Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Indian Historical Review 2007 Chanana 324 7

Uploaded by

Mohit AnandCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Indian Historical Review 2007 Chanana 324 7

Uploaded by

Mohit AnandCopyright:

Available Formats

Indian Historical Review

http://ihr.sagepub.com/ The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices of Pakistan and India

Priyanka Chanana Indian Historical Review 2007 34: 324 DOI: 10.1177/037698360703400122 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ihr.sagepub.com/content/34/1/324.citation

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Indian Council of Historical Research

Additional services and information for Indian Historical Review can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ihr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ihr.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Jan 1, 2007 What is This?

Downloaded from ihr.sagepub.com by guest on February 19, 2013

324

The Indian Historical Review

1749. After this, the Mughal Empire lost all its credibility and the major parts of Rajputana were occupied by the Rajput chiefs. Thus the Mughal authority disappeared from Rajasthan. With this, the author successfully proves his point that the policy of the Mughal emperors towards the Rathors was imprudent and resorted to only in circumstances of 'urgency' or 'expediency'. Overall, Sangwan has presented a very coherent picture about the relations of the Rathor chiefs and the Mughal emperors and the prevalent factionalism at the Mughal court in the first half of the eighteenth century. However, in his conclusion, he writes about the changes in the Rathor society, which are not the part of his study. Besides this overstepping, the book regrettably suffers from numerous printing errors, which could have been avoided. Still the book is well-printed and would be useful for the researchers and students who are interested in the history of later Mughals and the Rajputs rulers of Rajasthan.

ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH

B.L. BHADANI

The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices ofPakistan and India (Oxford University Press, Karachi, 2003). Pp. xxx + 209. Rs 595.00.

SHEMEEM BURNEY ABBAS,

In the past few years there has been an attempt to restore the voices of women. The present work is an important contribution towards this direction. The work comes up as an important challenge to Western scholarship that describes Islam as a 'male' religion. The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual contributes to the field of Islam and Sufism in general and gender studies in particular. In fact, this is a 'first' attempt of its kind ever made. Abbas challenges the Western scholarship, which states that no women are observed in the mosques for prayers and that female participation is lacking during the major religious feasts, by showing not only the presence of women but also the contributions made by women in the Sufi practice of sama. Sufism, though based on the Quranic ideals, offered a platform where women did have an important role to play. Abbas' book is an attempt to bring a more nuanced understanding of Islam and women's place within it.

Downloaded from ihr.sagepub.com by guest on February 19, 2013

Reviews ofBooks

325

Since Sufism was tolerant towards religion, colour, caste and gender, Abbas attempts here to bring out the embedded voices of women within it. She suggests that the important spheres of religious and spiritual involvement for the women are the Sufi shrines. Abbas's study is a linguistic and anthropological research of discourse and poetry in devotional settings. Since earlier studies of Islam were based on textual evidence, she adds a new dimension to it by her extensive ground research and fieldwork in various Sufi shrines. Abbas attempts here to take her studies away from the mosque as the centre of all Islamic activities, and instead focuses on the alternative sites of religious practices, that is, the Sufi shrines, melas, concerts, etc. The text has been an attempt to make the silent voices' audible, that is, the female voices, which form an important aspect of 'the Sufi practice of sama, where both men and women participate in the rituals equally. Her work largely involves documentation of the performances and interviewing the renowned singers of Sufi poetry. She thereby traces the so-called 'voice' of women in such discourses. Besides this, she also documents the active participation of women in the support services in the shrines. The Sufi shrines not only fulfilled the devotional needs of the people who visited them but also provided an outlet from the chores of daily life. The study is largely centred on the oral culture of the subcontinent. The effort has largely been to bring out the voice of the women by references to the mystic veil, to women's work like grinding, husking, sewing, weaving, etc., and also by references to the myths of the female lovers like Hir, Sassi, Layla, Mira Bai and many more. By singing in voices, where the narrator is a woman, the poets are able to reach the masses that are generally illiterate. Abbas beautifully attempts to document the Sufi poetry' and especially what the Sufis sang about gender, class, caste and colour and how the discourse challenged the patriarchy through the device of the female speaker. Thus, Abbas claims that by using the female voice, the musicians express humility and surrender to a spiritual force (p. 143). Abbas claims that the work is the result of extensive research based on the archival materials that were a comprehensive collection of the multimedia resources from Pakistan, India, United Kingdom, France, United States and Canada from where Abbas found early examples of the women's roles as participants and performers in the Sufi rituals. To this was later added the ground research. By this way, The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual

Downloaded from ihr.sagepub.com by guest on February 19, 2013

326

The Indian Historical Review

is the first work of its kind focusing on the religious expression of women. But if one looks at the text historically, it tends to loose ground. Her understanding of the 'archives' is quite different from that of a historian. She also makes no note of the grants given to the women. Another interesting aspect is the difference between qawwali and the sufiana-kalam traditions, which Abbas brings out in the text. She suggests that qawwali is largely a male domain and requires rigorous training and that in sufiana-kalam females are also involved. During the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, the sufiana-kalam traditions, appeared in Sufism, in which poetry written in vernaculars was used by the Sufi poets. Abbas justifies that, as this model was an indigenous one that required minimal musical skills and resources, women's input in singing this poetry was visible. It is apparent that the present work is that of an anthropologist and thus lacks the insights of a historian. It appears that Abbas fails to trace the history of this 'female voice'. As such, the very understanding of the concept of female voice lacks explanation on its vertical (historical) dimension of origin and growth, though its presence is brought forth. It is also not clear as to what kind of female voice Abbas is trying to trace. Is it the suppressed voice of the grievances of women against the existing social and economic order? Or, is it the voice of the female singers of Sufi poetry, which is generally not written or talked about to avoid shame on the part of their families? Or, is it the voice of the disciple as the lover who sings or expresses her love jas a female lover towards the beloved, who is the murshid, a spiritual mentor, or Prophet, who is a male? Apart from this, the text appears to be too repetitive. It appears as if Abbas has been making a continuous effort to counter and clear the Western misconceptions by stressing on certain things. In a way, the work largely appears to be an answer to the Western scholarly understanding about the position of women within Islam. But the very claim by the author of herself being a 'native' itself gives rise to many questions. She herself has not been able to come out of that colonial hangover by addressing herself as 'native'. Further, if- one is trying to study women in Sufism, one cannot do so without significantly mentioning the contributions made by Rabi'a al-'Adawiyya towards the development of the mystical path and her

Downloaded from ihr.sagepub.com by guest on February 19, 2013

Reviews ofBooks

327

position within Sufism. She was the image of piety and her name stands prominent when one discusses women in Sufism. Abbas does mention Rabi'a and the famous work by Margaret Smith on Rabi'a, but only in passing without significantly pointing to the contributions she made and the esteemed position she holds within Sufi circles. Rabi'a's voice is a prominent female voice, which needs to be significantly acknowledged. Abbas also does not seem to have referred to any of the Sufi tazkirats and malfuzats, where many references to prominent women in Sufism, who were moral binding forces, have been made. No mention is made about Bibi Zulaikha, the mother of Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya, who was very pious and an important voice contributing in the moral and spiritual development of her son. Without bringing out the contributions by women like these, one cannot wholly locate the 'female voice' in the Sufi ritual. In spite of this, the work is worth appreciation, as it not only adds to the body of scholarship on Sufi Islam, but also significantly adds to the work on women and religion. It provides a platform on which further studies can be taken up.

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI PRIYANKA CHANANA

SHIVNATH, Jammu Miscellany (Kashmir Times Publications, Jammu, 2005). Pp. 155. Rs 250.00. This somewhat unusual book is a biographical profile of the state of Jammu. The book is by no means a consistently historical work, a task that has been fulfilled by other historians such as L.N. Dhar, Mohan Lal Kaul and many others who have written the history of Jammu and Kashmir. As a native of Jammu and a scholar-poet of Dogri, Shivnath has written an account of what is embedded deeply in the cultural fabric of the region, enmeshing facets of its history, folklore and literature. The first chapter is titled 'Jammu in Recorded History'. It is based on Persian texts like the Tarikh-i-Ferishta, written in the sixteenth century, the Malfuzat-e-Timuri or the later-day Persian chronicle Mukhtasar Taarikhe Jammu va Ryaasat-haai-maftooha Maharaja Gulab Singh Bahadur, by Maulavi Hashmat Ullah Khan Lakhnavi, as well as Dogri histories. The first historical mention of Jammu is in the Malfuzat-eTimuri, which refers to the defeat of its ruler Maldev in the fourteenth century by Timur.

