Professional Documents

Culture Documents

4LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Reply Sentencing Memo

Uploaded by

Helen BennettCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

4LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Reply Sentencing Memo

Uploaded by

Helen BennettCopyright:

Available Formats

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 1 of 26

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CRIMINAL NO. 3:10CR 237 (AWT) v. February 23, 2014 GREGORY P. LOLES

GOVERNMENT=S SUPPLEMENTAL REPLY MEMORANDUM IN AID OF SENTENCING

This memorandum is submitted in further aid of the sentencing of Defendant Gregory P. Loles, who stole more that $27 million from friends, clients, the endowment fund and building fund of a Church in Orange, Connecticut, St. Barbara=s Greek Orthodox Church (Athe Church@ or ASt. Barbara=s@), and as recently corroborated, from a Greek family overseas. Additionally, this memorandum is submitted in response to defendants recently advanced arguments for a significantly below Guidelines sentence as argued in Defendants Final Sentencing Memorandum (Def. Mem. Dkt. No. 164). As set forth below and as established at the multiple hearing in this matter, the arguments advanced by counsel to not support the drastic remedy he seeks of a significantly below Guidelines sentence. I. General Overview

As previously argued, under the circumstances of this case the defendants total offense level could be determined to be as high as a level 49. The defendant reaches this level because at every turn and at nearly every opportunity for the past 15 or more years he has been evasive,

1

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 2 of 26

deceitful, and wholly dishonest. He lied to his friends, his family, his community, his parish priest, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Bureau of Investigations, the Internal Revenue Service by failing to file his taxes since 2004, and most recently he has taken his dishonesty with him to the witness stand and lied to the Court. He has attempted to present himself as contrite and remorseful but has consistently sought to mislead, dissemble, and continually scheme a way through his legal morass. Most recently, he had the temerity to testify under oath that $14 million of funds that he took from a Greek family, after the father of that family had unexpectedly died, was in fact his money. The clear falsity of this statement was demonstrated at length by the Government in its prior filing (Doc. No. 163) but is also underscored by the fact that defense counsel has now argued that the Greek family should not based on an unsupported and unsupportable reason receive restitution. Had it actually been Loles money, no such argument would even need to be advanced. Loles defrauded well more than 250 victims out of more than $27 million. He held himself out as representing a charitable and religious organization by not only claiming to manage the money of the church all the while taking it, but also by endeavoring to coordinate a stock purchase plan to generate a commission or donation that was to go to the Church but which he took for himself almost immediately. He used sophisticated means by creating false account statements and false tax documents. Notable, he created genuine tax documents that caused many of his victims to pay taxes on the fictitious interest. He held himself out as a broker and investment advisor on various forms and continued to run an advertisement for his services in the church bulletin. Moreover, he was trained as an investment advisor and held a Series 7, a Series 63, and a Series 65, licenses which no doubt provided him additional training and experience to execute such a sophisticated financial crime.

2

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 3 of 26

After taking in the victim-investor funds, Loles moved his ill-gotten gains from account to account in order to promote and perpetrate the scheme, including moving money to Apeiron accounts and Knightsbridge accounts to make it appear as if the funds were investment related funds and moving other money to his Farnbacher-Loles accounts to make it appear as if those funds were car racing business related. Loles has failed to show remorse and, as mentioned, lied to the FBI about the source of $14 million in his account and also lied to the Court about this money, thus preventing himself form getting the benefit of any acceptance of responsibility. It also bears mention as to how Loles chose to spend the $27 million that he stole. He bought a large house, with a pool and tennis courts, with a multi-car garage for his numerous sports cars. (See Attachments C and D). He ran a sport-car racing business which was less like a business and more of a fun hobby because Loles never managed to turn a profit. (See Attachment A and B). Loles sent his children to excellent schools and travel internationally. Based on records received from the IRS and the Social Security Administration, he hasnt had a paying job in many years, and has been living off the money of his victims. For example, between 2000 and 2009, the most he ever reported as income was in 2003 when he reported AGI of $32,215 and the same year he took in over $800,000 into his personal accounts. No matter what the eventual Guidelines calculation the Court determines is legally proper, there can be no doubt that the Court should not hesitate to give Defendant Loles an appropriately long period of incarceration, because such a long prison term of, for example 360 months or more, is necessary to achieve the goals of sentencing. Were the Court to give a term of incarceration consistent with that sought by defense counsel, the Court would not be giving proper weight to the seriousness of the crime, the large dollar loss, the large number of victims, the fact that Loles was acting as an investment advisor, and the fact that he was acting on behalf of a charitable and

3

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 4 of 26

religious organization while committing his crimes. Moreover, there needs to be included in the term of incarceration a significant period of time because of the fact that Loles lied to the FBI and then lied to the Court. For the reasons set forth in the Government=s Original Sentencing Memorandum (Dkt. No. 80), those set forth in the Governments Reply Memorandum (Dkt. No. 89), those set forth in open Court at the multi-day hearing, and those set forth in the Governments Supplemental Sentencing Memorandum (Dkt. No. 163), and those set forth herein, the Government asserts that the Court should not hesitate to impose a sentence at or near the ultimate Guidelines range as the Court shall determine. Thus, the sentence should be or exceed 360 months. II. None of The Sought-After Downward Departures are Appropriate

The defendant argues that the Court should consider a non-Guideline sentence or a downward departure based on: (i) the argument that he has provided some cooperation in determining the scope of his own case and an additional case brought by another section of the Department of Justice; (ii) his purported low likelihood of recidivism given his ban by the SEC from serving in the investment industry; (iii) the fact that he has worked hard his whole life (which ironically includes this nearly nine-plus years-long $27 million dollar Ponzi scheme); (iv) the punishment he has already suffered by among other arguments, the humiliation and family impact caused by being prosecuted and incarcerated; and (v) what generally appears to be the totality of the circumstances, including other fraud cases in this District. None of these requests either taken together or in combination support the granting of a departure or the imposition of a below Guidelines sentence and accordingly, these requests should be rejected. First, the Sentencing Guidelines provide a framework applicable to a heartland of cases. The statutory reason for promulgating the Sentencing Guidelines was the recognition of the need

4

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 5 of 26

to avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants with similar records who have been found guilty of similar conduct. 18 U.S.C. 3553(a)(6). A sentencing court dealing with an atypical case has flexibility to depart from the proscribed Guidelines provided facts are present of a kind or to a degree not contemplated by the Sentencing Commission. Although the Guidelines afford the district court flexibility in sentencing, the Second Circuit has instructed that the power to depart should be used sparingly and should be reserved for unusual cases. See United States v. Williams, 37 F.3d 82, 85 (2d Cir. 1994); United States v. Core, 125 F.3d 74, 79 (2d Cir. 1997). The Second Circuit has characterized the heartland departure as a discouraged departure. United States v. Broderson, 67 F.3d 452, 458 (2d Cir. 1995). A sentencing court should only consider such a departure when there are compelling considerations that take the case out of the heartland factors upon which the Guidelines rest. United States v. Chabot, 70 F.3d 259, 262 (2d Cir. 1995). The Supreme Court has said that the sentencing court, in resolving whether a particular case is within the heartland, must make a refined assessment of the many facts of the case in comparison with the facts of other Guidelines cases, using its day to day experience in criminal sentencing to determine whether the factor in the case at hand is present in some unusual or exceptional way. Koon v. United States, 518 U.S. 81, 98 (1996). The defendant bears the burden of establishing that he should receive a downward departure. See United States v. Silleg, 311 F.3d 557, 564 (2d Cir. 2002); United States v. Harris, 79 F.3d 223, 233 (2d Cir. 1996). Loles has failed to carry this burden. A. The Offense Level Does Not Overstate the Seriousness of the Offense

