Professional Documents

Culture Documents

About Seamus Heaney

Uploaded by

espumagrisOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

About Seamus Heaney

Uploaded by

espumagrisCopyright:

Available Formats

Ply the Pen

By WILLIAM LOGAN

For a poet, life after the Nobel can be pottering, or bookkeeping, or simply keeping busy its rarely full of radical departures or stunning new poems. (Eliot called the prize a ticket to ones own funeral, and indeed it proved the funeral of his poetry.) Even pottering can be difficult when you are constantly in demand to judge this prize or sign that public letter, to give a blurb to old X or a recommendation to young Y. For a poet, all life can be a distraction from the siren call of the page. When you read that Seamus Heaney has a secretary to help him answer correspondence, you wish he had half a dozen, and perhaps a few armed guards. Yet apart from Pasternak, who was bullied by his government, no poet has ever turned down the poisoned chalice. Enlarge This Image

Jemimah Kuhfeld

Seamus Heaney Heaney is the most popular literary poet since Frost, who managed to convince most of his readers that he wasnt a literary poet at all, that he booted up poems while mucking out a spring or driving a buggy and perhaps, in a way, he did. Readers often love in Heaney what they loved in Frost, the unassumed and unassuming wisdom. Heaney has rubbed shoulders, as Frost did, with some of the most important literary figures of his day; Heaney has spent a long share of nights in hotels and on the road, as Frost did; yet often they write as if, just out the window, the cows were bawling to be milked and the first green shoots were sprouting in the fields and as if neither man had spent more nights in a hotel than the Queen of Sheba. In Human Chain, Heaneys latest collection, the poet is again a child in the world of things, his attention drawn to objects common as a coal sack: Not coal dust, more the weighty grounds of coal The lorryman would lug in open bags And vent into a corner,

A sullen pile But soft to the shovel, accommodating As the clattering coal was not. In days when life prepared for rainy days It lay there, slumped and waiting To dampen down and lengthen out The fire, a check on mammon And in its own way Keeper of the flame. This isnt lump coal, the top screening from the mine, but the bottom-deck slack coal, the cheap bits and grindings that fall through the other meshes. This refuse coal trims the cost of the fire (hence the mention of the Bibles Mammon). Keeper of the flame is its own droll joke, as if the coal, like the poet, honors the dead. Heaney is not a plain poet, at least not as plain as he seems the poems often have to be prodded and stirred to yield their meanings. At times the Ireland of Heaneys poems seems trapped in amber. The boom years of the Celtic Tiger and the bursting of the bubble afterward have made little impression on his work. Yet this love of the things of this world has made a world, even if one somewhat sealed off (Susan Sontag once said to an American novelist that he was living in his own theme park, and Heaneys Ireland is sometimes like Disney Dublin). Human Chain is a gallery of things of the binder and the baler (the clunk of a baler / Ongoing, cardiac-dull), of the heating boiler and the mite box and the gold-banded fountain pen, possessions that also possess, things that seize the people who use them, like the boy Who would ease his lapped wrist From the flap-mouthed cuff Of a jerkin rank with eel oil, The abounding reek of it Among our summer desks My first encounter with the up close That had to be put up with. Given the poet, given the future, its hard not to think that the Troubles lie there before him. That would suit his passive temper. At ease with forgotten manners, at ease with a sentence winding toward two final prepositions, Heaney manages to stiffen his syntax with an Anglo-Saxon rectitude of rhythm; yet where most poets live by eye, Heaney likes to press the readers nose into the carnal stench of things. This love of the way things work, this delight in the hard practical craftsman, is very different from Audens boyish romance with mining equipment. Auden loved such machines partly for the rust. Heaney likes to see a task efficiently done, and his poems are full of characters who know a job of work. Like Virgils Georgics, his poems offer a quiet master-class on how a farm used to be run, the homage of someone who returns again and again to the Irish fields that bore him.

