Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jakki Mohr Robert Spekman - Characteristics of Partnership Success - Partnership Attributes, Communication Behavior, and Conflict Res

Uploaded by

Fahim JavedOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jakki Mohr Robert Spekman - Characteristics of Partnership Success - Partnership Attributes, Communication Behavior, and Conflict Res

Uploaded by

Fahim JavedCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategic Management Journal, Vol.

15, 135-152 (I 994)

I\

CHARACTERISTICS OF PARTNERSHIP SUCCESS: PARTNERSHIP ATTRIBUTES, COMMUNICATION BEHAVIOR, AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION TECHNIQUES

JAKKI MOHR

College of Business and Administration, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, U.S.A.

ROBERT SPEKMAN

T-

Darden Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A.

The formation of partnerships between firms is becoming an increasingly common way for firms to find and maintain competitive advantage. While the antecedents of partnership formation and the characteristics of the resulting cooperative working relationship have been explored in the literature, an understanding of characteristicsassociated with partnership s lacking. Such an understanding is important in reconciling the prescriptions to success i form partnerships with the reality that a majority of such partnerships do not succeed. W e hypothesize that partnership attributes, communication behavior, and conflict resolution techniques are related to indicators of partnership success (satisfaction and sales volume in the relationship). The hypotheses are tested with vertical partnerships between manufacturers and dealers. Results indicate that the primary characteristics of partnership success are: partnership attributes of commitment, coordination, and trust; communication quality and participation; and the conflict resolution technique of joint problem solving. The findings offer insight into how to better manage these relationships to ensure success.

PURPOSE

To begin, partnerships are defined as purposive strategic relationships between independent firms who share compatible goals, strive for mutual benefit, and acknowledge a high level of mutual interdependence. They join efforts to achieve goals that each firm, acting alone, could not attain easily. The formation of these alliances and partnerships is motivated primarily to gain competitive advantage in the marketplace (Bleeke

Key words: Strategic partnership, success, communication

and Ernst, 1991; Powell, 1990). Partnerships can afford a firm access to new technologies or markets; the ability to provide a wider range of products/services; economies of scale in joint research and/or production; access to knowledge beyond the firm's boundaries; sharing of risks; and access to complementary skills (Powell, 1987: 71). However, prescriptions for the formation of such partnerships often overlook the drawbacks/ hazards of such relationships. For example, increasing complexity, loss of autonomy and information asymmetry (Provan, 1984; Williamson, 1975) may accompany partnering relationships. Although the number of attempted partnerships

Received 31 July 1991 Final revision received 2 June 1993

CCC 0143-2095/94/020135-18

01994 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

136

1 . Mohr and R . Spekman

has grown almost geometrically in recent years, the rates of success are rather low (Harrigan, 1988; Kanter, 1988; Levine and Byrne, 1986). In fact, while the formation of partnering relationships is often viewed as a panacea for an individual firms competitive woes, the prescription to form an alliance to gain competitive advantage overlooks the fact that many strategic partnerships do not succeed. Unfortunately, the academic literature has been slow to embrace this important managerial concern (i.e., Day and Klein, 1987), and little guidance has emerged on how to better ensure partnership success. Knowledge of factors that are associated with partnership success could aid in the selection of partners as well as in the on-going management of the partnership. The purpose of this paper, then, is to address the characteristics of partnerships that are associated with its success. First, we provide a brief overview of the literature on strategic alliances. Then, we build a model of partnership success. We empirically test our model in the context of vertical partnerships in the computer industry. Finally, conclusions for managers and researchers are discussed.

might be viewed as a function of continuation (e.g., Harrigan, 1988), relationship longevity (vs. dissolution) may not accurately capture partnership success-some partnerships are purposively dissolved after a period of time (Hamel, Doz, and Prahalad, 1989). In our model we use two indicators of partnership success: an objective indicator (sales volume flowing between dyadic partners) and an affective measure (satisfaction of one party with the other). The objective indicator grows from the belief that strategic partnerships are formed to achieve a set of goals (e.g., to enhance a companys competitive position). The attainment of such goals can provide one indicator of relationship success. For example, in a partnership between firms in a distribution channel (e.g., Johnston and Lawrence, 1988; Narus and Anderson, 1987), manufacturers form partnerships with downstream channel members for a variety of reasons, including the ability to increase local market penetration. Manufacturers working in concert with these channel partners are able to provide better service to customers, thereby increasing their sales base in a particular geographic region. The affective indicator (satisfaction) is based on the notion that success is determined, in part, by how well the partnership achieves the LITERATURE REVIEW performance expectations set by the partners Research on strategic alliances has posited (e.g., Anderson and Narus, 1990). A partnership theories addressing the reasons why firms enter which generates satisfaction exists when performinto closer business relationships. For example, ance expectations have been achieved. transactions costs analysis (Williamson, 1975, 1985), competitive strategy (i.e., Porter, 1980), resource dependence (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK Thompson, 1967), political economy (Benson, 1975; Stern and Reve, 1980), and social exchange Our framework is based upon the following two theory (e.g., Anderson and Narus, 1984) each premises. First, partnerships tend to exhibit make predictions about when partnerships will behavioral characteristics that distinguish these be formed. Implicit in this research is the more intimate relationships from more traditional assumption that, when used under the appropriate (conventional) business relationships (Borys and circumstances and environmental conditions, Jemison, 1989). Second, while partnerships in partnerships will be successful. Yet, as mentioned general tend to exhibit these behavioral characterpreviously, a large percentage of these strategic istics, more successful partnerships will exhibit partnerships do not succeed (e.g., Harrigan, 1985, 1988). Given this inconsistency, one must I We recognize that these two indicators of partnership question what factors are associated with partner- success, while being applicable to many partnerships, may not to all oartnershbs. As discussed subseouentlv be aDDhcable shiD success. .. . , in the Methods section, these two indicators are contextDeveloping a model of partnership dependent, tailored for the specific empirical context for this begs the question Of what partnership studv-vertical DartnershiDs between manufacturers and means. Although success in strategic partnerships dealers.

Characteristics of Partnership Success

137

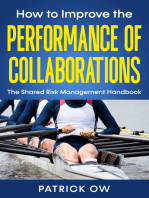

these characteristics with more intensity than less flow of information between partners, manage the depth and breadth of interaction, and capture successful partnerships. These behavioral characteristics might include the complex and dynamic interchange between attributes of the partnership, such as commitment partners. Extant literature has focused on commitand trust (e.g., Salmond and Spekman, 1986); ment, coordination, interdependence and trust communication behaviors, such as information as important attributes of partnerships (e.g., sharing between the partners (e.g., Mohr and Anderson and Narus, 1990; Day and Klein, 1987; Nevin, 1990); and conflict resolution techniques, Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh, 1987; Frazier, Spekman, which tend towards joint problem solving, rather and ONeal, 1988; Salmond and Spekman, 1986). than domination or ignoring the problems (e.g., The existence of these attributes implies that Borys and Jemison, 1989). Figure 1 serves as an both partners acknowledge their mutual depenorganizing framework for both the theoretical dence and their willingness to work for the discussion and the subsequent testing of hypoth- survival of the relationship. Should one party act opportunistically, the relationship will suffer and eses. both will feel the negative consequences.

Attributes of the partnership

Kanter (1988) suggests that strategic partnerships result in blurred boundaries between firms in which there emerge close ties that bind the two parties. John (1984) describes the long and sticky nature of the relationship between firms that serves to reduce the potential for opportunistic behavior. In such relationships there exists a set of process-related constructs that help guide the

Commitment

Commitment refers to the willingness of trading partners to exert effort on behalf of the relationship (Porter ec al., 1974). It suggests a future orientation in which partners attempt to build a relationship that can weather unanticipated problems. A high level of commitment provides the context in which both parties can achieve

Attributes of the Partnership Commitment - Coordination - Interdependence Trust

Communication Behavior Quality - Information Sharing - Participation

Success of Partnership - Satisfaction - Dyadic Sales

- Persuasion - Smoothing - Domination - HarshWords - Arbitration

-Joint Problem Solving

Figure 1. Factors associated with partnership success

138

J . Mohr and R . Spekman

suggest that once trust is established, firms learn that joint efforts will lead to outcomes that exceed what the firm would achieve had it acted solely in its own best interests. In sum, the literature cited above suggests that more successful partnerships are expected to be characterized by higher levels of commitment, coordination, interdependence and trust than are less successful partnerships. This can be stated more formally by the following hypothesis.