Defendant argues for a downward departure is his claim that the adjusted Guideline range in essence overstates the seriousness of the offense and claims that the Guidelines are not based

5

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 6 of 26

on empirical evidence or national experience. (Def. Mem. Dkt. No. 164 at 12). This argument is without merit and is contrary to controlling law that the Guidelines are to be the starting point. As the Supreme Court has held, because the Guidelines are the product of careful study based on extensive empirical evidence derived from the review of thousands of individual sentencing decisions, Gall v. United States, 128 S. Ct. 586, 594 (2007), district courts must treat the Guidelines as the starting point and the initial benchmark in sentencing proceedings. Id. at 596. B. Loles Did Not Provide Assistance

Counsel also argues in his recent memorandum (Def. Mem. Dkt. No. 164 at 3-4) that Loles assisted in determining the extent of the fraud, and should get some consideration for helping the FBI investigate his crime. This is simply not true. Loles created the appearance of trying to help the FBI and seemed to recall small repayments to victims or small donations to the Church like purchasing Greek iconography for the church (approximately $45,000), but all the while he repeated lied about the $14 million taken in from Milbury Holdings. Counsel argues that Loles narrowed the difference between the defense and the prosecution. However, in retrospect, Loles was not attempting to reveal the truth but was simply trying to negotiate the loss amount below the threshold of $7 million, all the while trying to hide the fact that he had stolen an additional $14 million from a Greek family that the Government was not focusing on at the time. The tens and even hundreds of hours that Loles caused the prosecution team to expend after his initial plea, as well has his evasive and false testimony before the Court, must be recognized with additional period of time included in the ultimate period of incarceration for the purposes of punishment as well as specific and general deterrence. Loles was evasive on the stand and sought to mislead the Court about Fantasma toys, thus causing a victim to return home to research his old files searching for receipts to rebut Loles

6

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 7 of 26

insinuations. Loles was extremely evasive about the New Haven Savings Bank transactions and whether the Church received a commission a fee or a donation. None of which actually went to the ultimate issue that he ended up with the nearly $1 million. Moreover, Loles lied to the Court about the Greek familys investment. This conduct does not amount to assistance and does not merit a departure. Additionally, Loles did not provide substantial assistance nor any measureable assistance, from his incarceration in Wyatt, regarding an unrelated investigation prosecuted by the Department of Justice Public Integrity Section and cannot claim any credit for that case. In fact, the view of the Greek family held by the line prosecutor is dramatically different from what Loles seeks to present. C. Loles did Not Work-Hard His Whole Life and No Departure is Warranted

Loles also argues that his excellent work history supports a departure. However, over the last 9 or more years prior to his arrest, from approximately 2001, Loles was conducting a fraud and had no legitimate job. He cannot argue that he had an excellent work history when he has not had legal employment for nearly a decade. Moreover, his employment history as reflected in the Social Security Administrations Records is slim at best. Nonetheless, even if he did have a strong work history, the Second Circuit has held, a defendants employment record is not ordinarily relevant and will warrant departure in a relatively few instances. United States v. Jagmohan, 909 F.2d 61, 65 (2d. Cir. 1990) (internal citations omitted). As there is nothing exceptional about the defendants employment history other than the multi-million theft that he devised and executed, there is no ground for departure. The defendants work history, of stealing from his victim-investors for over nine-plus years -- as he himself has admitted -- is hardly an indication of the exceptional or extraordinary

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 8 of 26

history that the Defendant would need to establish in order to satisfy the requirements established by the Second Circuit precedent. Jagmohan, 909 F.2d at 65. D. Defendant is Not Entitled to a Departure on the Other Grounds Advanced

Loles also argues for a departure based on a collection of other arguments including that he has lost friendships, has gotten divorced, has been incarcerated since his arrest, and may suffer humiliation in the press or on the internet. None of these arguments support the granting of a departure. First, the fact that he lost friendships and has been ostracized from his church community when he stole money from his friends and his church is merely the natural result of stealing money from friends and from the church at which you once practiced. Second, the fact that he has not had direct contact with his family and may be having marital difficulties or a divorce, while unfortunate, is again not uncommon given that he lied to his family, has committed a serious crime, and will spend many years in jail. In this regard, the Guidelines are instructive on the issue of family responsibilities, and provide that family ties and responsibilities are not ordinarily relevant in determining whether a departure may be warranted. U.S.S.G. 5H1.6. As the Second Circuit has articulated, consideration of family circumstances is discouraged as many defendants shoulder responsibilities to their families . . . disruption of the defendants life, and the concomitant difficulties for those who depend on the defendant are inherent in the punishment of incarceration. United States v. Johnson, 946 F.2d 124, 128 (2d Cir. 1992). Third, the fact that he was deemed a danger to the community or a possible flight risk and has been detained since his arrest is also not a reason to depart downward. While the Second Circuit has held that conditions of pre-trial confinement may in some instances be severe enough

8

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 9 of 26

to take a case outside the heartland of the applicable Guideline, United States v. Carty, 264 F.3d 191 (2d Cir. 2001), it is only where a case involves extreme abuse and unsafe and unsanitary prison conditions. See Carty, 264 F.3d at 193, 196-197 (remanding for consideration of departure request where defendant was subjected to cruel prison conditions including being held in a small cell with four other inmates, with no light, no running water, and no toilet, just a hole in the ground); United States v. Francis, 129 F. Supp. 2d 612 (S.D.N.Y. 2001) (downward departure granted where defendant made multiple complaints to the court during pretrial detention and the extensive factual record showed abuse and mistreatment suffered by defendant in a non-federal prison); United States v. Rodriguez, 213 F. Supp. 2d 1298 (M.D. Ala. 2002) (downward departure justified where defendant was raped by prison guard while awaiting sentencing, expressly limiting holding to factual circumstances of case). In this case, while Loles has spent pre-sentencing detention at Wyatt, there is no evidence that he has been treated any differently than any other inmate at this facility or that he has been the victim of physical or psychological abuse during his detention. Moreover, Loles has not cited any facts to support an argument that the conditions at Wyatt are in any way unduly harsh or substandard. In fact, it appears that he has been getting regular medical attention and has been treated well, even requesting extra mattresses, medicines, and the like. A departure in this case, based on the fact that Loles was held at Wyatt, would lead to a departure in every federal case in which the defendant is detained pre-trial. Loles will be given credit for time served and thus to give him additional time off his ultimate sentence would be tantamount to double credit for time served. Quite simply, defendants pre-sentencing detention does not take his case outside the Guidelines heartland and is insufficient to warrant a downward departure from the applicable Guidelines.

