Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sexual Difference Theory Rosi Braidotti A Companion To Feminist Philosophy Ed Jaggar and Young

Uploaded by

JuliaAbdallaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sexual Difference Theory Rosi Braidotti A Companion To Feminist Philosophy Ed Jaggar and Young

Uploaded by

JuliaAbdallaCopyright:

Available Formats

30.

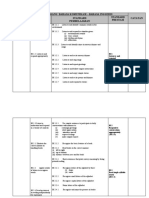

Sexual difference theory

ROSI BRAIDOTTI

Sections

Sexual difference as diagnostic map Sexual difference as political cartography Sexual difference as utopia

Sexual difference theory can best be explained with reference to French post-structuralism, more specifically its critique of the humanist vision of subjectivity. The post! in poststructuralism does not denote only a chronological brea" from the structuralists# generation of the $%&'s and $%('s, but also an epistemological and theoretical revision of the emancipatory programme of structuralism itself, especially of )arxist feminist political theory. The focus of poststructuralism is the complex and manifold structure of power and the diverse, fragmented, but highly effective ways in which power, "nowledge, and the constitution of subjectivity combine. *oststructuralism questions the usefulness of the notion of ideology,! especially in the sense developed by +ouis ,lthusser, as the imaginary relation of the Subject to his-her real conditions of existence. .n a feminist version, ideology refers to the patriarchal system of representation of gender and, more specifically, to the myths and images that construct femininity. Subjectivity is conceptuali/ed therefore as a process 0assujettissement1 which encompasses simultaneously the material 0 reality!1 and the symbolic 0 language!1 instances which structure it. *sychoanalytic notions of identity, language, and sexuality 2 especially in the wor" of 3acques +acan 2 play a central role in the redefinition of the subject as a process, rather than in the more traditional sense of a rational agent. The notion of difference emerges as a central concept in the poststructuralists# critique of both classical humanism and of the humanist legacy of )arxist-inspired structuralist social theory. .t includes both differences within each subject 0between conscious and unconscious processes1, as well as differences between the Subject and his-her 4thers. The ,merican reception of poststructuralist theories of difference, which 5omna Stanton 0$%6'1 described in terms of a transatlantic disconnection,! resulted in a series of polemical debates about the interrelation between the material and the symbolic reality and language, which tended to focus on the structure of power and the possibility of resistance to it. ,s 7li/abeth 8right argues 0$%%91, a

stalemate debate around essentialism! opposed French-oriented sexual difference theories to ,merican-based gender! theories throughout the $%6's. 8hereas gender! theorists understand the construction of masculinity and femininity as more determined by cultural and social processes, sexual difference theorists also understand it as determined by unconscious processes such as identification and internali/ation. , critical reevaluation of the whole debate was underta"en in the $%%'s, under the joint impact of postcolonial theories, the wor" of blac" women, women of color and of lesbian and queer theorists, as well as by an increasing diversification of positions within the 7uropean philosophies of sexual difference. .n order to avoid the polemic, while attempting to do justice to the complexity of the issues raised by sexual difference, . will concentrate on the wor" of +uce .rigaray because, as 8hitford argued 0$%%$1, she is the most prominent figure. . will distinguish between three different aspects of this theory: its analytic or diagnostic effect; its function as a political cartography; and the utopian aspect.

Sexual difference as diagnostic map

Sexual difference theory states the obvious but in so doing also radicali/es it. The main philosopher of sexual difference, +uce .rigaray, following on from Simone de <eauvoir#s analysis of the dialectics of the sexes, focuses at first on the difference between masculine and feminine subject positions =$%>&? 0$%6(a1. .rigaray relies on the theoretical toolbox of poststructuralism, however, especially on +acanian psychoanalysis, linguistics, and literary theory, to bring into focus the dissymetrical power relations that underlie the construction of woman as the 4ther of the dominant view of subjectivity. This dominant view is defined in terms of phallogocentrism. This term refers simultaneously to the fact that, in the 8est, thin"ing and being coincide in such a way as to ma"e consciousness coextensive with subjectivity: this is the logocentric trend. .t also refers, however, to the persistent habit that consists in referring to subjectivity as to all other "ey attributes of the thin"ing subject in terms of masculinity or abstract virility 0phallocentrism1. The sum of the two results is the unpronounceable but highly effective phallogocentrism. This notion involves for .rigaray both the description and the denunciation of the false universalism which is inherent in the phallogocentric posture: one which posits the masculine as a self-regulating rational agency and the feminine 4ther! as a site of devaluation. @oing beyond the Aegelian scheme, so prevalent in <eauvoir, .rigaray focuses on the perverse logic of this dualism. .t assumes that the phallogocentric system functions by constituting sets of pejorative 4thers,! or negative