Lick the pencil we might have called him So quick he was to wet the lead, so deft His hand-to-mouth and tongue-flirt round the stub. Or Drench the cow, so fierce his nostril-grab And peel-back of her lip, so accurately forced The bottle-neck between her big bare teeth. Or Catch the horse, for in spite of the low-set Cut of him, he could always slip an arm Around the neck and fit winkers on In a single move. Perhaps we give too much respect to a poetry lost in pastoral its the strain of Romanticism most palatable to contemporary taste (palatable, and often deeply conservative). A lot of modern poetry comes out of Wordsworths leech-gatherer, and at times Heaney drags in too many old grubbers with dirt under their thumbnails. Lewis Carroll wrote a howling parody of The Leech-Gatherer (later titled Resolution and Independence), and I doubt he would let the Irishman off any more lightly. Yet Heaneys nostalgia is rarely simple he understands the cost of love too well.

Heaney has Frosts avuncular voice, the bootstrap wisdom, the love of the natural world caught and rendered; yet hes not really a teller of tales, and his poems are slow to draw the homilies beloved by Frost the endings are hesitant, unrevealing, morally ambiguous. One of the great virtues of Heaneys poems is patience when he lingers over a description of a shopcoat, he gives the thing edge and weight. (Frost never paused for such descriptions and had an aversion to ingenious metaphor.) However much this is poetry, it is not poetry, the long-winded sentimental bombast that makes schoolchildren run screaming from poems ever after. HUMAN CHAIN By Seamus Heaney 85 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $24

Related

Books of The Times: Poetry Collections by Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon (September 17, 2010)

For decades Heaney has been a model citizen in the state of literature. He has produced useful translations (most popularly of Beowulf, a best seller), idiosyncratic anthologies, a respectable body of criticism and, every few years, a new book of poems. Hes unlikely to be remembered for more than the poems, and among the poems unlikely to be remembered for much written in the past 10 or 20 years. Theres a state of innocence poets need, a state hard to reach when theyve been frog-marched out of paradise to the memorial dinners and honorary degrees of experience. Many of Heaneys new poems start with the old flair and dash, but after a few lines they lose their way and sputter out. The late work has been solid, composed to a high level of craftsmanship; but

the poems are like footnotes to poems already written, with all of his mastery but little of his passion and less of his subdued outrage. They become that evil thing, poems written for the sake of writing poems. Human Chain is far from Heaneys best book the short and short-winded sequences rarely smolder like a peat bog afire underground. Hes still good at the character sketches from the Irish hinterlands, the deft evocations of common objects (the evidence of the ordinary bewitches him), the elegies and funerals that increasingly have dominated his work. Troubled by the losses memory is heir to, most moving on his fathers decline and death, the poems are evocations of a life now past. Heaney still has the great virtue of never saying too much, of letting the poem do so much work and no more. He can make buying a copy of Book VI of the Aeneid, that sturdy companion of young Latin scholars, as haunting as the visit to the Underworld within. For a poet of such ambition, Heaney has long given modesty a good name.

You might also like

- Elmer Rice The Adding MachineDocument29 pagesElmer Rice The Adding Machinekozemkojr982587% (31)

- Arabian Nights: The Book of the Thousand Nights and a NightFrom EverandArabian Nights: The Book of the Thousand Nights and a NightRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sikkens Technical Handbook ManualDocument140 pagesSikkens Technical Handbook ManualYudhisTira67% (3)

- Piet Mondrian PDFDocument104 pagesPiet Mondrian PDFeterno0% (1)

- Book Felicity Vii 11Document36 pagesBook Felicity Vii 11ancuta100% (2)

- Delphi Complete Works of Lord Byron (Illustrated)From EverandDelphi Complete Works of Lord Byron (Illustrated)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- War Rugs PDFDocument8 pagesWar Rugs PDFJulian derenNo ratings yet

- The WarsDocument5 pagesThe WarsNuvjeet GillNo ratings yet

- Asian PaintsDocument10 pagesAsian Paintsprahaladhan-knight-940100% (2)

- Delphi Collected Poetical Works of Walter Savage Landor (Illustrated)From EverandDelphi Collected Poetical Works of Walter Savage Landor (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- A Jongleur Strayed Verses on Love and Other Matters Sacred and ProfaneFrom EverandA Jongleur Strayed Verses on Love and Other Matters Sacred and ProfaneNo ratings yet