9

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 10 of 26

Loles also argues that he has suffered embarrassment on the internet and his reputation has been destroyed, forever and everywhere, (Def. Mem. Dkt. No. 164 at 10) and thus the punishment he has already suffered is sufficient. (Id.). This argument is without merit. It strains credulity to think that no further term of imprisonment is necessary to achieve the goals of sentencing including just punishment and specific and general deterrence in this case. Loles contends, in essence, that since white-collar felons such as himself are peculiarly sensitive to the ignominy of conviction and since he was embarrassed and humiliated and his reputation was hurt therefore, the conviction alone, without a significant prison sentence, is sufficient to achieve general deterrence. This argument should be rejected. First, recent history has shown that the risk of a felony conviction alone has not been sufficient to deter individuals who are tempted to put their personal financial interests above their legal and fiduciary duties to make full and truthful disclosures to their shareholders and the SEC. See Kroger, Enron, Fraud, and Securities Reform: an Enron Prosecutor's Perspective, 76 U. Colo. L. Rev. 57, 110 (Winter 2005) (noting that low sentences traditionally handed down to white-collar defendants under the Sentencing Guidelines failed to adequately deter corporate crime). Second, such an argument, at its core, relies on premises inimical to basic principles of equal application of the laws. According to this logic, one who is educated and highly regarded should not be sent to jail for committing the same crime that would justify a sentence of imprisonment for a less well-heeled and well-regarded defendant. This argument turns on its head the notion that from those who have the greatest advantages in life, the most is properly expected. The Court should reject the notion that white-collar criminals (like Loles) should be sentenced more lightly than the poor and powerless because, for the former, the embarrassment of

10

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 11 of 26

conviction alone (without any serious prison sentence) is more devastating than it would be for those who have enjoyed fewer advantages in life. Indeed, the author of a survey of academic research regarding the efficacy of criminal sanctions for white-collar crimes had this to say: White-collar crime is believed to be particularly amenable to deterrence due to its rational and profit-oriented motivation. In a conceptual analysis of the topic, Braithwaite and Geis observed that white-collar offenders are not committed to a lifestyle of illegality, are risk aversive, and have more to lose as a result of a criminal conviction than street offenders. Elsewhere Geis noted that [j]ail terms have a self-evident deterrent impact upon corporate officials, who belong to a social group that is exquisitely sensitive to status deprivation and censure. It is generally perceived that executives exhibit distress at the thought of being sentenced to incarceration: It results in hypertension, it causes heart attacks, it is very serious. Most judges and prosecutors view general deterrence as the one of the goals, if not the major purpose, in sentencing white-collar offenders. Punishment should serve to discourage others from committing similar offenses and jail or prison sentences, judges and scholars alike tend to believe, are particularly effective as a general deterrent.

Elizabeth Szockyj, Imprisoning White-Collar Criminals?, from Symposium: A Fork in the Road Build More Prisons or Develop New Strategies to Deal with Offenders, 23 S.Ill.U.L.J. 485, 492 (1999) (footnotes omitted); accord James J. Fishman, Enforcement of Securities Laws in the United Kingdom, 9 Int'l Tax & Bus. Law. 131, 170 (1991) (Though it may be small satisfaction to defrauded investors, incarcerating perpetrators of financial misdeeds serves an important deterrence to future violators. The certainty of enforcement and prison for white collar criminals is an effective deterrence.); Jennifer S. Recine, Note, Examination of the White Collar Crime Penalty Enhancements in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, 39 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1535 (Fall, 2002).

11

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 12 of 26

Thus, it follows that in direct contradiction to Loles argument, the fact that he is a white collar defendant means that the prison term should be stiffer and more significant to have the appropriate deterrent effect. III. The Need for Determining an Appropriate Sentence

As this Court is no doubt aware, in United States v. Crosby, 397 F.3d 103, the Second Circuit explained that, in light of United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005), district courts should engage in a three-step sentencing procedure. First, the district court must determine the

applicable Guidelines range, and in so doing, the sentencing judge will be entitled to find all of the facts that the Guidelines make relevant to the determination of a Guidelines sentence and all of the facts relevant to the determination of a non-Guidelines sentence. 112. Crosby, 397 F.3d at

Second, the district court should consider whether a departure from that Guidelines range Id. at 112. Third, the court must consider the Guidelines range, Aalong with all Id. at 112-13.

is appropriate.

of the factors listed in section 3553(a),@ and determine the sentence to impose.

The Second Circuit has instructed district judges to consider the Guidelines Afaithfully@ when sentencing. Crosby, 397 F.3d at 114. discretionary sentencing.@ ABooker did not signal a return to wholly

United States v. Rattoballi, 452 F.3d 127, 132 (2d Cir. 2006) (citing

Crosby, 397 F.3d at 113). The fact that the Sentencing Guidelines are no longer mandatory does not reduce them to Aa body of casual advice, to be consulted or overlooked at the whim of a sentencing judge.@ Crosby, 397 F.3d at 113. Because the Guidelines are Athe product of

careful study based on extensive empirical evidence derived from the review of thousands of individual sentencing decisions,@ Gall v. United States, 128 S. Ct. 586, 594 (2007), district courts must treat the Guidelines as the Astarting point and the initial benchmark@ in sentencing proceedings. Id. at 596; see also Rattoballi, 452 F.3d at 133 (the Guidelines A>cannot be called

12

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 13 of 26

just >another factor= in the statutory list, 18 U.S.C. ' 3553(a), because they are the only integration of the multiple factors and, with important exceptions, their calculations were based upon the actual sentences of many judges.=@) (quoting United States v. Jiminez-Beltre, 440 F.3d 514, 518 (1st Cir. 2006) (en banc); Kimbrough v. United States, 128 S. Ct. 558, 574 (2007). The Second Circuit has Arecognize[d] that in the overwhelming majority of cases, a Guidelines sentence will fall comfortably within the broad range of sentences that would be reasonable in the particular circumstances.@ United States v. Fernandez, 443 F.3d 19, 27 (2d

Cir. 2006); see also Kimbrough, 128 S. Ct. at 574 (AWe have accordingly recognized that, in the ordinary case, the Commission=s recommendation of a sentencing range will >reflect a rough approximation of sentences that might achieve ' 3553(a)=s objectives.=@)(quoting Rita v. United States, 127 S. Ct. 2456, 2465 (2007)); Rattoballi, 452 F.3d at 133 (AIn calibrating our review for reasonableness, we will continue to seek guidance from the considered judgment of the Sentencing Commission as expressed in the Sentencing Guidelines and authorized by Congress.@). Having addressed the Guidelines calculations and the fact that none of the sought after departures are applicable, the Court must now consider Section 3553(a) which provides that the sentencing Acourt shall impose a sentence sufficient, but not greater than necessary, to comply with the purposes set forth in paragraph (2) of this subsection,@ and which sets forth seven specific considerations: (1) (2) the nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant; the need for the sentence imposedC (A) to reflect the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense;

13

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 14 of 26

(B) (C) (D)

to afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct; to protect the public from further crimes of the defendant; and to provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment in the most effective manner;

(3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

the kinds of sentences available; the kinds of sentence and the sentencing range established [in the Sentencing Guidelines]; any pertinent policy statement [issued by the Sentencing Commission]; the need to avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants with similar records who have been found guilty of similar conduct; and the need to provide restitution to any victims of the offense.

