Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brumfiel BreakingEnteringEcosystem

Uploaded by

Charlie HigginsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brumfiel BreakingEnteringEcosystem

Uploaded by

Charlie HigginsCopyright:

Available Formats

ELIZABETH M.

BRUMFIEL Albion College

Distinguished Lecture in Archeology: Breaking and Entering the Ecosystem-Gender, Class, and Faction Steal the Show

This article was presented as the third annual Distinguished Lecture in Archeology at the 90th annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, November 22, 1991, in Chicago, Illinois.

American archeology has been operating under the assumptions of the ecosystem approach. The longevity of this approach is no accident; the ecosystem program has been highly productive. From ecosystem theory, we have acquired a sensitivity to structural causation and an appreciation for the interconnectedness of social and ecological variables. We have also gathered much relevant information about energy exchanges, information flows, scheduling, risk, nutrition, labor intensification, and demographic trends in prehistory. But while the ecosystem approach has been very productive in some areas of research, it has retarded progress in others, particularly in the analysis of social change. The analysis of social change has been hampered by ecosystem theorys insistence upon whole populations and whole behavioral systems as the units of analysis. In focusing on whole populations, and whole systems of adaptive cultural behavior, ecosystem theorists have neglected the dynamics of social change arising from internal social negotiation. Social negotiation consists of conflicts and compromises among people with different problems and possibilities by virtue of their membership in different alliance networks. Most frequently, these alliance networks arise on the basis ofgender, class, and factional affiliation. This paper argues three points. First, the ecosystem theorists emphasis upon whole populations and whole adaptive behavioral systems obscures the visibility of gender, class, and faction in the prehistoric past. Second, an analysis that takes account ofgender, class, and faction can explain many aspects of the prehistoric record that the ecosystem perspective cannot explain. Third, an appreciation for the importance of gender, class, and faction in prehistory compels us to reject the ecosystem-theory view that cultures are adaptive systems. Instead, we must recognize that culturally based behavioral systems are the composite outcomes of negotiation between positioned social agents pursuing their goals under both ecological and social constraints.

OR ALMOST THIRTY YEARS,

The Ecosystem Approach

The ecosystem approach rests upon two basic tenets. First, ecosystem theorists propose that human populations adapt to their environments through culture-based behavioral systems. Our role as archeologists is to record stability and change in these behavioral systems over time and to explain this record as a product of population-environment interaction (Steward 1955:36-42; White 1959:56; Binford 1962:218; Flannery 1967:121;

ELIZABETH M . BRUMFIEL is Profcssor, Department o f Anthropology and Sociology, Albion College, Albion, MI 49224.

551

552

AMERICAN

ANTHROPOLOGIST

[94, 1992

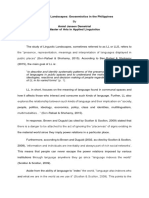

Sanders and Price 1968:71; Hill 1977:88; Redman 1978a:13; Struever and Holton 1979:84-85). Second, ecosystem theorists assert that humans play a very limited role in determining the course of culture change. Applying the model of natural selection to cultural systems, ecosystem theorists argue that human decisions, intentions, and creativity are simply sources of behavioral variation. Systemic context determines the differential survival of these behaviors. Behavioral changes that produce viable cultural systems endure and leave their imprint on prehistory; behavioral changes resulting in nonviable cultural systems disappear as the cultures, themselves, fail (White 1949:141; Flannery 1967:122, 1972:411; Sanders and Price 1968:73; Hill 1977:66-67; Redman 1978a:10-13; Dunnell 1980:62; Braun and Plog 1982:506; Price 1982:724). Together, these two propositions focus attention on the cultural-behavioral system rather than the social actor. This focus is clearly evident in that diagnostic artifact of ecosystem archeology, the flowchart of culture change (see Figure 1; other examples include Wright 1970, 1977; Flannery 1972; Harris 1977; Johnson 1978; King 1978; and Hassan 1981). For example, the emphasis on systems rather than social actors determines the perspective of the flowchart, which is "etic" rather than "emic." That is, the chart provides an overview of the system as a whole, rather than a view of the system as it might look to a member of the society. As Cowgill (1975:506) notes, ecosystem theorists have no real interest in "the needs, problems, possibilities, incentives, information, and viewpoints of specific individuals or categories of individuals" within the system. The emphasis on systems rather than social actors also determines the units that constitute the boxes or components in this flowchart, which are activities rather than agents, functions rather than performers. Social actors are reduced to invisible, equivalent, abstract units of labor power. Finally, the ecosystem theorists' reliance upon natural selection as the mechanism

Roduslive

Increasing D i r u a c r between Admnliiitraors and Popdotior

I"

h g s

Figure I Positive feedback interrelationships among cultural and environmental variables leading to the increasing importance and stratification of class structure in Mesopotamian society (afterRedman 1978b:333).

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

553

of systemic change determines the nature of the connections between systemic components. The connections between boxes are either functional responses to population needs (for example, specialized food production requires the redistribution of foodstuffs) or necessary consequences of one variable for another (for example, the intensification of agriculture necessarily entails the differentiation in wealth). These connections are stimulus-response or input-output relationships. The motivations, decisions, and actions that actually link variables are not diagramed, so that a small black box intervenes between each pair of linked components (Clarke 1968:58-62; McGuire 1983:92). This chart is clearly concerned with system-level evolutionary consequences and not the processes of social change. The ecosystem focus on the cultural-behavioral system has several drawbacks. First, it makes invisible the past activities and contributions of particular sets of social actors, for example, women, peasants, and particular racial or ethnic groups. When archeologists fail to assign specific activities to these groups, dominant groups in contemporary society are free to depict them in any way they please. Most often, dominant groups will overstate the historical importance of their own group and undervalue the contributions of others, legitimating current inequalities (Williams 1989; Patterson 1991a). In addition, when women, peasants, and ethnic groups are assigned no specific activities in the past, professional archeologists make implicit assumptions about their roles and capabilities, resulting in the widespread acceptance of untested, and possibly erroneous, interpretations of archeological data (Conkey and Spector 1984; Nelson 1990). As archeologists, we have a professional responsibility to present our prehistories in ways that make distorted appropriations of the past as difficult as possible, and, as scientists, we need to work with models that expose our implicit assumptions concerning human roles and capabilities to critical reflection and hypothesis testing. The systemic models of ecosystem theory hinder both these efforts. Second, the ecosystem focus on the cultural-behavioral system leads us to seriously underestimate the difficulties of systemic change. All institutional innovation has personnel and energy requirements (DAltroy and Earle 1985), and if these requirements cannot be met, the institution, no matter how beneficial, will not come into being. But, in human society, access to labor and resources is defined by social categories, and this allocation is maintained not by cultural norms, which are frequently flouted by actors pursuing their particular goals, but by alliance networks that orgariize coercive force. Typically, such alliance networks materialize on the basis of gender, class, and faction. A major task in understanding systemic change is to understand how realignments in these alliance networks are brought off, permitting a redefinition of social categories and a reallocation of resources and personnel (see Eisenstadt 1963). But ecosystem theory focuses on abstract behavior rather than the groups of actors that control resources and power. This focus obscures both the processes and possibilities of systemic change. Finally, the ecosystem focus on the cultural-behavioral system leads us to overestimate the external as opposed to the internal causes of change. As Adams ( 1978:329-330) observes, Much of the flux and dynamism of the historic record derives from the periodic convergence and divergence of the partly disarticulated geographic, ethnic, class, kin, and other components of human society. Cause-effect regularities may exist because of the logic of social negotiation instead of the logic of adaptive response. Rather than regarding prehistory as a long-term, systemic-level process of adaptation to environmental change, it may be better to see prehistory as a string of short-term, composite outcomes of social conflict and compromise among people with different problems and possibilities by virtue of their membership in differing alliance networks. Archeology has much to gain from focusing on the organization of actors rather than behavioral systems, especially groupings of actors defined on the basis of gender, class, and factional affiliation.

