Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lessons From Temptation Island A Reality Television Content Analysis

Uploaded by

Tyler HallOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lessons From Temptation Island A Reality Television Content Analysis

Uploaded by

Tyler HallCopyright:

Available Formats

Lessons 1

Lessons from Temptation Island: A Reality Television Content Analysis

Sara E. Booker

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in General Psychology Department of Psychology

Central Connecticut State University New Britain, Connecticut

December 2004 Thesis Advisor Dr. Bradley M. Waite Department of Psychology

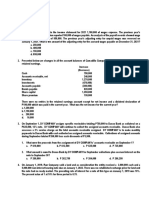

Lessons 2 Abstract The popular press has criticized reality television, for the most part, suggesting that it appeals to the basest of human fascinations. Reality television has been described as brimming with sex and gender stereotypes. Critics also have suggested that the genre thrives on putting real people in humiliating or degrading situations. What limited discussion is found in the psychological literature suggests that from a social learning perspective, the real people factor of reality television may make the characters more salient as social learning models. Viewers may in turn be more inclined to form opinions about real world norms from such shows. This study analyzed the content of the five most popular (according to Nielson ratings) reality television programs, and recorded the frequency of the behaviors mentioned most often by the critics: humiliation, violence and aggression, sex, and gender stereotyping. This study also analyzed the occurrence of such behaviors on a per character and per show basis. The five most popular scripted comedies and scripted dramas were also analyzed for content using the same methodology so that the results could be compared. Multivariate and univariate

analyses of variance were conducted. Results showed that reality television programs and scripted comedies contained significantly more humiliation per character than scripted dramas, but that scripted dramas contained significantly more violence and aggression per character than reality television programs or scripted comedies. Scripted comedies contained significantly more sex on both a per character and per show basis than reality television programs and scripted dramas. None of the three types of shows contained significantly more gender stereotyping than the others. The analyses

Lessons 3 also revealed that the mean scores for humiliation, as compared to the other behavior categories studied tended to be high. Demographic analyses for gender and age were conducted using two-way between subjects analyses of variance. It was found that there was no significant difference in gender (number of men versus women) or in age (older versus younger age groups) among different show types.

Lessons 4 Lessons From Temptation Island: A Reality Television Content Analysis

Table of Contents Abstract.2 Introduction ..7 The History of Reality Television.7 The Criticism of Reality Television..10 Why it is Important to Study Reality Television..13 Humiliation...17 Violence and Aggression..19 Sex.22 Gender Stereotypes24 Hypotheses27 Primary Hypotheses..27 Secondary Hypotheses..28 Method..29 Sample..29 Raters29 Coded Behaviors..29 Humiliation..30 Violence and Aggression.30 Implicit Sex..30

Lessons 5 Explicit Sex..30 Objectification..30 Dominance31 Subservience.31 Aggression with Sexuality31 Superordinate Variables32 Coding Sheet.....32 Procedure..34 Results .....35 Unit of Analysis...35 Preliminary Analyses...35 Per Character Analyses36 Per Show Analyses..37 Demographic Analyses38 Discussion38 Table 1.48 Table 2.49 Table 3....50 Table 4....51 Table 552 Table 653 Table 754

Lessons 6 Table 855 Table 956 Table 10..57 Table 11.58 Table 12.59 Table 13.60 Table 14.61 Table 15.62 Table 16.63 Table 17.64 Table 18.65 Table 19.66 Table 20.67 References.68 Appendix 176 Appendix 278 Biographical Note.81

Lessons 7 Lessons From Temptation Island: A Reality Television Content Analysis In his book Modern Times, Modern Places, which analyzes the transformation of art through the radical modernity movement of the twentieth century, author Peter Conrad (1999), speaks of a dismaying affinity between modern times and a more primeval era (p.13). Lately this idea has been tossed about in more casual terms before the water cooler, as conversation regarding what happened on last nights episode of the reality television program Joe Millionaire often takes on an air of pseudo-philosophical debate about the state of our society, based on what we find entertaining. The end of western civilization, according to many critics and average Joes alike, has arrived; at least it has on television. The latest culprit in this mass genocide of taste and morality in modern entertainment, according to the popular press, is reality television. In this new world, new millennium, post-September 11th era of cultural analysis, entertainment is often named by the disenchanted to be among what we value most in our media-saturated society (Pipher, 1998, p. 12). Like the advent of rock and roll, the pornographic cinema, and the talk show before it, the reality television format seems to be the latest trend on the entertainment chronology to incite such apocalyptic discussion. The History of Reality Television So just what is reality television? A reality television program, also known as a non-scripted program, is one in which there ostensibly is no traditional script (see Appendix 1 for examples). The scenarios that make up reality television programs, are to

Lessons 8 have occurred organically or with a minimal amount of contrivance from the producers, writers, and other members of the relatively limited creative team. A reality television program is supposed to be devoid of acting, choosing instead to capture the true triumphs and tribulations of real people (e.g. The Real World, Big Brother) or exhibitionistic celebrities (e.g. The Osbornes, The Simple Life). Sometimes the subjects of reality television shows are not people at all, but naturally occurring spectacle-level events such as police chases and airplane crashes (e.g. You Gotta See This, Worlds Wildest Police Chases). The first American show popularly dubbed a reality show was Music Televisions (MTV) The Real World, although retrospect has resulted in reluctant classic shows like Candid Camera to be included in this instantly infamous genre. These shows did not really begin to boom until 1999 when Survivor stole the ratings from scripted program staples of Nielsen lists like ER and Friends. (Note: Nielsen ratings lists rank the popularity of television shows on a national scale by number of viewers. Nielsen is the recognized television ratings service leader (About Nielsen Media Research, 2004). With a supposed writer and actors strike looming on the horizon the following year (Sparks & Miller, 2002), the reality format was eagerly courted by fearful networks. The overhead for crew and production (is) minimal (Rome, 2002, para. 2). The format is inexpensive. Traditional actors are replaced with real people. There is little need for writers, as scandalous or sensationalized scenarios are caught on tape, edited to the producer's whims and sold as a cheap substitute for a well-written script (Sussman, 2003, para. 3).

Lessons 9 Producers soon began to openly (create) scenarios they felt the audience wanted to see (Rome, 2002, para. 2). One very popular example of this format is the reality television program in which people are voted out of a competition by fellow competitors (e.g. Survivor, Big Brother). A successful derivation of this concept has been the dating reality show, such as the overtly sexual Shipmates or Elimidate in which fellow suitors are eliminated one by one from the running. Another common theme within the reality television family that critics lament is the gross-out segment where competitors on Fear Factor eat worms, for example, or the pranksters from Jackass write a gag with copious references to the restroom. Successful shows served as templates and a veritable boom of reality shows has ensued. During February 2003 a television anomaly occurred. The perennially fourthplaced Fox Television Network (Fox) topped the Nielson ratings, thanks to none other than reality television. Because of the success of Joe Millionaire and American Idol, Fox achieved an unprecedented first-place finish among adults younger than 50 (Lowry, 2003, para. 2). While Foxs dramas, like the acclaimed 24 concurrently suffered a decline in audience numbers, reality television programs such as Joe Millionaire and American Idol enjoyed a surge in popularity. The premiere episode of Joe Millionaire attracted an audience of over 20 million people. During the month of January 2003, reality television programs accounted for 85% of the most valuable broadcasting (for advertisers) in the United States (Cafferty, 2003). Advertisers are scurrying to take advantage of this public demand, as these shows are especially popular with the coveted 18 to 49 year old market.

