Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Prevalence of Chat Chewing in Butajira

Uploaded by

ifriqiyahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Prevalence of Chat Chewing in Butajira

Uploaded by

ifriqiyahCopyright:

Available Formats

A r l o P.

syrhiutr

Scund 1999: 100. 84-91 Printed in UK. AN rights resrrsed

A C T A PSYCHIATRICA SCANDINAVICA ISSN 0902-4441

The prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of khat chewing in Butajira, Ethiopia

Alem A, Kebede D, Kullgren G. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of khat chewing in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatrica Scand 1999: 100: 84-91. 0 Munksgaard 1999

A house-to-house survey was carried out in a rural Ethiopian community to determine the prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of khat use. A total of 10 468 adults were interviewed. Of these, 58% were female, and 740/0were Muslim. More than half of the study population (55.7%) reported lifetime khat chewing experience and the prevalence of current use was 50%. Among current chewers, 17.40/0reported taking khat on a daily basis; 16.1% of these were male and 3.4% were female. Various reasons were given for chewing khat; 80% of the chewers used it to gain a good level of concentration for prayer. Muslim religion, smoking and high educational level showed strong association with daily khat chewing. I

A. Alem, D. Kebede*, G. Kullgren3

Amanuel Psychiatric Hospital. Addis Ababa, Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and 3Department of Psychiatry. Ume3 University, UmeB, Sweden

Key words khat chewing, prevalence, ethnictty. Ethiopia Atalay Alem, Arnanuel Psychiatric Hospital. P 0 Box 1971, Addis Ababa. Ethiopia

Introduction

Khat (Catha edulis) is an evergreen plant that grows mainly in Ethiopia, Kenya, Yemen, and at high altitudes in South Africa and Madagascar. The plant is known by different names in different countries: chat in Ethiopia, qat in Yemen, mirra in Kenya and qaad orjaad in Somalia, but in most of the literature it is known as khat. In khat-growing countries, the chewing of khat leaves for social and psychological reasons has been practised for many centuries. Its use has gradually expanded to neighbouring countries and beyond through commercial routes. Recently, increasing numbers of immigrants have spread the practice to Europe and the United States (1). There is an indication that immigrants might be using more khat in Europe than in their country of origin (2). The origin of khat is not clear, but it is generally agreed that khat is native to Ethiopia and was first used there (3). Between the first and sixth centuries (AD), khat was introduced to Yemen where later the Danish botanist and physician Forsskal (1736-1763) gave the name Catha edulis to the plant growing on the mountain of A1.-Yaman (3). Terms such as Tea of the Arabs or Abyssinian Tea formerly used for khat indicate that dried

leaves of khat were boiled and used as modern tea is now (4). The Harar region of Ethiopia is universally believed to be the origin of khat use and, not surprisingly, people of Harar consider khat a treatment for all kinds of different ailments (5). The medical use of khat goes back to the time of Alexander the Great, who used khat to treat his soldiers for an unknown epidemic disease (5). Historically, khat has also been used as medicine to alleviate symptoms of melancholia and depression. Modern users report that chewing khat gives increased energy levels and alertness, improves self-esteem, creates a sensation of elation, enhances imaginative ability and the capacity to associate ideas, and improves the ability to communicate (6). For some, chewing khat is a method of increasing energy and elevating mood in order to improve their work performance. Khat is also considered a dietary requirement by some. It may also be used to suppress hunger when there is shortage of food. For many centuries the active ingredient in khat was not known. Now it has been discovered that the psycho-stimulant effect of khat is due to the alkaloid chemical ingredient cathinone present in the fresh leaves of the plant. Cathinones chemical structure is similar to amphetamine. The results of

