Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eco Essay T Intern

Uploaded by

Cathal O' GaraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eco Essay T Intern

Uploaded by

Cathal O' GaraCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

Ecocriticism: Relevance of William Wordsworths Tintern Abbey and The World is too Much with Us. M.A.AFZAL FAROOQ N. D. R. CHANDRA

Abstract: Ecocriticism addresses how humans relate to non-human nature or the environment in literature. It has grown out of the traditional approach to literature in which the critic explores the local or global, the material or physical, or the historical or natural history in the context of a work of art. This paper is a modest attempt to unearth the concerns of ecocriticism as well as to explore William Wordsworth's contribution to the awakening of modern man towards conservation and preservation of the ecosystem. All ecocritics share an environmentalist motivation in one way or the other. . As a result of want of systematic or organized movement in the study of ecological or environmental side of literature, the ecocritical works came to be nomenclatured variously such as pastoralism, human ecology, regionalism, American Studies etc. Raymond Williams, the British Marxist critic wrote The Country and the City (1973), where he professed a decidedly green socialism. Ecocriticism analyzes the role that the natural environment plays in the imagination of a cultural community at a specific historical moment, examining how the concept of "nature" is defined, what values are assigned to it or denied it and why, and the way in which the relationship between humans and nature is envisioned. Wordsworth advocated for the preservation of Nature way back in the 18th century. Besides divinizing Nature, Wordsworth pleaded that it is a panacea for all with the capacity to elevate human mind to a higher level of feeling for everything in Nature. Tintern Abbey exposes Wordsworth's development of love for Nature through various stages and inevery stage there was a need to preserve it because it helps in developing the mind, attitude and feeling. The World is Too Much with Us is an exploration of the poet's dissatisfaction of the modern men over their indifference to and indiscriminate destruction of Nature. Keywords: Ecocriticism, Green (Cultural) Studies, ecopoetics, environmental literary criticism, Pantheism, Panacea.

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

113

I Ecocriticism as a distinct subject of study in the institutes of higher education received due importance relatively recently. The unprecedented degradation of the ecosystem threatening the very existence of human race awakened the world to think seriously about the conservation of environment. The depletion of the ozone layer, incurable diseases emanating from environmental pollution and myriads of similar factors led the intellectuals to ponder over the hazards and find out some means to promote the campaign of saving nature through literature and other media. Ecocriticism addresses how humans relate to non- human nature or the environment in literature. It has grown out of the traditional approach to literature in which the critic explores the local or global, the material or physical, or the historical or natural history in the context of a work of art. This paper is a modest attempt to unearth the concerns of ecocriticism as well as to explore William Wordsworths contribution to the awakening of modern man towards conservation and preservation of the ecosystem. Ecocriticism Defined Ecocriticism implies the study of literature and environment from an interdisciplinary point of view. It is also referred to as green criticism, green (cultural) studies, ecopoetics and environmental literary criticism. Ecocriticism has contributed significantly to the evolution of environmentalist thought since 1960s. It was officially prognosticated by the publication of two seminal works, both published in the mid-1990s: The Ecocriticism Reader, edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm and The Environmental Imagination, by Lawrence Buell. As a critical mode of study, ecocriticism looks back on a long tradition of criticism that approaches nature as an aesthetic and not a scientific object, and that often sees scientific analysis as detrimental to aesthetic appreciation. Glotfelty defines ecocriticism in The Ecocriticism Reader as the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment (1996: xviii). An implicit aim of this approach is to

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

114

recoup professional dignity for what Glotfelty calls the undervalued genre of nature writing (Ibid: xxxi) According to Buell, ecocriticism is a study of the relationship between literature and the environment conducted in a spir it of commitment to environmentalist praxis (1995: 430). Buells definition emphasizes that ecocriticism is about the relationship existing between literature and the environment or the ecology. Simon Estok points out, ecocriticism has distinguished itself, debates notwithstanding, firstly by the ethical stand it takes, its commitment to the natural world as an important thing rather than simply as an object of thematic study, and secondly, by its commitment to making connections (2001: 220). Estok further says that ecocriticism is more than simply the study of Nature or natural things in literature; rather, it is any theory that is committed to effecting change by analyzing the function thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise, of the natural environment, or aspects of it, represented in documents (literary or other) that contribute to material practices in material worlds (2005:16-17). In response to the question of what ecocriticism is or should be, Camilo Gomides offers an operational definition that is both broad and discriminating: The field of enquiry that analyses and promotes works of art which raise moral questions about human interactions with nature, while also motivating audiences to live within a limit that will be binding over generations (2006:16). Gomides definition led Joseph Henry Vogel to conclude that ecocriticism constitutes an economic school of thought as it engages audiences to debate issues of resource allocation that have no technical solution. Thus, ecocriticism has been defined in various ways by various scholars. The common point where all the critics meet is their agreement on the fact that ecocriticism studies the earth, the environment and the ecosystem and express their concern about the preservation of the jeopardized ecology we are living in and how literary discourses view the ecocritical writings. Evolution of Ecocriticism in Literature With intent to focus on the application of ecology and ecological concepts to the study of literature, William Rueckert

