Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alice in Trade-Land: The Politics of TTIP

Uploaded by

German Marshall Fund of the United StatesCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alice in Trade-Land: The Politics of TTIP

Uploaded by

German Marshall Fund of the United StatesCopyright:

Available Formats

Wider Atlantic Program

February 2014

Policy Brief

Alice in Trade-Land: The Politics of TTIP

by Jim Kolbe

Summary: Launched with great fanfare at the G20 summit last June, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) has alternately been proclaimed the historic joining of the worlds two largest economies and ridiculed as a desperate lifeline being thrown to the same two economies. By most economic measurements, TTIP should be seen as a clear winner on both sides of the Atlantic. And greater economic cooperation could forge stronger political links leading to greater political, diplomatic, and military cooperation between the United States and the EU. It might revive the moribund multi-lateral Doha trade negotiations. But the TTIP prize at the end of the rainbow is not so much about trade and economics as it is about the politics of the agreement. And the politics comes in many hues and shades, with endless riddles and diversionary paths.

Alice: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here? Cheshire Cat: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to. Alice: I dont much care where. Cat: Then it doesnt matter which way you go. Alice: so long as I get somewhere. Cat: Oh, you are sure to do that, if only you walk long enough Introduction Trade negotiations and the sherpas who conduct them sometimes resemble Alice in Wonderland never quite sure of where they are going, but certain if they walk long enough they will get there. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership now commonly known as TTIP may belong on these same pages. Launched with great fanfare at the G20 summit last June, TTIP has alternately been proclaimed the historic joining of the worlds two largest economies and ridiculed as a desperate lifeline being thrown to the same two economies, both drowning

in the rising waters of emerging markets, most notably China. By most economic measurements, TTIP should be seen as a clear winner on both sides of the Atlantic, a great opportunity to reinvigorate both economic platforms. The combined economies of the United States and the 28 countries of the European Union already account for 26 percent of the worlds exports of goods, 44 percent of services, and 39 percent of foreign direct investment (FDI). While existing tariffs on industrial goods are low on both sides (averaging 4 percent in Europe and even less in the United States), the complete elimination of tariffs, even if that is all TTIP ever concluded, would add over $32 billion to the EU economies and $13 billion to the U.S. economy on an annual basis. Given their size, that is not a great deal, but if you consider the possibility of adding the elimination of even 25 percent of non-tariff barriers on goods and services and half of the barriers on procurement, the numbers rise to $163 billion and $130 billion, respectively. Annually. But the economic boost measured in dollars or euros only tells a part of the story, actually a rather small part of it. A TTIP could eliminate the

1744 R Street NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 745 3950 F 1 202 265 1662 E info@gmfus.org

Wider Atlantic Program

Policy Brief

embarrassingly high import tariffs that still exist on certain products up to 205 percent on some agriculture items exported to Europe and as much as 42 percent on textiles trying to enter the United States. But it is in setting global standards that a TTIP promises the greatest rewards and faces the biggest challenges. The United States and EU together dominate the worlds financial markets. Achieving convergence or common regulatory standards could leave in its wake an explosion of growth in these markets. While this industry is complex and the regulatory regimes equally so, a TTIP might well provide a test bed for new crossAtlantic regulatory cooperation. There are other areas outside the economic sphere that would argue for pushing forward to successfully complete a TTIP negotiation. Greater economic cooperation could forge stronger political links leading to greater political, diplomatic, and military cooperation between the United States and the EU. It might revive the moribund multilateral Doha trade negotiations. It could spur new scientific advances through increased research and development links. TTIP is also likely to have positive implications for the wider Atlantic community. Just as it will draw the United States and Europe into closer economic and political cooperation, inevitably it will also exert a pull on countries along the Atlantic Rim particularly in the Caribbean, North Africa, and Brazil. They will find the benefits of closer economic cooperation with the expanded, integrated market of the United States and EU hard to ignore. Similarly, the TTIP axis will see increasing opportunities for trade and investment in the Atlantic Rim countries that enjoy growth rates exceeding those of TTIP. Given the obvious benefits from concluding a trade and investment agreement between the Atlantic partners, one might wonder why Alice would not ask Cheshire Cat straightaway for the most direct path to a successful conclusion of a TTIP agreement. The answer, of course, is that the TTIP prize at the end of the rainbow is not so much about trade and economics as it is about the politics of the agreement. And the politics comes in many hues and shades, with endless riddles and diversionary paths. Global Political Considerations Lest it appear that the politics of TTIP are opaque or impenetrable, it is best to start by accentuating the posi2

