Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Self-Reflection Exercises Influence User Comprehension: A Usability Study Report

Uploaded by

Michael HalloranOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Self-Reflection Exercises Influence User Comprehension: A Usability Study Report

Uploaded by

Michael HalloranCopyright:

Available Formats

SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES, LITERATURE, CULTURE AND COMMUNICATION

ASSIGNMENT SUBMISSION FORM

Student Name: Student ID Number: Course of Study: Year: Lecturer Name: Module Code: Date of Submission: Michael Halloran 13035657 Technical Writing (Distance Learning) Graduate Certificate 2013 Yvonne Cleary TW5221 29 November 2013

I, Michael Halloran, declare that the attached essay/project is entirely my own work, in my own words, and that all sources used in researching it are fully acknowledged and all quotations properly identified

How Self-Reflection Exercises Influence User Comprehension: A Usability Study Report

Michael Halloran Student Number: 13035657

Course Name: Graduate Certificate in Technical Communication Module Code: TW5221 Supervisor: Dr. Yvonne Cleary, University of Limerick Date of Submission: 29 / 11/ 2013

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Abstract

This research report details a usability study of an online grammar course for teachers of English as a foreign language. The purpose of the study was to investigate if participants understanding of course concepts improved after completing self-reflection exercises. Ten teachers divided into two teams acted as test participants. All participants did the first unit of the course. However, the test intervention required one team to complete all embedded self-reflection exercises while the other team ignored them. Afterwards, the researcher tested each participant on grammar concepts in a post-course exam of ten questions. The researcher used these exam results to carry out a t-test of two independent means in order to evaluate the test hypothesis. This report includes an extensive literature review, a methodology section, a discussion section, and three appendices. KEY WORDS: Constructivism, e-learning, hypothesis test, online course, self-reflection, usability test.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Prof. Philip Rubens for helping me to refine this research project. I also want to thank Dr. Yvonne Cleary for her advice, encouragement, and mentorship over the course of TW5221. I want to thank the participants for setting aside time to take part in the test. Finally, I want to thank Liam Halloran and Bryna Greenlaw for proofreading the final report.

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Contents

Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... i Section 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 Section 2: Literature review ....................................................................................................... 2 Section 2.1: Overview ........................................................................................................... 2 Section 2.2: Theories of education and e-learning: behaviourism, cognitivism, constructivism and connectivism ........................................................................................... 2 Section 2.3: Usability, user experience and e-learning .......................................................... 5 Section 2.4: Data analysis of usability tests (hypothesis testing) .......................................... 8 Section 2.5: Conclusion ......................................................................................................... 8 Section 3: Methodology ............................................................................................................. 9 Section 3.1: Hypothesis ......................................................................................................... 9 Section 3.2: Quantitative usability testing an empirical research method .......................... 9 Section 3.2.1: Sample selection: choosing participants ..................................................... 9 Section 3.2.2: Control conditions..................................................................................... 10 Section 3.2.3: Ethical considerations ............................................................................... 10 Section 3.2.4: Procedure ................................................................................................. 10 Section 3.2.5: Statistical data analysis ............................................................................. 11 Section 4: Results and discussion ............................................................................................ 12 Section 4.1: Testing the difference between two means ...................................................... 12 Section 4.2: Discussion of research questions ..................................................................... 13 Section 4.3: Possible reasons for test results ....................................................................... 13 Section 4.4: Conclusion and recommendations ................................................................... 14 Section 5: References ............................................................................................................... 15 Appendix 1: Exam sheet .......................................................................................................... 18 Appendix 2: Instruction sheet .................................................................................................. 19 ii

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Appendix 3: Research ethics committee consent form ............................................................ 20

List of Figures

Figure 1. The User Experience Honeycomb (Morville 2004)................................................ 5 Figure 2. Post-course exam results. ......................................................................................... 12

iii

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 1: Introduction

This is a report on a usability study of e-learning interfaces and whether self-reflection exercises should be included in online courses. The usability study was quantitative in that it gathered numeric data from user testing. The purpose of the usability study was to test the impact of embedded self-reflection exercises on users of online courses and whether self-reflection is useful in helping users understand concepts they come across. The course that I tested was Grammar for Teachers: Language Awareness. Teachers at the university where I work did the course as part of their professional development. However, I tended to ignore the self-reflection exercises when I did the course myself and I wanted to know why. Through this study, I wanted to find out why the designer included the self-reflection exercises in the course, whether the exercises were really necessary, and whether they raised or lowered student attrition rates. However, these questions proved to be subjective and not easily tested. Therefore, Professor Philip Rubens helped me refine my ideas into a quantitative study based on a post-course exam of ten questions (see Appendix 1). This report details the background, the methodology of data collection, the control conditions, the ethical considerations, the results of the study, and a discussion of the data. Ten participants volunteered to do the first unit of the course as well as the exam. The number of participants, the scope and the length of the study were limited by time, location, and resources. The layout of this report is as follows: Section 2 is a review of literature dealing with learning theory, usability testing and hypothesis testing. Section 3 deals with the test hypothesis and the methodology used to carry out the usability study. Finally, Section 4 presents the results of the study and offers some recommendations.

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 2: Literature review

This review looks at some of the literature that has been written on the theory and usability of e-learning programs. It also includes a short description of hypothesis testing as outlined by Hughes and Hayhoe (2008, pp.64-71).

