Professional Documents

Culture Documents

North African Oil & Gas 201401

Uploaded by

gweberpe@gmailcom0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views9 pagesNorth African O&G industry forecast

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNorth African O&G industry forecast

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views9 pagesNorth African Oil & Gas 201401

Uploaded by

gweberpe@gmailcomNorth African O&G industry forecast

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Table 1.

North Africa key statistics

I

Algeria Egypt Libya Morocco Tunisia

Population (million) 2013 est. 38.1

Population growth rate 1.9%

Life expectancy, years 76.18

Age structure:

o -14 years 28.1%

15 - 24 years 18.1%

25 - 54 years 42.7%

55 - 64 years 6.0%

65 + years 5.1%

Government type Republic

Area (million km

2

) 2.38

Population density 15.99

Arable land, % 3%

Literacy, % 72.6%

Male literacy 81.3%

Female literacy 63.9%

GDP, billion US$, 2010 est. 251

GDP growth rate, 2010 est. 3.3%

GDP / capita 2010 est. 7300

GDP, billion US$, 2012 est. 277

GDP growth rate, 2012 est. 2.5%

GDP /capita 2012 est. 7600

GDP composition 2012 est.

Agriculture 8.9%

Industry 60.9%

Services 30.2%

Unemployment, youth 15 - 24 21.5%

Total unemployment, 2012 est. 10.2%

Population below poverty line 23.0%

GDP / capita 2010 7300

GDP / capita 2012 7600

Youth employment 21.5%

Total unemployment 10.2%

North Africa overview and the

'Arab Spring'

85.3

1.88%

73.19

32.3%

18.0%

38.3%

6.6%

4.8%

Republic

1.00 .

85.68

3%

73.9%

81.7%

65.8%

498

5.1%

6200

549

2.2%

6700

14.7%

17.0%

51.0%

24.8%

13.5%

20.0%

6200

6700

24.8%

13.5%

North Africa is viewed as having been the launching pad for the

protests and demonstrations that later became known as the

'Arab Spring' . This ic; a complex and evolving process across the

region, but at the most basic level, the protestors expressed

dissatisfaction with government and the authorities. The

people held that legitimate governments should be elected by

the people. There were many root causes of the protests,

including poverty, unemployment, a widening gap between

rich and poor, violation of human rights, and a desire to move

December 2013 HYDROCARBON ___ _ _ _ ___ ENGINEERING

6.0 32.6 10.8

4.85% 1.04% 0.95%

75.83 76.31 75.46

27.3% 27.1% 23.0%

18.6% 18.0% 16.5%

45.6% 41.7% 44.7%

4.6% 7.0% 8.1%

3.9% 6.3% 7.7%

Republic Monarchy Republic

1.76 0.45 0.16

3.41 73.15 69.75

1% 19% 17%

89.5% 67.1% 79.10%

95.8% 76.1% 87.40%

83.3% 57.6% 71.1%

91 151 100

4.2% 3.2% 3.7%

14000 4800 9400

79 174 107

104.5% 3.0% 3.6%

12300 5400 9900

1.6% 15.1% 8.9%

43.5% 31.7% 31.9%

54.9% 53.2% 49.8%

17.9% 30.7%

30.0% 9.0% 17.4%

33.0% 15.0% 3.8%

14000 4800 9400

12300 5400 9900

17.9% 30.7%

30.0% 9.0% 17.45

towards democratic reforms and greater freedom from too

powerful, and often corrupt, governments. There were a

variety of responses from entrenched interests, all too many of

which escalated into violence and outright civil war. The Arab

Spring protests quickly toppled the long standing dictatorships

of u n i ~ i a Egypt, and Libya. The civil war in Libya ended only

when Muammar Qaddafi was slain. King Mohammed VI of

Morocco, the lone monarch remaining, appeared to be more in

touch with the populace, allowing peaceful protests and

qUickly promising a new constitution. This staved off any

serious violence. .

,

I

0.35 .-----------------------,

0.3

0.3 r---------------------'

0.248

0.2S r-------'-'-'--'o------

O. IS I

0.1

0.21S

0.102

AI geriiJ Egypt Libya

0.179

Morocco

0.307

0.174

Tunisia

Figure 1. High rates of unemployment and youth

unemployment.

,...--------------------- -,

- Algeri a

- Egypt

- libya

- Morocco

- Tunisi&!

- - Unit ed Kinadom

,..- --_.-. .......

1.S

0.5 r---..:;;:::::::-- ---:;r-- ------.:-:;;;;;o---..... ==;;;--j

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012

Figure 2. North African gasoline prices relative to

UK prices.

Two years later, much of North Africa remains in a state of flux.

As new leaders have emerged, they have found leadership to be a

challenge. Gaining the consensus needed to implement reforms

has been time consuming. Unfortunately, the delays cause

frustration, which in turn makes consensus more difficult to reach.

Some observers have even lamented that the Arab Spring has

turned into the 'Islamist Winter', not just in North Africa but also in

the Middle East, where violence in Syria has reached crisis

proportions.

Table 1 provides an overview of key statistics in Algeria, Egypt,

Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia. Only 1- 3% of the land in Algeria,

Egypt, and Libya is arable. Most of the population lives on the

coast. The smaller, coastally oriented countries of Tunisia and

Morocco have 17% and 19% arable land. The Sahara Desert

continues to expand. Desertification is a major problem, impeding

agricultural activity in much of the inland area. Moreover, the

residents of the inland desert areas often have little to do with

their more urbanised coastal counterparts, and they may largely be

excluded from participation in the new governments. This also

contributes to internal strife.

