Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Service of Notice - Section 138

Uploaded by

Sudeep SharmaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Service of Notice - Section 138

Uploaded by

Sudeep SharmaCopyright:

Available Formats

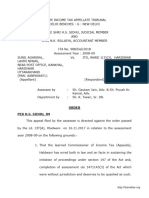

MANU/DE/0131/2009 Equivalent Citation: (2009)222CTR(Del)117, [2010]321ITR249(Delhi) IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI W.P. (C) 8768/2008 and CM No.

16842/2008 Decided On: 13.02.2009 Appellants: Mayawati Vs. Respondent: CIT (Central-I) and Ors. Hon'ble Judges: Vikramajit Sen and Rajiv Shakdher, JJ. Counsels: For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Harish N. Salve, S.C. Mishra, Sr. Advs., Shail Kumar Dwivedi, Praveen Chauhan, Rakesh Gupta, Meenakshi Grover and Shashwat Kumar, Advs For Respondents/Defendant: R.D. Chaudhary and Rani, Advs. Subject: Direct Taxation Catch Words Mentioned IN Acts/Rules/Orders: Income Tax Act - Sections 138, 139, 139(1), 142(1), 143(2), 143(3), 147, 148 to 153, 153(2) and 163; Finance Act, 1996; Finance Act, 2002; General Clauses Act, 1897 - Section 27;Evidence Act - Section 114; Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881; Constitution of India - Article 226 Cases Referred: CIT v. Shanker Lal Ved Prakash (2008) 300 ITR 0243; CIT v. Jai Prakash Singh (1996) 219 ITR 0737; CIT v. Gyan Prakash Gupta (1987) 165 ITR 0501; R.K. Upadhyaya v. Shanabhai P. Patel (1987) 166 ITR 163; Banarsi Debi v. ITO (1964) 53 ITR 100; CIT v. Lallubhai Jogibhai (211) 1995 ITR 769 (High Court of Bombay; Dharampal Singh Rao v. Income Tax Officer (2004) 191 CTR (All) 158; CIT v. Lunar Diamonds Ltd. (2006) 281 ITR 1(Delhi); CIT v. Vardhman Estates (P) Ltd. (2006) 287 ITR 368 (Delhi); CIT v. Bhan Textiles (P) Ltd. (2006) 287 ITR 370;Haryana Acrylic Manufacturing Company v. The Commissioner of Income-Tax IV; GKN Driveshafts (India) Limited v. Income Tax Officer (2003) 1 SCC 72; Har Charan Singh v. Shiv Rani AIR 1981 SC 1284; C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammed (2007) 6 SCC 555; Jagdish Singh v. Natthu Singh (1992) 1 SCC 647 : AIR 1992 SC 1604; State of M.P. v. Hiralal (1996) 7 SCC 523;V. Raja Kumari v. P. Subbarama Naidu (2004) 8 SCC 774 : AIR 2005 SC 109 Citing Reference: CIT v. Shanker Lal Ved Prakash CIT v. Jai Prakash Singh Mentioned Mentioned Jolly, Sr. Standing Counsel, Paras 157(2009)DLT324,

CIT v. Gyan Prakash Gupta R.K. Upadhyaya v. Shanabhai P. Patel Banarsi Debi v. ITO CIT v. Lallubhai Jogibhai Dharampal Singh Rao v. Income Tax Officer CIT v. Lunar Diamonds Ltd. CIT v. Vardhman Estates (P) Ltd. CIT v. Bhan Textiles (P) Ltd. Haryana Acrylic Manufacturing Company v. The Commissioner of Income-Tax IV;

Discussed Discussed Mentioned Mentioned Mentioned Mentioned Mentioned Mentioned Discussed

GKN Driveshafts (India) Limited v. Income Tax Officer Discussed Har Charan Singh v. Shiv Rani C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammed Jagdish Singh v. Natthu Singh MANU/SC/0313/1992 State of M.P. v. Hiralal V. Raja Kumari v. P. Subbarama Naidu MANU/SC/0937/2004 Discussed Discussed Discussed Mentioned Discussed

Disposition: Petition dismissed Head Note: Income Tax Act, 1961 Reassessment - Notice under Section 148 Presumption as to service of notice-AO issued a notice dt. 25-3-2008 under Section 147/148 of the Act to the petitioner at her Delhi address, purely as a coincidence, the petitioner had dispatched a letter on the same date i.e. 25-3-2008 to the revenue, stating that since she had become the Chief Minister of the Uttar Pradesh State Legislative Council, she had shifted her residence to Lucknow, which should be taken as a record for service and of all correspondence in respect to income-tax proceedings. This letter was received in the office of the AO on 31-3-2008. Inspector of the revenue endeavoured to serve notice dt. 25-3-2008 on the petitioner on 29-3-2008 at her New Delhi residence, in the course of which he was informed that she had shifted her residence to Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh where the notice should now be delivered. It was in these circumstances that the AO dispatched the notice dated 25-3-2008 by speed post on 29-3-2008 to the said Lucknow address furnished to him. The petitioner declined to accept the notice - firstly at New Delhi, secondly at Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh and thirdly at another place in Lucknow. All three addresses belonged to the petitioner at the relevant time. Held: Under these circumstances, and as redirection of notice was officially informed by assessee, due service is presumed under Section 27 of General Clauses Act. No interference was called for. In stark contrast, Section 148/149 speaks only of the issuance of a notice under the preceding Section within a prescribed period. Section 149 of the IT Act does not mandate that such a notice must also be served on the assessee within the prescribed period. It had not been seriously contended that the notice under Section 149 must also be served within the period set down in that Section since the discussion centered upon Section 27 of the General Clauses Act, 1897 which specifies that service of such a notice would be presumed to be legally proper as it

would be deemed to have been delivered in the ordinary course at the correct address. Where a statute postulates the issuance of a notice and not its service, a fortiori the presumption of fiction of service must be drawn on the lines indicated in Section 27 of the General Clauses Act, 1897. [Para 6] The notice dated 25-3-2008 had been personally taken to C-1/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi where the Inspector was told to dispatch it to Property No, 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. There is no averment in the petition to the effect that on 29-3-2008 the petitioner was not in Delhi or that she would have gained knowledge of the contents of the notice unless it had been served upon her in Lucknow. In today's day and age, reaching even the remotest parts of the globe is possible within a day. Even if the petitioner was not in Delhi on 29-3-2008, she could have been informed almost instantaneously of the service of the notice even if she was in Lucknow. It is, therefore, a moot question that the petitioner must be deemed to have been served in New Delhi on 29-3-2008 itself since those were the premises allotted to her by the Government of India in her status as a Member of Parliament. This court does not have to give a definitive answer on this issue since it is the position of the revenue that the petitioner must be deemed to have been served in Lucknow on 2-4-2008. According to the revenue, the notice dated 25-32008 was dispatched to C-l/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi-110 003 by speed post on 29-3-2008. Court has perused the envelope and the postal receipt bears this statement to be correct. The court cannot but presume that the postman had visited Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh and was thereupon redirected to serve the notice at 5, Kalidas Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. [Para 12] It is evident, therefore, that the petitioner declined to accept the notice-firstly at C-l/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi-110 003, secondly at Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh and thirdly at 5, Kalidas Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. All three addresses belonged to the petitioner at the relevant time. [Para 11] Wherever service of a notice is essential or critical, experience shows that it is a most difficult task to achieve. It is for this reason that Section 27 of the General Clauses Act creates a statutory presumption to the effect that if a letter is properly addressed, it must be deemed to have been served. [Para 12] The petitioner has failed to disclose any grounds justifying the exercise of extraordinary jurisdiction vested in this court by virtue of Article 226 of the Constitution of India. [Para 16] Income Tax Act, 1961 Section 148 JUDGMENT Vikramajit Sen, J. 1. This Writ Petition assails the legality of proceedings initiated by the Respondents under Section 147 of the Income Tax Act (IT Act for short) on the premise that the Assessing Officer (hereinafter AO) has reason to believe that income of the Petitioner, chargeable to tax, has escaped assessment. In such an event, Section 148 of the IT Act requires the AO to serve the Petitioner with a Notice requiring her to furnish a Return of her income. It is mandated by Section 149 of the IT Act that this Notice must be issued within six years from the end of the relevant Assessment Year (which in this case is 2001-2002) since the income chargeable to tax, which has escaped assessment, amounts to or is likely to amount to Rupees one lakh or more for that year. The prayers in the Petition are for quashing (a) the Notice dated 25.3.2008 issued under Section 148 of the IT Act; (b) the Notices dated 25.6.2008 and 3.11.2008 issued under Section 142(1) of the IT Act; and (c) the Order dated 27.11.2008. 2. The factual sequence is short and uncontroverted. The AO had passed an Order on 24.3.2008 stating that he has reason to believe that the Petitioner had not declared full and true particulars of her income. On 25.3.2008, the CIT, Central Range-III, recorded the approval to this proposal for initiation of proceedings and issuance of notice under Section 148 of the IT Act. Accordingly, the AO has issued a Notice dated 25.3.2008 under Sections 147/148 of the IT Act to the Petitioner at her Delhi address, viz. C-1/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi - 110 003. Mr. Salve contends that, purely as a coincidence, the Petitioner had dispatched a letter dated 25.3.2008 to the Revenue, stating that since she has become the Chief Minister of the Uttar Pradesh State Legislative Council, she had shifted her residence to Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