Section 2.1: Overview

E-learning is becoming a major organizational use of the internet (Zaharias and Poylymenakou 2009, p.76; Angelino et al 2007, p.2). Blended learning, already ubiquitous in universities, is penetrating second-level education; e-learning programs are also being used for corporate and professional development programs. Koohang et al (2009, p.91) state that constructivist learning theory focuses on knowledge construction based on learners previous experience and is therefore a good fit for e-learning because it ensures learning among learners. Ally (2001, p.31) states that learners should be given time and the opportunity to reflect; embedded questions will encourage learners to reflect on and process information in a relevant and meaningful manner. Alley suggests getting students to generate a learning journal. Koohang et al (2009, p.95) agree by stating that reflection activities will encourage the learner to be responsible for his or her own learning. But what are the other theories behind e-learning?

Section 2.2: Theories of education and e-learning: behaviourism, cognitivism, constructivism and connectivism

Early online courses were designed based on behaviourism (Ally 2011, p.19). This school of thought focuses on learners observable and measurable behaviours (Ally 2011, p.19). A behaviourist online course would: Inform students of course outcomes so they can set expectations. Have regular tests as an imbedded part of course design. Introduce learning material in a sequenced way. Encourage students to provide feedback.

Cognitivism looks at learning from an information processing point of view (Ally 2011, p.20). A cognitivist online course would: Place important information in the centre of the screen for reading. 2

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Highlight critical information with headings and clear formatting. Tell learners why they should take the course. Match the difficulty level to the learners cognitive level.

Jakob Nielsen in an interview with elearningpost (Nichani 2001) touches on an aspect of cognitivism:

You need to keep all the content fresh in learners mind [ sic]For example, response time. Even after a few seconds you always forget what was the track or sequence you were followingIt is important that your brain keeps the context. (Nichani 2001 para. 4.)

Ally also says a cognitivist course would encourage students to use their existing knowledge to help them make sense of the new information (Ally 2011, p.24). Some other aspects of this approach include: Chunking information to make it more memorable (Miller 1956). Varied learning strategies to accommodate different kinds of learners. Varied modes of information delivery: textual, visual and verbal. Learner motivation strategies: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. Metacognition: make a student aware of their learning capabilities. Assignments that have real-life application and information.

As mentioned above, constructivism sees the learner as active. Stimuli are received from the outside but it is the learner who actively creates the knowledge (Ally 2011, p.30). A constructivist online course would: Give learners meaningful activities in practical situations. Provide first-hand information, without the contextual influence of an instructor, so that students can personalise the information themselves. Encourage cooperative learning. Provide guided discovery activities. Use embedded questions (or a learning journal) to encourage learner reflection. Provide a high-level of interactivity.

Finally, connectivism is a theory for the digital age, where individuals learn and work in a networked environment (Ally 2011, p.34). Ally sketches some general guidelines based on this theory. Learners need to: 3

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Be autonomous and independent; appropriate use of the internet is encouraged. Unlearn old information and models in favour of the most up-to-date information and models; learners need to identify the most important information. Be active in a network of learning and acquire knowledge on an ongoing basis. Must be allowed to connect with others around the world in order to share knowledge and opinions. Gather information from many resources to reflect the networked world and the diversity of thinking within it.

Ally states that further work needs to be done on how this theory can be used by educators to design learning materials (Ally 2011, p.38). Finally, Ally suggests these different theories can be used to deal with different aspects of a course: Behavourism to teach facts. Cognitivism to teach principles and processes. Constructivism to teach real-life applications of learning.

Anderson (2011) provides a framework of how people learn: Knowledge-centred learning give access to a vast selection of content and activities but quality information is highlighted and filtered by the community of users. Assessment-centred learning is based on formative and summative assessment by self, peer and teachers (Anderson 2011, p.66). Learner-centred learning changes in response to group and learner models and content is changed based on student and teacher use. Community-centred learning uses many formats for collaborative and individual interaction.

In relation to knowledge-based and community-centred learning, Nielsen discusses usability, design and aesthetics of good discussion forums for learners:

I actually believe much more in discussion groups than I believe in chat rooms as ways of allowing students to interactreal-time chat effectively becomes very thin and not nearly as valuable as discussion groups where people can think a little bit before they post and the instructor can moderate it which a also good. (Nichani 2001, para. 10)

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 2.3: Usability, user experience and e-learning

What is usability? Nielsen (2012, What Definition of Usability, para. 1) defines usability as a quality attribute that assesses how easy user interfaces are to use and defines it by five qualities: Learnability. Efficiency. Memorability. Errors (the quantity and quality of errors a user makes). Satisfaction. Utility (does the interface do what the user needs?).

User experience (UX) is related to usability in that it focuses on having a deep understanding of users, what they need, what they value, their abilities, and also their limitations (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services 2013a, para. 1). Morville (2004) uses a honeycomb to illustrate the facets of user experience:

Figure 1. The User Experience Honeycomb (Morville 2004).

The most basic way to improve usability is user-testing (Nielsen 2012, How to Improve Usability, para. 1) and this process is three-fold: Get representative users to test the interface. Ask users to do representative tasks. 5

TW5221 Observe users and take notes on their experience.