One might wonder why Alice would not ask Cheshire Cat straightaway for the most direct path to a successful conclusion of a TTIP agreement.

tive. After all, this is an agreement between two partners equal in size, with a wide set of shared values. Both share a common commitment to environmental and labor standards. A TTIP that is presented to Congress will not be burdened with the opposition of organized labor that has hamstrung other trade agreements. With TTIP, labor need not fear losing jobs to a low-wage country. Indeed, it could turn out that organized labor in the United States welcomes the agreement because it could enable them to argue for adoption of the higher wages and employment standards found in Europe. But the political hurdles to be overcome are also very high. First, there are the risks to be considered for the global trading system. The most common argument offered against bilateral or regional agreements such as TTIP is that they discriminate against countries not included. Such agreements create what Jagdish Bhagwati calls the spaghetti bowl of trade1 proliferating agreements that engender myriad different trading rules and tariff regimes. Instead of leading the world toward a common trading regime, such agreements actually move away from liberalized trade and result in contradictory sets of rules. Another argument made is that failure to succeed in the negotiations, once launched, could lead to a loss of credibility for both Europe and the United States, that they lack the capability of moving the world toward more liberalized trade. If the United States and Europe cant reach an agreement between themselves, according to this argument, can they ever credibly argue on any other world stage for more trade liberalization or cooperation? Then there is the simple but practical argument that neither side has the capacity to undertake such a complex negotia1 Jagdish Bhagwati, U.S. Trade Policy: The Infatuation with Free Trade Agreements, in Bhagwati and Kruger, The Dangerous Drift to Preferential Trade Agreements (Washington, DC, AEI Press, 1995).

Wider Atlantic Program

Policy Brief

tion especially not when the United States is at the same time in the middle of negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership with a dozen Asia and Pacific Rim countries, and Europe is putting the finishing touches on a trade agreement with Canada and beginning another with Japan. Still another argument is that it will weaken the WTO machinery for settling disputes arguably, the most successful part of the WTO. While it is true that an ideal world would have one multilateral agreement built on top of the last, and one common set of rules for settling disputes, the reality is that the last effort to make this happen the Doha Round has been mired in a negotiating swamp for more than a decade and has little or no hope of being revived on the scale of the grand and global trade agreement imagined more than a decade ago. Would not a regional agreement like TTIP especially one so large and embracing such a large part of the world economy be a step forward for the world trading system? Is it not better to embrace TTIP than leave a failed Doha round as the gravestone for liberalized trade? Meanwhile, the successful, if limited, conclusion to the last Doha ministerial meeting in Bali fills in some of the procedural pot holes that confront global trade on a daily basis. It is too early to say definitively, but it is possible this modest success could spur TTIP negotiators to solve some of the much larger and substantive potholes and speed bumps that confront their own trade negotiators. Moreover, the negative arguments can be mitigated by a TTIP that is open ended, one that includes a simple and easy accession process. Let the United States and EU negotiate their agreement, but then invite other countries to join TTIP. There should be simple steps for other countries that wish to sign up to the terms and conditions of the agreement without being allowed to dilute it. The foregoing are all external arguments or challenges for TTIP. They are not conditions of the agreement itself. A more serious set of political challenges are to be found within the framework of the agreement itself differences of varying magnitude over specific issues, but with the potential of derailing any agreement. Politics of the Agreement Two agricultural issues are particularly thorny. One is the broader topic of tariff levels and quotas, some narrowly applied, some more broadly. While Europe is not a major sugar-producing area, the United States continues to keep the domestic price of sugar arbitrarily high by setting a price floor and then buying sugar when the domestic price falls below that floor. For producing countries, imports are arbitrarily limited through a quota system. The result is a domestic price of sugar 80 percent above the world market price, driving candy manufacturers offshore and driving up prices for consumers on everything from cupcakes to breakfast cereal. More troublesome for TTIP are high U.S. tariffs on such items as textiles and footwear, thinly veiled protectionist measures targeted against European producers. Europes behavior is worse when it comes to agriculture. Lacking economies of scale in a densely populated continent, Europe imposes higher tariffs on a wide range of commodities and specialty crops. In other cases, phytosanitary rules or rules of origin are used to protect European markets from competition. But it is the issue of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) that sets many Europeans on edge and poses one of the most serious obstacles to successfully concluding TTIP. The United States considers the issue of GMOs which it pioneered and which fueled a green revolution a half century ago, turning famine into food abundance to be a matter settled by science and usage. Europeans continue to have much greater suspicion about GMOproduced food; Austria goes so far as to ban cultivation of any plants grown from GMO seeds. The issue extends beyond plants to animal products; Europe bans beef fed with hormones. Senator Max Baucus, from the beefproducing state of Montana and the current chair of the Senate Finance Committee, which has to approve any trade