Lessons 10 The Criticism of Reality Television The explosive popularity of reality programs (e.g. Survivor, Cops, Fear Factor, etc.) has served as a catalyst for a torrent of criticism and speculation on how low the producers of such shows will go. The content on television as of late according to one Boston Herald editorial has, predictably, reached bottom and started to dig (Rome, 2002 para. 2). Cultural analysts seem to look at reality television programs as entertaining (or disturbing) microcosms representing all that is wrong with the modern world. With the surging popularity of reality television, the popular press has lamented the loss of television programs that portrayed characters in comedic or dramatic situations. Now many such shows have been supplanted by programs featuring real people in humiliating, degrading situations. Reality television programs are charged as being crafted for the sole purpose of attracting ratings. According to many critics they lack artistic merit and have little or no redeeming social value. They appeal to the basest aspects of human nature, the same impulses that cause one to gawk, slack-jawed at a train wreck. Many feature people in humiliating and degrading scenarios. People on these shows lose competitions and get voted off of islands. Their hearts are stomped on, as they become rejected suitors. Tears well in their eyes, and they often make statements they wish they could retract. All the while cameras capture every sensationalized second for the consumption of the demographically gifted population of ages 18 to 49. Bob Thompson, director of media studies at Syracuse University, during an interview on In the Money, on Cable News Network, (CNN), discussed the voyeuristic aspect, the window into another persons

Lessons 11 world. We are curious people by nature and want to know what other people do in their private lives (Cafferty, 2003). The plots of reality television shows are charged as being secondary to the spectacle or nonexistent. They insult our intellect. Reality shows are the modern day equivalent to the bread and circuses of ancient Roman plebs, or the public stocks of colonial dissidents. Reality television is the new spectacle that the masses gather around so that they may witness the plights of others, and perhaps in doing so, they feel better about their own lives. One critic suggested that this type of entertainment was inevitable and asks if it is just another way to keep those of the MTV generation aptly entertained (Television Going Down the Drain, 2002). Another criticism leveled at reality television is that it is not even real. Producers often shoot scenes over and over and lead viewers to believe that they captured a spontaneous moment in time. Cast members are portrayed as though they are speaking to the camera in a private, confessional style, when in actuality they are often sitting in front of an interviewer, not shown to the audience, who asks questions designed to elicit desired responses. Former cast members have complained that the production staff instigated arguments or sexual interest among cast members and that alcohol was in plentiful supply in order to fuel such confrontations (Gorlalski, 2004). Reality television is often cited by cultural analysts in an attempt to explain the zeitgeist of these modern times. In the wake of September 11th there was actually a period of time when critics and pop-culture pundits thought that Americans would demand an overhaul of the entertainment industry. It was imagined that family-friendly

Lessons 12 fare such as Touched By an Angel would be insisted upon by a shell-shocked society searching for spiritual comfort and enlightenment in a new era of uncertainty. Instead, the exact opposite seemingly occurred. Talk shows became even more laden with obscenities, commercials for pornographic products such as the Girls Gone Wild video collection could be seen during the daytime, and the reality television genre exploded in popularity. With the recent movement by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to relax the rules of media ownership, critics of controversial television fare like reality television worry. They feel that as the airwaves are monopolized by media conglomerates, less diversity and quality will be seen in the entertainment available to the public, as media giants like Viacom and NewsCorp fight for ratings. Recently reality television has been pushing the drama and comedy out of primetime. American adults watch more television during the hours of prime time (the evening hours between 8:00 and 11:00 PM) than at any other time of day, for an average of eight hours of prime time viewing per week (Smith, Nathanson, & Wilson, 2002). Other research reveals that this time-slot also attracts a large number of child viewers. Research by Stipp (1993) indicated that prime-time shows received higher ratings among 2 to 11 year olds than did Saturday morning cartoons or after-school programs. According to Sex, Kids, and the Family Hour, a 1996 three part study commissioned by the Kaiser Family Foundation, on any given night, nearly six million children between the ages of 2-11 tune in to ABC, CBS, NBC or Fox during "family hour," the first hour of prime-time television, from 8 - 9 p.m (New Study Finds, 1996, para. 2). The term

Lessons 13 family hour now seems inappropriate as this hour is now dominated with reality television shows, which have been charged as being inundated with sexual situations. So who watches reality television? Media studies have recently begun to

put forward more interactive models of why we use the media that we do, that expand on the standard needs-and-gratification models and recognize that viewers are at least somewhat motivated to make their media selections, because of their own characteristics (MacBeth, 1996.) Waite, Bendezu, and Booker (2004) looked at which viewer characteristics predicted a preference for either reality or non-reality television. It was found that heavier reality viewers were less imaginative, more traditional, less open to new experience, and more likely female. Non-reality viewers had higher standards, were more conscientious, preferred organization and planning, and were more likely male. Why It is Important to Study Reality Television Famed media psychologist George Gerbner has referred to television as a modern day equivalent to religion. "Television satisfies many previously felt religious needs for participating in a common ritual and for sharing beliefs about the meaning of life and the modes of right conduct. It is, therefore, not an exaggeration to suggest that the licensing of television represents the modern functional equivalent of government establishment of religion" (Stossel, 1997, para. 20). Television today, like religion in the past, has the power to socialize us with its messages about reality, right and wrong, whats in, whats outcreating a common culture. Gerbner and his colleagues state that the persistent themes of entertainment television subtly shape beliefs among its viewers (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli,

Lessons 14 1994). Even when people recognize that the material they are viewing is fictional, its images and messages can gradually cultivate expectations and beliefs about the real world. This happens as information from the television world is integrated into ones real-world ideas. Gerbner and his colleagues bolster their claim of a cultivation effect with data that show that heavier television viewers have ideas about the real-world that are more congruent with those of the television-world than do light viewers. An immense body of research has documented how powerfully television can serve as a socializing agent for children and adults (Brown & Campbell, 1986). Television influences our ideas on the norms of society and the world around us. Other research has suggested that the narrowness of some television portrayals (such as those deemed racist or sexist) can result in the viewer adapting a skewed view of reality (Brown & Campbell, 1986). Banduras (1986) social learning theory, also known as social cognitive theory, is often used to explain how one learns behavior from television. According to this perspective, such behavior is adapted indirectly, through the observation of models. Rather than elicit specific responses from viewers, models provide us with information. Models, or the characters we see on television, can show us one way to behave in a given scenario, and then, if we encounter a similar scenario in real life, we may choose to imitate them. Thus, we can learn from models, even if we never perform the behavior they have shown us (Miller, 1993). Evidence has even suggested that we may learn more by observing a model work through a problem than by being immersed in the problem

Lessons 15 ourselves. The privilege of being the observer allows us to get a better idea of the overall problem (Miller, 1993). The most popular example of this phenomenon was an influential experiment by Bandura, Ross, and Ross (1961). Preschool children viewed an adult model punching and hitting an inflated Bobo doll with a hammer. A comparison group viewed a model playing calmly with Tinkertoys while a control group did not view a model. Later the children were taken to a room filled with all kinds of toys. The children who had viewed the aggressive model hitting the Bobo doll played more aggressively than children who did not (Miller, 1983). According to Bandura there are four main domains in social learning. They are attentional processes, retention processes, production processes, and motivational processes. Characteristics of both the model and the observer influence attentional processes. A model that is either attractive or powerful will command more attention than one who is not. The behavior of the model also matters. Models engaging in aggressive behaviors are very attention grabbing. Studies show that children are very attentive to models whose behavior may lead to rewards or punishment. Attention to a models behavior is more likely if a model stands out in some way (is salient), is regarded favorably (affective valence), if the models behavior is showcased frequently (prevalence), if the behavior of the model is not particularly complex, and if the models behavior has been shown to be effective (functional value) (Miller, 1993). Several studies have suggested that real people (as opposed to fictional characters) make more