Michael Halloran - 13035657

The U.S Department of Health & Human Services (2013b) outlines some other evaluation methods: Focus groups: moderated discussion involving five to ten participants. Card sort testing: participants organise topics into categories that make sense to them. Wireframing: creating a two-dimensional illustration of a pages interface. First click testing: examines what a test participant would click on first on the interface in order to complete their intended task. Satisfaction surveys.

The U.S Department of Health & Human Services goes on to discuss what the researcher should do after gathering data from one of the above methods: Evaluate the usability of the website. Recommend improvements. Implement recommendations. Re-test the site to measure the effectiveness of your changes.

While these methods can help researchers test usability, there are recognised usability principles for interaction design, often referred to as heuristics (Nielsen 1995a). Heuristic evaluation is part of an iterative design process and usual involves a team of evaluators. Nielsen recommends the use of five evaluators, but three at the least (Nielsen 1995b, para. 2). Jefferies and Desurvire (1992, p.39) found that just one evaluator was the least powerful evaluating technique when they experimented with different usability tests. Heuristic evaluation does not provide a systematic way to generate fixes, but rather aims to solve design issues by reference to established usability principles (Nielsen 1995b, para. 12). Nielsen (1995a) provides a list of 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design: Visibility of system status. Match between system and the real world. User control and freedom. Consistency and standards. Error prevention. 6

TW5221 Recognition rather than recall. Flexibility and efficiency of use. Aesthetic and minimalist design. Help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors. Help and documentation.

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Do these principles apply to e-learning? A team at The University of Georgia found that Nielsens list needed to be augmented (Benson et al 2002). They evaluated an e-learning program designed for the American Red Cross. They created a protocol for e-learning heuristic evaluation and fifteen usability and instructional design heuristics for the evaluation of e-learning programs. Their augmented evaluation heuristics included Nielsens original ten and five new principles: Learning Design. Media Integration. Instructional Assessment. Resources. Feedback.

Zaharias and Poylymenakou (2009) suggest that a usability evaluation method for e-learning needs to place motivation above functionality. They split e-learning usability attributes in two: usability and instructional design. Under usability they include, navigation learnability, accessibility, consistency and visual design. Under instructional design they include, interactivity/engagement, content and resources, media use, learning strategies design, feedback, instructional assessment and learner guidance and support (Zaharias and Poylymenakou 2009, p.80). This ultimately feeds into the most important part of e-learning, motivation by students: attention, relevance, confidence and satisfaction. Intrinsic motivation can be characterised as the drive arising within the self to carry out an activity whose reward is derived from enjoyment of the activity itself (Zaharias and Poylymenakou 2009, p.80) The learning interface needs to encourage intrinsic learning motivation. Ally says that extrinsic motivation should also be used, citing Kellers ARCS model (Attention, Relevance Confidence and Satisfaction) (Keller 1987; Ally 2011, p.28).

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 2.4: Data analysis of usability tests (hypothesis testing)

To test and analyse a usability intervention (the independent variable), a researcher will use two groups: a test group and a control group (Hughes and Hayhoe 2008, p.64). The results of the test are known as the dependent variable. The research analyses the average results of the test group and control group to see if there is a statistically significant difference. Therefore, it is important to include these factors when stating a test hypothesis. In order to test the hypothesis Hughes and Hayhoe (2008, p.65; p.71) suggest using Microsoft Excel to conduct a t-test of two independent means: State the test hypothesis, including the independent variable, the dependent variable and the expected direction. Recast the test hypothesis as a null hypothesis. Collect the data through the researchers chosen method. Enter data into a spreadsheet. Use the function COUNT to tally the sample sizes of the test and control groups. Use the function AVERAGE to calculate the mean. Use the function STDEV to calculate the standard deviation for each group. Standard deviation is an indicator of the variation of the data in the sample[it] is helpful for envisioning how widely the data vary from the average (Hughes and Hayhoe 2008, p.63). Use the function TTEST to calculate the probability (the p value) that the results could be caused by differences in the samples, rather than the intervention. Hughes and Hayhoe (2008, p71) state that typically, you can reject the null if the p value is less than 0.1. Finally, if you can reject the null, then accept the test hypothesis.

Section 2.5: Conclusion

This literature review has looked at the theories behind e-learning course design and how to test the usability of such courses. Online courses will become more central to general education and connectivism, as mentioned by Ally (2011), might be a very large target for research and potential applications.

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 3: Methodology

Grammar for Teachers: Language Awareness is a course designed for future, inexperienced and experienced teachers of English as a foreign language. To successfully complete the course users must reflect upon [their] own knowledge of the English languageparticipate in discussion forums with other teacherskeep a learner journal (Cambridge University Press and UCLES 2013). All of these components suggest a strong constructivist basis for the course.

Section 3.1: Hypothesis

Does self-reflection actually help students process information and become better learners? I set about proving the following hypothesis: In online courses, users will better understand course concepts if they complete selfreflection exercises. The goal of testing this hypothesis was to establish whether designers should include selfreflection exercises in online courses. To reach this goal, I proposed these questions: Do users understand course concepts better after they self-reflect? Do users misinterpret course concepts if they do not self-reflect? Is there any noticeable difference between users who self-reflect and those who dont?