3

Would not a regional agreement like TTIP especially one so large and embracing such a large part of the world economy be a step forward for the world trading system?

Wider Atlantic Program

Policy Brief

agreement, has said there will be no agreement without European concessions on this issue. The United States insists that the decision to allow the use of hormones or genetically modified seeds must be based on scientific evidence. Such a rule would clearly favor the U.S. position since nearly all European scientists agree that the evidence favors acceptance and use of GMO food stocks. But the issue continues to be a cultural and emotional one that transcends the logic of science. Threading their way through this issue will test the mettle of TTIP negotiators on both sides. Another issue on the European side is the so-called cultural exception the carve-out of entertainment, music, movies, and TV shows to maintain a separate cultural identity. For the United States, the entertainment industry represents one of its largest exports and its negotiating team will resist any efforts to keep substantive barriers in place. When the decision to launch the talks was announced in February, it was agreed that all trade matters would be on the table for discussion with no exceptions. However, the French were adamant in their insistence for a cultural carve-out, and it is a sign post of the difficult negotiations that lie ahead that the exception was included when the talks were launched four months later. On the U.S. side, one of the tough issues to resolve centers on government procurement. The WTO rules are clear that there has to be national treatment for procurement, that all companies seeking to do business through the bid process must be treated equally, regardless of national origin. However, the United States with its federal system has not only a federal procurement system but also procurement codes for 50 different states, and even includes variations in many municipalities. Many such procurement codes include a Buy America provision, or even a requirement to buy more locally. Such codes clearly flaunt the WTO directives on this matter, and some way must be found to satisfy all parties in a TTIP negotiation. It is on the ground of financial services that some of the most difficult negotiating terrain will be encountered. In the wake of the 2008 financial meltdown, the United States adopted the so-called Dodd-Frank Act to bring some order to the regulation of financial derivatives, investments, and capital requirements, and to assure greater consumer protection. Europeans have had to struggle with the architecture imposed by the Maastricht Treaty: a European

4

central bank alongside 28 separate national central banks, a handful of countries joining the common Euro currency, but with each country making its own fiscal policy on spending, debt, and deficit levels. The central issue is whether the TTIP negotiations can provide a framework for financial service regulation that reflects the lessons learned from the financial crisis on both sides of the Atlantic. A common regulatory scheme looks very attractive to the Europeans and they would like to see it incorporated into the trade negotiation. But the U.S. Treasury, led by Secretary Jack Lew, continues to pour cold water on this idea. In a meeting with the EU internal markets commissioner, Secretary Lew emphasized that prudential and financial regulatory cooperation should continue in existing and appropriate global fora, such as the G20, Financial Stability Board, and international standard setting bodies. In other words, leave financial services and any common regulatory schemes out of the TTIP negotiation. Expect Alice to have to travel a long path on this one.