North Africa's most populous country is Egypt, with

85.3 million people, accounting for nearly half of the region's

population. Algeria's population is 38.1 mj llion, followed by

Morocco with 32.6 million people, Tunisia with 10.8 million, and

Libya with 6 million. Libya is the only country that had a recent

drop in population, related to the civil war. The age structure is

young, with only approximately 4 - 7% of the North African

population aged 65 years and older. Literacy rates are below the

world average, with a wide disparity between male literacy rates

and female literacy rates.

December 2013

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

Figure 1 displays the high rates of unemployment and youth

(ages 15 - 24) unemployment in the North African countries, as

estimated by the CIA World Factbook. The data are 2012 estimates,

with the exception of Libya, for which no youth unemployment

rates are available, and the overall unemployment rate of 30% is an

estimate for 2004. Unemployment is viewed as an increasingly

critical social problem. Tunisia's rebellion in January 2011 was in fact

attributed largely to unemployment and frustration among young

people. Total unemployment is estimated at 17.4%, and it is an

extremely high 30.7% for young people aged 15 - 24, including many

who have college degrees. Tunisia's government had been led for

23 years by President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali , who had pledged

many improvements in prosperity, education, health care, and

social stability. But the realities continually fell short of the

promises. By the end of 2010, a college educated 26 year old

named Muhammad Bouazizi protested in a self immolation that set

off such a rebellion that President Ben Ali had to leave the country.

The Tunisian rebellion is regarded as a starting point for the

rebellions that spread in Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Algeria.

The 2011 Egyptian Revolution began with a popular uprising on

January 25

th

, and the revolution is ongoing. On February 11th, after

weeks of protests and demonstrations, Egyptian President Hosni

Mubarak resigned from office. Egyptians were unhappy with many

of the same social issues seen in Tuni sia: high unemployment, low

wages, inflation, police brutality, and political censorship. These

same problems plagued other North African countries. There was a

wave of protests, including self immolations, in Algeria, where the

protests grew stronger after the Egyptian Revolution removed

President Mubarek. The successor, President Muhammad Morsi,

was elected in 2012, but he too was ousted in 2013, and the country

remains in flux.

The civil war in Libya escalated rapidly. A series of peaceful

protests in early 2011 were countered with crushing force by

Colonel Qaddafi's troops. The protests escalated into a widespread

uprising, and the rebel forces set up a rival seat of government in

Benghazi, naming themselves the National Transitional Council. The

rebels were backed by NATO, and the civil war ended only when

Colonel Qaddafi was slain in October 2011. Yet the provisional

government has struggled ever since to forge unity among the

disparate tribes, regions and parties that make up the country.

Security has not been restored, and armed militias remain active. In

September 2012, the US Embassy in Benghazi was attacked by

heavily armed militants, and the US Ambassador,). Christopher

Stevens, was assassinated. At the time of this writing, a year has

passed, and although arrests have been made, the investigation has

not been concluded. Important oil export infrastructure has been

blockaded, cutting into vital oil export revenues. The Libyan

government received 91% of its revenues from the oil and gas

industry in 2011, underscoring the critical need for a healthy

flow of oil :

North Africa's oil and natural gas

resources and production

Key role of oil and gas revenues

The social and political turmoil in North Africa has hampered

developments in the oil and gas industry. Because oil and gas

contribute so much to the local economies, this is having a cyclical

impact on the ability of governments to meet the expectations of

the citizenry. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, oil and

,

,

I

- Egypt, Arab Rep.

- Libya

- Morocco

- Tunisia

- - United Kingdom

;;

;r

;;

.... ---."

1.5

;;;;

------;

0.5

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010

Figure 3. North African pump prices for diesel

relative to UK prices.

Figure 4. North Africa proved oil reserves,

billion bbls.

51 2300

Figure 5. North Africa proved gas reserves,

billion ft3.

Al geria

EllYpt

UbY'

gas

0.06 ,..--------------------------.

b

; om '- ' ------- ---------------,

....... N. Africa % of World Gas Reserves

___ N. Africa % of World Oil Reserves

1'"1

: 0.Q1

1

'-----------------------

o -

Figure 6. North Africa: Falling share of global oil

and gas reserves.

December 2013 HYDROCARBON _ _ ___ _____ ENGINEERING

revenues in 2011 accounted for 10% of government revenue in

Egypt, 67% of government revenues in Algeria, and a whopping 91%

of government revenues in Libya. For the governments now in

transition in North Africa, reviving and stimulating the hydrocarbon

industry is critical.

Pricing issues

It is typical for oil and gas rich countries to use the revenues from

the hydrocarbon sector to subsidise other sectors and programs. It

is also common for governments to subsidise fuel prices. This is

viewed as a way of sharing the wealth with the citizens. But it also

creates its own set of market problems. For example, demand for

the subsidised fuel or fuels may grow so disproportionately that

the pattern of fuel demand is skewed and encourages inefficient

energy use. The domestic refining industry may not be able to

satisfy the lopsided pattern of demand, and subsidised fuel prices

may discourage the investment needed to change this. Subsidised

fuels may also be smuggled out of the country, giving rise to

organised crime. Eventually, the government bill for fuel subsidies

may outweigh the benefits, yet removing long standing subsidies

may be tantamount to political suicide.

