Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Election Law Cases (II)

Uploaded by

Nikki MendozaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Election Law Cases (II)

Uploaded by

Nikki MendozaCopyright:

Available Formats

ELECTION LAW CASES (II) PURISIMA V SALONGA ...

it is also true that in case of patent irregularity in the election returns, such as patent erasures and superimpositions in words and figures on the face of the returns submitted to the board, it is imperative for the board to stop the canvass of such returns so as to allow time for verification. A canvass and proclamation made withstanding such patent defects in the returns which may affect the result of the election, without awaiting remedies, is null and void. (Purisima v. Salonga, 15 SCRA 704).

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC DECISION December 5, 1940 G.R. No. L-47940 JUAN SUMULONG, in his capacity as president of Pagkakaisa ng Bayan (Popular Front Party), petitioner, vs. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTION, respondent. Office of the Solicitor-General Ozaeta and First

CAUTON V. COMELEC The purpose of the governing statutes on the conduct of elections [i]s to protect the integrity of elections to suppress all evils that may violate its purity and defeat the will of the voters. The purity of the elections is one of the most fundamental requisites of popular government. The Commission on Elections, by constitutional mandate, must do everything in its power to secure a fair and honest canvass of the votes cast in the elections. In the performance of its duties, the Commission must be given a considerable latitude in adopting means and methods that will insure the accomplishment of the great objective for which it was created to promote free, orderly, and honest elections. The choice of means taken by the Commission on Elections, unless they are clearly illegal or constitute grave abuse of discretion, should not be interfered with."8 [Cauton v. COMELEC, 19 SCRA 911 (1967)] It must be borne in mind that the purpose of governing statutes on the conduct of elections [i]s to protect the integrity of elections to suppress all evils that may violate its purity and defeat the will of the voters. The purity of the elections is one of the most fundamental requisites of popular government. The Commission on Elections, by constitutional mandate must do everything in its power to secure a fair and honest canvass of the votes cast in the elections. In the performance of its duties, the Commission must be given a considerable latitude in adopting means and methods that will insure the accomplishment of the great objective for which it was created to promote free, orderly and honest elections. The choice of means taken by the Commission on Elections, unless they are clearly illegal or constitute grave abuse of discretion, should not be interfered with.21 [Cauton v. COMELEC, 19 SCRA 911 [1967].] SUMULONG V COMELEC

Assistant Solicitor-General Reyes for respondent. N.V. Villarruz as amicus curiae. Laurel, J.: In a communication dated October 28, 1940, addressed to the respondent, the commission on Elections, the petitioner, Juan Sumulong, as head of the party denominated Pagkakaisa g Bayan (Popular Front Party), asks that said party be declared to be entitled to name the third election inspector in municipalities where it has candidates either for municipal or provincial officer in the forthcoming general election, although it had no candidates and did not obtain votes in those municipalities in the 1937 election. In this communication, the petitioner cites as a typical example the case of Bauan, Batangas, wherein Pagkakaisa g Bayan has candidates for the coming election but is denied by the municipal mayor of the said municipality the right to minority representation on the board of election inspectors, for the reason that it did not have any candidates and did not receive votes in the 1937 election. The said municipal mayor distributed the three election inspectors between the Nacionalista candidates, awarding the minority inspector to the minority faction of said party which opposed the other faction in the next preceding election. In the communication above referred to, the petitioner also alleged that in other provinces, namely, Abra, Agusan, Antique, Cagayan, Camarines Sur, Capiz, Davao, Ilocos Sur, Isabela, La Union Leyte, Marinduque, Masbate, Mindoro, Mt.

Province, Misamis Occidental, Negros Occidental, Negros Oriental, Nueva Vizcaya, Romblon, Surigao, Zambales, and Zamboanga, there are cases in which Pagkakaisa g Bayan finds itself in the same situation as that described in the example cited with respect to minority representation on the boards of election inspectors. On November 12, 1940, the respondent Commission rendered a decision denying the petition contained in the communication of October 28, 1940, the dispositive part of which reads as following: Teniendo en consideracion que la carta del Sr. Juan Sumulong, considerandola como una peticion formal, plantea ante esta Comision una cuestion de derecho sin referirse a ningun caso especifico ni alegar los hechos que sirvan de base, a su peticion, esta Comision es de opinion que no esta llamada a resolver cuestiones teoricas y de caracter general. Por tanto, se deniega la peticion. On November 18, 1940, the petitioner filed with the respondent Commission a motion for reconsideration alleging, that although his petition of October 28, 1940, covered municipalities in twenty three provinces, the case of Bauan, Batangas, was specified therein as a concrete case wherein Pagkakaisa g Bayan has been denied the right to name the third election inspector by the municipal mayor for the reason already stated. On November 29, 1940, the respondent Commission rendered a decision on the merits of the petition of the 28th of October, with particular reference to the municipality of Bauan, Batangas, in which the said petition was again denied on the following grounds: Section 70 of the Election Code provides, among other things, that two of the inspectors and the poll clerk and their substitutes shall belong to the party which polled the largest number of votes at the next preceding election, and the other inspector and his substitute shall belong to the party which polled the next largest number of votes at said election. In computing the number of votes polled by the parties, in case the appointment of inspectors is for a regular election of provincial and municipal offices the votes