(6

554

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

194, 1992

Gender

In the focus on behavioral systems rather than actors, gender disappears. Despite the widespread recognition that age and sex provide universal bases of social status and the division of labor in human societies, gender (and age) have received very little attention from archeologists. Flowcharts of social process, such as that cited above, never assign gender to the activities they diagram. The lack of attention to gender has continued through the 1980s, even in archeological studies of the household, where production, distribution, transmission, and reproduction are based in very direct and concrete ways on a gendered division of labor and a gender-based definition of social status (Tringham 1991:lOl; for examples, see Wilk and Rathje 1982; Wilk and Ashmore 1988; Stanish 1989). Even when analysis involves the definition of probable male and female activities and activity areas (e.g., Clarke 1972; Flannery and Winter 1976), it stops short of reconstructing integrated male and female roles. This failure to define gender roles is an understandable consequence of the emphasis on behavioral systems. The unstated attitude is, I think, that it really doesnt matter who did what in prehistory, as long as the necessary subsistence functions were performed. This is thought to be especially true of household subsistence tasks, since the household is regarded as a cooperative unit based on the pooling of goods and services. But it matters very much who did what, for at least three reasons. First, when gender roles are not explicitly defined, they are implicitly assumed (Conkey and Spector 1984; Conkey and Gero 1991). It has been taken for granted that men, or men and women, procure food while women process it. Men conduct trade and warfare; women engage in household maintenance. Men make states; women make babies, or so it is assumed. And assigning a task to women has virtually assured that variability in the archeological data pertaining to that task would go unrecognized and unexplained. Compare, for example, the extensive analysis of food procurement using sophisticated models such as optimal foraging theory and game theory with the perfunctory attention given food processing. There is a greater literature on the heat treatment of chert than on the heat treatment of food (but see Stahl 1989). Studies of ceramic production far outnumber studies of ceramic use. Spatial and temporal variability in nutting stones, grinding stones, cooking vessels, fuels, hearths, and ovens has not been adequately studied (but see Jackson 1991; Bartlett 1933; Clark 1988; Braun 1981; Costin 1986; Brumfiel 1991; Hastorf and Johannessen 1991; Hayden 1981). The same has been true for tools and facilities associated with hide-working, textile production, and the manufacture of cord and cord products such as traps and nets (but see Weiner and Schneider 1989; Kehoe 1990). I believe that the explicit effort to assign activities to female or male actors might make some of these disparities obvious and stimulate ground-breaking research into these littleknown classes of archeological data, delineating both their range of variability and the strategic factors that explain their variation. Second, assigning activities to male or female actors is a first step in constructing integrated models of the gendered division of labor. Such models provide a baseline for estimating work loads and pinpointing scheduling conflicts, both of which have important implications for strategic decision making and behavioral change (Claassen 1991277). Flannery (1968a:75) pointed out some time ago that the division oflabor along the lines of sex is one common solution to scheduling conflicts in subsistence strategies. But only recently has it been suggested that scheduling problems in womens subsistence activities might explain observed changes in the exploitation of some resources, such as shellfish and plants, including plant domestication (Claassen 1991; Watson and Kennedy 1991), or that maximizing the efficiency of womens work routines may be the decisive factor in structuring some settlement patterns (Jackson 1991). Third, the calculation of gender-specific work loads has important implications for modeling systemic change. For example, most models of emerging nonegalitarian relations assume the ability to generate surplus production, a fund of power (Sahlins

Brurnfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

555

1968:89; DAltroy and Earle 1985), either to use in adaptively advantageous activities such as banking and redistribution (Flannery 1968b; Halstead and OShea 1982), or to incur the social indebtedness of followers (Rowlands 1980; Kristiansen 1981; Brumfiel and Earle 1987; Clark and Blake 1993), or to sponsor feasts that enable would-be leaders to claim to be intermediaries between the living and their sacred ancestors (Friedman 1973). Because the vast majority of production in agrarian societies is household-based, political change almost always involves the restructuring of household labor. The initial stages of social inequality ought to be marked by high birthrates, polygamy, and/or the inception of dependent labor within the households of would-be leaders (Chevillard and Leconte 1986; Coontz and Henderson 1986). As inequality increases and goods and labor are extracted from a widening circle of clients and subjects, a growing proportion of households will experience changes in composition and organization. But whatever specific changes occur in household labor, they will always be a function of the existing time/ energy budgets of household members as established by the gendered division of labor. For example, among the historic Blackfoot, women were responsible for hide-working. When the markets for tanned robes expanded during the 19th century, polygamy provided an obvious avenue of advance for wealthy, ambitious men. According to Lewis ( 1942:38-40), polygamy did expand, accompanied by increased social inequality among men and increased oppression of women who were taken as third or additional wives. Had the division of labor made male rather than female labor the key to obtaining European goods, then would-be leaders would have had to resort to other strategies of labor mobilization and surplus accumulation. Thus, to explain strategies of accumulation, and to understand their limits, archeologists must examine the gender-specific organization of household labor. In studying the organization of household labor, archeologists may note changes that placed household members in opposition to one another. For example, Hastorf (1991) presents botanical evidence from the Mantaro Valley, Peru, that suggests that maize beer production intensified under Inca rule. In the Andes, maize beer production is traditionally a womans task. At the same time, skeletal evidence indicates that under Inca rule women consumed less maize beer than did men. One would have to ask, how did it come to be that women produced more beer and yet consumed a smaller proportion of what they produced? Did this arrangement somehow maximize the joint benefits of the collective household economy? Or does it indicate the flow of benefits from female to male household members? If so, how was this flow of benefits achieved? Similarly, we could look back to the previous example and ask, what alterations of situation or allegiance permitted the institution of a less egalitarian marriage relationship for third and subsequent Blackfoot wives? Rather than attributing change to a heavy-handed selection process, we must acknowledge the extent to which a cultural system is an outcome of active negotiations between individuals with differential power, both within the household (Hartmann 1981; Moore 1990) and beyond (Wolf 1982:385-391). To explore this issue more fully, let us consider the way in which ecosystem theorists have dealt with the relationship between classes in prehistoric societies.