Lessons 16 salient models and therefore can make greater contributions to the viewers observational learning from television (Smith, Nathanson, & Wilson, 2002). An optimal level of arousal and a mature perceptual capacity also promote the paying of attention to notable aspects of the models behavior. Childrens preferences (interests), their cognitive capacity to understand the event, and their perceptual sets (what they anticipate seeing) influence what they will select to pay attention to and process (Miller, 1993). For observational learning to take place, the behavior of the model must not only be observed but must also be retained by the observer. During the retention process, the behavior must be translated into symbols (images or verbal codes), incorporated into the childs cognitive structure and rehearsed. The rehearsal can either be a cognitive rehearsal, when one visualizes carrying out the behavior, or an enacted rehearsal, when one either actually performs the behavior or verbally reviews it. The production process takes place when children mentally select and organize responses to serve as a representational model with which to compare the performed behavior (Miller, 1993, p. 204). The feedback children receive from others allows them to modify the learned behavior. The motivational process refers to a childs desire to engage in behaviors that they see resulting in positive outcomes. Social learning theorists are interested not only in how children come to imitate certain behaviors but why they do so. So how does reality television fit into this paradigm? Does the reality of reality television make these messages and images any more influential? Does reality television

Lessons 17 wield an even greater power of destruction when it comes to the basest of its alleged themes, like sexism and degradation? Research suggests that the realism of the portrayal, may be perceived as more salient or relevant to the observer, and has a powerful effect on aggressive behavior, especially among angered participants (Geen, 1975; Thomas & Tell, 1974). A content analysis of violence on television done by Smith, Nathanson, and Wilson (2002) found that reality television is the most problematic television genre because the perpetrators and victims are real people. The real people aspect of reality television seems to attract viewers because they feel like real people are more relevant than fictional characters. Considering the immense popularity of the genre, the fact that it can be highly influential, and that it is particularly attractive to the youth population, there is a limited supply of scientific research on reality television. A literature review on reality television yields plenty of complaint by the popular press about three alleged themes: humiliation, sex, and gender role imbalances, as well as the concern of media psychologists that violence on reality television may have a more problematic effect on the viewer, as compared to scripted television programs. Humiliation Schadenfreude is a German word that refers to the pleasure one derives from the suffering of others. In English we do not have as concise a word, but if we wanted a visceral example of how it feels to experience this phenomenon, critics might suggest we view a reality television program.

Lessons 18 In dating shows like The Bachelor, a select few chosen from a group of women receive roses from the bachelor, the man who is to choose one among them for a fianc. A rose signifies that he is interested in continuing to date them, while the other women, tacitly deemed less attractive, dont get a rose but instead get to have their tears and anguish caught on film. On Survivor a member is voted out of the tribe at the end of each show, often because they are the least popular with the group. The host extinguishes the contestants torch and says, the tribe has spoken before directing the dejected participant to take a walk of shame away from the group. As director Albert Brooks yells amidst flames at the end of his movie Real Life, The human pathos! Tragedy! And its Real! Real! (Muller, 2002, para. 21). The media critics have even coined a new term humilitainment to describe the appeal of reality television themes. Many viewers and critics alike ask questions such as, Who in their right mind would go on these shows? Do these people understand that they will be humiliated for the entire nation to see? Do they not know that their shame will be immortalized? But there is no shortage of aspiring reality television stars. Many of these people believe that these shows will catapult them to mainstream, A-list celebrity status, but the truth is that many of these stars can hold on to their fleeting fame only for the duration that their particular season of the television show is on the air, or more often, for less time. Perhaps the humiliation theyve endured in the national spotlight causes them to be stigmatized in the eyes of the public. Irene, McGee, who was the recipient of a litany of insults and even a slap from a fellow cast mate during her season of The Real World: Seattle, said that being on the show psychologically traumatized her (Gorlalski, 2004).

Lessons 19 While there are no known empirical studies that have examined the effects of viewing humiliation or degradation on television, there has been no shortage of speculation by media critics on its effect on both the individual and society at large. Bernard Crick, the biographer of the novelist George Orwell, decried a fulfilled prophecy. People are simply depoliticized by cultural debasement, dumbed-down, kept from even thinking of demanding fair shares (Briscoe, n.d., para. 6). He wrote this statement to describe what happened to the characters in Orwells political satire 1984, at the hands of Big Brother. The reality television program of the same name (Big Brother), he suggested, offered the same result. The historic British pastime of bear-baiting involved confronting a bear with a pack of dogs to fight. The bear was usually killed by the dogs. The historian Macaulay said that the Puritans opposed bear-baiting not because it gave pain to the bears but because it gave pleasure to the spectator. The Puritans were right. Some pleasures are contemptible because they are coarsening. They are not merely private vices. They have public consequences in driving the cultures downward spiral (Will, 2001, para. 8). Violence and Aggression The influence of televised violence and aggression on the viewer has been hotly contested since the advent of television. However, nearly every professional organization that researched the issue concluded that viewing violence on television could lead to the aggressive behavior of viewers (Smith, Nathanson, & Wilson, 2002). These organizations include the American Medical Association (1996), The American

Lessons 20 Psychological Association (1993), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1991), the National Institute of Mental Health (1982), and the U.S. Surgeon General (1972). Basically, social learning theory states that violent television can contribute to childrens aggression levels by helping them to form schemas about a dangerous world, by aiding them in creating cognitive scripts for solving social problems that focus on violence, and by helping them to create normative beliefs that violence is acceptable (Huesmann, Moise-Titus, Podolski, & Eron, 2003). Children are natural born imitators. In this way, they model the behavior of those on television. As they grow, children are able to adopt more complex scripts and can engage in more elaborate means of modeling observed behaviors. Additionally, the more extensively children observe violence, the more biased their world view is. They see the world as a more hostile environment than it really is and therefore, more violent ways of dealing with problems seem warranted from this skewed perspective. Empirical research shows that people prone to aggression have easy access to aggressive scripts and schemata, which are activated by the appraisal process (your assessment of a situation) and different input variables (such as personological variables like aggressive personality, and situational variables like videogames and aggressive peers). Accessing these scripts guides and coordinates ones reaction (Anderson & Dill, 2000). In a longitudinal study, which investigated the impact of television violence on aggressive behavior in young adults, Huesmann, Moise-Titus, Podolski, and Eron (2003), during the first portion of the study in 1977, interviewed children on their

Lessons 21 perceived sense of the realism of a variety of violent programs, including cartoons. The children were asked, "How true do you think this program is in telling what life is really like?" Fifteen years later, the participants, who were now young adults, were rated on their levels of aggression. As hypothesized by the researchers, those participants, who as children perceived the violent shows to be more realistic, exhibited greater levels of aggression as adults. In this respect, the perceived realism of reality television may make this genre the most influential on our behaviors. According to one analysis, less than half of all reality television programs shown during prime time contain violence (Smith, Nathanson & Wilson, 2002). According to a 2004 content analysis of reality television sponsored by the Parents Television Council violence on reality television programs took place at a rate of .26 occurrences per hour, down from 1 per hour in 20012002 (Rankin, 2004). There is a very limited supply of empirical studies which examine the effect of reality television violence on the viewer versus traditional scripted programs. These studies suggest that real people (as opposed to fictional characters) make violent acts more attention-getting, more relevant, and therefore present a potentially greater risk of contributing to the observational learning of aggression from television (Smith, Nathanson, & Wilson, 2002). The reality television programs criticized most frequently for their portrayal of violence is the crime/law enforcement subgenre (e.g. Cops, Real Stories of the Highway Patrol, etc.) Perhaps, the most violent show involving real people is The Jerry Springer Show, which is often referred to as a talk show instead, but refers to itself as reality television in its promotional spots. On this program real people can