HI: More successful partnerships, compared with less successful partnerships, exhibit higher levels of: a. commitment b . coordination c. interdependence d . trust. Communication behavior

individual and joint goals without raising the specter of opportunistic behavior (e.g., Cummings, 1984). Because more committed partners will exert effort and balance short-term problems with long-term goal achievement, higher levels of commitment are expected to be associated with partnership success (Angle and Perry, 1981).

Coordination

Coordination is related to boundary definition and reflects the set of tasks each party expects the other to perform. Narus and Anderson (1987) suggest that successful working partnerships are marked by coordinated actions directed at mutual objectives that are consistent across organizations. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) suggest that stability in an uncertain environment can be achieved via greater coordination. Without high levels of coordination, Just-in-Time processes fail, production stops, and any planned mutual advantage cannot be achieved.

Interdependence

As firms join forces to achieve mutually beneficial goals, they acknowledge that each is dependent on the other. This perspective flows directly from an exchange paradigm (e.g., Cook, 1977). Interdependence results from a relationship in which both firms perceive mutual benefits from interacting (e.g., Levine and White, 1962) and in which any loss of autonomy will be equitably compensated through the expected gains (Cummings, 1984). Both parties recognize that the advantages of interdependence provide benefits greater than either could attain singly.

Trust

Because communication processes underlie most aspects of organizational functioning, communication behavior is critical to organizational success (Kapp and Barnett, 1983; Mohr and Nevin, 1990; Snyder and Morris, 1984). In order to achieve the benefits of collaboration, effective communications between partners are essential (Cummings, 1984). Communication captures the utility of the information exchanged and is deemed to be a key indicant of the partnerships vitality. Three aspects of communication behavior are discussed here: communication quality, extent of information sharing between partners, and participation in planning and goal setting.

Communication quality

Pruitt (1981) indicates that trust (i.e., the belief that a partys word is reliable and that a party will fulfill its obligation in an exchange) is highly related to firms desires to collaborate. Williamson (1985) states that, other things being equal, exchange relationships featuring trust will be able to manage greater stress and will display greater adaptability. Zand (1972) contends that the lack of trust will be deleterious to information exchange, to reciprocity of influence, and will diminish the effectiveness of joint problem solving. Anderson and Narus (1990) add credence to the above and

Communication quality is a key aspect of information transmission (Jablin et al., 1987). Quality includes such aspects as the accuracy, timeliness, adequacy, and credibility of information exchanged (Daft and Lengel, 1986; Huber and Daft, 1987; Stohl and Redding, 1987). Across the range of potential partnerships, communication quality is a key factor of success. Timely, accurate, and relevant information is essential if the goals of the partnership are to be achieved. MacNeil(l981) and others acknowledge the importance of honest and open lines of communication to the continued growth of close ties between trading partners.

Characteristics of Partnership Success Information sharing

139

Information sharing refers to the extent to which critical, often proprietary, information is communicated to ones partner. Huber and Daft (1987) report that closer ties result in more frequent and more relevant information exchanges between high performing partners. By sharing information and by being knowledgeable about each others business, partners are able to act independently in maintaining the relationship over time. The systematic availability of information allows people to complete tasks more effectively (Guetzkow, 1965), is associated with increased levels of satisfaction (Schuler, 1979), and is an important predictor of partnership success (Devlin and Bleackley, 1988).

Participation

Participation refers to the extent to which partners engage jointly in planning and goal setting. When one partners actions influence the ability of the other to effectively compete, the need for participation in specifying roles, responsibilities, and expectations increases. Anderson, Lodish and Weitz (1987) and Dwyer and Oh (1988) suggest that input to decisions and goal formulation are important aspects of participation that help partnerships succeed. Driscoll (1978) also found that participation in decision-making is associated with satisfaction. Joint planning allows mutual expectations to be established and cooperative efforts to be specified. In sum, more successful partnerships are expected to exhibit higher levels of communication quality, more information sharing between partners, and more participation in planning and goal setting than less successful partnerships. Stated more formally, we hypothesize that: H2: More successful partnerships, compared with less successful partnerships, will exhibit higher levels of: a. communication quality 6 . information sharing c. participation in planning. Conflict resolution techniques Conflict often exists in interorganizational relationships due to the inherent interdependen-

cies between parties. Given that a certain amount of conflict is expected, an understanding of how such conflict is resolved is important (Borys and Jemison, 1989). The impact of conflict resolution on the relationship can be productive or destructive (Assael, 1969; Deutsch, 1969). Thus, the manner in which partners resolve conflict has implications for partnership success. Firms in a strategic partnership are motivated to engage in joint problem solving since they are, by definition, linked in order to manage an environment that is more uncertain and/or turbulent than each alone can control (Cummings, 1984) and integrative outcomes satisfy more fully the needs and concerns of both parties (Thomas, 1976). When parties engage in joint problem solving, a mutually satisfactory solution may be reached, thereby enhancing partnership success. Partners often attempt to persuade each other to adopt particular solutions to the conflict situation. These persuasive attempts will generally be more constructive than the use of coercion or domination (Deutsch, 1969). The use of destructive conflict resolution techniques (e.g., domination, confrontation) are seen as counter-productive and are very likely to strain the fabric of the partnership. In some partnerships, the method of conflict resolution is institutionalized, and third party arbitration is sought. While such mediation can be helpful in producing beneficial outcomes (Anderson and Narus, 1990), internal resolution (i.e., not relying on outside parties) shows a greater promise of long-term success (Assael, 1969: 580). While outside arbitration may be effective for a particular conflict episode, ongoing use of arbitrators may indicate inherent problems in the relationship. Other conflict resolution techniques (e.g., smoothing over or ignorindavoiding the issue) are somewhat at odds with the norms and values espoused in more successful strategic partnerships (see Ruekert and Walker, 1987). Such techniques do not fit with the more proactive tone of a partnership in which problems of one party become problems affecting both parties. As a result, smoothing or avoiding fails to go to the root cause of the conflict and tends to undermine the partnerships goal of mutual gain. Thus, we hypothesize that: H3: More successful partnerships, compared with less successful partnerships, will exhibit:

140

J . Mohr and R. Spekman

efficiently. In addition, such dealer partnerships enabled manufacturers to retain some control over dealer strategies and provided more accurate and valuable street-level market knowledge. Although single-industry studies often lack generalizability, they do afford greater control over sources of extraneous variation due to industry characteristics, environmental noise, and the like (e.g., McDougall and Robinson, 1990; see also Spekman and Gronhaug, 1986). We have attempted to enhance the studys internal validity, with full recognition that it is achieved with some loss in its external validity (Cook and Campbell, 1979). The unit of analysis in this study was the relationship between a computer dealer and one of its suppliers (i.e., manufacturers). We focused on the dealers perceptions of the relationship with a referent manufacturer (described below). While dyadic data (collected from both the dealer and the manufacturers) would have been desirable, both time and expense considerations necessitated focusing on one side of the dyad. A list of computer dealers was obtained from the Association of Better Computer Dealers, the personal computer industry trade association. Each dealer was contacted by telephone prior to mailing a questionnaire in order to identify the ownerhanager (the key informant), to solicit cooperation for the study, and to assign a referent manufacturer. One informant from the dealer firm was deemed to be appropriate (see Anderson, 1985; Campbell, 1955) since the owner1 manager is typically the top decision maker within the dealer firm; has key contact with the manufacturer with respect to strategic decisions (as opposed to contact for technical support, etc.); and, is the focal point for these small businesses (average number of employees ranges from %34, Computer Reseller News, 1988). During the initial phone contact, dealers were randomly assigned a referent manufacturer about whom the questionnaire centered. This random assignment ensured that dealer respondents did not pick either their most or least favored (i.e., best or worst) manufacturer as the referent. Five hundred fifty-seven surveys were mailed, with follow-up letters 4 weeks later. A total of 140 dealers returned surveys (25% response rate). This response rate was lower than expected, and likely due to the lengthy nature of the questionnaire and the busy time of the year at

a. higher use of constructive resolution techniques, including joint problem solving and persuasion b. lower use of destructive conflict resolution techniques including domination and harsh words c. lower use of conflict resolution techniques including outside arbitration, and smoothing1 avoiding issues.

