Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Essentials of Contracts

Uploaded by

Francis Njihia KaburuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Essentials of Contracts

Uploaded by

Francis Njihia KaburuCopyright:

Available Formats

4) i) ii) iii)

Contracts II Consideration. Intention to create legal relations, Form, legality, vitiating factors

b) CONSIDERATION The mere fact of agreement alone does not make a contract. Both parties to the contract must provide consideration if they wish to sue on the contract. This means that each side must promise to give or do something for the other. ( ote! if a contract is made "y deed, then consideration is not needed.) For e#ample, if one party, $ (the promisor) promises to mow the lawn of another, B (the promisee), $%s promise will only "e enforcea"le "y B as a contract if B has provided consideration. The consideration from B might normally take the form of a payment of money "ut could consist of some other service to which $ might agree. Further, the promise of a money payment or service in the future is &ust as sufficient a consideration as payment itself or the actual rendering of the service. Thus the promisee has to give something in return for the promise of the promisor in order to convert a "are promise made in his favor into a "inding contract. Definition 'ush (. in Currie v Misa (1875) LR 10 Exch 153 define it thus) "... some right, i terest, !ro"it or #e e"it accrui g to o e !art$, or some "or#eara ce, %etrime t, &oss or res!o si#i&it$ give , su""ere% or u %erta'e #$ the other." The definition given "y *ir Frederick +ollock, approved "y 'ord ,unedin i (u &o! v )e&"ri%ge Lt% *1+15, -C 8.7, is as follows! "- act or "ore#eara ce o" o e !art$, or the !romise thereo", is the !rice "or /hich the !romise o" the other is #ought, a % the !romise thus give "or va&ue is e "orcea#&e." -ther definitions include) . *omething which is actually given or received in return for a promise (unknown source) . Benefit or detriment 0)ome %etrime t to the !&ai ti"" or some #e e"it to the %e"e %a t / Thomas v Thomas 0123 Its eventually defined as a "enefit gained or a detriment suffered. TYPES OF CONSIDERATION 1. Executor consi!eration Consideration is called 4e#ecutory4 where there is an e#change of promises to perform acts in the future, eg a "ilateral contract for the supply of goods where"y $ promises to deliver goods to B at a future date and B promises to pay on delivery. If $ does not deliver them, this is a "reach of contract and B can sue. If $ delivers the goods his consideration then "ecomes e#ecuted.

". Execute! consi!eration If one party makes a promise in e#change for an act "y the other party, when that act is completed, it is e#ecuted consideration, eg in a unilateral contract where $ offers 567 reward for the return of her lost hand"ag, if B finds the "ag and returns it, B%s consideration is e#ecuted. R#$ES %O&ERNIN% CONSIDERATION 1. Consi!eration 'ust not be (ast If one party voluntarily performs an act, and the other party then makes a promise, the consideration for the promise is said to "e in the past. The rule is that past consideration is no consideration, so it is not valid and cannot "e used to sue on a contract. For e#ample, $ gives B a lift home in his car. -n arrival B promises to give $ 56 towards the petrol. $ cannot enforce this promise as his consideration, giving B a lift, is past. *ee! Re Mc -r%&e (1+51) $ wife and her three grown.up children lived together in a house. The wife of one of the children did some decorating and later the children promised to pay her 8211 and they signed a document to this effect. It was held that the promise was unenforcea"le as all the work had "een done "efore the promise was made and was therefore past consideration. Exce(tions to t)is ru*e+ (a) Previous request If the promisor has previously asked the other party to provide goods or services, then a promise made after they are provided will "e treated as "inding. *ee! Lam!&eigh v 1raith/ait (1215) Braithwait killed someone and then asked 'ampleigh to get him a pardon. 'ampleigh got the pardon and gave it to Braithwait who promised to pay 'ampleigh 8077 for his trou"le. It was held that although 'ampleigh%s consideration was past (he had got the pardon) Braithwaite%s promise to pay could "e linked to Braithwaite%s earlier re9uest and treated as one agreement, so it could "e implied at the time of the re9uest that 'ampleigh would "e paid. (b) Business situations If something is done in a "usiness conte#t and it is clearly understood "y "oth sides that it will "e paid for, then past consideration will "e valid. *ee! Re Case$3s 4ate t (18+5) $ and B owned a patent and C was the manager who had worked on it for two years. $ and B then promised C a one.third share in the invention for his help in developing it. The patents were transferred to C "ut $ and B then claimed their return. It was held that C could rely on the agreement. :ven though C%s consideration was in the past, it had "een done in a "usiness situation, at the re9uest of $ and B and it was understood "y "oth sides that C would "e paid and the su"se9uent promise to pay merely fi#ed the amount. (c) The Bills of Exchange Act ;nder s3<(0) it is provided that any antecedent de"t or lia"ility including past services is valid consideration for a "ill of e#change. For e#ample, $ mows B%s lawn and a week later B gives $ a che9ue for 507. $%s work is valid consideration in e#change for the che9ue. :.g. If the "rothers. in.law in Re ,cAr!*e, a"ove had given =rs. =c$rdle a "ill of e#change or promissory note for 3