polled by all the candidates of each party for said offices in themunicipality shall be counted, (Emphasis supplied.) Evidently, the law grants election in the municipality. Not having participated in the, regular election held in 1937 for provincial and municipal official, the Popular Front Party did not poll any lack of the basis prescribed in Section 70 of the Election Code, that is, the obtaining of votes constituting the next immediate place, said party, although national in character, is not entitled to the third inspector. The Popular Front Party having failed to establish its right to the inspectors, we now find ourselves confronted with the task of finding whether the third inspector was given to the correct party or not. The presiding officer of the municipal council of Bauan gave the third or minority inspector to a faction of the Nacionalista Party opposed to the other faction. Strictly speaking, under the express terms of Section 70 Code aforecited, neither a faction of, or group, affiliated to the Nacionalista Party, nor the Popular Front Party is entitled to the third or minority inspector in the municipality of Bauan. This is so because the faction of the Nationalista Party is not a political party within the contemplation of said Section 70: and the Popular Front Party, although it is national in character, and a political party within the contemplation of said Section 70 of the Election Code did not obtain any vote in the said municipality in the election held in 1937. Therefore, the present by the provisions of the Election Code, but is rather a case falling into that indiscriminate residue of matter not expressly covered by legislative enactment but must, in order not to paralyze the orderly functions of government be held to fall within the field of administrative discretion; and in the exercise of that administrative discretion, this Commission has chosen not to disturb the appointment of the election inspectors already made by the presiding officer of the municipal counting of Bauan. In thus so deciding, we were influenced by the question as to which of the two minority parties, namely, the Popular Front Party or the minority faction of the Nacionalista Party has a better right to the third inspector, and can exercise a better check and balance of the workings of the majority representation in the board of election inspectors. While we have

always adhered to the fundamental principle that no party shall be allowed to monopolized all election inspectors and poll clerks, yet we cannot close our eyes to the fact that the Nacionalista Party is only united and is under one leadership in so far as national politics and national policies are concerned, but divided on questions of local politics and local problems. Under the spirit of the law, a faction of the same party, or a political group if it consists and constitutes to be the real opposition in the locality and obtained the next immediate place therein during the election held in 1937, and presents candidate or candidates for the forthcoming election, is entitled to the third inspector. The necessary check and balance which is the object of the law in giving representation to, the different political parties in the election board is properly maintained and observed in this instance because although the two major political parties, the Partido Nacionalista Democratico, commonly known as the Anti Party and the Partido Nacionalista Pro Independencia, commonly known as the Pro Party, together with the many other local groups of the Nacionalista Party, the division of the Nacionalista Party, notwithstanding this fusion, into what is commonly known as the Pro and Anti factions in some province and in the other provinces under the name of local leader, is maintained. These factions of the Nacionalista Party have, since the election held in 1937 for provincial and municipal officials, continued to oppose each other in almost all municipalities of the country, vigorously and uncompromisingly, in the polls according to the records of this Commission, thus demonstrating that the Popular Front Party has not been the actual opposition party in some municipalities and therefore should not be entitled to recognition in the said municipalities under Section 70 of the Election Code where it did not obtain votes in the preceding election of 1937 to the prejudice of the majority faction of the Nacionalista Party which obtained the next largest number of votes in the 1937 regular election. The petitioner now presents this petition for review, praying that this court hold the aforecited decisions of November 12 and 29, 1940, to be erroneous and declare Pagkakaisa g Bayan to be the party entitled to nominate the third election inspector and his