METHOD

Data collection: Context and sample

Although strategic partnerships can take many forms, including both horizontal and vertical relationships (Borys and Jemison, 1989), this study focused on vertical relationships between manufacturers and dealers (e.g., Anderson and Narus, 1990; Heide and John, 1990). While not all channel relationships are strategic partnerships, manufacturers and dealers often form bonds that transcend a more market-based set of transactions. These closer, more intimate, bonds are what separates these partnerships from a more transaction-based set of exchanges which are limited in scope and purpose. Partners have jointly aligned goals to accomplish mutually beneficial ends. They are linked in form and substance in ways that go beyond the more conventional flow of products and paper trail found in other manufacturer-retailer relationships. In fact, the trend towards partnerships in channels relationships appears to be quite pronounced (Johnston and Lawrence, 1988; Sethuraman, Anderson, and Narus, 1988). The context selected for this study was the personal computer industry. As the market has matured, manufacturers have relied less on direct sales and more on dealer networks to help reach the vast market of small business customers (Bertrand, 1989; Business Week, 1989).* These manufacturers found that dealers in local markets were able to develop tailored solutions for specific market applications and to undertake the selling job, both more effectively and

* In recent years, mail order channels (e.g., Dell) have taken

a portion of the PC market (Business Week, 1991). Nonetheless, retail channels still account for the majority of PC sales and even Dell has begun to distribute through retail channels.

Characteristics of Partnership Success which it was mailed (November-December). Nonetheless, the response rate is quite acceptable and is consistent with the rate found in other studies (cf. Pearce and Zahra, 1991; Weiss and Anderson, 1992). Sixteen surveys were eliminated from analysis due to incomplete responses, leaving a total of 124 surveys for analysis. An ideal assessment of nonresponse bias compares characteristics of respondents to characteristics of the population from which the sample was drawn, in this case, the trade association membership. However, this trade association did not keep detailed records on their membership. In fact, it lacked meaningful information on even basic data, such as dealer size and sales volume. Absent this comparison base, we assessed nonresponse bias by comparing early to late respondents, as suggested by Armstrong and Overton (1977). They argue that late respondents are more representative of those in the sample who did not respond than are early respondents. This comparison indicated no significant differences between early and late respondents on characteristics such as sales volume and length of relationship with the referent manufacturer. Early respondents were, however, slightly smaller than later respondents in terms of number of employees ( t = -2.36, p < 0.02) and total sales volume ( t = -1.68, p < 0.10). Based on these results, nonresponse bias did not appear to present a problem in testing our framework. Five of the dealers who responded to the survey indicated that they were owned by the manufacturer (i.e., Heath Zenith, Radio Shack). Because vertical integration is an alternative governance form to partnerships (Achrol, Scheer, and Stern, 1990; Harrigan, 1985) these five dealers were omitted from data analysis. Additionally, dealers who did not deal directly with the manufacturer (i .e., purchased from distributors) were also omitted from the data analysis (n = 17). The remaining sample (n = 102) was comprised of dealers with an average of 24 employees, and total monthly sales of $1.15 million. These dealers reported on relationships with the following vendors: IBM (n = 21), Apple (n = 21), Compaq (n = 14), Hewlett Packard (n = 7), Epson (n = 6), NEC (n = 5 ) , Hyundai (n = 4), with the remaining 24 dealers responding on 16 manufacturers. The average length of these trading relationships was 3.87 years. Measurement

141

All measures were pretested in a series of personal interviews with computer dealers in which the items were revised iteratively until no further changes were suggested. The Appendix lists items used to measure each of the constructs. Reliability analysis was conducted and items with low item-to-total correlations were deleted. Cronbachs alphas were computed, and all scales (with one exception, as noted) exceeded Nunnallys (1978) reliability guidelines of 0.7 or above. The one exception, Information Sharing, had a Chronbach alpha of 0.68, which was deemed acceptable to further analysis. Principal component factor analyses with varimax rotations also were conducted for the variables in each hyp~thesis.~ Through this process, measures retained for the analysis exhibit favorable reliability, as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Churchill, 1979). Table 1 lists summary scale statistics. Success of the partnership Because vertical partnerships in the computer industry are formed in order to gain competitive advantage by more effectively and efficiently selling product, dealer sales volume of the referent manufacturers product served as one indicator of partnership success. In a vertical partnership one would expect that closer ties between the manufacturer and the dealer would result in the dealer selling more of that particular manufacturers product. Two objective measures of sales volume were taken; one was a direct measure and one was indirectly computed from two other items. The first (direct) measure asked the dealer: What is your approximate volume of sales of thh manufacturers product, on a monthly basis? The second measure was computed based on the dealers response to two items: 0 What are the total monthly sales of your dealership? 0 Of the total sales of your dealership, what percent comes from this manufacturers product?

The factor analyses are available from the first author, upon request.

142

J. Mohr and R. Spekman

in two different ways, we would get a more accurate assessment of this variable. These sales measures were adjusted for the size of the dealer (in terms of the number of employees). This adjustment was necessary in order to remove dealer size as an alternative explanation for greater sales volume, and therefore, a more successful partnership. The two sales measures were transformed with a logarithmic transformation to account for the increasing size of the categories (e.g., Govindarajan, 1988) and summed to form one measure, Dyadic Sales (see Table l).4 An additional indicator of partnership success was also taken. Anderson and Narus (1990) suggested that satisfaction with aspects of the working relationship between partners can serve as a proxy for partnership success. Satisfaction/ dissatisfaction is a cognitive state and examines the adequacy of the rewards received through the relationship (e.g., Frazier, 1983). Hence, an additional indicator of success in this study examined one partners satisfaction with the other across several aspects of the relationship, ranging from the general nature of personal dealings, to the level of promotional support, to profitability (Ruekert and Churchill, 1984). The factor analysis for the satisfaction items resulted in a two-factor solution. One factor, comprised of the two items tapping satisfaction with profit and margins, was termed Satisfaction and Profit. The second factor, comprised of the remaining satisfaction items, was termed Satisfaction with Manufacturer Support . Table 1 shows the relevant scale statistics and reliability coefficients of these two scales.

For this second measure, the two items were multiplied together as an indirect measure of the dealers monthly sales volume of the referent manufacturers product. We felt that by assessing dyadic sales volume

Table 1. Summary statistics for measures Variable Dependent variables Dyadic sales Satisfaction with support from mftr Satisfaction with profit Independent variables H1: Trust Mean* (S.D.) Coefficient Alpha

8.13*** (2.13) 3.25 (0.81) 2.79 (1.01)

0.51** 0.80 0.63**

3.28 (0.85) Commitment 4.27 (0.84) 3.10 Coordination (0.86) 2.61 Interdependence (1.00) H2: Communication quality 3.52 (0.91) 2.53 Participation (0.97) 3.57 Information sharing (0.68) H3: Joint problem solving

Persuasion Smoothing Arbitration Severe resolution**** Covariate Closeness

0.75 0.81 0.68** 0.26** 0.91 0.84 0.68

NA NA NA NA

3.28 (0.98) 3.37 (0.83) 3.15 (0.91) 1.40 (0.79) 2.09 (1.05) 3.27 (0.77)

0.56**

Attributes of the partnership Commitment, coordination, and trust were each measured with 3-item scales. The Commitment and Trust scales exhibited acceptable reliabilities, as shown in Table 1. One of the coordination items had a low item-to-total correlation and was dropped from analysis; the remaining two items had an intercorrelation of r = 0.68 (p < 0.001). Interdependence was measured with a two item scale and examined the ease with which each

Note that the variable Dyadic Sales is a scale and the values that it takes do not (and are not meant to) represent actual sales volume.