For the reasons discussed above and the additional arguments set out below, the defendant=s conduct, weighed in view of the factors set forth in Section 3553(a), calls for a sentence of imprisonment that is significantly long. See 18 U.S.C. ' 3553(a)(4). A. The Nature and Circumstances of the Offense Calls for a Guideline Sentence

Defrauding any bank, corporate business, or entity out of more than $27 million is a very serious crime. However, defrauding real hard working people, including defrauding a church and fellow parishioners, a friend of many years (who described and treated Loles as a son), a Greek family comprised of a 19-year old young man and his widowed mother who Loles befriended after the passing of the father, as well as a number of other friends and business associates who believed he was running a successful business, and doing so over a nine-plus-year period is even that much more serious and egregious. Loles systematically lied to people B in many instances directly to their faces while at their homes, at the hospital bedsides of their loved ones, at church and church meetings, and at funerals and memorial services B and then flat-out stole their money. Moreover, as the scheme continued Loles adapted the scheme to take in larger and larger dollar amounts from families, friends, and business associates. Accordingly, it is the

14

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 15 of 26

Government=s position that the Court should sentence Loles to a term of imprisonment consistent with the seriousness, magnitude, and scope of the defendant=s conduct. Defense counsel seeks to compare this case to mortgage fraud where large institutions were defrauded of millions of dollars, and there are certainly some parallels in terms of financial devastation. However, the personal nature of this crime, in which victims knew Loles personally and trusted him, where their children played together, where they worshiped and mourned together, separates this case in kind from those like a Cendant or of a mortgage fraud. The victim impact is devastating. To state the obvious, the defendant engaged in a well-conceived and carefully calculated fraud scheme over the course of many years, which required setting up empty shell or sham companies, phony documents, lulling letters, fake tax documents, and actively lying to investors. The crime was orchestrated and committed using false documents, false letters, and by abusing the trust of friends, and it was committed for personal gain. It was committed so Loles could amuse himself racing cars (See Attachments A and B) and so he could buy a mansion. (See Attachments C and D). The illegal activity resulted in the loss of millions of dollars a huge sum of money. The bank records demonstrate that beginning as early as 2001, when he received investor funds, Loles almost immediately withdrew the stolen funds and spent them on items such as bogus interest payments, vacations, his large home, and his childrens tuition -- thus ensuring that the victims would never recover the stolen funds. By any measure B the seriousness of Loles illegal conduct, the amount of investor losses, and the impact on the victims and their families B a substantial prison sentence is warranted. In his sentencing memorandum the defendant states that Loles did not coldly and with careful calculation establish a fraudulent scheme with the intent to scam the gullible. (Def. Mem, Dkt.

15

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 16 of 26

No. 164 at 2). He argues that Loles right up until the end, believed that he possessed the resources by which he could fulfill the promises that he had made to his investors. (Id.) This is not the case. Any objective interpretation of the evidence developed in the investigation, especially the bogus account statements and fake interest payments, reveals that this assertion is false. Loles misled his investors from the very beginning, by falsely claiming that he could pay 7-8 % per year and that he had safe bonds: Arbitrage Bonds and Knightsbridge Bonds. Once he had successfully lured the victim-investors into his scheme via the fraudulent statements, he used the funds to pay off personal expenses and to keep the scheme going. When investors subsequently inquired into the status of their investments they were provided account statements, through which Loles continually lied and continued to defraud them. Over the years he continued expanding and perpetrating the scam by taking in more and more money. Perhaps one of the most glaring examples of Loles criminal behavior is demonstrated by his conduct in connection with two families that he defrauded, an elderly couple from Orange Connecticut one of whom told the Court that Loles was like a son to him and the other a Greek family half a world away, the son of whom told the FBI that Loles was like a second father to him. The parallels are striking and troubling. The abuse of this level of trust, to build such trust and use it for personal financial gain frankly shocks the conscious. His lying approached pathological. Loles took in millions from these two families with his chameleon like behavior. The entire scheme was rampant with fraud from the start. Having squandered millions on his car businesses and having only been able to sell a ten-percent share which was only accomplished by fraudulent inducement, Loles cannot seriously argue that he believed this business would make his investors whole. Considering the seriousness of this crime, adherence to the Sentencing Guidelines would not be an unjust punishment and would not be harsher than necessary to achieve

16

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 17 of 26

a just punishment. See United States v. Stitsky, 536 Fed.Appx. 98 (Oct 17, 2013) (affirming a sentence of 85 years where the loss amount was $23,152,235, more than 250 victims, sophisticated means, abuse of trust, and denying a Lauersen departure) (Summary Order Raggi, Droney, John F. Keenan). B. History and Characteristics of the Defendant

While this is Loless first conviction, it cannot be said that he was a hard working person who made a brief mistake. Loles has been a professional con-man since at least 2000 (if not earlier) having not held a legitimate job in many years As detailed in the report prepared for the Court by the probation office, Loles was educated at Purdue University as an engineer but has been self-employed with Apeiron Capital since 1995. (See PSR at & 95, 111-117). He has a very limited record of working, punching a time clock, and earning a pay-check. In fact, the records from the Social Security Administration and the IRS reflect little reported income during the last decade. There does not appear to be anything in his background, or his character and history that warrants a departure. The fact that he would take money from friends who trusted him and use the funds for his own personal amusement demonstrates his poor character. C. The Sentence Must Promote Respect for the Law.

The sentence in this case must reflect the seriousness of the offense committed promote respect for the rule of law and provide a message of deterrence to Loles himself and other defendants. The respect for the law and deterrence here must satisfy two goals. First, it must

deter all potential white-collar criminals who would consider defrauding investors. Second it must deter any and all defendants who would consider lying to the Court to try to game the system and get a better sentence.

17

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 18 of 26

As to the first, when investment promoters cannot be trusted to tell the truth, the entire marketplace suffers. A significant period of incarceration should be imposed in this case to demonstrate that those who defraud investors of their investment funds are punished with something more than a proverbial slap on the wrist and an order not to do it again. As to the second, the Court should send a strong message that perjury and false statements to the Court, to the U.S. Probation Officers and to the FBI, even during the sentencing process, will not be taken lightly. D. The Court Should Consider General Deterrence.