Section 3.2: Quantitative usability testing an empirical research method

In order to generate data suitable for a t-test of two independent means, I chose the following testing methodology.

Section 3.2.1: Sample selection: choosing participants

The course is aimed at teachers of any level of experience. I chose ten participants, male and female, between the ages of twenty-five and sixty-five. All participants were teachers at different stages in their careers; none had attempted the course before. Based on Nielsens (1995b, para. 2) recommendation of using five usability evaluators, I divided the participants randomly into two groups of five. I will refer to these two groups as Team A (the test group) and Team B (the control group).

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 3.2.2: Control conditions

The usability study took place in a large, air-conditioned and brightly-lit university classroom. I observed one participant at a time. I spaced out the participant slots over five days between 8.30am and 4.30pm depending on the participants availability. Cambridge English Teachers suggested completion time of the whole course was five hours which is too long for most people to put time aside to complete. Instead, I chose Unit 1: Nouns and pronouns to act as a representative example of the whole course. I found that registration, Unit 1 itself, and the post-course exam took forty-five minutes for me to complete. I took this timing into account when informing participants about the length of the test. Finally, I provided all participants with the following items: A pencil and eraser. A Lenovo G480 laptop with wireless mouse and internet access. A pre-course task sheet (see Appendix 2). A post-course exam sheet (see Appendix 1). A bottle of water.

Section 3.2.3: Ethical considerations

The FAHSS Ethics Committee at the University of Limerick approved this quantitative research project. The approval included conducting pre-/post-surveys as part of a usability study. I answered No to all questions on the approval form checklist. Participants signed a consent form (Appendix 3) but will remain anonymous. I did not make any audio or video recordings. The anonymous exam sheet is the only record.

Section 3.2.4: Procedure

Participants sat at a desk with the laptop. They signed the consent form and received the task sheet. After they complete the task sheet, I directed them to complete Unit 1 Nouns and Pronouns using the onscreen directions only. I emphasised that they must read everything and watch every video. However, I implemented the following intervention: Team A members must attempt all self-reflection exercises. Team B members must ignore all the self-reflection exercises.

I observed all participants to ensure they followed this intervention protocol. I prompted them when they strayed from the instructions or provided them with assistance when they asked. 10

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Registration and unit completion took forty to eighty minutes depending on the participant. After they complete the unit, I removed the laptop and task sheet and gave the participants a pencil, eraser and exam sheet. The exam consists of ten questions which tested participants comprehension of the course concepts. Participants had to attempt all questions. The exam took less than five minutes to complete per participant.

Section 3.2.5: Statistical data analysis

The exam sheet consisted of ten questions and was based on concepts covered in the course. The first five questions required one answer. The second five questions required three answers. This added up to a potential total score of 20 out of twenty 20. I pilot tested the exam sheet on two colleagues. This was to see whether the questions were readable and easy to understand. While these two colleagues did sign the consent form, I did not keep their results for the record as this was simply a proofreading exercise. After the ten participants of the actual test had finished, I tallied up their exam scores and followed Hughes and Hayhoes (2008, p.71) hypothesis testing method as I outlined in the literature review.

11

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 4: Results and discussion

Below are the results of the analysis. In section 4.2 I restate my initial goal questions and discuss the answers.

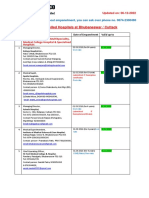

Section 4.1: Testing the difference between two means

Hypothesis: In online courses, users will better understand course concepts if they complete self-reflection exercises. Null Hypothesis: In online courses, users will better understand course concepts if they do not complete self-reflection exercises. When assigning arguments in the function TTEST (probability) in Microsoft Excel, I chose a one-tailed (directional) test. Under the type argument, I chose 3 as this was a nonpaired test where the variances were not equal (Hughes and Hayhoe 2008, p. 69). See Figure 2 below for details of the data analysis.

Post-Course Exam Results Team A Team B 8 18 17 12 15 14 16 14 11 15 n 5 5 mean 13.4 14.6 SD 3.78153 2.19089 p 0.28018

n= total sample size SD = standard deviation p= probability

Figure 2. Post-course exam results.

By reviewing the means of both groups we can see that the average score for Team A was 13.4 out of 20 while for Team B it was 14.6 out of 20. Already we see that the hypothesis is not accepted based on the raw averages. If the probability is less than 0.1 than the null hypothesis can be rejected. However, the p value is 0.28018, meaning the null hypothesis 12

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

cannot be rejected. Therefore, based on the available data: the test hypothesis is not accepted.

Section 4.2: Discussion of research questions

Based on the data, I will now answer my research questions as outlined in Section 3.1: Do users understand course concepts better after they self-reflect? No, Team A participants had a lower total average than Team B. Do users misinterpret course concepts if they do not self-reflect? No, Team B had a higher average than Team A and one Team B participant scored the highest of all the participants, 18 out of 20. Is there any noticeable difference between users who self-reflect and those who dont? No, there is only a 9% difference between the two groups averages.

