Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rosen Symbol of Tree

Uploaded by

jesprileCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rosen Symbol of Tree

Uploaded by

jesprileCopyright:

Available Formats

THE SYMBOL OF THE TREE IN INDIAN SPIRITUAL LITERATURE In the bottomless [abyss] king Varuna By the power of his

pure will upholds aloft The [cosmic] trees high crown. There stand below [The branches], and above the roots. Within us May the banners of his light be firmly set! --Rig Veda 1.24.7. When Alexander the Great reached the furthest forests of India the inhabitants led him, in the dead of night, to an oracular tree which could answer questions in the language of any man who addressed it. The trunk was made of snakes, animal heads sprouted from the boughs, and it bore fruit like beautiful women, who sang the praises of the Sun and the Moon. According to Pseudo-Callisthenes, the tree warned Alexander of the futility of invading India with the intent to obtain dominion over it. Known as the Waqwaq Tree in Islamic tradition, it was often portrayed on Harappan seals four millenia ago as sprouting heads of a bovine unicorn, encircling a female divinity, or even growing from her body. The association of India with oracular trees bearing strange fruit derives from tales of the tree-worship which has flourished there since remote antiquity. European maps of India Ultima from the twelfth century and later show the Speaking Tree. --Richard Lannoy, The Speaking Tree: A Study of Indian Culture and Society, xxv. As a tree of the forest, Just so, surely, is man. His hairs are leaves, His skin the outer bark. His pieces of flesh are under-layers of wood. The fibre is muscle-like, strong. The bones are the wood within. The marrow is made resembling pith. If with its roots they should pull up The tree, it would not come into being again. A mortal, when cut down by death-From what root does he grow up? --Brihad-Aranyaka Upanishad, Man, a Tree Growing From Brahma, 3.9.28. Its root is above, its branches below-This eternal fig-tree! That [root] indeed is the Pure. That is Brahma. That indeed is called the Immortal. On it all the worlds do rest, And no one soever goes beyond it. --Katha Upanishad, the World Tree Rooted in Brahma, 6.1.

Indian tradition, according to its earliest writings, represents the cosmos in the form of a giant tree. This idea is defined fairly formally in the Upanishads: the Universe is an inverted tree, burying its roots in the sky and spreading its branches over the whole earth . .. --Mircea Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion, 272. With roots above and boughs beneath, they say, the undying fig- tree [stands]: its leaves are the Vedic hymns: who knows it knows the Veda. Below, above, its branches straggle out, well nourished by the constituents; sense-objects are the twigs. Below its roots proliferate inseparably linked with works in the world of men. No form of it can here be comprehended, no end and no beginning, no sure abiding-place: this fig-tree with its roots so fatly nourished--[take] the stout axe of detachment and cut it down! --Bhagavad Gita, the Cosmic Fig-Tree, 15.1-3. In the Bhagavad-Gita, the cosmic tree comes to express not only the universe, but also mans condition in the world . . . The whole universe, as well as the experience of man who lives in it and is not detached from it, are here symbolized by the cosmic tree. By everything in himself which corresponds with the cosmos or shares in its life, man merges into the same single and immense manifestation of Brahman. To cut the tree at its roots means to withdraw man from the cosmos, to cut him off from the things of sense and the fruits of his actions. --Mircea Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion, 272-273. Indian tradition has always visualized the human body as growing like a plant from the ground of the beyond, the Supreme Brahman, the Truth. And just as the vital juices of a plant are carried up and outwards from the root through the channels and veins, so are the creative energies in the human body. Only the root of the human plant is not below, but above, beyond the top of the skull over the spine. The nourishing and bewildering energy flows in from beyond at that point. After spreading along the through the bodys channels it flows to the outermost tips of the senses, and even further out, to project the space around it which each body believes it inhabits. The pattern of veins and channels which compose this system is called the subtle body and is the basis of all Tantric worship and yoga. --Philip Rawson, Tantra: The Indian Cult of Ecstasy, 20-21. Mans life in this relative world may be compared to a tree. Tamas is the seed. Identification of the Atman with the body is its sprouting forth. The cravings are its leaves. Work is its sap. The body is its trunk. The vital forces are its branches. The senseorgans are its twigs. The sense-objects are its flowers. Its fruits are the sufferings caused by various actions. The individual man is the bird who eats the fruit of the tree of life. --Shankara, Crest-Jewel of Discrimination. Mind is the seed, pranayama the soil, dispassion [vairagya] the water. Out of these three grows the tree that fulfills all wishes. --Swatmarama, Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 4.104.