As already discussed, one of the factors the Court must consider in imposing sentence is the need for the sentence to afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct. 18 U.S.C. ' 3553(a)(2)(B). A significant prison sentence for such conduct can serve as a powerful deterrent against the commission of lucrative financial crimes by persons like Loles who have good educational backgrounds, professional licenses in the financial industry, and the ability to make plenty of money in a legitimate way yet turn to investment scams. Investment professionals and money managers in general, make daily decisions that affect their clients= investments. Unless such white-collar professionals truly understand that there are serious and certain consequences for their actions, the temptation to mislead investors and steal their investments cannot be tempered, let alone eliminated. It is only when these would-be con-men realize that similarly situated white collar criminals, such as Loles, go to jail for lengthy periods of time, that these persons will think twice before deciding to mislead investors and steal their funds. General deterrence serves an important function and as discussed above, works perhaps even more effectively than in the context of other types of criminal conduct, to prevent financial crimes. Similarly general deterrence must apply to the perjury aspect of the sentencing.

18

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 19 of 26

E.

The Need for Just Punishment and Protection of the Public Warrant

Finally, the goal of affording just punishment would not be served by a sentence significantly below the Guidelines range. In that regard, the need to avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants similarly situated is controlled in part by using the Guidelines as a starting point. Here the defendant has pleaded guilty to four counts of fraud. Any potential disparity is avoided by using the Guidelines as a very real starting point. When the Court looks at each of the specific offense characteristics and enhancements set forth in the Guidelines as applicable to Loles, it becomes clear that each one of them is seeking to address a separate ill or harm that can exist in financial fraud crimes. The fact that many of these enhancements are applicable to Loles perhaps explains how he was able to amass so much of his victims money. A prison sentence at or near the applicable Guidelines range is a just punishment that will: (a) promote respect for the law; (b) fairly punish the Defendant for his conduct; (c) send a message of general deterrence to prevent others from abusing their positions of trust; and (d) send a message of deterrence to fraudulent investment managers, that fraud is considered a serious crime by the Court and will be punished accordingly. V. Restitution Must be Made Part of the Sentence

In addition to the period of incarceration, the Defendant should be ordered to make full restitution to the victims of the fraud. The Mandatory Victims Restitution Act (AMVRA@), provides, in part, that in sentencing a defendant convicted of a felony committed through fraud or deceit, the court must order the defendant to pay restitution to any identifiable person directly and proximately harmed by the offense of conviction. See 18 U.S.C. ' 3663A(a)(2). The procedures to be followed in determining whether, and to what extent, to order restitution pursuant to the MVRA are those set out in 18 U.S.C. ' 3664. See id. ' 3663A(d).

19

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 20 of 26

Section 3664 provides that A[i]n each order of restitution, the court shall order restitution to each victim in the full amount of each victim's losses as determined by the court and without consideration of the economic circumstances of the defendant.@ added). Additionally, the defendant agreed, as part of his pleas to the following: AIn addition to the other penalties provided by law, the Court must also order that the defendant make restitution under 18 U.S.C. ' 3663A, and the Government reserves its right to seek restitution on behalf of victims of the defendant=s conduct consistent with the provisions of ' 3663A. (Plea Agreement at 4 (emphasis added). The parties also agreed that A[t]he defendant understands and agrees to make restitution to all the victims of his criminal conduct and understands that pursuant to 18 U.S.C. ' 3663A restitution is payable to all such victims and not merely to the victim or victims included in or referenced in the counts to which he agrees to plead guilty.@ 4-5. Plea Agreement at Id. ' 3664(f)(1)(A)(emphasis

Title 18 U.S.C. ' 3663A(a)(3) provides that: A[t]he court shall also order, if agreed to by

parties in the plea agreement, restitution to persons other than the victim of the offense.@ Here the defendant caused financial harm to approximately 700 victims, all of whom are entitled to restitution pursuant to 18 U.S.C. ' 3663A(a)(3). 1 To this end, The Government

calculates the restitution amount to be $27,198,025. (See Attachment AA@ to December 31, 2013

1

See, e.g., United States v. Thompson, 39 F.3d 1103, 1105 (10th Cir. 1994) (Awhen a defendant knowingly bargains to make full restitution in exchange for dismissal of other pending counts of an indictment, it should be presumed the bargain was made with its consequences in mind [and] it should be presumed a defendant in those circumstances considered its financial burden a fair exchange for the penal advantage gained@). The MVRA directs the Attorney General to ensure that Ain all plea agreements... consideration is given to requesting that the defendant provide full restitution to all victims of all charges contained in the indictment or information, without regard to the counts to which the defendant actually pleaded.@ 18 U.S.C. ' 3551 Mandatary Victim Restitution, Note (1).

20

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 21 of 26

filing). In ordering restitution, the Court should fix a schedule for payment of restitution, and in so doing, must consider the following statutory factors: (A) the financial resources and other assets of the defendant, including whether any of these assets are jointly controlled; (B) projected earnings and other income of the defendant; and (C) any financial obligations of the defendant; including obligations to dependents. 18 U.S.C. ' 3664(f)(2). Although the sentencing court need not make detailed factual findings on each factor, the record must disclose some affirmative act or statement allowing an inference that the district court in fact considered the defendant=s ability to pay. United States v. Lucien, 347 F.3d 45, 53 (2d Cir. 2003) (internal quotation marks omitted). If the Court intends to establish a schedule of periodic payments, it must do so expressly and clearly, as the failure to set forth such a schedule creates a presumption that the entire restitution amount is payable immediately. United States v. Nucci, 364 F.3d 419, 421 (2d Cir. 2004). Moreover, where the defendant has

the capacity for future employment at the conclusion of his term of imprisonment, the Court should properly consider his potential future earnings in fashioning an appropriate payment schedule. United States v. Lino, 327 F.3d 208, 210 (2d Cir. 2003) (An order of restitution, if That such a

fashioned on a delayed schedule, will call for payment at times far in the future.).

schedule necessarily involves some guesswork on the part of the Court regarding the defendants future income is no impediment to the Court making a reasonable prediction, based on information available at sentencing, regarding the amount of that income. Id.; United States v.

Ismail, 219 F.3d 76, 78 (2d Cir. 2000); United States v. Atkinson, 788 F.2d 900, 902 (2d Cir.

21

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 22 of 26

1986); see also United States v. Kinlock, 174 F.3d 297, 300 (2d Cir. 1999) (a defendants present financial situation does not eviscerate the district courts discretion to order restitution.). A. The Court Can Also Fashion A Payment Schedule In fashioning a payment schedule that properly takes into account the defendant=s personal expenses, the courts in this Circuit have frequently required the defendant to pay a percentage of his post-incarceration income as restitution. See United States v. Fiore, 381 F.3d

89, 98 n.9 (2d Cir. 2004) (sentencing court required the defendant to pay monthly installments following his release from incarceration; each monthly installment was based upon a formula which imposed a graduated percentage of his earned income based on the income amount); United States v. Walker, 353 F.3d 130, 132 (2d Cir. 2003) (sentencing court required the defendant to pay ten percent of his gross monthly earnings toward restitution during the three-year period of supervised release); United States v. Jaffe, 314 F.Supp.2d 216, 226 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) (requiring the defendant to pay the greater of $150,000 or fifteen percent of his post-tax annual income on a monthly basis). Accordingly, the Court shall order the defendant to make restitution to the victims of the fraud (see Attachment A to December 31, 2013 filing) and establish a payment schedule, designating when such payments should commence and how much the defendant should pay. In doing so, the Court should consider the defendant=s financial statement and further information supplied by defense counsel concerning the assets listed in the financial statement. See Hughey v. United States, 495 U.S. 411, 413; United States v. Germosen, 139 F.3d 120, 131 (2d Cir. 1998); United States v. Silkowski, 32 F.3d 682, 689 (2d Cir. 1994). There is no dispute that the Court should order restitution and accordingly a payment schedule should be set. The restitution portion of the judgment can provide for periodic