Section 4.3: Possible reasons for test results

Does this all mean that self-reflection exercises are redundant and that we should accept the null hypothesis? Possibly. However, this would require us to reject a huge part of constructivist theory. Therefore, it is more likely that the test itself was flawed. There are several possible reasons why these results occurred: The sample size was not big enough. Unit 1 is an eighth of the total course. The test may not have been representative enough of the whole course. A test of two units may have been better. The exam sheet questions should be re-worded because two participants misunderstood questions 2 and 6. Unit 1 may not have been challenging enough. Nouns and pronouns are basic concepts for experienced teachers. Some participants may not have used the self-reflection exercises to their full potential. Some wrote very long passages while others wrote only a couple of lines. Participants may not have read the questions thoroughly. The participant who scored 18 out of 20 read every part of the online unit aloud. This participant also read the exam questions aloud twice. The exam questions may not have accurately reflected the self-reflection exercises.

13

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

In hindsight, the hypothesis is flawed. A better hypothesis might be worded to include the dependent variable; in this case, the results of the post-course exam: Users will have stronger recall of online course concepts in a post-task exam if they complete embedded self-reflection exercises.

Allowing participants to access the online journal of their self-reflections may have altered their test results. Allowing participants to discuss the reflections in the course forum could also have altered the results as well. The course self-reflection exercises may have been poorly designed themselves; they may have discouraged participants from really considering the course concepts.

Section 4.4: Conclusion and recommendations

In this report, I have presented a literature review of e-learning theory and usability, the methodology I used to test my hypothesis, and finally, an analysis of the resulting data. In Section 3.1, I stated that the goal of testing this hypothesis was to establish whether designers should include self-reflection exercises in online courses. Considering my test results, the answers to my research questions, as well as the possible faults with the test itself (as mentioned in Section 4.3), I have to state that the test results are inconclusive. It is possible that self-reflection exercises do not aid learners. However, self-reflection is an integral part of constructivist learning theory, and constructivism is central to contemporary e-learning design theory. Therefore, it is essential that further research is carried out in this area. I would recommend another study is carried out on Grammar for Teachers: Language Awareness, using a larger sample size and a larger representative section of the course. The future researcher should also take into account all the other faults I mentioned in Section 4.3 and address them before conducting the research.

14

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Section 5: References

Ally, M. (2011) Foundation of Educational Theory for Online Learning, in Anderson, T., ed., The Theory and Practice of Online Learning, 2nd ed., Edmonton: AU Press, 15-44. Anderson, T. (2011) Towards a Theory of Online Learning in Anderson, T., ed., The Theory and Practice of Online Learning, 2nd ed., Edmonton: AU Press, 45-74.

Benson, L., Elliott, D., Grant, M., Holschuh, D., Kim, B., Kim, H., Lauber, E., Loh, S. and Reeves, T.C. (2002) Usability and Instructional Design Heuristics for E-Learning Evaluation, in Barker, P. and Rebelsky, S., eds., Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2002, Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 1615-1621. Cambridge University Press and UCLES 2013 (2013) Grammar for Teachers: Language Awareness, Cambridge English Teacher available: http://www.cambridgeenglishteacher.org/courses/details/18606 [accessed 2 Nov 2013]. David, A. and Glore, P. (2010) The Impact of Design and Aesthetics on Usability, Credibility, and Learning in an Online Environment, Online Journal of Distance Learning [online], 13(4), available: http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/winter134/david_glore134.html [accessed 13 Oct 2013].

Hughes, M. and Hayhoe, G. (2007) A Research Primer for Technical Communication: Methods, Exemplars, and Analyses, New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Jeffries, R. and Desurvire, H. (1992) Usability testing vs. heuristic evaluation: was there a contest?, SIGCHI Bulletin, 24 (4), 39-41. Keller, J. (1987) Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design in Journal of Instructional Development, 10(3), 2-10.

15

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Koohang, A., Riley, L. and Smith, T. (2009) E-learning and Constructivism: From Theory to Application in Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects [online], 5, 91109, available: http://ijklo.org/Volume5/IJELLOv5p091-109Koohang655.pdf [accessed 2 Nov 2013]. Miller, G.A. (1956) The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limitations on our capacity for processing information in Psychological Review, 63, 81-97. Morville, P. (2004) User Experience Design, Semantic Studios [online], 21 June, available: http://semanticstudios.com/publications/semantics/000029.php [accessed 24 Nov 2013]. Nielsen, J. (1995a) 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design, Nielsen Norman Group [online], 1 January, available: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usabilityheuristics/ [accessed 13 Oct 2013]. Nielsen, J. (1995b) How to Conduct a Heuristic Evaluation, Nielsen Norman Group [online], 1 January, available: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-to-conduct-a-heuristicevaluation/ [accessed 13 Oct 2013]. Nielsen, J. (2001) First Rule of Usability? Don't Listen to Users, Nielsen Norman Group [online], 5 Aug, available: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/first-rule-of-usability-dontlisten-to-users/ [accessed 13 Oct 2013]. Nielsen, J. (2012) Usability 101: Introduction to Usability, Nielsen Norman Group [online] 4 January, available: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-tousability/ [accessed 13 Oct 2013]. Nichani, M., ed. (2001) Jakob Nielsen on e-learning, elearningpost [online], 16 January, available: http://www.elearningpost.com/articles/archives/jakob_nielsen_on_e_learning/ [accessed 13 Oct 2013].

