselves with each individual. In this process, we noticed similarities in experience across both RS and DS. To substantiate this we selected as case studies for detailed analysis, a subset of individuals who represented the diversity of the group as a whole. This group consisted of seven RS and seven DS from across the two universities, a mix of male and female (though predominantly female) participants, representing UK and international status, several social science elds and different points in their trajectories. Twelve of these 14 had completed between three and 12 logs, whilst one had completed two, and another only one. All were interviewed. Since we already had constructed narratives of the individual cases, we undertook a cross-case analysis (Stake, 2006) to examine activities, passion and status. Detail of the specic analysis is presented in each section; however in general, excerpts relevant to a theme were generated for each individual and then a cross-case analysis was done to generate clusters which were then named as descriptive categories. While what emerged emphasized similarity of experience, there were some differences; we describe any notable ones as we present the ndings. 3. Progression in academic trajectory In terms of their academic progression (Figure 1), individuals varied in their trajectories from early second-year doctoral work (e.g. Nina and James doing upgrades and eldwork during the study) through to second or third research post after graduation (e.g. Paul changing from second to third post and Catherine from second post to her own fellowship). 4. Findings We identied several themes representing similarities between the experiences of RS and DS. Here we report on three of the main themes: what these individuals do, their passion for their work and their status in academia. Since these themes emerged through a cross-case analysis to generate an overall sense of academic practice, this representation is, by necessity, somewhat disembodied, losing the intensity and variation of individual experience. However, it did enable us to see the ways in which different themes were common. 4.1 What they do: the nature of academic work What do academics do? Elizabeth (DS), who grew up with an academic as a father, comments: I never used to know what he did (laughing), so at least now I know exactly what he does! I have a bit more understanding [. . .] It is this mystery we take up here by analyzing the logs. In the logs, participants were specically asked to report the academic-related activities they had engaged in the previous week in two ways:

Transfer

Fieldwork

Upgrade

Submission

Post 1

Post 2

Post 3

Researcher preparation

Nina James Acme Bruno Poppy Elizabeth Hatty Cecilia Jennifer CM KS Chef Paul Catherine

49

Figure 1. Stage of academic progression applicable to each member of the sample

(1) by choosing from a list of possible academic activities (for consistency); and (2) doing a free-write (for variation); the latter (which varied in length) was often written in a chronology and included aspects of the week beyond the academic. To give a sense of these, we include two extensively edited examples which make reference only to academic-related work the focus of this section. The rst is from the log of Nina, a DS, and refers to a week of eldwork on the blues in the USA:

I observed a music class on Monday and Wednesday; chatted with blues educator about music classes; wrote and printed out parental consent forms for children I want to interview at the music class; observed a collegiate blues history class; typed up eld notes; sent out emails; attended a panel discussion on Race in America at the university; and a talk on the history of the citys neighbourhoods and suburbs at a private library; joined the Public Libraries and got books out; read; and went to blues clubs.

The second extract is from the log of Catherine, a researcher:

I worked on a bid for funds. Itll take 5% of my time if successful, but the form-lling is complex and has to be agreed by six organizations in ve countries. I worked on a paper with a colleague and saw two visitors. One had read some of my work and wanted to discuss it; I was a bit cautious because it was a free consultancy, but he was in a position to move my work in useful directions in his part of the world, and he wanted to improve the situation. I gave him some leads and references to other work in my area. The other was an MSc student who came to a talk I gave last month and wanted to know how he might draw on my ideas for his dissertation; and emails, mostly related to the bid.

In order to analyse the types of academic work reported in the logs, cumulative lists were derived for each individual by listing all activities in the logs. Since individuals