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

115

published an essay entitled Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism. As a result of want of systematic or organized movement in the study of ecological or environmental side of literature, the ecocritical works came to be nomenclatured variously such as pastoralism, human ecology, regionalism, American Studies etc. Raymond Williams, the British Marxist critic wrote The Country and the City (1973), where he professed a decidedly green socialism. Joseph Meekers book The Comedy of Survival (1974) says that the environmental crisis is caused primarily by a cultural tradition in the West of separation of culture from nature and elevation of the former to moral predominance(1974:126). Such anthropocentrism is identified in the tragic conception of a hero whose moral struggles are more important than mere biological survival, whereas the science of animal ethology, Meeker asserts, shows that a comic mode of muddling through and making love not war has superior ecological value. Glotfelty says, One indication of the disunity of the early efforts is that these critics rarely cited one anothers work; they did not know that it existed Each was single voice howling in the wilderness(2006:76). Nevertheless, ecocriticism unlike the Marxist criticisms failed to crystallize into a coherent movement in the late 1970s, and indeed only did so in the USA in the 1990s. In the mid1980s, scholars began to work collectively to establish ecocriticism as a genre, primarily through the work of the Western Literature Association in which the revolution of nature writing as a non-fictional literary genre could function. In 1990, at the University of Nevada in Reno, Glotfelty became the first person to hold an academic position as a Professor of Literature and the Environment, and UNR has retained the position it established at that time as the intellectual home of ecocriticism even as Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) has burgeoned into an organization with thousands of members in the USA alone. From the late 1990s, new branches of ASLE and affiliated organizations were started in the UK, Japan, Korea, New Zealand ( ASLEC-ANZ), India ( OSLE-India), Taiwan, Canada and Europe. Ecocriticism remembers the earth by rendering an account of the

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

116

indebtedness of culture to nature. The ecocritics try to revalue the more-than-human natural world, to which some texts and cultural traditions invite us to attend. Thus ecocriticism argues that defence of nature is vitally interconnected with the pursuit of social justice. Concerns of the Ecocritics One of the prime concerns of the ecocritics is to unearth the underlying cultural values. It endeavours to delve into the exact meaning of nature and examining the human perception of wilderness and so on and so forth. All ecocritics share an environmentalist motivation in one way or the other. The concerns of ecocriticism become glaringly explicit in the operational definition of Camilo Gornides, The field of enquiry that analyses and promotes works of art which raise moral questions about human interactions with nature, while also motivating audiences to live within a limit that will be binding over generations. (2006:16) Ecocriticism analyzes the role that the natural environment plays in the imagination of a cultural community at a specific historical moment, examining how the concept of nature is defined, what values are assigned to it or denied to it and why, and the way in which the relationship between humans and nature is envisioned. More specifically, it investigates how nature is used literally or metaphorically in certain literary or aesthetic genres and tropes, and what assumptions about nature underlie genres that may not address this topic directly. This analysis in turn allows ecocriticism to assess how certain historically conditioned concepts of nature and the natural, and particularly literary and artistic constructions of it, have come to shape current perceptions of the environment. In addition, some ecocritics understand their intellectual work as a direct intervention in current social, political, and economic debates surrounding environmental pollution and preservation. Green Literary Criticism, therefore, is confronted from the start with a spectrum of different and not always compatible approaches to the environment. Four different approaches are mentioned in Greg Garrards Ecocriticism: (I) The discursive construction foregrounds the extent to which the very distinction