16

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2013b) Usability Evaluation Basics Usability.gov [online], available at: http://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/usabilityevaluation.html [24 Nov 2013]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2013a) User Experience Basics, Usability.gov [online], available: http://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/userexperience.html [accessed 23 Nov 2013]. Zaharias, P. and Poylymenakou, A. (2009) Developing a Usability Evaluation Method for eLearning Applications: Beyond Functional Usability, International Journal of HumanComputer Interaction, 25(1), 75-98.

17

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Appendix 1: Exam sheet

EXAM SHEET Questions 1-5 are worth one point each

1. What is an alternative name for word class? 2. Give one example of an abstract, countable, common noun ______________________________________ ______________________________________

3. Complete the sentence:

____________________is a word that is used to show a sudden expression of emotion.

4. Complete the sentence:

____________________is a word that connects words, phrases and clauses in a sentence.

5. Complete the sentence:

Concrete nouns can be seen, touched or ____________________.

Questions 6-10 are worth three points each

6. Give three examples of determiners 1. 2. 3.

7. Give three examples of demonstrative pronouns 1. 2. 3.

8. Give three examples of ordinal number quantifiers 1. 2. 3.

9. Give three examples of collective nouns 1. 2. 3.

10. Give three examples of indefinite pronouns 1. 2. 3.

Total Score:

/20

18

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Appendix 2: Instruction sheet Instructions

1. Open Google Chrome. 2. In the search bar type www.cambridgeenglishteacher.org and press return. 3. In the top-right corner click register. 4. Fill in the registration form with your details (N.B. only use numbers and/or letters in your password). 5. Click create account. 6. Open your email inbox and select the message titled validate email address. 7. Follow the link in the message. 8. Sign into your new account. 9. Click courses in the navigation bar. 10. Scroll down to Grammar for Teachers: Language Awareness and click open. 11. Select Unit 1 Nouns and Pronouns and begin the course.

19

TW5221

Michael Halloran - 13035657

Appendix 3: Research ethics committee consent form

FACULTY OF ARTS, HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES RESEARCH ETHICS COMMITTEE CONSENT FORM

Consent Section: I, the undersigned, declare that I am willing to take part in research for the project entitled TW5221 Usability Study. I declare that I have been fully briefed on the nature of this study and my role in it and have been given the opportunity to ask questions before agreeing to participate. The nature of my participation has been explained to me and I have full knowledge of how the information collected will be used. I am also aware that my participation in this study may be audio recorded and I agree to this. However, should I feel uncomfortable at any time I can request that the recording equipment be switched off. I am entitled to copies of all recordings made and am fully informed as to what will happen to these recordings once the study is completed. I fully understand that there is no obligation on me to participate in this study. I fully understand that I am free to withdraw my participation at any time without having to explain or give a reason. I am also entitled to full confidentiality in terms of my participation and personal details.

______________________________________ Signature of participant

__________________________ Date

20

You might also like

- Enhancing Learning and Teaching Through Student Feedback in Social SciencesFrom EverandEnhancing Learning and Teaching Through Student Feedback in Social SciencesNo ratings yet

- 2 SCL Research in EnglishDocument199 pages2 SCL Research in EnglishDulio CalaveteNo ratings yet

- Teaching to Individual Differences in Science and Engineering Librarianship: Adapting Library Instruction to Learning Styles and Personality CharacteristicsFrom EverandTeaching to Individual Differences in Science and Engineering Librarianship: Adapting Library Instruction to Learning Styles and Personality CharacteristicsNo ratings yet

- LDP 603 Reserach MethodsDocument241 pagesLDP 603 Reserach MethodsAludahNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 FinalDocument13 pagesAssignment 1 Finalaljr_2801No ratings yet

- AC6630 C30 HandbookDocument44 pagesAC6630 C30 Handbooknurhanim ckNo ratings yet

- First and Second Year Course Booklet 17 18Document35 pagesFirst and Second Year Course Booklet 17 18Hay CiwiwNo ratings yet

- Intervnetion StrategyDocument165 pagesIntervnetion StrategyMuneeb KhanNo ratings yet

- Project Thesis Arham Learning TechniquesDocument33 pagesProject Thesis Arham Learning TechniquesMmaNo ratings yet

- A Holistic English Mid Semester Assessment For Junior High SchoolsDocument19 pagesA Holistic English Mid Semester Assessment For Junior High SchoolsIka Fathin Resti MartantiNo ratings yet

- Organizing Instruction and Study To Improve Student Learning IES Practice GuideDocument63 pagesOrganizing Instruction and Study To Improve Student Learning IES Practice GuidehoorieNo ratings yet

- Local Media8865838383823137779Document7 pagesLocal Media8865838383823137779Sharra DayritNo ratings yet

- PSY5332 Course Manual 2023Document7 pagesPSY5332 Course Manual 2023Adria CioablaNo ratings yet

- CT4 Module 5Document18 pagesCT4 Module 5DubuNo ratings yet

- Instructor GuidelinesDocument26 pagesInstructor Guidelinesgs123@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- ECON3124 Behavioural Economics S12013 PartADocument7 pagesECON3124 Behavioural Economics S12013 PartAsyamilNo ratings yet

- Conducting - Action ResearchDocument8 pagesConducting - Action ResearchCossette Rilloraza-MercadoNo ratings yet