0.83

* Means are scaled from 1-5, with 5 being highest. * * Correlation coefficient, rather than coefficient alpha, is reported for a 2-item scale. * * * Mean of sales (log) ranges from 3.92 to 13.69. See text in the Measurement Section for elaboration. **** Severe Resolution includes the average of Harsh Words + Manufacturer Domination. NA Because Conflict Resolution Techniques were measured using composite indicators, which are comprised of single items, no reliability analysis is conducted (e.g., Howell, 1987).

Characteristics of Partnership Success

party could switch to a new trading partner (Phillips, 1981). While the intercorrelation between these two items was relatively low ( r = 0.26, p < 0.001), one would not necessarily expect both dealer and manufacturer dependence on the other to covary. In fact, it is possible that one party may find it easy to switch, while the other does not (see Spekman and Salmond, 1992). In any case, as the sum of these two items increases, so too does interdependence in the relationship. All items exhibited high loadings on their respective factors, with only one item crossloading (one coordination item on trust); however, in order to avoid using single-item measures this item was retained. The impact of this decision on the discriminant validity of trust and coordination must be kept in mind in interpreting the results.

143

as a check list, or composite scale, in which each item taps a different dimension of the construct. Hence, traditional reliability analysis is not appropriate. Four of these items (joint problem solving, persuasive attempts by either party, smoothing over the problem, and arbitration) were treated as unitary items. The remaining two items (harsh words and manufacturer domination) exhibited a relatively high intercorrelation (r = 0.56, the highest intercorrelation of the conflict resolution modes, the next highest at r = 0.45), and in the interest of parsimony, were summed and labeled Severe Conflict Resolution. Again, each variable loaded cleanly on its own factor.

Covariate

In testing the hypotheses, it was important to rule out alternative explanations for the findings, or other causal factors of partnership success. It was particularly important to establish that the independent variables (detailed above) were actually predictors of the success of the partnership, and not merely characteristics of partnerships in general. In order to control for this possibility, an additional measure was taken for the degree of closeness in the relationship. Such an analysis allows for partialing out the effects of partnerships in general (i.e., that they are closer relationships and thus exhibit more of the characteristics posited here to be predictors of partnership success) before testing the hypotheses for predictors of partnership success. Varadarajan and Rajaratnam (1986) portray closeness as the proximity of the relationship as it pertains to joint programs and the ties that bind the working relationship between parties. Closeness, as operationalized here, reflects notions of joint action and shared norms and is consistent with work by Heide and John (1990) and MacNeil (1981). The four items comprising this scale loaded on one factor and had a coefficient alpha of 0.83. Multicollinearity Correlation matrices were computed for the variables tested in each of the hypotheses. Multicollinearity becomes a concern with high intercorrelations among the independent variables (Cohen and Cohen, 1983; Mason and

Aspects of communication behavior

Communication quality was assessed with a 5-item scale; participation was measured with a 4-item scale and tapped the extent to which the dealers input was solicited by the manufacturer for planning purposes. Both of these measures exhibited good reliability and clean factor loadings. Information sharing tapped the extent to which partners kept each other informed about important issues on a voluntary basis and was assessed with an 8-item scale. Two items were dropped during initial reliability assessment. In the initial factor analysis, the two items that assessed the manufacturers sharing of information with the dealer did not exhibit clean loadings and, in fact, loaded more strongly on the other two measures of communication behavior. Thus, these two items were dropped, and four items were retained for the dealers information sharing with the manufacturer (coefficient alpha = 0.68). The items for this measure loaded cleanly on one factor, and were retained in the analysis.

Conflict resolution

The measures for conflict resolution included six modes by which conflict could be resolved. These items were designed to cover a spectrum of conflict resolution modes as described previously. Howell (1987) refers to this type of mesaurement

144

J . Mohr and R. Spekman

Hypothesis 1

Perreault, 1991). For H1, only one pair-wise correlation was problematic, that between trust and coordination ( r = 0.56). The remaining correlations ranged from r = 0.04-0.37. For both H2 and H3, the pair-wise correlations among the independent variables ranged from r = 0.01-0.39. While these correlations indicate that multicollinearity is not a severe problem, the analysis for H1 was also conducted on 85 percent and 90 percent of the ample.^

RESULTS

The hypotheses were tested using multiple regression analysis. For each hypothesis,6 models were run separately for each of the dependent Hypothesis 2 variables: satisfaction with manufacturer support, satisfaction with profit, and dyadic sales. While Recall H2 stated that higher levels of communiconducting analyses in this fashion may result in cation quality, participation, and information an inflated Type 1 error rate, this approach is sharing are associated with more successful consistent with other research (e.g., Kohli, partnerships, compared to less successful partner1989b). As an additional precaution, we also ships. The multivariate test for H2 was significant compared the findings with a multivariate multiple (Wilks Lambda = 9.49, p < 0.001). Table regression approach (e.g., Sinha, 1990). The 3 shows that as communication quality and multivariate statistics are also reported with participation are higher, satisfaction with manueach hypothesis. The multivariate findings are facturer support is higher (participation at significant for all three hypotheses, with univari- p < 0.10). Interestingly, as information sharing ate tests confirming those found with standard is higher, satisfaction with profit is lower. Participation is the only significant predictor of regression techniques. The handling of the covariate in the regression dyadic sales. Thus, H2 receives partial support. equations followed guidelines suggested by Cohen and Cohen (1983). As indicated, the covariate Hypothesis 3 was added to the model before adding the independent variables in order to partial out its Hypothesis 3 stated that the use of constructive effects prior to hypothesis testing (see also the conflict resolution techniques is positively associChange in F statistic reported in Tables 2 4 ) . ated with more successful partnerships, compared The regression assumptions were tested for to less successful partnerships, and that the use outliers and for normality of the residuals and of destructive conflict resolution techniques is revealed no problems. negatively associated with successful partnerships. The multivariate test for H3 was significant (Wilks Lambda = 4.03, p < 0.001). Table 4 These analyses are premised upon the notion that, if shows that joint problem solving is significantly multicollinearity is present, beta coefficients are unstable. related to satisfaction with manufacturer support. To the extent that the estimated coefficients are similar (i.e., remain stable) in sign and magnitude on subsets of the data, Both severe resolution tactics (harsh words and one can infer that multicollinearity is not affecting the results domination) and smoothing over problems are (cf. Kohli, 1989a). Hence, the hypotheses were tested three negatively associated with satisfaction with profit, times--once on 100 percent o f the sample, again on 85 percent of the sample, and a third time on 90 percent of the while arbitration is positively associated with sample. The beta coefficients remained stable in each of the satisfaction with profit (p < 0.10). The regression analyses, indicating that multicollinearity was likely not equation for dyadic sales as the dependent influencing the results. We also ran the analyses in one overall regression equation. variable is not significant. Thus, H3 also receives Results were similar to those presented here. partial support.

Recall H1 posited that higher levels of commitment, coordination, trust, and interdependence are associated with more successful partnerships, compared to less successful partnerships. The results for H1 are shown in Table 2. The multivariate test was significant (Wilks Lambda = 7.68, p < 0.001). As Table 2 shows, commitment and coordination are positively associated with satisfaction with manufacturer support. Trust is significantly associated with satisfaction with profit. Predictors of dyadic sales include both commitment and coordination. Interdependence is not significantly related to any of the dependent variables.

Characteristics of Partnership Success

Table 2. Beta coefficients from regression analyses for H1 Dependent variables:

Covariate: Closeness Independent variables: Commitment Coordination Trust Interdependence Change in F df

A

145

Satis. with mftr support

Satis. with profit

Dyadic sales (log)

0.57** * 0.22** 0.42***

0.39***

0.18 0.28** 0.32**

11.95** * 5/96 0.53***

2.52* 5/96 0.19***

5.23*** 5/96 0.16** *

R2adjusted for df.

A

The change in F-statistic shows the significance of the variance explained by the independent variables after accounting for (partialing out) the variance explained by the covariate.