IJRD 2,1

50

completed varying numbers of logs, we noted in their own words the presence of an activity, but not the frequency with which it was reported. These individual lists were compared, and categories of activity created in order to be able to compare across individuals. These categories were then clustered into larger groupings and the description of clusters eshed out by additional information reported in the log, since individuals often expanded on the activities they had engaged in elsewhere in the log (for instance, when describing: difculties experienced, the most important individual in supporting their academic work, and individuals interacted with). And, given that we were familiar with the interviews we occasionally supplemented the log information using the relevant interview. The following clusters broadly incorporate the range of activities: . Research and teaching including supervision. . Academic writing and reading. . Networking. . Logistics. . Future employment. 4.1.1 Research and teaching including supervision. We grouped these together since teaching and research are often seen to be core activities for lecturers and had kerlind (2005). Further, we included meeting with the previously been reported by A manager/supervisor since this activity is integral to research for DS and it emerged for RS as well. Research activities. As might be expected, there was more detail about the specics of research than about some other activities. Overall, there was no apparent difference in the nature of the particular activities reported by the two groups. DS doing eldwork had the same sets of relationships to negotiate as RS (e.g. with government ofcials). At the same time, the scope of the projects rather than the activities themselves appeared to become gradually more complex as researchers became more experienced; DS were organizing their own research; newer RS were organizing cross-institutional projects, and the most experienced individual, Catherine (a research fellow), was preparing an EU bid involving multiple institutions in different countries. DS and researchers on fellowships were inherently doing their own research, but those without a fellowship were in a contrary position; by the nature of their employment, they were doing research for others. So several distinguished this research from their own research; for instance, KS referred to going to a seminar and being reminded of the small amount of expertise she held that was outside the narrow scope of her current project. Individuals in both roles often referred to meetings with their supervisors or managers. These were characterised as focused meetings to get feedback or make decisions and often involved prior work on the part of the individual. Individuals in both roles were mindful of using this time with the supervisor/manager well. This involved not only respecting the supervisors/managers knowledge but also not wishing to appear as lacking in independence. Moreover, the relationships, regardless of role or degree of experience, were not without tensions. One researcher, Paul, noted that his manager had been away for four weeks so that he could not draw on the expertise that he needed for a project that was not his. A DS, Poppy, had co-supervisors who had

different opinions; earlier in the process this had been useful, but was no longer so as the submission date approached. Teaching and supervising. Both DS and RS reported teaching, and often enjoying it. Similar to reports of research, these were often quite detailed from preparation of handouts to assessment. Two of the DS and three RS were also supervising postgraduates. This was intriguing given that this would be contrary to most universities policies, so we assume these instances were likely co- or informal supervisions. At least one commented on the value of co-supervision. 4.1.2 Academic writing and reading. Individuals in both roles described a range of types of writing, including genres we consider academic (e.g. funding proposals) and other every-day forms of institutional communication, (e.g. emailing and form lling). We focus here on writing connected to developing their intellectual contributions. Unsurprisingly, a key focus of writing for DS was whatever rite of passage they were experiencing, be that transfer/upgrade, conrmation, or nal submission. Interestingly, RS reported writing for different audiences: brieng for their research groups, progress reports for funders, or recommendations for external audiences. DS reported authoring and co-authoring papers, but not to the same extent as RS who were, depending on how recently they had graduated, trying to publish their doctoral work as well as their current projects. Difculties around writing were expressed by individuals in both roles; for instance, structuring and focusing writing, imagining future publications, trying to write but having little dedicated time, responding to negative feedback, lacking discipline. A key nding, we believe (since such activity is rarely reported), is that nearly all individuals were searching for relevant literature, and reading and making notes as they tried to get a sense of what was relevant in the eld. Difculties regarding reading included: uncertainty/lack of knowledge about theories in the eld (due to coming from a different background); needing to do more reading of theories to clarify thinking. It was notable that only the most experienced researcher reported evaluating and critiquing others academic writing: journal manuscripts, Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) proposals and reports, national trials. One can assume that these tasks are a mark of the recognition of the individuals contribution to the eld. 4.1.3 Networking. All reported face-to-face networking in different contexts (e.g. workshop/seminar/course/conference participation or attendance, as well as more informal contacts). And many had extensive networks. Individuals were asked to describe in their logs the most important individual in the week. In looking across all logs we saw: research participants, supervisor, line manager, other academics and researchers in a range of venues, research group, peers, friends, spouse, those in private or non-governmental organisation (NGO) sectors related to the area of inquiry, etc. As with research, the scope of the networking expanded over time as individuals had more opportunities to meet others and became more recognised for their expertise. For beginning DS relationships tended to be with student peers and within their own institutions, whereas with more advanced DS and new RS the scope extended to include contacts in other institutions nationally, whilst the most experienced had extensive international networks. While networking was seen as a way to advance ones intellectual development, it also was perceived to bear fruit in the job search; Poppy (DS), for instance, went to a conference in London to be introduced to people since he was starting to think more about what I want to do post study. The extent of