Downloaded from ihr.sagepub.com by guest on February 19, 2013

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Cadence Tutorial EN1600Document30 pagesCadence Tutorial EN1600Vivek KevivNo ratings yet

- Designing Multi Layer To Balance SI by LeeRitcheyDocument85 pagesDesigning Multi Layer To Balance SI by LeeRitcheyram100% (1)

- Work EthicsDocument1 pageWork EthicsMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Gnss Antennas: An Introduction To Bandwidth, Gain Pattern, Polarization, and All ThatDocument6 pagesGnss Antennas: An Introduction To Bandwidth, Gain Pattern, Polarization, and All ThatMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Cadence Tutorial EN1600Document5 pagesCadence Tutorial EN1600Mohit AnandNo ratings yet

- 1797 LPKF Laser Direct Structuring enDocument16 pages1797 LPKF Laser Direct Structuring enAlfonso TamésNo ratings yet

- S-16-13-III (Music) PDFDocument32 pagesS-16-13-III (Music) PDFMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Antennas and Propagation: Chapter 5: Antenna ArraysDocument35 pagesAntennas and Propagation: Chapter 5: Antenna ArraysMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Tai-Saw Technology Co., LTD.: Approval Sheet For Product SpecificationDocument6 pagesTai-Saw Technology Co., LTD.: Approval Sheet For Product SpecificationMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Letterfor Websitelatest - 2 PDFDocument1 pageLetterfor Websitelatest - 2 PDFAbdiNo ratings yet

- 146Document3 pages146Mohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Single-Chip Global Positioning System Receiver Front-End: General Description FeaturesDocument9 pagesSingle-Chip Global Positioning System Receiver Front-End: General Description FeaturesMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Study - PCB Dimension (Length) : Evaluation Board VSWR & Efficiency (Simulation Results)Document6 pagesStudy - PCB Dimension (Length) : Evaluation Board VSWR & Efficiency (Simulation Results)Mohit AnandNo ratings yet

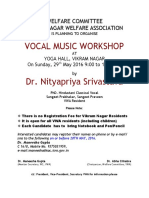

- Vocal WorkshopDocument1 pageVocal WorkshopMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Bhabha Atomic Research Centre Ph.D. Programme in Basic Sciences-2015Document1 pageBhabha Atomic Research Centre Ph.D. Programme in Basic Sciences-2015Mohit AnandNo ratings yet

- SL1206 SL1204 Electrical Guide v10Document5 pagesSL1206 SL1204 Electrical Guide v10Mohit AnandNo ratings yet

- ShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedDocument2 pagesShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Madariya Silsila in Indian PerspectiveDocument48 pagesMadariya Silsila in Indian PerspectiveJudhajit Sarkar100% (2)

- ShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedDocument2 pagesShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- ShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedDocument2 pagesShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- The PersianDocument100 pagesThe PersianMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Unicode SolutionDocument4 pagesUnicode SolutionMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Bangha Rekhta PDFDocument32 pagesBangha Rekhta PDFMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Bhabha Atomic Research Centre Ph.D. Programme in Basic Sciences-2015Document1 pageBhabha Atomic Research Centre Ph.D. Programme in Basic Sciences-2015Mohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Academic QualificationDocument16 pagesAcademic QualificationMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Wireless ChargingDocument12 pagesWireless ChargingMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- Wireless Charging of Mobile Phone Using Microwaves or Radio Frequency SignalsDocument3 pagesWireless Charging of Mobile Phone Using Microwaves or Radio Frequency SignalsMohit AnandNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- State of The Ummah Book 7.0Document85 pagesState of The Ummah Book 7.0PeterNo ratings yet

- Links by Arif - Sheet8Document1 pageLinks by Arif - Sheet8Arif RahmanNo ratings yet

- Choral SpeakingDocument13 pagesChoral SpeakingSyafie Abd WahabNo ratings yet

- Islamiyat PresentationDocument10 pagesIslamiyat PresentationMustafa BaigNo ratings yet

- Great Sayings of Great Person:prophet Muhammad (S.a.w)Document10 pagesGreat Sayings of Great Person:prophet Muhammad (S.a.w)Maimoona KhanNo ratings yet

- Arch242 Allnotes YalahwyDocument836 pagesArch242 Allnotes YalahwysamaaNo ratings yet

- Sir Syed Ahmed KhanDocument4 pagesSir Syed Ahmed KhanNeelam ZahraNo ratings yet

- Ibn Taymiyya BibliographieDocument19 pagesIbn Taymiyya BibliographieRémi GomezNo ratings yet

- How Many Hoors (Hoor Al-Ayn/houris) Will Be Given To A Muslim Man in Jannah (Paradise)Document6 pagesHow Many Hoors (Hoor Al-Ayn/houris) Will Be Given To A Muslim Man in Jannah (Paradise)yasir_009280% (10)

- Moroccan Female Religious AgentsDocument179 pagesMoroccan Female Religious AgentsCmcf TiceNo ratings yet

- Special DeputiesDocument62 pagesSpecial DeputiesMuhammad Seerat AliNo ratings yet

- The Deviations: Asif IftikharDocument3 pagesThe Deviations: Asif IftikharMuhammad MirNo ratings yet

- Dan GibsonDocument3 pagesDan GibsonMohd Shafri ShariffNo ratings yet

- Fatwa From QatarDocument3 pagesFatwa From QatarSyed Moosa KaleemNo ratings yet

- AKTIVITIDocument9 pagesAKTIVITILizam JeNo ratings yet

- Form Registrasi Lomba Mewarnai (Jawaban)Document9 pagesForm Registrasi Lomba Mewarnai (Jawaban)Andy PranataNo ratings yet

- 8C - Worksheet - We Must Not Litter. Expression of Prohibition (Larangan) (Responses)Document1 page8C - Worksheet - We Must Not Litter. Expression of Prohibition (Larangan) (Responses)YasirNo ratings yet

- Al Masih Ad-DajjalDocument21 pagesAl Masih Ad-DajjalJohn CollinsNo ratings yet

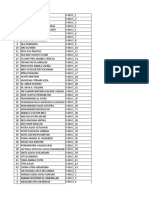

- No Nis Lokal Nisn NamaDocument12 pagesNo Nis Lokal Nisn NamaPrasdiNo ratings yet

- Kite Runner UnitDocument128 pagesKite Runner Unitalfredqj7No ratings yet

- Karabakh Carpet Chelebi. The Origin of The Carpet and The Symbolism of Its MotivesDocument20 pagesKarabakh Carpet Chelebi. The Origin of The Carpet and The Symbolism of Its MotivesТелман ИбрагимовNo ratings yet

- Environmentalism in The Quran, 2018Document8 pagesEnvironmentalism in The Quran, 2018Arifin Muhammad AdeNo ratings yet

- Absen 22-23 Per 25-11-22Document45 pagesAbsen 22-23 Per 25-11-22Destio WirantoNo ratings yet

- Zabur-e-Ajam-73 Part 2-12 Khizr-e-Waqt Az Khalwat Dasht-e-Hijaz Ayad Barun خضر وقت از خلوت دشت حجاز آ - 2Document10 pagesZabur-e-Ajam-73 Part 2-12 Khizr-e-Waqt Az Khalwat Dasht-e-Hijaz Ayad Barun خضر وقت از خلوت دشت حجاز آ - 2aftab20No ratings yet

- Member List Picture Root File - 901-1100Document31 pagesMember List Picture Root File - 901-1100Tabassum RezaNo ratings yet

- Muhammad The Hagarene MassengerDocument35 pagesMuhammad The Hagarene MassengerWak HajiNo ratings yet

- Fariduddin Attar PDFDocument2 pagesFariduddin Attar PDFDarnese50% (2)

- Naskah MC Bahasa InggrisDocument2 pagesNaskah MC Bahasa Inggrisnesindahlia587No ratings yet

- Dua Al Mathur Grand Transmitted Supplication Shaykh Abdullah Daghestani 20200226Document12 pagesDua Al Mathur Grand Transmitted Supplication Shaykh Abdullah Daghestani 20200226Farah100% (1)

- DAFTAR UNDANGAN EKSTRA UPDATE 20 Okt 2019 Pukul 22.18Document12 pagesDAFTAR UNDANGAN EKSTRA UPDATE 20 Okt 2019 Pukul 22.18Pramusetya SuryandaruNo ratings yet