5211 paya"le after their mother%s death they would have "een lia"le on it even though the work on the house had "een completed "y the time of drawing the "ill or promissory note. ". Consi!eration 'ust be sufficient but nee! not be a!e-uate +roviding consideration has some value, the courts will not investigate its ade9uacy. Sufficient >here consideration is recogni?ed "y the law as having some value, it is descri"ed as 4real4 or 4sufficient4 consideration. 6homas v 6homas $ payment of rent of one pound was taken to "e sufficient. Adequate The consideration paid need not "e e9ual the value of the other thing . law is not concerned with whether a party has made a good "argain or a "ad one @ provided it is freely entered into. Cha!!&e v 7est&e (1+5+) estle were running a special offer where"y mem"ers of the pu"lic could o"tain a music record "y sending off three wrappers from estle%s chocolate "ars plus some money. The copyright to the records was owned "y Chapple, who claimed that there had "een "reaches of their copyright. The case turned round whether the three wrappers were part of the consideration. It was held that they were, even though they were then thrown away when received. .. Consi!eration 'ust 'o/e fro' t)e (ro'isee The person who wishes to enforce the contract must show that they provided consideration) it is not enough to show that someone else provided consideration. The promisee must show that consideration 4moved from4 (ie, was provided "y) him. The consideration does not have to move to the promisor. If there are three parties involved, pro"lems may arise. *ee! 4rice v Easto (1833) :aston made a contract with A that in return for A doing work for him, :aston would pay +rice 8 0B. A did the work "ut :aston did not pay, so +rice sued. It was held that +rice%s claim must fail, as he had not provided consideration. 4. Forbearance to sue If one person has a valid claim against another (in contract or tort) "ut promises to for"ear from enforcing it, that will constitute valid consideration if made in return for a promise "y the other to settle the claim. *ee! -&&ia ce 1a ' v 1room (182.) The defendant owed an unsecured de"t to the plaintiffs. >hen the plaintiffs asked for some security, the defendant promised to provide some goods "ut never produced them. >hen the plaintiffs tried to enforce the agreement for the security, the defendant argued that the plaintiffs had not provided any consideration. It was held that normally in such a case, the "ank would promise not to enforce the de"t, "ut this was not done here. By not suing, however, the "ank had shown for"earance and this was valid consideration, so the agreement to provide security was "inding.

0. Existin1 (ub*ic !ut If someone is under a pu"lic duty to do a particular task, then agreeing to do that task is not sufficient consideration for a contract. *ee! Co&&i s v 8o%e"ro$ (1831) Dodefroy promised to pay Collins if Collins would attend court and give evidence for Dodefroy. Collins had "een served with a su"poena (ie, a court order telling someone they must attend). Collins sued for payment. It was held that as Collins was under a legal duty to attend court he had not provided consideration. Eis action therefore failed. If someone e#ceeds their pu"lic duty, then this may "e valid consideration. *ee! 8&ass#roo'e 1ros v 8&amorga Cou t$ Cou ci& *1+55, -C 570. The police were under a duty to protect a coal mine during a strike, and proposed mo"ile units. The mine owner promised to pay for police to "e stationed on the premises. The police complied with this re9uest "ut when they claimed the money, the mine owner refused to pay saying that the police had simply carried out their pu"lic duty. It was held that although the police were "ound to provide protection, they had a discretion as to the form it should take. $s they "elieved mo"ile police were sufficient, they had acted over their normal duties. The e#tra protection was good consideration for the promise "y the mine owner to pay for it and so the police were entitled to payment. 2. Existin1 contractua* !ut If someone promises to do something they are already "ound to do under a contract, that is not valid consideration. )ti&' v M$ric' (180+) Two out of eleven sailors deserted a ship. The captain promised to pay the remaining crew e#tra money if they sailed the ship "ack, "ut later refused to pay. It was held that as the sailors were already "ound "y their contract to sail "ack and to meet such emergencies of the voyage, promising to sail "ack was not valid consideration. Thus the captain did not have to pay the e#tra money. Exceptions i) Conduct "eyond e#isting contractual duties. If one e#ceeds the pu"lic duty, then it shall "e good consideration. see 9art&e$ v 4o so #$ (1857) >hen nineteen out of thirty.si# crew of a ship deserted, the captain promised to pay the remaining crew e#tra money to sail "ack, "ut later refused to pay saying that they were only doing their normal &o"s. In this case, however, the ship was so seriously undermanned that the rest of the &ourney had "ecome e#tremely ha?ardous. It was held that sailing the ship "ack in such dangerous conditions was over and a"ove their normal duties. It discharged the sailors from their e#isting contract and left them free to enter into a new contract for the rest of the voyage. They were therefore entitled to the money. ii) +ractical "enefit! If the performance of an e#isting contractual duty confers a practical "enefit on the other party this can constitute valid consideration. *ee!

:i&&iams v Ro""e$ (1++0) Foffey had a contract to refur"ish a "lock of flats and had su".contracted the carpentry work to >illiams. $fter the work had "egun, it "ecame apparent that >illiams had underestimated the cost of the work and was in financial difficulties. Foffey, concerned that the work would not "e completed on time and that as a result they would fall foul of a penalty clause in their main contract with the owner, agreed to pay >illiams an e#tra payment per flat. >illiams completed the work on more flats "ut did not receive full payment. Ee stopped work and "rought an action for damages. In the Court of $ppeal, Foffey argued that >illiams was only doing what he was contractually "ound to do and so had not provided consideration. It was held that where a party to an e#isting contract later agrees to pay an e#tra 4"onus4 in order to ensure that the other party performs his o"ligations under the contract, then that agreement is "inding if the party agreeing to pay the "onus has there"y o"tained some new practical advantage or avoided a disadvantage. In the present case there were "enefits to Foffey including (a) making sure >illiams continued his work, (") avoiding payment under a damages clause of the main contract if >illiams was late, and (c) avoiding the e#pense and trou"le of getting someone else. Therefore, >illiams was entitled to payment. 3. Part (a 'ent of a !ebt T)e 1enera* ru*e If one person owes a sum of money to another and agrees to pay part of this in full settlement, the rule at common law is that part.payment of a de"t is not good consideration for a promise to forgo the "alance. Thus, if $ owes B 567 and B accepts 536 in full satisfaction on the due date, there is nothing to prevent B from claiming the "alance at a later date, since there is no consideration proceeding from $ to enforce the promise of B to accept part.payment. This is "ased on two reasonings) . Ee is already "ound to pay the full amount, an agreement "ased on the same principle as *tilk v =yrick (017B). . It also protects a creditor from the economic duress of his de"tor. This rule was applied in) ;oa'es v 1eer (188.) + -!! Cas 205 =rs Beer had o"tained &udgment for a de"t against ,r Foakes, who su"se9uently asked for time to pay. *he agreed that she would take no further action in the matter provided that Foakes paid 5677 immediately and the rest "y half.yearly instalments of 5067. Foakes duly kept to his side of the agreement. (udgment de"ts, however, carry interest. The Eouse of 'ords held that =rs Beer was entitled to the 5CG7 interest which had accrued. Foakes had not 4"ought4 her promise to take no further action on the &udgment. Ee had not provided any consideration. This rule has its own e#ceptions which can "e classified as) . +innels case e#ceptions . Common law e#ceptions . :9uity e#ception. promissory estoppel. Exce(tions in Pinne*4s case 5Pinne*4s case exec(tions) In an earlier case that developed the principle, some e#ceptios to this rule were developed! 6