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

117

of nature and culture is itself dependent on specific cultural values; (II) The aesthetic construction places value on nature for its beauty, complexity, or wildness; (III) The political construction emphasizes the power interests that inform any valuation or devaluation of nature; and finally; and (IV) The scientific construction, aims at the description of the functioning of natural systems. (2004:89) Any specific ecocritical analysis has to situate itself in relation to these various discourses and to critically interrogate their contribution to ecological projects. One of the central questions that necessarily emerge in such an interrogation is the question of how the value of the natural environment can and should be assessed in relation to human needs and goals. Social ecology generally insists that it is ultimately human needs and societal well-being which must determine our approach to nature, whereas deep ecology emphasizes on the contrary that nature has value in and of itself, independently of its functions for human society (this opposition has been discussed by Michael Bennett in American Book Reviews recent Urban Culture issue). The goals and methods of an ecocritical project will be crucially determined by how it defines itself in relation to these broader divisions within environmental thought. Ecocritical approaches confront the conflict between sciences claim that it delivers descriptions of nature that are essentially value-neutral, and the tendency of cultural analysis to see research as framed by specific ideological, political, and economic interests that do provide it with a set of more or less explicit values. But if the context out of which scientific research emerges is shaped by certain values, it does not necessarily follow that the results of this research will lend support to these values, a distinction that few cultural analyses of science bother to make. Due to its epistemological power as well as its pervasive cultural influence in the West and, increasingly other parts of the world, the scientific description of nature should be one of the cornerstones of ecocriticism, one that is usefully confronted and compared with literary visions of the environment. This confrontation enables not only an assessment of how scientific insight is culturally received

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

118

and transformed (rather than constructed), it also allows the critic to see where literature deviates or, in some cases, wishes or attempts to deviate from the scientific approach in view of particular aesthetic and ideological goals. The text thereby becomes a place where different visions of nature and varying images of science, each with their cultural and political implications, are played out, rather than simply a site of resistance against science and its claims to truth, or a construct in which science is called upon merely to confirm the inherent beauty of nature. Such an approach seems all the more opportune as some ecocritics have applied environmentalist terminology to literary texts in highly metaphorical ways: notions such as ecology, ecosystem, ecological balance, energy, resources, and scarcity have been transferred to texts conceived of as systems with an internal logic that, when activated by the reader, reveals the dynamic co-existence of diverse components and the texts overall evolutionary, negentropic thrust (for example, in William Rueckerts characterization of green plants as natures poets and poems as green plants among us). Such metaphoric translations of ecological vocabulary are highly problematic because they tend not only to revive the obsolete metaphor of the literary text as biological organism, but also to reintroduce, by way of nonliterary terminology, literary visions of nature as inherently creative, harmonious, and peaceful. Significantly enough, the concept of pollution is rarely translated in the same manner. In a time of intensifying ecological crises and increasing social conflict over the management and distribution of natural resources, as well as a growing number of engagements with environmental issues in literature and other art forms, literary criticism is only beginning to think through the implications of green thought for its own practices. Science, in one form or another, has formed a central part of ecological debates to date, and green criticism risks condemning itself to irrelevance if it ignores the contributions as well as the challenges that the scientific description of nature holds out to aesthetic articulations (2006:198). With a scientifically informed foregrounding of green issues in literature, ecocriticism

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

119

is likely not only to contribute significantly to the interdisciplinary dialogue between literature and science, but also to the broad rethinking of the relations between humans and nature that is currently taking place in societies across the globe. II William Wordsworth, the illustrious Poet of Nature belonging to the first generation of the romantics, advocated for preservation of nature for durable peace in and preservation of society. It is apt to say that Wordsworth, the great philosopher realized the hazards of destroying nature through human cruelty way back in the 18th century and hence warned mankind against the dangers they are facing today. It is wrong to dismiss Wordsworths pantheism as a theory merely attributing some spiritual significance to his approach to Nature. His pantheism spreads wings far beyond spiritual aspects and extends up to modern mans desperate quest of happiness and peace at the cost of nature and its assets. Wordsworth glorifies all objects of Nature; but he is concerned far less with the sensuous manifestations that fascinates majority of the poets of Nature, than with the spiritual that he finds underlying these manifestations. The divinization of Nature which began in the modern world during the renaissance and proceeded during the 18th century culminates for English literature in Wordsworth. Arthur Compton-Rickett comments, It was Wordsworths aim as a poet to seek for beauty in meadow, woodland, and the mountain top, and to interpret this beauty in spiritual terms (1999: 308). His divinization implies his respect for Nature; and such reverential attitude to Nature goes a long way to the conservation and protection of all objects of Nature. He is distinct from John Keats in that Keats delights in pagan joys in landscape, waterscape, and cloudscape with a tendency like P. B. Shelley to intellectualize Nature (1999: 307). Keats and Shelley are concerned less to marvel at Natures beauty than to exult at its inner significance which stand a chance to save Nature from destruction. With Wordsworth, Nature is both law and impulse but with Shelley, it is only impulse. Thus Wordsworths concept of Nature has something that induces in man a feeling for Nature which makes him ponder over and respect it.