22

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 23 of 26

payments that extend beyond any term of imprisonment and term of supervision, until the debt has been paid in full. Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. ' 3613(b), a defendant=s obligation to pay

restitution does not expire until, at the earliest, twenty (20) years after the entry of judgment. See 18 U.S.C. ' 3613(b), 18 U.S.C. ' 3613(f) (making all provisions of 18 U.S.C. ' 3613 applicable to restitution). The Court may set a date certain for payment of the balance of the

restitution debt, but it is not required to do so. See 18 U.S.C. '' 3572(d)(1) and 3664(f)(3)(A). Moreover, as part of his conditions of supervised release the defendant can be required to make periodic payments. The end of the term of supervised release would in no way affect his The imposition

continuing obligation to pay the remaining restitution once supervision expires.

of restitution is a separate part of his sentence from any period of incarceration and a terms of supervised release. VI. The Ultimate Sentence to Be Imposed

As set forth in the multiple memoranda submitted to the Court, the Government contends that the facts are as presented by the Government including the fact that Loles made materially false statements to the Court. However, it bears repeating that if Loles did in fact have $14 million in Milbury holding upon which he could draw but which he did not call upon until approximately 2007, and when he did repatriate the money he failed to report it or pay a penny of taxes on it then he stands before the Court as an individual who was a millionaire 14 times over but did not pay any taxes on the money. In addition to running a multi-year Ponzi scheme and defrauding his friends a fellow Parishioners, when he did have enough money to repay everyone in 2007 he simply chose not to do so. He would stand before the Court a multi-millionaire 14 times over who still chose to steal the money from the St. Barbara Church Endowment fund and Building fund, including stealing scholarship money and money donated by hundreds of families

23

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 24 of 26

and collected by school children and then chose not to repay the money. He would stand before the Court a millionaire 14 times over who stole money from generations of hard working people. Loles stole retirement money, college tuition money, life insurance proceeds, and devastated an entire community simply so that he could run a street performance race car business and race Porsches, live like a king in a huge home with tennis courts a pool and a multi-car garage, and travel internationally, all while leaving his $14 million untouched in an account in London until 2007. When he did repatriate the funds he didnt pay back his victims but kept racing his fancy cars. What appears clear is that even after four years of incarceration Loles has still not yet learned his lesson. He still seeks to deceive, mislead and outright lie if he perceives it will benefit him in some way. Thus, no matter which version of the facts the Defendant choses to advance he must still be sentenced to a significantly long term of imprisonment befitting the crime and the defendant. Again a sentence at or above 360 months is not in appropriate, especially given the incredibly serious nature of the crime and the utter contempt that he has shown the Court and the judicial process.

24

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 25 of 26

II.

CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, those set forth in the prior Government=s Sentencing

Memoranda, and those advanced in open Court, the Government respectfully submits that, under the circumstances of this case the Defendants Offense level is a level 49. Moreover, under either calculation, the Court should not hesitate to give Defendant Loles a remarkably long period of incarceration and an order of restitution of over $27 million to the victims of his crimes.

Respectfully submitted, DEIRDRE M. DALY UNITED STATES ATTORNEY /S/ MICHAEL S. MCGARRY ASSISTANT U.S. ATTORNEY Federal Bar No. CT25713 157 Church Street, 23rd Floor New Haven, CT 06510 Tel.: (203) 821-3751 Fax: (203) 773-5378 Michael.McGarry@usdoj.gov

25

Case 3:10-cr-00237-AWT Document 166 Filed 02/23/14 Page 26 of 26

CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that on February 23, 2014 a copy of foregoing Government=s Sentencing Memorandum was filed electronically and served by hand on anyone unable to accept electronic filing. Notice of this filing will be sent by e-mail to all parties by operation of the Court=s electronic filing system or by mail to anyone unable to accept electronic filing as indicated on the Notice of Electronic Filing. Parties may access this filing through the Court=s CM/ECF System.

/S/ MICHAEL S. McGARRY ASSISTANT U.S. ATTORNEY

26

You might also like

- 2LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Sentencing MemoDocument403 pages2LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- LOLES Gregory AffidavitDocument9 pagesLOLES Gregory AffidavitHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Gibson's Bakery v. Oberlin College - Plaintiffs' Brief - Punitive Damage Caps Are UnconstitutionalDocument13 pagesGibson's Bakery v. Oberlin College - Plaintiffs' Brief - Punitive Damage Caps Are UnconstitutionalLegal InsurrectionNo ratings yet

- Federal Grand Jury Indictment of Gregory LolesDocument17 pagesFederal Grand Jury Indictment of Gregory LolesestannardNo ratings yet

- United States v. Yvonne Melendez-Carrion, Hilton Fernandez-Diamante, Luis Alfredo Colon Osorio, Filiberto Ojeda Rios, Orlando Gonzales Claudio, Elias Samuel Castro-Ramos and Juan Enrique Segarra Palmer, 804 F.2d 7, 2d Cir. (1986)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Yvonne Melendez-Carrion, Hilton Fernandez-Diamante, Luis Alfredo Colon Osorio, Filiberto Ojeda Rios, Orlando Gonzales Claudio, Elias Samuel Castro-Ramos and Juan Enrique Segarra Palmer, 804 F.2d 7, 2d Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument10 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NC Judicial College Jury Instructions Notebook MaterialsDocument22 pagesNC Judicial College Jury Instructions Notebook MaterialsdebbiNo ratings yet

- No. 98-2228, 215 F.3d 1140, 10th Cir. (2000)Document8 pagesNo. 98-2228, 215 F.3d 1140, 10th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dalton v. Capital Associated, 4th Cir. (2001)Document12 pagesDalton v. Capital Associated, 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Defense Motion To Exclude Evidence/arguments in Victor Hill TrialDocument10 pagesDefense Motion To Exclude Evidence/arguments in Victor Hill TrialJonathan RaymondNo ratings yet

- Evans Answer To Forfeiture ComplaintDocument22 pagesEvans Answer To Forfeiture ComplaintJames PilcherNo ratings yet

- 2014 House Bill 585 (Requested Revisions)Document5 pages2014 House Bill 585 (Requested Revisions)the kingfishNo ratings yet

- Janet Beasley v. Red Rock Financial Services, 4th Cir. (2014)Document13 pagesJanet Beasley v. Red Rock Financial Services, 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SUTZ V POWERS ET AL Judge Memorandum OpinionDocument4 pagesSUTZ V POWERS ET AL Judge Memorandum OpinionmikekvolpeNo ratings yet