4i e&3s Case (1205) Cole owed +innel 51.07s.7d (51.67) which was due on 00 ovem"er. $t +innel%s re9uest, Cole payed 56.3s.3d (56.00) on 0 -cto"er, which +innel accepted in full settlement of the de"t. +innel sued Cole for the amount owed. It was held that part.payment in itself was not consideration. Eowever, it was held that the agreement to accept part.payment would "e "inding if the de"tor, at the creditor%s re9uest, provided some fresh consideration. Consideration might "e provided if the creditor agrees to accept! The court set out the following e#ceptions) . If +art.payment is made on an earlier date than the due date (ie, as in +innel%s Case itself)) or . If made "y Chattel instead of money (a 4horse, hawk or ro"e4 may "e more "eneficial than money)) or . +art.payment in a different place to that originally specified. . +ayment of a smaller sum in addition to an o"&ect . +ayment of a smaller sum in a different currency Co''on $a6 Exce(tions $part from the e#ceptions to the rule mentioned in +innel%s Case itself, there are two others at common law and one e#ception in e9uity. a) Part-pay ent of the debt by a third party $ promise to accept a smaller sum in full satisfaction will "e "inding on a creditor where the part.payment is made "y a third party on condition that the de"tor is released from the o"ligation to pay the full amount. *ee! 9iracha % 4u amcha % v 6em!&e *1+11, 5 <1 330 $ father paid a smaller sum to a money lender to pay his son%s de"ts, which the money lender accepted in full settlement. 'ater the money lender sued for the "alance. It was held that the part. payment was valid consideration, and that to allow the moneylender%s claim would "e a fraud on the father. b) !o position agree ents The rule does not apply to composition agreements. This is an agreement "etween a de"tor and a group of creditors, under which the creditors agree to accept a percentage of their de"ts (eg, 67p in the pound) in full settlement. ,espite the a"sence of consideration, the courts will not allow an individual creditor to sue the de"tor for the "alance! :oo% v Ro#arts (1818). The reason usually advanced for this rule is that to allow an individual creditor to claim the "alance would amount to a fraud on the other creditors who had all agreed to the percentage. Exce(tion at E-uit Pro issory Estoppel $ further e#ception to the rule in +innel%s Case is to "e found in the e9uita"le doctrine of promissory estoppel. The doctrine provides a means of making a promise "inding, in certain circumstances, in the a"sence of consideration. The principle is that if someone (the promisor) makes a promise, which another person acts on, the promisor is stopped (or estopped) from going "ack on the promise, even though the other person did not provide consideration (in so far as is it is ine9uita"le to do so). G

9igh 6rees (1+.7) In 0BC< the +s granted a BB year lease on a "lock of flats in 'ondon to the ,s at an annual rent of 53677. Because of the out"reak of war in 0BCB, the ,s could not get enough tenants and in 0B27 the +s agreed in writing to reduce the rent to 50367. $fter the war in 0B26 all the flats were occupied and the +s sued to recover the arrears of rent as fi#ed "y the 0BC< agreement for the last two 9uarters of 0B26. ,enning ( held that they were entitled to recover this money as their promise to accept only half was intended to apply during war conditions. This is the ratio decidendi of the case. Ee stated o"iter, that if the +s sued for the arrears from 0B27.26, the 0B27 agreement would have defeated their claim. :ven though the ,s did not provide consideration for the +s% promise to accept half rent, this promise was intended to "e "inding and was acted on "y the ,s. Therefore the +s were estopped from going "ack on their promise and could not claim the full rent for 0B27.26. Thus it seems that if a person promises that he will not insist on his strict legal rights, and the promise is acted upon, then the law will re9uire the promise to "e honoured even though it is not supported "y consideration. F:H;IF:=: T* The e#act scope of the doctrine of promissory estoppel is a matter of de"ate "ut it is clear that certain re9uirements must "e satisfied "efore the doctrine can come into play! (a) Co tractua&=&ega& Re&atio shi! The &udges in the 9igh 6rees case, said that an e#isting contractual relationship was necessary. Eowever this has "een modified in later cases holding that itIs not necessary provided there was 4a pre.e#isting legal relationship which could, in certain circumstances, give rise to lia"ilities and penalties4. (#) 4romise There must "e a clear and unam"iguous statement "y the promisor that his strict legal rights will not "e enforced, i.e. one party must make a promise which is intended to "e "inding. Eowever, it needs not "e e#press "ut can "e implied or made "y conduct. (c) Re&ia ce The promisee must have acted in reliance on the promise. There is some uncertainty as to whether the promisee (i) *hould have relied on the promise "y changing his position to their detriment (ie, so that he is put in a worse position if the promise is revoked). or (ii) >hether they should have merely altered their position in some way, not necessarily for the worse. 'ater cases have clarified that the only thing re9uired is that the party must have "een led to act differently from what he otherwise would have done. (%) > e?uita#&e to revert It must "e ine9uita"le for the promisor to go "ack on his promise and revert to his strict legal rights. If the promisor%s promise has "een e#tracted "y improper pressure it will not "e ine9uita"le for the promisor to go "ack on his promise. *ee! ( @ C 1ui&%ers v Rees *1+25, 5 A1 217 The +s, a small "uilding company, had completed some work for =r Fees for which he owed the company 5213. For months the company, which was in severe financial difficulties, pressed for <