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

120

The growth and development of Wordsworths love for Nature is brilliantly depicted in Tintern Abbey. Every stage of is an expose of his preoccupation with Nature and the need to take its care. As a child Wordsworth believed Nature to be a source of and scene for animal pleasure which he calls glad animal movements. Nature gives pleasure to an immature mind and hence, for the right development of a childs mind and thought, preservation of Nature is important. Pollution free Nature promotes a healthy mind in a child. He further says:

But secondary to my own pursuits And animal activities, and all Their trivial pleasures (2004: 51).

The trivial pleasures in the second stage developed into passion for the sensuous beauty of Nature. The sensuous charm of Nature could be felt and enjoyed only when Nature is allowed to grow in its beauty. Destruction of and harm to Nature divests it of its appeal and the sensuous beauty is lost. Referring to the boyish pleasures of this period when he viewed Nature with a purely physical passion, Wordsworth says in the Prelude:

The props of my affections were removed, And yet the building stood, as it sustained By its own spirit! All that I behold Was dear, and hence to finer influxes The mind lay open to a more exact And close communion (Ibid: 71).

At this stage whatever he saw gave him immeasurable pleasure. The same feeling has been painted in Tintern Abbey:

.The sounding cataract Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock, The mountain and the deep and gloomy wood Their colours and their forms, were then to me An appetite; a feeling and a love ( Ibid:52).

Such aching joys and dizzy raptures paved way for his irresistible tendency to link love of Nature with the love of man. Love of Nature develops a caring attitude in men which is essential for the preservation of Nature. Wordsworth always tried to instill in men a feeling that everything in Nature is a manifestation of God, and

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

121

therefore, harming Nature amounts to harming God. This fear in men would go a long way to save and protect Nature. The French Revolution and the resultant sufferings of people opened his eyes and now he could hear in Nature:

The still, sad music of humanity, Nor harsh, nor grating, though of ample power To chasten and subdue. (Ibid: 52)

Thus, Wordsworths love for nature developed and enabled him to see the manifestation of God in every object of Nature. He came to realize that there is a spirit in the woods which is a divine principle reigning in the heart of Nature. Warwick James says, At this stage, the fountain of Wordsworths entire existence was his mode of seeing God in Nature and Nature in God. (2002: 97) This is known as the period of Pantheism in Wordsworths life. This conviction of the poet that an Eternal Spirit pervades all the objects of Nature is brilliantly expressed in Tintern Abbey:

And I have felt A presence that disturbs me with the joy Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime Of something far more deeply interfused, Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns And the round ocean and the living air, And the blue sky and in the mind of man: (2004: 53)

Wordsworth firmly believes in the presence of a Spirit which gives him the joy of elevated thoughts and bows his head in respect to this divine power. He feels that Nature has a healing capacity and it is the panacea for all ailments; therefore human beings should live in tune with Nature without indiscriminate destruction of its objects. He bewails the cruelty of man to Nature in The World is Too Much with Us which elaborates the theme of modern mans indulgence in getting and spending resulting in their lack of concern for Nature. Materialistic attitude of men makes them oblivious of the fact that Nature should be protected. The beauty, charm and healing attributes of Nature demand that it should be preserved. He bewails men falling out of tune with Nature in the lines:

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon; The winds that will be howling at all hours,

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

122

And are upgathered now like Sleeping flowers; For this, for everything, we are out of tune; It moves us not. (2004:30)

Nature, according to Wordsworth is a living entity, and its preservation is mans responsibility and duty. Modern man falls out of tune and he fails to appreciate the beauteous aspects of nature because he is not living in harmony with Nature. Wordsworth feels frustrated when he sees destructive activities of man directed towards nature. His feeling for nature and its pitiable state makes him cry out, Little we see in Nature that is ours. (2004:30). His dissatisfaction over mans indiscriminate assault on Nature makes him say:

I would rather be A pagan suckled in a creed outworn; ( Ibidem)

Wordsworths conviction is that the pagans had greater respect for Nature than the modern men. He desires to be a pagan and thus shape and renew his reverential attitude to Nature. A.C. Compton Rickett says:

Apart from the sanctifying touch of Nature, men and women are poor creatures to Wordsworth. The farther we travel from Nature, the more paltry we become. This is the burden of his splendid sonnet The World is Too Much with Us. Better, he says in effect, people, the woods and streams, the plains and oceans, with nymphs and gods and goddesses, and retain something of the fresh simplicity and austere endurance of Nature, than give up our souls to the mere accumulation of wealth and to the superficial life of pleasure (1999: 311).