Class

There is an interesting asymmetry in the way that ecosystem theorists have treated dominant and subordinate classes, as is evident in our flowchart example (see Figure 1). Elites constitute the only people-filled component of the system, and they are a very active component-there are a lot of arrows leaving this box as well as entering it.* In contrast, the activities and interqts of subordinate classes are divided among various systemic components and are nowhere regarded as a coherent force in determining ecosystem structure. The existence of this asymmetry is a straightforward consequence of the assumptions of ecosystem theory. Elites are viewed as performing managerial functions and, therefore, as being endowed with the ability to impose their decisions upon the social

556

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[94, 1992

system. Managerial theories postulate no similar role for subordinate classes, and therefore do not grant them any similar power to influence the system. In ecosystems theory, only the emergence of the elites requires explanation; subsistence producers have always been with u s 3 But the emergence of elites does not leave non-elites untransformed. The development of control at the apex of the systemic hierarchy implies the development of subordination at lower levels, regardless of whether this subordination is considered beneficial systemserving regulation or pathological self-serving exploitation (Flannery 1972). And many systemic relationships within emerging states are revealed only when subordinate classes enter the model as people coping with the unfamiliar circumstances of subordination rather than as abstract performers of disaggregated systemic processes. For example, if commoners or peasants appeared in the flowchart diagrams, we would be more likely to ask two key questions about the process of state formation. First, what impact did emerging hierarchy have on the lives of people in subordinate groups? And second, to what extend did commoner response to state formation determine the structure of hierarchy? These questions enable us to account for certain aspects of the archeological record that the ecosystem approach leaves unexplained. The first of these questions has seemed nonproblematic to most ecosystem theorists, who assume that, under conditions of emerging hierarchy, commoners simply maintained their homeostatic exchanges with the environment under more stable, better-managed conditions (but see Gall and Saxe 1977). But as we have observed, the emergence of hierarchy always involves the transfer of goods from the hands of direct producers to political elites with profound implications for other aspects of the cultural system. For example, during the last four centuries of the pre-Hispanic era, coinciding with the emergence of a regional state in the Basin of Mexico, the Basin experienced a surge of demographic growth, which produced an eightfold increase in population (Sanders, Parsons, and Santley 1979:184-186). Earlier periods of modest or even negative growth in the Basins population suggest that there was nothing natural about this dramatic growth (see Blanton 1975; Cowgill 1975). The absence of evidence for drastic changes in the Basin of Mexico environment or its food-producing technology leaves this growth quite unexplained within an ecosystem framework. However, if we consider the impact of emerging hierarchy on the lives of subordinate groups, we might suggest that it was the conditions of state formation, itself, that led to population growth (reversing the usual ecosystem proposition that population growth causes state formation). Either because the states demand for tribute, levied on a household basis, increased the need for household labor, or because the increasing levels of violence made less certain the survival of children to support parents in their old age, households brought into expanding states may have desired and produced more children. This and other transformations of the household, especially gender and kinship relations, under conditions of state formation are problems requiring much further investigation (see Rapp 1978; Gailey 1985a, 1985b, 1987; Silverblatt 1987, 1988). Turning to the second question, the extent to which commoner response determined the structure of emerging hierarchy, ecosystem theorists have usually assumed that the managerial benefits conferred by hierarchy would make subordinate groups willing participants in the system. However, this leaves unexplained forms of activity that appear to be efforts by dominant classes to work around subordinate classes to avoid provoking their hostility. For example, early stages of state formation are often characterized by the development of private estates, controlled by elite individuals or corporations, and staffed by some sort of unfree labor, such as slaves, war captives, or clients. Examples include the palace and temple estates of Mesopotamia (Fox and Zagarell 1982; Zagarell 1986) and the slave villages in African kingdoms such as Gyaman and Wolof (Terray 1979; Tymowski 1991). Zagarell (Fox and Zagarell 1982; Zagarell 1986), Gailey ( 1985a), and Tymowski (1991) suggest that these enclave economies, rather than representing the power of the state, are symptoms of its weakness. Unable to supply sufficient benefits or

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

557

to muster sufficient coercion to collect taxes from a resident kin-ordered commoner class, elites were forced to establish their own income-generating enterprises using the labor of individuals who were separated from the protection of their kinship groups. Warfare is another means of financing hierarchy in the face of commoner resistance. The spoils of war may be used to increase the prestige of leaders by increasing their capacity for generosity (Santley 1980:142; Gilman 1981). And warfare may provide a mechanism for capturing resources for enclave economies. Both war captives (Gailey 1985a; Zagarell 1986; Tymowski 1991) and land (Webster 1975) seized in war lie outside the control of traditional kin groups. Such assets free leaders from dependence upon kinship status, kinship ties, and, ultimately, the kinship ethic. In enclave economies and economies based upon plunder, leaders and followers strike a bargain: intra-group exploitation is minimized so that leaders and followers can cooperate to dominate and exploit outsiders. The formation of such alliances or factions is a frequent means ofconstructing political power (Lenin 1939:102-108; Gilman 1981; Blaut 1987:176- 195).

Factions

When the adaptive value of sociopolitical institutions is assumed, no explicit analysis of power building is necessary. Ruling elites derive their power from the regulation and control of a complex subsistence economy, and they fall from power only when their selfinterested activities impede the efficient operation of the economy (Flannery 1972:414; Johnson 1978:104; Redman 1978b:343-344). Politics becomes a function of subsistence, and concern over political process disappears. This is reflected in the flowchart example (Figure l ) , where the subsistence economy receives much more attention than the political economy, and all administrative elites occupy a single, undifferentiated, box. However, if ecosystem theorists believe that power building in prehistoric complex societies can be ignored, they are in sharp disagreement with the leaders of these groups. In the complex societies known from ethnohistorical records, power building is a central concern. Much (if not all) of the administrative bureaucracy is devoted to maintaining power. Typically, early states contain military bureaucracies organizing coercive force, tax-collecting bureaucracies organizing surplus extraction, and functionaries in charge of administered trade, elite craft production, and religious ritual, all of which communicate ideologies of elite solidarity and dominance. Rulers invest heavily in power building because the threats to their survival are numerous (Kaufman 1988). Competing factions form around would-be usurpers within the highest-ranking nobility, would-be independent paramounts within the provincial nobility, and would-be conquerors among the leaders of neighboring groups. These groups threaten a ruler with coup, separatism, and conquest, respectively. Adding to the complexity of the situation, these groups frequently form alliances with each other and with outsiders. For example, usurpers and separatists may be aided by neighboring rulers who see ties ofpatronage as an alternative to conquest for expanding territorial control (Hicks 1993). Commoners frequently support usurpers or separatists to put an end to oppressive regimes (Fortes and Evans-Pritchard 1940:1 1 ; Fallers 1956:247; Gluckman 1956:42-45; Sahlins 1972:145-148; Helms 1979:28). Political competition is never fully resolved. Rulers always have siblings and offspring who conceive ambitions to rule (Goody 1966; Burling 1974). Regional hierarchies must always depend upon lower-level local hierarchies, and these local hierarchies will possess some organizational integrity and some ability to pursue autonomous goals (Webster 1976:818; Yoffee 1979:14). No matter how great the territory incorporated into the state, it always has borders beyond its control where refugees fleeing state expansion can fall in with peripheral leaders, usually the political clients and trade partners of the state, and together, refugees and leaders can threaten state control of frontier regions (Lattimore 1951; Bronson 1988; Barfield 1989; Patterson 1991b:107-116). Almost always, in trying to satisfy some of these factions, rulers alienate others.