Lessons 22 be seen striking each other and pulling each others hair, while the studio audience cheers. Sex While there is no indication that watching sexual content on television directly correlates with viewers making irresponsible choices with their sexual activity, the research does suggest that television viewing may help form viewers attitudes about sexual relationships and activity. These attitudes or beliefs in turn, are some of the strongest predictors of the viewers sexual behavior. This hypothesis connects attitudes about sexuality shaped by the American media with disturbing sexual statistics, such as a higher rate of teen pregnancy in the United States than in any other industrialized nation (Sexuality in the Mass Media, 2004). According to the University of California at Santa Barbaras report, Sexuality in the Mass Media: How to View the Media Critically, about 66% of prime time shows contain sexual content and, with each new year, television programs have more sexual content than the year before. The television programs most popular with teenagers have the most sexual content. The majority of the sexual acts occur between characters that are unmarried. One study found that heterosexual unmarried characters had sexual intercourse four to eight times as often as characters who were married (Sexuality in the Mass Media, 2004). Research seems to suggest that television rarely addresses the risks involved with sexuality activity. The contraction of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the use of contraceptives is rarely part of a television script. STDs were only discussed an average of once for every ten hours of programming according to one

Lessons 23 study. According to the Committee on Public Education about 14,000 sexual references are viewed by the average American adolescent per year, but only 165 of these will deal with self-control, abstinence, birth control, or the risk of pregnancy or STDs (Committee on Public Education, 2001). There have been several studies that have shown the link between viewing sexual content and the shaping of sexual attitudes. Some studies have connected increased viewing of sexual content on television with dissatisfaction with virginity among adolescents, (Brown & Newcomer, 1991; Peterson, et al, 1991; Kunkel, et al, 1999). One study found that students who thought television portrayed sex in a realistic manner were more likely to be disappointed with their own first experience with sexual intercourse (Brown & Newcomer, 1991:80). Another study found that adolescents who viewed a drama which centered around highly sexual themes rated descriptions of a casual sex encounter more favorably than those who had not viewed the same sexual content (Bryant & Rockwell, 1994). Yet another study of black females between the ages of 14 to 18 found that those who viewed X-rated films had less-favorable attitudes toward contraceptive use than those who did not (Wingood, et al., 2001). Another study found that teenagers who viewed more sexual content on television were more likely to have engaged in sexual activities. The researchers concluded that watching sex on television can predict and can even hasten an adolescents involvement in sexual activity (Colins, et al., 2004). Reality television shows, especially those in the dating subgenre (e.g. Temptation Island, The Fifth Wheel) are constantly described as brimming with sex. Temptation

Lessons 24 Island caused an outcry from religious and moral leaders as its promos suggested salacious depictions of sexuality, and it was found that the stars of the show were required to be tested for sexually transmitted diseases. In a content analysis published by the Parents Television Council (PTC), Rankin (2004) analyzed the first four episodes of twenty nine popular reality television programs for foul language, sex, and violence. Analyses for sexual content found the following: While sexual innuendo (verbal allusions to sex) occurred more often than other forms of sexual content in this analysis, nudity was the second most common form of sexual content on reality television programs. The per-hour rate of sexual content on reality television programs was 4.3, which is 169% higher than the per-hour rate of a similar 2002 study. While there have been no studies that specifically look at the effects of sexual content on reality television versus traditional scripted programs, one has to wonder whether the reality component of reality television causes the modeling of sexual behavior to be even more salient in shaping sexual attitudes. Gender Role Imbalances It is believed that gender role stereotypes as portrayed on television can lead to the development of our culturally shared gender role standards (Waite, 1988). According to the research of Sandra Bem, androgynous individuals are more adaptable than those who adhere strictly to traditional masculine or feminine prescriptions for behavior. This is because androgynous individuals can utilize an entire spectrum of traditional male and female traits, such as compassion, sensitivity, and cooperativeness on the female dimension, and leadership, initiative, and competitiveness on the male dimension. It

Lessons 25 appears, therefore, that an androgynous gender role orientation is most favorable for psychological well-being for men and women (Pyke, 1980). Many studies indicate that androgynous people have higher self-esteem, are freer and more flexible with their behavior, make better decisions when in group situations involving both genders, are more socially competent, and have higher motivation to achieve, as compared to people who adhere to traditional gender roles (Crooks & Baur, (2002). Content analyses of network television have shown that stereotypic gender role differences can be observed during average programming. Generally studies have demonstrated that men are shown more often than women and are depicted as older, better problem solvers, more powerful and as higher achievers (Signorielli, 1985). Women are portrayed as victims more often than men, and are depicted as being more dependent and emotional, less competent, and as an addition to a mans life (Huston, et al, 1992). Men are also viewed as more dominant than women (Henderson & Greenburg, 1980). Women are viewed as being more submissive or subservient. A common criticism of television is the objectification of women, by focusing on their bodies and appearance. Many feminists and psychologists alike believe that this sends a message that physical attractiveness is of the utmost importance in subscribing to the female gender role. Some fear that the focus on the superficiality of appearance discourages girls and women from seeing the importance of cultivating their whole person, and that their intellectual and emotional potentials may not be fulfilled (Pipher, 1999).

Lessons 26 While there are no known empirical studies that specifically look at the effects of gender role imbalances on reality television versus traditional scripted programs, one has to wonder whether the reality component of reality television contributes even more to the shaping of our culturally shared gender role standards and stereotyping. Reality television shows, especially those in the dating subgenre (e.g. The Bachelor, Joe Millionaire) have been accused by many feminists and critics alike as being sexist and enforcing antiquated gender roles. On both The Bachelor and Joe Millionaire the central figure is a male who gets to choose which female he desires above the rest. This androcentric scenario has often been equated to that of a man choosing a partner for the evening among his harem. These shows are also charged as featuring women as catty, competitive, jealous stereotypes, who are obsessed with their appearance. The National Organization for Women (NOW) in its 2002 Feminist Prime Time Report, gave The Bachelor an F on its report card style rating system. When the American Broadcasting Network (ABC) announced that it was creating a copy-cat show where the woman was the center of power, and got to choose her mate among a group of men, critics cried that this format wouldnt work because of the sexuality double standard (a woman could not be endeared to the public if she dated many men). On an episode of My Big Fat Obnoxious Boss, two women were praised for wearing skimpy clothing in order to sell merchandise during a sales challenge. The men on their team said that they had to pimp their female teammates in order to win.

Lessons 27 Hypotheses The purpose of this study was to begin to address some of the gaps due to the lack of scientific research on reality television. Specifically, I sought to examine the charges made by the popular press about reality television programs. This study focused on those categories of interest most commonly addressed by the critics in relation to reality television programs: humiliation, violence and aggression, sex, and gender role imbalances. I looked at these variables across race, age, and gender data, so that I could see if different demographic groups were represented adequately, so I could see how different groups of people are portrayed in the reality television world, and so I could get a better understanding of what messages viewers may receive from such portrayals. I also content-analyzed scripted television shows, both comedies and dramas, and compared the results of these analyses to those of the reality television programs. Primary Hypotheses At the conclusion of this literature review and after my own informal analyses I hypothesized that the critics of reality television are correctthat these shows do feature more humiliation, sex, and gender role imbalances. However, since it was found that less than half of all reality television programs contain violence (Smith, Nathanson, & Wilson, 2002), I did not believe that they display any more violence than other types of television shows. Specifically, I hypothesized that reality shows contain more humiliation, sex, and gender role imbalances, than scripted comedies or dramas, but that scripted dramas have more violence than reality television programs and scripted comedies.

