Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Identity Case Study - How Is National Identity Symbolized

Uploaded by

suekoaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

National Identity Case Study - How Is National Identity Symbolized

Uploaded by

suekoaCopyright:

Available Formats

National Identity case study: How is national identity symbolized?

AAG Center for Global Geography Education

Learning Objectives

By completing this case study, you will be able to:

1. Explain why specific places come to symbolize national identity in varied contexts, 2. Give examples of how icons of national identity are socially reproduced by political actors.

Introduction

In this case study, you will gain some insight into the emotional and geographical dimensions of nationalism by examining some of the ways people in different places express pride and love for their nation.

Nationalism can inspire strong feelings of loyalty and devotion to a political cause, idea, or movement, often through the use of symbols and slogans. Symbols of nationalism are depicted in flags, works of art, national anthems, architecture, currency, postage stamps, passports, and many other forms of media. These symbols reinforce a national consciousness, create a sense of pride toward national culture, and inspire loyalty toward national political interests. K. R. Minogue examined this phenomenon in his book Nationalism (1967). He states that "flags and anthems can be used to create members of a nation by developing new habits and emotions; the "Star spangled banner [U.S. flag] with its stars increasing as a new state joined the Union was an important symbol of America for the millions of immigrants to the United States" (Minogue 1967: 11).

The flag of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) featured two images evoking the working class -- the hammer (industry) and the sickle (agriculture). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly independent nations in Eastern Europe and Central Asia removed the hammer-and-sickle symbol from their redesigned flags.

Pause and Reflect 1: Examine the flags of Estonia, Armenia, and Uzbekistan (Figures 1-3). What changes do you observe?

Figure 1a. Flag of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (1953-1989)

Figure 1b. Flag of Estonia (1918-1940 and 1990-Present)

Figure 2a. Flag of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (1952-1990)

Figure 2b. Flag of Armenia (1918-1940 and 1990-Present)

Figure 3a. Flag of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (1952-1990)

Figure 3b. Flag of Uzbekistan (1990-Present)

Image Source: FOTW Flags Of The World website at http://flagspot.net/flags/

Back to main menu

Suggested citation: Webster, G. and Luna Garcia, A. 2010. National Identity case study: How is nationalism symbolized? In Solem, M., Klein, P., Muiz-Solari, O., and Ray, W., eds., AAG Center for Global Geography Education. Available from http://globalgeography.aag.org.

Iconography

States employ iconography to build a sense of commonality, or "nation." Conceptually developed by renowned French geographer Jean Gottmann (1951, 1952), a state's iconography includes emotive symbols used to define a state's identity and image. A state's political coherence and even stability may be improved through the effective use of such symbols. Among these may be the state's name, flag, buildings and monuments, notable heroic personalities, historical events and sites, symbols of national identity as portrayed on coins, stamps and official documents, athletic teams and primary cultural attributes such as

religion and language. For example, many countries include in their names words such as "Democratic," "Republic," "People's," "Commonwealth," "Popular," and "United" to convey a positive image both inside and outside the country. And clearly the populations of some states view their national flags with nearreligious reverence, and take great pride in the accomplishments of athletic teams representing the country. While Brazil, for example, is composed of many different ethnic groups, when their national soccer team does well in international competition, there is a resulting sense of collective national pride in being "Brazilian" (Webster 2006).

The elements of a state's iconography constitute the symbolic "glue" around which a population develops a sense of common identity, a particularly important effort in multinational states when one considers now divided former states like Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. From this sense of identity develops patriotism or nationalism, resulting in public support for the state. Support may be expressed in a variety of ways, including adherence to laws and legal institutions, payment of taxes, and military service. In return the population gains a sense of identity and commonality with other members of the nation, or nations. Because states are commonly associated with specific geographic areas, a sense of statehood can further promote a "sense of place." These senses of commonality are transmitted across generations through the family unit, the school system and other political, social, religious or economic institutions. The success of this generational reproduction of identification with a state's iconography can contribute to its stability and longevity.

Back to main menu

Centrifugal and Centripetal Forces

Another prominent political geographer, Richard Hartshorne (1950), argued that the integration of a state's territory involves two competing types of forces: centrifugal forces that pull populations apart, and centripetal forces that pull populations together. Centrifugal forces can include physical features such as water bodies, mountain ranges or sheer areal size and distances that limit interaction by the state's population. Human dimensions such as differences in religious belief, culture, and economic activity can also act as centrifugal forces. These forces can limit interaction, producing regionalism and creating dissimilarity among groups of citizens within a state. Under such circumstances, what stops a state from falling apart? If a state is to exist in a stable form, there must be centripetal forces of greater magnitude than the existing centrifugal forces. A well-developed national iconography can be a central element of these centripetal forces.

Hartshorne also suggested that the preeminent centripetal force a state must develop is a "reason for existing," or a raison d' etre. The raison d' etre for a particular state might be to create a homeland for its nation. Other such foundations might be religious or political freedom. A state without a raison d' etre may lose its relevancy to the population, which in turn may lead some in the groups to seek political or geographic changes to the state.