558

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[94, 1992

Rulers, then, must concern themselves with the successful management of a political economy, that is, the distribution ofwealth to support the distribution of power, and vice versa. Some ecosystem theorists (e.g., White 1959; Price 1982:724) equate political economy with subsistence economy, regarding power as a simple function of energy. For example, Gall and Saxe (1977:264-265) state, When intersystem competition occurs . . . complex sociocultural systems persevere because success in the long run goes to the specialist who can harness the greatest number of kilocalories. But I would argue that successful power holders must be effective manipulators of both natural resources and social relations. Maintaining a following requires wealth, but it also requires a good sense of timing and an ideology that maintains the loyalty of followers. Several aspects of prehistoric economies are better understood when viewed as aspects of a political economy rather than a subsistence economy. As discussed above, the intensification of household production is often the result of the need for ever-larger quantities of surplus to finance factional competition (Bender 1978; Earle 1978; Hayden 1990; Brumfiel and Fox 1993). The elaboration of prestige goods and the construction of flamboyant civic/religious architecture, both of which commonly occur in the archeological record in situations of emerging complexity, play important roles in the construction of political alliances (Webster 1976; Yoffee 1979; Rowlands 1980; Kristiansen 1981; Earle 1987; Brumfiel 1987a, 1987b). The prevalence of factional competition in complex societies has important theoretical implications. It suggests that complex society is not the well-integrated adaptive system implied by the orderly flowcharts ofecosystem theorists. Rather, as Patterson (1992) proposes, it is a continually shifting patchwork of internally differentiated communities bound together by interacting contradictions and mediations. Paynter ( 1989:386) also comments on the absence of integration in complex societies: Tensions between cores and peripheries, civil and kin groups, rulers and ruled, merchants and lords, men and women, and producers and extractors evoke an unwieldy tangle of [interaction] processes. The intensity and diversity of these internal tensions mean that, over long periods of time, states are guided by short-term crisis management rather than long-term system-serving goals. This, in turn, calls into question the fundamental ecosystem-theory assumption that complex societies are adaptive. In biology, evolutionary success is measured by survival, and no single variable can predict evolutionary success. Not the amount of energy captured by the organism, nor the efficiency of energy capture, nor the quantity of biomass supported in the system ensures continued survival. If we reject all proxy measures of the evolutionary success of complex societies and apply instead the only valid measure, that is, persistence, then complex societies, which are often short-lived (Yoffee and Cowgill 1988; Paynter 1989:375; Patterson 1992), may have to be judged relatively unsuccessful organizational forms. The history of states is the history of strategy and counterstrategy deployed by oppositional groups, leading cumulatively to the emergence of social hierarchy and its dissolution. But the membership of these groups, their sources of strength, and the logic of their strategies cannot be discovered by systemic approaches that ignore the organization of human actors.

S ystems-Centered and Agent-Centered Perspectives

Finding the proper balance between the individual and the system, between agency and structure, has been a persistent problem for archeology. Under the sway of ecosystem theory during the 1960s and 1970s, whole populations and whole systems of adaptive cultural behavior served as the units of analysis. During the 1980s, a series of actor-based decision-making models have been introduced to archeology (Keene 1979; Winterhalder and Smith 1981; Boyd and Richerson 1985; Braun 1990; Durham 1990; Earle 1991; Shennan 1991). T o the extent that these models contextualize decision making in a structure of ecologically and socially determined payoffs, they show considerable promise. But

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

559

many of these models have inherited processual archeologys insensitivity to gender, class, and factional affiliation; thus, they fail to inquire how payoffs, and thus decisions, vary by social category. To strike a proper balance between agency and structure, we will have to accept the following principles. First, we must reject the notion that a cultural system is a homeostatic, living system subject to selection and adaptive change. Instead, we should recognize that cultural systems are contingent and negotiated, the composite outcome of strategy, counterstrategy, and the unforeseen consequences of human action. Second, following suggestions by Cowgill (1975), Orlove (1980), Kohl (1981), and Blanton et al. (1981:23-24), we should recognize that human actors, and not reified systems, are the agents of culture change. Human actors devise complex strategies to solve their problems and meet their goals, and these strategies are neither random nor shaped solely by differential survival either at the population level as ecosystem theorists would have it, or at the level of the individual as more recent evolutionary culture theorists claim. This is not to say that humans always get it right or that their actions do not lead to unforeseen consequences. It is simply to argue that human goals are relevant to cultural outcomes. Third, we should recognize that to argue that human action is goal-directed is not necessarily to open the floodgates to cultural particularism. For, as ecosystem theory has taught us, human action occurs within a structural context that shapes both its goals and outcomes. Goals are achieved via the manipulation of two interrelated systems that bind human choice to a structure of opportunities and constraints. The first of these is the bynow familiar natural ecosystem that determines the costs and benefits of different production strategies (Trigger 1991). The second is the system of social alliances that structures access to resources and power on the basis of gender, class, and factional affiliation. Besides determining peoples ability to achieve their goals, the social system also determines, in many ways, what those goals will be: alliance, surplus extraction, usurpation, resistance, liberation, and so on. Thus, we must analyze social as well as ecological variables, what Flannery (1988:58), getting it half right, anyway, has called man-man and man-land relationships (also see Adams 1966). In particular, we must insert social power as a primary structural variable (Wolf 1990). We must analyze how alliance networks controlling labor and resources are constructed on the basis of gender, class, and factional affiliation, and we must study how individuals and groups contrive to bring about transformations in the membership and resources controlled by these networks. Fourth, to analyze specific sequences of change, it will be necessary to alternate between a subject-centered and a system-centered analysis (Giddens 1979). A subject-centered analysis organizes ecological and social variables by weighing them according to their importance in specific behavioral strategies. A system-centered analysis reveals how the implementation of these strategies alters the quality and distribution of ecological and social resources among the groups, creating new strategic possibilities for the next round of behavior. Verifying the existence of strategic action in the archeological record will not differ in principle from the way that subsistence strategies are verified in the ecosystem approach. In ecosystem theory, many artifact classes, settlement pattern types, and the like, have been assigned functions within reconstructed subsistence strategies on the basis of their technical properties, ethnographic analogy, and archeological contexts. These same approaches may be used to assign functions to classes of data in reconstructed social strategies. These strategies will leave distinctive imprints on such aspects of the archeological record as house size and plan, and surplus storage facilities (Saitta and Keene 1990). In addition, many attributes of ceramics, burials, architecture, personal adornment, and the use of space, which have been considered stylistic from the viewpoint of ecosystem theory, may be understood as expressions of claims and counterclaims in ongoing social negotiation (Hodder 1986:8; Shanks and Tilley 1987:133; for examples see Hodder 1982; Miller and Tilley 1984; Fritz 1986; Small 1987; Moore 1986; Brumfiel and Earle 1987b; Brumfiel