payment. :ventually, =rs Fees, who had "ecome aware of the company%s pro"lems, contacted the company and offered 5C77 in full settlement. *he added that if the company refused this offer they would get nothing. The company reluctantly accepted a che9ue for 5C77 4in completion of the account4 and later sued for the "alance. The Court of $ppeal held that the company was entitled to succeed. 'ord ,enning was of the view that it was not ine9uita"le for the creditors to go "ack on their word and claim the "alance as the de"tor had acted ine9uita"ly "y e#erting improper pressure. (e) - shie&% or a s/or%B $t one point it was said in) Coom#e v Coom#e That the doctrine may only "e raised as a defence! 4as a shield and not a sword4. It was held that the doctrine cannot "e raised as a cause of action. This means that the doctrine only operates as a defence to a claim and cannot "e used as the "asis for a case. 'ately, &udges have adopted an opposite opinion, holding that it could create rights. (") Exti ctive or )us!e sive o" rightsB $nother 9uestion raised "y this doctrine is whether it e#tinguishes rights or merely suspends them. The prevalent authorities are in favour of it merely suspending rights, which can "e revived "y giving reasona"le notice or "y conditions changing. . >here the de"tor%s contractual o"ligation is to make periodic payments, the creditor%s right to receive payments during the period of suspension may "e permanently e#tinguished, "ut the creditor may revert to their strict contractual rights either upon giving reasona"le notice, or where the circumstances which gave rise to the promise have changed as in 9igh 6rees case . It is not settled law that there can "e no such resumption of payments in relation to a promise to forgo a single sum. The preferred approach is to look at the nature of the promise! if as in Eigh Trees, it is intended to "e temporary in application and to reserve to the promisor the right su"se9uently to reassert his strict legal rights, the effect will "e suspensive only. If on the other hand, it is intended to "e permanent, then there is no reason why in principle or authority the promise should not "e given its full effect so as to e#tinguish the promisor%s right. c) INTENTION 7 TO CREATE $E%A$ RE$ATIONS JTo offer a friend a meal is not to invite litigation/ (Cheshire and foot). $gain, it is a 9uestion of construction as to whether a 4letter of intent4 is the contractual agreement or whether it is merely an e#pression of pious hope, with no contractual force. The law divides agreements into two groups, social K domestic agreements and "usiness agreements. SOCIA$ AND DO,ESTIC A%REE,ENTS Socia* a1ree'ents This group covers agreements "etween, friends and workmates. The law (resu'es that social agreements are not intended to "e legally "inding. *ee, for e#ample!

Le s v (evo shire C&u# (1+1.) It was held that the winner of a competition held "y a golf clu" could not sue for his pri?e where 4no one concerned with that competition ever intended that there should "e any legal results flowing from the conditions posted and the acceptance "y the competitor of those conditions Eowever, if it can "e shown that the transaction had the opposite intention, the court may "e prepared to re"ut the presumption and to find the necessary intention for a contract. The cases show it is a difficult task to re"ut such a presumption. Do'estic a1ree'ents $greements "etween a hus"and and wife living together as one household are presumed not to "e intended to "e legally "inding, unless the agreement states to the contrary. *ee! 1a&"our v 1a&"our (1+1+) The defendant who worked in Ceylon, came to :ngland with his wife on holiday. Ee later returned to Ceylon alone, the wife remaining in :ngland for health reasons. The defendant promised to pay the plaintiff 5C7 per month as maintenance, "ut failed to keep up the payments when the marriage "roke up. The wife sued. It was held that the wife could not succeed "ecause! (0) she had provided no consideration for the promise to pay 5C7) and (3) agreements "etween hus"ands and wives are not contracts "ecause the parties do not intend them to "e legally "inding. The presumption against a contractual intention will not apply where the spouses are not living together in amity at the time of the agreement. *ee! Merrit v Merrit (1+70) The hus"and left his wife. They met to make arrangements for the future. The hus"and agreed to pay 527 per month maintenance, out of which the wife would pay the mortgage. >hen the mortgage was paid off he would transfer the house from &oint names to the wife%s name. Ee wrote this down and signed the paper, "ut later refused to transfer the house. It was held that when the agreement was made, the hus"and and wife were no longer living together, therefore they must have intended the agreement to "e "inding, as they would "ase their future actions on it. This intention was evidenced "y the writing. The hus"and had to transfer the house to the wife. If a domestic agreement will have serious conse9uences for the parties, this may re"ut the presumption. *ee! 4ar'er v C&ar'e (1+20) =rs +arker was the niece of =rs Clarke. $n agreement was made that the +arkers would sell their house and live with the Clarkes. They would share the "ills and the Clarkes would then leave the house to the +arkers. =rs Clarke wrote to the +arkers giving them the details of e#penses and confirming the agreement. The +arkers sold their house and moved in. =r Clarke changed his will leaving the house to the +arkers. 'ater the couples fell out and the +arkers were asked to leave. They claimed damages for "reach of contract. It was held that the e#change of letters showed the two couples were serious and the agreement was intended

to "e legally "inding "ecause (0) the +arkers had sold their own home, and (3) =r Clarke changed his will. Therefore the +arkers were entitled to damages. It seems that agreements of a domestic nature "etween parent and child are likewise presumed not to "e intended to "e "inding. *ee! Co es v 4a%avatto (1+2+) In 0BG3, =rs (ones offered a monthly allowance to her daughter if she would give up her &o" in $merica and come to :ngland and study to "ecome a "arrister. Because of accommodation pro"lems =rs (ones "ought a house in 'ondon where the daughter lived and received rents from other tenants. In 0BG< they fell out and =rs (ones claimed the house even though the daughter had not even passed half of her e#ams. It was held that the first agreement to study was a family arrangement and not intended to "e "inding. :ven if it was, it could only "e deemed to "e for a reasona"le time, in this case five years. The second agreement was only a family agreement and there was no intention to create legal relations. Therefore, the mother was not lia"le on the maintenance agreement and could also claim the house. >here the parties to the agreement share a household "ut are not related, the court will e#amine all the circumstances. *ee! )im!'i s v 4a$s (1+55) The defendant, her granddaughter, and the plaintiff, a paying lodger shared a house. They all contri"uted one.third of the stake in entering a competition in the defendant%s name. -ne week a pri?e of 5<67 was won "ut on the defendant%s refusal to share the pri?e, the plaintiff sued for a third. It was held that the presence of the outsider re"utted the presumption that it was a family agreement and not intended to "e "inding. The mutual arrangement was a &oint enterprise to which cash was contri"uted in the e#pectation of sharing any pri?e. 8#SINESS9CO,,ERCIA$ A%REE,ENTS In "usiness agreements the presumption is that the parties intend to create legal relations and make a contract. This presumption can "e re"utted "y the inclusion of an e#press statement to that effect in the agreement. *ee! Rose v Crom!to 1ros (1+55) The defendants were paper manufacturers and entered into an agreement with the plaintiffs where"y the plaintiffs were to act as sole agents for the sale of the defendant%s paper in the ;*. The written agreement contained a clause that it was not entered into as a formal or legal agreement and would not "e su"&ect to legal &urisdiction in the courts "ut was a record of the purpose and intention of the parties to which they honoura"ly pledged themselves, that it would "e carried through with mutual loyalty and friendly co.operation. The plaintiffs placed orders for paper which were accepted "y the defendants. Before the orders were sent, the defendants terminated the agency agreement and refused to send the paper. It was held that the sole agency agreement was not "inding owing to the inclusion of the 4honoura"le pledge clause4. Fegarding the orders which had "een placed and accepted, however, contracts had "een created and the defendants, in failing to e#ecute them, were in "reach of contract.