Pause and Reflect 2: Identify the centrifugal and centripetal forces acting in your state. In what ways does your state utilize centripetal forces? In what ways does your state counter centrifugal forces?

Back to main menu

Iconography in the European Union

National symbols convey different messages. Symbols of inclusion communicate a desire to incorporate multiple groups of people whereas symbols of exclusion indicate a desire to separate one group from another.

New political realities are often challenged with the choice of a symbol, a national day, or an anthem that represents all the citizens of that territory. Since 1992, the European Union (EU) has worked quite hard to obtain a general consensus on the symbols that represent this new supranational institution.

One of these symbols is the official flag of the EU. It is a blue flag with 12 yellow stars. Created in 1955 for the European Council, it was adopted later as the official flag of the European Commission. The flag was originally designed by the Council of Europe, which holds the copyright for the flag. However the Council of Europe agreed that the European Communities could use the flag and promoted its use by other regional organizations after it was created. The Council of Europe now shares responsibility with the European Commission for ensuring that use of the symbol respects the dignity of the flag - taking measures to prevent misuse of it.

Symbols can be controversial and create conflicts among different groups within the same territory. As you can see on this Wikipedia page, even the flag of Europe created some discussions around the numbers of stars that should be used in the flag.

Back to main menu

Iconography in the European Union

Another important symbolism appears in the Euro Bank notes and coins. When the new European currency was adopted in 2002, it created a new challenge for the European legislators. This time, they needed to design a currency that represented the 12 countries that first joined the Euro zone (Ireland, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, Portugal, Austria, Finland, Greece, France, Italy, and Germany). Three EU member states of that time chose not to join the Euro zone: the UK, Denmark, and Sweden. Besides important economic reasons, these three states declared that their currency was an important symbol of their nation, and they were also reticent to adopt the Euro currency because they believed it was a form of relinquishing national sovereignty to the EU.

For the Europeans, the challenge of designing the new currency was important because it was a great opportunity to create something to symbolize a supranational European identity. The new currency also needed to have a flexible symbolism that could be adapted to future expansions of the currency in Europe. (By 2008, three new countries have joined the Euro-zone: Slovenia, Malta and Cyprus; Slovakia formally adopted the euro at the start of 2009.)

The currency designers ultimately chose to use national symbols only in the coins, while creating a unified design for the banknotes. The adopted design used unidentified bridges and windows from different architectural moments. These symbols are generic, in that they cannot be identified with any particular country and yet are recognizable for almost all the countries in Europe or at least for those of western and southern Europe that share a Greek and Roman legacy.

The EU designed the notes and coins of their new euro currency so as to express a sense of cooperation, communication, and openness (Figure 4). The euro coins also display symbols promoting the idea of unity among several European states (the bridges) and the openness of the process (the windows). But notice how the design of the coins left some space to maintain national representation and symbols. Each euro coin has one side that symbolizes the member State that issued the coin. For example, a 2-euro coin issued in Spain includes the portrait of King Juan Carlos 1 de Borbon y Borbon, King of Spain (Figure 5). The euro coins can be used in any of the EU member States, no matter where the coin was issued. Check the euro coins and analyze the symbols that each country has decided to use, for example the Netherlands, Italy, France or Spain. What do you think they wanted to emphasize?

Figure 4. Front and Back of the 5 Euro Note

Figure 5. The common European side of the 2 Euro coin (left) and the Spanish motif side (right)

Image sources for Figure 4 and 5: http://www.eucoins.info/wp-

content/uploads/image/two%20Euro%20coin.jpg, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2_euro_coin_Es_serie_1.png

Pause and Reflect 3: Discuss among your class whether you think the European Union made the right decision about the symbolism of the euro currency. Are these symbols inclusive or exclusive? If exclusive, which countries in Europe are not represented?

Back to main menu

Patriotism, Nationalism, and Banal Nationalism

There is a massive and growing literature on both patriotism and nationalism, and more recently on banal nationalism. Many social scientists view patriotism and nationalism as distinct in terms of historical development, their association with nations or states, and their characteristics. For example, Alter (1985) argues that patriotism is an older concept pertaining to "love of one's homeland" while nationalism is comparatively new and associated with the development of nation-states in the nineteenth century. Similarly, Hutchinson and Smith (1994) trace patriotism to the Greek and Roman Empires, but tie the development of nationalism to the American and French Revolutions of the late eighteenth century.

Some social scientists argue that patriotism is associated with the state, while nationalism is associated with the nation. For example, Taylor (1999: 228-29) argues that nationalism is associated with an "ethnic, linguistic, cultural or religious identity," while patriotism is "a strong sense of identity with the polity." Grosby (2005: 16-7) similarly argues that patriotism is simply "loyalty to a territorial community," while nationalism highlights one's nation relative to all other nations, creating "warring camps" and a "repudiation to civility and tolerance for difference."

Still other social scientists view patriotism and nationalism along a continuum of intensity. Kedourie (1994: 49-50), for example, defines patriotism as simply "affection for one's country," while nationalism adds "xenophobia" (hatred of foreigners), creating an "us versus them" mentality. Many authors view nationalism as irrational, fanatical, xenophobic and aggressive, while viewing patriotism simply as love of country. Regardless of how one defines patriotism and nationalism, both rely on the promotion of a state's iconography.