substitute in Bauan, Batangas, as well as in other municipalities where conditions similar to those existing in the former obtain. As grounds for the allowance of this petition, the petitioner contends that the respondent Commission has erred: (a) in permitting the Nacionalista Party to have a monopoly of election inspectors in Bauan, Batangas, for the forthcoming elections; (b) in allowing the municipal mayor of Bauan, Batangas, to grant the third inspector to a faction, the so-called minority faction of the Nacionalista Party in said municipality, in controvention of the plain and unequivocal provisions of the Election Code; (c) in depriving Pagkakaisa g Bayan which the Commission itself recognizes to be the national political minority, of any representation in the board of inspectors in Bauan, Batangas, in the coming December 10th elections, contrary to the uniform doctrine laid down by this Hon. Supreme Court both before as well as after the enactment of the present Election Code; (d) in not holding that sec. 70 of the Election Code contemplates a situation where at least two national parties obtained votes in the preceding election, and is not applicable to the case of Bauan, Batangas, where the candidates in the 1937 elections all belonged to a single political party, the Nacionalista Party, although they belonged to different factions of that party; (e) in not holding that the votes received by the different factions of the Nacionalista Party in the 1937 elections in Bauan, Batangas, must be deemed to be votes received by the Nacionalista Party, and not as votes received by each of the contending faction of said party in that municipality; (f) in interpreting sec. 70 of the Election Code to mean that in all cases a political minority party must have participated and must have obtained the next largest number of votes in the next preceding election before it can claim the right to nominate the third minority inspector, and interpretation which would render empty and meaningless the provision of sec. 71 of the same Code which permits the granting of the third inspector to candidates of the opposition party even though it did not poll the next largest number of votes in the next preceding election, in cases where the

parties polling the largest and next largest number of votes at next preceding election have united; and (g) in not declaring Pagkakaisa g Bayan to be entitled to name the third election inspector in Bauan, Batangas, for the forthcoming elections, well as in all other municipalities where condition similar to, Bauan, Batangas, exist. The respondent Commission filed its answer on December 4, 1940, and among other things, alleges: 3. That the so-called majority and minority factions of the Nacionalista Party, in like situation, are not branches or faction that have seceded from the Nacionalista Party, but are branches and divisions of said Party duly recognized by the National Directorate thereof; 4. That said so-called majority and minority factions have presented different sets of candidates for provincial and/or municipal offices for the elections to be held on December 10, 1940; 5. That said majority and minority factions of the Nacionalista Party in Bauan. Batangas (as well as in the other municipalities mentioned in the petition) presented different sets of candidate and were the only parties whose candidates received votes in the next preceding election for provincial and municipal offices held in 1937; 6. That the Popular Front Party presented no candidates in any of the municipalities aforesaid at the said election of 1937, and consequently polled no votes therein; It is admitted that the minority group which was accorded the minority representation on the boards of election inspectors in Bauan, Batangas, is but a fraction of the Nationalista Party, which faction obtained the next largest number of votes at the immediately preceding election in the said municipality. It is likewise admitted that Pagkakaisa g Bayan is a party of national standing but did not take part in the immediately preceding election in the said municipality. The principal question to be determined, therefore, is as between a faction of party which obtained the next largest number of votes in the preceding election and national party which did not

participate in such election and did not obtain votes therein, which has a better right to minority representation on the boards of election inspectors. The question here presented is not specifically provided for the Election Code, and if we were to interpret section 70 of the said Code strictly, neither the faction nor the party in question would be entitled to name the third election inspection. We are of the opinion, however, that in case of doubt the balance should be inclined in favor of an interpretation which would effectively safeguard the purity of suffrage and avoid a monopoly of inspectors of election by single party. It is, of course, to be expected that the opposing group of the majority party will check up the actuations of the other group and guard against abuses during the entire period of election, but this, is only true in cases where the two groups of the majority party have different candidates for all the provincial and municipal offices. Upon the other hand, if Pagkakaisa g Bayan is not accorded an inspector of election, the result would be that a single party would have a monopoly of the election inspectors contrary to the spirit and purpose of the law. In the case of Emiliano Tria Tirona vs. The Municipal Council of Dagupan, Pangasinan, 36 O.G. 1102, we said: . . . It is clear, however, that the purpose of the legislature in providing for a system of political representation to which it is entitled should not be permitted. We are of the opinion and so hold that where the two major political parties at the last preceding general elections have fused or consolidated into one party, and there are two sets of candidates of this party for elective provincial and municipal candidates of this party is entitled to one inspector and substitute inspector and substitute inspector of election in each and every electoral precinct of the municipality. As it does not appear that the Partido Nacionalista has presented official candidates but that each of the two wings of this party has presented a complete ticket of candidates for provincial and municipal offices in Pangasinan, one of the two inspectors and substitute inspectors of election in every electoral precinct of the municipality of Dagupan shall correspond to the anti faction and the other inspector and substitute inspector to the pro