which should be taken as a record for service and of all correspondence in respect to income-tax proceedings. This letter was received in the Office of the Deputy Commissioner (Income Tax), Circle-II, New Delhi (the AO) on 31.3.2008. 3. It is not controverted that an Inspector of the Revenue endeavoured to serve this Notice on the Petitioner on 29.3.2008 at her Humayun Road, New Delhi residence, in the course of which he was informed that she had shifted her residence to 3, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh where the Notice should now be delivered. It was in these circumstances that the said Inspector dispatched the Notice dated 25.3.2008 by Speed Post on 29.3.2008 to the said Lucknow address furnished to him. The original records have been produced and we have perused the postal receipt which substantiates the Report of the Inspector. It appears that the Petitioner's letter dated 25.3.2008, informing the Respondent of her concealed income which has escaped assessment, requires action under Sections 147/148 of the IT Act. 4. The relevant provisions of the IT Act are reproduced for facility of reference: 147. If the Assessing Officer has reason to believe that any income chargeable to tax has escaped assessment for any assessment year, he may, subject to the provisions of Sections 148 - 153, assess or reassess such income and also any other income chargeable to tax which has escaped assessment and which comes to his notice subsequently in the course of the proceedings under this section, or recompute the loss or the depreciation allowance or any other allowance, as the case may be, for the assessment year concerned (hereafter in this section and in Sections 148 - 153 referred to as the relevant assessment year): Provided that where an assessment under Sub-section (3) of Section 143 or this section has been made for the relevant assessment year, no action shall be taken under this section after the expiry of four years from the end of the relevant assessment year, unless any income chargeable to tax has escaped assessment for such assessment year by reason of the failure on the part of the assessee to make a return under Section 139 or in response to a notice issued under Sub-section (1) of Section 142 or Section 148or to disclose fully and truly all material facts necessary for his assessment, for that assessment year: Provided further that the Assessing Officer may assess or reassess such income, other than the income involving matters which are the subject-matter of any appeal, reference or revision, which is chargeable to tax and has escaped assessment. Explanation 1.-Production before the Assessing Officer of account books or other evidence from which material evidence could with due diligence have been discovered by the Assessing Officer will not necessarily amount to disclosure within the meaning of the foregoing proviso. Explanation 2.-For the purposes of this section, the following shall also be "deemed to be cases where income chargeable to tax has escaped assessment, namely:" (a) where no return of income has been furnished by the assessee although his total income or the total income of any other person in respect of which he is assessable under this Act during the previous year exceeded the maximum amount which is not chargeable to income-tax; (b) where a return of income has been furnished by the assessee but no assessment has been made and it is noticed by the Assessing Officer that the assessee has understated the income or has claimed excessive loss, deduction, allowance or relief in the return ; (c) where an assessment has been made, but(i) income chargeable to tax has been underassessed; or (ii) such income has been assessed at too low a rate; or

(iii) such income has been made the subject of excessive relief under this Act; or (iv) excessive loss or depreciation allowance or any other allowance under this Act has been computed. 148. (1) Before making the assessment, reassessment or recomputation under Section 147, the Assessing Officer shall serve on the assessee a notice requiring him to furnish within such period, as may be specified in the notice, a return of his income or the income of any other person in respect of which he is assessable under this Act during the previous year corresponding to the relevant assessment year, in the prescribed form and verified in the prescribed manner and setting forth such other particulars as may be prescribed; and the provisions of this Act shall, so far as may be, apply accordingly as if such return were a return required to be furnished under Section 139: Provided that in a case(a) where a return has been furnished during the period commencing on the 1st day of October, 1991 and ending on the 30th day of September, 2005 in response to a notice served under this section, and (b) subsequently a notice has been served under Sub-section (2) of Section 143 after the expiry of twelve months specified in the proviso to Subsection (2) of Section 143, as it stood immediately before the amendment of said Sub-section by the Finance Act, 2002 (20 of 2002) but before the expiry of the time limit for making the assessment, re-assessment or recomputation as specified in Sub-section (2) of Section 153, every such notice referred to in this Clause shall be deemed to be a valid notice: Provided further that in a case(a) where a return has been furnished during the period commencing on the 1st day of October, 1991 and ending on the 30th day of September, 2005, in response to a notice served under this section, and (b) subsequently a notice has been served under Clause (ii) of Sub-section (2) of Section 143 after the expiry of twelve months specified in the proviso to Clause (ii) of Sub-section (2) of Section 143, but before the expiry of the time limit for making the assessment, reassessment or recomputation as specified in Sub-section (2) of Section 153, every such notice referred to in this clause shall be deemed to be a valid notice. Explanation.-For the removal of doubts, it is hereby declared that nothing contained in the first proviso or the second proviso shall apply to any return which has been furnished on or after the 1st day of October, 2005 in response to a notice served under this section. (2) The Assessing Officer shall, before issuing any notice under this section, record his reasons for doing so. 149. (1) No notice under Section 148 shall be issued for the relevant assessment year,(a) if four years have elapsed from the end of the relevant assessment year, unless the case falls under Clause (b); (b) if four years, but not more than six years, have elapsed from the end of the relevant assessment year unless the income chargeable to tax which has escaped assessment amounts to or is likely to amount to one lakh rupees or more for that year. Explanation.-In determining income chargeable to tax which has escaped assessment for the purposes of this Sub-section, the provisions of Explanation 2 of Section 147 shall apply as they apply for the purposes of that section.