In the past two decades many social scientists have questioned whether there is any difference between patriotism and nationalism. This fascinating debate was spawned by the publication of Michael Billig's 1995, book, Banal Nationalism. Billig (1995: 6) argues that those in the developed countries commonly understand nationalism as a problem in the developing world, with only intermittent cases in which it rises in the states of the West. He argues that between such intermittent events the "ideological foundations" of the developed countries are maintained by "banal nationalism," or the nationalism of everyday life. He defines banal nationalism as the (Billig 1995: 6):

Ideological habits which enable the established nations of the West to be reproduced . life . . . . citizenry. . . . these habits are not removed from everyday

Daily, the nation is indicated, or 'flagged', in the lives of its Nationalism, far from being an intermittent mood in established

nations, is the endemic condition.

Billig (1995: 7) also argues that the term "banal" does not mean that this type of nationalism is harmless. Rather banal nationalism creates a reservoir of emotional attachment to the state that can be mobilized and manipulated "without lengthy campaigns of political preparation." Webster (2011) has employed the concept of banal nationalism to suggest how the population of the United States was drawn into the war in Iraq without a credible evidence of its role in international terrorism. Similarly, Billig (1995:1-5) argues that banal nationalism allowed the Thatcher government in Great Britain to rapidly respond to the invasion of the Falkland Islands by Argentina in 1982, with little or no opposition.

Back to main menu

The New Iconography of Kosovo I

The Balkans of southeastern Europe have long suffered from periodic flare ups of ethnic nationalism, particularly in the former state of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was formed as WWI hostilities were ending in 1918. After WWII, Yugoslavia became a communist republic lead by Josip Broz Tito, the leader of the Yugoslav Partisans, a guerilla group who fought against the Nazis. Tito led Yugoslavia from 1943 until his death in 1980, and was able to limit the outbreaks of ethnic nationalism. At his death Yugoslavia had 6 republics (Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina) and two autonomous provinces (Kosovo, Vojvodina), both located in the Serbian republic.

After Tito's death, ethnic conflict and nationalism increased in Yugoslavia, most particularly after the demise of the former Soviet Union in January 1991, and the creation of 15 new countries from its republics. By the middle of 1991, both Slovenia and Croatia had declared their independence from Yugoslavia. In January, 1992, Macedonia declared its independence, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina in April of 1992. These declarations of independence were met with armed conflict and thousands of deaths, most particularly in the Bosnian War. Systematic rape was also used in the Bosnian War, particularly against Muslim women. As many as 50,000 women may have been victims. With the secession of these four republics, Serbia and Montenegro formed the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in April 1992.

As noted above, Kosovo was an autonomous province in the Serbian republic. In 1389 Ottoman forces defeated a combined force of Serbs, Albanians and Bosnians in the Battle of Kosovo, subsequently leading to the formal incorporation of Serbia into the Ottoman Empire in 1455. The battle became a rallying point for Serbs, and Kosovo itself central to Serbian identity with the battle remembered as a heroic and honorable effort against insurmountable forces. Control by the Ottomans further increased the Muslim population in Christian Orthodox Serbia, and particularly in Kosovo which today is over 90 percent Albanian Muslim.

In 1990, Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic revoked Kosovo's autonomous status and imposed a number

of repressive policies that had negative repercussions on the province's economy and ability to function. In response, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) began a series of attacks in 1996 on Serbian authorities and interests. This led Milosevic to send Serbian troops into Kosovo, resulting in a guerilla war with the KLA. The conflict escalated and resulted in thousands of deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. By early 1999, NATO announced its intention to intervene against Serbian forces if hostilities were not halted. In spite of the threat, attacks continued and NATO began a ten week offensive against Serbian forces on forces on March 22, 1999.

Milosevic capitulated in early June, 1999. A NATO led force (KFOR) then entered Kosovo to provide security while Kosovo's governance was transferred to the United Nations. On February 17, 2008, the Kosovo Assembly declared its formal independence from Serbia, and today it is recognized by approximately 70 countries including the United States, France, United Kingdom, Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro and Macedonia. Kosovo's independence is not recognized by Serbia, which continues to view the former province as central to Serbian territory and identity.

Back to main menu

The New Iconography of Kosovo II

As noted earlier, national flags can be highly emotive elements of a state's iconography. Because most of the population of Kosovo is Albanian, the flag of Albania was sometimes used prior to independence as the Kosovo flag, though clearly Serbian authorities viewed this as provocative. After KFOR entered Kosovo, the UN flag was commonly flown in Kosovo. The organization's regulations required that if the Albanian flag was flown, it be next to the Serbian flag, a requirement that was not commonly followed (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Flags of Albania (left) and Serbia (right)

As is the norm with newly emerging states, in February 2008, Kosovo adopted a new flag and coat of arms, followed by a national anthem in June. The flag resulted from an international competition organized by the Kosovo Unity Team and received nearly 1,000 submissions (Figures 7 and 8). The competition's guidelines required that the winning selection underscore the diverse population of Kosovo, and avoid substantial imitation of either the Serbia or Albanian flags. For example, the resulting flag could not include the Albanian or Serbian double-headed eagle (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 7. Dardania flag. One of the proposed flags for Kosovo