faction. The third inspector and substitute inspector shall go to the Frente Popular. The judgment of the lower court is accordingly reversed and the municipal council of Dagupan is hereby ordered to meet within 48 hours from notice of this decision and to revoke the appointments of inspectors and substitute inspectors of election for the anti faction and forthwith to appoint an inspector and substitute inspector of election for the Frente Popular in each and every electoral precinct of Dagupan, Pangasinan, such appointments for the Frente Popular to be made in accordance with the proposal of the duly authorized representative of this party in the province or municipality aforementioned. We see no reason why we should depart from the doctrine laid down in the above-entitled case. Each faction of the Nacionalista Party in Bauan, Batangas, is, therefore, entitled to one inspector and the Pagkakaisa g Bayan to the third inspector in each and every precinct of the municipality, such inspectors to be appointed in the manner prescribed by section 73 of Commonwealth Act No. 357. The decision of the Commission on Elections is hereby reversed and the presiding officer of the municipal council of Bauan, Batangas, is hereby ordered, through the Commission on Elections, to rescind his action granting the majority group two inspectors and to forthwith appoint an inspector of election for Pagkakaisa g Bayan in each and every electoral precinct of the municipality, such appointments to be made in accordance with the proposal of the national directorate of said party. Without any pronouncement regarding costs. So ordered.

Tolentino, Jr. headed the COMELEC Task Force to have administrative oversight of the elections in Sulu. On May 12, 1998, some election inspectors and watchers informed Atty. Tolentino, Jr. of discrepancies between the election returns and the votes cast for the mayoralty candidates in the municipality of Pata. To avoid a situation where proceeding with automation will result in an erroneous count, he suspended the automated counting of ballots in Pata and immediately communicated the problem to the technical experts of COMELEC and the suppliers of the automated machine. After the consultations, the experts told him that the problem was caused by misalignment of the ovals opposite the names of candidates in the local ballots. They found nothing wrong with the automated machines. The error was in the printing of the local ballots, as a consequence of which, the automated machines failed to read them correctly. Atty. Tolentino, Jr. called for an emergency meeting of the local candidates and the military-police officials overseeing the Sulu elections. Among those who attended were petitioner Tupay Loong and private respondent Abdusakar Tan and intervenor Yusop Jikiri (candidates for governor.) The meeting discussed how the ballots in Pata should be counted in light of the misaligned ovals. There was lack of agreement. Some recommended a shift to manual count (Tan et al) while the others insisted on automated counting (Loong AND Jikiri). Reports that the automated counting of ballots in other municipalities in Sulu was not working well were received by the COMELEC Task Force. Local ballots in five (5) municipalities were rejected by the automated machines. These municipalities were Talipao, Siasi, Tudanan, Tapul and Jolo. The ballots were rejected because they had the wrong sequence code. Before midnight of May 12, 1998, Atty. Tolentino, Jr.

LOONG V COMELEC FACTS: Automated elections systems was used for the May 11, 1998 regular elections held in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) which includes the Province of Sulu. Atty. Jose

was able to send to the COMELEC en banc his report and recommendation, urging the use of the manual count in the entire Province of Sulu. 6 On the same day, COMELEC issued Minute Resolution No. 981747 ordering a manual count but only in the municipality of Pata.. The next day, May 13, 1998,

COMELEC issued Resolution No. 98-1750 approving, Atty. Tolentino, Jr.s recommendation and the manner of its implementation. On May 15, 1998, the COMELEC en banc issued Minute Resolution No. 981796 laying down the rules for the manual count. Minute Resolution 98-1798 laid down the procedure for the counting of votes for Sulu at the PICC. COMELEC started the manual count on May 18, 1998. ISSUE: 1. Whether or not a petition for certiorari and prohibition under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court is the appropriate remedy to invalidate the disputed COMELEC resolutions. 2. Assuming the appropriateness of the remedy, whether or not COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction in ordering a manual count. (The main issue in the case at bar) 2.a. Is there a legal basis for the manual count? 2.b. Are its factual bases reasonable? 2.c. Were the petitioner and the intervenor denied due process by the COMELEC when it ordered a manual count? 3. Assuming the manual count is illegal and that its result is unreliable, whether or not it is proper to call for a special election for the position of governor of Sulu. HELD: The petition of Tupay Loong and the petition in intervention of Yusop Jikiri are dismissed, there being no showing that public respondent gravely abused its discretion in issuing Minute Resolution Nos. 98-1748, 98-1750, 98-1796 and 98-1798. Our status quo order of June 23, 1998 is lifted. (1.) Certiorari is the proper remedy of the petitioner. The issue is not only legal but one of first impression and undoubtedly suffered with significance to the entire nation. It is adjudicatory of the right of the petitioner, the private respondents and the intervenor to the position of governor of Sulu. These are enough considerations to call for an exercise of the certiorari jurisdiction of this Court. (2a). A resolution of the issue will involve an interpretation of R.A. No. 8436 on automated election in relation to the broad power of the COMELEC under Section 2(1), Article IX(C) of the Constitution to