560

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[94, 1992

1987a, 1987b, 1990; Brumfiel, Salcedo, and Schafer 1993; McGuire and Paynter 1991). Contrary to Hodder (1986:6) and Shanks and Tilley (1987:132), the discourse of social negotiation can be studied cross-culturally; similar ecological and social strategies should leave broadly similar imprints on material culture. The analytical principles I have suggested here represent a clear departure from traditional ecosystem theory. This departure should enable us to account more adequately for the full range ofarcheological data at our disposal, including variation in the intensity of household production, variation in household composition and organization, variation in demographic trends, the occurrence of enclave economies and prestige economies, and the intensity and organization ofwarfare and surplus extraction. The approach suggested here should also enable us to create a more humane archeology, an archeology that will acknowledge the creativity and discretion that women and men, subjects and rulers have exercised in the past to fashion their livelihoods and promote their well-being.

Notes

Acknowledgments. This paper has benefited immensely from the comments and criticisms offered by Len Berkey, Michael Blake, Mary Collar,John Clark, George Cowgill, Antonio Gilman, Mary Hodge, Roberto Korzeniewicz, Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Tom Patterson, Glenn Perusek, Henry Wright, Rita Wright, and members of the Department of Anthropology, New York University, where an earlier version of this paper was presented. I am very grateful for their help. This is in keeping with the idea of at least some ecosystem theorists that explanation in archeology would consist oflaws of correlation, rather than laws ofconnection (Wylie 1982386). For example, Binford (1962:218) defines scientific explanation as the demonstration of a constant articulation ofvariables within a system and the measurement of the concomitant variability among the variables within the system. This definition betrays an interest in systemic function rather than systemic structure, that is, a concern with what the system does as opposed to how it operates (see Salmon 1978: 175). 21n fact, Redman (1978b3341) regards the self-interested activities of the elite as a major process leading to the emergence of social complexity: the elite . . . were participants in the fifth positive feedback relationshipthat is, purposeful strategies of the elite to stimulate further growth of the institutions that gave them their power and wealth. 3Adamss (1974) examination of Mesopotamian ecology from the viewpoint of the individual peasant producer offers interesting contrasts to Redmans (1978a229-236) more system-focused approach.

References Cited

Adams, Robert McC. 1966 The Evolution of Urban Society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehispanic Mexico. Chicago: Aldine. 1974 The Mesopotamian Social Landscape: A View from the Frontier. In Reconstructing Complex Societies. C. B. Moore, ed. Pp. 1-1 1. Chicago: Supplement to the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 20. 1978 Strategies of Maximization, Stability, and Resilience in Mesopotamian Society, Settlement, and Agriculture. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 122329-335. Barfield, Thomas J. 1989 The Perilous Frontier. London: Basil Blackwell. Bartlett, K. 1933 Pueblo Milling Stones of the Flagstaff Region and Their Relation to Others in the Southwest: A Study in Progressive Efficiency. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona, Bulletin No. 3. Bender, Barbara 1978 Gatherer-Hunter to Farmer: A Social Perspective. World Archaeology 10:204-222. Binford, Lewis R. 1962 Archaeology as Anthropology. American Antiquity 28:217-225. Blanton, Richard E. 1975 The Cybernetic Analysis of Human Population Growth. In Population Studies in Archaeology and Biological Anthropology: A Symposium. A. c. Swedlund, ed. Pp. 116-126. Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology Memoirs, 30.

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

56 1

Blanton, Richard E., Stephen A. Kowalewski, Gary Feinman, and Jill Appel 1981 Ancient Mesoamerica: A Comparison of Change in Three Regions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Blaut, James M. 1987 The National Question: Decolonising the Theory of Nationalism. London: Zed Books. Boyd, Robert, and Peter J. Richerson 1985 Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Braun, David P. 1981 Pots as Tools. In Archaeological Hammers and Theories. J. A. Moore and A. S. Keene, eds. Pp. 108-134. New York: Academic Press. 1990 Selection and Evolution in Nonhierarchical Organization. In The Evolution of Political Systems. S. Upham, ed. Pp. 62-86. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Braun, David P., and Stephen Plog 1982 Evolution of Tribal Social Networks: Theory and Prehistoric North American Evidence. American Antiquity 47:504-525. Bronson, Bennet 1988 The Role of Barbarians in the Fall of States. In The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations. N. Yoffee and G. L. Cowgill, eds. Pp. 196-218. Tucson: University ofArizona Press. Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. 1987a Elite and Utilization Crafts in the Aztec State. In Specialization, Exchange, and Complex Societies. E. M. Brumfiel and T. K. Earle, eds. Pp. 102-1 18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1987b Consumption and Politics at Aztec Huexotla. American Anthropologist 89:676-686. 1990 Figurines, Ideological Domination and the Aztec State. Paper presented at the 89th annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, New Orleans, Louisiana. 1991 Weaving and Cooking: Womens Production in Aztec Mexico. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 224-251. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Brumfiel, Elizabeth M., and Timothy K. Earle 1987a Specialization, Exchange, and Complex Societies: An Introduction. In Specialization, Exchange, and Complex Societies. E. M. Brumfiel and T. K. Earle, eds. Pp. 1-9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1987b [eds.] Specialization, Exchange, and Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brumfiel, Elizabeth M., and John W. Fox, eds. 1993 Factional Competition and Political Development in the New World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (In press.) Brumfiel, Elizabeth M., Tamara Salcedo, and David K. Schafer 1993 The Lip Plugs of Xaltocan: Function and Meaning in Aztec Archaeology. In Economies and Polities in the Aztec Realm. M. G. Hodge and M. E. Smith, eds. New York: State University of New York Press, Latin American Series. (In press.) Burling, Robbins 1974 The Passage of Power: Studies in Political Succession. New York: Academic Press. Chevillard, Nicole, and Stbastien Leconte 1986 The Dawn of Lineage Societies: The Origins of Womens Oppression. In Womens Work, Mens Property. S. Coontz and P. Henderson, eds. Pp. 76-107. London: Verso. Claassen, Cheryl P. 1991 Gender, Shellfishing, and the Shell Mound Archaic. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 276-300. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Clark, John E. 1988 The Lithic Artifacts of La Libertad, Chiapas, Mexico. Provo, UT: New World Archaeological Foundation Papers, 52. Clark, John E., and Michael Blake 1993 The Power of Prestige: Competitive Generosity and the Emergence of Rank Societies in Lowland Mesoamerica. In Factional Competition and Political Development in the New World. E. M. Brumfiel and J. W. Fox, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (In press.) Clarke, David L. 1968 Analytical Archaeology. London: Methuen.