Figure 8. Another proposed flag for Kosovo

Figure 9. The Albanian flag used by the secessionist state Republic of Kosovo proclaimed in 1991 by a parallel parliament representing the Ethnic Albanian population of Kosovo

Figure 10. This flag was the official flag of the Albanian ethnic minority of Yugoslavia from the late 1940s to the late 1980s

The winning selection was blue with a gold map of Kosovo at the flag's center (Figure 11). Notably, only Cyprus has an outline of its territory on its flag. Given territorial additions and deletions to states in the Balkans over the past few centuries, such a presentation enshrines Kosovo's territorial dimensions in an official and repetitive manner. Above the map of Kosovo are six white stars to represent Kosovo's largest ethnic communities. These include the Albanians, Serbs, Roma, Bosniaks, Turks and Macedonians. Notably, while Kosovo's population is estimated at approximately 2 million people, Albanians constitute 92%, with Serbs being the second largest group at only 4%.

Figure 11. Official flag of Kosovo, adopted 2008

Kosovo's coat of arms is in the shape of a shield and reproduces the flag's design encircled by a gold border. As a result, citizens seeing either the flag or coat of arms will see both an outline map of Kosovo, and the six stars representing the six largest ethnic groups. This underscores the frequently repetitive nature of building a sense of commonality or nation. Finally, Kosovo's national anthem was selected by its legislative branch in a competition as well. The winning submission was by Kosovar Albanian composer, Mendi Mengjigi, and is entitled "Europe." Entries were not to promote any one group over others, and the anthem currently has no words. As stated by BBC reporter Helen Fawkes (2008), "For the authorities, it is a crucial part of nation building and is something which is designed to unite the people of Kosovo."

It remains to be seen whether the new Republic of Kosovo's flag, coat of arms and anthem will be successful elements of the country's iconography and provide the "symbolic glue" to form a cohesive population. But in February 2008, the flag was first used to represent Kosovo by its team participating at the World Team Table Tennis Championships in Beijing, People's Republic of China (PRC). The PRC does not recognize Kosovo as an independent country. It is notable that just as Serbia views Kosovo as a breakaway province, the PRC views the Republic of China (Taiwan) as a breakaway subdivision, though it too has its own flag.

Back to main menu

Capital Cities as Iconography

In many countries, iconographic buildings, memorials and statues are concentrated in the capital city. This concentration frequently aids in the definition and promotion of a national culture with its accompanying set of national symbols. In the minds of foreign nationals it may be nearly impossible to separate France from Paris, Great Britain from London, Russia from Moscow, or Mexico from Mexico City - in short, these cities have long been not only the political and economic control centers for their respective countries, but also the progenitors of the national cultures of these states.

Few cities in the world are as important to their country's history and sense of nation as Berlin is to Germany (Figure 12). Berlin was Germany's capital from the time of German unification in the midnineteenth century until World War II. After Germany's surrender in 1945, the country was divided between the occupation zones of the three Western Allies including the United States, Great Britain and France, and the occupation zone of the former Soviet Union (Pounds 1962). Eventually, two separate countries emerged with the Soviet sector becoming the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the three western zones becoming the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).

Figure 12. Berlin Map

Though Berlin was located in the zone of Soviet occupation, it was also subdivided into four zones as seen on this map. The Soviet sector of Berlin became the capital of the GDR, or East Germany, while the city of Bonn became the capital of the FRG. The selection of the comparatively small city of Bonn as the capital of the FRG was in the beginning expected to be temporary, with eventual relocation back to Berlin. Bonn's selection was further in part due to the near-total destruction of larger and better-known cities in the FRG such as Cologne and Frankfurt that had been the targets of Allied bombs during the war (Pounds 1962).

The zones of the three western allies in Berlin, France, Great Britain and the United States, were all but merged to form "West Berlin," an enclave of West Germany entirely circled by East German territory. The enclave survived as a portion of the FRG with great effort on the part of the West Germans and the western Allies. Possibly the most notable example were the efforts by the U.S. and Great Britain during the Berlin Airlift in 1948 when the Soviets prevented land access to the city and thousands of plane loads of goods were flown into the enclave. The U.S. Army Commander in Germany at the time suggested that if Berlin fell to the Soviets, communism would make its way into West Germany and then the European continent as a whole (Short 1982). As a result, Berlin was also symbolic to western allies in their efforts to limit further territorial expansion by the former Soviet Union.

The division between the eastern and western portions of the city was reinforced in August of 1961 when the Berlin Wall was erected by the GDR, preventing free movement between the two segments. It was not until 28 years later, on November 9, 1989, that the first holes were cut in the Berlin Wall, with large sections dismantled in subsequent weeks. One year later, East Germany and West Germany were formally reunited. In June 1991 the decision to move the capital of the reunified Germany back to Berlin was made. By the time the move was completed in 2000, the government had spent over $13 billion. The total amount of money invested in the rebuilding of Berlin was estimated at $135 billion - "the most ambitious urban-renewal project ever undertaken" (Range 1996).