enforce and administer all laws and regulations relative to the conduct of an election , plebiscite, initiative, referendum and recall. Undoubtedly, the text and intent of this provision is to give COMELEC all the necessary and incidental powers for it to achieve the objective of holding free, orderly, honest, peaceful, and credible elections. The order for a manual count cannot be characterized as arbitrary, capricious or whimsical. It is well established that the automated machines failed to read correctly the ballots in the municipality of Pata The technical experts of COMELEC and the supplier of the automated machines found nothing wrong the automated machines. They traced the problem to the printing of local ballots by the National Printing Office. It is plain that to continue with the automated count would result in a grossly erroneous count. An automated count of the local votes in Sulu would have resulted in a wrong count, a travesty of the sovereignty of the electorate In enacting R.A. No. 8436, Congress obviously failed to provide a remedy where the error in counting is not machine-related for human foresight is not all-seeing. We hold, however, that the vacuum in the law cannot prevent the COMELEC from levitating above the problem. . We cannot kick away the will of the people by giving a literal interpretation to R.A. 8436. R.A. 8436 did not prohibit manual counting when machine count does not work. Counting is part and parcel of the conduct of an election which is under the control and supervision of the COMELEC. It ought to be selfevident that the Constitution did not envision a COMELEC that cannot count the result of an election. It is also important to consider that the failures of automated counting created post election tension in Sulu, a province with a history of violent elections. COMELEC had to act desively in view of the fast deteriorating peace and order situation caused by the delay in the counting of votes (2c) Petitioner Loong and intervenor Jikiri were not denied process. The Tolentino memorandum clearly shows that they were given every opportunity to oppose the manual count of the local ballots in Sulu. They were orally heard. They later submitted written position papers. Their representatives escorted the

transfer of the ballots and the automated machines from Sulu to Manila. Their watchers observed the manual count from beginning to end. 3. The plea for this Court to call a special election for the governorship of Sulu is completely off-line. The plea can only be grounded on failure of election. Section 6 of the Omnibus Election Code tells us when there is a failure of election, viz: Sec. 6. Failure of election. If, on account of force majeure, terrorism, fraud, or other analogous causes, the election in any polling place has not been held on the date fixed, or had been suspended before the hour fixed by law for the closing of the voting, or after the voting and during the preparation and the transmission of the election returns or in the custody or canvass thereof, such election results in a failure to elect, and in any of such cases the failure or suspension of election would affect the result of the election, the Commission shall on the basis of a verified petition by any interested party and after due notice and hearing, call for the holding or continuation of the election, not held, suspended or which resulted in a failure to elect but not later than thirty days after the cessation of the cause of such postponement or suspension of the election or failure to elect. There is another reason why a special election cannot be ordered by this Court. To hold a special election only for the position of Governor will be discriminatory and will violate the right of private respondent to equal protection of the law. The records show that all elected officials in Sulu have been proclaimed and are now discharging their powers and duties. These officials were proclaimed on the basis of the same manually counted votes of Sulu. If manual counting is illegal, their assumption of office cannot also be countenanced. Private respondents election cannot be singled out as invalid for alikes cannot be treated unalikes. The plea for a special election must be addressed to the COMELEC and not to this Court.

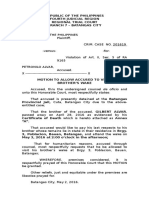

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. 142527 March 1, 2001

ARSENIO ALVAREZ, petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and LA RAINNE ABAD-SARMIENTO, respondents. RESOLUTION QUISUMBING, J.: This petition for certiorari assails the Resolution of the Commission on Elections En Banc, denying the Motion for Reconsideration of herein petitioner and affirming the Resolution of the Second Division of the COMELEC that modified the decision dated December 4, 1997 of the Metropolitan Trial Court, Br. 40, of Quezon City in Election Case No. 97-684. Said decision declared herein private respondent La Rainne Abad-Sarmiento the duly elected Punong Barangay of Barangay Doa Aurora, Quezon City during the May 12, 1997 elections; directed the herein petitioner to vacate and turnover the office of Punong Barangay to private respondent upon the finality of the resolution; and directed the Clerk of the COMELEC to notify the appropriate authorities of the resolution upon final disposition of this case, in consonance with the provisions of Section 260 of B.P. Blg. 881 otherwise known as the Omnibus Election Code, as amended.1 The facts of the case are as follows: On May 12, 1997, petitioner was proclaimed duly elected Punong Barangay of Doa Aurora, Quezon City. He received 590 votes while his opponent, private respondent Abad-Sarmiento, obtained 585 votes. Private respondent filed an election protest claiming irregularities, i.e. misreading and misappreciation of ballots by the Board of Election Inspectors. After petitioner answered and the issues were joined, the Metropolitan Trial Court ordered the reopening and recounting of the ballots in ten contested precincts. It subsequently rendered its decision that private respondent won the election. She garnered 596 votes while petitioner got 550 votes after the recount.2 On appeal, the Second Division of the COMELEC ruled that private respondent won over petitioner. Private respondent, meanwhile, filed a Motion for Execution pending appeal which petitioner opposed. Both petitioner's Motion for Reconsideration and private respondent's Motion for Execution pending appeal were submitted for resolution. The COMELEC En Banc denied the Motion for Reconsideration and