- People v. Dekraai - Dismiss Death Penalty MotionDocument505 pagesPeople v. Dekraai - Dismiss Death Penalty MotionPeacockEsqNo ratings yet

- Hunt v. East Cleveland DecisionDocument10 pagesHunt v. East Cleveland DecisionWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- Kayla Giles Vs Delta Defense LLC and United Specialty Insurance CompanyDocument6 pagesKayla Giles Vs Delta Defense LLC and United Specialty Insurance CompanyThe Town TalkNo ratings yet

- Monty Grow IndictmentDocument23 pagesMonty Grow IndictmentDeadspinNo ratings yet

- Gibson's Bakery v. Oberlin College - Order Awarding Attoney's Fees and ExpensesDocument7 pagesGibson's Bakery v. Oberlin College - Order Awarding Attoney's Fees and ExpensesLegal Insurrection100% (1)

- Government Motion To Exclude Evidence/arguments in Victor Hill TrialDocument18 pagesGovernment Motion To Exclude Evidence/arguments in Victor Hill TrialJonathan RaymondNo ratings yet

- Bell PleaDocument13 pagesBell PleaJ RohrlichNo ratings yet

- Government's Supplemental Motion For Forfeiture and RestitutionDocument10 pagesGovernment's Supplemental Motion For Forfeiture and RestitutionThe Herald NewsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Makushamari Gozo, 4th Cir. (2015)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Makushamari Gozo, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- HU ComplaintDocument19 pagesHU ComplaintWJLA-TVNo ratings yet

- Yomade Aborishade - Statement of FactsDocument3 pagesYomade Aborishade - Statement of FactsEmily BabayNo ratings yet

- Order Releasing Mark T Pappas With ConditionsDocument3 pagesOrder Releasing Mark T Pappas With ConditionsghostgripNo ratings yet

- Abu Hamza Al Masri Opposition To Motion To Modify Order On Attorney CommunicationsDocument12 pagesAbu Hamza Al Masri Opposition To Motion To Modify Order On Attorney CommunicationsPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument18 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument18 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gibson's Bakery v. Oberlin College - Plaintiffs' Opposition To Motion For Directed VerdictDocument41 pagesGibson's Bakery v. Oberlin College - Plaintiffs' Opposition To Motion For Directed VerdictLegal Insurrection100% (1)

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument16 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Judge Neal Biggers Denies Zach Scruggs 2255 Motion To Set Aside Guilty PleaDocument44 pagesJudge Neal Biggers Denies Zach Scruggs 2255 Motion To Set Aside Guilty PleaRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- In The United States District Court Western District of Texas Waco DivisionDocument185 pagesIn The United States District Court Western District of Texas Waco DivisiontheconduitNo ratings yet

- Indictment and Interrogation of David Muino Suarez by The State Attorney's Office in Paraná, BrazilDocument22 pagesIndictment and Interrogation of David Muino Suarez by The State Attorney's Office in Paraná, BrazilThe Department of Official InformationNo ratings yet

- Rule 222 Disclosure Cook County5Document2 pagesRule 222 Disclosure Cook County5prosperini21759100% (1)

- Memorandum of Plea Agreement - U.S. v. John B. StancilDocument19 pagesMemorandum of Plea Agreement - U.S. v. John B. StancilIan LindNo ratings yet

- Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument4 pagesMotion For Summary JudgmentJoe DonahueNo ratings yet

- Penn Station Detention Lawsuit 2/4/20Document19 pagesPenn Station Detention Lawsuit 2/4/20BrendanNo ratings yet

- Jazmonique Strickland Arraignment, 10 A.m., Jan. 25, 2021Document7 pagesJazmonique Strickland Arraignment, 10 A.m., Jan. 25, 2021WWMTNo ratings yet

- Yanti Mike Greene Contempt OrderDocument17 pagesYanti Mike Greene Contempt OrderTony OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Patty Vs DEA LawsuitDocument26 pagesPatty Vs DEA LawsuitoyedaneNo ratings yet

- Frost Bribery Charges Letter To AUSA-1Document10 pagesFrost Bribery Charges Letter To AUSA-1Lee PedersonNo ratings yet

- Sentencing Memo Writing Sample (Redacted Vers)Document5 pagesSentencing Memo Writing Sample (Redacted Vers)nancyreatonNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Against Bexar County Small Business Assistance ProgramDocument21 pagesLawsuit Against Bexar County Small Business Assistance ProgramChris HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Anthony Vega-Cruz - Connecticut Police ShootingDocument14 pagesAnthony Vega-Cruz - Connecticut Police ShootingLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Bar Complaint - Scott Vincent, Kyle Daly, Leon CannizzaroDocument9 pagesBar Complaint - Scott Vincent, Kyle Daly, Leon CannizzaroThomas FramptonNo ratings yet

- May 15 2019 Organization Donation of Goods and Services AgreementDocument3 pagesMay 15 2019 Organization Donation of Goods and Services AgreementJon RalstonNo ratings yet

- Sayers Prosecution Sentencing MemorandumDocument21 pagesSayers Prosecution Sentencing MemorandumWXYZ-TV Channel 7 Detroit100% (1)

- Sroga v. City of Chicago, The Et Al, 1 - 12-Cv-09288, No. 24 (N.D.ill. Jun. 3, 2013)Document13 pagesSroga v. City of Chicago, The Et Al, 1 - 12-Cv-09288, No. 24 (N.D.ill. Jun. 3, 2013)Jim KNo ratings yet

- Abu Hamza Al Masri Wolf Notice of Compliance With SAMs AffirmationDocument27 pagesAbu Hamza Al Masri Wolf Notice of Compliance With SAMs AffirmationPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- United States of America, Appellant-Cross-Appellee v. Joseph J. Santopietro Paul R. Vitarelli, Perry A. Pisciotti, 166 F.3d 88, 2d Cir. (1999)Document13 pagesUnited States of America, Appellant-Cross-Appellee v. Joseph J. Santopietro Paul R. Vitarelli, Perry A. Pisciotti, 166 F.3d 88, 2d Cir. (1999)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument7 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hallas Sentencing MemorandumDocument17 pagesHallas Sentencing Memorandumndc_exposedNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Reynaldo Vargas Government's Sentencing MemorandumDocument6 pagesU.S. v. Reynaldo Vargas Government's Sentencing MemorandumKQED NewsNo ratings yet