To fully understand the basis for the willingness of the German government and people to underwrite such a cost, one must understand Berlin not only as an important city, but also the city's symbolic importance to the German nation and state. As stated by German geographer Mechtild Rossler (1994: 94), "The history of Berlin represents the history of the Germans, the nation [e.g., state] as well as the people." Berlin was founded in the 13th century, and it served as a market town early in is history. Later it became the city of residence for the Brandenburgs, and its significance grew with them and as the capital of the powerful Prussian state. In 1871, Berlin was named the capital of the new German Reich, and it rapidly became the most important city in Central Europe. Adolph Hitler viewed "Berlin as the centre of Europe and the World, [and] wanted to create a city to signify visually the power of the Nazis" (Rossler 1994: 94). For example, Berlin hosted the 1936 Olympic Games and $25 million was invested in the city in preparation. The Olympic Stadium built by the Nazis seated 110,000 spectators and was the largest sports venue in the world at the time (Webster 2006).

Because Berlin was the site of Hitler's bunker and served as the German High Command Center during World War II, the city suffered substantial bomb damage during the war. Berlin was also a focal point in the Cold War. It therefore received early and significant rebuilding on both sides of the Berlin Wall. The substantial open space created by the removal of the Wall made real estate available for development. A rebuilt and reunified Berlin is intended to serve as symbolic of a new, reunified German state. As a result, in the late 1990s Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder labeled the post-reunification era in Germany as the "Berlin Republic" to "symbolize" a state "that has a democratic capital and is trying to connect to its democratic past" (Sahl 1999: A19).

Back to main menu

References

Alter, P. 1985. Nationalism. New York: Edward Arnold. Billig, M. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage. Bradley, J. 2000. Flags of our Fathers. New York: Bantam Books. Eriksen, T. H. and R. Jenkins, eds. 2008. Flag, Nation and Symbolism in Europe and America, London: Routledge. Fawkes, H. 2008. "Kosovo Celebrates 'Dream Come True'," BBC News, 17. February: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7249905.stm. Glassner, M.I. and H. de Blij. 1989. Systematic Political Geography. New York: John Wiley. Gottmann, J. 1951. Geography and International Relations. World Poltics 3: 153-173. Gottmann, J. 1952. The Political Partitioning of Our World: An Attempt at Analysis. World Politics 4: 513-

519. Grosby, S. 2005. Nationalism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Hartshorne, R. 1950. "The Functional Approach in Political Geography, " Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 40: 95-130. Hutchinson, J. and A.D. Smith, eds. 1994. Nationalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Janowitz, J. 1983. The Reconstruction of Patriotism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. In Nationalism, edited by J. Hutchinson and A.D.

Kedourie, E. 1994. Nationalism and Self-Determination. Smith, 49-55. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Minogue, K.R. 1967. Nationalism. London: Batsford.

Pounds, N.J.G. 1962. Divided Germany and Berlin. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand. Pounds, N.J.G. 1963. Political Geography. New York: McGraw Hill. Pounds, N.J.G. and Ball, S.S. 1964. "Core Areas and the Development of the European States System," Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 54: 24-40. Range, P.R. 1996. "Reinventing Berlin," National Geographic, December: 96-117. Rossler, M. 1994. "Berlin or Bonn? National Identity and the Question of the German Capital," in D. Hooson (ed.), Geographical and National Identity, Oxford, UK: Blackwell, pp. 92-103. Sahl, R.D. 1999. "10 Years After the Wall: A New Berlin," Boston Globe, 6 November: A19. Short, J.R. 1982. An Introduction to Political Geography. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Snyder, L.L.1976. Varieties of Nationalism: Comparative Study. Hinsdale, IL: Dryden Press. Taylor, C. 1999. Nationalism and Modernity. In Theorizing Nationalism, edited by R. Beiner, 219-246. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Webster, G. 2006. Sports, Community, Nationalism and the International State System. In The Geography-Sports Connection: Using Sports to Teach Geography, edited by L. DeChano and F. Shelley, 33-46, Pathways Series No. 33. Jacksonville, AL: National Council for Geographic Education. Webster, G. and T. Kidd. 2002. Globalization and the Balkanization of States: The Myth of American Exceptionalism. Journal of Geography 101(2): 73-80. Webster, G. 2006. Sports, Community, Nationalism and the International State System. In The Geography-Sports Connection: Using Sports to Teach Geography, edited by L. DeChano and F. Shelley, 33-46, Pathways Series No. 33. Jacksonville, AL: National Council for Geographic Education. Webster, Gerald R. 2011. American Nationalism and the Invasion of Iraq. Geographical Review, forthcoming.