The central issue is whether the TTIP negotiations can provide a framework for financial service regulation that reflects the lessons learned from the financial crisis on both sides of the Atlantic.

Without doubt, the largest benefit of a TTIP would be to converge or harmonize the regulations outside of financial services, regulations that fill up books on both sides and are maddeningly, but often inconsequentially, different. For example, they add about $3,000 to the cost of every European car imported into the United States, and about the same in the other direction, to gain compliance with the relevant safety and environmental standards. But is there anyone who doubts that European environmental standards are sufficient for a car driven in the United States, or that U.S. safety standards for automobiles leave drivers and passengers less protected than in Europe? Why not just

Wider Atlantic Program

Policy Brief

agree to accept each others rules where there are generally accepted standards? If this concept could be incorporated into TTIP for a broad swath of the economy, ranging from automobiles and aircraft to small appliances and medical devices to energy production, the effect on competitiveness for both Europe and the United States would be huge. Finally, there are a whole set of political bumps and potholes in the TTIP path that can best be categorized as political process. Some are long standing, while others emerge as the negotiations develop. In the latter basket is the recent kerfuffle over NSA eavesdropping. Some voices in Europe have suggested TTIP negotiations be suspended until adequate assurances are in place to prevent further eavesdropping. However, most public statements by leaders have been reassuring in their commitment to moving forward with TTIP negotiations. Similarly, the dust up over the budget and consequent three-week-long shut down of the government in Washington led to the cancellation of the second round of negotiations and raised some questions about the reliability of the United States as a negotiating partner. But those concerns seem relatively minor. Then there is the political timetable for both sides. The original goal was to complete negotiations before the EUs Commission expires at the end of 2014. However, such a short negotiating span seems very unrealistic. More realistic would be to complete the deal within the following two years, before U.S. President Barack Obama leaves office. Meanwhile, the politics of the European Parliament must be taken into account as they now must approve any agreement, just as the U.S. Congress must give its approval. The Question of Trade Promotion Authority But the big and largely unspoken unknown for TTIP is President Obamas authority to sign the agreement when his negotiators think they have the deal ready to finalize. To avoid the prospects of an agreement being picked apart in committee or in House and Senate debate, Congress uses a procedure called Trade Promotion Authority (TPA, formerly known as fast track). Boiled down to its essence, it gives the president the authority to negotiate trade agreements and submit them to Congress with the assurance that there will be a vote within a set amount of time and without amendments, or changes, being offered. In other words, a simple yes or no vote is required.

5

But the big and largely unspoken unknown for TTIP is President Obamas authority to sign the agreement when his negotiators think they have the deal ready to finalize.

Usually, such authority is granted at the beginning of negotiations. The authority of the TPA helps assure negotiators on all sides that when the best offer is put on the table and accepted, that agreement will not be carved up beyond recognition in the legislative process. Such presidential authority has not been extended since 2002 when it was granted to President George W. Bush to negotiate trade agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea. Republicans in both the House and Senate are wary of extending TPA to the president after what occurred in 2008 when President Bush used existing trade authority to submit the Colombia, Panama, and South Korean agreements to Congress, only to have the laws intent brushed aside by Speaker Pelosis decision to use the power of House rules to trump the requirement in the law for a vote. They want assurances there will be a vote if the agreements are completed and signed. It is the intersection of TTIP and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations that creates difficulties for Trade Promotion Authority. The objective of TPA is to insulate Congress from the tough decisions on specific trade provisions and make them consider the proposal in its entirety. But with TPP reaching the final stages of negotiation, it is the tough and controversial issues such as the wide gap between the United States and many of the less developed countries on wages and labor and environmental standards that are unresolved in that negotiation. The nearer TPP gets to the finish line, the more its controversial issues threaten to become a deal-breaker for TPA. Staffs on both sides of the Capitol have been working in a bipartisan way to find common ground for the presidents negotiating authority, but the discussions have not included substantive engagement with the White House or the U.S. Trade Representa-

Wider Atlantic Program

Policy Brief

tive. Consequently, presidential authority to complete TTIP could be imperiled by the trade negotiations taking place on the opposite side of the globe. The underlying question for our European TTIP partner could be how far they are willing to proceed down the negotiating path without certainty of having the TPA process in place when it would be needed to complete the negotiation and activate Congressional approval. While the bumps along the TTIP road are not insignificant, the reward at the end makes it worth the effort. Alice needs to be very clear about where she is trying to go; then perhaps Cheshire Cat can tell her how long it will take to get there and which is the easiest path to follow.