ALVAREZ V COMELEC

affirmed the decision of the Second Division. It granted the Motion for Execution pending appeal. Petitioner brought before the Court this petition for Certiorari alleging grave abuse of discretion on the part of the COMELEC when: (1) it did not preferentially dispose of the case; (2) it prematurely acted on the Motion for Execution pending appeal; and (3) it misinterpreted the Constitutional provision that "decisions, final orders, or rulings of the Commission on Election contests involving municipal and barangay officials shall be final, executory and not appealable". First, petitioner avers that the Commission violated its mandate on "preferential disposition of election contests" as mandated by Section 3, Article IX-C, 1987 Constitution as well as Section 257, Omnibus Election Code that the COMELEC shall decide all election cases brought before it within ninety days from the date of submission. He points out that the case was ordered submitted for resolution on November 15, 19994 but the COMELEC En Banc promulgated its resolution only on April 4, 2000,5 four months and four days after November 14, 1999. We are not unaware of the Constitutional provision cited by petitioner. We agree with him that election cases must be resolved justly, expeditiously and inexpensively. We are also not unaware of the requirement of Section 257 of the Omnibus Election Code that election cases brought before the Commission shall be decided within ninety days from the date of submission for decision.6 The records show that petitioner contested the results of ten (10) election precincts involving scrutiny of affirmation, reversal, validity, invalidity, legibility, misspelling, authenticity, and other irregularities in these ballots. The COMELEC has numerous cases before it where attention to minutiae is critical. Considering further the tribunal's manpower and logistic limitations, it is sensible to treat the procedural requirements on deadlines realistically. Overly strict adherence to deadlines might induce the Commission to resolve election contests hurriedly by reason of lack of material time. In our view this is not what the framers of the Code had intended since a very strict construction might allow procedural flaws to subvert the will of the electorate and would amount to disenfranchisement of voters in numerous cases. Petitioner avers the COMELEC abused its discretion when it failed to treat the case preferentially. Petitioner misreads the provision in Section 258 of the Omnibus Election Code. It will be noted that the "preferential 7 disposition" applies to cases before the courts and not

those before the COMELEC, as a faithful reading of the section will readily show. Further, we note that petitioner raises the alleged delay of the COMELEC for the first time. As private respondent pointed out, petitioner did not raise the issue before the COMELEC when the case was pending before it. In fact, private respondent points out that it was she who filed a Motion for Early Resolution of the case when it was before the COMELEC. The active participation of a party coupled with his failure to object to the jurisdiction of the court or quasi-judicial body where the action is pending, is tantamount to an invocation of that jurisdiction and a willingness to abide by the resolution of the case and will bar said party from later impugning the court or the body's jurisdiction.8 On the matter of the assailed resolution, therefore, we find no grave abuse of discretion on this score by the COMELEC. Second, petitioner alleges that the COMELEC En Banc granted the Motion for Execution pending appeal of private respondents on April 2, 2000 when the appeal was no longer pending. He claims that the motion had become obsolete and unenforceable and the appeal should have been allowed to take its normal course of "finality and execution" after the 30day period. Additionally, he avers it did not give one good reason to allow the execution pending appeal. We note that when the motion for execution pending appeal was filed, petitioner had a motion for reconsideration before the Second Division. This pending motion for reconsideration suspended the execution of the resolution of the Second Division. Appropriately then, the division must act on the motion for reconsideration. Thus, when the Second Division resolved both petitioner's motion for reconsideration and private respondent's motion for execution pending appeal, it did so in the exercise of its exclusive appellate jurisdiction. The requisites for the grant of execution pending appeal are: (a) there must be a motion by the prevailing party with notice to the adverse party; (b) there must be a good reason for the execution pending appeal; and (c) the good reason 9 must be stated in a special order. In our view, these three requisites were present. In its motion for execution, private respondent cites that their case had been pending for almost three years and the remaining portion of the contested term was just two more years. In a number of similar cases and for the same good reasons, we upheld the COMELEC's decision to grant execution pending appeal in the best interest of the electorate.10Correspondingly, we do not find that the COMELEC abused its discretion when it allowed the execution pending appeal. Third, petitioner contends that the COMELEC misinterpreted Section 2 (2), second paragraph, Article IX-C of the 1987 Constitution. He insists that factual findings of the COMELEC in election cases involving municipal and barangay officials may still be appealed.