All of the North African governments subsidise gasoline and

diesel prices. Figure 2 compares the pump price of gasoline in

North African countries with the price in the UK, as reported by

the World Bank. In 2012, the average price for gasoline in the UK

was US$ 2.17/ltr, above the prices in all of the North Africa

countries, usually by orders of magnitude: 4.8 times as high as the

Egyptian price, 7.5 times as high as the Algerian price, and even 18.1

times as high as the Libyan price of a mere 12 cents/ltr. As noted,

oil and gas revenues overwhelmingly dominate the government

budgets in Libya and Algeria. These two countries have the most

heavily subsidised gasoline in the region, with gasoline priced at

only US$ 0.12/ltr in Libya and US$ 0.29/ltr in Algeria.

Figure 3 compares the pump price of diesel in North Africa

with the price in the UK. The US$ 2.27/ltr price in the UK in 2012

was 13.4 times as high as the Algerian price of

US$ 0.17/ltr and 22.7 times as high as the US$ 0.10/ltr seen

in Libya.

Resource governance

Petroleum and natural gas are critical to the North African

economy. Yet the presence of oil and gas reserves may not

translate directly into economic health, even in countries

considered resource rich. A group known R-S the Revenue Watch

Institute recently released their report, The 2073 Resource

Governance Index. The Resource Governance Index, or RGI, was

developed to evaluate the governance of the oil, gas and mining

industries in 58 countries. These 58 countries produce 85% of the

world's oil, 80% of the world's copper and 90% of the world's

diamonds .. The premise is that good governance of resource

extraction industries is critical to long term economic success. The

evaluation criteria were organised into categories of Institutional

and Legal Setting, Reporting Practices, Safeguards and Quality

Controls, and Enabling Environment. Despite the importance of

resource' extraction in North Africa, Algeria received a 'failing'

score of 38, ranking 4st

h

out of the 58 countries. Egypt received a

'weak' score of 43, placing 38

th

out of 58 countries. Morocco

received a 'partial ' score of 53, ranking 25

th

out of 58 countries.

Libya received a 'failing' score of19, ranking 55

th

out of 58

countries. The report noted that Libya's very low scores on all

,

0.7 +-\:------------------- -=j

0.6

0.5

0.4 -I--- - ---------------- -----"'\--+i

0.3 t---------------------------j

- North Aftica Gas Production % of

0.2 Total Africa

- North Africa Oil Production % of

0.1 Total Africa

Figure 7. North Africa's falling share of African oil

and gas output.

measures reflected decades of corruption and inefficiency,

obviously a difficult system to reform.

On the whole, however, the RGI study establishes that

resource governance is difficult around the world, not just in North

Africa. The Resource Watch group concluded that '80% of

governments fail to achieve good governance in their extractive

sectors'. Yet while North Africa is not alone in grappling with this

problem, the consequences in this region have been severe, and

there is little doubt that poor governance of the oil and gas

industry is part and parcel of the overall poor governance that

fomented the Arab Spring protests. Logically, therefore, it is

doubtful that the political and economic reforms now underway

will be able to succeed without serious attention given to the oil

and gas sectors.

Losing ground: Oil and gas reserves

Oil was discovered in Algeria in 1956, shortly befc;>re the Suez Crisis.

Oil was discovered in Libya in 1959. Libya joined OPEC in 1962, and

Algeria joined in 1969. North African oil and gas resources were

viewed historically as a strategic alternative to Persian Gulf

producers. Oil exports had the added advantage that Suez Canal

transit was not required to reach the markets of Europe and the

Americas. North Africa quickly became a premier oil centre, with a

host of foreign companies participating. But its dominance is

waning, and investment is needed or it will continue to lose

ground.

North African proved oil reserves by country, January 2013, are

shown in Figure 4, as reported by the Oil and Gas Journal (OGJ).

Libya's oil reserves account for nearly three quarters of the regional

total, at 48 billion bbls. Algerian reserves also are considerable at

12.2 billion bbls, followed by Egypt, with reserves listed at 4.4 billion

bbls. For the five countries, total oil reserves are 64.9 billion bbls,

slightly more than half of total African continent oil reserves.

Algeria, Libya and Egypt also possess the majority of North

Africa's natural gas resource, approximately 54% of which is located

in Algeria, followed by 26% in Egypt. Figure 5 shows North Africa's

proved gas reserves as reported by OGYUntil recently, natural gas

reserves had been growing significantly, particularly with new finds

in Egypt. Egypt launched LNG exports in 2005, exporting 7.6 billion

m

3

that year. Libya's national oil company had been working to

expand natural gas reserves, and it hoped to nearly double reserves

to 100 trillion ft3, but the civil war derailed these plans.