Lessons 28 Secondary Hypotheses My secondary hypotheses had to do with how different demographic groups are represented on reality television. According to Children Nows report, Fall Colors 200304: Primetime Diversity (Glaubke & Heintz-Knowles, 2004) 73% of the total characters featured during primetime were white, while other racial groups were very underrepresented or non-existent. While 65% of primetime characters were men only 35% were women. Based on this information I hypothesized that the majority of the characters on all three types of shows would be white. I also hypothesized that since many reality television programs thrive on sexual drama, that there would be about an equal amount of men and women in the casts. For both scripted comedies and dramas, I hypothesized that there would be a heavier concentration of men. Finally, from my own informal analyses, I hypothesized that the reality television cast of characters is primarily younger (34 and younger). This is because many of the reality television programs focus on people who appear to be in their twenties or early thirties, especially in the dating subgenre. I believed that scripted comedies and dramas would have a larger representation of older (35 and older) adults than reality television programs as many comedies center around marriage and parenting, and many dramas center around characters in advanced stages of career (e.g. detectives, doctors, lawyers, etc).

Lessons 29 Method Sample A sample of fifteen prime-time television shows was drawn from three categories: reality television, scripted comedy, and scripted drama. The five programs with the highest ratings according to Nielsen data were selected from each genre. The selection of shows was based on Nielson ratings data from April 2004. The five reality television programs with the highest ratings analyzed were: The Apprentice, The Bachelor, Fear Factor, Survivor and The Swan. The five scripted dramas with the highest ratings analyzed were: CSI, CSI Miami, E.R., Law & Order, and Without a Trace. The five scripted comedies with the highest ratings analyzed were: Everybody Loves Raymond, Frasier, Friends, Two and a Half Men, and Will and Grace. Raters Two female volunteers from Connecticut undergraduate colleges participated as raters. Raters received training on the behaviors of characters that would qualify as falling into each of the four categories of interest: humiliation, violence/aggression, sex, and gender role imbalances. Raters were then thoroughly trained in use of the coding sheet. Coded Behaviors The raters recorded the occurrence of ten subcategories of behavior by means of a time sampling method. The raters were told that they could code different behaviors within the same one minute interval. The creation of these behavioral categories, specifically the use of detailed descriptors, was guided by and adapted from the research

Lessons 30 of Sommers-Flanagan, Sommers-Flannagan, and Davis (1993), Brown & Campbell (1986}, and by Baxter, De Riemer, Landini, Leslie, and Singletary (1985). The behavioral categories to be coded were as follows: Humiliation. Words, actions, or situations that could reasonably cause one to lose self-respect, the respect of others present, or the respect of the viewer: verbal insults, getting voted out of a group, being sent home, manipulation of footage by editors to emphasize embarrassing moments or bad personal traits, getting fired, etc. Violence and Aggression. The following acts of aggression were recorded with a note as to whether the characters involved were perpetrators or recipients: bodily assaults, with and without an object; bombing; detaining; physically threatening; use of weapons; physical aggression toward an object; physical aggression toward oneself; chase; murder. Implicit Sexuality. Instances in which themes of sexual attraction are predominant but where no sexual activity (e.g. physical contact with others) takes place. Scenes that seem to appeal to the erotic or to elicit sexual arousal, such as pelvic thrusts, long lip licking, etc. Also sexual innuendo and verbal references to sexuality. Explicit Sexuality. Sexual acts that are observed (e.g. kissing, groping, intercourse). Objectification. : Focusing (as with camera) on persons body parts instead of whole person. Examples include focusing on cleavage, bare stomach, lips, genital areas, buttocks, thighs, etc. Simply filming from the waist up or getting a close-up of the face is not objectification.

Lessons 31 Dominance. A person is clearly in the position of dominating another (not by physical force). The dominant person is part of a scenario in which they hold control. Subservience. A person is clearly in the position of being dominated by another, (not by physical force). The subservient person is part of a scenario in which another person holds control. Aggression with Sexuality. Situations in which one person is being sexually aggressive with another. The word aggressive in this context suggests the energetic pursuit of a sexual goal. It should not be confused with violent aggression. This may include sexual propositioning, or even sexual harassment. Physical contact is not required but there must be a sexual motive in connection with the aggression. Whether the character was a perpetrator or recipient was noted. The following points were made to raters to clarify how to code certain behaviors: Verbal insults would be coded as humiliation, unless they included physical threatening, which would be coded as violence and aggression. Rape would fall under the violence and aggression category, as the aggression with sexuality category does not include violence. The main difference between the aggression with sexuality category and the implicit and explicit sex categories is that this behavior emphasizes the observation that one person is the sexual aggressor and one is the recipient. If both parties seem equally aggressive then this behavior has not been observed.

Lessons 32 Superordinate Variables For analysis purposes, at the conclusion of the coding, the ten behavioral subcategories coded were then combined into four superordinate categories of interest. These superordinate categories were: humiliation, violence and aggression, sex, and gender role imbalances. The subcategories of implicit and explicit sex were combined into the superordinate sex category while the subcategories of objectification, dominance, subservience, and aggression with sexuality were combined into the superordinate gender role imbalances category. While the aggression with sexuality behavior includes a sexual pursuit, the reason why it was combined into the gender role imbalances superordinate category and not the sex superordinate category is because one person is clearly the aggressor and one person the recipient. There is an imbalance in the interest of each party. If both parties are equally sexually aggressive then this behavior has not been observed. It is the gender role imbalances superordinate category that concerns an imbalance of power among the genders, sexual or otherwise. This is also why dominance, subservience and objectification were included in the gender role imbalances superordinate category. Coding Sheet The coding sheet contained one behavior category on each row. Each row was divided into boxes representing one-minute intervals. Each time one of the behaviors of interest occurred, the rater went to the coding sheet representing the demographic group or groups involved and placed a tally mark in that behaviors row of the table, in the box

Lessons 33 representing the present one-minute interval. If a given behavior did not occur within the one-minute interval, with respect to the demographic group represented on the coding sheet, the rater put a 0 in the box. Each coding sheet listed the program title (i.e. Survivor), program type (reality, scripted comedy, or scripted drama), and duration of the show (not counting commercials). The coding sheets also contained demographic data: age group, gender and ethnicity. For the purpose of analyzing how different demographic groups are portrayed on television, all characters were grouped into different demographic categories based on these three variables (e.g. elderly black males, middle-aged Asian females, etc). Each program was viewed by the author in advance to determine the number of demographic groups present. One coding sheet for each demographic group featured on the given program was distributed to each rater. For example, all young white female characters on Survivor were rated using one coding sheet. The coding sheet also listed the number

of members/characters of that particular demographic group featured during the given program. The raters also recorded the total amount of screen time that members of that demographic group were present during each show. On each coding sheet was a row titled Screen Time. The row was divided into boxes, each representing a one-minute interval. If members of the given demographic group were present during the one-minute

Lessons 34 interval being rated at the moment, the rater placed a tally mark in the box for each member of the group present. If no members of the given demographic group was present, the rater placed a 0 in the box. (For a sample of the coding sheet see Appendix 2). Procedure After thorough training on use of the coding sheet and on recognizing the behaviors to be coded, the two raters participated in a practice coding session. As part of the training the raters rated ten minutes of a sample of each type of show (reality, comedy, and drama). After the practice session, inter-rater agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements. An agreement was defined as each of the raters having coded the same one-minute interval with the same behaviors. If the inter-rater agreement percentage was under eighty the raters participated in additional practice coding sessions until inter-rater agreement of eighty percent or higher was established. Raters then rated the fifteen shows (no more than two to three shows were rated per day so that raters were able to remain alert). One show was rated at a time. The programs were paused at one-minute intervals that were timed using a digital stopwatch. Raters coded the coding sheets during the pause.