instances of difference. .n such a system, difference! has historically been coloni/ed by power relations that reduce it to inferiority. Furthermore, it has resulted in passing off such differences as natural,! which then made entire categories of beings into devalued and therefore disposable entities. *ower, in this framewor", is the name given to a strategic set of close interrelations between multilocated positions: textual, social, economic, symbolic, and other sorts of positions. *ower, in other words, is another name for the political and social currency that is attributed to certain notions, concepts, or sets of meanings, in such a way as to invest them with either truth value! or with scientific legitimacy. To ta"e the example of misogyny and racism: the belief in the inferiority of women and people of color 2 be it mental, intellectual, spiritual, or moral 2 has no serious scientific foundation. This does not prevent it from having great currency in political practice and in the organi/ation of society. The corollary of this is that the woman or the person of color as 4ther! is different from! the expected norm: as such s-he is both the empirical referent for and the symbolic sign of pejoration. <ecause of this specific position, however, the devalued 4ther functions as a critical shaper of meaning. 5evalued or pejorative 4therness organi/es differences in a hierarchical scale that allows for the management and the governability of all gradations of social differences. <y extension, therefore, the pejorative use of difference is no accident, but rather it is structurally necessary to the phallogocentric system of meaning and the social order that sustains it. .t just so happens that the empirical subjects which are the referents for this symbolic pejoration experience in their embodied existence the effects of the disqualification. ,t this level, sexual difference is a powerful critique of philosophical dualism and of binary habits of thought. .n the same vein, it also challenges the categorical binary opposition of the symbolic to the empirical within psychoanalytic theory. The sexual difference approach, in other words, dislodges the belief in the natural! foundations of socially coded and enforced differences and of the system of values and representation which they support. )oreover, this approach emphasi/es the need to historici/e the very notions and concepts it analy/es, first and foremost among them the notion of difference. This emphasis on the historical embeddedness of concepts, however, also means that the thin"er needs some humility before the multilayered and complex structure of language. The implications of this analysis are far-reaching: phallogocentric logic is embedded in language, which is the fundamental political myth in our society. .n the poststructuralist framewor", language is not to be understood as a tool of communication, following the humanistic tradition. .t is rather defined as the site or location where subject positions are constructed. .n order to get access to language at all, however, one has to ta"e up a position on either side of the great masculine-feminine divide. The subject is sexed, or s-he is not at all.

,gainst the tendency of Freudian psychoanalysis to fix psychic structures through biological references, .rigaray and other sexual difference theorists problemati/e the question of the connection of morphological men and women to culturally coded roles of masculinity and femininity. )orphology replaces biological deterministic readings of the body with a psychosexual version of social constructivism. )orphologies refer to enfleshed, experiential understandings of the bodily self. ,s 7li/abeth @ros/ points out 0$%6%1, these experiences are mediated through discursive practices 0biological, psychological, psychoanalytic discourses1 which construct social representations. 7mbodied subjects are expected to adhere to these representations by internali/ing them. Thus, although language is posited as a structure that is prior to and constitutive of subjectivity, the sexed subject positions that structure identity 0)-F1 are neither stable nor essentialistic. , fundamental instability in the subject#s attachment to either masculine or feminine positions is proposed instead as the site of resistance to fixed or stable identities of any "ind. The subject is both sexed and split, both resting on one of the poles of the sexual dichotomy and unfastened to it. The linguistic turn! thus defined therefore provides sexual difference philosophy with a materially grounded historici/ed and yet ubiquitous structure on which to base its vision of subjectivity. .t is important to stress the political implications of this definition of language: the phallogocentric code being inscribed in language, it is operational no matter who happens to be spea"ing it. This emphasis on the in-depth structures or syntax of language implies that there is no readily accessible, uncontaminated, or authentic! voice of otherness, albeit among the oppressed. This turns into an attac" on the essentialism of any radical epistemological claim to authenticity. Blaims to epistemological or political purity are suspect because they assume subjectpositions that would be unmediated by language and representation. .rigaray radicali/es the psychoanalytic insight by showing, especially in her psycholinguistic studies, how morphology interacts with linguistic definitions in a very dynamic manner. )oreover, she focuses on female morphology as a privileged site of production of forms of resistance to the phallogocentric code. To conclude the diagnostic map, . would say that sexual difference provides a political anatomy of the in-depth structures of phallogocentrism, which is defined as intrinsically masculine, universalistically white, and compulsorily heterosexual. )oreover, it loc"s the feminine in a double bind: on the one hand it glorifies maternal powers to the detriment of the empowerment of female subjectivity, but on the other hand it stresses the fact that matricide is the foundation of the male psychosocial contract as well as femininity. *hallogocentrism is, in fact, the +aw of the Father and it confines the mother to symbolic insignificance. Feminist resistance to phallogocentrism consequently ta"es the form of a reappraisal of the maternal as a site of

empowerment of woman-centered genealogies. .rigaray claims these counter-genealogies as the start of an alternative female symbolic system.

Sexual difference as political cartography

The philosophy of sexual difference suggests that, because the specular relation between Subject and 4ther is dissymetrical, especially in terms of power relations between the sexes, there is no possible reversibility between their respective positions. )oreover, this dissymetry is proposed as the foundation for a new phase of feminist politics, especially in the .talian feminist reception of .rigaray#s wor" 0)ilan 8omen#s <oo"store Bollective $%%'1. The argument runs as follows: the fact that the two poles exist in a dissymetrical power relation toward each other also affects their respective relationship to otherness. .n the phallogocentric system, argues .rigaray, women#s otherness! in relation to each other remains unrepresentable because the peripheral other! is conceptuali/ed in function of and in relation to a masculine center. .rigaray refers to the former as the other of the 4ther! and to the latter as the 4ther of the Same.! Cnder the heading of the double syntax! .rigaray defends this irreducible and irreversible difference not only of 8oman from )an, but also of real-life women from the reified image of 8oman-as-4ther. Aence the feminist poststructuralist critique of <eauvoir#s emancipationims,! or equality-minded thought,! which is perceived as naive insofar as it assumes that women can simply grab! transcendence as a point of exit from the paradox of femininity as a systematically devalued site of otherness. .rigaray argues instead that the terms of the dialectical opposition are not reversible, either conceptually or politically. The theory of sexual difference rather ban"s on the politically subversive potential of the margins of excentricity that women enjoy from the phallogocentric system: it is women#s relative non-belonging! to the system that can provide margins of negotiation for alternative subject positions. 8hereas 3acques 5errida#s deconstructive philosophy is quite contented with confining the feminine to such margins of noncoincidence with the phallicsignifier, sexual difference feminists aim to use these margins to experiment with alternative forms of female empowerment. These margins, however, must be negotiated through careful processes of undoing hegemonic discourses at wor" not only in dominant culture, but also within feminist theory itself. Sexual difference as a strategy of empowerment thus is the means of achieving possible margins of affirmation by subjects who are conscious of and accountable for the paradox of being both caught inside a symbolic code and deeply opposed to it. This is why the feminist philosophy of difference

is careful in spea"ing of margins of nonbelonging to the phallic system. .n reverse, one could also spea" of areas of belonging by women to the same system they are trying to defeat. The point worth stressing is that, willingly or not, women are complicitous with that which they are trying to deconstruct. <eing aware of one#s implication or complicity lays the foundations for a radical politics of resistance which will be free of claims to purity but also of the luxury of guilt. Sexual difference theory thus stresses the positivity of difference, while opposing the automatic counter-affirmation of oppositional identities. Feminists need to revalue discourses and practices of difference, thus rescuing this notion from the hegemonic connotations it acquired in classical philosophical thin"ing. This reappraisal of difference is proposed as a political practice, which coincides with the critique of a humanistic understanding of subjectivity in terms of nationality, self-representation, homogeneity, and stability. This view of the subject is questioned in the light of its dualistic relation to otherness. )ore specifically, sexual difference theorists politici/e habits of metaphori/ation of the feminine as a figure of devalued difference. Thus, .rigaray pleads for a feminist reappropriation of the imaginary 2 that is to say of the images and representations that structure one#s relation to subjectivity. +anguage thus becomes a site of political resistance. . argued earlier that psychoanalytic theory plays an important role in theori/ing the fractured vision of the subject. 4ne of the lasting lessons of psychoanalysis is the insight that the notion of 8oman! refers to a female sex being morphologically constituted and sociali/ed so as to conform to the institution of femininity. .n "eeping with Foucault#s understanding of embodied subjectivity, femininity is understood as both a monument and a document. .t is both a set of social conventions and a set of social, legal, medical, and other discourses about a normal, standardi/ed female type. .n opposition to essentialistic and biologically or psychically deterministic accounts of femininity, psychoanalysis suggests that one is constituted as a woman through a series of mostly unconscious identifications with feminine subject positions 0see ,rticle 9>, psychoanalytic feminism1. .n a more political reading of this idea, .rigaray suggests <eauvoir was not systematic enough when she asserted that one is not born, one becomes a woman!: this assertion must be extended to cover unconscious structures and forms of identifications which resist willful and conscious processes of political transformation. .rigaray#s emphasis on the in-depth structure aims at radicali/ing <eauvoir#s formula by extending it to unconscious identity formations. The vision of the subject that emerges from this is firmly anti-Bartesian in that it challenges the classical coincidence of subjectivity with consciousness. Feminist politics challenges the structure of representation and the social and political values attributed to 8oman as the 4ther of the patriarchal system, but also extends this challenge to the deep structures of each woman#s identity. The corollary of the above is crucial: it implies that the women who underta"e the feminist position