- In The United States District Court For The Northern District of Illinois Eastern DivisionDocument30 pagesIn The United States District Court For The Northern District of Illinois Eastern DivisionTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Jim Nicholson v. Reta Cox, A-1, Incorporated, D/B/A A-1 Mobile Homes, 914 F.2d 248, 4th Cir. (1990)Document3 pagesJim Nicholson v. Reta Cox, A-1, Incorporated, D/B/A A-1 Mobile Homes, 914 F.2d 248, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dailin Pico Rodriguez, 11th Cir. (2012)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Dailin Pico Rodriguez, 11th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 17-12-03 RE04 21-09-17 EV Motion (4.16.2024 FILED)Document22 pages17-12-03 RE04 21-09-17 EV Motion (4.16.2024 FILED)Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- TBL ltr March 5Document26 pagesTBL ltr March 5Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- TBL Ltr ReprimandDocument5 pagesTBL Ltr ReprimandHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Pura Decision 230132re01-022124Document12 pagesPura Decision 230132re01-022124Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- National Weather Service 01122024 - Am - PublicDocument17 pagesNational Weather Service 01122024 - Am - PublicHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- PURA 2023 Annual ReportDocument129 pagesPURA 2023 Annual ReportHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- West Hartford Proposed budget 2024-2025Document472 pagesWest Hartford Proposed budget 2024-2025Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- 20240325143451Document2 pages20240325143451Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- Hunting, Fishing, And Trapping Fees 2024-R-0042Document4 pagesHunting, Fishing, And Trapping Fees 2024-R-0042Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Impacts of Hospital Consolidation in Ct 032624Document41 pagesAnalysis of Impacts of Hospital Consolidation in Ct 032624Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- 75 Center Street Summary Suspension SignedDocument3 pages75 Center Street Summary Suspension SignedHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Finn Dixon Herling Report On CSPDocument16 pagesFinn Dixon Herling Report On CSPRich KirbyNo ratings yet

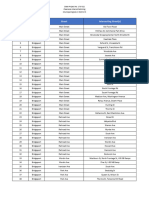

- Crime in Connecticut Annual Report 2022Document109 pagesCrime in Connecticut Annual Report 2022Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- CT State of Thebirds 2023Document13 pagesCT State of Thebirds 2023Helen Bennett100% (1)

- Commission Policy 205 RecruitmentHiringAdvancement Jan 9 2024Document4 pagesCommission Policy 205 RecruitmentHiringAdvancement Jan 9 2024Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- University of Connecticut Audit: 20230815 - FY2019,2020,2021Document50 pagesUniversity of Connecticut Audit: 20230815 - FY2019,2020,2021Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- South WindsorDocument24 pagesSouth WindsorHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- 2024 Budget 12.5.23Document1 page2024 Budget 12.5.23Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- District 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALDocument17 pagesDistrict 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Hartford CT Muni 110723Document2 pagesHartford CT Muni 110723Helen BennettNo ratings yet

- District 4 0174 0453 Project Locations FINALDocument6 pagesDistrict 4 0174 0453 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Be Jar Whistleblower DocumentsDocument292 pagesBe Jar Whistleblower DocumentsHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- District 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALDocument7 pagesDistrict 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Voices For Children Report 2023 FinalDocument29 pagesVoices For Children Report 2023 FinalHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- District 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALDocument17 pagesDistrict 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- PEZZOLO Melissa Govt Sentencing MemoDocument15 pagesPEZZOLO Melissa Govt Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- District 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALDocument7 pagesDistrict 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- PEZZOLO Melissa Sentencing MemoDocument12 pagesPEZZOLO Melissa Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Final West Haven Tier IV Report To GovernorDocument75 pagesFinal West Haven Tier IV Report To GovernorHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Hurley Employment Agreement - Final ExecutionDocument22 pagesHurley Employment Agreement - Final ExecutionHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Tax RTP May 2020Document35 pagesTax RTP May 2020KarthikNo ratings yet

- MID - Media Monitoring Report - July-2019 - English Version - OnlineDocument36 pagesMID - Media Monitoring Report - July-2019 - English Version - OnlineThetaungNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Power in The United KingdomDocument188 pagesNuclear Power in The United KingdomRita CahillNo ratings yet

- Democratization and StabilizationDocument2 pagesDemocratization and StabilizationAleah Jehan AbuatNo ratings yet

- Sirat AsriDocument58 pagesSirat AsriAbbasabbasiNo ratings yet

- Expert Opinion Under Indian Evidence ActDocument11 pagesExpert Opinion Under Indian Evidence ActmysticblissNo ratings yet

- Letter of Enquiry - 12Document7 pagesLetter of Enquiry - 12ashia firozNo ratings yet

- QO-D-7.1-3 Ver-4.0 - Withdrawal of Specification of ItemsDocument3 pagesQO-D-7.1-3 Ver-4.0 - Withdrawal of Specification of ItemsSaugata HalderNo ratings yet

- Marking Guide for Contract Administration ExamDocument7 pagesMarking Guide for Contract Administration Examრაქსშ საჰაNo ratings yet

- Quotation for 15KW solar system installationDocument3 pagesQuotation for 15KW solar system installationfatima naveedNo ratings yet

- Gorgeous Babe Skyy Black Enjoys Hardcore Outdoor Sex Big Black CockDocument1 pageGorgeous Babe Skyy Black Enjoys Hardcore Outdoor Sex Big Black CockLorena Sanchez 3No ratings yet

- STAMPF V TRIGG - OpinionDocument32 pagesSTAMPF V TRIGG - Opinionml07751No ratings yet

- Application For Schengen Visa: This Application Form Is FreeDocument2 pagesApplication For Schengen Visa: This Application Form Is FreeMonirul IslamNo ratings yet

- Guidelines on sick and vacation leaveDocument2 pagesGuidelines on sick and vacation leaveMyLz SabaLanNo ratings yet

- Wee vs. de CastroDocument3 pagesWee vs. de CastroJoseph MacalintalNo ratings yet

- Digbeth Residents Association - ConstitutionDocument3 pagesDigbeth Residents Association - ConstitutionNicky GetgoodNo ratings yet

- TL01 Behold Terra LibraDocument15 pagesTL01 Behold Terra LibraKeyProphet100% (1)

- Consti II NotesDocument108 pagesConsti II NotesVicky LlasosNo ratings yet

- WT ADMIT CARD STEPSDocument1 pageWT ADMIT CARD STEPSSonam ShahNo ratings yet

- Projector - Manual - 7075 Roockstone MiniDocument20 pagesProjector - Manual - 7075 Roockstone Mininauta007No ratings yet

- Explore the philosophical and political views on philanthropyDocument15 pagesExplore the philosophical and political views on philanthropykristokunsNo ratings yet

- EksmudDocument44 pagesEksmudKodo KawaNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Simple Interest: StarterDocument37 pages1.1 Simple Interest: Starterzhu qingNo ratings yet

- Ingeus Restart Scheme Participant Handbook Cwl-19july2021Document15 pagesIngeus Restart Scheme Participant Handbook Cwl-19july2021pp019136No ratings yet

- CH 12 Fraud and ErrorDocument28 pagesCH 12 Fraud and ErrorJoyce Anne GarduqueNo ratings yet

- Hacienda LuisitaDocument94 pagesHacienda LuisitanathNo ratings yet

- Major League Baseball v. CristDocument1 pageMajor League Baseball v. CristReid MurtaughNo ratings yet

- BISU COMELEC Requests Permission for Upcoming SSG ElectionDocument2 pagesBISU COMELEC Requests Permission for Upcoming SSG ElectionDanes GuhitingNo ratings yet

- Combination Resume SampleDocument2 pagesCombination Resume SampleDavid SavelaNo ratings yet

- Lc-2-5-Term ResultDocument44 pagesLc-2-5-Term Resultnaveen balwanNo ratings yet