You might also like

- Flag ListDocument21 pagesFlag ListDurai NarashimmanNo ratings yet

- Re-Mapping Centre and Periphery: Asymmetrical Encounters in European and Global ContextsFrom EverandRe-Mapping Centre and Periphery: Asymmetrical Encounters in European and Global ContextsTessa HauswedellNo ratings yet

- National Culture and European CultureDocument5 pagesNational Culture and European CulturemihamimyNo ratings yet

- Cultural Borders of Europe: Narratives, Concepts and Practices in the Present and the PastFrom EverandCultural Borders of Europe: Narratives, Concepts and Practices in the Present and the PastNo ratings yet

- The Resurgence of Nationalism in The EuropeanDocument11 pagesThe Resurgence of Nationalism in The Europeanberman100No ratings yet

- Europe in Its Own Eyes, Europe in the Eyes of the OtherFrom EverandEurope in Its Own Eyes, Europe in the Eyes of the OtherNo ratings yet

- Nation Building in Yugoslavia ModelDocument11 pagesNation Building in Yugoslavia ModelCharlène AncionNo ratings yet

- The Szekler Identity in Romania After 1989... Pp. 218-228Document11 pagesThe Szekler Identity in Romania After 1989... Pp. 218-228Magyari Nándor LászlóNo ratings yet

- IELTS Academic Training Reading Practice Test #4. An Example Exam for You to Practise in Your Spare TimeFrom EverandIELTS Academic Training Reading Practice Test #4. An Example Exam for You to Practise in Your Spare TimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- +"nationalism and Homophobia in Central and Eastern EuropeDocument22 pages+"nationalism and Homophobia in Central and Eastern EuropeMishiko OsishviliNo ratings yet

- The Strange Case of the Hague Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: 2nd edition of the International “Giuseppe Torre” AwardFrom EverandThe Strange Case of the Hague Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: 2nd edition of the International “Giuseppe Torre” AwardNo ratings yet

- How Nation-States Create and RespondDocument22 pagesHow Nation-States Create and RespondSofía G.No ratings yet

- Helleiner - National Identities An National CurrenciesDocument29 pagesHelleiner - National Identities An National CurrenciesMatilda PopaNo ratings yet

- Commemorative Stamps As A Recognition Tool A CrossDocument23 pagesCommemorative Stamps As A Recognition Tool A CrossDr. Vinay PatelNo ratings yet

- Brunn (2011) STAMPS AS MESSENGERS OF POLITICAL TRANSITIONDocument19 pagesBrunn (2011) STAMPS AS MESSENGERS OF POLITICAL TRANSITIONMartenNo ratings yet

- Who Are EuropeansDocument43 pagesWho Are EuropeansI have to wait 60 dys to change my nameNo ratings yet

- Regionalism and Collective IdentitiesDocument21 pagesRegionalism and Collective Identities14641 14641No ratings yet

- Nation State v. State NationDocument20 pagesNation State v. State NationOscar Atkinson100% (1)

- Ifversen Myth & History PoliticsDocument51 pagesIfversen Myth & History Politicschris68197No ratings yet

- Black 2018 B Uploaded VersionDocument46 pagesBlack 2018 B Uploaded VersionOwais AhmedNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Economics - 2020 - Almagro - The Construction of National IdentitiesDocument48 pagesTheoretical Economics - 2020 - Almagro - The Construction of National IdentitiesANA PAOLA HUESCA LOREDONo ratings yet

- Collective IdentityDocument3 pagesCollective IdentityNatalia StincaNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and Identity Politics in The Balkans Greece and The Mace Don Ian QuestionDocument45 pagesNationalism and Identity Politics in The Balkans Greece and The Mace Don Ian QuestionMeltem Begüm SaatçıNo ratings yet

- Victor Roudometof: Nationalism and Identity Politics in The Balkans: Greece and The Macedonian QuestionDocument46 pagesVictor Roudometof: Nationalism and Identity Politics in The Balkans: Greece and The Macedonian QuestionHistorica VariaNo ratings yet

- Curs Cu PecicanDocument6 pagesCurs Cu PecicanDianaIoanaNo ratings yet

- 01-08-2022-1659354601-6-Impact - Ijrhal-7. Ijrhal - Separatist Regions in Western Europe and Their Geopolitical Impact On The European UnionDocument16 pages01-08-2022-1659354601-6-Impact - Ijrhal-7. Ijrhal - Separatist Regions in Western Europe and Their Geopolitical Impact On The European UnionImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Nationalism by K. A. CeruloDocument5 pagesNationalism by K. A. CeruloAaron DamianNo ratings yet

- Mes Que Un Club Football Nationalism andDocument28 pagesMes Que Un Club Football Nationalism andEuclides FreitasNo ratings yet

- The Euro and European Identity: Symbols, Power and The Politics of European Monetary Union.Document28 pagesThe Euro and European Identity: Symbols, Power and The Politics of European Monetary Union.reniestessNo ratings yet

- Collective IdentityDocument11 pagesCollective IdentityZsuzsanna TorokNo ratings yet

- 00 Isaacs, Rico Polese, Abel - Between "Imagined" and "Real" Nation-Building - Identities and Nationhood in Post-SovietDocument13 pages00 Isaacs, Rico Polese, Abel - Between "Imagined" and "Real" Nation-Building - Identities and Nationhood in Post-SovietcetinjeNo ratings yet

- What Were The Factors Shaping National Identity in Europe After 1789Document7 pagesWhat Were The Factors Shaping National Identity in Europe After 1789L GNo ratings yet