(2) The provisions of Sub-section (1) as to the issue of notice shall be subject to the provisions of Section 151. (3) If the person on whom a notice under Section 148 is to be served is a person treated as the agent of a non-resident under Section 163 and the assessment, reassessment or recomputation to be made in pursuance of the notice is to be made on him as the agent of such non-resident, the notice shall not be issued after the expiry of a period of two years from the end of the relevant assessment year. 5. On a plain reading of these Sections it is palpably plain that Section 148 of the IT Act enjoins that the AO must serve on the assessee a notice requiring him to furnish a Return of his income, in respect of which he/she is assessable under this Act during the previous year corresponding to the relevant assessment year. Firstly, the notice contemplated by this Section relates to the furnishing of a Return and not to the decision to initiate proceedings under Section 147 of the IT Act; secondly, the period of thirty days (omitted by the Finance Act, 1996) is with regard to the furnishing of the Return. 6. In stark contrast, Section 149 of the IT Act speaks only of the issuance of a notice under the preceding Section within a prescribed period. Section 149 of the IT Act does not mandate that such a notice must also be served on the assessee within the prescribed period. Speaking for the Division Bench of this Court, I had occasion to observe in CIT v. Shanker Lal Ved Prakash MANU/DE/9589/2006 : [2008]300ITR243(Delhi) the decision in CIT v. Jai Prakash Singh MANU/SC/0344/1996 : [1996]219ITR737(SC) to the effect that failure to serve a notice under Section 143(2) would not render the assessment as null and void but only as irregular. The decision of the Rajasthan High Court in CIT v. Gyan Prakash Gupta MANU/RH/0217/1985 opining that an assessment order completed without service of notice under Section 143(2) is not void ab initio and cannot be annulled was noted. Furthermore, from a reading of that Judgment, it is evident that it had not been seriously contended that the notice under Section 149 of the IT Act must also be served within the period set-down in that Section since the discussion centered upon Section 27 of the General Clauses Act, 1897 which specifies that service of such a notice would be presumed to be legally proper as it would be deemed to have been delivered in the ordinary course at the correct address. It had, inter alia, been expressed that: while there would be no justification for enlarging the period of limitation prescribed by the statute itself, we should also not lose sight of the fact that disadvantage or discomfort of the assessee is only that he has to explain the correctness and veracity of the Return filed by him. A reasonable balance of burden of proof must also, therefore, be maintained. In the facts and circumstances of the present case, we are satisfied that because notice was dispatched on August 25, 1998 and was duly addressed and stamped, the Department has succeeded in proving its service before August 31, 1998. On the other hand, the assessee has failed to prove a statement that he received the notice only on 1.9.1998. Where a statute postulates the issuance of a notice and not its service, a fortiori the presumption of fiction of service must be drawn on the lines indicated in Section 27 of the General Clauses Act, 1897. 7. To dispel any possible doubt, it would be of advantage to refer to R.K. Upadhyaya v. Shanabhai P. Patel MANU/SC/0369/1987 : [1987]166ITR163(SC) wherein it has been held that since the AO had issued a notice of reassessment under Section 147 by Registered Post on 31.3.1970, which notice was received by the assessee on 3.4.1970, nevertheless the notice was not barred by limitation and retained its legal efficacy. Their Lordships spoke thus: ...A clear distinction has been made out between "the issue of notice" and "service of notice" under the 1961 Act. Section 149 prescribes the period of limitation. It categorically prescribes that no notice under Section 148 shall be issued after the prescribed limitation has lapsed. Section 148(1) proves for service of notice as a condition precedent to making the order of assessment. Once a notice is issued within the period of limitation, jurisdiction becomes vested in the Income-tax Officer to proceed to reassess. The mandate of Section 148(1) is that reassessment

shall not be made until there has been service. The requirement of issue of notice is satisfied when a notice is actually issued. In this case, admittedly, the notice was issued within the prescribed period of limitation as March 31, 1970, was the last day of that period. Service under the new Act is not a condition precedent to conferment of jurisdiction on the Income-tax Officer to deal with the matter but it is a condition precedent to the making of the order of assessment. The High Court, in our opinion, lost sight of the distinction and under a wrong basis felt bound by the judgment in Banarsi Debi v. ITO MANU/SC/0105/1964 : [1964]53ITR100(SC) . As the Income-tax Officer had issued notice within limitation, the appeal is allowed and the order of the High Court is vacated. The Income-tax Officer shall now proceed to complete the assessment after complying with the requirement of law. Since there has been no appearance on behalf of the respondents, we make no orders for costs. 8. On the strength of this pronouncement similar results have been reached in CIT v. Lallubhai Jogibhai MANU/MH/0210/1994 : [1995]211ITR769(Bom) High Court of Bombay; Dharampal Singh Rao v. Income Tax Officer MANU/UP/0484/2004 : [2004]271ITR223(All) . Reference would be relevant to three decisions of Division Benches of this Court, viz. CIT v. Lunar Diamonds Ltd. MANU/IG/5039/2005; CIT v. Vardhman Estates (P) Ltd. MANU/DE/9256/2006 : [2006]287ITR368(Delhi) and CIT v. Bhan Textiles (P) Ltd. MANU/DE/9257/2006 : [2006]287ITR370(Delhi) . In the context of Section 143 of the IT Act it has been held that the words "issuance of notice" and "service of notice" are not synonymous and interchangeable and accordingly, the notice under this Section would lose all its legal efficacy if it had not been actually served on the assessee within the scheduled and stipulated time. In this dialectic, a fortiori, since the word "served" is conspicuous by its absence in Section 149, and the Legislature has deliberately used the word "issued", actual service within the period of four or six years specified in the Section, would not be critical. In fairness to Mr. Salve, his argument was that whilst it was not mandatory for the impugned Notice to have been actually served on the Petitioner before 31.3.2008, it could not have been left abandoned on the file. We are not convinced a bit by the argument of Mr. Jolly that the notice could be served at any time before the commencement of the proceedings under Section 142(1) of the IT Act. In the facts of the present case, after the first service in March/April, 2008, no further steps to issue the notice under Section 147 of the IT Act to the Petitioner were initiated, although notices under Section 142(1) appear to have been dispatched. The stand of the Revenue is short and simple, viz., that the Petitioner must be deemed to have been served with the Notice dated March 25, 2008. 9. Mr. Salve, learned Senior Counsel appearing for the Petitioner, has sought strong support from the decision of a Division Bench of this Court of which my esteemed brother, Rajiv Shakhdher, J. was a member, in Haryana Acrylic Manufacturing Company v. The Commissioner of Income-Tax IV, decided on 3.11.2008. Various issues had arisen in that case, none of which, in our opinion, are of any relevance to the determination of the questions which fall for determination by us. In Haryana Acrylic it had, inter alia, been opined that for Section 147to become operational it is essential that it should be alleged that escapement of income is a consequence of the assessee having failed to fully and truly disclose all material facts necessary for the comprehensive completion of the assessment. What had transpired in that case was that whilst the initiation of the proceedings by the AO for approval of the Commissioner of Income Tax mentioned the failure on the part of the Assessee to disclose fully and truly all material facts relating to the alleged accommodation entries, the "reasons" disclosed to the Assessee on its request merely mentioned those accommodation entries as being the foundation for the belief that income to the extent of Rupees 5,00,000/- had escaped assessment. The distinction between these two situations has been perspicuously emphasised and adumbrated. The finding was that a reason to believe, without the essential concomitant of it being a result of the failure of the assessee to fully and truly disclose all material facts, would render the reassessment under Sections 147/148 unsustainable. In order to overcome this difficulty, it has been argued on behalf of the Revenue that since the AO had duly recorded the failure on the part of the assessee to fully and truly disclose all material facts this notation should be acted upon and the reasons conveyed to the assessee which were predicated on the Commissioner's noting, should be ignored. The contention of the Revenue was that the assessee had been made aware of the opinion of the AO in the Counter Affidavit of the Revenue filed on 5.11.2007. It was in that context that it was observed in Haryana Acrylic that

six years had elapsed by that time. GKN Driveshafts (India) Limited v. Income Tax Officer (2003) 1 SCC 72 was applied to emphasise the fact that the reasons should have been furnished within a reasonable time. It was clarified that "where the notice has been issued within the said period of six years, but the reasons have not been furnished within that period, in our view, any proceedings pursuant thereto would be hit by the bar of limitation inasmuch as the issuance of the notice and the communication and furnishing of reasons go hand-in-hand. The expression "within a reasonable period of time" as used by the Supreme Court in GKN Driveshafts (supra) cannot be stretched to such an extent that it extends even beyond the six years stipulated in Section 149". The factual matrix in Haryana Acrylic is inapplicable to the sequence of events before us and, therefore, reliance by Mr. Salve to that decision is inapposite. 10. An important question is whether a noticee can insist that service must be effected upon him/her only at a specified address. It would be recalled that the Notice dated 25.3.2008 had been personally taken to C-1/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi where the Inspector was told to dispatch it to Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. There is no averment in the Petition to the effect that on 29.3.2008 the Petitioner was not in Delhi or that she would have gained knowledge of the contents of the Notice unless it had been served upon her in Lucknow. In today's day and age reaching even the remotest parts of the globe is possible within a day. Even if the Petitioner was not in Delhi on 29.3.2008, she could have been informed almost instantaneously of the service of the notice even if she was in Lucknow. It is, therefore, a moot question that the Petitioner must be deemed to have been served in New Delhi on 29.3.2008 itself since those were the premises allotted to her by the Government of India in her status as a Member of Parliament. We do not have to give a definitive answer on this issue since it is the position of the Revenue that the Petitioner must be deemed to have been served in Lucknow on 2.4.2008. According to the Revenue, the Notice dated 25.3.2008 was dispatched to C-1/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi - 110 003 by Speed Post on 29.3.2008. We have perused the envelope and the postal receipt bears this statement to be correct. The Court cannot but presume that the Postman had visited Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh and was thereupon redirected to serve the Notice at 5, Kalidas Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. The Postman's endorsements translated from Hindi reads thus: Stated that the notice was not received at the official residence of the Chief Minister, 5, Kalidas Marg and was told to deliver it at the earlier written address, that is, Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. 2.4.2008 11. It is evident, therefore, that the Petitioner declined to accept the notice - firstly at C- 1/11, Humayun Road, New Delhi - 110 003, secondly at Property No. 3, Survey No. 105, Nehru Road, Cantonment, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh and thirdly at 5, Kalidas Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. All three addresses belonged to the Petitioner at the relevant time. 12. Wherever service of a notice is essential or critical, experience shows that it is a most difficult task to achieve. It is for this reason that Section 27 of the General Clauses Act creates a statutory presumption to the effect that if a letter is properly addressed, it must be deemed to have been served. Section 27 reads as follows: 27. Meaning of service by post - Where any Central Act or Regulation made after the commencement of this Act authorises or requires any document to be served by post, whether the expression "serve" or either of the expressions "give" or "send" or any other expression is used, then, unless a different intention appears, the service shall be deemed to be effected by properly addressing, pre-paying and posting by registered post, a letter containing the document, and, unless the contrary is proved, to have been effected at the time at which the letter would be delivered in the ordinary course of post.