About the Author

Jim Kolbe currently serves as a senior transatlantic fellow for the German Marshall Fund of the United States. He served in the United States House of Representatives, elected for eleven consecutive terms, from 1985 to 2007, representing the Eighth (previously designated the Fifth) congressional district, in southeastern Arizona.

About GMF

The German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) strengthens transatlantic cooperation on regional, national, and global challenges and opportunities in the spirit of the Marshall Plan. GMF does this by supporting individuals and institutions working in the transatlantic sphere, by convening leaders and members of the policy and business communities, by contributing research and analysis on transatlantic topics, and by providing exchange opportunities to foster renewed commitment to the transatlantic relationship. In addition, GMF supports a number of initiatives to strengthen democracies. Founded in 1972 as a non-partisan, non-profit organization through a gift from Germany as a permanent memorial to Marshall Plan assistance, GMF maintains a strong presence on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition to its headquarters in Washington, DC, GMF has offices in Berlin, Paris, Brussels, Belgrade, Ankara, Bucharest, Warsaw, and Tunis. GMF also has smaller representations in Bratislava, Turin, and Stockholm.

About the OCP Policy Center

The OCP Policy Centers overarching objective is to enhance corporate and national capacities for objective policy analysis to foster economic and social development, particularly in Morocco and emerging economies through independent policy research and knowledge. It is creating an environment of informed and fact-based public policy debate, especially on agriculture, environment, and food security; macroeconomic policy, economic and social development, and regional economics; commodity economics; and understanding key regional and global evolutions shaping the future of Morocco. The Policy Center also emphasizes developing a new generation of leaders in the public, corporate, and civil society sector in Morocco; and more broadly in Africa.

About the Wider Atlantic Program

GMFs Wider Atlantic program is a research and convening partnership of GMF and Moroccos OCP Policy Center. The program explores the north-south and south-south dimensions of transatlantic relations, including the role of Africa and Latin America, and issues affecting the Atlantic Basin as a whole.