- Jeroen Moes - European Identity Compared (Final)Document31 pagesJeroen Moes - European Identity Compared (Final)damaneraNo ratings yet

- W5yxsLlytEys3RgoG5tGWNbfyis PDFDocument35 pagesW5yxsLlytEys3RgoG5tGWNbfyis PDFMaryam مريمNo ratings yet

- National IdentityDocument236 pagesNational Identitylixiaoxiu100% (9)

- Art and Museum in International RelationsDocument15 pagesArt and Museum in International RelationsAnanya KNo ratings yet

- The Magic of The National Ag: Ethnic and Racial Studies February 2016Document20 pagesThe Magic of The National Ag: Ethnic and Racial Studies February 2016brainhub50No ratings yet

- Ethnicracial ArticleDocument46 pagesEthnicracial ArticleDomnProfessorNo ratings yet

- GT Chapter 1Document52 pagesGT Chapter 1Yared AbebeNo ratings yet

- The Euro Between National and European IdentityDocument20 pagesThe Euro Between National and European IdentityI have to wait 60 dys to change my nameNo ratings yet

- Akturk - 18-11-2015 European State Formation and Three Models of Nation-BuildingDocument41 pagesAkturk - 18-11-2015 European State Formation and Three Models of Nation-BuildingAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Nationalism in EducationDocument9 pagesNationalism in EducationdocumentsattilaNo ratings yet

- 06 Menga, Filippo - Building A Nation Through A Dam - The Case of Rogun in TajikistanDocument17 pages06 Menga, Filippo - Building A Nation Through A Dam - The Case of Rogun in TajikistancetinjeNo ratings yet

- QaaoDocument46 pagesQaaonastia.grijalva0No ratings yet

- A Glance To Nationalism Reflections and Solutions in BalkansDocument35 pagesA Glance To Nationalism Reflections and Solutions in BalkansMarco De MarchiNo ratings yet

- Yugo Nostalgia Cultural Memory and Media in The Former YugoslaviaDocument19 pagesYugo Nostalgia Cultural Memory and Media in The Former YugoslaviaGeno GoletianiNo ratings yet

- Cultivating A Sense of Nationalism and Affection For The CountryDocument4 pagesCultivating A Sense of Nationalism and Affection For The CountryHan LimNo ratings yet

- Reading The Map of The Middle EastDocument12 pagesReading The Map of The Middle EastMartin Kramer100% (1)

- Documentos de Trabajo: Universidad Del Cema Buenos Aires ArgentinaDocument58 pagesDocumentos de Trabajo: Universidad Del Cema Buenos Aires Argentinaserafo147100% (1)

- Langlois IdentityDocument10 pagesLanglois IdentityNicolauNo ratings yet

- Competitive NationalismCompetitive Nationalism: State, Class, and The Forms of Capital in Devolved ScotlandDocument17 pagesCompetitive NationalismCompetitive Nationalism: State, Class, and The Forms of Capital in Devolved ScotlandVariantMagNo ratings yet

- Culture Wars Serbian History Textbooks ADocument10 pagesCulture Wars Serbian History Textbooks AXDNo ratings yet

- Othering or Left BehindDocument44 pagesOthering or Left BehindmamaNo ratings yet

- Nation BuildingDocument16 pagesNation BuildingCAnomadNo ratings yet

- Laffan - 1996 - The Politics of Identity and Political Order in EUDocument22 pagesLaffan - 1996 - The Politics of Identity and Political Order in EUMark Friis McHauNo ratings yet

- DR Petra Zimmermann-Steinhart-creating Regional Identities PDFDocument16 pagesDR Petra Zimmermann-Steinhart-creating Regional Identities PDFBakos BenceNo ratings yet

- The Wide Angle - Predictions of A Rogue DemographerDocument16 pagesThe Wide Angle - Predictions of A Rogue DemographersuekoaNo ratings yet

- Compatibility Between The Sharia and Human RightsDocument7 pagesCompatibility Between The Sharia and Human RightssuekoaNo ratings yet

- Domain of Ideologies 1 The ParadoxDocument150 pagesDomain of Ideologies 1 The ParadoxsuekoaNo ratings yet

- From Argument To AssertionDocument22 pagesFrom Argument To AssertionsuekoaNo ratings yet

- Deep Hole Drilling Tools: BotekDocument32 pagesDeep Hole Drilling Tools: BotekDANIEL MANRIQUEZ FAVILANo ratings yet

- rp10 PDFDocument77 pagesrp10 PDFRobson DiasNo ratings yet

- Chhay Chihour - SS402 Mid-Term 2020 - E4.2Document8 pagesChhay Chihour - SS402 Mid-Term 2020 - E4.2Chi Hour100% (1)

- The Covenant Taken From The Sons of Adam Is The FitrahDocument10 pagesThe Covenant Taken From The Sons of Adam Is The FitrahTyler FranklinNo ratings yet

- BrochureDocument3 pagesBrochureapi-400730798No ratings yet

- Pityriasis VersicolorDocument10 pagesPityriasis Versicolorketty putriNo ratings yet