In recent years, North Africa's additions to oil and natural gas

reserves have lagged relative to the rest of the world. According to

Hi-Force HTP, AHP & ATOP Hydrotest Pumps

HTP Manually Operated Hydrotest Pumps

Working pressures up to 1 000 Bar

> > Two stage with semi automatic

pressure changeover

> > Lightweight aluminium design with

15 litre reservoir capacity

AHP Air Driven Hydrotest Pumps

Output pressures up to 2931 Bar

> > Chart recorder available as standard

in AHP-CR and AHP2-CR models

> > Choice of standard, medium and high

flow models

ATOP Air Driven Hydrotest Pumps

> > Output pressures up to 1489 Bar

Twin double acting design offering

high volume flow

> > Infinitely variable output pressure and

flow

AHP58

ATDP125

IHil1!liWlll www.hi-force.com

1.6

1.41

1.43 1.42

1.38

1.4

1.28 1.29 1.3 1.31

1.27 1.26

1.2

............ ,

1}6

1.18 116

"5 1.!.

.

\

I

[ 0.8

,

0.7 0.69 0.69

0.68r 0.68 0.68

0.67..___

U. 1l

0.6

0.57

\

0.4

\ /

- Algeri a - Eeypt - libya

0. 2

Figure 8. Recent North African crude production.

Figure 9. North African crude/ NGL production

trend, 1965 - 2012.

100

80

, 60

40

20

Figure 10. North Africa falling share of African

natural gas output.

l as

I

- Algeria - Egypt - libya _______ --="""""'"-=--________ ---'

10

Figure 11. Dwindling North Africa LNG exports.

December 2013

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

the data series maintained by BP, North Africa's share of global gas

reserves was fairly steady at approximately 5% from 2003 to 2007.

However, during the five years from 2007 to 2012, North Africa's

share has fallen to 4.3% of global reserves. North Africa's share of

global oil reserves had been on an upward trend, growing from 4.1%

in 2003 to 4.3% in 2007, but this share fell to 3.9% in 2012. These

falling shares are shown in Figure 6.

Oil and natural gas production: Also flagging

As North Africa's share of oil and gas reserves have fallen, oil and

natural gas production has fallen also. Figure 7 shows North Africa's

falling share of output relative to total African output. In 1970,

North Africa produced 92% of total African natural gas plus 79% of

African crude oil. These shares have fallen conSiderably. By 2012,

North Africa accounted for 71% of the continent's natural gas

output and only 42% of the crude output. In 2011, the drop in

Libyan crude production had caused North Africa's share to drop

to just 34%.

Figure 8 provides a closer look at the impact of the Libyan civil

war on oil production by displaying quarterly production as

reported by the International Energy Agency (lEA). In the first

quarter of 2011, Libyan output was 1.13 million bpd. By the second

quarter, it had plummeted to 0.12 million bpd, and it fell to a mere

trickle of 0.04 million bpd in the 3

rd

quarter. By October, Sirte had

fallen and Colonel Qaddafi had been slain. Crude production

began to be restored, and it averaged 0.57 million bpd in the

fourth quarter. In 2012, output hit a peak ofl.43 million bpd before

subsiding to 1.31 million bpd in the second quarter of 2013. Libyan

officials affirm that they will be able to boost crude production to

2 million bpd by 2017. By the third quarter of 2013, however,

output fell once again, as striking workers blocked Sharara and

Elephant oil fields and terminals in western Libya. This helped to

drive up the international oil price. As of the time of this writing,

an agreement has been reached that is intended restore Libyan

production.

Algerian crude production was in the range of

1.26 - 1.28 million bpa in 201l, but it fell to 1.14 million bpd in the

second quarter of 2013. Egyptian crude production declined

modestly from 0.7 million bpd in the first quarter of 2011 to

0.67 million bpd in the third quarter of 2012, but it recovered and

averaged 0.72 million bpd in the second quarter of 2013.

Figure 9 shows the long term trend in crude and NGL

production for the four main North African producers,

1965 - 2012, per BP. Libyan production hit a.peak of nearly

3.4 million bpd in 1970, but output collapsed to 1.0 million bpd in

1987. When sanctions were lifted in 2003, some international firms

returned to Libya, and production rose to 1.8 million bpd by 2006

- 2008. The impact of the civil war is starkly visible in 2011,

followed by a recovery in output in 2012.

Algerian production reached 1.0 million bpd in 1970, and it

neared 2.0 million bpd from during the 2005 - 2008 period. Some

of the strength in liqUids output has been the result of increased

natural gas production and processing. Output fell to 1.67 million

bpd in 2012. Egyptian oil production was only 0.1 million bpd in

1965, but output began to grow in the late 1970s, reaching a peak

of 0.94 million bpd in 1993. Production trended down gently until

2005, when the production decline was reversed. Output in 2012

was approximately 0.73 million bpd. Tunisian output has been

roughly stable in the range of 70 000 - 80 000 bpd over the past

decade, though recent years have shown a slight downturn.

Algeria 5 497 15 0 6

Egypt 9 794 95 39 0

Libya 5 378 4 0 0

Morocco 2 155 27 0 5

Tunisia 34 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

Total 22 1858 140 39 11

Cracking: Distillation ratio 4.5%

80r----------------------------------------,

70

6 0 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

20 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

10 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Figure 12. North Africa active rotary rigs, monthly

2007 - 2013.

Other a tuclOil

Oiesel

- Gasoline

g

: 2S0 1------1.''''

~

libya Output 2011 li bV;l Demand lOll

Figure 13. Libyan refined product output versus

demand.

North Africa is the key natural gas producing region in

Africa, but as is the case with oil, its overall share of production

is declining. Figure 10 shows natural gas production in Algeria,

Libya and Egypt from 2002 through 2012, along with their

percentage share of total African output. Algeria is the main

producer, and its natural gas production had been trending

upward until the middle of the decade, when it stagnated and

began to slide. From its peak of 88.2 biHion m

3

in 2005, Algerian

production fell to 81.5 billion m

3

in 2012.