07

*imilarly, foot"all pools stated to "e 4"inding in honour only4 are not legal contracts so that a participant may not recover his winnings. *ee! Co es v Der o 4oo&s (1+38) The plaintiff claimed to have won the foot"all pools. The coupon stated that the transaction was 4"inding in honour only4. It was held that the plaintiff was not entitled to recover "ecause the agreement was "ased on the honour of the parties (and thus not legally "inding). Contractual intention may "e negatived "y evidence that 4the agreement was a goodwill agreement K made without any intention of creating legal relations4 If a clause is put in an agreement and the clause is am"iguous then the courts will intervene and interpret it. *ee! E%/ar%s v )'$/a$s (1+2.) The plaintiff pilot was made redundant "y the defendant. Ee had "een informed "y his pilots association that he would "e given an e# gratia payment (ie, a gift). The defendant failed to pay and the pilot sued. The defendant argued that the use of the words 4e# gratia4 showed that there was no intention to create legal relations. It was held that this agreement related to "usiness matters and was presumed to "e "inding. The defendants had failed to re"ut this presumption. The court also stated that the words 4e# gratia4 or 4without admission of lia"ility4 are used simply to indicate that the party agreeing to pay does not admit any pre. e#isting lia"ility on his part) "ut he is certainly not seeking to preclude the legal enforcea"ility of the settlement itself "y descri"ing the payment as 4e# gratia4. Contractual intention may nonetheless "e negated "y the vagueness of a statement or promise. C9 Mi& er v 4erc$ 1i&to (1+22) $ property developer reached an 4understanding4 with a firm of solicitors to employ them in connection with a proposed development, "ut neither side entered into a definite commitment. The use of deli"erately vague language was held to negative contractual intention. !) FOR, For an agreement to constitute a valid and enforcea"le contract it must have "een entered into in the form, or 'anner, if any, (rescribe! "y law. The general rule at co''on *a6 is that a contract can "e entered into orally, in writing, partly orally and partly in writing, or may "e merely implied from conduct! Re-uire'ents of 6ritin1 Contracts re9uired to "e in writing include) :8i**s of Exc)an1e an! Pro'issor Notes+ The Bills of :#change $ct defines a "ill of e#change as, an unconditional or!er in 6ritin1 ....4 The $ct further states that an instrument which does not co'(* with these conditions ... is not a "ill of e#change. To "e valid, therefore, a "ill of e#change must "e made in writing. This re9uirement also applies to +romissory otes under *. 12(0) of the Bills of :#change $ct. :Re(resentations Re1ar!in1 C)aracter or Cre!it+ *tatements relating to a person%s credit. worthiness will only "e actiona"le if made in pursuance of a contract which was in writing. This is per the 'aw of Contract $ct, *.C(3) :Transfer of S)ares In A Co'(an Re1istere! #n!er T)e Co'(anies Act! *ection << of the Companies $ct prohi"its an incorporated company from registering any transfer of shares 00

or de"entures of the company unless a proper instrument of transfer has "een delivered to the company. :Ac;no6*e!1e'ent of Statute 8arre! Debts! If an action for a simple contract de"t has "een "arred "y the limitation period of si# years, it is possi"le for the right of action to "e revived "y an acknowledgement or part payment. *.32 of the 'imitation of $ctions $ct, 0BG1 provides that for such an acknowledgement to "e effective it must "e in 6ritin1 and signed "y the person making it, or his agent. :Transfer of I''o/ab*e Pro(ert ! *.62 of the Indian Transfer of +roperty $ct, 0113 ( ote! This $ct is applica"le in Lenya) re9uires that a transfer of i''o/ab*e (ro(ert worth over 077 rupees must "e "y a re1istere! instru'ent. The re9uirement of registration makes a written document necessary.. The a"ove contracts are void unless they are made in writing Re-uire'ent of 6ritten e/i!ence These contracts must "e evidenced "y some note or memorandum : Contracts of %uarantee! The 'aw of Contract $ct, 0BG0, *.C (0) provides! <No suit s)a** be brou1)t where"y to charge the defendant upon any special promise to answer for the de"t, default or miscarriage of another person un*ess t)e a1ree'ent upon which such suit is "rought, or some memorandum or note thereof, is in 6ritin1 and signed "y the party to "e charged therewith, or other persons thereunto "y him lawfully authori?ed.4 : Contracts For T)e Sa*e Of An Interest In $an!! The 'aw of Contract ($mendment) $ct, 0BG1, provides! 4No suit s)a** be brou1)t upon a contract for the disposition of an interest in *an! unless the agreement upon which the suit is founded, or some memorandum or note thereof is in 6ritin1 and is signed "y the party to "e charged or "y some person authorised "y him to sign it. +rovided that such a suit shall not "e prevented "y reason only of the a"sence of writing, where an intending purchase or lessee who has performed or is willing to perform his part of a contract : E'(*o 'ent Contracts for O/er One ,ont)+ ;nder *.6 of the :mployment $ct 377G. e) CAPACITY MCapacity% may "e descri"ed as the legally recogni?ed right of a person to enter into a legally "inding agreement. The law of contract limits in varying degrees the contractual capacity of the following persons! o =inors o ,runkards o +eople suffering mental incapacity o Corporations . sue and "e sued ,inors $n infant or a minor is any person who has not attained the age of eighteen years! $ge of =a&ority $ct 0B<2 *3. Eere the contracts are of three types Nalid contracts @ enforcea"le against the minor Noida"le contracts @ the minor may enter into and possi"le continue with, "ut also can avoid or set aside. Noid contracts @ those that can never "e enforced against the minor 03