'

< 0.10; * p < 0.05; *'p < 0.01;*** p < 0.001; -nonsignificant

Table 3. Beta coefficients from regression analysis for H2 Dependent variables:

Covariate: Closeness Independent variables: Commun. quality Information sharing Participation Change in F df

~

f t r Satis. with m support

0.57*** 0.48***

Satis. with profit

Dyadic sales (log)

0.39***

-

0.18 *

0.14

*

-0.20*

0.45*** 7.97*** 4/97 0.19***

13.79*** 4/97 0.51***

3.08* 4/97 0.19***

R2 adjusted for df

A

The change in F-statistic shows the significance of the variance explained by the independent variables afrer accounting for (partialing out) the variance explained by the covariate

< 0.10; * p < 0.05; * * p < 0.01;* * * p < 0.001; -nonsignificant

DISCUSSION

The following variables were found to be significant in predicting the success of the partnership (either satisfaction or sales): coordination, commitment, trust, communication quality, information sharing, participation, joint problem solving, and avoiding the use of smoothing over problems or severe resolution tactics

(both negatively related to satisfaction with profit). Our research suggests that as these variables are present in greater amounts, the success of the partnership is likely to be greater. Interdependence, and persuasive tactics as a method to resolve conflict were found not to be predictors of partnership success. The strong, consistent findings for coordination as a predictor of partnership success are similar to

146

J . Mohr and R. Spekman

Table 4. Beta coefficients from regression analysis for H3 Dependent variables:

~~ ~~

Satis. with mftr

SUPPO*

Satis. with profit

Dyadic sales (log)

0.18

Covariate:

Closeness

Independent variables: Joint problem solving

0.57***

0.39** *

Persuade Severe resolution Smooth Arbitration

Change in F

3.31***

2.88*

6/95

df

adjusted for df

6/95

0.39***

6195

0.22***

p- < 0.10; * p < 0.05; * * p < 0.01; * * * p < 0.001; - nonsignificant The change in F-statistic shows the significance of the variance explained by the independent variables after accounting for (partialing out) the variance explained by the covariate.

other findings on closer business relationships. Frazier et al. (1988) suggested in their study of Just-in-Time relationships that high levels of coordination are associated with mutually fulfilled expectations. The findings for trust and commitment are also consistent with emerging research on partnering relationships. Anderson and Narus (1990) and Anderson and Weitz (1992) suggest that such feelings are important in mollifying a partners fear of opportunistic behavior. In particular, the relationship between Trust and Satisfaction with Profits is interesting. Profits derived from a particular vendor might contribute t o a dealers feeling of vulnerability. Powerful, and popular, manufacturers tend not to give the best margins. Yet, believing that the vendor will act fairly and in the best interest of the relationship might serve to calm the dealers fear of opportunistic behavior and might lead to greater perceived satisfaction with this aspect of the partnership. This study adds credence t o the notion that communication problems are associated with a lack of success in strategic alliances (Mohr, 1989; Sullivan and Peterson, 1982). Without communication quality and participation, the success of the partnership is placed in doubt.

The importance of communication becomes critical in signaling future intentions and might be interpreted as an overt manifestation of more subtle phenomena such as trust and commitment. These findings are consistent with Anderson et al. (1987) who found that mutual participation was associated with resource allocation among channel members. The negative association between Information Sharing and Satisfaction with Profits is both counter-intuitive and inconsistent with this discussion. It is possible, however, that greater information sharing may give the dealer the impression that he/she is entitled to a greater share of the fruits of the partnership, as evidenced by higher margins from the manufacturer. Greater information transfer might be interpreted as closeness between manufacturer and dealer in which margins are viewed, albeit incorrectly, as joint property. This study indicates that the manner in which conflict is resolved has an impact on relationship success. Joint problem solving, whereby grievances are aired and the underlying issues are brought to the surface, fosters a win-win solution between partners. Arbitration has also been beneficial to the success of the relationship in extreme conflict situations. Anderson and

Characteristics of Partnership Success

Narus (1990) indicate that distributor councils and distributor ombudsmen are two mechanisms by which conflicts can be diffused and settled constructively. A t the same time, arbitration is viewed by some (Assael, 1969) as an effective but a less preferred conflict resolution mechanism when compared with internal solutions. Harsh Words and Smoothing Over Problems as conflict resolution modes do little to uncover the underlying problems associated with conflict and tend to exacerbate the fundamental differences that exist between trading partners. Both serve to solve short-term difficulties but do not begin to address the longer-term issues that might affect the relationship. Neither of these conflict resolution mechanisms work towards joint resolution of problems nor do they focus on information sharing and communication as important components of problem solving. The nonsignificant findings in this study bear discussion. Interdependence was not related to any of the measures of partnership success. The nonsignificance of this relationship may be due, in part, to the measure used by interdependence. Interdependence may be more than each partys dependence on the other, and may include issues of magnitude as well as symmetry (Gundlach and Cadotte, 1989). The measures for Communication Behavior appeared to do a better job of predicting the more qualitative aspects of partnership success; only participation was significantly related t o the quantitative outcome of sales. Communication Behaviors may eventually impact quantitative outcomes such as sales volume in a two-step process in which higher levels of satisfaction are associated with more effort on behalf of the partnership; eventually these efforts are associated with increased performance (Mohr and Nevin, 1990). The fact that none of the conflict resolution modes was significantly related to Dyadic Sales is surprising-and only one of the modes, Joint Problem Solving-was related to Satisfaction with Support. These nonsignificant findings may be explained by the use of single-item measures, o r by the two-step process mentioned for Communication Behaviors previously. The findings from this research, as in all research, must be tempered by the limitations of the study. Clearly, the findings are contingent upon the context and the type of partnerships

147

studied-partnerships between computer manufacturers and their dealers. The generalizability of these results across a broad range of strategic partnerships is cautioned. In addition, data were collected from only one side of the dyad-the manufacturers perceptions of the partnership remain unknown. Data were collected from only a single informant from the dealers organization. While use of a single informant met Campbells (1955) criteria, it is clear that these respondents were providing their perceptions of organizational-level phenomena. In any study, it is important to control for alternative explanations of the findings. Two alternative explanations for these results could be that the size of the dealer, the closeness of the relationships, or the length of the relationship accounted for the findings. In this study, the size of the dealer was explicitly controlled for in testing the hypotheses related to sales (by adjusting the sales measure). (Size was unrelated to the satisfaction measures; hence, it was unnecessary to add as a control variable for those hypotheses). Closeness of the relationship was explicitly added as a covariate in all analysis, so the results cannot be explained by the degree of closeness of the partnership. Length of relationship duration was uncorrelated with the two satisfaction measures (and therefore was unnecessary as a control variable) and significantly correlated with the Dyadic Sales measure. However, when adding length of the relationship as a control variable, the results remain unchanged. Finally, there might exist a common method variance problem since data on both the dependent and independent variables were collected from the same respondent. However, two possibilities mitigate against such an explanation for the results. First, the questionnaire was fairly lengthy, addressing aspects of manufacturerldealer relationships beyond those used in this study. It is unlikely that respondents would have been able to guess the purpose of the study and forced their answers to be consistent. Second, the dependent variables asked not only for perceptual data, but also objective (sales) data. Objective data are less likely to be subject to halo effects than are affective/perceptual data (i. e., satisfaction measures).