Preservation of Nature becomes all the more important because it keeps human beings pure and enhances their moral, ethical and spiritual prowess. Respect to Nature dissuades people from polluting and destroying it. Thus, Wordsworths concern for nature in the 18th century can be considered one of the first few attempts from littrateurs to attract the attention of mankind towards the endangered ecosystem. It is the inhabitants of the society whose initiatives can reduce the dangers of a collapsed ecosystem and

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

Journal of Literature, Culture and Media Studies

123

that is why the conservation has been a major concern for the intellectual circles around the world. Ecocriticism today, analyses the causes of the environmental degradation with a view to reawaken man towards his responsibility to Nature and the ecosystem. REFERENCES

Barry, Peter. 2009. Ecocriticism. Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary Theory. Manchester: Manchester UP. Buell, Lawrence. 1995. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. England: Harvard University Press. Compton-Rickett, Arthur. 1999. A History of English Literature. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd. Coupe, Lawrence, (ed.). 1991. The Green Studies Reader: From Romanticism to Ecocriticism. London:Routledge. Estok, Simon C. 2001. A Report Card on Ecocriticism. Ecocriticism: An Analysis of Home and Power in King Lear. AUMLA, 96. _ _ _. 2005. Shakespeare and Ecocriticism: An Analysis of 'Home' and 'Power' in King Lear.AUMLA 103. May. Gomides, Camilo. 2006. Putting New Definition of Ecocriticism to the Test: the Case of the Burning Season, a film (mal) Adaptation. ISLE, 13 (1). Glotfelty, Cheryll and Harold Fromm. (eds.). 1996. The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Athens and London:University of Georgia. Williams, Raymond. 1973. The Country and the City. London: Chatto and Windus. Vogel, Joseph Henry. 2008. Ecocriticism as an Economic School of Thought: Woody Allen's Match Point as Exemplary. OMETECA: Science and Humanities.

Assistant Professor, Department of English, Baptist College, Kohima. Professor, Department of English, Nagaland Central University, Kohima Campus.

Vol. IV 7&8 Jan. - Dec. 2012

You might also like

- Ecocriticism - Diff SourcesDocument176 pagesEcocriticism - Diff Sourceshashemdoaa0% (1)

- EcoDocument4 pagesEcoshivothamanNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism Is The Study of Literature and The Environment From An Interdisciplinary Point of ViewDocument5 pagesEcocriticism Is The Study of Literature and The Environment From An Interdisciplinary Point of ViewSantosh DevdheNo ratings yet

- AttachmentDocument9 pagesAttachmentMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- Cheryll Glotfelty: 'Chapter - IiDocument53 pagesCheryll Glotfelty: 'Chapter - IiYogesh AnvekarNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism - WikipediaDocument27 pagesEcocriticism - WikipediaRoha MalikNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism: An Essay: The Ecocriticism Reader Harold Fromm Lawrence BuellDocument10 pagesEcocriticism: An Essay: The Ecocriticism Reader Harold Fromm Lawrence BuellMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- Ecocritical Analysis of Rudyard Kipling's Selected PoemsDocument39 pagesEcocritical Analysis of Rudyard Kipling's Selected PoemsShah Faisal100% (1)

- EcocriticismDocument9 pagesEcocriticismharshidha K HNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism: Literature Going GreenDocument31 pagesEcocriticism: Literature Going GreenMonica Emad Hakeem SharkawyNo ratings yet

- 6 Ecocriticism (ENGL 4620)Document26 pages6 Ecocriticism (ENGL 4620)AnonenNo ratings yet

- PancatantraDocument10 pagesPancatantraSonu PanditNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism EssayDocument7 pagesEcocriticism EssayshumayounNo ratings yet

- SlovicThe-Fourth-Wave-of-Ecocriticism.docDocument6 pagesSlovicThe-Fourth-Wave-of-Ecocriticism.docFiNo ratings yet