You might also like

- Cooperation in The Midst of Crisis: Trilateral Approaches To Shared International ChallengesDocument34 pagesCooperation in The Midst of Crisis: Trilateral Approaches To Shared International ChallengesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey's Travails, Transatlantic Consequences: Reflections On A Recent VisitDocument6 pagesTurkey's Travails, Transatlantic Consequences: Reflections On A Recent VisitGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The Iranian Moment and TurkeyDocument4 pagesThe Iranian Moment and TurkeyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Propaganda: The Roots and Instruments of Russia's Disinformation CampaignDocument19 pagesIsolation and Propaganda: The Roots and Instruments of Russia's Disinformation CampaignGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Small Opportunity Cities: Transforming Small Post-Industrial Cities Into Resilient CommunitiesDocument28 pagesSmall Opportunity Cities: Transforming Small Post-Industrial Cities Into Resilient CommunitiesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Why Russia's Economic Leverage Is DecliningDocument18 pagesWhy Russia's Economic Leverage Is DecliningGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The Awakening of Societies in Turkey and Ukraine: How Germany and Poland Can Shape European ResponsesDocument45 pagesThe Awakening of Societies in Turkey and Ukraine: How Germany and Poland Can Shape European ResponsesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- For A "New Realism" in European Defense: The Five Key Challenges An EU Defense Strategy Should AddressDocument9 pagesFor A "New Realism" in European Defense: The Five Key Challenges An EU Defense Strategy Should AddressGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey: Divided We StandDocument4 pagesTurkey: Divided We StandGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Defending A Fraying Order: The Imperative of Closer U.S.-Europe-Japan CooperationDocument39 pagesDefending A Fraying Order: The Imperative of Closer U.S.-Europe-Japan CooperationGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The West's Response To The Ukraine Conflict: A Transatlantic Success StoryDocument23 pagesThe West's Response To The Ukraine Conflict: A Transatlantic Success StoryGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The United States in German Foreign PolicyDocument8 pagesThe United States in German Foreign PolicyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Solidarity Under Stress in The Transatlantic RealmDocument32 pagesSolidarity Under Stress in The Transatlantic RealmGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- China's Risk Map in The South AtlanticDocument17 pagesChina's Risk Map in The South AtlanticGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Between A Hard Place and The United States: Turkey's Syria Policy Ahead of The Geneva TalksDocument4 pagesBetween A Hard Place and The United States: Turkey's Syria Policy Ahead of The Geneva TalksGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Common Ground For European Defense: National Defense and Security Strategies Offer Building Blocks For A European Defense StrategyDocument6 pagesCommon Ground For European Defense: National Defense and Security Strategies Offer Building Blocks For A European Defense StrategyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey Needs To Shift Its Policy Toward Syria's Kurds - and The United States Should HelpDocument5 pagesTurkey Needs To Shift Its Policy Toward Syria's Kurds - and The United States Should HelpGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Russia's Military: On The Rise?Document31 pagesRussia's Military: On The Rise?German Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- Pride and Pragmatism: Turkish-Russian Relations After The Su-24M IncidentDocument4 pagesPride and Pragmatism: Turkish-Russian Relations After The Su-24M IncidentGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- AKParty Response To Criticism: Reaction or Over-Reaction?Document4 pagesAKParty Response To Criticism: Reaction or Over-Reaction?German Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Brazil and Africa: Historic Relations and Future OpportunitiesDocument9 pagesBrazil and Africa: Historic Relations and Future OpportunitiesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Leveraging Europe's International Economic PowerDocument8 pagesLeveraging Europe's International Economic PowerGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The EU-Turkey Action Plan Is Imperfect, But Also Pragmatic, and Maybe Even StrategicDocument4 pagesThe EU-Turkey Action Plan Is Imperfect, But Also Pragmatic, and Maybe Even StrategicGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- After The Terror Attacks of 2015: A French Activist Foreign Policy Here To Stay?Document23 pagesAfter The Terror Attacks of 2015: A French Activist Foreign Policy Here To Stay?German Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- How Economic Dependence Could Undermine Europe's Foreign Policy CoherenceDocument10 pagesHow Economic Dependence Could Undermine Europe's Foreign Policy CoherenceGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey and Russia's Proxy War and The KurdsDocument4 pagesTurkey and Russia's Proxy War and The KurdsGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Whither The Turkish Trading State? A Question of State CapacityDocument4 pagesWhither The Turkish Trading State? A Question of State CapacityGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Russia's Long War On UkraineDocument22 pagesRussia's Long War On UkraineGerman Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- USA V BRACKLEY Jan6th Criminal ComplaintDocument11 pagesUSA V BRACKLEY Jan6th Criminal ComplaintFile 411No ratings yet

- Operation Manual: Auto Lensmeter Plm-8000Document39 pagesOperation Manual: Auto Lensmeter Plm-8000Wilson CepedaNo ratings yet

- (Bio) Chemistry of Bacterial Leaching-Direct vs. Indirect BioleachingDocument17 pages(Bio) Chemistry of Bacterial Leaching-Direct vs. Indirect BioleachingKatherine Natalia Pino Arredondo100% (1)

- 'K Is Mentally Ill' The Anatomy of A Factual AccountDocument32 pages'K Is Mentally Ill' The Anatomy of A Factual AccountDiego TorresNo ratings yet

- Tender Notice and Invitation To TenderDocument1 pageTender Notice and Invitation To TenderWina George MuyundaNo ratings yet

- Ramdump Memshare GPS 2019-04-01 09-39-17 PropsDocument11 pagesRamdump Memshare GPS 2019-04-01 09-39-17 PropsArdillaNo ratings yet