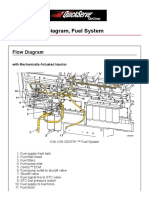

- Cummin C1100 Fuel System Flow DiagramDocument8 pagesCummin C1100 Fuel System Flow DiagramDaniel KrismantoroNo ratings yet

- Friction: Ultiple Hoice UestionsDocument5 pagesFriction: Ultiple Hoice Uestionspk2varmaNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument1 pageDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesJonathan CayatNo ratings yet

- Applications SeawaterDocument23 pagesApplications SeawaterQatar home RentNo ratings yet

- Economic Review English 17-18Document239 pagesEconomic Review English 17-18Shashank SinghNo ratings yet

- Pathology of LiverDocument15 pagesPathology of Liverערין גבאריןNo ratings yet

- LP For EarthquakeDocument6 pagesLP For Earthquakejelena jorgeoNo ratings yet

- 2022 WR Extended VersionDocument71 pages2022 WR Extended Versionpavankawade63No ratings yet

- Sources of Hindu LawDocument9 pagesSources of Hindu LawKrishnaKousikiNo ratings yet

- Latched, Flip-Flops, and TimersDocument36 pagesLatched, Flip-Flops, and TimersMuhammad Umair AslamNo ratings yet

- Lecture 14 Direct Digital ManufacturingDocument27 pagesLecture 14 Direct Digital Manufacturingshanur begulaji0% (1)

- LSCM Course OutlineDocument13 pagesLSCM Course OutlineDeep SachetiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 23Document9 pagesChapter 23Javier Chuchullo TitoNo ratings yet

- How He Loves PDFDocument2 pagesHow He Loves PDFJacob BullockNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cardiac Disease: A Guide To Evaluation, Treatment and Anesthetic ManagementDocument87 pagesCongenital Cardiac Disease: A Guide To Evaluation, Treatment and Anesthetic ManagementJZNo ratings yet

- QuexBook TutorialDocument14 pagesQuexBook TutorialJeffrey FarillasNo ratings yet

- Progressive Muscle RelaxationDocument4 pagesProgressive Muscle RelaxationEstéphany Rodrigues ZanonatoNo ratings yet

- Wner'S Anual: Led TVDocument32 pagesWner'S Anual: Led TVErmand WindNo ratings yet

- Miguel Augusto Ixpec-Chitay, A097 535 400 (BIA Sept. 16, 2013)Document22 pagesMiguel Augusto Ixpec-Chitay, A097 535 400 (BIA Sept. 16, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- C2 - Conveyors Diagram: Peso de Faja Longitud de CargaDocument1 pageC2 - Conveyors Diagram: Peso de Faja Longitud de CargaIvan CruzNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFmirthafoucault100% (8)

- Escaner Electromagnético de Faja Transportadora-Steel SPECTDocument85 pagesEscaner Electromagnético de Faja Transportadora-Steel SPECTEdwin Alfredo Eche QuirozNo ratings yet

- Siemens Make Motor Manual PDFDocument10 pagesSiemens Make Motor Manual PDFArindam SamantaNo ratings yet

- Biblical World ViewDocument15 pagesBiblical World ViewHARI KRISHAN PALNo ratings yet

- No Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesFrom EverandNo Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Kilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsFrom EverandKilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaFrom EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentFrom EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowFrom EverandHeretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (57)

- North Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and DefectorsFrom EverandNorth Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and DefectorsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017From EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (63)

- Palestine: A Socialist IntroductionFrom EverandPalestine: A Socialist IntroductionSumaya AwadRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017From EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (127)

- The Genius of Israel: The Surprising Resilience of a Divided Nation in a Turbulent WorldFrom EverandThe Genius of Israel: The Surprising Resilience of a Divided Nation in a Turbulent WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- Iran Rising: The Survival and Future of the Islamic RepublicFrom EverandIran Rising: The Survival and Future of the Islamic RepublicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (55)

- The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyFrom EverandThe Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyFrom EverandThe Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Plans For Your Good: A Prime Minister's Testimony of God's FaithfulnessFrom EverandPlans For Your Good: A Prime Minister's Testimony of God's FaithfulnessNo ratings yet

- The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the WarFrom EverandThe Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Ask a North Korean: Defectors Talk About Their Lives Inside the World's Most Secretive NationFrom EverandAsk a North Korean: Defectors Talk About Their Lives Inside the World's Most Secretive NationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (31)

- Unholy Alliance: The Agenda Iran, Russia, and Jihadists Share for Conquering the WorldFrom EverandUnholy Alliance: The Agenda Iran, Russia, and Jihadists Share for Conquering the WorldRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (16)

- Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower FutureFrom EverandParty of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower FutureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Somewhere Inside: One Sister's Captivity in North Korea and the Other's Fight to Bring Her HomeFrom EverandSomewhere Inside: One Sister's Captivity in North Korea and the Other's Fight to Bring Her HomeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (69)

- The Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of NeoliberalismFrom EverandThe Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of NeoliberalismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper's True Account of the Battle of RamadiFrom EverandThe Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper's True Account of the Battle of RamadiRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (139)

- The Gulag Archipelago: The Authorized AbridgementFrom EverandThe Gulag Archipelago: The Authorized AbridgementRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (491)