- 24IJELS 108202052 AmericanDocument5 pages24IJELS 108202052 AmericanRafael MadejaNo ratings yet

- Environmentalism and EcocriticismDocument2 pagesEnvironmentalism and EcocriticismprabhuNo ratings yet

- Walep2006 06Document8 pagesWalep2006 06Maya MayasNo ratings yet

- (Wikipedia) EcocriticismDocument7 pages(Wikipedia) EcocriticismJuan Santiago Pineda RodriguezNo ratings yet

- EcocriticismDocument2 pagesEcocriticismAzzahra MaulidaNo ratings yet

- Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things From An Ecocritical ViewpointDocument8 pagesArundhati Roy's The God of Small Things From An Ecocritical ViewpointImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Ecosublime: Environmental Awe and Terror from New World to OddworldFrom EverandEcosublime: Environmental Awe and Terror from New World to OddworldNo ratings yet

- Timothy Morton - Ecology Without NatureDocument28 pagesTimothy Morton - Ecology Without NatureLuo LeixinNo ratings yet

- EcocriticismDocument10 pagesEcocriticismNazanin GhasemiNo ratings yet

- Admin, by The Name of NatureDocument7 pagesAdmin, by The Name of NatureIdriss BenkacemNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism Issue Volume 8, Number 1Document22 pagesEcocriticism Issue Volume 8, Number 1TamilaruviNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism (Literature Theory)Document2 pagesEcocriticism (Literature Theory)Lintang Gendis100% (3)

- Sarahfmacholdtfinalthesis 3Document31 pagesSarahfmacholdtfinalthesis 3api-341095033100% (1)

- A - Ecopedagogy Greeta PDFDocument14 pagesA - Ecopedagogy Greeta PDFTeresa SousaNo ratings yet

- (Timothy Morton) Ecology Without Nature PDFDocument260 pages(Timothy Morton) Ecology Without Nature PDFMohammedIlouafi100% (4)

- The Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism - Review-By-Rosemarie-RowleyDocument7 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism - Review-By-Rosemarie-RowleyNisrine YusufNo ratings yet

- Introduction: An Overview of EcocriticismDocument36 pagesIntroduction: An Overview of EcocriticismAnonymous EU3rMd4ZNo ratings yet

- Fadil's Chapter 2 ProposalDocument11 pagesFadil's Chapter 2 ProposalAdi FirdausiNo ratings yet

- Ecocritical Readings of Hughes, Heaney and ThomasDocument31 pagesEcocritical Readings of Hughes, Heaney and ThomasYogesh AnvekarNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism inDocument11 pagesEcocriticism insohamgaikwadNo ratings yet

- From: Greg Garrard, Ecocriticism. Routledge, 2004Document6 pagesFrom: Greg Garrard, Ecocriticism. Routledge, 2004Umut AlıntaşNo ratings yet

- Literature and EnvironmentDocument24 pagesLiterature and EnvironmentsohamgaikwadNo ratings yet

- Cheryll-Glotfelty (1)Document4 pagesCheryll-Glotfelty (1)rei.nahhh8No ratings yet

- Ecocriticism A Study of Environmental IsDocument3 pagesEcocriticism A Study of Environmental IsBlack LotusNo ratings yet

- Ursula Heise - Hitchhicker's Guide To Eco CriticismDocument14 pagesUrsula Heise - Hitchhicker's Guide To Eco CriticismgwenolaNo ratings yet

- The Works of Rabindranath Tagore An Ecocritical ReadingDocument9 pagesThe Works of Rabindranath Tagore An Ecocritical ReadingEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Eco CriticismDocument3 pagesEco CriticismImenBoughanmiNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism 1Document6 pagesEcocriticism 1Black LotusNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism in Turkey Explores Unique ApproachesDocument18 pagesEcocriticism in Turkey Explores Unique ApproachesPallabi DeoghuriaNo ratings yet

- The Problems and Challenges of EcocriticismDocument9 pagesThe Problems and Challenges of EcocriticismHind AlemNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism (Mid)Document2 pagesEcocriticism (Mid)Saif Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- A Guide To EcocriticismDocument14 pagesA Guide To EcocriticismAlton Melvar Madrid Dapanas100% (1)

- New, "Life, Uh, Finds A Way"Document17 pagesNew, "Life, Uh, Finds A Way"Paul WorleyNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism Sample Research ResultsDocument1 pageEcocriticism Sample Research ResultsAnonymous FHCJucNo ratings yet