84

Khat chewing in Butajira

various irz vivo and in vitro experiments indicate that the substance could be considered a natural amphetamine (7, 8). The effects of cathinone in animals correspond to those observed in khat-using humans. The pattern of dependence cathinone produces is also similar to that of amphetamine. Consequently, WHO has recommended that cathinone be put under international control and it is now included in the list of controlled drugs. Because of cathinones similarity to amphetamine, there is reason to believe that the effect of khat on health may be similar to that of amphetamine. The differing effects on health are mainly due to differences in dosage and mode of application (9). Compared to amphetamine, khat is less likely to cause tolerance perhaps because there are physical limits to the amount that can be chewed. Khat is said to cause persistent psychic dependence rather than physical dependence (10, 11). However, true withdrawal symptoms, such as profound lassitude, anergia, difficulty in initiating normal activity, and slight trembling, several days after ceasing to chew have been reported. Nightmares, often paranoid in nature of being attacked, strangled or followed, are also other symptoms of withdrawal. Most people chew khat in groups during special ceremonies intended to enhance social interaction or facilitate contact with Allah by Muslims. In fact, in some localities buildings and homes are architecturally designed to include rooms that comfortably accommodate khat ceremonies. Morghem and Rufat ( 12) describe khat chewing ceremonies as follows: the khat ceremonies conform to a specific pattern. Friends gather in the allocated room. They spread mattresses on the floor upon which they recline leaning against the wall with their elbows resting on pillows. Some prefer to keep a blaze of charcoal in the centre of the room to burn incense. Only tender khat leaves and stems are chewed, and the juice is swallowed. The residue accumulates in the mouth until the end of the session and the bolus makes a characteristic bulge in the cheek of the chewer. During the session, fluids like tea and soft drinks are consumed; often music is played. In such sessions a high level of social interaction is achieved and most important topics for discussion are reserved for such sessions, Individuals who regularly hold the ceremony strive to get the best out of every session. An average of two to three hours is spent on the khat ceremony every day by some regular users. Such parties are mostly attended by men and mixed parties with women are rare. Many observers have reported a negative impact on health and socio-economic conditions in communities where khat is used regularly (13). Almost all classes of people use khat in places where its use is endemic. However, the urban poor are believed to

be most negatively affected. Some estimate that as much as 85% of mens monthly income may be spent on khat in some communities (13). Some reports indicate that khat consumption has adverse consequences for married life. Spending money to maintain the habit and wasting time at the khat ceremonies lead to family neglect and, consequently, to divorce. In some cases deterioration of sexual activities and estrangement between spouses is also reported. In a Somali study, 18.8% of the male respondents reported improvement of sexual n reported performance after khat chewing, but 6 1Y that it caused impairment (13). Regular use of khat can reduce working hours and capacity for work when the substance is not used. This is believed to reduce the economic growth of a country (4). On the other hand, the economic benefit from the sale of khat is said to be high. A considerable amount of revenue is generated from khat export by countries that grow khat. There are several reports on unwanted physical and psychological effects among regular chewers of the substance. More cases of low birth weight and still birth among khat chewing mothers than among non-users has been reported (14). It has also been reported that khat addiction has a deleterious effect on semen parameters and deforms sperm cells ( 15). Gastritis, malnutrition, constipation, anorexia, spermatorrhea, arrhythmias, impotence, elevation of blood pressure, are among other physical effects reported in khat users (16, 17). Insomnia, anxiety, depression on cessation, tension, and various psychotic symptoms are also reported by different investigators (11). Until 1995, 16 cases of khatinduced psychoses have been reported in Europe and America among African and Arab immigrants ( 18). Paranoid state, schizophreniform psychosis, Capgras Fregoli syndrome, acute schizophrenia-like psychotic syndrome, and mania were the primary diagnoses given to the cases until relationships between the onsets or recurrences of symptoms and khat consumption were discovered (1 8-22). In two of the cases, homicide and combined homicide and suicide following consumption of khat were reported (19). In most of those cases, heavy khat consumption preceded the psychotic episodes. We recently reported a khat-related case that was admitted to Amanuel Mental Hospital from the central prison in Addis Ababa by court order for a sanity evaluation. He had repeatedly displayed violent behaviour following heavy khat consumption with spontaneous remission in a couple of days or weeks. During one such episode, he had violently killed his wife and his daughter and injured his cattle (23). It is also a familiar experience of the primary author of this paper to observe a high

85

Alem et al.

proportion of khat chewers among inpatients at Amanuel Mental Hospital. Khat use is legal in Ethiopia. Khat chewing has been a daily practice in many Ethiopian communities for many generations. The practice, with its alleged ill effects, is currently spreading throughout the country (24). In general, there is only a limited amount of data on khat chewing in Ethiopia. The two epidemiological studies available thus far are based on small samples of students (25, 26), which may not reflect the situation in communities. So far, no community-based study has been conducted in the country. We feel that such data are essential for policy issues, further studies and planning in health. We report here on the results of a survey conducted in a rural community as one of the important components of the general mental health survey.