In Kundalini yoga the tree represents the spine or nervous system, the central axis of the universe which carries the serpent, or the Kundalini, to the crown, the top chakra in the head where the mythical eagle Garuda carries the serpent off into the air. --Arnold Mindell, Dreambody, 61. When the Blessed One, in the last watch of the Night of Knowledge, had fathomed the mystery of dependent origination, the ten thousand worlds thundered with his attainment of omniscience. Then he sat cross-legged for seven days at the foot of the Bo-tree (the Bodhi tree, the Tree of Enlightenment), on the banks of the river Nairanjana, absorbed in the bliss of his illumination. And he revolved in his mind his new understanding of the bondage of all individualized existence; the fateful power of the inborn ignorance that casts its spell over all living beings; the irrational thirst for life with which everything consequently is pervaded; the endless round of birth, suffering, decay, death, and rebirth. Then after the lapse of those seven days, he arose and proceeded a little way to a great banyan-tree, The Tree of the Goatherd, at the foot of which he resumed his crosslegged posture; and there for seven more days he again sat absorbed in the bliss of illumination. After the lapse of that period, he again arose, and, leaving the banyan, went to a third great tree. Again he sat and experienced for seven days his state of exalted calm. This third tree . . . was named The Tree of the Serpent King, Muchalinda. --Heinrich Zimmer, Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization, 66-7. On a banyan in full fruit a single fruit will ripen and of its seeds but few will sprout. Yet one of these will reach such height that travelers will seek it as a mother to ease their weariness. --Shalika. The wind that blows from the sandal trees of Malabar, the sweet sound of cuckoos, and the bower vines raise waves within the hearts of men, raise yearning. --Shrikantha. The trees come up to my window like the yearning voice of the dumb earth. Be still, my heart, these great trees are prayers. --Rabindranath Tagore, Stray Birds.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Art of Selling by Chris MayerDocument2 pagesArt of Selling by Chris MayerjesprileNo ratings yet

- Mediation Script.Document2 pagesMediation Script.AdimeshLochanNo ratings yet

- Jurgen Hanneder - Vedic and Tantric MantrasDocument21 pagesJurgen Hanneder - Vedic and Tantric MantrasjesprileNo ratings yet

- Restaurant Training Manuals: Bus ManualDocument15 pagesRestaurant Training Manuals: Bus ManualKehinde Ajijedidun100% (1)

- Hyundai Technical Training Step 2 New Alpha Automatic Transmission A4cfx 2009Document2 pagesHyundai Technical Training Step 2 New Alpha Automatic Transmission A4cfx 2009naomi100% (48)

- Yoga BooksDocument1 pageYoga BooksPiers Rossouw50% (2)

- Meausing A MoatDocument73 pagesMeausing A MoatjesprileNo ratings yet

- Theories of MotivationDocument8 pagesTheories of Motivationankushsingh007100% (12)

- Yoga Reading ListDocument2 pagesYoga Reading ListjesprileNo ratings yet

- GRAMMAR POINTS and USEFUL ENGLISHDocument197 pagesGRAMMAR POINTS and USEFUL ENGLISHMiguel Andrés LópezNo ratings yet

- Investment Phase of Desire EngineDocument21 pagesInvestment Phase of Desire EngineNir Eyal100% (1)

- Estimating Land ValuesDocument30 pagesEstimating Land ValuesMa Cecile Candida Yabao-Rueda100% (1)

- Asahi Songwon Colors (NSE - ASAHISONG) - Jul'18 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthDocument9 pagesAsahi Songwon Colors (NSE - ASAHISONG) - Jul'18 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthjesprileNo ratings yet

- Ruchira Papers (NSE - RUCHIRA) - Mar'17 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthDocument7 pagesRuchira Papers (NSE - RUCHIRA) - Mar'17 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthjesprileNo ratings yet

- How Australia's Banks Became The World's Biggest Property AddictsDocument9 pagesHow Australia's Banks Became The World's Biggest Property AddictsjesprileNo ratings yet

- 'I Represent It All' - in Conversation With Microsoft's Satya NadellaDocument16 pages'I Represent It All' - in Conversation With Microsoft's Satya NadellajesprileNo ratings yet

- Anjani Portland Cement LTD (NSE - APCL) - May'19 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthDocument15 pagesAnjani Portland Cement LTD (NSE - APCL) - May'19 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthjesprileNo ratings yet

- Chaman Lal Setia Exports (BSE - 530307) - Nov'16 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthDocument8 pagesChaman Lal Setia Exports (BSE - 530307) - Nov'16 Alpha - Alpha Plus Stock - Katalyst WealthjesprileNo ratings yet

- 3-Sweep in Declaration - Annex IIDocument1 page3-Sweep in Declaration - Annex IIjesprileNo ratings yet

- Value Research Stock Advisor - Sterlite TechnologiesDocument32 pagesValue Research Stock Advisor - Sterlite TechnologiesjesprileNo ratings yet

- Sandwiches: Free Range Chicken SandwichDocument1 pageSandwiches: Free Range Chicken SandwichjesprileNo ratings yet