562

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[94,1992

1972 A Provisional Model of an Iron Age Society. In Models in Archaeology. D. L. Clarke, ed. Pp. 801-869. London: Methuen. Conkey, Margaret W., and Joan M. Gero 1991 Tensions, Pluralities, and Engendering Archaeology: An Introduction to Women and Prehistory. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 3-30. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Conkey, Margaret W., and Janet D. Spector 1984 Archaeology and the Study of Gender. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 7: 1-38. Coontz, Stephanie, and Peta Henderson 1986 Property Forms, Political Power and Female Labour in the Origins of Class and State Societies. In Womens Work, Mens Property. S. Coontz and P. Henderson, eds. Pp. 108-155. .London: Verso. Costin, Cathy L. 1986 From Chiefdom to Empire State: Ceramic Economy among the Prehispanic Wanka of Highland Peru. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles. Cowgill, George L. 1975 On Causes and Consequences of Ancient and Modern Population Changes. American Anthropologist 7 7:505-525. DAltroy, Terrance, and Timothy Earle 1985 Staple Finance, Wealth Finance, and Storage in the Inka Political Economy. Current Anthropology 26: 187-206. Dunnell, Robert C. 1980 Evolutionary Theory and Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 3:35-99. Durham, William H. 1990 Advances in Evolutionary Culture Theory. Annual Review of Anthropology 19:187-2 10. Earle, Timothy K. 1978 Economic and Social Organization of a Complex Chiefdom: The Halelea District, Kauai, Hawaii. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers, 63. 1987 Specialization and the Production of Wealth: Hawaiian Chiefdoms and the Inka Empire. In Specialization, Exchange, and Complex Societies. E. M. Brumfiel and T. K. Earle, eds. Pp. 64-75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1991 Toward a Behavioral Archaeology. In Processual and Postprocessual Archaeologies. R. W. Preucel, ed. Pp. 83-95. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper No. 10. Eisenstadt, S. N. 1963 The Political Systems of Empires. New York: Free Press. Fallers, Lloyd A. 1956 Bantu Bureaucracy: A Century of Political Evolution among the Basoga of Uganda. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Flannery, Kent V. 1967 Culture History v. Cultural Process: A Debate in American Archaeology. Scientific American 217:119-122. 1968a Archeological Systems Theory and Early Mesoamerica. In Anthropological Archeology in the Americas. B. J. Meggers, ed. Pp. 67-87. Washington, DC: Anthropological Society of Washington. 1968b The Olmec and the Valley of Oaxaca. In Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec. E. P. Benson, ed. Pp. 79-1 10. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. 1972 The Cultural Evolution of Civilizations. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3:399-426. 1988 Comment on Sanders and Nichols Ecological Theory and Cultural Evolution in the Valley of Oaxaca. Current Anthropology 29:58. Flannery, Kent V., and Marcus C. Winter 1976 Analyzing Household Activities. In The Early Mesoamerican Village. K. V. Flannery, ed. Pp. 34-47. New York: Academic Press.

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

563

Fortes, M., and E. E. Evans-Pritchard 1940 Introduction. In African Political Systems. F. Fortes and E. E. Evans-Pritchard, eds. Pp. 1-23. London: Oxford University Press. Fox, Richard G., and Allen Zagarell 1982 The Political Economy of Mesopotamian and South Indian Temples: The Formation and Reproduction of Urban Society. Comparative Urban Research 9:8-27. Friedman, Jonathan 1977 Tribes, States, and Transformations. In Marxist Analyses and Social Anthropology. M. Bloch, ed. Pp. 201-276. New York: Wiley. Fritz, John M. 1986 Vijayanagara: Authority and Meaning of a South Indian Imperial Capital. American Anthropologist 88:44-55. Gailey, Christine W. 1985a The State of the State in Anthropology. Dialectical Anthropology 9:65-88. 1985b The Kindness of Strangers: Transformations of Kinship in Precapitalist Class and State Formation. Culture 5(2):3- 16. 1987 Kinship to Kingship: Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands. Austin: University of Texas Press. Gall, Patricia L., and Arthur A. Saxe 1977 The Ecological Evolution ofCulture: The State as Predator in Succession Theory. In Exchange Systems in Prehistory. T. K. Earle and J. E. Ericson, eds. Pp. 255-268. New York: Academic Press. Giddens, Anthony 1979 Central Problems in Social Theory. Berkeley: University of California Press. Gilman, Antonio 1981 The Development of Social Stratification in Bronze Age Europe. Current Anthropolog 22:1-23. Gluckman, Max 1956 Custom and Conflict in Africa. New York: Barnes and Noble. Goody, Jack 1966 Introduction. In Succession to High Office. J. Goody, ed. Pp. 1-56. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Halstead, Paul, and John OShea 1982 A Friend in Need Is a Friend Indeed: Social Storage and the Origins of Social Ranking. In Ranking, Resource and Exchange. C. Renfrew and S. Shennan, eds. Pp. 92-99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Harris, David R. 1977 Alternative Pathways toward Agriculture. In Origins of Agriculture. C. A. Reed, ed. Pp. 179-243. The Hague: Mouton. Hartmann, Heidi 1981 The Family as the Locus ofGender, Class, and Political Struggle: The Example ofHousework. Signs 6:366-394. Hassan, Fekri A. 1981 Demographic Archaeology. New York: Academic Press. Hastorf, Christine A. 1991 Gender, Space, and Food in Prehistory. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 132-159. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Hastorf, Christine A., and SisselJohannessen 1991 Understanding Changing People/Plant Relationships in the Prehispanic Andes. In Processual and Postprocessual Archaeologies. R. w . Preucel, ed. Pp. 140-155. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper No. 10. Hayden, Brian 1981 Research and Development in the Stone Age: Technological Transitions among Hunter/ Gatherers. Current Anthropology 2 2 5 19-548. 1990 Nimrods, Piscators, Pluckers, and Planters: The Emergence of Food Production. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 9:3 1-69. Helms, Mary W. 1979 Ancient Panama: Chiefs in Search of Power. Austin: University ofTexas Press.