Material and methods Study area

questions on problem drinking and suicide attempt were added to the SRQ. A few questions to enquire about income and cigarette smoking were included as well. The questions used for this study were the following: Have you ever chewed khat? (no/yes) If yes, how long have you chewed? (in years) Do you chew now? (no/yes) If yes, how often? If you are chewing daily, what time of day? (morning/day time/evening/if more than once, specify) (vi) What is the reason for you to chew khat? (for pleasure/to socialize/to prevent the withdrawal effect/to pass time/for prayer/other, specify) (vii) Do your small children also chew khat? (no/ Yes) (viii) If yes, at what age (in years) do they start? (less than 5/5-9/10-15) (ix) How do you get khat? (own f a r d b u y it/own farm and buying/other, specify) (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v)

The study was conducted in Butajira, one of the rural districts of Ethiopia. It is located 130 km south of Addis Ababa and is one of the most densely populated districts in the country. Although the areas major ethnic group is Gurage and the population is predominantly Muslim, there is also a minority of persons from diverse ethnic groups, and there is a substantial Orthodox Christian community. Butajira is the only major town in the area. The districts health needs are served by one health centre inside the town and two health stations and four health posts outside the town. The mainstay of the districts economy is farming; peppers and khat are the main cash crops. Kocho, a fibrous bread prepared from the stem of the false banana plant, is the staple diet. A rural health project was started in this district in 1986 as a collaborative research undertaking between the Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, and the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Ume& University, Sweden. The objectives of the project were to establish a demographic study base for research on essential health problems in a rural area and to develop and strengthen the research capacity and infrastructure for this purpose. Detailed descriptions of the base are reported elsewhere (27).

Instrument

Design

The design of the study is described elsewhere in detail (28). Briefly, 21 high school graduates were recruited from the town of Butajira to collect data. They were given three days training in interview techniques and how to complete the questionnaire. Initially, the questionnaire was pretested on 40 people from villages not included in the study. None of these individuals had any negative reactions to any of these questions. The survey was performed between November 1994 and January 1995.

Statistical analysis

The EPI-INFO version 5 computer program was used for data entry and preliminary analysis. Chisquare analysis was employed to compare intergroup distribution using SPSS version 7.

Results

This study was combined with a general mental health survey in the study base that used the Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) to assess mental distress (28). Nine questions for this study and other

The survey included 5259 houses where 12531 persons above the age of 15 resided. Fifteen per cent of these persons (n=1873) did not respond to the questionnaire. Individuals who were not found at home on three consecutive visits accounted for 91% of the non-respondent group. Nine per cent (n= 173) of the non-respondents failed to participate because of various personal reasons. Some of these individuals were prevented from responding because of physical or mental illnesses. From those who did

86

Khat chewing in Butajira

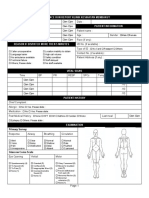

Table 1 Distribution of daily khat chewing according to socio demographic factors, stratified for sex

Variable Age 15-24 25-44 45-59 60+ Religion Christian Muslim Marital status Single Married Divorced Widowed Education Illiterate Elementary Secondary+ Ethnicity Gurage Others Income Income 1 Income 2 Income 3 Problem drinking No Yes Smoking No Mild Moderate Heavy Mental distress

Population n

Khat chewers n

Male chewers

~~

Female chewers

Statistics

Chi square

df

P-value

M+F=51 24 2997 4669 1732 1089 2668 7800 2527 681 1 254 876 8295 1514 651

8668 1800

<o

001

195 496 159 64

158 381 120 47 76 630 189 494 14 9 430 153 123 648 58 539 97 17 650 56 573 46 45 56 596 110 706

12 0 21 5 15 3 90 69 192 13 5 17 2 21 2 13 2 14 8 14 7 28 6 17 6 84 15 6 194 18 3 16 0 17 0 143 25 4 35 2 42 7 16 0 17 0 16 1

37 115 36 17 10 195 23 142 7 33 173 19 13 190 15 158 15 4 203 2 200 0 2 3 160 45 205

22 40 39 30

06 43

M=73 48 F = l l 40 M+F=13530 M = 9 2 19 F=48 34 M+F=20 67 M=1602 F=8 08 M+F=148 34 M = 5 5 10 F=4 70 M+F=59 09 M = 3 6 12 F=1644 M+F=4 88 M=4 93 F=O 93 M+F=20 36 M=O 22 F=O 01 M+F=386 27 M=125 65 F=48 77 M+F=3 10 M=O 42 F=O 91

<o 001 <o 01

<o 001 <o 001 <o 001 <o 001 <o

001 <O 05

86 825

212 636 21 42 603 122 136

838 73

20 36 34 41

32 40 57 38 14 35 25 39 34 36 33 00 50 0 30 0 33 38 34

<o 001 <o 001

ns

<o <o

001

(0 001

001 ns ns ns

7948 1047 196 10 083 385 10088 186 132 141 8642 1826 10 468

697 112 21 853 58 773 46 47 59 756 155 91 1

001 ns ns <o 001

<o

<o

<o

001 001

No Yes

Total

ns ns ns

not respond because of personal reasons, 13% (n-22) were severely mentally ill. One hundred and ninety questionnaires were found to be incomplete and were excluded from the analyses. The study population thus consisted of 10468 individuals. Over 50% were female, and there were more respondents between the ages of 25 and 44 than in the other age categories. The majority of the respondents belonged to the Gurage ethnic group, were Muslim, and had no formal education. Most were married. Income was divided into three levels based on the annual income of families in birr as follows: Income 1 < 1200, Income 2= 1200-6000, Income 3=6000+ (1 US$=6.5 birr). There were 1277 (1 2.2'%1) individuals who were not able to specify their income. Seventy-six per cent had an estimated annual income equivalent to or less than US$190.