13. In this regard, the observations made in Har Charan Singh v. Shiv Rani AIR 1981 SC 1284 call for reproduction: 7. Section 27 of the General Clauses Act, 1897 deals with the topic- "Meaning of service by post" and says that where any Central Act or Regulation authorises or requires any document to be served by post, then unless a different intention appears, the service shall be deemed to be effected by properly addressing, prepaying and posting it by registered post, a letter containing the document, and unless the contrary is proved, to have been effected at the time at which the letter would be delivered in the ordinary course of post. The section thus raises a presumption of due service or proper service if the document sought to be served is sent by properly addressing, prepaying and posting by registered post to the addressee and such presumption is raised irrespective of whether any acknowledgment due is received from the addressee or not. It is obvious that when the section raises the presumption that the service shall be deemed to have been effected it means the addressee to whom the communication is sent must be taken to have known the contents of the document sought to be served upon him without anything more. Similar presumption is raised under illustration (f) to Section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act whereunder it is stated that the Court may presume that the common course of business has been followed in a particular case, that is to say, when a letter is sent by post by pre-paying and properly addressing it the same has been received by the addressee. Undoubtedly, the presumptions both under Section 27 of the General Clauses Act as well as under Section 114 of the Evidence Act are rebuttable but in the absence of proof to the contrary the presumption of proper service or effective service on the addressee would arise. In the instant case, additionally, there was positive evidence of the postman to the effect that the registered envelope was actually tendered by him to the appellant on November 10, 1966 but the appellant refused to accept. In other words, there was due service effected upon the appellant by refusal. In such circumstances, we are clearly of the view, that the High Court was right in coming to the conclusion that the appellant must be imputed with the knowledge of the contents of the notice which he refused to accept. It is impossible to accept the contention that when factually there was refusal to accept the notice on the part of the appellant he could not be visited with the knowledge of the contents of the registered notice because, in our view, the presumption raised under Section 27 of the General Clauses Act as well as under Section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act is one of proper or effective service which must mean service of everything that is contained in the notice. It is impossible to countenance the suggestion that before knowledge of the contents of the notice could be imputed the sealed envelope must be opened and read by the addressee or when the addressee happens to be an illiterate person the contents should be read over to him by the postman or someone else. Such things do not occur when the addressee is determined to decline to accept the sealed envelope. It would, therefore, be reasonable to hold that when service is effected by refusal of a postal communication the addressee must be imputed with the knowledge of the contents thereof and, in our view, this follows upon the presumptions that are raised under Section 27 of the General Clauses Act, 1897 and Section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act. 14. In C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammed MANU/SC/2263/2007 : 2007CriLJ3214 their Lordships' attention had been engaged on service of a notice under the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881. It was observed thus: 14. Section 27 gives rise to a presumption that service of notice has been effected when it is sent to the correct address by registered post. In view of the said presumption, when stating that a notice has been sent by registered post to the address of the drawer, it is unnecessary to further aver in the complaint that in spite of the return of the notice unserved, it is deemed to have been served or that the addressee is deemed to have knowledge of the notice. Unless and until the contrary is proved by the addressee, service of notice is deemed to have been effected at the time at which the letter would have been delivered in the ordinary course of business. This Court has already held that when a notice is sent by registered post and is returned with a postal endorsement "refused" or "not available in the house" or "house locked" or "shop closed" or "addressee not in station", due service has to be presumed. Vide Jagdish Singh v. Natthu Singh MANU/SC/0313/1992 : AIR1992SC1604 ; State of M.P. v. Hiralal MANU/SC/1388/1996 : [1996]1SCR480 and V. Raja Kumari v. P. Subbarama Naidu

MANU/SC/0937/2004 : 2005CriLJ127 . It is, therefore, manifest that in view of the presumption available under Section 27 of the Act, it is not necessary to aver in the complaint under Section 138 of the Act that service of notice was evaded by the accused or that the accused had a role to play in the return of the notice unserved 15. In Jagdish Singh v. Natthu Singh MANU/SC/0313/1992 : AIR1992SC1604 the Apex Court affirmed the conclusion of the High Court that the notice must be presumed to have been served on the addressee by virtue of the provisions of Section 27 of the General Clauses Act despite the fact that they were "not actually served on the appellant as they had come back unserved upon the alleged refusal by the appellant to accept them". Again, in V. Raja Kumari v. P. Subbarama Naidu MANU/SC/0937/2004 : 2005CriLJ127 it has been held that the principle incorporated in Section 27 of the General Clauses Act can profitably be imported in a case where the sendor has dispatched the notice by post with the correct address written on it. Then it can be deemed to have been served on the sendee unless he proves that it is not really served and that he was responsible for such non-service. Any other interpretation can lead to a very tenuous position as the drawer of the cheque who is liable to pay the amount would resort to the strategy of subterfuge by successfully avoiding the notice. 16. It is in view of this analysis that we have arrived at the firm conclusion that the Petitioner has failed to disclose any grounds justifying the exercise of extraordinary jurisdiction vested in this Court by virtue of Article 226 of the Constitution of India. 17. Writ Petition is dismissed. There shall, however, be no order as to costs.

Manupatra Information Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

MANU/AP/0651/2009 Equivalent Citation: 2010CriLJ1265 IN THE HIGH COURT OF ANDHRA PRADESH Criminal Revision Case Nos. 602 and 603 of 2009 Decided On: 30.10.2009 Appellants: D. Atchyutha Reddy Vs. Respondent: The State of A.P. and Anr. Hon'ble Judges: B. Seshasayana Reddy, J. Counsels: For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: C. Padmanabha Venkatram Reddy, Adv.

Reddy,

Sr. Counsel

and M.

For Respondents/Defendant: Additional Public Prosecutor (for No. 1) and N. Ratan Babu, Party-in-Person Subject: Banking Subject: Criminal Catch Words Mentioned IN Acts/Rules/Orders: Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 - Sections 27, 118, 138 and 139; Evidence Act Section 3; General Clauses Act, 1897 - Section 27; Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) - Sections 190, 200, 239, 251, 313, 427 and 482; Indian Penal Code, 1860 Sections 415 and 420 Case Note: Criminal - Conviction - Sections 138 of Negotiable Instrument Act and Section 420 of Indian Penal Code, 1960 - Accused was convicted for offence under Section 138 of N.I. Act and Section 420. IPC -- Hence, this Petition - Whether, guilt of accused was sufficiently proved - Held, concurrent finding was given by trial Court as well as appellate Court based on strong and reasonable evidence - The material brought on record clearly established that Complainant sent notice to correct address of Petitioner - Petitioner was issuing cheque after closing account indicates of his intention to deceive complainant from inception - Therefore, Trial Court as well as Appellate Court appreciated evidence brought on record in right perspective and found the petitioner/accused guilty for offence under Section 420, IPC - Therefore, by reducing the sentence of imprisonment imposed on Petitioner-accused for offences under Sections 138 of the N.I. Act and 420, IPC from two years to one year while maintaining the fine of Rs. 3,000/- in default to suffer simple imprisonment for three months for each of the offence - Petitions partly allowed Ratio Decidendi:

"When concurrent finding is given by trial Court as well as the appellate Court based on strong and reasonable evidence, no interference against the said finding is warranted in revision." Cases Referred: Hiten P. Dalai v. Bratindranath Banerjee 2001 CriLJ 4647; K.N. Beena v. Muniyappan and Anr. 2001 CriLJ 4745; K. Bhaskaran v. Sankaran Vaidhyan Balan 1999 CriLJ 4606; Maruti Udyog Ltd. v. Narendra and Ors. (1999) 1 SCC 113; Opts Marketing Private Ltd. and State of A.P. 2001 CriLJ 1489 (AP); K.S. Anto v. Union of India 1993 (76) Comp Cas 105; Sadshkumarv. Krishnagopal 1994 CriLJ 887 (Bom); State of Rajasthan v. Jaktab Sybdaran Cenebt Ubdystrues Ltd. 1996 DCR 633 SC; Gorantla Venkateswara Rao v. Koll Veera Raghava Rao 2006 CriLJ 1 (AP); Satish Jayantilal Shah v. Pankaj Mashruwala 1996 CriLJ 3099 (Guj); P.S.A. Thamotharan v. Dalmia Cements (B) Ltd. 2005 (1) DCR 85 (Mad); P.K. Manmadhan Kartha v. Sanjeev Raj and Anr. (2002) 7 SCC 150; C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammed and Anr. 2007 CriLJ 3214 (SC); Joseph Jose v. J. Baby, Puthuval Puravidom Poothoppu and Anr. 2002 CriLJ 4392 (Ker);M.M.T.C. Ltd. v. Medchal Chemicals (P) Ltd. 2002 CriLJ 266 (SC); Veralaxmi v. Syed Kasim Hussain 1962 (2) An. WR 137; K. Sudersanam v. S. Venkatarao AIR 1963 AP 442; Munagala Yadgiri v. Pittala Veeriah 1958 (1) Andh WR 413; Rajuladevula Srinu and Srinivas v. State of A.P. 2005 Andh LD (Cri) 38; State of A.P. v. Kanda Gopaludu (2005) 13 SCC 116 : AIR 2005 SC 3616; M. Ravi and Ors. v. Elumalai Chettiar 2006 CriLJ 1059 (Mad); Ashok Yeshwant Badave v. Surendra Madhavrao Nighojakar and Anr. (2001) 3 SCC 726 : 2001 CriLJ 1674; Bhola Nath Arora and Anr. v. State. 1982 CriLJ 1482 (Del); N. Devindrappa v. State of Karnataka (2007) 5 SCC 228 : 2007 CriLJ 2949; State of Madras v. A. Vaidyanatha Iyer AIR 1958 SC 61 : 1958 CriLJ 232; Krishna Janardhan Bhat v. Dattatraya G. Hegde 2008 AIR SCW 738 : 2008 CriLJ 1172; Rajendra B. Choudhari v. State of Maharashtra 2007 CriLJ 844; Gopal Dass v. The State AIR 1978 Delhi 138 : 1978 CriLJ 961; R.P. Kapur v. State of Punjab AIR 1960 SC 866 : 1960 CriLJ 1239; Palanioappa Gounder v. State of Tamil Nadu AIR 1977 SC 1323 : 1977 CriLJ 992 ORDER B. Seshasayana Reddy, J. 1. In both these revisions, the complainant and the accused are same. Both these Criminal Revision Cases relate to a cheque bearing No. 412223. dated 5-9-2004 issued by the accused. Therefore, they were heard together and are being disposed of this Common Judgment. 2. Background facts in a nutshell leading to filing of both these Criminal Revision Cases by the accused in C.C. Nos. 711 of 2006 and 35 of 2007 on the file of VII Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, at Hyderabad, are: a) Accused-D. Atchyutha Reddy is a film producer and director. According to the complainant-N. Ratan Babu, he and accused got acquaintance with each other for the past several years and they were family friends. The complainant contends that the accused borrowed Rs. 2.50 lakhs on 5-4-2003 in the presence of one M. Dayakar, who is known to both of them. The accused after receiving the amount issued a post-dated cheque for Rs. 2.50 Lakhs. The cheque is dated 5-9-2004. He presented the cheque in Andhra Bank, Saifabad Branch, for collection and the same came to be returned with an endorsement 'account closed'. The complainant issued a notice under Section 138(b) of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, (for short, 'the N.I. Act') to the accused to make good the amount covered under the cheque in question. The accused received the notice, but he did not respond. The accused stated to have closed the account on 24-1-2003 i.e. much earlier to the issuance of the cheque. Ex. P1 is the cheque. Ex. P2 is the cheque return memo. Ex. P3 is the office copy of the notice and Ex. P4 is the acknowledgment. The complainant filed the complaint on 5-11-2004 before Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate at Hyderabad, under Sections 190 and 200, Cr.P.C. for the offence under Section 138 of the N.I. Act. The learned Magistrate, after recording the sworn statement of the complainant, took cognizance of the offence under Section 138 of the N.I. Act, registering the case as C.C. No. 711 of 2006. On 14-3-2006, the complainant also

filed a complaint under Sections 190 and 200, Cr. PC. for the offence under Section 420. IPC. The learned Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, after recording the sworn statement of the complainant, took cognizance of the offence under Section 420, IPC registering the case as C.C. No. 35 of 2007. b) On appearance of the accused and on furnishing copies of documents, the learned Magistrate examined the accused under Section 251, Cr.P.C. in cheque bouncing case and under Section 239, Cr.P.C. in cheating case. The accused denied the accusations leveled against him and pleaded not guilty for the offences under Sections 138 of the N.I. Act and 420, IPC. c) In both the cases, the complainant examined himself as P.W. 1 and examined two more witnesses viz. M. Dayakar and Alapati Trinadha Rao as P.Ws. 2 and 3. P.W. 2 M. Dayakar claims to be present on the date of borrowing and also on the date on which the cheque in question came to be issued by the accused. N. Rajesh Babu, who is the son of the complainant is stated to have filled the contents of the cheque. According to the complainant, the accused read the contents of the cheque and confirmed the contents therein as correct and signed thereon and handed over the same to him with instructions to deposit the cheque on the date mentioned thereon. d) P.W. 3 is the Deputy Bank Manager of Andhra Bank, Nampally Branch, wherein the accused maintained the account bearing No. ASB 500009. According to him, the accused closed the account on 24-1-2003. Whereas, the complainant/P.W. 1 presented Ex. P1 cheque after the closure of the account. Ex. P2 is the cheque return memo. Ex. P5 is the copy of bank statement of account of the accused in respect of Account bearing No. ASB 500009. e) It is the plea of the accused that the complainant took blank undated promissory notes and cheques and made use of the blank promissory notes and cheques and filed various suits against him by the complainant, his wife-Rajeswari and his sonRajesh Babu and that there did not exist the relationship of creditor and debtor between him and the complainant. Except marking Certified Copy of the complaint in C.C. No. 35 of 2007 as Ex. D1, which is filed by the complainant, he did not choose to adduce any evidence. f) The learned Magistrate, considering material brought on record and on hearing the counsel appearing for the parties, found the accused guilty for the offences under Sections 138 of the N.I. Act and 420, IPC and convicted him accordingly and sentenced him to suffer rigorous imprisonment for two years and pay a fine of Rs. 3.000/- in default to suffer simple imprisonment for three months for each of the offences, by judgments dated 20-10-2008. Assailing the judgments of conviction and sentence passed in C.C. No. 711 of 2006 and C.C. No. 35 of 2007, the accused filed Crl. Appeal Nos. 337 and 338 of 2008 on the file of II Additional Metropolitan Sessions Judge at Hyderabad. The learned Additional Metropolitan Sessions Judge, on reappraisal of the evidence brought on record and on hearing the counsel appealing for the parties, did not find any valid ground to interfere with the conviction and sentence of the accused for the offences under Sections 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act and 420, IPC and accordingly, dismissed both the appeals, by judgments dated 30-3-2009. Hence, both these Criminal Revision Cases by the accused. More precisely, Crl. R. C. No. 602 of 2009 is directed against the judgment dated 30-3-2009 passed in Crl. A. No. 337 of 2008 and whereas, Crl. R.C. 603 of 2009 is directed against the judgment dated 30-3-2009 passed in Crl. A. No. 338 of 2008. 3. Heard Sri. C. Padmanabha Reddy, Learned Senior Counsel appearing for the petitioner/accused and the 2nd respondent-party in person. 4. Learned Senior Counsel submits that the trial Court as well as the lower appellate Court misread the provisions of Sections 118 and 139 of the N. I, Act and thereby conclusions arrived at by both the Courts below are unsustainable. In elaborating his arguments, learned senior counsel contended that there is no presumption as to the existence of debt and, therefore, once the petitioner denies the very existence of debt, initially burden lies on the complainant to prove the existence of debt as on the date of issuance of the cheque in question. Learned

Senior Counsel would also contend that as On 5-4-2003, the date of issuance of the cheque in question, there were various amounts totaling Rs. 15.00,000/- allegedly due to the son and wife of 2nd respondent-complainant and in which case the version of 2nd respondent-complainant and in which case the version of 2nd respondent complainant that he had lent Rs. 2,50,000/- as a hand loan on 5-42003 is highly improbable and unbelievable. A further contention has been raised that P.W. 2 is a stock witness on behalf of 2nd respondent-complainant in all the cases to speak of lending money by 2nd respondent-complainant as well as issuing cheques by the petitioner accused and, therefore, no credence could be given to his testimony and once his testimony is discarded, there is no other evidence to support the version of 2nd respondent-complainant that he lent money to the petitioner-accused on 5-4-2003. The lending of money by 2nd respondentcomplainant to the petitioner-accused in the given facts and circumstances, is highly doubtful in which case the initial burden with regard to existence of debt stands unproved and the result of which makes the provisions of Sections 118 and 139 of the N.I. Act inapplicable. Even otherwise the presumptions under Sections 118 and 139 of the N. I. Act available in favour of the 2nd respondent-complainant have been rebutted by the petitioner-accused through several circumstances brought out in the evidence of P.Ws. 1 and 2. 5. Learned Senior Counsel also contended that some of the suits filed by the wife and son of 1st respondent ended in dismissal on the ground of the suit pro-notes being not supported by consideration and the dismissal of the said suits lends support to the circumstances brought out by the petitioner in the evidence of P.Ws. 1 and 2 and in which case the conviction and sentence of the petitioner-accused under Section 138 of the N. I. Act and Sec, 420 of IPC is liable to be set aside. Learned Senior Counsel placed on record the photostat copies of the judgments passed in O.S. Nos. 1535 of 2006, 1133 of 2005, 2378 of 2003, 1134 of 2005 and 2277 of 2003. 6. As seen from the photostat copies of the judgments, suits filed by N. Rajesh Babu, son of 2nd respondent in O. S. Nos. 1535 of 2006, 1134 of 2005 and 2277 of 2003 and the suits filed by N. Rajeshwari. wife of 2nd respondent being O. S. Nos. 1133 of 2005 and 2378 of 2003 on the file of VII Additional Senior Civil Judge, FTC, CCC, Hyderabad ended in dismissal. 7. Learned Senior counsel took me to the evidence of P.Ws. 1 and 2 in great detail to convince that the presence of P.W. 2 at the time of lending as well as issuance of the cheque is highly unbelievable. 8. The 2nd respondent contends that the trial Court as well as the appellate Court considered the evidence brought on record in right perspective and found the petitioner-accused guilty for the offence under Section 138 of the N. I. Act and Section 420 of IPC. He also contended that there is no consistency in the defence of the petitioner and that itself is sufficient to infer that he failed to rebut the presumptions under Sections 118 and 139 of the N. I. Act. The 2nd respondent took me to the plea advanced by the petitioner in the quash petitions and suggestions put to P.W. 1 in the cross -examination and the statements of the petitioner under Section 313, Cr.P.C. to convince that there is no consistency in the plea advanced by the petitioner. He also cited innumerable decisions of the Supreme Court, this Court and various other High Courts on the aspect of presumptions under Sections 118 and 139 of the N. I. Act. He would also submit that the very fact of issuance of the cheque after the account had been closed indicates his fraudulent intention from the inception and that itself is sufficient to sustain the conviction of the petitioner for the offence under Section 420, IPC. The decisions cited by the 2nd respondent-complainant are: (1) Hiten P. Dalai v. Bratindranath Banerjee MANU/SC/0359/2001 : 2001 CriLJ 4647 (2) K.N. Beena v. Muniyappan and Anr. MANU/SC/0661/2001 : 2001 CriLJ 4745 (3) K. Bhaskaran v. Sankaran Vaidhyan Balan MANU/SC/0625/1999 : 1999 CriLJ 4606

(4) Maruti Udyog Ltd. v. Narendra and Ors. MANU/SC/0803/1999 : (1999) 1 SCC 113 (5) Opts Marketing Private Ltd. and State of A.P. MANU/AP/0119/2001 : 2001 CriLJ 1489 (AP) (6) K.S. Anto v. Union of India 1993 (76) Comp Cas 105 (7) Sadshkumarv. Krishnagopal MANU/MH/0142/1993 : 1994 CriLJ 887 (Bom) (8) State of Rajasthan v. Jaktab Sybdaran Cenebt Ubdystrues Ltd. 1996 DCR 633 SC (9) Gorantla Venkateswara Rao v. Koll Veera Raghava Rao MANU/AP/0865/2005 : 2006 Cri LJ 1 (AP) (10) Satish Jayantilal Shah v. Pankaj Mashruwala MANU/GJ/0013/1996 : 1996 CriLJ 3099 (Guj) (11) P.S.A. Thamotharan v. Dalmia Cements (B) Ltd. 2005 (1) DCR 85 (Mad) (12) P.K. Manmadhan Kartha v. Sanjeev Raj and Anr. MANU/SC/0732/2002 : (2002) 7 SCC 150 (13) C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammed and Anr. MANU/SC/2263/2007 : 2007 CriLJ 3214 (SC) (14) Joseph Jose v. J. Baby, Puthuval Anr. MANU/KE/0469/2002 : 2002 CriLJ 4392 (Ker) Puravidom Poothoppu and

(15) M.M.T.C. Ltd. v. Medchal Chemicals (P) Ltd. MANU/SC/0728/2001 : 2002 CriLJ 266 (SC) (16) Veralaxmi v. Syed Kasim Hussain 1962 (2) An. WR 137 (17) K. Sudersanam v. S. Venkatarao MANU/AP/0186/1963 : AIR 1963 AP 442 (18) Munagala Yadgiri v. Pittala Veeriah 1958 (1) AWR 413. (19) Rajuladevula Srinu and Srinivas v. State of A.P. 2005 ALD (Cri) 38 (20) State of A.P. v. Kanda Gopaludu MANU/SC/2468/2005 : (2005) 13 SCC 116 : AIR 2005 SC 3616 (21) M. Ravi and Ors. v. Elumalai Chettiar MANU/TN/0687/2005 : 2006 CriLJ 1059 (Mad) (22) Ashok Yeshwant Badave v. Surendra Madhavrao Nighojakar Anr. MANU/SC/0170/2001 : (2001) 3 SCC 726 : 2001 CriLJ 1674 and

(23) Bhola Nath Arora and Anr. v. State. MANU/DE/0208/1982 : 1982 CriLJ 1482 (Del) (24) N. Devindrappa v. State of Karnataka MANU/SC/7619/2007 : (2007) 5 SCC 228 : 2007 CriLJ 2949. 9. Section 138 of N. I. Act reads as under: Section 138 Dishonour of cheque for insufficiency, etc., of funds in the account Where any cheque drawn by a person on an account maintained by him with a banker for payment of any amount of money to another person from out of that account for the discharge, in whole or in part of any debt or other liability, is returned by the bank unpaid, either because of the amount of money standing to

the credit of that account is insufficient to honour the cheque or that it exceeds the amount arranged to be paid from that account by an agreement made with that bank, such person shall be deemed to have committed an offence and shall, without prejudice to any other provision of this Act, be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years or with fine which may extend to twice the amount of the cheque or with both. Provided that nothing contained in this section shall apply unless(a) the cheque has been presented to the bank within a period of six months from the date on which it was drawn or within the period of its validity, whichever is earlier. (b) the payee or the holder in due course of the cheque, as the case may be, makes a demand for the payment of the said amount of money by giving a notice, in writing, to the drawer of the cheque, within thirty days of the receipt of information by him from the bank regarding the return of the cheque as unpaid; and (c) the drawer of such cheque fails to make the payment of the said amount of money to the payee or, as the case may be, to the holder in due course of the cheque, within fifteen days of the receipt of the said notice. Explanation - For the purposes of this section, "debt or other liability" means a legally enforceable debt or other liability. 10. Section 138 of the N.I. Act has three ingredients, viz. (I) that there is a legally enforceable debt; (ii) that the cheque was drawn from the account of bank for discharge in whole or in part of any debt or other liability which pre-supposes a legally enforceable debt; and (iii) that the cheque so issued had been returned due to insufficiency of funds. The proviso appended to the said section provides for compliance of legal requirements before a complain petition can be acted upon by a Court of law. 'Section 139 of the Act merely raises a presumption in regard to the second aspect of the matter. Existence of legally recoverable debt is not a matter of presumption under Section 139 of the N. I. Act. It merely raises a presumption in favour of a holder of the cheque that the same has been issued for discharge of any debt or other liability. An accused for discharging the burden of proof placed upon him under a statute need not examine himself. He may discharge his burden on the basis of the materials already brought on records. An accused has a constitutional right to maintain silence. Standard of proof on the part of an accused and that of the prosecution in a criminal case is different. 11. The N. I. Act contains provisions raising presumptions as regards the negotiable instruments under Section 118(a) of the Act as also under Section 139 thereof. The said presumptions are rebuttable. Whether the presumption rebutted or not would depend upon the facts and circumstances of each case. The Supreme Court clearly laid down in catena of decisions that the standard of proof in discharge of the burden in terms of Sections 118 and 139 of the N.I. Act being the preponderance of a probability, the inference thereof can be drawn not only from the material brought on record but also from the reference to the circumstances upon which the accused relied upon. The burden to rebut the presumptions on the accused is not as high as that of the prosecution. 12. Under Section 118, unless the contrary is proved, it is to be presumed that the Negotiable Instrument (including a cheque) had been made or drawn for consideration. Under Section 139 the Court has to presume, unless the contrary was proved, that the holder of the cheque received the cheque for discharge, in whole or in part of a debt or liability. Thus, in complaints under Section 138, the Court has to presume that the cheque had been issued for a debt or liability. This presumption is rebuttable. However, the burden of proving that a cheque had not been issued for a debt or liability is on the accused. The Supreme Court in Hiten P. Dalai v. Bratindranath Banerjee MANU/SC/0359/2001 : 2001 CriLJ 4647 (supra), while dealing with sections 138 and 139 of N.I. Act held that whenever a cheque was issued to the complainant for a specific amount, there is a presumption that it is towards discharge of legally enforceable debt. In the event of dispute, the burden

is on the accused to prove that there is no subsisting liability as on the date of issuing of cheque and the proof must be sufficient to rebut the presumption and mere explanation is not sufficient. The Supreme Court further held as follows: (20) The appellant's submission that the cheques were not drawn for the "discharge in whole or in part of any debt or other liability' is answered by the third presumption available to the Banks under Section 139 of the Negotiable Instruments Act. This section provides that "it shall be presumed, unless the contrary is proved, that the holder of a cheque received the cheque, of the nature referred to in Section 138 for the discharge, in whole or in part, of any debt or other liability." The effect of these presumptions is to place the evidential burden on the appellant of proving that the cheque was not received by the Bank towards the discharge of any liability. (21) Because both Sections 138 and 139 require that the Court "shall presume" the liability of the drawer of the cheques for the amounts for which the cheques are drawn, as noted in State of Madras v. A. Vaidyanatha Iyer MANU/SC/0108/1957 : AIR 1958 SC 61 : 1958 CriLJ 232 it is obligatory on the Court to raise this presumption in every case where the factual basis for the raising of the presumption had been established. "It introduced an exception to the general rule as to the burden of proof in criminal cases and shifts the onus on to the accused" (ibid). Such a presumption is a presumption of law, as distinguished from a presumption of fact which describes provisions by which the Court "may presume" a certain state of affairs. Presumptions are rules of evidence and do not conflict with the presumption of innocence, because by the latter all that is meant is that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against the accused beyond reasonable doubt. The obligation on the prosecution may be discharged with the help of presumptions of law or fact unless the accused adduces evidence showing the reasonable possibility of the non-existence of the presumed fact. (22) In other words, provided the facts required to form the basis of a presumption of law exists, no discretion is left with the Court but to draw the statutory conclusion, but this does not preclude the person against whom the presumption is drawn from rebutting it and proving the contrary. A fact is said to be proved when, "after considering the matters before it the Court either believes it to exist or considers its existence so probable that a prudent man ought, under the circumstances of the particular case, to act upon the supposition that it exists". Section 3 : Evidence Act. Therefore, the rebuttal does not have to be conclusively established but such evidence must be adduced before the Court in support of the defence that the Court must either believe the defence to exist or consider its existence to be reasonably probable, the standard of reasonability being that of the "prudent man." The above referred decision has been referred to by the Supreme Court in subsequent decision in K.N. Beena v. Muniyappam MANU/SC/0661/2001 : 2001 CriLJ 4745 (supra). 13. I do not wish to burden the judgment by referring to the propositions of law laid down in the cases cited by 2nd respondent-complainant. It is suffice to refer the judgment of the Supreme Court in Krishna Janardhan Bhat v. Dattatraya G. Hegde MANU/SC/0503/2008 : 2008 AIR SCW 738 : 2008 CriLJ 1172 wherein after referring to various earlier judgments is observed as under: (33) We are not oblivious of the fact that the said provision has been inserted to regulate the growing business, trade, commerce and industrial activities of the country and the strict liability to promote greater vigilance in financial matters and to safeguard the faith of the creditor in the drawer of the cheque which is essential to the economic life of a developing country like India. This, however, shall not mean that the Courts shall put a blind eye to the ground realities. Statute mandates raising of presumption but it slops at that. It does not say how presumption drawn should be held to have rebutted. Other important principles of legal jurisprudence, namely presumption of innocence as human rights and the doctrine of reverse burden introduced by Section 139 should be delicately balanced. Such balancing acts, indisputably would largely depend upon the factual matrix of each case, the materials brought on record and having regard to legal principles governing the same.

14. There is obligation on the part of the Court to raise the presumptions under Sections 118 and 139 of the N.I. Act in every case where the factual basis for raising of the presumption had been established. 15. It is well settled that a notice returned with endorsement 'unclaimed' by the address can be presumed to have been served on him. In this connection, a reference to Section 27 of the General Clauses Act will be useful. The section reads as under: 27. Meaning of service by post : Where any Central Act or Regulation made after the commencement of this Act authorizes or requires any document to be served by post, whether the expression "serve" or either of the expressions "give" or "send" or any other expression is used, then, unless a different intention appeal's, the service shall be deemed to be effected by properly addressing, pre-paying and posting by registered post, a letter containing the document, and unless the contrary is proved, to have been effected at the time at which the letter would be delivered in the ordinary course of post. A similar question came up for consideration before the Supreme Court in K. Bhaskaran v. Sankaran Vaidhyan Balan MANU/SC/0625/1999 : 1999 CriLJ 4606 (supra), wherein it has been held as under: (24) No doubt Section 138 of the Act does not require that the notice should be given only by "post". Nonetheless the principle incorporated in Section 27 (quoted above) can profitably be imported in a case where the sender has despatched the notice by post with the correct address written on it. Then it can be deemed to have been served on the sendee unless he proves that it was not really served and that he was not : responsible for such non-service. Any other interpretation can lead to a very tenuous position as the drawer of the cheque who is liable to pay the amount would resort to the strategy of subterfuge by successfully avoiding the notice. (25) Thus, when a notice is returned by the sendee as unclaimed such date would be the commencing date in reckoning the period of 15 days contemplated in Clause (d) to the proviso of Section 138 of the Act. Of course such reckoning would be without prejudice to the right of the drawer of the cheque to show that he had no knowledge that the notice was brought to his address. In the present case the accused did not even attempt to discharge the burden to rebut the aforesaid presumption. 16. A question came up for consideration before this Court, whether the body of the cheque was required to be in the hand writing of the maker of it. In Gorantla Venkateswara Rao's case 2006 CriLJ 1 (supra), a learned single Judge of this Court after a detailed survey of various decisions of this Court has held that the legal position on this aspect is very clear that the body of the cheque need not necessarily be written by the accused and it can be in the handwriting of anybody else or typed on a type machine, so long as the accused does not dispute the genuineness of the signature on the cheque. What is material is signature of drawer or maker and not the body writing, hence, the dispute relating to body writing has no significance. It is not mandatory and no law prescribes that the body of the cheque should also be written by the signatory to the cheque. A cheque could be filled up by anybody if it is signed by the account holder of the cheque. 17. In Opts Marketing Pvt. Ltd. v. State of A.P. MANU/AP/0119/2001 : 2001 CriLJ 1489 (supra), a full bench of this Court while considering the question of quashing the proceedings under Section 482 of Cr.P.C. relating to the offences under Sections 420. IPC and Section 138 of N.I. Act held as follows: Even after introduction of Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, prosecution under Section 420, IPC is maintainable in case of dishonour of cheques or post dated cheques issued towards payment of price of the goods purchased or hand loan taken, or in discharge of an antecedent debt or towards payment of goods supplied earlier, if the charge-sheet contains an allegation that the accused had dishonest intention not to pay even at the time of issuance of the cheque, and the act of issuing the cheque, which was dishonoured, caused damage to his mind,