- MohammadAtaullahNuri Article2 PDFDocument16 pagesMohammadAtaullahNuri Article2 PDFSensai KamakshiNo ratings yet

- Timothy Morton Ecology Without Nature Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics TheoryleaksDocument262 pagesTimothy Morton Ecology Without Nature Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics TheoryleaksAmado Jazael Peña Broissin100% (1)

- Reinventing Nature?: Responses To Postmodern DeconstructionFrom EverandReinventing Nature?: Responses To Postmodern DeconstructionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- These "Thin Partitions": Bridging the Growing Divide between Cultural Anthropology and ArchaeologyFrom EverandThese "Thin Partitions": Bridging the Growing Divide between Cultural Anthropology and ArchaeologyNo ratings yet

- On Ecological Philosophy in WaldenDocument6 pagesOn Ecological Philosophy in WaldenIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism DefinitionDocument2 pagesEcocriticism DefinitionJoséGuimarãesNo ratings yet

- A Reading of Elemental Ecocriticism in Select Northeast Indian English PoetryFrom EverandA Reading of Elemental Ecocriticism in Select Northeast Indian English PoetryNo ratings yet

- EcologyWithoutNature Morton PDFDocument15 pagesEcologyWithoutNature Morton PDFdcorralesNo ratings yet

- Assignment MoDocument1 pageAssignment Moمحمد صلاحNo ratings yet

- EcocritismDocument43 pagesEcocritismMehtap Özer Isovic100% (1)

- Toxic DiscourseDocument27 pagesToxic Discoursermrdk9No ratings yet

- A Brief History of EcocriticismDocument8 pagesA Brief History of EcocriticismSantosh Devdhe100% (1)

- Guidelines For Thesis and Dissertation FormatingDocument22 pagesGuidelines For Thesis and Dissertation Formatingjavaire.heNo ratings yet

- ExpressIssue4 2013Document24 pagesExpressIssue4 2013Cathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- SPRD SpreadDocument2 pagesSPRD SpreadCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- eKPHRASIS & oBJECTHOODDocument245 pageseKPHRASIS & oBJECTHOODCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- 1 MergedDocument24 pages1 MergedCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- 007e07 03 14Document1 page007e07 03 14Cathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Booklist DisabilitiesDocument13 pagesBooklist DisabilitiesCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Magic Realism as Post-Colonial DiscourseDocument16 pagesMagic Realism as Post-Colonial Discourseleonardo_2006100% (2)

- Brock Braithwaite Andrea 2003Document147 pagesBrock Braithwaite Andrea 2003Cathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Business Junior CertDocument9 pagesBusiness Junior CertCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- 09ENG ZhurbaDinaDocument37 pages09ENG ZhurbaDinaCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- USI Vision 2014Document6 pagesUSI Vision 2014Cathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Benjamin MyovelaDocument87 pagesBenjamin MyovelaCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- DINNER - SUN-WED 5.30-10PM, THURS-SAT 5.30-11PM StartersDocument1 pageDINNER - SUN-WED 5.30-10PM, THURS-SAT 5.30-11PM StartersCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Let Your Parents Take Up: The Irish TimesDocument1 pageLet Your Parents Take Up: The Irish TimesCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- 001UE2013 10 08 - MergedDocument12 pages001UE2013 10 08 - MergedCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- SpecialtysDocument6 pagesSpecialtysCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- SL000010 Tabloid 285 X 360 PDF Size SpecificationDocument3 pagesSL000010 Tabloid 285 X 360 PDF Size SpecificationCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- SoccerDocument2 pagesSoccerCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- ConfigDocument1 pageConfigCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- EcowDocument6 pagesEcowCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- MSIL File CatalogDocument254 pagesMSIL File CatalogCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- What Is Profit & Loss All AboutDocument17 pagesWhat Is Profit & Loss All AboutKenville JackNo ratings yet

- 08Document13 pages08Cathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Thesis-Dissertation Proposal Template (English)Document5 pagesThesis-Dissertation Proposal Template (English)Christina RossettiNo ratings yet

- Literary Theories: Critical Lenses for AnalysisDocument4 pagesLiterary Theories: Critical Lenses for AnalysisCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- LylustudiesDocument26 pagesLylustudiesCathal O' GaraNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire Construction PrinciplesDocument5 pagesQuestionnaire Construction PrinciplesAnonymous cmUt3RZij2No ratings yet