- ESTALLDocument30 pagesESTALLSara Victoria ZAPATANo ratings yet

- A-6 Ismah Yusuf TanjungDocument11 pagesA-6 Ismah Yusuf Tanjungismah yusufNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Qualitative Research MethodsDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Qualitative Research MethodsBast JordNo ratings yet

- Pbis 4401Document2 pagesPbis 4401Putra FendiNo ratings yet

- Q1: What Are The Types of Assessment? Differentiate Assessment For Training of Learning and As Learning?Document14 pagesQ1: What Are The Types of Assessment? Differentiate Assessment For Training of Learning and As Learning?eng.agkhanNo ratings yet

- Scientific Thinking of The Learners Learning With The Knowledge Construction Model Enhancing Scientific ThinkingDocument5 pagesScientific Thinking of The Learners Learning With The Knowledge Construction Model Enhancing Scientific ThinkingKarlina RahmiNo ratings yet

- Course Outline VISN2211 2016Document20 pagesCourse Outline VISN2211 2016timeflies23No ratings yet

- Teaching Dossier: Andrew W. H. HouseDocument9 pagesTeaching Dossier: Andrew W. H. HouseMohammad Umar RehmanNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning MiniCourse 3Document4 pagesBlended Learning MiniCourse 3Tamir SassonNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Elearning in A Changing Landscape: A Scoping Study (Selscope)Document49 pagesSustainable Elearning in A Changing Landscape: A Scoping Study (Selscope)SravyaSreeNo ratings yet

- Action Reseacrh FinalDocument29 pagesAction Reseacrh FinalGlizen RamNo ratings yet

- Action Reseach PartsDocument7 pagesAction Reseach PartsVic BelNo ratings yet

- LDP 603 Reserach Methods Study Unit, MaDocument220 pagesLDP 603 Reserach Methods Study Unit, Mamoses ndambukiNo ratings yet

- Actiom - Research 23Document17 pagesActiom - Research 23MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Matt Oâ Leary - Classroom Observation - A Guide To The Effective Observation of Teaching and Learning-Routledge - 1 Edition (October 8, 2013) (2013)Document19 pagesMatt Oâ Leary - Classroom Observation - A Guide To The Effective Observation of Teaching and Learning-Routledge - 1 Edition (October 8, 2013) (2013)Mueble SkellingtonNo ratings yet

- An Evaluation of The Textbook English 6Document304 pagesAn Evaluation of The Textbook English 60787095494No ratings yet

- Critical Thinking and Reflective Practices Shazia BibiDocument6 pagesCritical Thinking and Reflective Practices Shazia Bibijabeen sadiaNo ratings yet

- PUBLG114 Global Governance Syllabus 2014 PDFDocument26 pagesPUBLG114 Global Governance Syllabus 2014 PDFAnnie FariasNo ratings yet

- Indicators Are Key in Learning ArgumentDocument12 pagesIndicators Are Key in Learning Argumenthnif2009No ratings yet

- JLS 714Document284 pagesJLS 714Mia SamNo ratings yet

- Course Manual OB 2021-2022Document13 pagesCourse Manual OB 2021-2022Gloria NüsseNo ratings yet

- Ismah Yusuf Tanjung - CBR - Research and DevelopmentDocument12 pagesIsmah Yusuf Tanjung - CBR - Research and Developmentismah yusufNo ratings yet

- Student CenteredDocument27 pagesStudent CenteredBezabih AbebeNo ratings yet

- Towards Productive Reflective Practice in MicroteachingDocument25 pagesTowards Productive Reflective Practice in MicroteachingEzzah SyahirahNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Template: 1 Summary InformationDocument9 pagesLesson Plan Template: 1 Summary InformationCruz ItaNo ratings yet

- Episode 7Document14 pagesEpisode 7Joselito CepadaNo ratings yet

- TonNuHoangAnh LAN6271 TeachingESLLearners Assignment1Document47 pagesTonNuHoangAnh LAN6271 TeachingESLLearners Assignment1Anh TonNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document4 pagesModule 4Sean Darrell TungcolNo ratings yet

- Pos 350, Spring 2021 SavesDocument8 pagesPos 350, Spring 2021 SavesZo. KozartNo ratings yet

- Assingment - 2Document12 pagesAssingment - 2project manajement2013No ratings yet

- FLTM Unit 1 Lesson 3 UpdatedDocument19 pagesFLTM Unit 1 Lesson 3 UpdatedДарья ОбуховскаяNo ratings yet

- Research (Burns) - Preliminary GuideDocument5 pagesResearch (Burns) - Preliminary GuideRoberto De LuciaNo ratings yet

- Research Methods For Primary EducationDocument82 pagesResearch Methods For Primary EducationZan Retsiger100% (1)

- Creating Ethical ResearchDocument108 pagesCreating Ethical ResearchAlexandra StanNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking - Syllabus - New - Template Based On Prof Ku Materials2Document6 pagesCritical Thinking - Syllabus - New - Template Based On Prof Ku Materials2Don Kimi KapoueriNo ratings yet

- Blair Mod 2 Research Teacher ResourcesDocument58 pagesBlair Mod 2 Research Teacher ResourcesJanie VandeBergNo ratings yet

- Example 2 RM2Document31 pagesExample 2 RM2HananNo ratings yet

- Draft Proposal AzizahDocument9 pagesDraft Proposal AzizahAmi AsnainiNo ratings yet

- FloridathesisDocument28 pagesFloridathesisrichardbarcinilla02No ratings yet

- Numerology Numeric CodeDocument13 pagesNumerology Numeric Codedeep mitraNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Scientific Research Methodology: Ha Noi Open University Faculty of EnglishDocument30 pagesAssignment On Scientific Research Methodology: Ha Noi Open University Faculty of EnglishNguyễn Thị Trường GiangNo ratings yet

- Developing Critical Skills Through The Use of ProbDocument12 pagesDeveloping Critical Skills Through The Use of ProbEugenio MartinezNo ratings yet

- D Kennedy Learning OutcomesDocument71 pagesD Kennedy Learning OutcomesRanganathan Nagendran100% (1)

- Sanskrit Lessons: �丘��恆� � by Bhikshuni Heng HsienDocument4 pagesSanskrit Lessons: �丘��恆� � by Bhikshuni Heng HsiendysphunctionalNo ratings yet

- Stochastic ProcessesDocument264 pagesStochastic Processesmanosmill100% (1)

- Corporate Restructuring Short NotesDocument31 pagesCorporate Restructuring Short NotesSatwik Jain57% (7)

- Advantages Renewable Energy Resources Environmental Sciences EssayDocument3 pagesAdvantages Renewable Energy Resources Environmental Sciences EssayCemerlang StudiNo ratings yet

- Percentage and Profit & Loss: Aptitude AdvancedDocument8 pagesPercentage and Profit & Loss: Aptitude AdvancedshreyaNo ratings yet

- VLT 6000 HVAC Introduction To HVAC: MG.60.C7.02 - VLT Is A Registered Danfoss TrademarkDocument27 pagesVLT 6000 HVAC Introduction To HVAC: MG.60.C7.02 - VLT Is A Registered Danfoss TrademarkSamir SabicNo ratings yet

- Advanced Java SlidesDocument134 pagesAdvanced Java SlidesDeepa SubramanyamNo ratings yet

- T688 Series Instructions ManualDocument14 pagesT688 Series Instructions ManualKittiwat WongsuwanNo ratings yet

- English For General SciencesDocument47 pagesEnglish For General Sciencesfauzan ramadhanNo ratings yet

- Risha Hannah I. NazarethDocument4 pagesRisha Hannah I. NazarethAlpaccino IslesNo ratings yet

- Aspek Perpajakan Dalam Transfer Pricing: Related PapersDocument15 pagesAspek Perpajakan Dalam Transfer Pricing: Related PapersHasrawati AzisNo ratings yet

- Abbas Ali Mandviwala 200640147: Ba1530: Information Systems and Organization StudiesDocument11 pagesAbbas Ali Mandviwala 200640147: Ba1530: Information Systems and Organization Studiesshayan sohailNo ratings yet

- Empanelled Hospitals List Updated - 06-12-2022 - 1670482933145Document19 pagesEmpanelled Hospitals List Updated - 06-12-2022 - 1670482933145mechmaster4uNo ratings yet

- Lotus Exige Technical InformationDocument2 pagesLotus Exige Technical InformationDave LeyNo ratings yet

- How To Be A Better StudentDocument2 pagesHow To Be A Better Studentct fatima100% (1)

- Dash 3000/4000 Patient Monitor: Service ManualDocument292 pagesDash 3000/4000 Patient Monitor: Service ManualYair CarreraNo ratings yet

- Functions PW DPPDocument4 pagesFunctions PW DPPDebmalyaNo ratings yet

- LSL Education Center Final Exam 30 Minutes Full Name - Phone NumberDocument2 pagesLSL Education Center Final Exam 30 Minutes Full Name - Phone NumberDilzoda Boytumanova.No ratings yet

- Garments Costing Sheet of LADIES Skinny DenimsDocument1 pageGarments Costing Sheet of LADIES Skinny DenimsDebopriya SahaNo ratings yet

- Coco Mavdi Esl5Document6 pagesCoco Mavdi Esl5gaurav222980No ratings yet

- Annex To ED Decision 2013-015-RDocument18 pagesAnnex To ED Decision 2013-015-RBurse LeeNo ratings yet

- Furnace Temperature & PCE ConesDocument3 pagesFurnace Temperature & PCE ConesAbdullrahman Alzahrani100% (1)

- Ward 7Document14 pagesWard 7Financial NeedsNo ratings yet

- What Is Product Management?Document37 pagesWhat Is Product Management?Jeffrey De VeraNo ratings yet

- Current Surgical Therapy 13th EditionDocument61 pagesCurrent Surgical Therapy 13th Editiongreg.vasquez490100% (41)

- Book Speos 2023 R2 Users GuideDocument843 pagesBook Speos 2023 R2 Users GuideCarlos RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Economizer DesignDocument2 pagesEconomizer Designandremalta09100% (4)

- Flowrox Valve Solutions Catalogue E-VersionDocument16 pagesFlowrox Valve Solutions Catalogue E-Versionjavier alvarezNo ratings yet

- ASHRAE Elearning Course List - Order FormDocument4 pagesASHRAE Elearning Course List - Order Formsaquib715No ratings yet

- Angelo (Patrick) Complaint PDFDocument2 pagesAngelo (Patrick) Complaint PDFPatLohmannNo ratings yet