148

J . Mohr and R. Spekman

likely that managers feel they are trading one set of risks and uncertainty for another. In a number of instances, partners are unprepared to answer questions related to the management of this new relationship, and research has not systematically addressed the array of skills needed to help ensure that the partners mutual goals are achieved. The managerial implications to be drawn from this research relate to the manner in which partners attempt to manage the future scope and tone of their relationship. Trust, commitment, communication quality, joint planning, and joint problem resolution all serve to better align partners expectations, goals, and objectives. These factors all contribute to partnership success. The challenge, however, lies in developing a management philosophy or corporate culture in which independent and autonomous trading parties can relinquish some sovereignty and control, while also engaging in planning and organizing which takes into account the needs of the other party. Such a wilful abdication of control (and autonomy) does not come easily but appears to be a necessary managerial requirement for the future. For example, Corning, a company admired for its partnering acumen, espouses corporate values that add credence to our results. While it would seem that similarities across organizational cultures would improve the probability of partnership success (see Harrigan, 1988), such compatibility cannot be ensured. In many cases. differences in culture, operating procedures, and practices become apparent only during the course of the partnership. Effort must be dedicated to the formation and implementation of management strategies that promote and encourage the continued growth and maintenance of the partnership. In light of the scant and fragmented nature of the literature which address those factors that differentiate successful from unsuccessful partnerships, this research has attempted to clarify this problem. Managerially, such research offers insight into how to proactively manage partnerships in order to reap the benefits of success, and to avoid the damaging costs inherent in their failure. Theoretically, a specification of the linkages between characteristics of the partnership and its success can provide a useful framework for future research. The empirical test reported

CONCLUSIONS

The rationale for and the decision to form strategic partnerships appears to be fairly welldocumented both in the marketing and strategy literatures as well as in the trade press. However, very little guidance exists regarding the processes required to develop and nurture the partnership beyond the initial decision to forge such a relationship. Given both the costs and risks associated with mismanaging a potentially valuable partnership, insight into the factors affecting partnership success is quite useful. This research sheds light on these issues and offers an improved understanding of the form and substance of the interaction between partners. This study suggests that trust, the willingness to coordinate activities, and the ability to convey a sense of commitment to the relationship are key. Critical also to partnership success are the communications strategies used by the trading parties. The quality of information transmitted and the joint participation by partners in planning and goal setting send very important signals to the trading parties. Recent pronouncements by both P & G and Wal-Mart, for example, who have dedicated resources for the sole purpose of effectively managing the interface between these two firms, support our findings. Although the level of magnitude is quite different, the fundamental processes and mechanisms mirror our results and add support. Joint participation enables both parties to better understand the strategic choices facing each other. Such openness is not natural for management and it must develop its communications skills and learn to accommodate/modify its traditional concern for decision autonomy. This skill is nontrivial to the success of the partnership. Management must also move towards processes and behavioral mechanisms that support working with another firm to achieve mutually beneficial goals. Consistent with this view is the importance of joint problem solving as a conflict resolution mechanism. The partners ability to take the others perspective and attempt to reconcile differences improves problem solving. While we demonstrate that certain characteristics and processes are associated with partnership success, there is a certain irony that arises in managing these partnerships. That is, it is

Characteristics of Partnership Success

here provides a first attempt to better understand partnership success and the factors that contribute to success.

149

arrangements as strategic alliances: Theoretical issues in organizational combinations, Academy of Management Review, 14, pp. 234-249. Business Week (July 17, 1989). The power surge at computer dealers, pp. 134-135. Business Week (July 1, 1989). PC slump? What PC slump?, pp. 66-67. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Campbell, D. (1955). The informant in quantitative research, American Journal of Sociology, 60, The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful pp. 339-342. comments of Jan Heide, Michael Lawless, Jack Churchill, G. A., Jr. (February 1979). A paradigm Nevin, and Linda Price, and three anonymous for developing better measures of marketing constructs, Journal of Marketing Research, 16, SMJ reviewers on this paper. pp. 64-73. Cohen, J. and P. Cohen (1983). Applied MuItiple RegressionlCorrelation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, (2nd ed). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, REFERENCES Hillsdale. NJ. Achrol, R.,L, Scheer and L. Stern (1990). Designing Computer Reseller News (1988). Research Publications successful transorganizational marketing alliances, from Media Kit, CMP Publications, Manhasset, NY. K. (Winter 1977). Exchange and power in Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA, Report #90-118. networks of interorganizational relations, The Anderson, E. (1985). The salesperson as outside Sociological Quarterly, 187 pp. 62-82. agent or employee: A transaction cost analysis, Cook, T. C. and D. T. Campbell (1979). QuasiExperimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Marketing Science, 4, pp. 234-254. Rand McNally, Chicago, IL. Anderson, E. and B. Weitz (1986). Make or buy Cummings T. (1984). Transorganizational developdecisions: Vertical integration and marketing proin, Organizational Behavior, 6 , ductivity, Sloan Management ~ ~ 27,pp. ~ 3-20. i ment, ~ Research ~ pp. 367-422. Anderson, E. and B. Weitz (February 1992). The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment Daft, R. and R. Lengel (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness, and in distribution channels, Journal of Marketing structural design, Management Science, 32 ( 5 ) , Research, 29, pp. 18-34. pp. 554-571. Anderson, E., L. Lodish and B. Weitz (February 1987). Resource allocation behavior in conventional Day* G. and s. K1ein (19g7). Cooperative behavior In vertical markets: The influence of transaction channels, of Marketing Research, 24, costs and competitive strategies. In M. Houston pp. 85-97. (ed.)7 Review O f pp. 39-66. Anderson, J. and J. Narus (Fall 1984). A model of the distributor~s perspective of distributor- Deutsch, M. (1969). Conflicts: Productive and destructive, Journal of Social Issues, 25 (1). pp. 7-41. manufacturer working relationships, Journal of Devlin, G. and M. Bleackley (1988). Strategic Marketing, 48, pp. 62-74. for success, Long Range Anderson, J. and J. Narus (January 1990). A model Planning, 2 1 (9,pp. 18-23. of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working Driscoll, J. (1978). Trust and participation in organizapartners hips^, ~~~~~l of Marketing, 54, pp. 42-58. tional decision making as predictors of satisfaction, Angle, H, and J , Perry (March 1981). An empirical Academy Of Management Journalt 21 pp. 44-56. assessment o f organizational commitment and 1988). A tKUKactions organizational effectiveness, Administrative Science Dwyer, F. R. and s. Oh cost perspective on vertical contractual structure Quarterly, 26, pp. 1-14. and interchannel competitive strategies, Journal of Armstrong, J. S. and T. Overton (July 1977). EstimatMarketing, 52, pp. 21-34. ing nonresponse bias in mail surveys, Journal of Dwyer, F. R., P. Schurr and S. Oh (April 1987). Marketing Research, 51, pp. 71-86. buyer-seller relationships, Journal of Assael, H. (December 1969). Constructive role of Marketing9 51 pp. 11-27. interorganizational conflict, Administrative Science Frazier, G. (Fall P983). Interorganizational exchange Quarterly, 14,pp. 573-582. behavior in marketing channels: A broadened Benson, J. K. (June 1975). The interorganizational ~rspective~ Of PP. 68-78. network as a political economy, Administrative Frazier, G., R. Spekman and C. ONeal (October Science Quarterly, 20, pp. 229-249. 1988). Just-in-time exchange relationships in indusBertrand, K. (May 1989), The channel challenge, trial markets, Journal of Marketing, 52, pp. 52-67. Business Marketing, pp. 42-50. Bleeke, J. and D. Ernst (November-December 1991). Govindaralan, v. (1988). A contingency approach to strategy implementation at the business-unit level: meway to win in cross-border ~~~~~~d Integrating administrative mechanisms with stratBusiness Review, pp. 127-135. %Y, Academy Of Management Journal, 31 (4). Borys, B. and D. Jemison (April 1989). Hybrid pp. 828-853.

Cooky

3

4 7 7

150

J . Mohr and R . Spekman

terly, 5 , pp. 583-601. MacNeil, I. (1981). Economic analysis of contractual relations: Its shortfalls and the need for a rich classificatory apparatus, Northwestern University Law Review, 7 5 , pp. 1018-1063. Mason, C. and W. Perreault (August 1991). Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis, Journal of Marketing Research, 28, pp. 268-280. McDougall, P. and R. Robinson, Jr. (October 1990). New venture strategies: An empirical identification of eight archetypes of competitive strategies for entry, Strategic Management Journal, 11, pp. 447-467. Mohr, J. (1989). Communicating with industrial customers, Marketing Science Institute, Report No. 89-112. Cambridge, MA. Mohr, J. and J. R. Nevin (October 1990). Communication strategies in marketing channels: A theoretical perspective, Journal of Marketing, 54, pp. 36-51. Narus, J. and J. Anderson (September-October 1977). Distributor contributions to partnerships with manufacturers, Business Horizons, 30, pp. 34-42. Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory (2nd ed). McGraw-Hill, New York. Pearce, J. A. I1 and S. A. Zahra (February 1991). The relative power of CEOs and boards of directors: Associations with corporate performance, Strategic Management Journal, 12, pp. 135-154. Pfeffer, J. and G. R. Salancik (1978). The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Harper and Row, New York. Phillips, L. (November 1981). Assessing measurement error in key informant reports: A methodological note on organizational analysis in marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, 18, pp. 395-415. Porter. L., R. Steers, R. Mowday, and P. Boulian (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians, Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, pp. 603-609. Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free Press, New York. Powell, W. (1987). Hybrid organizational arrangements: New form or transitional development, California Management Review, 30 ( l ) , pp. 67-87. Powell, W. (1990). Neither market nor hierarchy, Research in Organizational Behavior, 12, pp. 295-336. Provan, K. (1984). Interorganizational cooperation and decision making autonomy in a consortium multihospital system, Academy of Management Review, 9, pp. 494-504. Pruitt, D. G. (1981). Negotiation Behavior. Academic Press, New York. Ruekert, R. and G. A. Churchill, Jr. (May 1984). Reliability and validity of alternative measures of channel member satisfaction, Journal of Marketing Research, 21, pp. 226233. Ruckert, R. and 0. Walker (January 1987). Market-