- 如何書寫被排除者的歷史:金士伯格論傅柯的瘋狂史研究Document53 pages如何書寫被排除者的歷史:金士伯格論傅柯的瘋狂史研究張邦彥No ratings yet

- Spring 2012Document16 pagesSpring 2012JoleteNo ratings yet

- (International Library of Technical and Vocational Education and Training) Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Auth.), Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Eds.) - Handbook of Technical and Vocational Educatio PDFDocument1,090 pages(International Library of Technical and Vocational Education and Training) Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Auth.), Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Eds.) - Handbook of Technical and Vocational Educatio PDFAulia YuanisahNo ratings yet

- Enrolment Action Plan Against COVID-19Document4 pagesEnrolment Action Plan Against COVID-19DaffodilAbukeNo ratings yet

- Teachers Resource Guide PDFDocument12 pagesTeachers Resource Guide PDFmadonnastack0% (1)

- Luck or Hard Work?Document3 pagesLuck or Hard Work?bey luNo ratings yet

- Movers Speaking Test OverviewDocument57 pagesMovers Speaking Test OverviewThu HợpNo ratings yet

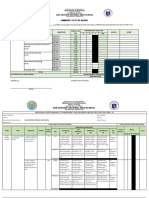

- IPCRF Form TeachersDocument9 pagesIPCRF Form TeachersrafaelaNo ratings yet

- The Cairo Declaration ABCDocument2 pagesThe Cairo Declaration ABCnors lagsNo ratings yet

- On The Integer Solutions of The Pell Equation: M.A.Gopalan, V.Sangeetha, Manju SomanathDocument3 pagesOn The Integer Solutions of The Pell Equation: M.A.Gopalan, V.Sangeetha, Manju SomanathinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Math Inquiry LessonDocument4 pagesMath Inquiry Lessonapi-409093587No ratings yet

- 2020-2021 Instructional Assistant ExpectationsDocument37 pages2020-2021 Instructional Assistant Expectationsapi-470333647No ratings yet

- Lab Report Template and Marking SchemeDocument1 pageLab Report Template and Marking Schememuzahir.ali.baloch2021No ratings yet

- Multiplication Tables From 1 To 50Document51 pagesMultiplication Tables From 1 To 50Sairaj RajputNo ratings yet

- Tie Preparation (Investigation & News)Document4 pagesTie Preparation (Investigation & News)Joanna GuoNo ratings yet

- Samuel Itman: Education Awards/CertificatesDocument1 pageSamuel Itman: Education Awards/Certificatesapi-396689399No ratings yet

- Fol Admissions 2021-22 FaqsDocument14 pagesFol Admissions 2021-22 FaqsYash RajNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Domains Taxonomy ChartDocument1 pageCognitive Domains Taxonomy ChartNorila Mat ZanNo ratings yet

- Barking Abbey Basketball AcademyDocument11 pagesBarking Abbey Basketball AcademyAbbeyBasketballNo ratings yet

- Xue Bin (Jason) Peng: Year 2, PHD in Computer ScienceDocument3 pagesXue Bin (Jason) Peng: Year 2, PHD in Computer Sciencelays cleoNo ratings yet

- DLP Communicable DiseasesDocument10 pagesDLP Communicable DiseasesPlacida Mequiabas National High SchoolNo ratings yet

- SPED 425-001: Educational Achievement Report Towson University Leah Gruber Dr. Fewster 4/30/15Document12 pagesSPED 425-001: Educational Achievement Report Towson University Leah Gruber Dr. Fewster 4/30/15api-297261081No ratings yet

- Samples English Lessons Through LiteratureDocument233 pagesSamples English Lessons Through LiteratureEmil Kosztelnik100% (1)

- 8th Merit List DPTDocument6 pages8th Merit List DPTSaleem KhanNo ratings yet

- Speak OutDocument44 pagesSpeak OutJackie MurtaghNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Men Qualification NTU PumpfestDocument1 pageIntermediate Men Qualification NTU PumpfestYesenia MerrillNo ratings yet

- catch-up-friday-plan-mapeh-8Document6 pagescatch-up-friday-plan-mapeh-8kim-kim limNo ratings yet

- Technical and Business WritingDocument3 pagesTechnical and Business WritingMuhammad FaisalNo ratings yet

- UCL Intro to Egyptian & Near Eastern ArchaeologyDocument47 pagesUCL Intro to Egyptian & Near Eastern ArchaeologyJools Galloway100% (1)