He cites jurisprudence stating that such decisions, final orders or rulings do not preclude a recourse to this Court by way of a special civil action for 11 certiorari, when grave abuse of discretion has 12 marred such factual determination, and when there is arbitrariness in the factual findings.13 We agree with petitioner that election cases pertaining to barangay elections may be appealed by way of a special civil action for certiorari. But this recourse is available only when the COMELEC's factual determinations are marred by grave abuse of discretion. We find no such abuse in the instant case. From the pleadings and the records, we observed that the lower court and the COMELEC meticulously pored over the ballots reviewed. Because of its fact-finding facilities and its knowledge derived from actual experience, the COMELEC is in a peculiarly advantageous position to evaluate, appreciate and decide on factual questions before it. Here, we find no basis for the allegation that abuse of discretion or arbitrariness marred the factual findings of the COMELEC. As previously held, factual findings of the COMELEC based on its own assessments and duly supported by evidence, are conclusive on this Court, more so in the absence of a grave abuse of discretion, arbitrariness, fraud, or error of law in the questioned resolutions.14 Unless any of these causes are clearly substantiated, the Court will not interfere with the COMELEC's findings of fact. WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DISMISSED, and the En Banc Resolution of the Commission on Election is AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner. SO ORDERED.

You might also like

- Advice On The Action Taken1Document1 pageAdvice On The Action Taken1Nikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reduction Bail-CAPILLO 2Document2 pagesMotion For Reduction Bail-CAPILLO 2Nikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Envelope - Region Brown EnveloprDocument2 pagesEnvelope - Region Brown EnveloprNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Agreement Know All Men by These PresentsDocument4 pagesAgreement Know All Men by These PresentsNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Delayed Registration-Marriage ContractDocument2 pagesAffidavit Delayed Registration-Marriage ContractNikki Mendoza100% (1)

- Affidavit - 2 Disinterested - MALEDocument1 pageAffidavit - 2 Disinterested - MALENikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Demurrer To Evidence - Ronald Allan Melgar (As1)Document4 pagesDemurrer To Evidence - Ronald Allan Melgar (As1)Nikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of DesistanceDocument1 pageAffidavit of DesistanceNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Consent Travel Abroad ManiagoDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Consent Travel Abroad ManiagoNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Release Driver's LicenseDocument2 pagesMotion To Release Driver's LicenseNikki Mendoza0% (1)

- Affidavit - Solo ParentDocument2 pagesAffidavit - Solo ParentNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Enter Into Plea Bargaining Catilo & Tarcelo PaoDocument1 pageMotion To Enter Into Plea Bargaining Catilo & Tarcelo PaoNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Nso DALINGAYDocument3 pagesAffidavit Nso DALINGAYNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Action Taken BoolDocument2 pagesAction Taken BoolNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Petition 4 Correction-Gender, First Name-Amado B. ManaloDocument4 pagesPetition 4 Correction-Gender, First Name-Amado B. ManaloNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- A G R E E M E N T-Nenita Uy PerezDocument2 pagesA G R E E M E N T-Nenita Uy PerezNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Allow Accused To Attend Burial - Doc (Asi)Document2 pagesMotion To Allow Accused To Attend Burial - Doc (Asi)Nikki Mendoza100% (1)

- Comment-San Joses JapDocument3 pagesComment-San Joses JapNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- OppositionDocument3 pagesOppositionNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Release Cash Bond-Family CourtDocument2 pagesMotion To Release Cash Bond-Family CourtNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Reply Affidavit Adoyo9262 7610Document3 pagesReply Affidavit Adoyo9262 7610Nikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Lift Warrant-ConfinedDocument2 pagesMotion To Lift Warrant-ConfinedNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Petition For Bail - nonbailableOFFENSE-MANOLITO GONZALEZDocument2 pagesPetition For Bail - nonbailableOFFENSE-MANOLITO GONZALEZNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit - 2 Disinterested2Document1 pageAffidavit - 2 Disinterested2Nikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Lift Warrant-84-BurogDocument1 pageMotion To Lift Warrant-84-BurogNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Fourth Judicial Region Regional Trial Court Branch 8 - Batangas CityDocument4 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Fourth Judicial Region Regional Trial Court Branch 8 - Batangas CityNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Demurrer To Evidence - PaglicauanDocument17 pagesDemurrer To Evidence - PaglicauanNikki Mendoza75% (4)