"alid and enforceable against inors o Contracts for necessaries o Contracts for service, training or education 7ecessaries $ minor must pay a reasona"le sum for necessaries actually delivered. % ecessaries% are defined "y *. 2(3) of the *ale of Doods $ct as 4goods suita"le to the condition in life of such infant or minor... and to his actual re9uirements at the time of sale and delivery4. ecessaries would thus "e those things that a person immediately needs, such as food) drink) clothing) accommodation) medicines. ecessaries are not confined to those things which are a"solutely re9uired to keep him alive "ut they e#tend to all such things as are reasona"ly necessary for him in the station in life to which he "elongs. They e#clude lu#uries, and also a surplus of necessary items (e.g. a contract to "uy two shirts would, pro"a"ly, "e "inding "ut one for a do?en would not "e.) 7ash v. > ma (1+08) The claimant was a >est :nd tailor and the defendant was a minor undergraduate at Trinity College, Cam"ridge. The claimant sued the minor for the price of various items of clothing, including eleven fancy waistcoats. It was proved that the defendant was well supplied with such clothes when the claimant delivered the clothing in 9uestion. $ccordingly, the claimant%s action failed "ecause he had not esta"lished that the clothes supplied were necessaries. The a"ove case 7ash v > ma 1+08 propagates a two part test i.e. . ecessary "y the minorIs station in life and necessary for the minorIs actual current needs. . :ven if for necessaries, minor may not "e "ound if contract terms are pre&udicial to minorIs interests. *. 2(0) of the *ale of Doods $ct provides that the infant is lia"le to pay 4a reasona"le price4 for necessaries supplied to him. Ee is not lia"le for the agreed price. )ervice, trai i g or e%ucatio *uch contract is only enforcea"le if su"stantially for the minorIs "enefit. If contract declared to "e not for their "enefit its voida"le "y the minor. Court looks at contract as whole @ isolated terms not to the minorIs "enefit will not necessarily invalidate the contract. 8uara tees For Duarantees, the 'aw of Contract $ct allows enforcement of guarantee. >here an adult guarantees a loan to a minor then, prior to 0B1<, that guarantee would "e treated as unenforcea"le. ow, however, *ection 3 of the ,inors= Contracts Act 1>?3 provides that such a guarantee shall no longer "e treated as unenforcea"le merely "ecause the contract with the minor cannot "e enforced. "oidable by inors Common feature is long term @ continuous or recurring o"ligations 2 types of such contracts include! lease of property, purchase of shares in a company, entering a partnership and marriage settlements. Leases

0C

$ lease granted to an infant is "inding on him unless he repudiates it within a reasona"le time after attaining the age of eighteen. (avies v. 1e$ o E 9arrisF The court held that an infant tenant was lia"le for the rent of a flat which had accrued "efore he repudiated the lease. 4art ershi! -greeme t $n infant is "ound at common law "y a partnership agreement "ut he is free to repudiate it at any time during infancy or within a reasona"le time after attaining his ma&ority. 4urchase o" )hares $n infant who applies for, and is allotted, a company%s shares "ecomes a mem"er of the company under *.31 (3) of the Companies $ct from the moment that his name is entered in the register of mem"ers. Ee then ac9uires mem"ership rights and "ecomes su"&ect to mem"ership o"ligations like any other mem"er. Eowever, he has a legal right to rescind the contract if there has "een a total failure of consideration for which he paid the money (i.e. the shares have "ecome worthless). =ost contracts with a minor are 4voida"le4 at her option. That is to say, she but not t)e ot)er (art , has the right not to "e "ound "y the contract. To "e voida"le, she must repudiate the contract during her minority, or within a reasona"le time after reaching her ma&ority. If not, the contract will "ecome "inding. If the minor repudiates "efore o"ligations arise @ contract simply ceases. Eowever she may still "e "ound "y o"ligations arising "efore repudiation. =oney transferred under the agreement is not recovera"le unless there is a failure of consideration !ontracts void and unenforceable against inors Contracts such as) 'oans of money, *upply of goods and services other than necessaries and I-;s are unenforcea"le against the minors. Though not enforcea"le against the minor they are enforcea"le against the other party. =inor can only recover money paid if there is a failure of consideration If minor ratifies (e#press or implied) after 01 the minor then "ound. *ome contracts are, "y statute, unenforcea"le against a minor. For e#ample, under the Consu'er Cre!it Act 1>34 it is an offence to send literature to a minor inviting himOher to "orrow money or o"tain goods or services on credit. $n e#ception to this general rule e#ists where the money "orrowed has "een used for the purchase of necessaries (see "elow). In this case the lender can recover such part of the loan as was actually spent on necessaries. Drun;enness an! ca(acit $ party who enters a contract while drunk @ contract may "e unenforcea"le. This is "ecause the party must not have known the 9uality of his actions at the time the contract was formed. The general rule is thus summari?ed that e#cept for contracts for necessaries, contracts are not "inding on such persons, unless they specifically ratify them when so"er. The other party must have known of the into#ication. Contract is voida"le when drunken party is so"er Eowever) . The party may ratify agreement when. *C *ale of Doods $ct . $ drunken person is lia"le to pay for necessaries supplied to him pursuant to a contract which he entered into when too drunk to know what he was doing 02

If incapacitated "y drink, need only pay a reasona"le price for goods delivered, not the agreed price to avoid e#ploitation.