2 as part of the process aimed at empowering alternative forms of female subjectivity 2 are split subjects and not rational entities. 7ach woman is a multiplicity in herself: she is mar"ed by a set of differences within the self, which turns her into a split, fractured, "notted entity, constructed over intersecting levels of experience. .rigaray, as most psychoanalytic feminists, focuses especially on the discrepancy between unconscious desires and willful choices. This deeply anti-Bartesian vision of the subject is not gratuitous, but it rather aims at providing a more adequate and consequently politically more effective mapping of the complexities that surround female agency. .t complexifies and updates an important question: why do not all women desire or long for freedom and autonomyD 8hy do they not desire to be freeD The feminist subject, in other words, is not a purely volitional or self-representational unit: she is also the subject of her unconscious and, as such, she entertains a set of mediated relationships to the very structures that condition her life-situations. There is no unmediated relation to gender, race, class, age, or sexual choice. .dentity is the name given to this set of potentially contradictory variables: it is multiple and fractured; it is relational in that it requires a bond to the others!; it is retrospective in that it functions through recollections and memories. +ast but not least, identity is made of successive identifications, that is to say of unconscious internali/ed images which escape rational control.

Sexual difference as utopia

The question then becomes: how to unfasten one#s attachment to and identification with certain images, forms of behavior and expectations that are constitutive of femininityD .n answering this question, sexual difference becomes a theory of female empowerment, based on a strategic use of repetition. .t is utopian as in a-topos, that is, it has no foundations as yet, it is nowhere! 2 but it does point to a process of significations that has already started. .rigaray calls mimesis! the strategy that consists in revisiting, reappraising and repossessing the female subject-position by women who have ta"en their distance from 8oman as a phallogocentric support-point. The starting point for the project of sexual difference is the political will to assert the specificity of the lived, female embodied experience. This amounts to the refusal to disembody sexual difference into an allegedly postmodern! subjectivity; while it reasserts the will to reconnect the poststructuralist project of deconstruction of fixed subjectivity to the social and political experience of embodied females. The philosophy of sexual difference argues that it is historically and politically urgent to bring about empowered notions of female subjectivity. Feminism is the strategy

of wor"ing through the sedimented layers of meanings and significations surrounding the notion of 8oman, at the precise moment in its historicity when, because of the decline of classical humanism, this notion has lost its substantial unity. Thus, as a political and theoretical practice, feminism unveils and consumes the different representations of 8oman in such a way as to open up spaces for alternative representations of women within this previously fixed essence which has been challenged by postmodernity. *ostmodernity has made femininity available to feminists as that which needs to be deconstructed and wor"ed upon. )imesis as the politics of as if! is a careful use of repetitions which confirms women in a paradoxical relation to femininity, but also enhances the subversive value of the paradoxical distance that women entertain from the same femininity. The political gamble is clear and the sta"es are high: for sexual difference theorists, the new is created by revisiting and burning up the old. The quest for alternative representations of female subjectivity requires the mimetic repetition and the reabsorption of the established forms of representation for the post-8oman women. The signifier woman cannot be relinquished by sheer volition: it must be consumed and reappraised from within. ,s . suggested briefly before, an important element of the mimetic repetition is, for .rigaray, the sense of women#s genealogies, which . read as a politically activated counter-memory. , feminist is someone who thin"s through her experience as a woman and through shared experience with other women. , feminist is someone who forgot to forget her bond to other women: a bond that is made not only of a shared oppression, but also of commonly experienced joys and ways of "nowing. . refer to this subject-position as the female feminist.! @enealogies constitute a symbolic legacy of female embodied and embedded experience, the starting point for which is the enfleshed location of the body. Eemembering that the enfleshed or embodied self is, for .rigaray, a de-essentiali/ed entity, which she reads with psychoanalytic insight, the bodily self can best be described as the intersection of many fields of experience and of social forces. .n a phallogocentric system, women are sociali/ed into thin"ing through a masculine symbolic structure which is sustained by an imaginary that reduces them to the 4ther of the Same.! Female feminist genealogies as counter-memories are a way of brea"ing through the mighty power of the phallic signifier and opening up spaces for women to redefine collectively their singular experiences as 4ther of the others.! Sexual difference is not to be understood, therefore, as an unproblematic category, nor is it to be radically separated from the wor"ings of other categories, such as class, race, ethnicity, and other coded social differences. .t does continue to privilege, however, sexed identity 2 the fact of being embodied female 2 as the primary site of resistance. This site is defined as a process of constitution of multiple, complex, and potentially contradictory facets or subject-position, as Teresa de +auretis suggests 0$%6>b1.

