Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chinaperspectives 5833 2012 1 Julia Lovell The Opium War Drugs Dreams and The Making of China

Uploaded by

Sam KeaysOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chinaperspectives 5833 2012 1 Julia Lovell The Opium War Drugs Dreams and The Making of China

Uploaded by

Sam KeaysCopyright:

Available Formats

China Perspectives

2012/1 (2012) China's WTO Decade

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Xavier Pauls

Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China

Basingstoke/Oxford, Picador, 2011, 458pp.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Warning The contents of this site is subject to the French law on intellectual property and is the exclusive property of the publisher. The works on this site can be accessed and reproduced on paper or digital media, provided that they are strictly used for personal, scientific or educational purposes excluding any commercial exploitation. Reproduction must necessarily mention the editor, the journal name, the author and the document reference. Any other reproduction is strictly forbidden without permission of the publisher, except in cases provided by legislation in force in France.

Revues.org is a platform for journals in the humanites and social sciences run by the CLEO, Centre for open electronic publishing (CNRS, EHESS, UP, UAPV).

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Electronic reference Xavier Pauls, Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China, China Perspectives [Online], 2012/1|2012, Online since 30 March 2012, connection on 10 December 2013. URL: http:// chinaperspectives.revues.org/5833 Publisher: French Centre for Research on Contemporary China http://chinaperspectives.revues.org http://www.revues.org Document available online on: http://chinaperspectives.revues.org/5833 Document automatically generated on 10 December 2013. The page numbering does not match that of the print edition. All rights reserved

Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China

Xavier Pauls

Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China

Basingstoke/Oxford, Picador, 2011, 458pp.

Number of pages in print edition : p. 75-76 Translated by N. Jayaram

1

Opium is one of the most bandied about subjects in Chinese history, and the specialist would learn little that is new in this study, which is mainly a (good) synthesis of existing works. The main value added in this book lies in its offering of a larger perspective that more pointed research tomes often lose sight of. We learn that the First Opium War (1839-1842) was actually of secondary importance in the eyes of contemporaries. The Qing dynasty faced threats (revolts and natural calamities) that its administrative elite deemed more serious for its very survival. In London, the frustrations of the far-off military operations came in handy as tools for internal political wrangling in parliamentary debates. The author rightly points out the extent to which the British Empires engagement in the war was marked by improvisations, hesitations, and pangs of conscience, so much so that it was far from having a precise or well thought-out plan of imperialist conquest. This is by no means a superfluous lesson for the historian, often given to attributing a posteriori coherence to a series of events. Lovell has taken pains to present a series of lively and precise portraits of the major protagonists of the First Opium War such as the Emperor Daoguang, imperial commissioner Lin Zexu and his Manchu successor Qishan, and on the British side, foreign secretary Lord Palmerston and Chief Superintendent of the China trade Charles Elliot. It is a judicious choice, considering that distance conferred on the actors on the ground much freedom of action: it should be borne in mind that for the British forces, the operation theatre was many months voyage from the mother country. Thus, the replacement in May 1841 of Elliot (rather inclined towards conciliation) by the intransigent Henry Pottinger represented a real turning point in the war. From then on, the British expeditionary force turned ruthless in using its crushing military superiority to force a speedy agreement. This was the famous Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing), hammered out under extraordinary conditions. Lovell describes over some wonderful pages the poker game between Pottinger and the Emperors two emissaries, Qiying and Yilibu, highlighting the role of the obscure Zhang Xi, personal secretary of Yilibu. As the title indicates, the First Opium War takes up two thirds of the book, and the Second (1856-1860) is dealt with in much less detail. The final chapters show how late nineteenth century intellectuals such as Yan Fu literally invented the Opium Wars (until then, historiographers did not label them as such, simply referring to border skirmishes). Finally, Lovell presents interesting elements regarding the privileged place accorded to the Opium Wars in the current historic orthodoxy. She stresses that it is only since the late twentieth century that the wars have gained primacy in school curricula and official rhetoric in the Peoples Republic of China. Following the Tiananmen massacre, the Communist Party had the brilliant idea of exploiting the anniversary of the 150-year-old opium wars to deflect public wrath towards an external enemy imperialism. To the readers delight, Lovell has produced a clear, agreeable, and lively account. Some lengthy passages could have been shortened, especially descriptions of the horrors of different military operations, as well as discussions of the appalling hacks pushing the Yellow Peril thesis (pp. 274-291). It is regrettable that Lovell seems to be unaware (but then again, unfortunately, so is a near totality of opium historians) that the routinely reproduced photographs of opium smokers in the late Qing are just studio jobs meant to fuel a flourishing picture postcard industry presenting a rather spurious exoticism. It is thus futile to theorise as