- Micropolar Fluid Flow Near The Stagnation On A Vertical Plate With Prescribed Wall Heat Flux in Presence of Magnetic FieldDocument8 pagesMicropolar Fluid Flow Near The Stagnation On A Vertical Plate With Prescribed Wall Heat Flux in Presence of Magnetic FieldIJBSS,ISSN:2319-2968No ratings yet

- Tygon S3 E-3603: The Only Choice For Phthalate-Free Flexible TubingDocument4 pagesTygon S3 E-3603: The Only Choice For Phthalate-Free Flexible TubingAluizioNo ratings yet

- sl2018 667 PDFDocument8 pagessl2018 667 PDFGaurav MaithilNo ratings yet

- Jazan Refinery and Terminal ProjectDocument3 pagesJazan Refinery and Terminal ProjectkhsaeedNo ratings yet

- Active and Passive Voice of Future Continuous Tense - Passive Voice Tips-1Document5 pagesActive and Passive Voice of Future Continuous Tense - Passive Voice Tips-1Kamal deep singh SinghNo ratings yet

- Application D2 WS2023Document11 pagesApplication D2 WS2023María Camila AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Put The Items From Exercise 1 in The Correct ColumnDocument8 pagesPut The Items From Exercise 1 in The Correct ColumnDylan Alejandro Guzman Gomez100% (1)

- 13 Fashion Studies Textbook XIDocument158 pages13 Fashion Studies Textbook XIMeeta GawriNo ratings yet

- Scharlau Chemie: Material Safety Data Sheet - MsdsDocument4 pagesScharlau Chemie: Material Safety Data Sheet - MsdsTapioriusNo ratings yet

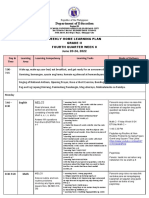

- Department of Education: Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade Ii Fourth Quarter Week 8Document8 pagesDepartment of Education: Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade Ii Fourth Quarter Week 8Evelyn DEL ROSARIONo ratings yet

- Product CycleDocument2 pagesProduct CycleoldinaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Quality Gurus Deming, Juran, Crosby, Imai, Feigenbaum & Their ContributionsDocument11 pagesOverview of Quality Gurus Deming, Juran, Crosby, Imai, Feigenbaum & Their ContributionsVenkatesh RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- IP68 Rating ExplainedDocument12 pagesIP68 Rating ExplainedAdhi ErlanggaNo ratings yet

- Vehicle Registration Renewal Form DetailsDocument1 pageVehicle Registration Renewal Form Detailsabe lincolnNo ratings yet

- Afu 08504 - International Capital Bdgeting - Tutorial QuestionsDocument4 pagesAfu 08504 - International Capital Bdgeting - Tutorial QuestionsHashim SaidNo ratings yet

- New Brunswick CDS - 2020-2021Document31 pagesNew Brunswick CDS - 2020-2021sonukakandhe007No ratings yet

- NGPDU For BS SelectDocument14 pagesNGPDU For BS SelectMario RamosNo ratings yet

- SQL Server 2008 Failover ClusteringDocument176 pagesSQL Server 2008 Failover ClusteringbiplobusaNo ratings yet

- Testbanks ch24Document12 pagesTestbanks ch24Hassan ArafatNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument4 pagesDaftar PustakaRamli UsmanNo ratings yet

- Basf Masterseal 725hc TdsDocument2 pagesBasf Masterseal 725hc TdsshashiNo ratings yet

- Trading Course DetailsDocument9 pagesTrading Course DetailsAnonymous O6q0dCOW6No ratings yet

- Modul-Document Control Training - Agus F - 12 Juli 2023 Rev1Document34 pagesModul-Document Control Training - Agus F - 12 Juli 2023 Rev1vanesaNo ratings yet

- Impolitic Art Sparks Debate Over Societal ValuesDocument10 pagesImpolitic Art Sparks Debate Over Societal ValuesCarine KmrNo ratings yet