4ne of the most interesting new perspectives is offered by the intersection of sexual difference theory with other differences. The French school of sexual difference has come under criticism for its color-blindness and its disregard of race and ethnicity issues. Following <utler and Scott 0$%%91 the question can be reformulated in terms of the points of convergence between poststructuralist critiques of identity, and recent theories by women of color and of blac" feminists to expose the whiteness of feminist theory. .n postmodernity, what is needed are new transversal or intersectional alliances between postcolonialism, poststructuralism and post-gender theories 0Trinh T. )inh-ha $%6%, Spiva" $%6>b1. This would correspond to new interdisciplinary dialogues between philosophy and fields such as legal studies, critical studies and film theory, social and political thought, and economics and linguistics. The common running thread could be: which accountability is available to feminists wor"ing outside the reference to a universal, coherent, and stable self and yet still committed to agency, the empowerment of women and to theoretical and methodological accuracyD ,nother important new area of study is the relation between philosophical style and political agency. Sexual difference as a highly distinctive mode of philosophical thought has brought a new style into feminist philosophy: in a radical redefinition of interdisciplinarity, sexual difference thin"ers open the discipline of philosophy up to dialogical exchanges with all sorts of other 0nonphilosophical1 discourses. )oreover, the utopian dimension of sexual difference inaugurates a visionary mode of thin"ing where the poetic and the political intersect powerfully. )oreover, the anti-Bartesian vision of subjectivity which is implicit in sexual difference philosophy has the advantage of allowing for a political reading of affectivity. Thus, feminism gets redefined as the passion of sexual difference, that is to say as an object of desire for women who no longer recogni/e themselves in the phallogocentric 4ther of the Same,! that is, 8oman. , female feminist could thus be seen as someone who longs for and tends toward the empowerment of other representations of being-a-woman. The feminist project is no longer described only in terms of willful choice, but also in terms of desire, that is to say un-willful drives. Bonsequently political passions, and the political analysis of affectivity that accompanies them, emerge as a central issue. This also requires a critical reappraisal of the notion of desire itself. .rigaray, not unli"e 5eleu/e, challenges the equation between desire and negativity or lac", which also constitutes a Aegelian legacy in +acanian psychoanalysis, and proposes instead desire as the positive affirmation of one#s longing for plenitude and well-being 2 a form of felicity, or happiness. 8hat the feminism of sexual difference wants to free in women is thus also their desire for freedom, justice, selfaccomplishment, and well-being: the subversive laughter of 5ionysus as opposed to the seriousness of the ,pollonian spirit. This political process is forward-loo"ing, not nostalgic: it does not aim at

the glorification of the feminine, but rather at its actuali/ation or empowerment as a political project aimed at alternative female subjectivities. .t aims to bring into representation that which phallogocentrism had declared unrepresentable and thus to do justice to the sort of women feminists, in their great diversity, have already become.

ite this article

<E,.54TT., E4S.. FSexual difference theory.F A Companion to Feminist Philosophy. 3,@@,E, ,+.S4G ). and .E.S ),E.4G H4CG@ 0eds1. <lac"well *ublishing, $%%%.

Bi!liographic Details A ompanion to "eminist #hilosophy

$dited !y% ,+.S4G ). 3,@@,E and .E.S ),E.4G H4CG@ eISB&% %>6'IJ$99'I>$ #rint pu!lication date% $%%%

You might also like

- Gender or Sexual Identity TheoriesDocument5 pagesGender or Sexual Identity TheoriesJV Bryan Singson Idol (Jamchanat Kuatraniyasakul)No ratings yet

- Conflict TheoriesDocument2 pagesConflict TheoriesImman BenitoNo ratings yet

- Harrison-Ontologies of Gender and LoveDocument23 pagesHarrison-Ontologies of Gender and LoveWalterNo ratings yet

- Komarovsky 1950Document10 pagesKomarovsky 1950jmolina1No ratings yet

- Gender Definition ScottDocument2 pagesGender Definition Scottzhane2014fischerNo ratings yet

- The Interpretation of Cultures - Clifford Geertz ExportDocument4 pagesThe Interpretation of Cultures - Clifford Geertz ExportLautaro AvalosNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument26 pagesThe University of Chicago PressPedro DavoglioNo ratings yet