Guetzkow, H , (1965). Communications in organizations. In J. March (ed.), Handbook of Organizations. Rand McNally and Company, Chicago, IL, pp. 534-573. Gundlach, G. and E. Cadotte (1989). Manufacturer and distributor interdependence as a predictor of interorganizational interaction and outcomes, Working Paper, University of Notre Dame. Hamel, G., Y. Doz and C. K. Prahalad (January-February 1989). Collaborate with your competitors-and win, Harvard Business Review, pp. 133-139. Harrigan, K. R. (1985). Vertical integration and corporate strategy, Academy of Management Journal, 28 (2), pp. 397425. Harrigan, K. R. (1988). Strategic alliances and partner asymmetries, Management International Review, 28 (Special Issue), pp. 53-72. Heide, J. and G . John (February 1990). Alliances in industrial purchasing: The determinants of joint action in buyer-supplier relationships, Journal of Marketing Research, 27, pp. 24-36. Howell, R. (February 1987). Covariance structure modeling and measurement issues: A note on interrelations among a channel entitys power sources, Journal of Marketing Research, 24, pp. 119-126. Huber, G. and R. Daft (1987). The information environment of organizations. In F. Jablin et al. (ed.), Handbook of Organizational Communication. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA. pp. 130-164. Jablin, F., L. Putnam, K. Roberts and L. Porter (1987). Handbook of Organizational Communication. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA. John, G. (August 1984). An empirical investigation of some antecedents of opportunism in a marketing channel, Journal of Marketing Research, 21, pp. 278-289. Johnston, R. and P. Lawrence (July-August 1988). Beyond vertical integration-the rise of the valueadding partnership, Harvard Business Review, pp. 94-101. Kanter, R. M. (1988). The new alliances: How strategic partnerships are reshaping American business. In H. Sawyer (ed.), Business in a Contemporary World. University Press of America, New York, pp. 59-82. Kapp, J. and G . Barnett (1983). Predicting organizational effectiveness from communication activities: A multiple indicator model, Human Communication Research, 9, pp. 239-254. Kohli, A. (July 1989a). Determinants of influence in organizational buying: A contingency approach, Journal of Marketing, 53, pp. 5 M 5 . Kohli, A. (October 1989b). Effects of supervisory behavior: The role of individual differences among salespeople, Journal of Marketing, 53, pp. W 5 0 . Levine, J. and J. Byrne (July 21, 1986). Odd couples, Business Week. pp. 100-106. Levine, S. and P. White (1962). Exchange as a conceptual framework for the study of interorganizational relations, Administrative Science Quar-

Characteristics of Partnership Success

ings interaction with other functional units: A conceptual framework and empirical evidence, Journal of Marketing, 51, pp. 1-19. Salmond, D. and R. Spekman (1986). Collaboration as a mode of managing long-term buyer-seller relationships. In T. Shimp et al. (eds), A M A Educators Proceedings, American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL, pp. 162-166. Schuler, R. (1979). A role perception transactional process model for organizational communicationoutcome relationships, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23, pp. 260-291. Sethurman, R., J. Anderson, and J. Narus (1988). Partnership advantage and its determinants in distributor and manufacturer working relationships, Journal of Business research, 17, pp. 327-347. Sinha, D. (October 1990). The contribution of formal planning to decisions, Strategic Management Journal, 11, pp. 479-492. Snyder, R. and J. Morris (1984). Organizational communication and performance, Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, pp. 461-465. Spekman, R. and K. Gronhaug (1986). Methodological issues in buying center research, European Journal of Marketing, 20, pp. 50-63. Spekman, R. and D. Salmond (1992). A working consensus to collaborate: A field study of manufacturer-supplier dyads, Report #92-134. Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA. Stern, L. and T. Reve (Summer 1980). Distribution channels as political economies: A framework for comparative analysis, Journal of Marketing, 44, pp. 52-64. Stohl, C. and W. C. Redding (1987). Messages and message exchange processes. In F. Jablin et al. (eds), Handbook of Organizational Communication: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 451-502. Sullivan,J. and R. B. Peterson (1982). Factorsassociated with trust in Japanese-American joint ventures, Management International Review, 22, pp. 30-40. Thomas, K. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. Dunnette (ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Rand McNally , Chicago, IL, pp. 889-935. Thompson, J. (1967). Organizations in Action. McGraw-Hill, New York. Varadarajan, P. R. and D. Rajaratnam (January 1986). Symbiotic marketing revisited, Journal of Marketing, 50, pp. 7-17. Weiss, A. and E. Anderson (February 1992). Converting from independent to employee salesforces: The role of perceived switching costs, Journal of Marketing Research, 29, pp. 101-115. Williamson, 0. (1975). Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. Free PressMacmillan, New York. Williamson, 0. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. The Free Press, New York. Zand, D. (1972). Trust and managerial problem solving, Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, pp. 229-239.

151

APPENDIX: ITEMS *

Indicators of success

Dyadic sales volume of the referent manufacturers product:

What is your approximate volume of sales of this manufacturers product, on a monthly basis? (Seven categories) What are the total monthly sales of your dealership? (seven categories); multiplied by: Of the total sales of your dealership, what percent comes from this manufacturers product? (0%/100% in 10% increments)

Satisfaction: How satisfied are you with the following aspects of the relationship with this manufacturer? (Very dissatisfiedhery satisfied) Personal dealings with manufacturers sales reps Assistance in managing inventory Cooperative advertising support Promotional support (coupons, rebates, displays) Off-invoice promotional allowances Profit on sales of manufacturers product

How does this manufacturers product stack up t o its closest competitors on reseller margins? (LowedHigher)

Attributes of the partnership (Strongly disagree/

strongly agree) Commitment: Wed like t o discontinue carrying this manufacturers product (reverse scored). We are very committed t o carrying this manufacturers products. We have a minimal commitment t o this manufacturer (reverse scored).

Coordination: Programs at the local level are well coordinated with the manufacturers national programs. We feel like we never know what we are supposed to be doing or when we are supposed to be doing it for this manufacturers product (reverse scored). * *

152

J . Mohr and R. Spekman

In this relationship, it is expected that any information which might help the other party will be provided. The parties are expected to keep each other informed about events or changes that may affect the other party. It is expected that the parties will only provide information according to prespecified agreements (reverse scored). * * We do not volunteer much information regarding our business to the manufacturer (reverse scored).* * This manufacturer keeps us fully informed about issues that affect our business.** This manufacturer shares proprietary information with us (e.g., about products in development, etc.). * *

Conflict resolution techniques Assuming that some conflict exists over program and policy issues and how you implement the manufacturers programs, how frequently are the following methods used to resolve such conflict? Smooth over the problem Persuasive attempts by either party Joint problem solving Harsh words Outside arbitration Manufacturer-imposed domination (Very infrequentlyhery frequently) Covariate for strategic partnership (Strongly disagreehtrongly agree) In this relationship, the parties work together to solve problems. The manufacturer is flexible in response to requests we make. The manufacturer makes an effort to help us during emergencies. When an agreement is made, we can always rely on the manufacturer to fulfill all the requirements.

* All items are on a 5-point scale with the endpoints labeled as shown in parentheses, except where noted. * * Variable eliminated during scale purification.

Our activities with the manufacturer are well coordinated.

Trust: (Strongly disagree/strongly agree) We trust that the manufacturers decisions will be beneficial to our business. We feel that we do not get a fair deal from this manufacturer. This relationship is marked by a high degree of harmony. Interdependence: (Strongly disagree/strongly agree) If we wanted to. we could switch to another manufacturers product quite easily (reversescored). If the manufacturer wanted to, they could easily switch to another reseller (reverse-scored). Communication behavior Communication Quality: To what extent do you feel that your communication with this manufacturer is: Timelyhntimely Accuratehnaccurate Adequatetinadequate Comple te/incomple te Credibfelnot credible Participation: (Strongly disagreelstrongly agree) Our advice and counsel is sought by this manufacturer. We participate in goal setting and forecasting with this manufacturer. We help the manufacturer in its planning activities. Suggestions by us are encouraged by this manufacturer. Information sharing (Strongly disagree/strongly agree) We share proprietary information with this manufacturer. We inform the manufacturer in advance of changing needs.

You might also like

- Progress Test Files 1 5 Answer Key A. Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation GRAMMAR PDFDocument8 pagesProgress Test Files 1 5 Answer Key A. Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation GRAMMAR PDFsamanta50% (2)

- Summary Corporate DiversificationDocument3 pagesSummary Corporate DiversificationVoip Kredisi0% (1)

- Strategies For Successful Interpersonal CommunicationDocument14 pagesStrategies For Successful Interpersonal CommunicationHamza ShahNo ratings yet

- ERP Next: by Mohammed Ibrahim (1891029) Jaladhi Sonagara (1991106)Document12 pagesERP Next: by Mohammed Ibrahim (1891029) Jaladhi Sonagara (1991106)jaldhi sonagaraNo ratings yet

- Writing For Impact 3a-4b (With Key)Document49 pagesWriting For Impact 3a-4b (With Key)Tâm Lê Văn50% (2)

- j1939 ProtocolDocument2 pagesj1939 ProtocolFaraz ElectronicNo ratings yet

- Partnership General 1Document19 pagesPartnership General 1Angela Aprina Kartika PutriNo ratings yet

- Strategic Alliances-Factors Influencing Success and Failure AbstractDocument24 pagesStrategic Alliances-Factors Influencing Success and Failure AbstractSanjay DhageNo ratings yet

- Business To Business Relationships The VDocument10 pagesBusiness To Business Relationships The VOtun OlusholaNo ratings yet

- Bagi Chapter 10 External RelationshipsDocument18 pagesBagi Chapter 10 External RelationshipsNanda Mulia SariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tugas 4Document10 pagesJurnal Tugas 4Pranggara DimassiwiNo ratings yet

- The Power of Partnership Why Do Some Strategic Alliances Succeed, While Others Fail?Document6 pagesThe Power of Partnership Why Do Some Strategic Alliances Succeed, While Others Fail?Vinay KumarNo ratings yet

- Anderson 1990Document18 pagesAnderson 1990monya monyaNo ratings yet

- Interfirm Rivalry and Managerial ComplexityDocument17 pagesInterfirm Rivalry and Managerial ComplexityNguyen Hung HaiNo ratings yet

- Relationship Marketing and Contract Theory PDFDocument14 pagesRelationship Marketing and Contract Theory PDFguru9anandNo ratings yet

- Business Relationship Development and The Influence of Psychic DistanceDocument9 pagesBusiness Relationship Development and The Influence of Psychic Distancesamriddhi sinhaNo ratings yet

- 1546121Document16 pages1546121Hammna AshrafNo ratings yet

- KMV ModelDocument20 pagesKMV ModelMinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Morgan and Hunt 1994 - Commitment and Trust in RMDocument20 pagesMorgan and Hunt 1994 - Commitment and Trust in RMTrần Xuân ĐứcNo ratings yet

- Inter-Organizational Communication As A Relational Competency - Antecedents and Performance Outcomes in Collaborative Buyer-Supplier RelationshipsDocument20 pagesInter-Organizational Communication As A Relational Competency - Antecedents and Performance Outcomes in Collaborative Buyer-Supplier RelationshipsPeter O'DriscollNo ratings yet

- Strategic AlliancesDocument22 pagesStrategic AlliancesAngel Anita100% (2)

- Neil NagyDocument32 pagesNeil Nagymasyuki1979No ratings yet

- 01 2017 Facteurs de Succès de L'alliance StrategiqueDocument9 pages01 2017 Facteurs de Succès de L'alliance StrategiqueYacintheNo ratings yet

- Causes and Outcomes of Satisfaction in Business RelationshipsDocument18 pagesCauses and Outcomes of Satisfaction in Business RelationshipsLuqman ZulkefliNo ratings yet

- SD& RG &GS Article (R)Document29 pagesSD& RG &GS Article (R)shailendra369No ratings yet

- The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship MarketingDocument20 pagesThe Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship MarketingAssal NassabNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Psychological Contracts Upon Trust and Commitment Within Supplier-Buyer Relationships: A Social Exchange ViewDocument21 pagesThe Impact of Psychological Contracts Upon Trust and Commitment Within Supplier-Buyer Relationships: A Social Exchange ViewCRNIPASNo ratings yet

- Kale2002 Alliance CapabilityDocument21 pagesKale2002 Alliance CapabilityJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- JV in SpainDocument18 pagesJV in SpainHaile Alex AbdisaNo ratings yet

- Miliad 1Document17 pagesMiliad 1Hosein MostafaviNo ratings yet

- Antecedents of Supplier-Retailer Relationship Commitment: An Empirical Study On Pharmaceutical Products in BangladeshDocument11 pagesAntecedents of Supplier-Retailer Relationship Commitment: An Empirical Study On Pharmaceutical Products in BangladeshiisteNo ratings yet

- Robert MDocument35 pagesRobert MNova KartikaNo ratings yet

- BM16-045OA R1 ArticleDocument33 pagesBM16-045OA R1 Articlezyn020530No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing The Effectiveness of Relationship MarketingDocument19 pagesFactors Influencing The Effectiveness of Relationship MarketingAizat DzmsNo ratings yet

- Relationship Marketing and The Consumer: Robert A. PetersonDocument4 pagesRelationship Marketing and The Consumer: Robert A. PetersonukrishnakumarNo ratings yet

- The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship MarketingDocument20 pagesThe Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship MarketingManoj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Alliances and NetworksDocument25 pagesAlliances and NetworksmirianalbertpiresNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Partner Fit of International Alliances: The Experience of Taiwanese Construction Consulting FirmsDocument17 pagesDynamic Partner Fit of International Alliances: The Experience of Taiwanese Construction Consulting FirmsArifaniRakhmaPutriNo ratings yet

- B Segrestin - Towards A New Form of Governance For Interfirm CooperationDocument15 pagesB Segrestin - Towards A New Form of Governance For Interfirm Cooperationbert.lacomb256No ratings yet

- Control Mechabinsim FranchiseDocument14 pagesControl Mechabinsim Franchiseapp.fivecloverNo ratings yet

- Trust and Corporate Performance: Sandra RothenbergerDocument20 pagesTrust and Corporate Performance: Sandra RothenbergerKeeZan LimNo ratings yet

- Banking IndustryDocument15 pagesBanking IndustryMallikarjun DNo ratings yet

- Title: Instructions For UseDocument31 pagesTitle: Instructions For UseYosart AdiNo ratings yet

- Marketing and LogisticsDocument25 pagesMarketing and LogisticsFodorean AuraNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Collaboration: What's Happening?Document20 pagesSupply Chain Collaboration: What's Happening?Kavitha Reddy GurrralaNo ratings yet

- Partnerships TadelisDocument30 pagesPartnerships TadelisM LNo ratings yet

- Journal of Management 1998 Das 21 42Document23 pagesJournal of Management 1998 Das 21 42Sourav JainNo ratings yet

- The Explanatory Foundations of Relationship Marketing TheoryDocument17 pagesThe Explanatory Foundations of Relationship Marketing TheoryAlberto CalvarioNo ratings yet