Egyptian gas production, as noted, had been growing

strongly, climbing from 27.3 billion m

3

in 2002 to 62.7 billion m

3

in 2009. This leveled off and declined slightly to 60.9 billion m

3

in 2012. Libyan output also had been expanding in the post

sanction years, reaching 15.9 billion m

3

in 2008, but production

stagnated by the late 2000s, and it dipped to 7.9 billion m

3

in

December 2013

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

0 90 0 0 83 3 5

34 84 9 27 208 8 20

0 20 0 0 43 3

0 27 0 0 53 2 2

0 3 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0

34 224 9 27 387 14 30

2011 before recovering somewhat to 12.2 billion m

3

in 2012.

Overall, in 2002, these three natural gas producers accounted

for 82% of African output, but their share fell to 71 % in 2012.

Egypt started exporting LNG in 2005. Exports rose to

14.8 billion m

3

in 2006, but soon they began to slide, and by

2012 Egyptian LNG exports totaled only 6.7 billion m

3

. Algeria

is the premier LNG exporter in the region, but its LNG exports

have also fallen steadily. Algeria exported 27.9 billion m

3

of

LNG in 2003, but exports fell to 15.3 billion m

3

in 2012. Figure

11 illustrates this decline. In 2004, Algerian LNG exports of

24.8 billion m

3

were slightly larger than Qatari exports of

24.1 billion m

3

. By 2012, Qatar's growth in LNG exports had

eclipsed not only Algeria but all of North Africa, amounting

to 105.4 billion m

3

, 6.9 times as much as Algerian exports and

4.8 times as much as total North African exports.

In early 2002, spot prices for Brent crude oil were in the

vicinity of US$ 20/bbl. They marched upward and spiked at

approximately US$ 133 for the month of July 2008. Much of

the world fell into recession, and Brent spot prjces collapsed

by late 2008. Yet prices recovered, and they have remained at

over US$ 100/ bbl since early 20ll. This type of price horizon

has stimulated a great deal of interest in exploration and

production. Much of the enthusiasm has bypassed North

Africa, however. Figure 12 displays the number of active

drilling rigs in Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia each month

from January 2007 through August 2013, as tracked by Baker

Hughes. Although oil prices were rising strongly in the 2007 -

2008 period, the number of active rigs increased noticeably

only in Egypt. When the oil price collapsed in late 2009,

active rigs in Egypt fell. When prices began to recover, the

number of active rigs in Egypt recovered as well. Yet despite

the continued strength of oil prices, the number of active rigs

leveled off and began to fall in 2012, in conjunction with the

rise in political unrest and the ousting of the newly elected

President.

Tunisia typically has had only three to five rotary rigs

active, but in August 2013, only one rig remained active. From

2007 until early 2011, Libya had 10 - 20 active rigs, and this

dropped to zero during the civil war. Rigs were reactivated

since then, and there were 15 active as of August 2013. Algeria

has seen a recent rise in active rigs, which had been in the

range of 25 - 30 for most of 2000 through 20ll. In August 2013,

Baker Hughes reported 49 active rigs. Perhaps not

coincidentally, the Arab Spring protests did not unseat the

head of state, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who has ruled since 1999.

Despite suffering a stroke earlier in 2013, he remains in power,

and many believe that he will be able to hand pick a successor

when elections are held next in April 2014.

The oil and gas sectors remain highly active, therefore, but

they are losing ground relative to competitors at a time when

they could be growing. Governments have been taking steps to

increase international participation, but some investors are wary.

For example, Algeria amended its hydrocarbon laws in early 2012 to

attract more foreign investment, and Parliament approved the

changes in January 2013. But this progress was set back by militant

attacks on Algeria's Amenas LNG plant, which claimed over 60

militant and worker lives and shut down the facility. The Amenas

plant is located inland and near the border with Libya, raising

security concerns. In fact, some of the recent interest in exploration

and development in Morocco, which is far less oil and gas prone

than many areas in Algeria and Libya, has stemmed from the idea

that Moroccan installations will be safer.

North Africa's refining industry

Recent events have affected refinery plans

Mirroring the situation seen in the upstream oil and gas sector,

the social and political changes sweeping North Africa also have

detracted from the downstream sector. There have been a

number of refinery upgrades, expansions, and even grassroots

projects planned in North Africa, but the past two years have

proven challenging, and many projects have been postponed or

shelved. Algeria, for example, developed an ambitious

downstream plan that includes rehabilitation and expansion of its

three largest refineries (Arzew, Algiers, and Skikda), a condensate

splitting refinery at Skikda, a fuel oil conversion unit at Skikda

Energy Global

Bringing you the power of information

RSSfeed,simp!yc!]c

00 lho orange blJlIOf

and load the URL in!

your news rcaaeror

___ Other Fuel Oil

Di esel - Kerosene

Gasoline

177.1

67.4

AtgeriaOut put Algeria Demand

Figure 14. Algerian refined product output versus

demand.