- Towards Tri-Hierarchization: Foucault's Tool for Analyzing Power HierarchiesDocument14 pagesTowards Tri-Hierarchization: Foucault's Tool for Analyzing Power HierarchiesJanmejay SinghNo ratings yet

- Social Work Queer Theory and After A GenDocument28 pagesSocial Work Queer Theory and After A Gennaufrago18No ratings yet

- Psychoanalysis and The Image: Introduction.Document12 pagesPsychoanalysis and The Image: Introduction.DenisseGonzález100% (1)

- Dietz - Current Controversies in Feminist TheoryDocument35 pagesDietz - Current Controversies in Feminist TheoryEstefanía Vela BarbaNo ratings yet

- Across Gender Across SexualityDocument12 pagesAcross Gender Across SexualityRuqiyya Qayyum100% (1)

- Biopolitics of SoulsDocument25 pagesBiopolitics of SoulsJavier RojasNo ratings yet

- Analytic FeminismDocument36 pagesAnalytic FeminismPablo BlackNo ratings yet

- Semiotics of Public and PrivateDocument19 pagesSemiotics of Public and PrivateArturo DíazNo ratings yet

- Phil 112 Exam NotesDocument4 pagesPhil 112 Exam NotesPhiwe MajokaneNo ratings yet

- Harre 1986 ReviewDocument5 pagesHarre 1986 ReviewaldogiovanniNo ratings yet

- IdeologiesDocument17 pagesIdeologiesmaleskunNo ratings yet

- Sex, Race, and Biopower: A Foucauldian AnalysisDocument26 pagesSex, Race, and Biopower: A Foucauldian AnalysisFernando UrreaNo ratings yet

- A Shubhra Ranjan PSIR Mains Test 5 2020Document10 pagesA Shubhra Ranjan PSIR Mains Test 5 2020Anita SharmaNo ratings yet

- Relations Philosophy: Some AnthropologyDocument12 pagesRelations Philosophy: Some AnthropologyMichaelBrandonScott_No ratings yet

- 24 Ethnic-Groups-And-Boundaries, Barth-IntroductionDocument3 pages24 Ethnic-Groups-And-Boundaries, Barth-IntroductionpaghundaummiaimanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Critical Discourse AnalysisDocument20 pagesIntroduction To Critical Discourse AnalysisMehrul BalochNo ratings yet

- Language and Sexuality: Chapter 20Document20 pagesLanguage and Sexuality: Chapter 20DannielCarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Queer Postcolonialism - AppuntiDocument4 pagesQueer Postcolonialism - AppuntibesciamellaNo ratings yet

- Coreografías Del Género - Susan L FosterDocument34 pagesCoreografías Del Género - Susan L FosterJuli SorterNo ratings yet

- Feminist Standpoint Theory - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyDocument17 pagesFeminist Standpoint Theory - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophySESNo ratings yet

- Epstein, S. (1994) 'A Queer Encounter - Sociology and The Study of Sexuality'Document16 pagesEpstein, S. (1994) 'A Queer Encounter - Sociology and The Study of Sexuality'_Verstehen_No ratings yet

- Adams 1998 Feminist theory discursiveDocument16 pagesAdams 1998 Feminist theory discursiveGabriela MagistrisNo ratings yet

- Sex and SocietyDocument16 pagesSex and SocietySimeon Tigrao CokerNo ratings yet

- Choreographing GenderDocument34 pagesChoreographing GenderC Rosa Guarani-KaiowáNo ratings yet

- Important Terms/Concepts in Feminist Theories: SubjectDocument15 pagesImportant Terms/Concepts in Feminist Theories: SubjectNitika SinglaNo ratings yet

- Conceptualization of IdeologyDocument9 pagesConceptualization of IdeologyHeythem Fraj100% (1)

- Elizabeth Povinelli - The Empire of Love. Introducción y Cap 2Document57 pagesElizabeth Povinelli - The Empire of Love. Introducción y Cap 2Rafael Alarcón VidalNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalysis and The Postcolonial Genealogy of Queer Theory D A - KDocument4 pagesPsychoanalysis and The Postcolonial Genealogy of Queer Theory D A - Kd alkassimNo ratings yet

- Sensing Disability - CorkerDocument20 pagesSensing Disability - CorkermanolisdegNo ratings yet

- Ferguson - Aberrations in Black. Toward A Queer of Color CritiqueDocument8 pagesFerguson - Aberrations in Black. Toward A Queer of Color CritiqueVCLNo ratings yet

- Project Muse 491557Document28 pagesProject Muse 491557tunishacoereciusNo ratings yet