- Competitive Strategy Stock Selection IndiaDocument23 pagesCompetitive Strategy Stock Selection IndiajesprileNo ratings yet

- Mantra - The Primordial EnergyDocument224 pagesMantra - The Primordial Energyjesprile100% (2)

- Alpha PM Andy CroweDocument31 pagesAlpha PM Andy CrowejesprileNo ratings yet

- Yoga Sutras Pada 1Document4 pagesYoga Sutras Pada 1jesprileNo ratings yet

- A4 Curries Nutri InfoDocument1 pageA4 Curries Nutri InfojesprileNo ratings yet

- The Fed's Actions in 2008 - What The TranscriptsDocument15 pagesThe Fed's Actions in 2008 - What The TranscriptsjesprileNo ratings yet

- Yoga Sutras Pada 4Document3 pagesYoga Sutras Pada 4jesprileNo ratings yet

- Jesus in IndiaDocument3 pagesJesus in IndiajesprileNo ratings yet

- Yoga Sutras Pada 3Document4 pagesYoga Sutras Pada 3jesprile0% (1)

- Yoga Sutras Pada 2Document3 pagesYoga Sutras Pada 2jesprileNo ratings yet

- 3Document3 pages3Chandrakant BhirudNo ratings yet

- 43 Mile End - PlanDocument1 page43 Mile End - PlanjesprileNo ratings yet

- Open For InspectionDocument1 pageOpen For InspectionjesprileNo ratings yet

- Home DesignDocument1 pageHome DesignjesprileNo ratings yet

- Visaka Industries Buy Report 191212Document4 pagesVisaka Industries Buy Report 191212jesprileNo ratings yet

- Sociology: Caste SystemDocument21 pagesSociology: Caste SystemPuneet Prabhakar0% (1)

- Koro:: Entrance Songs: Advent Song Ent. Halina, HesusDocument7 pagesKoro:: Entrance Songs: Advent Song Ent. Halina, HesusFray Juan De PlasenciaNo ratings yet

- SP BVL Peru General Index ConstituentsDocument2 pagesSP BVL Peru General Index ConstituentsMiguelQuispeHuaringaNo ratings yet

- Classification of Malnutrition in ChildrenDocument2 pagesClassification of Malnutrition in ChildrenJai Jai MaharashtraNo ratings yet

- Environmental Politics Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesEnvironmental Politics Research Paper Topicszeiqxsbnd100% (1)

- Conflict of Laws (Notes)Document8 pagesConflict of Laws (Notes)Lemuel Angelo M. EleccionNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Performance Appraisal SystemDocument8 pagesThesis On Performance Appraisal Systemydpsvbgld100% (2)

- Aditya DecertationDocument44 pagesAditya DecertationAditya PandeyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Pronouns Substitution and Ellipsis - Oxford Practice Grammar - AdvancedDocument8 pagesChapter 6 - Pronouns Substitution and Ellipsis - Oxford Practice Grammar - AdvancedKev ParedesNo ratings yet

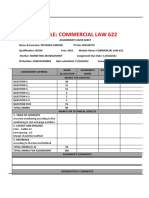

- Claw 622 2022Document24 pagesClaw 622 2022Priyanka GirdariNo ratings yet

- 富達環球科技基金 說明Document7 pages富達環球科技基金 說明Terence LamNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person Lesson 3 - The Human PersonDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person Lesson 3 - The Human PersonPaolo AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental ProfessionalsDocument8 pagesEndodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental Professionalsbobs_fisioNo ratings yet

- Gavin Walker, Fascism and The Metapolitics of ImperialismDocument9 pagesGavin Walker, Fascism and The Metapolitics of ImperialismakansrlNo ratings yet

- Tin Industry in MalayaDocument27 pagesTin Industry in MalayaHijrah Hassan100% (1)

- Maptek FlexNet Server Quick Start Guide 4.0Document28 pagesMaptek FlexNet Server Quick Start Guide 4.0arthur jhonatan barzola mayorgaNo ratings yet

- 4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisDocument13 pages4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisAnabel Marinda TulihNo ratings yet

- Kartilla NG Katipuna ReportDocument43 pagesKartilla NG Katipuna ReportJanine Salanio67% (3)

- Flinn (ISA 315 + ISA 240 + ISA 570)Document2 pagesFlinn (ISA 315 + ISA 240 + ISA 570)Zareen AbbasNo ratings yet

- Jas PDFDocument34 pagesJas PDFJasenriNo ratings yet

- PH 021 enDocument4 pagesPH 021 enjohnllenalcantaraNo ratings yet

- Drdtah: Eticket Itinerary / ReceiptDocument8 pagesDrdtah: Eticket Itinerary / ReceiptDoni HidayatNo ratings yet

- CO1 Week 3 Activities Workbook ExercisesDocument2 pagesCO1 Week 3 Activities Workbook ExercisesFrank CastleNo ratings yet