,enta* inca(acit The capacity to enter into contracts with mentally ill people is still mainly governed "y common law. Court must decide if, when contract formed, person capa"le of understanding their act. Contract is voida"le "y person lacking mental capacity. The general rule is thus summari?ed as e#cept for contracts for necessaries, contracts are not "inding on such persons, unless they specifically ratify them during a lucid period. Eowever, other party must have known of mental incapacity @ if not, then contract will "e &udged "y same standards as if contract "etween persons of sound mind. *C *ale of Doods $ct further provides that) . Contract for necessaries are valid @ For the valid contracts, person need only pay a reasona"le price for goods delivered even if other person not aware of mental illness . The mentally ill person can ratify the contract during a lucid period i.e when heOshe is so"er Cor(orations Contracts are affected "y ;ltra vires rule. s.C6 Companies $ct provides that an act is not invalidated merely "ecause it is "eyond the companyIs capacity @ and further, there is no duty to en9uire whether or not the transaction is allowed "y the companyIs o"&ects clause f) I$$E%A$ITY For an agreement to constitute a legally enforcea"le contract, it must have "een entered into for a lawful purpose. $n agreement to do something which is prohi"ited "y statute or the common law is not a contract . although such agreements are generally called 4illegal contracts4 I**e1a* Contracts There are numerous e#amples of 4illegal contracts4 of which the following may "e mentioned! : Contracts i**e1a* b statute! >hether a particular contract is prohi"ited "y a particular statute depends on the wording of the statute. For e#ample, employment act, contracts for the payment of wages or salaries in kind are illegal. : Contracts i**e1a* at t)e co''on *a6! $ contract which is prohi"ited "y the common law is usually descri"ed as "eing 4contrary to pu"lic policy4 (i.e. the court is of the view that it is in the pu"lic interest that the contract should not "e enforced). *uch a contract may "e one which! (i) Tends to promote corruption in the pu"lic service (ii) Tends to promote se#ual immorality (iii) Tends to interfere with the sanctity of marriage. (iv) Tends to fetter the freedom of marriage. (v) Tends to pre&udice the administration of &ustice, such as . (a) Champerty, or (") =aintenance. 06

Effects or !onsequences of #llegality Illegality renders a contract unenforcea"le. The contract creates no rights and imposes no o"ligations on the parties. This is "ecause the contract is "eyond the pale of law hence neither party has a legal remedy. $s a general rule money or goods changing lands under an illegal contract are irrecovera"le. This is "ecause gains and losses remain where they have fallen. $ court of law cannot assist parties to ad&ust their rights if the contract is tainted with illegality. Eowever money or goods changing hands under an illegal contract may "e recovera"le where (a) a party repents or regrets the illegality "efore the contract is su"stantially performed. (") The parties are not in pari delicto i.e. not e9ually to "lame. (c) The owner of the goods or money esta"lishes title thereto without relying upon the illegal contract &oi! Contracts These are contracts which the law treats as non.e#istent. $s a general rule illegal contract is only void "ut not certain rights may "e salvaged "y the innocent party. $ contract may "e rendered "y statute or at common law i.e. courts of law. Contracts /oi! b t)e statute. . >agering contract.! This is a contract where"y two persons or groups of persons with different views on the outcome of an uncertain future event agree that some consideration is to pass depending on the outcome. . Contracts in restraint of trade! This is a contract "y which a person voluntarily or involuntarily restricts his future li"erty to carry on his trader "usiness or profession in such manner or with such persons as he chooses e.g. an employer restraining an employee from working for a "usiness rival. The principles or rules governing contracts in restraint of trade in Lenya are contained in the Contracts in Festraint of trade $ct under sec.3 of the act contracts in restraint of trade in Lenya are legally "inding, however the Eigh court is empowered to declare such a contract void if it is satisfied that the restraint is unreasona"le in that it affords more protection than necessary or is in&urious to the pu"lic. To make its decision the court must have regard to a. The nature of trade, "usiness, occupation or professional ". $rea covered "y the restraint c. ,uration of the restraint d. -ther circumstances of the case Contracts /oi! at co''on *a6 These are contracts declared void "y courts of law for "eing contrary to pu"lic policy namely . Contract of the courts . Contract pre&udicial to the statute of marriage 1) FREE FRO, &ITIATIN% FACTORS The contract must "e free from vitiating factors. These factors include! 0G

,uress! threat of illegal actions either on your person, your family or your property, aimed at forcing you to sign the contract. *uch conduct makes the contract void. ;ndue influence! Taking advantage of a close relationship "ased on trust to mislead a person to enter into a contract. :.g. mentor.mentee, pastor.congregation mem"er etc. *uch will make the contract voida"le. =istake! this is where you enter into a contract "ased on wrong assumptions. It may "e a mistake as to su"&ect matter e.g. model of a vehicle, mistake as to identity e.g. dealing with the wrong person, or mistake as to the terms of the contract e.g. price. =isrepresentation! this is where a person is misled to sign a contract "y false representationsOfalse statements. If the a"ove factors are present, they take away the consent that was given, making the consent to "e invalid. This then means the contract itself is invalid.

0<

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- IMF and AML PDFDocument3 pagesIMF and AML PDFFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Money Laundering Methods in East and Southern Africa PDFDocument20 pagesMoney Laundering Methods in East and Southern Africa PDFFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Misuse of NGOs For Money LaunderingDocument6 pagesMisuse of NGOs For Money LaunderingFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Money Laundering in KenyaDocument92 pagesChapter 4 - Money Laundering in KenyaFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Control of Money Laundering in KenyaDocument73 pagesChapter 3 - Control of Money Laundering in KenyaFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Fighting Money Laundering in AfricaDocument12 pagesFighting Money Laundering in AfricaFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Extradition of Okemo and GichuruDocument2 pagesExtradition of Okemo and GichuruFrancis Njihia Kaburu100% (1)

- Land Ownership in IslamDocument17 pagesLand Ownership in IslamFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Land ReportDocument32 pagesLand Reportjaffar s m100% (1)

- The Concept of Land Ownership: Islamic PerspectiveDocument20 pagesThe Concept of Land Ownership: Islamic Perspectivemohkim100% (1)

- Swynnerton Plan 1954Document2 pagesSwynnerton Plan 1954OnyangoVictor71% (7)

- Regulation of Use of Private Land in KenyaDocument24 pagesRegulation of Use of Private Land in KenyaFrancis Njihia Kaburu100% (1)

- Kenya Land Policy AnalysisDocument51 pagesKenya Land Policy AnalysisFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Concept of Land Ownership in KenyaDocument14 pagesConcept of Land Ownership in KenyaFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Decentralization in Africa ReportDocument46 pagesDecentralization in Africa ReportFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Land Titles at Kenyan CoastDocument41 pagesLand Titles at Kenyan CoastFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Endorois DecisionDocument80 pagesEndorois DecisionFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Squatters at CoastDocument135 pagesSquatters at CoastFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- LSK Conditions of SaleDocument13 pagesLSK Conditions of SaleFrancis Njihia Kaburu0% (1)