China Perspectives, 2012/1 | 2012

Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China

she does over the degree of addiction and even more over the feelings of smokers from the time the clich caught on (p. 17). She may also be accused of some lack of fair play. While she has read (and generously used) the best of historiography in English on the subject, she rarely mentions a few older academic works in Chinese. It is regrettable that some excellent accounts of the history of opium, such as the one by Wang Hongbin, have been ignored. While it may not necessarily have been the authors intent, the book gives the impression that all Chinese historians today adhere to the totally grotesque official interpretation of the Opium War aimed at the larger public. References Electronic reference

Xavier Pauls, Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China, China Perspectives [Online], 2012/1|2012, Online since 30 March 2012, connection on 10 December 2013. URL: http://chinaperspectives.revues.org/5833

Bibliographical reference Xavier Pauls, Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China, China Perspectives, 2012/1|2012, 75-76.

Author

Xavier Pauls Assistant Professor at EHESS, Paris.

Copyright All rights reserved

China Perspectives, 2012/1 | 2012

You might also like

- Louis XVI - The Silent King 9780340706497Document241 pagesLouis XVI - The Silent King 9780340706497Aleksandar Nešović100% (3)

- Unknown Quantity A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra - John DerbyshireDocument391 pagesUnknown Quantity A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra - John DerbyshireEdion Petriti100% (1)

- Unknown Quantity A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra - John DerbyshireDocument391 pagesUnknown Quantity A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra - John DerbyshireEdion Petriti100% (1)

- Zelda 5E Master's GuideDocument41 pagesZelda 5E Master's GuideFelipe Figueiredo67% (3)

- Wasted HackDocument1 pageWasted HackTravis ThompsonNo ratings yet

- The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern ChinaFrom EverandThe Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern ChinaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- Who Set Hitler Against StalinDocument352 pagesWho Set Hitler Against Stalinzli_zumbul100% (1)

- The People's Flag: The Union of Britain and the Kaiserreich: The People's Flag, #1From EverandThe People's Flag: The Union of Britain and the Kaiserreich: The People's Flag, #1Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Still No Black in The Union Jack?: Join Our Mailing ListDocument7 pagesStill No Black in The Union Jack?: Join Our Mailing ListMichael TheodoreNo ratings yet

- Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque - The Living, Dead, and UndeadDocument386 pagesAbsolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque - The Living, Dead, and UndeadEmilio Vicente100% (1)

- Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with JapanFrom EverandEagle Against the Sun: The American War with JapanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (108)

- Speaking to History: The Story of King Goujian in Twentieth-Century ChinaFrom EverandSpeaking to History: The Story of King Goujian in Twentieth-Century ChinaNo ratings yet

- A Method For The Dbign of Ship' Propulsion Shaft Systems. William e Lehr, Jr. Edwin L ParkerDocument212 pagesA Method For The Dbign of Ship' Propulsion Shaft Systems. William e Lehr, Jr. Edwin L Parkerramia_30No ratings yet

- Complaint and Jury Demand + Exhibit ADocument39 pagesComplaint and Jury Demand + Exhibit ASusan GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Robert CapaDocument3 pagesRobert Capaly miNo ratings yet

- 0165-12 Nato GuideDocument688 pages0165-12 Nato GuideDaniel Stanescu100% (3)

- NHD1617 Ann BibDocument10 pagesNHD1617 Ann BibAlex LinNo ratings yet

- The Moscow Option: An Alternative Second World WarFrom EverandThe Moscow Option: An Alternative Second World WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- Victorian Literature and Postcolonial Studies, by Patrick BrantlingerDocument4 pagesVictorian Literature and Postcolonial Studies, by Patrick BrantlingerMaulic ShahNo ratings yet

- Rise of the Tang Dynasty: The Reunification of China and the Military Response to the Steppe Nomads (AD 581-626)From EverandRise of the Tang Dynasty: The Reunification of China and the Military Response to the Steppe Nomads (AD 581-626)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Sex and ViolenceDocument12 pagesSex and ViolenceBruno MaltaNo ratings yet

- Dissentient Judgement of R.B. Pal, Tokyo TribunalDocument504 pagesDissentient Judgement of R.B. Pal, Tokyo Tribunaldeathknoll100% (1)

- Waterloo: The Truth At Last: Why Napoleon Lost the Great BattleFrom EverandWaterloo: The Truth At Last: Why Napoleon Lost the Great BattleRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Pound, Ezra - On The Protocols PDFDocument4 pagesPound, Ezra - On The Protocols PDFLucas AlvesNo ratings yet

- The Cold War and After: Capitalism, Revolution and Superpower PoliticsFrom EverandThe Cold War and After: Capitalism, Revolution and Superpower PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Chapter7 ReadingDocument2 pagesChapter7 Reading013AndreeaNo ratings yet

- (04a) BOOK REVIEWSDocument5 pages(04a) BOOK REVIEWSbeserious928No ratings yet

- Effects of The First World War On LiteratureDocument16 pagesEffects of The First World War On LiteratureammagraNo ratings yet

- Stalin’s Vengeance: The Final Truth About the Forced Return of Cossacks After World War IIFrom EverandStalin’s Vengeance: The Final Truth About the Forced Return of Cossacks After World War IINo ratings yet

- Stephen Howe (2011) : Flakking The Mau Mau Catchers, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 39:5, 695-697Document4 pagesStephen Howe (2011) : Flakking The Mau Mau Catchers, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 39:5, 695-697TrepNo ratings yet

- The Englishness of English PunkDocument52 pagesThe Englishness of English PunkCláudia PereiraNo ratings yet

- TXTDocument128 pagesTXTAndy WilsonNo ratings yet

- Cold Steel, Weak Flesh Mechanism, Masculinity and The Anxieties of Late Victorian EmpireDocument27 pagesCold Steel, Weak Flesh Mechanism, Masculinity and The Anxieties of Late Victorian Empirelobosolitariobe278No ratings yet

- The Legacies of Two World Wars: European Societies in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandThe Legacies of Two World Wars: European Societies in the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Causes of The Opium WarDocument14 pagesCauses of The Opium WarRitika SinghNo ratings yet

- History of English-Speaking People PDFDocument29 pagesHistory of English-Speaking People PDFIndra SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Study QuestionsDocument7 pagesStudy Questionsjoyful budgiesNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Black, A History of Diplomacy, Reaktion Books: London, 2010 312 Pp. 9781861896964, 20.00 (HBK) 9781861898319, 15.00 (PBK) Reviewed By: Richard Carr, University of East Anglia, UKDocument3 pagesJeremy Black, A History of Diplomacy, Reaktion Books: London, 2010 312 Pp. 9781861896964, 20.00 (HBK) 9781861898319, 15.00 (PBK) Reviewed By: Richard Carr, University of East Anglia, UKJetonNo ratings yet

- Triad HistoryDocument35 pagesTriad Historye441No ratings yet

- AULA 18. THE Opium ProblemDocument17 pagesAULA 18. THE Opium ProblemMaria Leticia de Alencar MachadoNo ratings yet

- Hiatory of BookDocument16 pagesHiatory of BookDragon LafyNo ratings yet

- King Leopold's Ghost by Adam Hochschild - Discussion QuestionsDocument14 pagesKing Leopold's Ghost by Adam Hochschild - Discussion QuestionsHoughton Mifflin Harcourt100% (1)

- Rizal Philippine Nationalist and Martyr by Italicaustin Coatesit 1969Document2 pagesRizal Philippine Nationalist and Martyr by Italicaustin Coatesit 1969River AbisNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For War of The WorldsDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For War of The Worldsstefanieyangmanchester100% (2)

- Documentary History Social MemoryDocument11 pagesDocumentary History Social MemoryDominique JonesNo ratings yet

- Works Cited Primary Sources NewspapersDocument20 pagesWorks Cited Primary Sources Newspapersapi-199755043No ratings yet

- The Knights of Bushido: A History of Japanese War Crimes During World War IIFrom EverandThe Knights of Bushido: A History of Japanese War Crimes During World War IIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- 03 Nam-Lin - HurDocument28 pages03 Nam-Lin - HurAndrew KimNo ratings yet

- New Interventions, Volume 13, No 3Document51 pagesNew Interventions, Volume 13, No 3rfls12802No ratings yet

- Imperialismo UKDocument21 pagesImperialismo UKMiguel Ángel Puerto FernándezNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Journals of L K Little, 1943-54Document2 pagesThe Chinese Journals of L K Little, 1943-54Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Clockwork Dystopian MotifsDocument34 pagesClockwork Dystopian MotifsMachete9812No ratings yet

- (Ebook) - ImperiumDocument324 pages(Ebook) - ImperiumIvan M. BudimirovićNo ratings yet

- The Grand Illusion AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Grand Illusion Analysisapi-354312348No ratings yet

- State of War The Violent Order of Fourteenth-Century JapanDocument5 pagesState of War The Violent Order of Fourteenth-Century JapanAlejandro J. Santos DomínguezNo ratings yet

- 30-Second Napoleon - Charles EsdaileDocument171 pages30-Second Napoleon - Charles EsdaileMauro TomazNo ratings yet

- George Orwell - Wells, Hitler and The World StateDocument7 pagesGeorge Orwell - Wells, Hitler and The World StateMiodrag MijatovicNo ratings yet

- ApeuroDocument11 pagesApeuroapi-288748017No ratings yet

- What Makes A Good HistorianDocument4 pagesWhat Makes A Good Historianchooley1No ratings yet

- Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earthFrom EverandTolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earthRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (100)

- Research Method Assignment 2 Example3Document7 pagesResearch Method Assignment 2 Example3Sam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Quantum DBDocument12 pagesQuantum DBSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- 460705Document20 pages460705Sam KeaysNo ratings yet

- PHD ProposalDocument85 pagesPHD ProposalSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0957417411008475 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0957417411008475 MainSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0167268108001959 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0167268108001959 MainSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Modern Language AssociationDocument4 pagesModern Language AssociationSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- INTRO Spiking Neural Networks An Introduction-VreekenDocument5 pagesINTRO Spiking Neural Networks An Introduction-VreekenZiom TygaNo ratings yet

- Modern Language AssociationDocument4 pagesModern Language AssociationSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- B Splines 04 PDFDocument16 pagesB Splines 04 PDFShawn PetersenNo ratings yet

- Decision Making in A Fuzzy EnvironmentDocument24 pagesDecision Making in A Fuzzy EnvironmentYuliya ZverevaNo ratings yet

- Deterministic PDA: Fall 2003 Costas Busch - RPI 1Document24 pagesDeterministic PDA: Fall 2003 Costas Busch - RPI 1Sam KeaysNo ratings yet

- INTRO Spiking Neural Networks An Introduction-VreekenDocument5 pagesINTRO Spiking Neural Networks An Introduction-VreekenZiom TygaNo ratings yet

- Fuzzy Logic Assignment 1Document21 pagesFuzzy Logic Assignment 1Sam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals CourseworkDocument1 pageFundamentals CourseworkSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Chinaperspectives 5833 2012 1 Julia Lovell The Opium War Drugs Dreams and The Making of ChinaDocument3 pagesChinaperspectives 5833 2012 1 Julia Lovell The Opium War Drugs Dreams and The Making of ChinaSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- DataDocument1 pageDataSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- VerificationDocument18 pagesVerificationSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals CourseworkDocument1 pageFundamentals CourseworkSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy Takeaway Newsletter 68Document9 pagesThe Philosophy Takeaway Newsletter 68Sam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals CourseworkDocument1 pageFundamentals CourseworkSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- De GruyterDocument33 pagesDe GruyterSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Project Profsdfsdposal Push DownDocument7 pagesProject Profsdfsdposal Push DownSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- P Rich Heresy AristotleDocument22 pagesP Rich Heresy AristotleSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Chinaperspectives 5833 2012 1 Julia Lovell The Opium War Drugs Dreams and The Making of ChinaDocument3 pagesChinaperspectives 5833 2012 1 Julia Lovell The Opium War Drugs Dreams and The Making of ChinaSam KeaysNo ratings yet

- Gateway Selection in Rural Wireless Mesh Networks: Team: Lara Deek, Arvin Faruque, David JohnsonDocument24 pagesGateway Selection in Rural Wireless Mesh Networks: Team: Lara Deek, Arvin Faruque, David JohnsonPravesh Kumar ThakurNo ratings yet

- MP5 MM (En) 927 859Document50 pagesMP5 MM (En) 927 859Dzul Effendi100% (1)

- The Story of Ireland by Lawless, Emily, 1845-1913Document228 pagesThe Story of Ireland by Lawless, Emily, 1845-1913Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Savage Westeros PDFDocument32 pagesSavage Westeros PDFCharles HernandezNo ratings yet

- cASHELESS GARAGEDocument364 pagescASHELESS GARAGEbharatNo ratings yet

- Renatus NewDocument36 pagesRenatus NewLalit ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Hoi 5 Assignment 2112102Document7 pagesHoi 5 Assignment 2112102Divya RaniNo ratings yet

- Euis Fiza FauziahDocument4 pagesEuis Fiza Fauziahviktor sandesNo ratings yet

- 2008-02-01 - Egypt-Gaza Border Effect On Israeli-Egyptian Relations 101806 PDFDocument5 pages2008-02-01 - Egypt-Gaza Border Effect On Israeli-Egyptian Relations 101806 PDFapi-26004521No ratings yet

- 7.62x51 Mil ManualDocument37 pages7.62x51 Mil ManualStephenPowersNo ratings yet

- Cleopatra at Four PagesDocument4 pagesCleopatra at Four Pagesanon-7879100% (1)

- Federal Jobs IN Alabama: Redstone Arsenal Huntsville Madison CountyDocument12 pagesFederal Jobs IN Alabama: Redstone Arsenal Huntsville Madison Countyalison carrNo ratings yet

- PrelimsDocument6 pagesPrelimscolkent22No ratings yet

- Who Are The Main Cast of Cinderella Story? A.fairy B.price C.Cinderella D.stepmother Answer: CDocument5 pagesWho Are The Main Cast of Cinderella Story? A.fairy B.price C.Cinderella D.stepmother Answer: CPasya RavilinaNo ratings yet

- Social Impact of Technology Online Exam 2Document13 pagesSocial Impact of Technology Online Exam 2Venisha Daniels0% (1)

- 2 - ADMM - Singapore, 19 October 2018 - (Final) AMRG On HADR - TOR For The Military Representative To The AHA CentreDocument10 pages2 - ADMM - Singapore, 19 October 2018 - (Final) AMRG On HADR - TOR For The Military Representative To The AHA CentresohbanaNo ratings yet

- Fispq Alcool 46,2°Document10 pagesFispq Alcool 46,2°Jeferson LeandroNo ratings yet

- Azp S 60Document8 pagesAzp S 60hartmann10No ratings yet

- Catching Spies - Principles and Practices of Counterespionage - Paladin PressDocument204 pagesCatching Spies - Principles and Practices of Counterespionage - Paladin PressMarkk211100% (8)

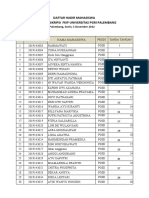

- Daftar Nama Mahasiswa Pelatihan SkirpsiDocument24 pagesDaftar Nama Mahasiswa Pelatihan SkirpsiRanti Ponika SariNo ratings yet

- Chapter18 Disappointmentsinmadrid Rizalslifeworksandwritingsofageniuswriterscientistandanationalhero 130217024624 Phpapp01Document22 pagesChapter18 Disappointmentsinmadrid Rizalslifeworksandwritingsofageniuswriterscientistandanationalhero 130217024624 Phpapp01Juan TamadNo ratings yet

- Hitman ContractDocument31 pagesHitman Contractmedithe13thNo ratings yet

- Paciano The Hero's HeroDocument11 pagesPaciano The Hero's HeroLovely Platon CantosNo ratings yet

- 10aug News NetVersDocument28 pages10aug News NetVersKen WhyteNo ratings yet

- Unexplained Mysteries - Mona Lisa's Eyes Reveal CodeDocument33 pagesUnexplained Mysteries - Mona Lisa's Eyes Reveal CodeFirst LastNo ratings yet