- Lilli Zeuner - Review Essay Margaret Archer On Structural and Cultural Morphogenesis - NotesDocument4 pagesLilli Zeuner - Review Essay Margaret Archer On Structural and Cultural Morphogenesis - NotesKlara Benda100% (1)

- Choreographies of Gender-1Document34 pagesChoreographies of Gender-1cristinart100% (1)

- Public Sphere and Private Sphere - Masculinity and Femininity-LibreDocument11 pagesPublic Sphere and Private Sphere - Masculinity and Femininity-LibreGüzel Marmara100% (1)

- Grosz - The Labors of Love. Analyzing Perverse Desire - An Interrogation of Teresa de LDocument22 pagesGrosz - The Labors of Love. Analyzing Perverse Desire - An Interrogation of Teresa de Lseyda.ozturk9367No ratings yet

- Forming, As Opposed To Forcing, Causes, The Interpretive Epistemic Mode Can Offer ADocument8 pagesForming, As Opposed To Forcing, Causes, The Interpretive Epistemic Mode Can Offer AFatma WatiNo ratings yet

- The Grip of Ideology: A Lacanian Approach To The Theory of IdeologyDocument24 pagesThe Grip of Ideology: A Lacanian Approach To The Theory of IdeologyjohnnynottoscaleNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory Markus ThielDocument6 pagesQueer Theory Markus ThielJudea Warri AlviorNo ratings yet

- Narratives of the Self - How Stories Shape our IdentitiesDocument13 pagesNarratives of the Self - How Stories Shape our IdentitiesAlejandro Hugo GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Rules Define and Distinguish Human KinshipDocument30 pagesRules Define and Distinguish Human KinshipIlze LukstiņaNo ratings yet

- WWW Iep Utm EduDocument10 pagesWWW Iep Utm EduWawan WibisonoNo ratings yet

- The Unmet Needs That Will Drive at the Progress of Civilizing The Scientific Method Applied to the Human Condition Book I: II EditionFrom EverandThe Unmet Needs That Will Drive at the Progress of Civilizing The Scientific Method Applied to the Human Condition Book I: II EditionNo ratings yet

- Form Matter Chora Object Oriented OntoloDocument31 pagesForm Matter Chora Object Oriented OntoloHans100% (1)

- Gender and Culture Best and WilliamsDocument32 pagesGender and Culture Best and Williamscbujuri100% (6)

- Anotaciones de GUimaraesDocument4 pagesAnotaciones de GUimaraesDaniel AvilaNo ratings yet

- Sociology ManifestoDocument20 pagesSociology ManifestoAli TayefiNo ratings yet

- Anthier 1998 SReview n46 v3.Document32 pagesAnthier 1998 SReview n46 v3.kvcostaNo ratings yet

- Politics of IgnoranceDocument14 pagesPolitics of IgnoranceEduardo RestrepoNo ratings yet

- Chia Ling WangDocument12 pagesChia Ling WangkcwbsgNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 FeminismDocument20 pagesChapter 6 FeminismatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- The Question of Ideology - Althusser, Pecheux and Foucault PDFDocument22 pagesThe Question of Ideology - Althusser, Pecheux and Foucault PDFEser Kömürcü100% (1)

- Bhikhu Parekh Rethinking MulticulturalismDocument8 pagesBhikhu Parekh Rethinking MulticulturalismRedouane Amezoirou100% (1)

- ALCORN 2014 Community Forestry Latin America Lessons For REDD+Document74 pagesALCORN 2014 Community Forestry Latin America Lessons For REDD+BarbaraBartlNo ratings yet

- AyoColi - Unclothing African WomenDocument16 pagesAyoColi - Unclothing African WomenJuliaAbdallaNo ratings yet

- Adrienne Davis - Slavery and The Roots of Sexual Harassment 2003Document22 pagesAdrienne Davis - Slavery and The Roots of Sexual Harassment 2003JuliaAbdallaNo ratings yet

- IELTS Practise Materials Academic Test PDFDocument59 pagesIELTS Practise Materials Academic Test PDFHimanshu Baria0% (2)

- Basic Income Dilemmas - Van ParjsDocument4 pagesBasic Income Dilemmas - Van ParjsJuliaAbdallaNo ratings yet

- Seyla Benhabib - Strange Multiplicities - The Politics of Identity and DifferenceDocument31 pagesSeyla Benhabib - Strange Multiplicities - The Politics of Identity and DifferenceJuliaAbdalla100% (1)

- Arndt, Perspectives On African FeminismDocument15 pagesArndt, Perspectives On African FeminismJuliaAbdallaNo ratings yet