- The Early Poems of Alfred Lord Tennyson - Volume III: "Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all."From EverandThe Early Poems of Alfred Lord Tennyson - Volume III: "Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all."No ratings yet

- Elizabethan Sonnet CyclesPhillis - Licia by Fletcher, Giles, 1549?-1611Document69 pagesElizabethan Sonnet CyclesPhillis - Licia by Fletcher, Giles, 1549?-1611Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Elegy Written in A Country ChurchyardDocument75 pagesElegy Written in A Country ChurchyardKenneth Arvin Tabios100% (1)

- Elegy Written in A Country ChurchyardDocument4 pagesElegy Written in A Country ChurchyardM Munour RashidNo ratings yet

- The Poetical Works of Henry Kirk White : With a Memoir by Sir Harris NicolasFrom EverandThe Poetical Works of Henry Kirk White : With a Memoir by Sir Harris NicolasNo ratings yet

- Proserpine Midas T 00 Shel RichDocument132 pagesProserpine Midas T 00 Shel Richluluzoko gamesNo ratings yet

- The Poetry of Henry Kirke White: "Who shall contend with time, Unvanquished Time. The Conqueror of Conquerors and Lord of Desolation?"From EverandThe Poetry of Henry Kirke White: "Who shall contend with time, Unvanquished Time. The Conqueror of Conquerors and Lord of Desolation?"No ratings yet

- Milton's StyleDocument8 pagesMilton's StyleveershiNo ratings yet

- Jack Kolb, "Hallam, Tennyson, Homosexuality and The Critics"Document42 pagesJack Kolb, "Hallam, Tennyson, Homosexuality and The Critics"JonathanNo ratings yet

- Romantic BalladsDocument15 pagesRomantic Balladsvewaver810No ratings yet

- Lesson 7 William Shakespeare Who Is SylviaDocument34 pagesLesson 7 William Shakespeare Who Is Sylviahermogenes.margaretNo ratings yet

- Anthology of Contemporary PoetryDocument146 pagesAnthology of Contemporary Poetrycatalin_teodoriu83100% (1)

- Ballads of Mystery and Miracle and Fyttes of Mirth: Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - Second SeriesFrom EverandBallads of Mystery and Miracle and Fyttes of Mirth: Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - Second SeriesNo ratings yet

- The Holy Cross & Other Tales: "Books do actually consume air and exhale perfumes"From EverandThe Holy Cross & Other Tales: "Books do actually consume air and exhale perfumes"No ratings yet

- The Complete Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan PoeFrom EverandThe Complete Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan PoeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1736)

- The Poems of Emma Lazarus, Volume I: Narrative, Lyric, and DramaticFrom EverandThe Poems of Emma Lazarus, Volume I: Narrative, Lyric, and DramaticNo ratings yet

- Original sonnets on various subjects; and odes paraphrased from HoraceFrom EverandOriginal sonnets on various subjects; and odes paraphrased from HoraceNo ratings yet

- Elizabethan Sonnet-CyclesDelia - Diana by Constable, Henry, 1562-1613Document74 pagesElizabethan Sonnet-CyclesDelia - Diana by Constable, Henry, 1562-1613Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Full Text Is Here Thomas GrayDocument2 pagesThe Full Text Is Here Thomas GrayChandan V ChanduNo ratings yet

- Hearts of Controversy by Meynell, Alice Christiana Thompson, 1847-1922Document37 pagesHearts of Controversy by Meynell, Alice Christiana Thompson, 1847-1922Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Prose Fancies (Second Series) by Le Gallienne, Richard, 1866-1947Document62 pagesProse Fancies (Second Series) by Le Gallienne, Richard, 1866-1947Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Letters On Literature by Lang, Andrew, 1844-1912Document59 pagesLetters On Literature by Lang, Andrew, 1844-1912Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- From The Evaluation of Portraits Towards The Explication of PoemsDocument12 pagesFrom The Evaluation of Portraits Towards The Explication of PoemsSaleem NasimNo ratings yet