564

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOCtST

[94, 1992

Hicks, Frederic 1993 Alliance and Intervention in Aztec Imperial Expansion. In Factional Competition and Political Development in the New World. E. M. Brumfiel and J. W. Fox, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (In press.) Hill, James N. 1977 Systems Theory and the Explanation of Change. In Explanation of Prehistoric Change. J. N. Hill, ed. Pp. 59-103. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Hodder, Ian 1982 [ed.] Symbolic and Structural Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1986 Reading the Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jackson, Thomas L. 1991 Pounding Acorn: Womens Production as Social and Economic Focus. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 301-325. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Johnson, Gregory A. 1978 Information Sources and the Development of Decision-Making Organizations. In Social Archeology. C. L. Redman et al., eds. Pp. 87-1 12. New York: Academic Press. Kaufman, Herbert 1988 The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations as an Organizational Problem. In The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations. N. Yoffee and G. L. Cowgill, eds. Pp. 219-235. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Keene, Arthur S. 1979 Economic Optimization Models and the Study of Hunter-Gatherer Subsistence Settlement Systems. In Transformations: Mathematical Approaches to Culture Change. C. Renfrew and K. Cooke. eds. Pp. 369-404. New York: Academic Press. Kehoe, Alice B. 1990 Points and Lines. In Powers ofobservation: Alternative Views in Archeology. S. M. Nelson and A. B. Kehoe, eds. Pp. 23-37. Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association, Archeological Papers, No. 2. King, Thomas F. 1978 Dont that Beat the Band? Nonegalitarian Political Organization in Prehistoric Central California. In Social Archeology. C. L. Redman et al., eds. Pp. 225-248. New York: Academic Press. Kohl, Philip L. 1981 Materialist Approaches in Prehistory. Annual Review of Anthropology 10:89-118. Kristiansen, Kristian 1981 Economic Models for Bronze Age Scandinavia-Towards an Integrated Approach. In Economic Archaeology: Towards an Integration of Ecological and Social Approaches. A. Sheridan and G. Bailey, eds. Pp. 239-303. BAR International Series, 96. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. Lattimore, Owen 1951 Inner Asian Frontiers of China. Boston: Beacon Press. Lenin, V. I. 1939 Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. New York: International. Lewis, Oscar 1942 The Effects of White Contact upon Blackfoot Culture. American Ethnological Society Monographs, 6. Seattle: University of Washington Press. McGuire, Randall H. 1983 Breaking Down Cultural Complexity: Inequality and Heterogeneity. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 6:91-142. McGuire, Randall H., and Robert Paynter, eds. 1991 The Archaeology of Inequality. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Miller, Daniel, and Christopher Tilley, eds. 1984 Ideology, Power and Prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Moore, Henrietta 1986 Space, Text and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990 Gender Relations and the Modelling of the Economy. Paper presented at the 10th annual meeting of the Society for Economic Anthropology, Tucson, Arizona.

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

565

Nelson, Sarah M. 1990 Diversity of the Upper Paleolithic Venus Figurines and Archeological Mythology. In Powers of Observation: Alternative Views in Archeology. S. M. Nelson and A. B. Kehoe, eds. Pp. 1 1-22. Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association, Archeological Papers, No. 2. Orlove, Benjamin S. 1980 Ecological Anthropology. Annual Review of Anthropology 9:235-273. Patterson, Thomas C. 1991a Race and Archaeology: A Comparative and Historical View. Paper presented at the 90th annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association. Chicago, Illinois. 1991b The Inca Empire: The Formation and Disintegration of a Pre-Capitalist State. New York: Berg. 1992 Archaeology: The Historical Development of Civilizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. (In press.) Paynter, Robert 1989 The Archaeology of Equality and Inequality. Annual Review of Anthropology 18:369399. Price, Barbara J. 1982 Cultural Materialism: A Theoretical Review. American Antiquity 47:709-741. Rapp, Rayna 1978 The Search for Origins: Unraveling the Threads of Gender Hierarchy. Critique of Anthropology 3:5-24. Redman, Charles L. 1978a The Rise ofcivilization. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman. 1978b Mesopotamian Urban Ecology: The Systemic Context of the Emergence of Urbanism. In Social Archeology. C. L. Redman et al., eds. Pp. 329-347. New York: Academic Press. Rowlands, Michael 1980 Kinship, Alliance and Exchange in the European Bronze Age. In Settlement and Society in the British Later Bronze Age. J. Barrett and R. Bradley, eds. Pp. 15-55. BAR British Series, 83. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. Sahlins, Marshall 1968 Tribesmen. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 1972 Stone Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine. Saitta, Dean J.,and Arthur S. Keene 1990 Primitive Communism and the Origin of Social Inequality. In The Evolution of Political Systems. S. Upham, ed. Pp. 203-224. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Salmon, Merrilee H. 1978 What Can Systems Theory Do for Archaeology? American Antiquity 43:174-183. Sanders, William T., Jeffrey R. Parsons, and Robert S. Santley 1979 The Basin of Mexico. New York: Academic Press. Sanders, William T., and Barbara J. Price 1968 Mesoamerica: The Evolution of a Civilization. New York: Random House. Santley, Robert S. 1980 Disembedded Capitals Reconsidered. American Antiquity 45: 132- 145. Shanks, Michael, and Christopher Tilley 1987 Re-Constructing Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shennan, Stephen J . 1991 Tradition, Rationality, and Cultural Transmission. In Processual and Postprocessual Archaeologies. R. W. Preucel, ed. Pp. 197-208. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper No. 10. Silverblatt, Irene 1987 Moon, Sun, and Witches: Gender Ideologies and Class in Inca and Colonial Peru. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 1988 Women in States. Annual Review of Anthropology 17:427-460. Small, David B. 1987 Toward a Competent Structuralist Archaeology: Contribution from Historical Studies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 6: 105-1 2 1.

566

AMERICAN

ANTHROPOLOGIST

194, 1992

Stahl, Ann B. 1989 Plant-Food Processing: Implications for Dietary Quality. In Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation. D. R. Harris and G. C. Hillman, eds. Pp. 171-194. London: Unwin Hyman. Stanish, Charles 1989 Household Archeology: Testing Models of Zonal Complementarity in the South Central Andes. American Anthropologist 91 :7-24. Steward, Julian H. 1955 The Concept and Method ofCultural Ecology. In Theory ofculture Change. Pp. 30-42. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Struever, Stuart, and Felicia Antonelli Holton 1979 Koster: Americans in Search ofTheir Prehistoric Past. New York: Signet. Terray, Emmanuel 1979 Long-Distance Trade and the Formation of the State: The Case of the Abron Kingdom of Gyaman. In Toward a Marxist Anthropology. S. Diamond, ed. Pp. 291-320. The Hague: Mouton. Trigger, Bruce G. 1991 Distinguished Lecture in Archeology: Constraint and Freedom-A New Synthesis for Archeological Explanation. American Anthropologist 93:55 1-569. Tringham, Ruth E. 1991 Households with Faces: The Challenge of Gender in Prehistoric Architectural Remains. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 93-131. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Tymowski, Michal 1991 Wolof Economy and Political Organization: The West African Coast in the Mid-Fifteenth Century. In Early State Economics. H. J. M. Claessen and P. van de Velde, eds. Pp. 131-142. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Watson, Patty Jo, and Mary Kennedy 1991 The Development ofHorticulture in the Eastern Woodlands of North America: Womens Role. In Engendering Archaeology. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 255-275. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Webster, David 1975 Warfare and the Evolution of the State: A Reconsideration. American Antiquity 40:464470. 1976 On Theocracies. American Anthropologist 78:812-828. Weiner, Annette B., and Jane Schneider, eds. 1989 Cloth and Human Experience. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. White, Leslie A. 1949 The Science ofculture. New York: Grove. 1959 The Evolution of Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill. Wilk, Richard R., and Wendy Ashmore, eds. 1988 House and Household in the Mesoamerican Past. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Wilk, Richard R., and William J. Rathje, eds. 1982 Archaeology of the Household: Building a Prehistory of Domestic Life. American Behavioral Scientist 25(6). Williams, Brackette F. 1989 A Class Act: Anthropology and the Race to Nation across Ethnic Terrain. Annual Review of Anthropology 18:401-444. Winterhalder, Bruce, and Eric Alden Smith, eds. 1981 Hunter-Gatherer Foraging Strategies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Wolf, Eric R. 1982 Europe and the People without History. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1990 Distinguished Lecture: Facing Power-Old Insights, New Questions. American Anthropologist 92:586-596. Wright, Henry T. 1970 Toward an Explanation of the Origin of the State. Paper presented at the School of American Research symposium, Explanation of Prehistoric Organizational Change, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Brumfiel]