Researcher preparation

51

IJRD 2,1

52

an individuals network had implications for moving as well; KS (RS) was concerned about to move back to her home in the US since her academic network there was not as developed as in the UK. A number of individuals were volunteering their expertise to individuals or organisations whose work they valued (e.g. Engineers without Borders). Thus, they were offering their expertise but also expanding their networks, and while consultancies were not reported by a majority of individuals, they were reported by DS and RS equally. Again, this expanded personal networks and, in the instances reported, the expertise was linked to policy debates. 4.1.4 Logistics. Logistics loomed large for all participants. It could be as critical as the DS who needed to ensure his/her eldwork started on a good footing, or as mundane as the day-to-day needs noted by RS. Several individuals reported that one of the things they did was general planning or reviewing how best to organise tasks, likely essential to managing the range of tasks that individuals are expected to complete relatively independently. 4.1.5 Future employment. While all participants thought about future employment, DS early in their degree tended to think of these in the abstract, the imagined career, incorporating an amalgam of what they valued and enjoyed (McAlpine and Turner, 2010). However, for those nearing the end, looking ahead to life after the DPhil, as Poppy expressed it, became more concrete with job seeking going on while writing the thesis: one, for instance, referred to the lack of jobs related to his area and expectations, and another to going for job interviews to avoid a long gap between handing in and starting work (Hatty). Like those nearing the end of the PhD, RS were aware of the job market, seeking to secure further employment before their current contract expired and noting the challenge of ensuring time for writing and publication of their own work while doing anothers research. This analysis has demonstrated the immense number of activities that DS as well as RS engaged in three of which: teaching, supervision, and consultancies are not necessarily viewed as falling within the purview of doctoral or research work (though kerlind (2005) for researchers). We found the similarities in the previously reported by A nature of their work striking; there were no differences as such in the practices they engaged in, rather an increasing complexity, volume and awareness, probably a natural result of where they were in their trajectories. 4.2 Their passion for their work Whilst reading through the log and interview data, we were struck by the way individuals spoke about their work. We saw that DS and RS alike referred to their work in ways that passionately expressed both a high engagement with, and a deep commitment to, what they were involved in. To analyse this in more detail we noted the emotive and motivational words used by these individuals in relation to their work and the contexts within which these words were found. We then coded these into categories. We further scrutinised the categories for the extent to which there were commonalities in the comments made by DS and RS. As a result we observed that the two groups were particularly engaged with, and committed to, their work in terms of satisfaction, in particular as it derived from intellectual stimulation, and making a contribution as described below.

4.2.1 Satisfaction. Individuals in both roles enthusiastically described the overall satisfaction they derived from their work. They expressed how they were really enjoying it (KS, RS); that it was enormously rewarding, amazing, and attractive (Cecilia, RS); it was something they absolutely wanted to do (Hatty, DS) and were passionate about (Jennifer, RS). Their whole engagement in their work seemed underpinned by this sense of fullment Im just delighted to get paid to do something I enjoy doing (Catherine, RS) which, at times, was all consuming: This [my PhD] is my life!! (James, DS). This sense of satisfaction seemed to be derived from intellectual stimulation and making a contribution. Intellectual stimulation. All individuals relished the intellectual stimulation provided by their work. Their research was attractive [. . .] a huge challenge from many different points of view [. . .] social, environmental [. . .] business [. . .] policy providing a professional opportunity to be one of those specialists at the top (Bruno, DS); it was fascinating, bringing together so many issues in the same place[. . .] You really do feel at times like the one-eyed person in the country of the blind (Catherine, RS). They became excited about particular issues I would like to know more about (KS, RS) and were interested to see how the focus might shift (Nina, DS). They had a keen interest in their research topic and remained committed because they found it satisfying[. . .] challenging[. . .] intriguing (Catherine, RS). Making a contribution. Many of the researchers and DS desired to make a contribution. Sometimes this was perceived in terms of social impact, such as wanting to ensure that what Im doing is going to have some practical utility (Acme, DS), and becoming very excited when they were able to capture their [participants] problems[. . .] bring their expertise to bear on the work that they are doing (Cecilia, RS). On other occasions this was perceived in terms of academic impact as in I like the fact that [my area of research] is not heavily investigated, so I can say something meaningful and new (CM, RS) or expressing the importance of presenting at conferences as a chance to put my work in the public domain (Poppy, DS). They viewed their involvement in research for the benet of others as well as for themselves. It is evident from this analysis that DS and researchers alike have a passion for their research as reported in earlier work (McAlpine and Amundsen, 2009; McAlpine, 2010). Clearly it is something they want to do and to which they are dedicated. This seemed to be increasingly the case as they became more experienced and involved in their research areas. 4.3 Their status in academia When status as an academic is referred to in the literature on RS it is usually in negative terms, making reference to their situation as marginalised (Allen-Collinson, 2004; Garforth and Kerr, 2009). This has been conceived in respect of other members of staff and students perceiving them differently (Sukhnandan, 1997); through being excluded from certain activities (e.g. the Research Assessment Exercise[1], (Shelton et al., 2001)); by the temporary nature of their contract, and inferior material (e.g. salary, pensions, accommodation) and symbolic considerations (e.g. lack of a staff email account, exclusion from social events, (Allen-Collinson, 2004)). With this in mind, we were interested in how our participants viewed their status as academics: what did they suppose was their position or standing in relation to others, where did they perceive

Researcher preparation

53

IJRD 2,1

54

themselves to t in the academic community in which they worked, what value did they consider themselves to have as academics? We accessed this information from: . the logs which we sent to participants, where individuals were asked to report examples of an event or experience in which they felt like an academic or that they belonged to an academic community, and examples of where this was not the case; and . from their perceptions of their status in academia contained in the interviews. To analyse the data a list was created for each individual containing the comments they had made which we considered related to academic status. These lists were compared in order to see what, if anything, the various comments had in common across individuals. This led to the creation of a number of categories which we clustered into two broad groupings of references to, or expressions of, a sense of institutional and interpersonal academic status. From this analysis we noted two things among both RS and DS: rst, a wide range of indicators was used to dene status, and, second, positive as well as negative positions of status were expressed. In short, the representation of status in our data appeared more complex and nuanced than has been noted elsewhere. Below we report on the various indicators mentioned and quote some positive and negative examples from the participants. 4.3.1 How they dene their status. Institutional references to status. A number of references made by individuals concerned what we have characterised as their associations with the bodies, practices and hierarchies how the academic community is constructed and construed, specically, the locations or spaces in which DS and researchers work or situate themselves (bodies), the work in which they are engaged (practices), and the attributes which appear to have an acknowledged or inherent rank order (hierarchies). In relation to bodies, DS and researchers dened their status in respect of the locations or spaces in which academics work or situate themselves. Particular reference was made to cultural, disciplinary and organisational aspects, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively, as illustrated below. Culturally, individuals determined their position through comparisons of different international systems of research and academic endeavour. This saw individuals evaluating the countries and institutions in which they worked, and consequently their own status within the system, according to whether: the academic approach was theoryor practice-based, academia was collegial or hierarchical, and track to tenure was exible or rigid:

I started to enjoy that very much in the UK, that it was more of a team, and less of this hierarchical way. I got more of a feeling of belonging to an academic community than I ever got in [other country] (Hatty, doctoral student).

In disciplinary terms, how individuals felt valued as an academic depended on whether their discipline was perceived by others to have cachet, to produce good quality research, or even to exist!

When I started my studies I was heavily engaged in the [X discipline]. I was always more interested in [X discipline]. When I did my PhD I thought should I do it in Sociology or [X discipline] and my professor said Are you stupid?! Just look how many job offers there are for Sociology and for [X discipline], theres no such thing as [X discipline] forget it! Nobody

wants an [X discipline] scientist. Although we were an [X discipline] department, where I was working, all professors there said this (Paul, research staff).

Researcher preparation

Organisations and locations in which individuals worked were endowed with varying degrees of prestige or relevance which was then perceived to reect on an individuals sense of status:

I felt like an academic when working in the British Library. Its a prestigious place (Nina, doctoral student).

55

With regard to practices, individuals related status to the opportunities to engage in the kind of work that academics are perceived to undertake, and they referred to it in predominantly positive terms. For instance, undertaking teaching can validate and elevate their position through contributing to the wider academic endeavour, as Cecilia (RS) noted:

This week the most signicant experience inuencing my feeling of being an academic was teaching. I felt I could share my knowledge and ideas, answering questions and helping other colleagues.

Others saw dissemination such as attending or contributing to workshops, lectures or seminars as providing opportunities to be collegiate, to feel like professionals, to belong to academia. Yet presenting at conferences or writing reviews or articles exposed them and their work to the possibility of afrmation and acceptance from what they perceived to be the wider, more inuential, and more highly respected academic world:

I felt I belonged to an academic community when giving a presentation at a conference. It was a chance to put my work into the public domain (Poppy, doctoral student).

Status in relation to hierarchies was mentioned by DS and researchers alike in respect of the roles ascribed to academics and credentials held by academics. Sometimes this was positively perceived, occasionally it was negatively perceived. Most was said in relation to the roles undertaken by academics, and individuals displayed a keen sense of where they considered themselves to t within a clearly perceived pecking order in role or job title from undergraduate, upwards through masters student, DS, contract researcher, fellow, to lecturer:

At some point I guess, I will become her [my supervisors] colleague, once I obtain my degree [PhD], and Im not going to be the student anymore, so I will be just like her, a research person (Bruno, doctoral student).

Sometimes a degree of nuance was expressed within a perceived level, sometimes a particular level was dismissed out of hand:

I wouldnt like to see myself as a post-doc; I would like to see myself as a researcher, because post-doc seems like in between all the time, that youre still searching for [a] position (CM, research staff).

Credentials academic or professional qualications, or expertise were perceived as a form of stepping stone or barrier to a sense of status or worth; the higher the level of credentials the more of an edge an individual would claim, whilst the lack thereof usually detracted from a sense of academic status:

There are two basic drivers of my insecurity and one is being in the academic context without having a PhD. I try to take advantage of things that are available for what are called early

IJRD 2,1

career academics and realise that I dont quite qualify because I dont actually have my degree whereas most people do. Being in this environment and not having a PhD I always feel a little bit like Im undercover because Im not a proper academic (KS, research staff).

56

Interpersonal references to status. On a considerable number of occasions DS and researchers expressed their sense of status using what we have termed interpersonal references. These concern status as it is perceived to be acknowledged or created in or through academic and non-academic interactions involving our participants and other individuals. It was perceived negatively and positively. For instance, individuals expected a move up the hierarchical chain (e.g. from DS to post-doc) to result in their being treated differently by ones former supervisors. They expected the relationship to become more collegial with their transition from student to colleague to become more social and less distant:

After having my doctorate, I felt I was at a different stage, and wanted to be treated differently. I was ready to really take my own initiative on the issue, but they [formerly her supervisors now her project leaders] really pointed me, very openly, to the fact, you know, that, in a way, you have to do what they ask you to do here (Cecilia, research staff).

Knowing senior colleagues on rst-name terms and being seen conversing with them not only made participants feel good about themselves but also was perceived as prompting greater respect and recognition from others:

To nd out that as young as I am and an academic is a surprise for most people. Then, Ive been working with the head of one of the schools here and just had a quick chat with him but, you know, it changes the way that people look and interact with you. All of a sudden youre someone to know. Youve just bumped up the social hierarchy because youve talked to the head of school and he knew what your name was. It changes where you sit and whether youre a status person or not ( Jennifer, research staff).

Those who found themselves interacting with non-academics found that the occasion often highlighted the fact that they were academics who belonged to an academic community:

When you talk about your research with other academics it all sort of makes sense because youre talking with other people that are also doing research. Then when I met with the utility company, they had no clue what I was talking about and they wouldnt see the value of doing it. They seemed to put a barrier between academics and practitioners and so that also made me feel like an academic (Acme, doctoral student).

This analysis shows that all individuals perceived their status to be conferred through a broad range of indicators, and in positive and negative ways. It provides a much more complex and nuanced representation of status than previously reported. The grouping of these indicators into institutional and interpersonal factors has been helpful for analytic purposes but it is clear that there is an interaction between the two; there are many instances of status being conferred during interpersonal interactions within academic-related settings, such as we see below:

The signicant event or experience in which I felt like an academic or belonged to an academic community was a publication [request for] an expert journal. Getting feedback from expert people in my eld gives me the feeling to be (sic) on the right track (Hatty, doctoral student).

5. Discussion In the Introduction we observed that little is known about how social science researchers are prepared for the role they undertake, though increasingly it is a research rather than a traditional academic position that follows after PhD graduation. By drawing on the experiences of RS and DS we wanted to see in what ways these roles might be similar. From this analysis we hoped to draw conclusions about how doctoral experience may equip RS for their role. kerlind, 2009) we noted that RS were engaged in a In keeping with other studies (A breadth of work. This diversity covered a range of activities, including those which were not solely related to the research they were doing (e.g. teaching, supervision, consultancy). Furthermore, we found that DS also were engaged in this same range of activities, several of which had no immediate bearing on the development of their thesis. This similarity in the variety of work did not make the two roles identical because of the difference between the two groups in relation to the complexity, volume, and awareness of the work undertaken (e.g. DS in the earlier phases of their studies reported less varied networks and projects of a less multifaceted nature than did researchers with the most experience). However, what this has shown is that, despite their relative newness as academics, these students were taking opportunities to acquire some of the experience and expertise necessary for a potential career in academia. Another similarity between the two groups concerned their passion for their work. Researchers were extremely engaged with, and committed to, their research in ways which suggest a high intrinsic motivation for what they were doing. Clearly, some had spent a number of years developing their topic and expertise, gaining great satisfaction from making an acknowledged contribution to their eld and becoming strongly attached to their work. Likewise, we noted that DS engagement with, and commitment to, their research was underpinned by an enthusiasm for what they were involved in. Although they were just starting out in academia we could see their enjoyment of their research and their desire to have an impact; this was particularly evident among those who had a clear idea of what they wanted to achieve in the long-term. Such passionate thought has been observed before in academics, but mainly in those who are early post-tenure (Neumann, 2006). What our observations suggest, as Neumann mooted, is that this passionate thought for academic work is rooted much earlier in life; here we see DS at the start of their careers and researchers who are further along still pre-tenure displaying emotional reasons for engaging in the work that they do. Turning to our nal theme, in the past, RS have referred to their status mostly in negative terms and mainly by interpreting their positions as perceived by roles and job titles. What we have found here represents a refreshing break from this trend. RS referred to their status in positive as well as negative terms. In relation to the former, many reported a number of occasions when they felt like academics or felt they belonged to an academic community. With a range of indicators being drawn upon to determine their positions, we saw status being dened according to the individuals perspective and not necessarily by that potentially imposed from elsewhere. For instance, their perceptions may emerge from their engagement in the full range of academic activities regardless of their job title; it may also reect a personal re-positioning in the light of an employment context of fewer lecturerships. This perception was mirrored in the experiences of the DS. We observed them in ux about their status, sometimes considering themselves students whilst, most times,