- Basic IncomeDocument5 pagesBasic IncomeJuliaAbdallaNo ratings yet

- Justice, Governance, CosmopolitanismDocument152 pagesJustice, Governance, CosmopolitanismIban MiusikNo ratings yet

- Schmitter Still The Century of IsmDocument48 pagesSchmitter Still The Century of IsmJuliaAbdallaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Guide V Writing TestDocument10 pagesTutorial Guide V Writing TestRithuik YerrabroluNo ratings yet

- Tugas Narrative TextDocument2 pagesTugas Narrative TextmikailadityapratamaNo ratings yet

- Differentiating Instruction For English Language Learners: By: Rebecca Brown, Shatoya Jones, Gary WolfeDocument20 pagesDifferentiating Instruction For English Language Learners: By: Rebecca Brown, Shatoya Jones, Gary WolfeDanilo G. BaradilloNo ratings yet

- Class-IV-week9-Class - IV - Week 1 PDFDocument20 pagesClass-IV-week9-Class - IV - Week 1 PDFHajra UbaidNo ratings yet

- English III & IV - 1stgr - WK8Document16 pagesEnglish III & IV - 1stgr - WK8dhondendanNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic TestDocument3 pagesDiagnostic TestAlex GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Tema 68Document10 pagesTema 68Ana BelénNo ratings yet

- The Simple GiftDocument8 pagesThe Simple GiftMe100% (1)

- Bridging Between LanguagesDocument14 pagesBridging Between Languagestrisha abadNo ratings yet

- 11 Ci SinifDocument9 pages11 Ci SinifXayala MuradovaNo ratings yet

- Negotiating Meaning between English and Spanish Speakers via Communication StrategiesDocument36 pagesNegotiating Meaning between English and Spanish Speakers via Communication StrategiesMarian CoriaNo ratings yet

- Compiler Construction: Parsing: Mandar MitraDocument33 pagesCompiler Construction: Parsing: Mandar MitraArwa KhalloufNo ratings yet

- Oral Communication LPDocument6 pagesOral Communication LPKyleNo ratings yet

- LessonsDocument10 pagesLessonsRamzel Renz Loto100% (2)

- Bulan Tunjang Bahasa Komunikasi - Bahasa Inggeris Catatan Standard Kandungan Standard Pembelajaran Standard Prestasi MAC AprilDocument8 pagesBulan Tunjang Bahasa Komunikasi - Bahasa Inggeris Catatan Standard Kandungan Standard Pembelajaran Standard Prestasi MAC Aprilmohd shubryNo ratings yet

- Using children stories to enhance readingDocument9 pagesUsing children stories to enhance readingAnh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Test Teach Test UpdatedDocument5 pagesTest Teach Test UpdatedHoda RadiNo ratings yet

- Versant Writing Test.: of PearsonDocument10 pagesVersant Writing Test.: of PearsonHarold Bonilla PerezNo ratings yet

- Writing-Argumentative Day 1 2Document7 pagesWriting-Argumentative Day 1 2api-345483624No ratings yet

- Unit - I Poetry 1.the Bird Sanctuary-Sarojini NaiduDocument3 pagesUnit - I Poetry 1.the Bird Sanctuary-Sarojini Naiduqueensmiling495No ratings yet

- ESP Reading Programs in IndonesiaDocument13 pagesESP Reading Programs in IndonesiaDiah Retno WidowatiNo ratings yet

- Differences Between Animal and Human CommunicationDocument2 pagesDifferences Between Animal and Human CommunicationMaryam Raza100% (1)

- ESL Lesson 2 - Handout - Basic A1 - Occupations (Handout)Document4 pagesESL Lesson 2 - Handout - Basic A1 - Occupations (Handout)BarbaraNo ratings yet

- Communication Theory 2 Cop206xDocument10 pagesCommunication Theory 2 Cop206xThandeka KhwelaNo ratings yet

- Selected MCQsof LinguisticsDocument45 pagesSelected MCQsof LinguisticsDanish BhattiNo ratings yet

- Varieties and Registers of Spoken and Written EnglishDocument41 pagesVarieties and Registers of Spoken and Written EnglishMJ Murilla100% (2)

- Uses of TensesDocument7 pagesUses of TensesJagadishBabu ParriNo ratings yet

- tHE CONCEPT OF NEOLOGISMSDocument4 pagestHE CONCEPT OF NEOLOGISMSjanaNo ratings yet

- Intermediate - Grammar in UseDocument2 pagesIntermediate - Grammar in UseАрина Епифанова0% (1)

- Ejercicio Interactivo de Present Simple TenseDocument4 pagesEjercicio Interactivo de Present Simple TenseIrley FernandezNo ratings yet