(80 000 bpd capacity,) and four new grassroots refineries now

envisioned at 100 000 bpd each. Over the past two years, most

efforts have focused on the Skikda refinery, which often has

been closed or running at low utilisation rates during

maintenance and upgrades. These are planned to add 30 000

bpd of nameplate capacity, a catalytic reformer, and a

hydrotreater. There have been a variety of technical problems,

unfortunately, plus a fire and an explosion, and gasoline imports

have grown. As of the third quarter of 2013, Skikda's crude

capacity was increased to 335 000 bpd, and crude runs are

expected to rise for the remainder of the year. The Arzew

refinery also has been partially shut down for maintenance and

repairs in 2011 and 2012, which reduced gasoline output. The

~

ABUTECTM

Advanced

Burner

Technol ogi es

---- www. abutec.com ----

SPECIALIZING IN HIGH-EFFICIENCY, LOW-EMISSION

ENCLOSED COMBUSTORS TO THE OIL 6 GAS INDUSTRY

MIDSTREAM

UPSTREAM

Quad 0 Compliant

Combustion Devices

>98% DRE

Customizable Vapor Control Systems

99.9% DRE

address 112959 Cherokee Street,

Suite 101, Kennesaw, GA 301 44

email Ilinfo@abutec.com

phone 11 770.846.01 55

Soralchin refinery reportedly reduced its runs in 2012 over

disputes concerning profitability.

Libya's Ras Lanuf refinery also has been run at low

utilisation rates since the civil war, with problems getting

crude deliveries and disagreements between the

government and the refinery operator. At 220 000 bpd, Ras

Lanuf is Libya' s largest refinery. Some of the protests in

2012 resulted in a blockade of the Ras Lanuf port. The Ras

Lanuf refinery reopened in late 2012, but closed again in

early 2013 because of technical problems at the refinery,

power outages, plus a strike by workers at the Port. There

was also a brief shutdown at the Zawiya refinery, caused by

a worker' s strike. Libyan officials have announced that they

will expand Libya's refinery capacity from its current 0.38

million bpd to 1 million bpd within the next six years, but

even the capacity that now exists is subject to closure or

low utilisation rates because of security concerns along the

supply chain.

Table 2 provides a summary of North Africa's refining

industry, partly as reported by OGJ with additions and

corrections provided by Trans-Energy Research Associates,

Inc. Total crude capacity is 1 858 000 bpd. The industry

lacks technological sophistication, with a cracking to

distillation ratio of only 4.5%. North Africa's refining sector

remains in need of investment and attention to raise its

sophistication and competitiveness. The region' s refining

industry is long established, but it more or less operated in

the same business environment as the upstream sector, and

it too would benefit from more investment and more

openness. As an example, consider the capability of the

Algerian and Libyan refining industries to meet domestic

demand.

Algerian and Libyan refinery output

versus demand .

As noted, all of the North African oil producing countries

subsidise domestic fuel prices, Libya and Algeria to an

extreme degree. The Libyan gasoline price was only

12 cents/ltr in 2012, and diesel prices were only 10 cents/

ltr. Algerian gasoline was priced at 29 cents/ltr, while

diesel was priced at 17 cents/ltr. Unsurprisingly, the

demand pattern is skewed toward gasoline and diesel in

both countries. And despite the fact that nameplate

refinery capacity is greater than domestic demand, both

countries are net importers of gasoline and diesel. There

are plans to expand refinery capacity in both countries. But

it can be seen that it is not so mud') the amount of

capacity, but the type of capacity and how it is utilised,

that determines how well the industry will be able to meet

domestic demand.

Figure 13 compares refined product output with

product demand in Libya, and Figure 14 shows the same

information for Algeria, as reported by OPEC. Algerian

refined product output was 501 300 bpd in 2011, while

product demand was 329 400 a surplus of 171

900 bpd of refined product. Libyan refined product output

was 473 200 bpd, while demand was 231 400 bpd, leaving a

surplus of241 800 bpd. The surplus output is a rough

estimate of potential product exports. However, Algerian

output was only 41% gasoline plus diesel , whereas Algerian

demand was 74.2% gasoline plus diesel. Libyan refinery

December 2013

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

production was only 20.4% gasoline and diesel, whereas

the demand pattern was

78.1% gasoline and diesel. In net terms, therefore, Algeria

needed imports of 16 100 bpd of gasoline plus 22 800 bpd

of diesel. Libya needed 80100 bpd of gasoline imports and

4100 bpd of diesel imports. The exports were primarily

lower value products such as fuel oil. As noted, an

80000 bpd fuel oil conversion unit has been planned in

Algeria, as well as a condensate splitter, which would

create a lighter output slate, but many plans and goals have

been set back.

Conclusion: A weakening

breeze?

The winds, like a sirocco, have swept through North Africa,

bringing changes of leadership in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt

once again. This included an end to the infamous Qaddafi

regime in Libya. Protests and demonstrations have taken

place in Algeria and Morocco as well. The ageing president

of Algeria held on to power, but may hand over the reins

to a successor in early 2014. The King of Morocco allowed

peaceful demonstrations and has made many concessions

toward more open government. Throughout North Africa

and in the Middle East, this movement became known as

the 'Arab Spring' . The situations vary from country to

country, but there are many commonalities in what the

people are protesting: high levels of unemployment, a

widening gap between rich and poor, crime, violence, and

corruption. The people's disaffection stems from a long

standing failure of the governments to deliver on promises.