Researcher preparation

57

IJRD 2,1

highlighting occasions when they felt like academics. The conclusion we draw is that status is considerably complex and nuanced, both in doctoral and post-doctoral years. It is not something that is settled or imposed purely by virtue of being either a DS or a researcher; it is something that is constructed and negotiated regardless of role. 6. Conclusion Comparing the experiences of RS with those of DS posed difculties in differentiating between the two groups. We have shown that there are considerable similarities in terms of the activities in which they engage, their passion for their work, and how they view their status as academics. This leads us to make the following remarks about how doctoral education may be a useful basis for undertaking the role of a researcher. First, doctoral study can provide opportunities for students to experience a range of activities which are also undertaken by researchers. Time spent in a research post may then provide the opportunity for the complexity, volume and awareness of these activities to be developed. In turn, perhaps this experience better prepares the researcher for the role of tenured academic with its responsibilities encompassing research, teaching and service. Second, the doctoral years can give students the opportunity to express and explore the passion they have for their research, and to determine how this passion contributes to their motivation for a career in academia. Since passionate thought seems to be a key element of post-doctoral work, it seems crucial that DS develop an enthusiasm for their work if they aspire to remain in academia. Whether as a researcher or early post-tenured academic, further stimulation and maturation of this passion is an integral part of these roles; individuals with a clear sense of this in their doctoral years may be better prepared for their post-doctoral careers. Finally, the doctoral experience provides students with one of their earliest opportunities to establish whether they might t into academia. It can bring them into contact with a variety of ways to dene whether they think they are, or are not, an academic and introduce them to the notion that status can be what you make it. This is perfect preparation for a position as a researcher where individuals frequently seek and negotiate a sense of academic belonging. In conclusion, we suggest that there is much about being a DS which is good preparation for becoming a social science researcher. In fact, it could be said that the experiences of RS are part of the same journey as that being embarked upon by DS.

Note 1. The Research Assessment Exercise (RAE; www.rae.ac.uk) is an explicit and formalised assessment process of the quality of research carried out in UK universities. It is the principal means by which institutions assure themselves of the quality of the research undertaken in the Higher Education sector. Six such exercises have taken place since 1986. From 2014 the RAE will be replaced by the Research Excellence Framework (REF; www.hefce.ac.uk/ research/ref/). References Agosto, D. and Hughes-Hassell, S. (2005), People, places, and questions: an investigation of the everyday life information-seeking behaviours of urban young adults, Library & Information Science Research, Vol. 27, pp. 141-63.

58

kerlind, G. (2005), Postdoctoral researchers: roles, functions and career prospects, Higher A Education Research and Development, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 21-40. Akerlind, G. (2009), Postdoctoral research positions as preparation for an academic career, International Journal for Researcher Development, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 84-96, available at: http://dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/224920 (accessed 22 February 2011). Allen-Collinson, J. (1998), Capturing contracts: informal activity among contract researchers, British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 497-515. Allen-Collinson, J. (2003), Working at a marginal career: the case of UK social science contract researchers, The Sociological Review, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 405-22. Allen-Collinson, J. (2004), Occupational identity on the edge: social science contract researchers in higher education, Sociology, Vol. 38, pp. 313-29. Bieber, J.P. and Worley, L.K. (2006), Conceptualizing the academic life: graduate students perspectives, Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 77 No. 6, pp. 1009-35. Coulter, C. and Smith, M. (2009), The construction zone: literary elements in narrative research, Educational Researcher, Vol. 38 No. 8, pp. 577-90. Delamont, S., Parry, O., Atkinson, P. and Hiken, A. (1994), Suspended between two stools: doctoral students in British higher education, in Coffey, A. and Atkinson, P. (Eds), Occupational Socialization and Working Lives, Avebury, Aldershot, pp. 138-53. Elliott, J. (2005), Using Narrative in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, Sage, London, UK. Garforth, L. and Kerr, A. (2009), Constructing Careers, Creating Communities: Findings of the UK KNOWING Research on Knowledge, Institutions and Gender, available at: http://knowing.soc.cas.cz/static/article/data205/les/constructing_careers__creating_ communities.pdf (accessed 14 March 2011). Golde, C.M. and Dore, T.M. (2001), At Cross Purposes: What the Experiences of Todays Doctoral Students Reveal About Doctoral Education, Pew Charitable Trusts, Philadelphia, PA. Lee, T., Fuller, A., Bishop, D., Felstead, A., Jewson, N., Kakavelakis, K. and Unwin, L. (2006), Reconguring contract research? Career, work and learning in a changing employment landscape, paper presented at the SRHE Conference, 12th-14th December, Brighton, available at: http://learningaswork.cf.ac.uk/outputs/SRHE_Conf_paper.pdf (accessed 22 February 2011). McAlpine, L. (2010), Fixed-term researchers in the social sciences: passionate investment, yet marginalizing experiences, International Journal for Academic Development, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 229-40. McAlpine, L. and Amundsen, C. (2009), Identity and agency: pleasures and collegiality among the challenges of the doctoral journey, Studies in Continuing Education, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 107-23. McAlpine, L. and Turner, G. (2010), Imagining and emerging career patterns: perceptions of doctoral students and research staff, paper presented at the SRHE Conference 14-16 December, Newport, available at: http://srhe.ac.uk/conference2010/abstracts/0158.pdf (accessed 22 February 2011). Nerad, M., Rudd, E., Morrison, E. and Picciano, J. (2007), Social Science PhDs Five Years and Out: A National Survey of PhDs in Six Field, University of Washington Center for Innovation and Research in Graduate Education, Seattle, WA. Neumann, A. (2006), Professing passion: emotion in the scholarship of professors at research universities, American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 43 No. 3, pp. 382-424.