- Colony and Protectorate of Kenya Land Tenure CommissionDocument12 pagesColony and Protectorate of Kenya Land Tenure CommissionFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Grabbing of Beach Plots in KenyaDocument3 pagesGrabbing of Beach Plots in KenyaFrancis Njihia Kaburu100% (2)

- Devolution in Kenya Setting The Agenda e VersionDocument54 pagesDevolution in Kenya Setting The Agenda e VersionSamuel Ngure100% (1)

- Defences in Criminal LawDocument13 pagesDefences in Criminal LawFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Self Regulation in Capital MarketsDocument12 pagesSelf Regulation in Capital MarketsFrancis Njihia Kaburu0% (1)

- Refusal To Deal in The EUDocument32 pagesRefusal To Deal in The EUFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Kenya Wildlife Conservation and Management Act 2013Document116 pagesKenya Wildlife Conservation and Management Act 2013Francis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Retail Price Maintenance - Leggin CaseDocument55 pagesRetail Price Maintenance - Leggin CaseFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Handout 1 - Homicide OffencesDocument20 pagesHandout 1 - Homicide OffencesFrancis Njihia Kaburu75% (4)

- Kenya Tourism Act 2011Document72 pagesKenya Tourism Act 2011Francis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Kenya National Tourism Srategy 2013 - 2018Document46 pagesKenya National Tourism Srategy 2013 - 2018Francis Njihia Kaburu67% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Purification of Dilactide by Melt CrystallizationDocument4 pagesPurification of Dilactide by Melt CrystallizationRaj SolankiNo ratings yet

- Motion To Dismiss Guidry Trademark Infringement ClaimDocument23 pagesMotion To Dismiss Guidry Trademark Infringement ClaimDaniel BallardNo ratings yet

- 5 24077 Rev2 PDFDocument3 pages5 24077 Rev2 PDFJavier GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Depreciation - Sum of The Years Digit MethodPart 4Document8 pagesChapter 3 Depreciation - Sum of The Years Digit MethodPart 4Tor GineNo ratings yet

- 2 Calculation ProblemsDocument4 pages2 Calculation ProblemsFathia IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Ebook Stackoverflow For ItextDocument336 pagesEbook Stackoverflow For ItextAnonymous cZTeTlkag9No ratings yet

- TRAVEL POLICY CARLO URRIZA OLIVAR Standard Insurance Co. Inc - Travel Protect - Print CertificateDocument4 pagesTRAVEL POLICY CARLO URRIZA OLIVAR Standard Insurance Co. Inc - Travel Protect - Print CertificateCarlo OlivarNo ratings yet

- Kamal: Sales and Marketing ProfessionalDocument3 pagesKamal: Sales and Marketing ProfessionalDivya NinaweNo ratings yet

- Subject: PSCP (15-10-19) : Syllabus ContentDocument4 pagesSubject: PSCP (15-10-19) : Syllabus ContentNikunjBhattNo ratings yet

- IEEE 802 StandardsDocument14 pagesIEEE 802 StandardsHoney RamosNo ratings yet

- Earth and Life Science, Grade 11Document6 pagesEarth and Life Science, Grade 11Gregorio RizaldyNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh Distilers N BotlersDocument3 pagesChandigarh Distilers N BotlersNipun GargNo ratings yet

- Technology ForecastingDocument38 pagesTechnology ForecastingSourabh TandonNo ratings yet

- Catch Up RPHDocument6 pagesCatch Up RPHபிரதீபன் இராதேNo ratings yet

- 1 - DIASS Trisha Ma-WPS OfficeDocument2 pages1 - DIASS Trisha Ma-WPS OfficeMae ZelNo ratings yet

- Heat Pyqs NsejsDocument3 pagesHeat Pyqs NsejsPocketMonTuberNo ratings yet

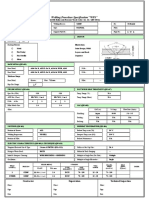

- Wps For Carbon Steel THK 7.11 GtawDocument1 pageWps For Carbon Steel THK 7.11 GtawAli MoosaviNo ratings yet

- Presentación de Power Point Sobre Aspectos de La Cultura Inglesa Que Han Influido en El Desarrollo de La HumanidadDocument14 pagesPresentación de Power Point Sobre Aspectos de La Cultura Inglesa Que Han Influido en El Desarrollo de La HumanidadAndres EduardoNo ratings yet

- ISSA2013Ed CabinStores v100 Часть10Document2 pagesISSA2013Ed CabinStores v100 Часть10AlexanderNo ratings yet

- OM Part B - Rev1Document45 pagesOM Part B - Rev1Redouane BelaassiriNo ratings yet

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm - Strickland, Lloyd - Leibniz's Monadology - A New Translation and Guide-Edinburgh University Press (2014)Document327 pagesLeibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm - Strickland, Lloyd - Leibniz's Monadology - A New Translation and Guide-Edinburgh University Press (2014)Gigla Gonashvili100% (1)

- EPA Section 608 Type I Open Book ManualDocument148 pagesEPA Section 608 Type I Open Book ManualMehdi AbbasNo ratings yet

- Volcano Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesVolcano Lesson Planapi-294963286No ratings yet

- Full Download Ebook PDF Introductory Econometrics A Modern Approach 7th Edition by Jeffrey PDFDocument42 pagesFull Download Ebook PDF Introductory Econometrics A Modern Approach 7th Edition by Jeffrey PDFtimothy.mees27497% (39)

- Master Data FileDocument58 pagesMaster Data Fileinfo.glcom5161No ratings yet

- PRINCIPLES OF TEACHING NotesDocument24 pagesPRINCIPLES OF TEACHING NotesHOLLY MARIE PALANGAN100% (2)

- Model 900 Automated Viscometer: Drilling Fluids EquipmentDocument2 pagesModel 900 Automated Viscometer: Drilling Fluids EquipmentJazminNo ratings yet

- Aqa Ms Ss1a W QP Jun13Document20 pagesAqa Ms Ss1a W QP Jun13prsara1975No ratings yet

- 2012 Conference NewsfgfghsfghsfghDocument3 pages2012 Conference NewsfgfghsfghsfghabdNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument22 pagesProjectSayan MondalNo ratings yet