- Crosland-English Sonnet (1917)Document271 pagesCrosland-English Sonnet (1917)Trad Anon100% (1)

- An Elegy Wrote in A Country Church Yard (1751) and The Eton College Manuscript by Gray, Thomas, 1716-1771Document22 pagesAn Elegy Wrote in A Country Church Yard (1751) and The Eton College Manuscript by Gray, Thomas, 1716-1771Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

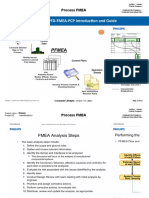

- CSR-05-074-15001 NDI D13 Dark Grey Sol Gel PFD-FMEA-PCP Rev 00Document54 pagesCSR-05-074-15001 NDI D13 Dark Grey Sol Gel PFD-FMEA-PCP Rev 00Wahyu Jumain HayarullahNo ratings yet

- Story MapDocument3 pagesStory MapChelleNo ratings yet

- Dot Day Handbook 2016 PDFDocument16 pagesDot Day Handbook 2016 PDFdanesenseiNo ratings yet

- Fire Effect On ConcreteDocument19 pagesFire Effect On ConcreteHesham MohamedNo ratings yet

- (Studies On Themes and Motifs in Literature 99) Virgulti, Ernesto - Boldt-Irons, Leslie Anne - Federici, Corrado - Disguise, Deception, Trompe-l'Oeil - Interdisciplinary Perspectives-Peter Lang (2009)Document331 pages(Studies On Themes and Motifs in Literature 99) Virgulti, Ernesto - Boldt-Irons, Leslie Anne - Federici, Corrado - Disguise, Deception, Trompe-l'Oeil - Interdisciplinary Perspectives-Peter Lang (2009)Priyank JainNo ratings yet

- FINALDocument88 pagesFINALJanki RajpuraNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Gnu Snowboard Uomo 2013/2014Document24 pagesCatalogo Gnu Snowboard Uomo 2013/2014Andrea PredoniNo ratings yet

- Guide To Rural England - Leicestershire & RutlandDocument48 pagesGuide To Rural England - Leicestershire & RutlandTravel PublishingNo ratings yet

- Stones of Venice (Introductions) by Ruskin, John, 1819-1900Document128 pagesStones of Venice (Introductions) by Ruskin, John, 1819-1900Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Building MaterialsDocument16 pagesBuilding MaterialsCleo Buendicho100% (1)

- Six-Year Evaluation of ThermalSprayed Coating of ZnAlDocument11 pagesSix-Year Evaluation of ThermalSprayed Coating of ZnAlPinto DamianNo ratings yet

- Report Archeolog 3-7-2018 yDocument40 pagesReport Archeolog 3-7-2018 yaamirazamNo ratings yet

- How To Make Crayons Fil ProjectDocument1 pageHow To Make Crayons Fil ProjectrobinsonNo ratings yet

- SummerWorks 2014 Festival Guide PDFDocument47 pagesSummerWorks 2014 Festival Guide PDFMichael CashNo ratings yet

- MarinaDocument28 pagesMarinaBryan Bab BacongolNo ratings yet

- Discrete and Decision MathematicsDocument1 pageDiscrete and Decision MathematicsshaniceNo ratings yet

- The HumanitiesDocument13 pagesThe HumanitiesLaziness OverloadNo ratings yet

- Iron Oxide Pigments For Producing Coloured Concrete PDSDocument2 pagesIron Oxide Pigments For Producing Coloured Concrete PDSLily ShubinaNo ratings yet

- Walkthrough Monster Hunter Portable 3rd 2167104Document3 pagesWalkthrough Monster Hunter Portable 3rd 2167104Pungkas Setia WibawaNo ratings yet

- Bmichael Events This Week 1 December 2010Document79 pagesBmichael Events This Week 1 December 2010Brandon AndrewsNo ratings yet

- Colour UpDocument3 pagesColour UpmanbgNo ratings yet

- The Decorated North Wall in The Tomb of PDFDocument83 pagesThe Decorated North Wall in The Tomb of PDFI Hernandez-FajardoNo ratings yet