Lessons 35 Results Unit of Analysis For per character behavior analyses, the unit of analysis was the total frequency of a category of behaviors, for a given demographic group, per show, divided by the number of minutes in the show (without commercials). This result was then divided by the number of characters in the demographic group and then multiplied by sixty, in order to present the data in a per hour format. For per show behavior analyses, the unit of analysis was the total frequency of a category of behaviors, for a given demographic group, per show, divided by the number of minutes in the show (without commercials). This result was then multiplied by sixty, in order to present the data in a per hour format. Preliminary Analyses All shows analyzed in this study were between 20 to 48 minutes in length and the mean length was 39.62 minutes long with a standard deviation of 10.07 minutes. To estimate inter-rater agreement Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the level of agreement between the two raters, with respect to each of the ten behavioral subcategories that were coded. Inter-rater agreement correlations are reported in Table 1. Intercorrelations among all superordinate behavioral variables are presented in Table 2. Preliminary analyses indicated that there was an under-representation of all ethnic groups other than whites. Thus, analyses by ethnicity could not be conducted. Initial analyses also indicated that humiliation for single white women in one reality show, The

Lessons 36 Swan, was so high that it was an outlier that led to distorted statistical results. I excluded The Swan from the data before conducting the MANOVAs and ANOVAs that I report later. Per Character Analyses In order to examine the relations of type of show, gender, and age group with the dependent variables, three way (show type x gender x age group) incomplete factorial multivariate analyses of variance were conducted on the four per character superordinate variables (humiliation, violence/aggression, sex, and gender role imbalances). The threeway interaction was not estimated due to insufficient n in some cells. Multivariate F ratios were generated from Pillais Trace criteria. Significant (p < .05) multivariate effects were followed by univariate analyses of variance to locate the source of the effects. Multivariate and univariate analysis of variance results are presented in Table 3. Multivariate main effect of type of show was significant. All other main effects and two-way interactions were not significant. Univariate ANOVA tests for main effect of type of show were significant for the superordinate variables humiliation, violence/ aggression and sex. Means and standard deviations for the main effects of show type are presented in Table 4. Least Significant Difference (LSD) multiple comparison tests indicated that the amount of humiliation per character present in reality shows and comedies was significantly greater than that of dramas. LSD tests also indicated that the amount of violence/ aggression per character present in dramas was significantly greater that that of reality shows and comedies. Additionally, LSD tests indicated that the amount of sex per character present in comedies is significantly greater than that of

Lessons 37 reality television programs or dramas. Means and standard deviations for non-significant per character effects are presented in Tables 5-9. Per Show Analyses In order to examine the relations of type of show, gender, and age group with the dependent variables, three way (show type x gender x age group) incomplete factorial multivariate analyses of variance were conducted on the four per show superordinate variables (humiliation, violence, implicit and explicit sex, and gender role imbalances). The three-way interaction was not estimated due to insufficient n in some cells. Multivariate F ratios were generated from Pillais Trace criteria. Significant (p < .05) multivariate effects were followed by univariate analyses of variance to locate the source of the effects. Multivariate and univariate analysis of variance results are presented in Table 10. Multivariate main effect of type of show was significant. All other main effects and two-way interactions were not significant. Univariate ANOVA tests for main effect of type of show were significant for the superordinate sex variable. Means and standard deviations for the main effect of type of show are presented in Table 11. LSD multiple comparison tests indicated that the amount of sex per show present in comedies, is significantly greater than that of reality shows or dramas. Although univariate Fs for humiliation and violence by show type did not differ significantly for per show analyses at the traditional alpha level (p < .05), they did approach significance (p < .06). Use of this less stringent alpha level would have yielded a pattern of results similar to those of

Lessons 38 per character effect for humiliation and violence. Means and standard deviations for non-significant per show effects are presented in Tables 12-16. Demographic Analyses Demographic comparisons among types of shows (e.g. reality, scripted comedy, and scripted drama) were conducted. In order to examine my hypothesis about whether the number of persons in each age group (younger vs. older) varied by show type, I conducted a two-way between subjects analysis of variance (show type x age group) using the number of people in each age group that were present in each show type as the dependent variable. Results indicated that there were no significant main effects or interactions although a trend towards more younger cast members on reality television is noted. See Table 17 for ANOVA results. See Table 18 for interaction means. In order to examine my hypothesis about whether the number of persons of each gender (men vs. women) varied by show type, I conducted a two-way between subjects analysis of variance (show type x age group) using the number of people of each gender that were present in each show type as the dependent variable. Results indicated that there were no significant main effects or interactions. See Table 19 for ANOVA results. See Table 20 for interaction means. Discussion This content analysis allowed me to examine empirically the charges that media critics have leveled towards reality television. While I hypothesized that reality television programs would have more humiliation than scripted comedies or scripted dramas, the results indicated that both reality television programs and comedies have

Lessons 39 significantly more humiliation per character than do scripted dramas. And although per show analyses for humiliation were not significant, results approached significance. It is worth repeating that the amount of humiliation for young white women on the reality television program The Swan was so high that the data was excluded from the analyses. During several one-minute intervals of this show, each rater had coded over one hundred incidences of humiliation, as cosmetic surgeons pointed out every perceived flaw of the two participants who had signed up for a complete cosmetic surgery makeover. Based on both the per character results for humiliation and my informal analyses I believe that reality television shows feature humiliation prominently, as a central aspect of the plot. While this empirical analysis demonstrates that both reality television programs and scripted comedies contain significantly more humiliation than do scripted dramas, one major difference between reality television programs and scripted comedies is that scripted comedies contain humiliation which is usually in the form of jokes which are followed by laugh tracks. For example, On Everybody Loves Raymond, fictional characters such as Raymonds mother Marie and wife Deborah trade quips as Marie insinuates that Deborah is an inferior homemaker and cook. Laughter can be heard after each one-liner and so this type of fictional humiliation appears to be all in good fun. Is there a difference between observing this type of pretend, fun humiliation among fictional people and observing a real person being degraded? As I hypothesized, the amount of violence and aggression per character present in dramas was significantly greater than that of reality television programs and comedies.

Lessons 40 And although per show analyses for violence and aggression were not significant, results approached significance. This should come as no surprise, as four of the five dramas analyzed have themes involving murder and crime (e.g. CSI, Law & Order, Without a Trace, etc.) It should be noted that none of the five reality television programs analyzed were of the law enforcement variety (e.g. Cops, Worlds Wildest Police Chases, etc.). This subgenre usually showcases a fair amount of violence and aggression and as stated earlier, the reality television variety of television shows which contain violence has been found to be the most problematic (Smith, Nathanson, & Wilson, 2002). Contrary to my hypothesis, which was that reality television programs would contain more sex than traditional scripted comedies or scripted dramas, the analyses revealed that the amount of sex per character and per show present in scripted comedies is significantly greater than that of reality television programs or scripted dramas. It should be noted that four of the five reality television programs analyzed are not of the dating subgenre, which is most often cited by critics as being laden with sex (e.g. Temptation Island, Elimidate, Paradise Hotel, etc.). Based on my informal analyses I believe that if the majority of reality television programs coded were of the dating subgenre then there would have been a significantly greater amount of sex found in reality television programs than in scripted comedies or scripted dramas. It also should be noted that four of the five scripted comedy episodes

analyzed dealt with sexual themes. According to the University of California at Santa Barbaras report, Sexuality in the Mass Media: How to View the Media Critically, the

Lessons 41 sexual content of sitcom scenes saw an increase of 56% in 1999 and 84% in 2000 (Sexuality in the Mass Media, 2004). Also contrary to my hypothesis was the fact that reality television programs did not contain significantly more gender role imbalances than scripted comedies or dramas. Based on my informal analyses I feel that if the majority of reality television programs coded were of the dating subgenre, then there would have been a significantly greater amount of gender role imbalances found in reality television programs than in scripted comedies or scripted dramas. My hypothesis about whether the number of persons in each age group (i.e. younger vs. older) varied by show type, was correct, there are more younger (34 and younger) people featured in reality television programs and more older (35 and older) people featured in comedies and dramas. I had hypothesized that the number of persons in each age group (younger vs. older) and in each gender (men vs. women) would vary by show type. I had thought that there would be more younger people in reality television programs than in dramas and comedies, but more older people in comedies and dramas than in reality television programs. I had thought there would be an equal number of men and women in reality television programs because of the sexual situations that cast members are often placed in, but that there would be more men than women in dramas and comedies. Neither of these hypotheses was correct, as there was no significant difference in these groups according to show type. As discussed earlier, according to the attentional process component of social learning theory, viewers pay more attention to models on television that are more