Researcher preparation

59

IJRD 2,1

60

kerlind, G. (2009), Post-doctoral researchers conceptions of research: Pitcher, R. and A a metaphor analysis, International Journal for Researcher Development, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 42-56, available at: http://dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/224927 (accessed 22 February 2011). Shelton, N., Laoire, C.N., Fielding, S., Harvey, D.C., Pelling, M. and Duke-Williams, O. (2001), Working at the coal-face: contract staff, academic initiation and the RAE, Area, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 434-9. Stake, R. (2006), Multiple Case Study Analysis, The Guilford Press, New York, NY. Sukhnandan, L. (1997), Indispensable but under-valued: the exploitation of contract research staff, Teaching in Higher Education, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 333-9. UK GRAD (2004), What do PhDs do?, available at: http://vitae.ac.uk/CMS/les/1.UKGRADWDPD-full-report-Sep-2004.pdf (accessed 7 March 2011). Vitae (2009), What do researchers do? First destinations of doctoral students by subject 2003-2007, available at: http://vitae.ac.uk/CMS/les/upload/Vitae-WDRD-by-subject-Jun09.pdf (accessed 7 March 2011). Wahlberg, M., Diment, K., Davies, J., Colley, H. and Wheeler, E. (2004), Underground working Types of silence, paper presented at the RCBN Contract Researchers and Early Career Conference, 2nd-3rd December, Edinburgh. About the authors Gill Turner is a Researcher in higher education based at the Oxford Learning Institute, University of Oxford, UK. She is currently engaged in research into the experiences of early career academics, in particular doctoral students, research staff and new supervisors. Gill Turner is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: gill.turner@learning.ox.ac.uk Lynn McAlpine is Professor of Higher Education Development at the University of Oxford, UK. She has received distinguished research awards from both the American Educational Research Association and the Canadian Society for Studies in Higher Education. Her present research, done in collaboration with research teams in the UK and Canada, examines how doctoral students, research staff and new lecturers are experiencing and trying to make sense of the multiple and shifting demands of academic work.

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

You might also like

- 3 - Nash, Mary - pp.123-150Document18 pages3 - Nash, Mary - pp.123-150astaroth666-No ratings yet

- Education Policy France Socialist YearsDocument9 pagesEducation Policy France Socialist Yearsastaroth666-No ratings yet

- La Jornada Maya - K'IintsilDocument2 pagesLa Jornada Maya - K'Iintsilastaroth666-No ratings yet

- Analyzing Social Settings - LoflandDocument44 pagesAnalyzing Social Settings - Loflandastaroth666-100% (4)

- Posdoctoral Researchers - Roles Functions and Career Prospects - Gerlese S AkerlinDocument21 pagesPosdoctoral Researchers - Roles Functions and Career Prospects - Gerlese S Akerlinastaroth666-No ratings yet

- Global-Education Roger DaleDocument298 pagesGlobal-Education Roger Daleastaroth666-No ratings yet

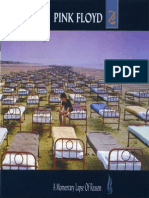

- Pink Floyd - A Momentary Lapse of ReasonDocument9 pagesPink Floyd - A Momentary Lapse of Reasonastaroth666-No ratings yet