More than half of the study population reported lifetime khat chewing experiences. Among these, the majority was male. The prevalence for current chewing in both sexes was 50% with a higher frequency among men (70%) compared to women (35%). The duration of khat use ranged from less than a year to 70 years. The median duration was 12 years. Among the current chewers, 17.4% (n=911) reported using the substance on a daily basis. A great majority (97%) of daily users reported chewing only once a day, and the rest reported chewing twice daily. Around noon is the preferred time of day for chewing. Most consumers (57.3%) buy their khat, and only 27% obtained the plant from their own farms. Various reasons for chewing khat were given. The majority (80.0%) reported that they used khat to obtain maximum concentration levels during prayer. Of these, 96% were Muslim.

Alem et al. Socializing or conformity with the norm was given as the main reason for khat use by 25% of the respondents, 12.1% used it to stabilize their emotions, 0.6% took it because of dependence and I .3%1 for concentration when studying, and for efficiency at work. Ten per cent (n=541) of the khat users reported that their small children also chewed khat. Of these, the majority (88.2%) reported that 10-15 years is the age at which children start chewing. Twelve people reported that even children under five chew khat. Detailed analysis of socio-demographic correlates was carried out only on those individuals who chewed khat on a daily basis (Table 1). Chi-square statistics are presented for both sexes combined and after stratification. Daily khat chewing yielded a significantly higher association with male than with female sex (chi-square 520.37; P<O.OOl). All variables were stratified for sex. Young adults and the middle-aged showed higher associations for daily chewing compared to adolescents. The highest percentage of daily chewers were between the ages of 25 and 44 years. Being Muslim was a significant predictor of daily khat chewing in both sexes. There is a significant association between high level of education and khat chewing among men only. The Gurage people were more likely to chew khat daily. This difference was statistically significant. There was an association between marital status and daily khat chewing; among men it was the divorced and among women, it was the widowed who were most likely to be khat chewers. People who smoked cigarettes were operationally classified into three groups based on the number of cigarettes they smoked daily, as follows: 1-3=mild, 4-9=moderate, and >9=heavy. Cigarette smoking showed a significantly higher association with khat chewing than non-smoking. Heavy smokers showed over a three-fold greater association than nonsmokers. Problem drinking was also associated with khat chewing, but not so when stratified for sex. There was no significant association between khat chewing and general mental distress. report on a study of 468 high school students in Yemen showed that 12% of the students were khat users. Ninety per cent of the students fathers and 60%) of their mothers were khat users. In the Democratic Republic of Yemen, in 1976, a group of health workers estimated that 50% of the adult male population indulged in khat chewing. In Somalia, in 1981 , it was estimated that about 75% of the men and 7710% of the women chewed khat regularly, and that khat use was increasing. In 1982, it was estimated by WHO visitors that 90% of the men and 10% of the women regularly chewed khat in Djibouti. In a randomly selected sample of general outpatient clinic attenders in Kenya, it was found that 29% were khat chewers and that only one of them was female (29). Our study indicates a lower prevalence of khat use than previous general estimates from Yemen, Djibouti and Somalia. However, there were fewer women who chewed khat reported in those countries than in our population. The 1981 estimate of 75% for men who chewed khat in Somalia is comparable to the results of our study. The differences between these estimates and our findings may be that figures from those countries were mere educated guesses rather than based on scientific studies. If our study had been done in the 1970s and the early 1980s, we may have obtained results similar to the estimates in those countries, particularly that of khat use by women. The emancipation of women, which has been one of the movements in Ethiopia for the last 20 years, may have increased the number of khat chewing women in Butajira. However, the prevalence of khat chewing among men is still twice as high as that of women in this study. This may be explained by the persisting cultural restriction on women against the use of such substances. The prevalence of khat chewing in Butajira is close to the prevalence (54.9%) reported among the Hargeisa community in Somalia (7), but lower than the prevalence of 64.9% among the Agaro Secondary School students (26) in south-western Ethiopia. The higher prevalence among the Agaro students may be due to a population composition that does not represent the general population. The student population in our study was very low (3%) and would not have a great impact on the results when seen together with the rest of the population. Similar studies among Mogadishu inhabitants in Somalia (7) and among students at Gondar College of Medical Sciences, Ethiopia (25) found a prevalence of 18.26% and 22.3%, respectively. The lower prevalence in these studies might be explained by relatively greater distances between those places and khat-growing areas.

Discussion

Epidemiological studies on khat use are rare. Baasher and Sadoun (4) reviewed the epidemiology of khat chewing in their paper presented at the International Conference on khat in Madagascar in 1983. According to their review, in 1972, a WHOsponsored mission to Yemen estimated that approximately 80% of the adult men in major cities and 90% of the men in khat-producing villages were regular khat chewers. The prevalence was estimated to be lower among women. Another

88

Khat chewing in Butajira

The significantly positive association between the Muslim religion and daily khat chewing is similar to the finding among Agaro students and to reports from elsewhere (30). Khat growing and the practice of chewing has traditionally been confined to the lowlands of Ethiopia where the Muslim population predominates and the habit could easily be passed from generation to generation, as evidently shown by the positive association of daily chewing and the Gurage ethnic group in this study. The custom of khat chewing in group prayer sessions by Muslims can also be one of the possible explanations for the difference. In this study, khat chewing was more frequent between the ages of 25 and 44 and less common after the age of 59. This finding is closer to the results of a study in Mogadishu (7) that reported a peak age of 2 0 4 0 and to a survey in Kenya ( 31) that reported a peak age of 2 1 4 0 . In our study, 10% of the respondents reported that small children chew khat with their parents. Most of these people (88.2%) reported that the age of onset of khat chewing is 10-15 years. The median age of onset reported by Agaro students was 14.6 years, and 16.4 years by Gondar students. This indicates that khat consumption starts during the teenage years, peaks during early adulthood, and declines after middle age. The young adult and middle-aged and the more educated groups who represent the most productive sections of the society are most affected by the khat chewing habit. Kalix authoritatively reviewed the negative health, socio-economic, and political effects of khat chewing in countries where the habit is widespread (6). His argument for the negative socio-economic effect was based on observations regarding time and money spent to maintain the habit. On the other hand, one might argue that moderate use of khat might improve performance and increase output of work because of its stimulant and fatigue-postponing effects. The increased association of its use with those who have higher educational attainment in this study and previous studies (7,25,26)might lead one to hypothesize that prior khat use might have enabled these individuals to progress in their education better than non-users. Therefore, simple observation may not allow us to discuss the negative or positive socio-economic impact of khat chewing on those societies where khat chewing is a common practice. However, taking all the evidence together one is inclined to say the negative effects of khat chewing outweigh possible positive effects. All users of khat in the Somali and Ethiopian studies mentioned above obtain it by purchasing. This includes students of the Agaro Secondary School. which is located in an area where khat is

commonly grown. Most chewers among our study population obtain the substance by buying it, whereas 27% of the chewers grew it themselves. This suggests that khat is a cash crop grown mainly for economic reasons. In fact, because khat is a drought-resistant plant, it does not require much effort to cultivate, and generates more income than other cash crops; farmers in khat-growing areas destroy other cash crops, such as coffee, and replace them with khat. In a study that compared the income levels of two khat-growing and non-khatgrowing communities in a district of Hararghe region in Ethiopia, it was shown that the mean income per family in the khat-growing community was 2704 birr compared to 875 birr in the non-khatgrowing community (32). The study also reported a greater ownership of modern commodities and facilities by the khat-growing community than by the non-khat-growing community. Khat was assessed as the source of 76.8% of income in the khat-growing community, while crops, milk, and fire-wood were the sources for 100% of the income in the non-khat-growing community. That study has also indicated the relative reluctance to grow essential crops and breed cattle in the khat-growing community. Such findings tempt one to compare khat growers with those who invest relatively little to grow and sell illicit drugs in order to make more money than those who work harder to produce essential products that contribute to their countrys development and the well-being of its citizens. The reasons given by our population for chewing khat were to enhance concentration during prayer and study, to improve social interaction, to elevate mood, and to avoid withdrawal symptoms. This finding is similar to previous reports (6). This indicates that khat has similar effects on users to that of amphetamine and other psycho-stimulants. Amongst our population, khat seems to be used more when people engage in higher level mental exercises, where alertness, concentration, high imaginative capacity and social interaction are required. Prayer and study are among the activities that require high concentration and imagination. The increase in khat use with increasing educational level could be explained in the same way. People with a high level of education are likely to be engaged with tasks that require imaginative thinking to a greater extent than those who are less educated. It might also be that the immense pressure of academic success at all levels (owing to fierce competition) tempts young people to use khat in the hope that it might increase their chances of being successful. However, there are no studies to show that khat increases intellectual performance. Many drivers in Ethiopia, long distance truck drivers in particular, are regular khat consumers. This group

89

Alem et al.

of people chew khat to gain the maximum alertness and concentration for their demanding job. The most frequently stated reason for chewing khat was to increase concentration during prayer. This may be explained by the predominance of Muslims among the study population, reflected in the fact that 96% of those who gave this reason are Muslims. In this study, 0.6% (n=29) reported that they continue to chew khat because of withdrawal symptoms. This suggests that khat hardly causes physical dependence. The strong association of daily khat chewing with cigarette smoking in this study is in line with findings from other studies ( 3 3 ) . Khat chewers are believed to take alcohol to break the stimulant effect of khat after long hours of stimulation. The expression used for such a practice in one of the Ethiopian languages, mirkana chahsi, connotes breaking the effect. Contrary to findings in that study, however, there was no association between daily khat chewing and problem drinking in our study. There seemed to be an overall difference in problem drinking between daily chewers and nonchewers, but when stratified for sex this was no longer the case. The fact that the study by Omolo and Dhadphale was not a community sample and that almost all of their subjects were male might explain the difference in the results. There was no significant difference in the habit of khat chewing between high and low scorers on a mental distress scale measured by the SRQ. Dhadphale and Omolo (34), in Kenya, reported that the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity was the same among moderate chewers and non-chewers. However, they found a higher prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among excessive chewers than among non-chewers. Since the attempt to quantify the amount of consumption was not successful in our study, it was not possible to show the dose-related effect of khat consumption on mental health. In conclusion, this study has shown that the khat chewing habit affects a majority of the adult population in the Butajira district. The section most affected by khat chewing seems to comprise the most educated and the most productive age group of the community. Although the methods employed in measuring mental disorders in this survey were not very specific, general mental distress, as measured by the SRQ, has not been shown to be associated with khat chewing. We recommend an appropriately designed study to look into the effect of khat chewing on the socioeconomy and health of a community where its use is very common.

90

Acknowledgements

The study was financed by the Swedish Medical Research Council and the Swedish Agency for Research Co-operation with Developing Countries through the Department of Psychiatry, Umei University. Material assistance obtained from the Department of Community Health, Addis Ababa University and Amanuel Hospital is also acknowledged. We would like to thank Drs. Ayana Yeneabat, Abeba Bekele and Ato Teferi Gedif for assisting us in supervising the data collection process. We thank Professor R. Giel, Drs. Barbara Singleton, Robert Kohn and Matthew Hotopf for their comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. We also thank all the data collectors and the study participants who kindly gave us the necessary information.

References

P,IGRASSSI MC, BOTAN AA, ASSEYR AF, PAOLI E. 1. N E N C I N 2. 3. Khat chewing spread to the Somali community in Rome. Drug Alcohol Depend 1988: 23: 255-258. GRIFFITHS P, GOSSIP M, WICIKENDEN S, DUNWOKH J, HARRIS K, LLOYD C. A transcultural pattern of drug use: qat (khat) in the UK. Br J Psychiatry 1997: 170: 281 284. ASEFFAM . Socio-economic aspects of khat in the Harrarghe administrative region, Ethiopia. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17-21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. BAASHER T, SADOUNR. Epidemiology of khat. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17-21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. BALINT GA, GEBREKIDAN H, BALINT EE. Cuthu edulis, an international socio-medical problem with considerable pharmacological implications. East Afr Med J 1991: 68: 555-561. KALIX P. Khat: scientific knowledge and policy issues. Br J Addict 1987: 82: 47-53. ELMI AS. Khat consumption and problems in Somalia. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17-21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. KALIX P. The pharmacology of khat. Gen Pharmacol 1984: 15: 179-187. SCHECHTER MD, ROSECRANS JA, GLENNON RA. Comparison of behavioural effects of cathinone, amphetamine and apomorphine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1984: 20: 181-184. KALIX P. Khat: a plant with amphetamine effects. J Subst Abuse Treat 1988: 5: 163-169. HALBACH H. Medical aspects of chewing khat leaves. Bull World Health Organ 1972: 47: 21L29. MORGHEM MM, RUFAT MI. Cultivation and chewing of khat in the Yemen Arab Republic. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17-21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. GETAJIUN A, KRIKORIAN AD. The economic and social importance of khat and suggested research and services. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17-21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. ERIKSSON BM, GHANI NA, KRISTIANSSON B. Khat chewing during pregnancy: effect upon the off-spring and some characteristics of the chewers. East Afr Med J 1991: 68: 106-110. EL-SHOURA SM, A B D ~ AZIL L M, ALI ME, et al. Deleterious effects of khat addiction on sperm parameters and sperm ultra-structure. Hum Reprod 1995: 10: 2295-2300.

4.

5.

6. 7. 8. 9.

10. 11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

Khat chewing in Butajira

16. KENNEDY J, TEAGUE J, RROKAW W, COONEY E. A medical evaluation of the use of qat in North Yemen. SOCSci Med 1983: 17: 783-793. 17. MEKASHA A. The clinical effects of khat (Catha edulis Forsk): Proceedings of the International Symposium on Khat, December 15 1984, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 18. YOUSEF G, HUQZ, LAMBERT T. Khat chewing as a cause of psychosis. Br J Hosp Med 1995: 99: 322-326. 19. PANTELIS C, HINDLER CG, TAYLOR JC. Use and abuse of khat (Catha edulis): a review of the distribution, pharmacology, side effects and a description of psychosis attributed to khat chewing. Pharmacol Med 1989: 19: 657-668. AJ, CASTELANI FS. A manic like psychosis due 20. GIANNINI to khat (Catha edulis Forsk.). J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1982: 19: 455459. 21. GOUGH SP, COOKSON IB. Khat induced schizophreniform psychosis in the UK (letter). Lancet 1984: 1: 455. 22. DHADPHPALE M, MENGECH HNK, CHEGE SW. Miraa (Catha edulis) as a cause of psychosis. East Afr Med J 1981: 58: 130--135. T. Khat induced psychosis and its 23. ALEMA, SHIBBE medico-legal implication: a case report. Ethiop Med J 1997: 35: 137-141. 24. GEBRE SELASSIE S, GEBRE A. Rapid assessment of the situation of drug and substance abuse in selected urban areas in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Health, 1995. 25. ZEIN AZ. Poly drug abuse among Ethiopian University students with particular reference to khat (Catha edulis). Am J Trop Med Hyg 1988: 91: 1-5. 26. ADUGNA F, JIRAC, MOILAT. Khat chewing among Agaro Secondary School students, South Western Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 1994: 32: 161 166. 27. ALEM A, JACOBSSON L, ARAYA M, KEBEDE D, KULLGREN G. How are mental disorders seen and where is help sought in a rural Ethiopian community? A key informant study in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999: 100 (Suppl): 4 0 4 7 . G, JACOBSSON L, 28. ALEMA, KEBEDE D, WOLDESEMIAT KULLGREN G. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of mental distress in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999: 100 (Suppl): 48-55. 29. OMOLO OE, DHADPHALE M. Alcohol use among khat (Catha edulis) chewers in Kenya. Br J Addiction 1987: 82: 97-99. 30. MIATAI CK. Epidemiology. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17-21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. 31. MIATAI CK. Country report; Kenya. Proceedings of the International Conference on Khat, January 17--21 1983, Antananarivo, Madagascar. 32. SEYOUM E, KIDANE Y, GERRU H, SEVENHUSEN G. Preliminary study of income and nutritional status indicators in two Ethiopian communities. Food Nutr Bull 1986: 8: 3741. 33. OMOLO OE, DHADPHALE M. Prevalence of khat chewers among primary health clinic attenders in Kenya. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987: 75: 318-320. 34. DHADPHALE M, OMOLO OE. Psychiatric morbidity among khat chewers. East Afr Med J 1988: 65: 355-359.

~

91

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Virginity in EthiopiaDocument10 pagesVirginity in EthiopiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Tribes of IndiaDocument2 pagesTribes of IndiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Witch Sacrifice in IndiaDocument8 pagesWitch Sacrifice in IndiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- The AnthropogeneDocument3 pagesThe AnthropogeneifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Traditional Perceptions and Treatment of Mental Illness in EthiopiaDocument7 pagesTraditional Perceptions and Treatment of Mental Illness in EthiopiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- The Prehistory of Psychiatry in EthiopiaDocument3 pagesThe Prehistory of Psychiatry in EthiopiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- The Australian PygmieDocument21 pagesThe Australian Pygmieifriqiyah100% (2)

- Red Sea Trade and TravelDocument36 pagesRed Sea Trade and TravelifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Sabean ExchangeDocument12 pagesSabean ExchangeifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- The Jesus PuzzleDocument24 pagesThe Jesus PuzzleifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- The Grazzani MassacreDocument5 pagesThe Grazzani MassacreifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Poverty, Migration and Sex Work Youth Transitions in EthiopiaDocument9 pagesPoverty, Migration and Sex Work Youth Transitions in EthiopiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Israeli Ethiopian Mothers Perceptions of Their Children S Mild MDocument231 pagesIsraeli Ethiopian Mothers Perceptions of Their Children S Mild MifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Lij EyasuDocument1 pageLij Eyasuifriqiyah0% (1)

- Mass Eco-System ExtinctionDocument13 pagesMass Eco-System ExtinctionifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Male Circumcision - A Legal AffrontDocument48 pagesMale Circumcision - A Legal AffrontifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Making Exceptions For EthiopiaDocument3 pagesMaking Exceptions For EthiopiaifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Kunama Ethnic CleansingDocument2 pagesKunama Ethnic CleansingifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Klein Sexual Orientation GridDocument1 pageKlein Sexual Orientation GridifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- How Whites Use Asians To Further Anti-BlackDocument5 pagesHow Whites Use Asians To Further Anti-BlackifriqiyahNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- TIMO Final 2020-2021 P3Document5 pagesTIMO Final 2020-2021 P3An Nguyen100% (2)

- Duavent Drug Study - CunadoDocument3 pagesDuavent Drug Study - CunadoLexa Moreene Cu�adoNo ratings yet

- What Is TranslationDocument3 pagesWhat Is TranslationSanskriti MehtaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation TemplateDocument3 pagesEvaluation Templateapi-308795752No ratings yet

- An Exploration of The Ethno-Medicinal Practices Among Traditional Healers in Southwest Cebu, PhilippinesDocument7 pagesAn Exploration of The Ethno-Medicinal Practices Among Traditional Healers in Southwest Cebu, PhilippinesleecubongNo ratings yet

- 2021-03 Trophy LagerDocument11 pages2021-03 Trophy LagerAderayo OnipedeNo ratings yet

- DN Cross Cutting IssuesDocument22 pagesDN Cross Cutting Issuesfatmama7031No ratings yet

- Borang Ambulans CallDocument2 pagesBorang Ambulans Callleo89azman100% (1)

- Role of Losses in Design of DC Cable For Solar PV ApplicationsDocument5 pagesRole of Losses in Design of DC Cable For Solar PV ApplicationsMaulidia HidayahNo ratings yet

- 8.ZXSDR B8200 (L200) Principle and Hardware Structure Training Manual-45Document45 pages8.ZXSDR B8200 (L200) Principle and Hardware Structure Training Manual-45mehdi_mehdiNo ratings yet

- LEIA Home Lifts Guide FNLDocument5 pagesLEIA Home Lifts Guide FNLTejinder SinghNo ratings yet

- AnticyclonesDocument5 pagesAnticyclonescicileanaNo ratings yet

- Jesus Prayer-JoinerDocument13 pagesJesus Prayer-Joinersleepknot_maggotNo ratings yet

- Dalasa Jibat MijenaDocument24 pagesDalasa Jibat MijenaBelex ManNo ratings yet

- Monkey Says, Monkey Does Security andDocument11 pagesMonkey Says, Monkey Does Security andNudeNo ratings yet

- Global Geo Reviewer MidtermDocument29 pagesGlobal Geo Reviewer Midtermbusinesslangto5No ratings yet

- 05 x05 Standard Costing & Variance AnalysisDocument27 pages05 x05 Standard Costing & Variance AnalysisMary April MasbangNo ratings yet

- Project ManagementDocument11 pagesProject ManagementBonaventure NzeyimanaNo ratings yet

- PhraseologyDocument14 pagesPhraseologyiasminakhtar100% (1)

- Chapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDocument63 pagesChapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDr. Shuva GhoshNo ratings yet

- 2009 2011 DS Manual - Club Car (001-061)Document61 pages2009 2011 DS Manual - Club Car (001-061)misaNo ratings yet

- Hole CapacityDocument2 pagesHole CapacityAbdul Hameed OmarNo ratings yet

- Carriage RequirementsDocument63 pagesCarriage RequirementsFred GrosfilerNo ratings yet

- Spesifikasi PM710Document73 pagesSpesifikasi PM710Phan'iphan'No ratings yet

- II 2022 06 Baena-Rojas CanoDocument11 pagesII 2022 06 Baena-Rojas CanoSebastian GaonaNo ratings yet

- Benevisión N15 Mindray Service ManualDocument123 pagesBenevisión N15 Mindray Service ManualSulay Avila LlanosNo ratings yet

- Checklist & Guideline ISO 22000Document14 pagesChecklist & Guideline ISO 22000Documentos Tecnicos75% (4)

- Sba 2Document29 pagesSba 2api-377332228No ratings yet

- Roleplayer: The Accused Enchanted ItemsDocument68 pagesRoleplayer: The Accused Enchanted ItemsBarbie Turic100% (1)

- Residual Power Series Method For Obstacle Boundary Value ProblemsDocument5 pagesResidual Power Series Method For Obstacle Boundary Value ProblemsSayiqa JabeenNo ratings yet