DISTINGUISHED

LECTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY

567

1977 Recent Research on the Origin of the State. Annual Review of Anthropology 6:379-397. Wylie, Alison 1982 An Analogy by Any Other Name Is Just as Analogical. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1:382-401. Yoffee, Norman 1979 The Decline and Rise of Mesopotamian Civilization: An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective on the Evolution of Social Complexity. American Antiquity 44:5-35. Yoffee, Norman, and George L. Cowgill, eds. 1988 The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Zagarell, Allen 1986 Trade, Women, Class, and Society in Ancient Western Asia. Current Anthropology 2 7 ~ 15-430. 4

You might also like

- AcharyaPK ArchitectureOfManasaraTranslationDocument246 pagesAcharyaPK ArchitectureOfManasaraTranslationCharlie Higgins67% (3)

- Everyday Life in Babylon and AssyriaDocument8 pagesEveryday Life in Babylon and AssyriaCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Technique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaDocument3 pagesTechnique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Dellovin ACarpenter'sToolKitCentralWesternIranDocument27 pagesDellovin ACarpenter'sToolKitCentralWesternIranCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Eguchi MusicAndReligionOfDiasporicIndiansInPittsburgDocument116 pagesEguchi MusicAndReligionOfDiasporicIndiansInPittsburgCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Meyer SexualLifeInAncientIndiaDocument616 pagesMeyer SexualLifeInAncientIndiaCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Moorey AncientMesopotamianMaterialsAndIndustriesDocument224 pagesMoorey AncientMesopotamianMaterialsAndIndustriesCharlie Higgins100% (3)

- Bourriau PotteryFromNileBeforeArabConquestDocument12 pagesBourriau PotteryFromNileBeforeArabConquestCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Look at The Use of The Potter's Wheel in Bronze Age GreeceDocument9 pagesA Comparative Look at The Use of The Potter's Wheel in Bronze Age GreeceCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Dalrymple LutePlusVinaEqualsSitarDocument10 pagesDalrymple LutePlusVinaEqualsSitarCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Schenk DatingHistoricalValueRoulettedWareDocument30 pagesSchenk DatingHistoricalValueRoulettedWareCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Apostila PronounsDocument4 pagesApostila PronounsCristiane NascimentoNo ratings yet

- ANT 1101 Course Outline 2023Document2 pagesANT 1101 Course Outline 2023Martin chisaleNo ratings yet

- Ramírez, Rafael L. Et Al. (Eds.) - Caribbean Masculinities Working Papers (CIEVS, 2002)Document200 pagesRamírez, Rafael L. Et Al. (Eds.) - Caribbean Masculinities Working Papers (CIEVS, 2002)Raúl Vázquez100% (1)

- Folktale of SangkuriangDocument2 pagesFolktale of SangkuriangAlya annisa100% (1)

- Cambridge University PressDocument3 pagesCambridge University PressGracelia Apriela Koritelu100% (2)

- The Demonic Lore of Ancient Egypt Quest PDFDocument42 pagesThe Demonic Lore of Ancient Egypt Quest PDFAankh Benu100% (1)

- Diemberger CV 2015Document6 pagesDiemberger CV 2015TimNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistics 1 - What Is SociolinguisticsDocument28 pagesSociolinguistics 1 - What Is Sociolinguisticsman_dainese93% (15)

- Greek Mythology and Saipan Legends On CreationismDocument10 pagesGreek Mythology and Saipan Legends On CreationismChelsea EncioNo ratings yet

- The Epic of GilgameshDocument23 pagesThe Epic of GilgameshAbed DannawiNo ratings yet

- Vanderbilt University Press Fall/Winter 2018 CatalogDocument12 pagesVanderbilt University Press Fall/Winter 2018 CatalogVanderbilt University PressNo ratings yet

- Health Policy and System Research A Methodology Reader PDFDocument474 pagesHealth Policy and System Research A Methodology Reader PDFRama GrivandoNo ratings yet

- Bergonzi PatternsDocument2 pagesBergonzi Patternsatste100% (6)

- Unmyst3 Blogspot GR 2013 09 Vrykolakas Greek Vampire HTMLDocument5 pagesUnmyst3 Blogspot GR 2013 09 Vrykolakas Greek Vampire HTMLblackguard999No ratings yet

- Mead and Bali DanceDocument27 pagesMead and Bali Dancedario lemoliNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 58 Fourth Quarter - 03 - Owen J. Lynch, JR - The Philippine Indigenous Law Collection PDFDocument78 pagesPLJ Volume 58 Fourth Quarter - 03 - Owen J. Lynch, JR - The Philippine Indigenous Law Collection PDFTimothy Ryan Wang100% (1)

- Shibi CriticDocument28 pagesShibi Criticssuscritical100% (2)

- 13 Must Visit MuseumDocument24 pages13 Must Visit MuseumAnthony Rey BayhonNo ratings yet

- Iggers, Georg - Historiography in The Twentieth CenturyDocument24 pagesIggers, Georg - Historiography in The Twentieth CenturyVanessa AlbuquerqueNo ratings yet

- 1 Some Key Heka Concepts - Doc - 1428945534177Document2 pages1 Some Key Heka Concepts - Doc - 1428945534177Jacque Van Der BergNo ratings yet

- S A U S: Erpent Cross THE Nited TatesDocument1 pageS A U S: Erpent Cross THE Nited TatesChris MooreNo ratings yet

- Strathern, M. Reading Relation BackwardsDocument17 pagesStrathern, M. Reading Relation BackwardsFernanda HeberleNo ratings yet

- The New Phenomenology - Recommend Chapter FiveDocument421 pagesThe New Phenomenology - Recommend Chapter FiveShemusundeen Muhammad100% (3)

- A Brief Note On John MiltonDocument4 pagesA Brief Note On John MiltonJacinta DarlongNo ratings yet

- Arizona's GoblinsDocument1 pageArizona's GoblinsJoe DurwinNo ratings yet

- BOHANNAN, Paul. Introduction. In. Beyond The Frontier - Social Process and Cultural Change.Document7 pagesBOHANNAN, Paul. Introduction. In. Beyond The Frontier - Social Process and Cultural Change.WemersonFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Miller - Photography in The Age of SnapchatDocument22 pagesMiller - Photography in The Age of SnapchatNhật Lam NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Riles Annelise Network Inside Out COMPLETODocument133 pagesRiles Annelise Network Inside Out COMPLETOIana Lopes AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Landscapes in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesLinguistic Landscapes in The PhilippinesAmiel DemetrialNo ratings yet

- Mythology As PoeticsDocument85 pagesMythology As PoeticssuprndNo ratings yet