Lessons 42 salient. Are not characters on reality television automatically more salient in that they are supposedly being themselves and not acting? Is not reality television therefore a ticket to a more exclusive window on the world? As discussed earlier viewers also pay more attention to models whose behavior leads to reward or punishment. On Survivor tribe members participate in reward challenges and winners are supplied with steak dinners, wine and exotic yacht excursions, whereas the losers may lose their last rations of rice. On the Apprentice Donald Trump rewards those who do great work on the job by placing them one step closer to a six-figure income and give them an immediate reward such as meeting Rudolph Giuliani or enjoying a fine dinner at an oceanfront estate, whereas those whose job efforts fall short are sent to the boardroom where they are chastised and may even be punished with the words Youre fired! The motivational process component of social learning theory is concerned with how and why viewers imitate behaviors. The irony of reality television is that many reality television shows thrive on behaviors and scenarios that people otherwise would never encounter in reality. How often can a man select a mate out of a group of 16 hopefuls, like on The Bachelor? How often do people get trapped on exotic islands and have to compete in potato sack races to win food, like on Survivor? And would as many teenagers engage in risky stunts like rolling off of the roof of their garage in a garbage can if Jack Ass was never on the air? The models on Jack Ass were not represented as Hollywood stuntmen, but as average guys with an appetite for adventure. Viewers could easily model their behavior. Perhaps the reality of the show made those who tried the stunts feels confident that a real person could execute the stunt and survive the danger,

Lessons 43 despite the numerous warnings and disclaimers at the beginning of the show. And while the situations depicted on reality television are often abnormal, viewers can still observe the normal everyday interactions between real people (i.e. arguments, conversations, etc.) and perhaps are more inclined to model such behaviors as the characters are supposed to be representing the way people act in the real world. As stated earlier Gerbner and his associates believe enduring themes of television entertainment help shape viewers beliefs (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1994). If people try to act out stunts featured on reality television programs like Jackass and Fear Factor because they think, Well, if real people can do it, so can I, or This must be normal behavior since real people are doing it, then does the same type of thought process exist for some when it comes to viewing models exhibiting or being the recipient of humiliation, violence, sex, and adhering to gender stereotypes? Now that we have analyzed the content of reality television, the next step in the empirical study of this entertainment phenomenon would be to further test the relevance of social learning theory when it comes to this question of the impact of the reality of reality television on the viewer. As television in general went ever-wilder after September 11th, contrary to critics predictions, we saw the premises for reality television shows also get wilder. In recent months, some media pundits have suggested that we would witness the very beginning of a shift of the cultural pendulum to the more conservative end of the spectrum. On February 1, 2004, during the Super Bowl XXXVII halftime show, a risqu performance by Janet Jackson and Justin Timberlake, in which Jacksons breast was

Lessons 44 exposed to over 90 million viewers, incited a public outcry for higher standards of decency on television. In addition to the racy halftime spectacle, several of the advertisements shown during the game featured jokes utilizing scatological humor which also offended many viewers. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was flooded with angry phone calls and emails from outraged Americans, many of whom were watching the program with their children, who could not believe that such material was allowed to air on a broadcast television network, during a family show. FCC Chairman Michael K. Powell issued a statement: "I am outraged at what I saw during the halftime show of the Super Bowl. Like millions of Americans, my family and I gathered around the television for a celebration. Instead, that celebration was tainted by a classless, crass and deplorable stunt. Our nation's children, parents and citizens deserve better" (Ahrens & de Moraes, 2004, para. 6). The other FCC commissioners issued comparable statements. The FCC announced that same week that they would be launching an investigation that would probe the entire halftime performance. If the investigation determines that indecency violations occurred, each of Viacom's 200 owned and affiliate stations would be fined up to $27,500 (Ahrens & de Moraes, 2004 para. 3). In the media blitz that followed, many psychologists were called upon to explain the cause of the public furor. Many psychologists espoused that the publics anger to this Super Bowl halftime performance was the result of years and years of their viewing the entertainment industrys degeneration. This pent-up frustration finally exploded in a public relations fiasco for Viacom, the parent company of both Music Television (MTV)

Lessons 45 and Cable Broadcasting System (CBS), the two media outlets held responsible for airing the spectacle. On a February 4, 2004 episode of Scarborough Country that focused on the controversy, Dr. Drew Pinsky explained why parents were justifiably concerned. He stated that viewing such behavior on television can establish a societal norm. In the months that followed the Super Bowl halftime controversy the FCC has taken aim at other entertainers frequently accused by the public of violating decency standards, including shock jocks Howard Stern, and Mancow Muller. On his nationally syndicated radio show, on Friday March 5, 2004, Howard Stern predicted that a Federal Communications Communication crackdown on indecency in entertainment would force his controversial show off the airwaves. On his program he announced, "I'm guessing that sometime next week will be my last show on this station, adding that he anticipated that the FCC would charge him with a large indecency fine. "There's a cultural war going on. The religious right is winning. We're losing." (Howard Stern predicts his broadcasting demise 2004). Clear Channel Communications pulled Stern from radio stations in San Diego, Pittsburgh, Rochester, New York, Louisville, Kentucky, and Fort Lauderdale and Orlando, Florida on February 25. The company announced that the Stern show suspension would last until the show was in compliance with the companys programming guidelines. "This time they have to fire me," Stern said. "I'm through. I'm a dead man walking." (Howard Stern predicts his broadcasting demise 2004). Whether or not we are truly witnessing the gradual shift in the cultural pendulum, is up for debate. It seems whenever a shift begins, as it did with both the post-September

Lessons 46 11th climate and post-Super bowl backlash, it is quickly countered with even more controversial programming. Even though Howard Stern has now announced that he is moving to Sirius satellite radio, as to not be governed by FCC decency rules, we now have Desperate Housewives, a new sex soap drama that has recently garnered many headlines regarding its controversial content and a sexualized promotional commercial that one of its stars filmed with a professional football player to open a presentation of Monday Night Football on ABC. Recently The Jerry Springer Show, which boasts that it was once voted the worst show in the history of television has returned to showcasing physical violence among its guests. This talk show has even begun referring to itself as reality television and invites the viewer to get a ringside seat. So this cultural climate change may or may not have ever existed, or may have existed briefly. But as Howard Stern feared, the Bush administration has been voted back into Washington for another four years, and many feel that the FCC will be more aggressive in its pursuit of decency violations. Perhaps reality television will be the next entertainment medium to come under fire and to be monitored closely by the FCC. For this reason further empirical study into reality television regarding the effects of its contents on viewers from a social learning perspective is necessary. The results of this content analysis reveal that the means for occurrences of humiliation tend to be much higher than those of the other behavioral categories of interest. This seems to indicate that the media critics were correct when they coined the term humilitainment to describe reality television. Perhaps it is not the reality television medium, but its common content that may be problematic. Since reality

Lessons 47 television, by its title alone, gives the delusion that it represents real life, it certainly has the potential to contribute to negative societal norms. Can reality television as a medium, be used for higher causes than humilitainment? Can reality television contribute to positive societal norms? Jeffrey Shaffer from the Christian Science Monitor has an idea on how the reality television medium can be utilized in a very different manner. He proposes a show set in Kabul that follows our troops as they try to rebuild Afghan society (Reality TV: How Low Can We Go?, 2003, para. 3). According to Schaffer, viewers need to be reminded that the public owns the airwaves, not the networks. Networks are licensed to operate in the public interest. They were never intended to be corporate cash machines (Reality TV: How Low Can We Go?, 2003, para. 3). Imagine this concept, using reality television to actually improve reality!