- Affidavit of Discrepancy: Republic of The Philippines) City of Batangas) S.SDocument1 pageAffidavit of Discrepancy: Republic of The Philippines) City of Batangas) S.SNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Leave To File Demurrer - Reyes - 9165 (SW Possession)Document3 pagesMotion For Leave To File Demurrer - Reyes - 9165 (SW Possession)Nikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of 2 Disinterested PersonsDocument1 pageAffidavit of 2 Disinterested PersonsNikki MendozaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 25444sm SFM Finalnewvol2 Cp12 Chapter 12Document54 pages25444sm SFM Finalnewvol2 Cp12 Chapter 12Prin PrinksNo ratings yet

- Imran Khan: The Leader, The Champion and The Survivor: November 2022Document62 pagesImran Khan: The Leader, The Champion and The Survivor: November 2022Imran HaiderNo ratings yet

- Swiss Public Transportation & Travel SystemDocument42 pagesSwiss Public Transportation & Travel SystemM-S.659No ratings yet

- Account StatementDocument12 pagesAccount StatementNarendra PNo ratings yet

- Financial Policy For IvcsDocument11 pagesFinancial Policy For Ivcsherbert pariatNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Federal ExpressDocument3 pagesCase Study On Federal ExpressDipanjan RoychoudharyNo ratings yet

- Criteria O VS S F NI Remarks: St. Martha Elementary School Checklist For Classroom EvaluationDocument3 pagesCriteria O VS S F NI Remarks: St. Martha Elementary School Checklist For Classroom EvaluationSamantha ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- ALBAO - BSChE2A - MODULE 1 (RIZAL)Document11 pagesALBAO - BSChE2A - MODULE 1 (RIZAL)Shaun Patrick AlbaoNo ratings yet

- HSM340 Week 4 Homework 1 2 3Document3 pagesHSM340 Week 4 Homework 1 2 3RobynNo ratings yet

- Apostrophes QuizDocument5 pagesApostrophes QuizLee Ja NelNo ratings yet

- SodomiaDocument10 pagesSodomiaJason Camilo Hoyos ObandoNo ratings yet

- GeM Bidding 2062861Document6 pagesGeM Bidding 2062861ManishNo ratings yet

- Bilingual TRF 1771 PDFDocument18 pagesBilingual TRF 1771 PDFviviNo ratings yet

- Upstream Pre B1 Unit Test 9Document3 pagesUpstream Pre B1 Unit Test 9Biljana NestorovskaNo ratings yet

- The True Meaning of Lucifer - Destroying The Jewish MythsDocument18 pagesThe True Meaning of Lucifer - Destroying The Jewish MythshyperboreanpublishingNo ratings yet

- Program Evaluation RecommendationDocument3 pagesProgram Evaluation Recommendationkatia balbaNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Formal and Informal Sector Employment in The Urban Areas of Turkey (#276083) - 257277Document15 pagesDeterminants of Formal and Informal Sector Employment in The Urban Areas of Turkey (#276083) - 257277Irfan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Ellison C ct807 m8 MediaanalysisprojectDocument9 pagesEllison C ct807 m8 Mediaanalysisprojectapi-352916175No ratings yet

- Europeanization of GreeceDocument20 pagesEuropeanization of GreecePhanes DanoukopoulosNo ratings yet

- Glory To GodDocument2 pagesGlory To GodMonica BautistaNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental ProfessionalsDocument8 pagesEndodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental Professionalsbobs_fisioNo ratings yet

- Pietro Mascagni and His Operas (Review)Document7 pagesPietro Mascagni and His Operas (Review)Sonia DragosNo ratings yet

- LIBOR Transition Bootcamp 2021Document11 pagesLIBOR Transition Bootcamp 2021Eliza MartinNo ratings yet

- 4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisDocument13 pages4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisAnabel Marinda TulihNo ratings yet

- Internet Marketing Ch.3Document20 pagesInternet Marketing Ch.3Hafiz RashidNo ratings yet

- DR Sebit Mustafa, PHDDocument9 pagesDR Sebit Mustafa, PHDSebit MustafaNo ratings yet

- Glassix Walkthrough v0.15.1Document5 pagesGlassix Walkthrough v0.15.1JesusJorgeRosas50% (2)

- NEDA ReportDocument17 pagesNEDA ReportMartin LanuzaNo ratings yet

- Case Report UnpriDocument17 pagesCase Report UnpriChandra SusantoNo ratings yet

- Cadet Basic Training Guide (1998)Document25 pagesCadet Basic Training Guide (1998)CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet