Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Motorola University and Higher Education - The Exception That Proves The Rule

Uploaded by

ChewuBGDOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Motorola University and Higher Education - The Exception That Proves The Rule

Uploaded by

ChewuBGDCopyright:

Available Formats

Motorola University and higher education: the exception that proves the rule?

Part of the so-called e-education bubble and wider dotcom enthusiasm, the boom i n corporate universities in the 1990s prompted speculation that this appropriation of higher education nomenclature might spark some form of competition between corporate and conventi onal universities. As it turned out, the vast majority of corporate universities have remained exclusively focused on the development of in-house staff, that is, very much sti cking to the remit of the historical company training department prior to this latest round of re-b randing. That said, a recent announcement from a corporate university pioneer, Motorola University, is a reminder that not every corporate university has conformed to this pattern. Motorola cont inues to pursue greater ambitions as an outward-facing training provider, and has enlisted conve ntional universities as partners in this process. What is Motorola University in 2003, a nd how does it relate to the higher education sector? Motorola University (MU) is the education and training arm of Motorola Inc., the US telecommunications giant. Its origins may be traced back as far as 1981 when the Motorola Training and Education Centre was founded. At this stage the centre was intended to serve the in-house training needs of the corporation. Motorola expanded its training opera tions with the opening of the Galvin Centre for Continuing Education (Schaumburg, Illinois) in 1986 and the Singapore Training Design Centre in 1989. Motorola's intentions were to build a company-wide quality culture that would promote high internal standards and develop employee skills, translating into overall increased profitability. In 1986 the Six Sigma system w as created by a Motorola engineer, and soon became the company-mandated system of performance evaluation and improvement. Some argue that in-house adoption of the system (by re-focusing the business and emphasising quality improvement) saved the company from its pre dicament of rapid loss of market share to Japan during the 1980s. The Six Sigma system has g rown from an in-house tool to an internationally marketed brand available to all interested c ompanies. Now MU claims to serve 100 companies in 24 countries, ranging from Brazil and Mexico to China and Singapore. Some of the advertised companies practising the Six Sigma system are giants such as General Electric, Bombardier, and Lockheed Martin. Six Sigma programs are typically short (two days to four weeks) and company tail ored, offering both certificate and non-certificate options. Programs offered include 'Leadersh

ip Jumpstart' (two days for senior executives to bring the Six Sigma theory into practice in t heir business), 'Champion Training' (two days for the Six Sigma review representative at the com pany), 'Onsite Black and Green Belt Training' (20 and 5 day certification and training in basic to advanced theory of Six Sigma), and 'Expert Project Coaching and Mentoring' (designed for meeting short term campaign objectives within the Six Sigma system). Most recently MU has deve loped an online 'E-foundations Training' course (2-4 hours) that allows more flexibility in time and delivery of the Six Sigma curriculum. Completion of the Black Belt is a prerequisite to b ecoming a trainer of MU's Six Sigma. On an international scale MU is particularly well positioned to expand in Asia. Aside from the claimed core benefits of increased efficiency and profit, another advantage appe ars to be the longer-term value of MU certification. In an increasingly competitive business e nvironment, for both local and foreign firms, the MU brand has become a form of quality assuranc e adopted in the expectation that it may inspire confidence in investors. Some proponents of the MU product have likened it to the ISO's quality assurance system in this respect. MU's Asia n clients include banks such as HSBC, Overseas Chinese Banking Corporation, Scope International, a nd Deutsche Bank and government organisations such as Nanjing Education Committee a nd the National Productivity Council.

While MU includes "educational institutions" among its clients, it does not publ ish any details. However, there are known instances of conventional universities partnering with MU to market the Six Sigma system. One example is Kent State University, the second-largest p ublic university in Ohio, USA. The Stark Campus Office of Corporate and Community Serv ices is advertised as providing the "Resources of a major university coupled with expert ise in organizational and professional training and development." As an official MU Bus iness Partner, the staff in this office of the university will now be authorised to train and c ertify Six Sigma. Kent State has been actively involved in training, professional development, and prov iding research services to the Ohio business community over the past 15 years, and views the pa rtnership with MU as a useful extension of this. The partnership with MU is focused on Ohio and neighbouring states (MU headquarters are in nearby Chicago, Illinois), but is intriguing inso far as it involves a conventional university offering provision from a corporate university. (Motorol a itself has a range of research and development partnerships with universities worldwide). The potential for expansion of MU is particularly evident in China. MU China was established in 1993, with the goal of training both internal staff and the greater Chinese busi ness community. Having forged partnerships with 21 Chinese higher education institutions (includ ing well-known Beijing University, Tsinghua University, and Nankai University), MU China now of fer 130 courses and can call on over 200 instructors (including Motorola China's senior management). Motorola's expansion of strategic alliances in government, industry, and academi a is facilitated by their corporate university marketing. Motorola Senior Vice President and Dire ctor of Motorola University Sandy Ogg states that Motorola wants to "change from a pure corporate university which previously we called a training center, to a strategic partner of our cust omers, suppliers, partners in China and the rest of the Asia Pacific region." With China's recent accession to the WTO, Motorola has taken advantage of the desire of Chinese companies to prove an d distinguish themselves in an increasingly competitive and globalised environment . The corporate university in this case becomes another product to offer, separate fro m but to the benefit of the core business. Another interesting higher education partnership i nvolves MU operating as Chinese partner for University of Buffalo's EMBA programme. To this extent, Motorola University is clearly more than in-house training. Rath er it is an attempt to turn a distinctive approach to business into a brand that can be packaged and sold to the benefit of the company's credibility, partnering scope, and end profit. The prim

ary customer base and all cited success stories are from large corporations. Whether the prin ciples involved in the Six Sigma system would work for a smaller company remains to be seen. Sma ller businesses have not joined in to date due in large part to the costs of training and slow return on investment. GE spent US$200 million on Six Sigma in 1996 and posted savings o f only US$170 million. By the next year it saved US$700 million by spending US$380 mill ion, but the early losses are something that smaller companies cannot afford to risk. MU's pa rtnerships with what are essentially peer firms is also a matter of the company being able to re fer to itself as an appropriate model of successful development. That said, operating through establ ished partners (which tend to have extensive supplier and partner bases) does open up new marke ts for MU that would otherwise involve considerable marketing and set-up costs. Obviously to some extent just another business fashion, like re-engineering and TQM before it, corporate universities nonetheless remain a prominent feature of the landscape. Given longstanding criticism of graduate employability among some sectors of the busin ess community, some speculated that corporate universities might challenge their con ventional forebears, if not for the core business of undergraduate teaching, then at least the lucrative area of corporate development so central to business schools. While there is little e vidence of this to date, continued use of university title will ensure that higher education pays t he phenomenon more attention than it perhaps deserves. Most large firms have maintained a stro ng track record of partnering with conventional universities as a core element of any corporate university, and very few have got to the point where an outward-facing operation makes sense. Wh ile many companies could claim expertise in general good business practice that others mi ght find useful, few regard this as a useful addition to the core business. England's proposals t o open up degree-awarding powers and 'official' university title to private companies may generate new possibilities for the corporate university, but any dramatic interest is unlikel y. Overall, Motorola University is something of an exception and is likely to remain so. Nonetheless, its partnerships with conventional universities involve intriguing role-reversals, and arguably a mount to a healthy knowledge partnership between company and university.

You might also like

- Weemss Book Organizing Events On A Zero Budget PDFDocument62 pagesWeemss Book Organizing Events On A Zero Budget PDFChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Xge 0000030Document9 pagesXge 0000030ChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Facebook Contests and Promotions PDFDocument42 pagesFacebook Contests and Promotions PDFChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Edelman and The Rise of Public RelationsDocument127 pagesEdelman and The Rise of Public RelationsEdelman100% (11)

- Adr Negotiating ModelsDocument16 pagesAdr Negotiating ModelsChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Presentation Elevation v11Document81 pagesPresentation Elevation v11ChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Don Draper Is Dead FinalDocument25 pagesDon Draper Is Dead FinalChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Abcs of Inbound MarketingDocument34 pagesAbcs of Inbound MarketingChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- Motorola Case StudyDocument18 pagesMotorola Case StudyChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- WSJ Whitehouse ArticleDocument7 pagesWSJ Whitehouse ArticleChewuBGDNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Instructor's Manual for Multivariate Data AnalysisDocument18 pagesInstructor's Manual for Multivariate Data AnalysisyonpurbaNo ratings yet

- At, On and in (Time) - English Grammar Today - Cambridge DictionaryDocument7 pagesAt, On and in (Time) - English Grammar Today - Cambridge DictionaryKo JiroNo ratings yet

- 3RD Quarter Numeracy TestDocument4 pages3RD Quarter Numeracy TestJennyfer TangkibNo ratings yet

- Music 10 Q2 Week 1 DLLDocument37 pagesMusic 10 Q2 Week 1 DLLNorralyn NarioNo ratings yet

- Format - 5 Student DiaryDocument37 pagesFormat - 5 Student DiaryAbhijeetNo ratings yet

- M4 - Post Task: Ramboyong, Yarrah Ishika G. Dent - 1BDocument8 pagesM4 - Post Task: Ramboyong, Yarrah Ishika G. Dent - 1BAlyanna Elisse VergaraNo ratings yet

- New Year New Life by Athhony RobbinsDocument6 pagesNew Year New Life by Athhony RobbinsTygas100% (1)

- Task-Based Speaking ActivitiesDocument11 pagesTask-Based Speaking ActivitiesJaypee de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Lawrentian: Lawrence Works To Preserve Historic Teakwood RoomDocument12 pagesLawrentian: Lawrence Works To Preserve Historic Teakwood RoomThe LawrentianNo ratings yet

- FFDC FFA Fundamentals DatasheetDocument2 pagesFFDC FFA Fundamentals DatasheetSonal JainNo ratings yet

- Pankaj CVDocument3 pagesPankaj CVkumar MukeshNo ratings yet

- Pyc4807 Assignment 3 FinalDocument19 pagesPyc4807 Assignment 3 FinalTiffany Smith100% (1)

- Homeroom Guidance Program Activities PDF FreeDocument2 pagesHomeroom Guidance Program Activities PDF FreeAngelica TaerNo ratings yet

- Psihologia Sociala ArticolDocument71 pagesPsihologia Sociala ArticolLiana Maria DrileaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Jun 03, 2023Document12 pagesAdobe Scan Jun 03, 2023BeastBiasNo ratings yet

- Motivation LetterSocialDocument2 pagesMotivation LetterSocialIrfan Rahadian SudiyanaNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Volunteering at International Sport EventsDocument17 pagesChallenges of Volunteering at International Sport EventsAulianyJulistaNo ratings yet

- ReflexologyDocument6 pagesReflexologyapi-327900432No ratings yet

- Obe CSC 139Document5 pagesObe CSC 139Do Min JoonNo ratings yet

- Gap Between Theory and Practice in The NursingDocument7 pagesGap Between Theory and Practice in The NursingMark Jefferson LunaNo ratings yet

- MC Research Module 3Document8 pagesMC Research Module 3payno gelacioNo ratings yet

- Singing Game Music Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSinging Game Music Lesson Planapi-491297297No ratings yet

- Uniform Circular MotionDocument10 pagesUniform Circular MotionAndre YunusNo ratings yet

- Plato's Theory of Imitationalism in ArtDocument10 pagesPlato's Theory of Imitationalism in ArtKath StuffsNo ratings yet

- Sophie Reichelt Teaching Resume 2016Document4 pagesSophie Reichelt Teaching Resume 2016api-297783028No ratings yet

- 2 Field Study Activities 7Document13 pages2 Field Study Activities 7Dionisia Rosario CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Aldharizma - An Analysis of 101 Activities For Teaching Creativity and Problem Solving by Arthur BDocument13 pagesAldharizma - An Analysis of 101 Activities For Teaching Creativity and Problem Solving by Arthur BInd17 KhairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Grade 7 English Lesson on Analogy, Linear and Non-Linear TextDocument6 pagesPhilippine Grade 7 English Lesson on Analogy, Linear and Non-Linear TextJoshua Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Learning Theories FinalDocument5 pagesLearning Theories FinalJeo CapianNo ratings yet

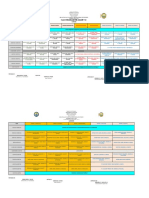

- Class Program For Grade 7-10: Grade 7 (Hope) Grade 7 (Love)Document2 pagesClass Program For Grade 7-10: Grade 7 (Hope) Grade 7 (Love)Mary Neol HijaponNo ratings yet