Some of the economic problems, however, were

exacerbated by the global economic downturn, which local

governments were powerless to combat. Other social and

political ailments were so deeply rooted that reforms will

come only slowly. After the first whirlwind of change, the

slow pace of reform and rebuilding has caused frustration,

leading observers to speak of how the 'Arab Spring' turned

into the 'Islamist Winter'.

North Africa's oil and gas sector is critically important

to the region's economic health, and also to government

stability and basic function, since the governments run the

energy industry and derive a major share of their operating

revenue from it. Yet for all of its importance, the North

African governments receive very poor 'grades' when it

comes to how they manage their resources. When

evaluated according to the criteria of the Resource

Governance Index, the two main producers, Libya and

Algeria, received failing scores, and Egypt received a 'weak'

score. Libya ranked 55

th

out of 58 countries examined, with

consistently low scores attributed to decades of

mismanagement and corruption. Yet in a way there is cause

for optimism. The same inefficiency and corruption that

typified the energy industry was endemic across the

government, and this was its eventual undoing. The new

regimes hope to change this and build stronger, healthier

economies, and the same principles that improve overall

governance of the countries will improve governance of

the energy industries. Although the changes may take time,

and the sirocco winds may have weakened, it can be hoped

that a gentler breeze will fill the sails and transport North

Africa's energy' sector to smoother seas. ill

,

I

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Salary Guide 2013Document17 pagesSalary Guide 2013sorin_1234No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Artic UpstreamDocument4 pagesArtic Upstreamgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Salary Guide 2013Document17 pagesSalary Guide 2013sorin_1234No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Indias Leadership ChallengeDocument5 pagesIndias Leadership Challengegweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Management Standards' and Work-Related Stress AnalysistoolmanualDocument36 pagesManagement Standards' and Work-Related Stress Analysistoolmanualgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- OMG - Product Lifecycle Management ServicesDocument399 pagesOMG - Product Lifecycle Management Servicesgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Chevron's Four Steps To Business SuccessDocument1 pageChevron's Four Steps To Business Successgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Australian Natural GasDocument5 pagesAustralian Natural Gasgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A New Way To Measure Word-Of Mouth MarketingDocument9 pagesA New Way To Measure Word-Of Mouth MarketingsoortyNo ratings yet

- Refinery Configurations For Maximising Middle Distillates Lc-FinerDocument8 pagesRefinery Configurations For Maximising Middle Distillates Lc-Finergweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- HSE Loss of Containment Manual 2012Document68 pagesHSE Loss of Containment Manual 2012gweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- BWR Vessel and Internals ProjectDocument236 pagesBWR Vessel and Internals Projectgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Prices Sept 2012Document7 pagesPrices Sept 2012gweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Refinery Configurations For Maximising Middle Distillates Lc-FinerDocument8 pagesRefinery Configurations For Maximising Middle Distillates Lc-Finergweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- WeibayesZero FailureCalculatorDocument14 pagesWeibayesZero FailureCalculatorgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- 10.03.03 Asia Economic Insight HSBCDocument13 pages10.03.03 Asia Economic Insight HSBCbocalaRONo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Gulf Oil Spill: Presidential Commission Releases Final Report On BP and Deepwater Horizon SpillDocument398 pagesGulf Oil Spill: Presidential Commission Releases Final Report On BP and Deepwater Horizon SpillPublicNo ratings yet

- Schein Organizational SocializationDocument89 pagesSchein Organizational Socializationgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- IEA 2012 Refining ForecastDocument2 pagesIEA 2012 Refining Forecastgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey A Consumer Paradigm For ChinaDocument9 pagesMcKinsey A Consumer Paradigm For ChinaDenis OuelletNo ratings yet

- 2010 Deepwater Solutions & RecordsDocument1 page2010 Deepwater Solutions & Recordsgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CPV World Map 2011: Concentrated Photovoltaic Summit USA 2011Document5 pagesCPV World Map 2011: Concentrated Photovoltaic Summit USA 2011gweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey - A Marketer's Guide To BehavioralDocument4 pagesMcKinsey - A Marketer's Guide To Behavioralgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey On Government 2009Q2Document9 pagesMcKinsey On Government 2009Q2gweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey On Finance 2009Q2Document5 pagesMcKinsey On Finance 2009Q2gweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey - A CEO's Guide To Reenergizing The Senior TeamDocument7 pagesMcKinsey - A CEO's Guide To Reenergizing The Senior Teamgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey - A Better Way To Cut CostsDocument4 pagesMcKinsey - A Better Way To Cut Costsgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- McKinsey On Oil & GasDocument8 pagesMcKinsey On Oil & Gasgweberpe@gmailcomNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- How Inflation Can Destroy Shareholder Value - Feb 2010Document6 pagesHow Inflation Can Destroy Shareholder Value - Feb 2010qtipxNo ratings yet

- La Toponymie en Algérie Ahmed Chikhi Et Naila ChikhiDocument6 pagesLa Toponymie en Algérie Ahmed Chikhi Et Naila ChikhiZemmouri HoussamNo ratings yet

- Algeria at The Crossroad of CivilizationsDocument1 pageAlgeria at The Crossroad of CivilizationsSouad Guess100% (3)

- The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa / by Harry W. HazardDocument483 pagesThe Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa / by Harry W. HazardDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (4)

- Mas. Amz. 581Document54 pagesMas. Amz. 581Nabila AidoudNo ratings yet

- Conversations With Camus As Foil, Foe and Fantasy in Contemporary Writing by Algerian Authors of French ExpressionDocument20 pagesConversations With Camus As Foil, Foe and Fantasy in Contemporary Writing by Algerian Authors of French ExpressionBoabaslamNo ratings yet

- Ms Ms Am Am Xa Exa /ex M/e M/ Om/ Com Co Co N C N. Ion Tion Tio Ati Cat Ca Uca Duc Duc Du Ed Ed Y-E Y-E Cy Cy Cy NC eDocument3 pagesMs Ms Am Am Xa Exa /ex M/e M/ Om/ Com Co Co N C N. Ion Tion Tio Ati Cat Ca Uca Duc Duc Du Ed Ed Y-E Y-E Cy Cy Cy NC eFat H100% (1)

- Gard List of Correspondents 2016Document116 pagesGard List of Correspondents 2016Tanvir ShovonNo ratings yet

- Iba PDFDocument715 pagesIba PDFLuzNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Composition and Culture in West EuropeDocument30 pagesEthnic Composition and Culture in West EuropeAnother OneNo ratings yet

- rp215 BentouhamiDocument13 pagesrp215 BentouhamivvhirondelleNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A Slave Between Empires: A Transimperial History of North AfricaDocument247 pagesA Slave Between Empires: A Transimperial History of North AfricaWajihNo ratings yet

- عادات الجزائر بالانجليزيةDocument5 pagesعادات الجزائر بالانجليزيةTamer Tamer MetNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Arts & Sciences and MIT Press Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To DaedalusDocument21 pagesAmerican Academy of Arts & Sciences and MIT Press Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Daedalusj_pambelumNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 2023 2024Document6 pagesLesson Plan 2023 2024Bouguelimina IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Tanfalit Tutlayant N Wadeg I Yettwazedɣen Taqbaylit (Draɛ El Mizan) Tacawit (Inuɣisen) Tazrawat TasnalɣamkantDocument91 pagesTanfalit Tutlayant N Wadeg I Yettwazedɣen Taqbaylit (Draɛ El Mizan) Tacawit (Inuɣisen) Tazrawat TasnalɣamkantAmurukuch N TimmuzghaNo ratings yet

- RESUME MEP ENGINEER HVAC ELEC ZAHAF SadekDocument3 pagesRESUME MEP ENGINEER HVAC ELEC ZAHAF Sadekdelta conceptNo ratings yet

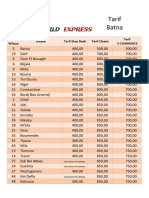

- Tarif Batna: Code Wilaya Wilaya Tarif Stop Desk Tarif Classic Tarif E-CommerceDocument2 pagesTarif Batna: Code Wilaya Wilaya Tarif Stop Desk Tarif Classic Tarif E-CommerceMBT TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Language-In-education Planning in Algeria - Historical Development and Current IssuesDocument28 pagesLanguage-In-education Planning in Algeria - Historical Development and Current Issuesharaps22100% (3)

- Moving Towards A North African Pharmaceutical MarketDocument102 pagesMoving Towards A North African Pharmaceutical Marketmamsi mehdiNo ratings yet

- المنطقـة المستقلـة خلال - معركـة الجزائــر - أوت 1956 أكتوبر 1957Document19 pagesالمنطقـة المستقلـة خلال - معركـة الجزائــر - أوت 1956 أكتوبر 1957Nur UhoNo ratings yet

- Algeria TemplatesDocument19 pagesAlgeria TemplatesADrian ZeeGreatNo ratings yet

- Mohamed Bendjebbar ResumeDocument2 pagesMohamed Bendjebbar ResumeWhite Wolf SenpaiNo ratings yet

- Social Life V2Document11 pagesSocial Life V2Moses KimaniNo ratings yet

- Goytisolo The Linguistic Fracture of The MaghrebDocument4 pagesGoytisolo The Linguistic Fracture of The MaghrebpomerangeNo ratings yet

- Algerian Life Style: - Between The Past and The PresentDocument13 pagesAlgerian Life Style: - Between The Past and The PresentD A L E LNo ratings yet

- Nedma: BooksDocument396 pagesNedma: BooksTugba YurukNo ratings yet

- Mock Exam by Mrs - BENGHALIADocument2 pagesMock Exam by Mrs - BENGHALIADonna HarveyNo ratings yet

- Assia Djebars Short Stories and Women-LibreDocument8 pagesAssia Djebars Short Stories and Women-Libreنجمةالنهار100% (1)

- IDRICI Nabila TM. 186Document246 pagesIDRICI Nabila TM. 186Sima KadiNo ratings yet

- Can Algeria Send Money Through Western UnionDocument1 pageCan Algeria Send Money Through Western UnionMeriem OuyahiaNo ratings yet

- Practical Reservoir Engineering and CharacterizationFrom EverandPractical Reservoir Engineering and CharacterizationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Well Integrity for Workovers and RecompletionsFrom EverandWell Integrity for Workovers and RecompletionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Pocket Guide to Flanges, Fittings, and Piping DataFrom EverandPocket Guide to Flanges, Fittings, and Piping DataRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (22)

- Internal Combustion: How Corporations and Governments Addicted the World to Oil and Subverted the AlternativesFrom EverandInternal Combustion: How Corporations and Governments Addicted the World to Oil and Subverted the AlternativesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)