- Manual HP Veer 4gDocument278 pagesManual HP Veer 4gastaroth666-No ratings yet

- Pink Floy - The Final Cut PDFDocument7 pagesPink Floy - The Final Cut PDFastaroth666-0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Assignment 1 PDFDocument5 pagesAssignment 1 PDFAyesha WaheedNo ratings yet

- Daftar BukuDocument6 pagesDaftar Bukuretnopamungkas55yahoNo ratings yet

- Identification of The Challenges 2. Analysis 3. Possible Solutions 4. Final RecommendationDocument10 pagesIdentification of The Challenges 2. Analysis 3. Possible Solutions 4. Final RecommendationAvinash VenkatNo ratings yet

- CBQ - Leadership and Management in Nursing 2009Document14 pagesCBQ - Leadership and Management in Nursing 2009Lizette Leah Ching95% (20)

- Chapter 9 Decision Making Under UncertaintyDocument15 pagesChapter 9 Decision Making Under UncertaintyjalilacastanoNo ratings yet

- Data Communications: ECE 583 LectureDocument6 pagesData Communications: ECE 583 Lecturechloe005No ratings yet

- WHP English10 1ST QDocument8 pagesWHP English10 1ST QXhiemay Datulayta CalaqueNo ratings yet

- How GE Is Disrupting ItselfDocument2 pagesHow GE Is Disrupting ItselfAdithya PrabuNo ratings yet

- A Survey On Existing Food Recommendation SystemsDocument3 pagesA Survey On Existing Food Recommendation SystemsIJSTENo ratings yet

- English - Chapter 6 - The Making of A Scientist - Junoon - English - Chapter 6 - The Making of A Scientist - JunoonDocument10 pagesEnglish - Chapter 6 - The Making of A Scientist - Junoon - English - Chapter 6 - The Making of A Scientist - JunoonSaket RajNo ratings yet

- Roma and The Question of Self-DeterminationDocument30 pagesRoma and The Question of Self-DeterminationvictoriamssNo ratings yet

- Kpi MR Qa QC SheDocument38 pagesKpi MR Qa QC SheAhmad Iqbal LazuardiNo ratings yet

- Solar TimeDocument3 pagesSolar TimeAkshay Deshpande0% (1)

- Design of A Full Adder Using PTL and GDI TechniqueDocument6 pagesDesign of A Full Adder Using PTL and GDI TechniqueIJARTETNo ratings yet

- Laws of ReflectionDocument3 pagesLaws of ReflectionwscienceNo ratings yet

- Theme of Otherness and Writing Back A Co PDFDocument64 pagesTheme of Otherness and Writing Back A Co PDFDeepshikha RoutrayNo ratings yet

- Newest CV Rhian 2016Document2 pagesNewest CV Rhian 2016api-317547058No ratings yet

- Monograph 33Document106 pagesMonograph 33Karthik Abhi100% (1)

- Ward Wise Officers ListDocument8 pagesWard Wise Officers ListprabsssNo ratings yet

- Assignment Gravity and MotionDocument23 pagesAssignment Gravity and MotionRahim HaininNo ratings yet

- Exam 1Document61 pagesExam 1Sara M. DheyabNo ratings yet

- Schnugh V The State (Bail Appeal) Case No 92-09 (Van Niekerk & Parker, JJ) 31jan'11 PDFDocument25 pagesSchnugh V The State (Bail Appeal) Case No 92-09 (Van Niekerk & Parker, JJ) 31jan'11 PDFAndré Le RouxNo ratings yet

- Crane Duty Rating Chart - LatestDocument9 pagesCrane Duty Rating Chart - LatestAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- Assignment 4. A Boy Wizard.Document5 pagesAssignment 4. A Boy Wizard.Jalba eudochiaNo ratings yet

- Automatic Garbage Collector Machine: S. A. Karande S. W. Thakare S. P. Wankhede A. V. SakharkarDocument3 pagesAutomatic Garbage Collector Machine: S. A. Karande S. W. Thakare S. P. Wankhede A. V. Sakharkarpramo_dassNo ratings yet

- JD of HSE LO MD Abdullah Al ZamanDocument2 pagesJD of HSE LO MD Abdullah Al ZamanRAQIB 2025No ratings yet

- Problem Sheet V - ANOVADocument5 pagesProblem Sheet V - ANOVARuchiMuchhalaNo ratings yet

- MOUNTAINDocument8 pagesMOUNTAINlara_sin_crof6873No ratings yet

- (1997) Process Capability Analysis For Non-Normal Relay Test DataDocument8 pages(1997) Process Capability Analysis For Non-Normal Relay Test DataNELSONHUGONo ratings yet

- Atv DVWK A 281 e LibreDocument25 pagesAtv DVWK A 281 e LibrerafapoNo ratings yet