Lessons 48 Table 1 Correlations for Inter-rater Agreement for Each of the Behavioral Subcategories

Variable Humiliation Violence Perpetrator Violence Recipient Sex- Implicit Sex- Explicit GI- Objectification GI- Subservience GI- Dominance GI- Aggression w/ Sex Perpetrator GI- Aggression w/ Sex Recipient

r .999 .986 .999 .992 .998 .952 .998 .939 1.000 1.000

N = 88 Note. Values may be inflated for some variables because of large number of agreements due to the absence of codable behavior. Note 2. GI is an abbreviation for Gender Role Imbalances.

Lessons 49 Table 2 Intercorrelations among all Superordinate Behavior Variables

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ________________________________________________________________________ Per Character 1. Humiliation 2. Violence 3. Sex 4. GenImbal Per Show 5. Humiliation 6. Violence 7. Sex 8. GenImbal .914* -.037 .181 -.019 .077 .183 .077 .118 .087 -.149 .203 -.017 .200 -.118 ---.059 .198 .050 --.034 .153 -.048 --

.917* -.044 .011 .153 .968* -.003

.614* .060

Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex and Gender Role Imbalances. * p = < .01.

Lessons 50 Table 3 Multivariate and Univariate Analysis of Variance for Per Character Superordinate Behaviors_______________________________________________________________ Multivariate Source Show Type ac (ST) Gender (G)d Age Group (AG)d ST x Gc ST x AGc df 8 4 4 8 8 ___________Univariate_F____________________ Humiliation 4.95* 0.05 0.04 0.08 2.06 Violence Sex GenImbal 3.18* 7.75*** 0.48 0.69 0.01 0.21 0.02 0.68 0.06 0.48 0.01 4.76* 0.41 2.21 3.20*

F 2 3.78a*** .176 1.77b 0.13b 0.74a 1.25a .092

..007

.040 .066

G x AGd 4 0.71b .039 0.30 1.00 0.84 1.51 Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex and Gender Role Imbalances. Multivariate F ratios were generated from Pillais statistic. *p < .05.

aMultivariate bMultivariate cUnivariate dUnivariate ***

p <.001.

Error df = 142. Error df = 70.

df = 2, 78. df = 1, 78.

Lessons 51 Table 4 Main Effect of Type of Show Means and (Standard Deviations) for Superordinate Behaviors Per Character___________________________________________________ Main Effect Show type_ Reality Humiliation 4.62a (5.89) Drama 1.35b (1.74) Comedy 6.16a Violence 0.04a (0.14) 0.28b (0.63) 0.03a Sex 0.11a (0.38) 0.32a (0.87) 3.97b GenImbal ____ 0.21 (0.47) 0.24 (0.62) 0.27

(5.86) (0.15) (6.68) (0.86) Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex, and Gender Role Imbalances. Note 2. Means with different subscripts within a column differ significantly (p < .05 or beyond) using LSD multiple comparison tests.

Lessons 52 Table 5 Main Effect of Gender Means and (Standard Deviations) for Superordinate Behaviors Per Character_______________________________________________ Main Effect Gender Men Humiliation 3.52 (5.05) Women 3.63 Violence 0.20 (0.57) 0.09 Sex 1.00 (3.77) 1.27 GenImbal 0.11 (0.31) 0.36 __

(4.89) (0.24) (3.56) (0.83) ____________________________________________________________________ Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex, and Gender Role Imbalances.

Lessons 53 Table 6 Main Effect of Age Group Means and (Standard Deviations) for Superordinate Behaviors Per Character__________________________________________________ Main Effect Age Group Younger Humiliation 3.97 (5.38) Older 3.30 Violence 0.13 (0.39) 0.16 Sex 0.87 (3.05) 1.31 GenImbal 0.35 (0.70) 0.16

(4.64) (0.48) (4.03) (0.58 ____________________________________________________________________ Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex, and Gender Role Imbalances.

Lessons 54 Table 7 Show Type x Age Group Interaction Means and (Standard Deviations) for Superordinate Behaviors Per Character__________________________________________________

Humiliation Reality Younger Older Drama Younger Older Comedy Younger 4.25 (5.89) 1.38 (2.26) 1.34 (1.42) 5.99 (6.34) 2.62 (4.74)

Violence

Sex

GenImbal

0.04 (0.11) 0.06 (0.19)

0.15 (0.48) 0.06 (0.15)

0.35 (0.57) 0.00 (0.00)

0.29 (0.59) 0.28 (0.66)

0.35 (0.53) 0.30 (1.02)

0.49 (0.94) 0.09 (0.25)

0.00 (0.00)

4.52 (7.44)

0.00 (0.00)

Older 6.79 (5.91) 0.05 (0.18) 3.78 (6.67) 0.37 (0.99) ____________________________________________________________________ Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex, and Gender Role Imbalances.

Lessons 55 Table 8 Show Type x Gender Interaction Means and (Standard Deviations) for Superordinate Behaviors Per Character__________________________________________________

Humiliation Reality Younger Older Drama Younger Older Comedy Younger 6.11 (6.25) 1.55 (1.68) 1.16 (1.82) 4.04 (6.19) 5.15 (5.78)

Violence

Sex

GenImbal

0.08 (0.20) 0.01 (0.04)

0.16 (0.52) 0.07 (0.17)

0.19 (0.45) 0.22 (0.50)

0.38 (0.82) 0.19 (0.34)

0.20 (0.38) 0.43 (1.17)

0.10 (0.27) 0.37 (0.82)

0.06 (0.21)

3.29 (7.06)

0.03 (0.10)

Older 6.20 (5.72) 0.00 (0.00) 4.79 (6.50) 0.57 (1.25) ____________________________________________________________________ Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex, and Gender Role Imbalances.

Lessons 56 Table 9 Gender x Age Group Interaction Means and (Standard Deviations) for Superordinate Behaviors Per Character__________________________________________________

Humiliation Men Younger Older Women Younger Older 4.56 (5.60) 2.83 (4.14) 3.23 (5.19) 3.68 (5.06)

Violence

Sex

GenImbal

0.15 (0.48) 0.23 (0.62)

0.25 (0.58) 1.42 (4.66)

0.17 (0.42) 0.08 (0.23)

0.11 (0.30) 0.06 (0.18)

1.36 (4.02) 1.18 (3.19)

0.50 (0.85) 0.25 (0.82)

____________________________________________________________________ Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex, and Gender Role Imbalances.

Lessons 57 Table 10 Multivariate and Univariate Analysis of Variance for Per Show Superordinate Behaviors _______________________________________________________________________ Multivariate Source Show Type ac (ST) Gender (G)d Age Group (AG)d ST x Gc ST x AGc df 8 4 4 8 8 F 3.26a* 1.37b 0.41b 0.31a 0.82a _________Univariate F______________________ 2 Humiliation Violence .155 2.30 2.24 .072 .023 .017 .044 0.88 1.13 0.14 2.17 0.85 0.34 0.73 0.38 Sex GenImbal 7.72** 0.17 0.83 0.01 0.47 0.10 2.35 0.25 0.21 1.16

4 0.87b .047 1.04 1.90 1.24 1.38 G x AGd Note. Superordinate Behaviors are Humiliation, Violence/Aggression, Sex and Gender Role Imbalances. Multivariate F ratios were generated from Pillais statistic. *p < .05.

aMultivariate bMultivariate cUnivariate dUnivariate ***