body or reputation. Private complaint or FIR alleging offence under Section 420, IPC for dishonour of cheques or post-dated cheques cannot be quashed under Section 482 of Cr.P.C. if the averments in the complaint show that the accused had, with a dishonest intention and to cause damage to his mind, body or reputation, issued the cheque which was not honoured. 18. The definition of cheating as defined under Section 415. IPC reads as follows: 415. Cheating : Whoever, by deceiving any person, fraudulently or dishonestly induces the person so deceived to deliver any property to any person or to consent that any person shall retain any property, or intentionally induces the person so deceived, and which act or omission causes or is likely to cause damage or harm to that person in body, mind, reputation or property, is said to "cheat". The ingredients of the above section will be attracted if there was mens rea for the accused to induce the complainant to part with the money making him to believe that it would be adjusted towards the debt. 19. P.W. 1 is the complainant. P.W. 2 is the witness, who claims to be present on 5-4-2003 on which date the petitioner/accused borrowed Rs. 2.50,000/- from the complainant as hand loan and issued Ex. P1 post-dated cheque dated 5-9-2004. The complainant besides examining himself as P.W. 1, examined P.W. 2 to speak of the transaction on 5-4-2003. With the evidence of P.W. 2. the complainant proved basic facts of borrowing and issuing of Ex. P1 cheque by the petitioner-accused. Once the basic facts stand proved by the complainant, he discharges the initial burden. Then, it is for the petitioner/accused to rebut the presumptions that are drawn in favour of the complainant under Sections 118 and 139 of the N.I. Act. The petitioner/accused did not choose to examine himself to rebut the presumptions. Of course, it is well settled that the accused need not enter into the box to rebut the presumptions. He can make out his case from the material brought on record by the complainant. Though P.W. 1 and P.W. 2 were cross-examined by the petitioner/accused, nothing material was elicited to rebut the presumptions under Sections 118 and 139 of the N.I. Act. There is no consistency in the plea advanced by the petitioner/accused. It was suggested to P.W. I that he obtained blank cheques as security for the investment in the films and T.V. Serials produced and directed by him (petitioner/accused). The said suggestion was denied by P.W. 1. It is not even elicited from P.W. 1 as to the quantum of amount proposed to be invested by him in films/T.V. serials produced and directed by the petitioneraccused and what was the reason for not launching the production/direction of the films/T.V. serials. 20. The trial Court and the appellate Court are on appreciation of evidence brought on record reached a concurrent finding that the petitioner/accused failed to produce any material to dispel the presumptions under Sections 118 and 139 of the N.I. Act. When the concurrent finding was given by the trial Court as well as the appellate Court based on strong and reasonable evidence, no interference against the said finding is warranted in revision. 21. Learned senior counsel appearing for the petitioner-accused would contend that there was no proper notice in accordance with the provisions of law embodied in the N.I. Act. According to him, the complainant having known the fact of the petitioner shifting his residence to Chennai sent notice as provided Under Section 138(b) of N.I. Act to Hyderabad address of the petitioner. The same point was urged before the trial Court as well as the lower appellate Court. The trial Court having noticed of non-denial of the petitioner with regard to the address mentioned on Ex. P.4-acknowledgment proceeded to record a finding that the statutory notice has been sent to the correct address of the petitioner. For better appreciation 1 may refer the relevant portion of the order of the trial court on this aspect, which reads as under: Learned Advocate for the accused argued that no notice was served on the accused and that Ex.P.4 acknowledgment does not bear the signature of the accused. It is contended by the complainant that the statutory notice was issued to correct address of the accused and it is deemed to be served on the accused.

Complainant as P.W. 1 during his cross-examination stated that he does not know whether signature on Ex. P.4 acknowledgment is that of the accused. He denied a suggestion that Ex. P.4 postal acknowledgment is not connected with Ex. P.3 notice. The accused did not deny the address that furnished on Ex. P.4 postal acknowledgment. The same address was furnished in the complaint and summons were issued to the accused on the same address. In the circumstances of the case and for the above reasons, I hold that the statutory notice was sent to the correct address of the accused and therefore I hold that the notice is deemed to be served. The contention of the learned Advocate for the accused that no notice was served on the accused, cannot be accepted. Hence, I answered the point against the accused. The appellate Court rejected the contention of the petitioner with regard to nonservice of statutory notice. Para 33 of the judgment of the appellate Court reads as under: 33. As can be seen from Exs. P3 and P4, the statutory notice was addressed to the residence of the accused in Plot No. 9, Road No. 82, Film Nagar, Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad. The selfsame address is furnished on the complaint. The accused is not disputing about the receipt of summons as per the address furnished on the complaint and about his making appearance before the trial Court to face trial. It is pertinent to note that the accused did not dispute about the correctness of his residential address as furnished on the complaint. Ex. P.3 statutory notice and Ex. P4 registered post with acknowledgment. The accused is also not disputing the fact that the complainant sent the original of Ex. P3 by way of registered post. The material brought on record clearly establishes that the complainant sent the notice to the correct address of the petitioner. Thus, notice sent to the petitioner is in accordance with the provisions of Section 138(b) of N.I. Act. 22. The complainant/P.W. 1 is able to establish that the petitioner/accused borrowed Rs. 2,50,000/- on 5-4-2003 and issued Ex. P1 post-dated cheque. On presentation of the cheque, it came to be dishonoured and thereupon the complainant/P.W.1 issued Ex. P3 notice calling upon him to make good the amount covered under the cheque in question. The petitioner/accused received the notice, but failed to give reply. The complainant/P.W. 1 presented the complaint. All the essential ingredients of Section 138 of the N.I. Act have been made out by the complainant. Therefore, there is no flaw in the finding recorded by the trial Court as well as the appellant Court with regard to conviction of the petitioner/accused for the offence under Section 138 of the N.I. Act. 23. Coming to the offence under Section 420, IPC, P.W. 3 is the Manager of the Bank wherein the petitioner/accused maintained the account. He categorically stated that the petitioner/accused closed the account on 24-1-2003 i.e. much prior to the issuance of Ex. P1 cheque. The very fact of the petitioner/accused issuing the cheque after closing the account indicates of his intention to deceive the complainant/P.W. 1 from the inception. Therefore, the trial Court as well as the appellate Court appreciated the evidence brought on record in right perspective and found the petitioner/accused guilty for the offence under Section 420, IPC. 24. The respondent contended that the sentence of imprisonment imposed for the offence under Sections 420. IPC and 138 of N.I. Act cannot be ordered to run concurrently as they are two distinct offences. He placed reliance on the decision of Bombay High Court in Rajendra B. Choudhari v. State of Maharashtra MANU/MH/1094/2006 : 2007 CriLJ 844. The cited decision refers to the powers of the Court Under Section 482 of Cr.P.C. with regard to direction to run subsequent sentence concurrently with previous sentence. It has been held in the cited decision that Section 482 of Cr.P.C. cannot be invoked in view of the specific provision under Section 427 of Cr. PC. para 5 of the judgment needs to be noted and it is thus: (5) Lastly, it is contended that the Magistrate ought to have directed that the sentences imposed in these trials should run concurrently with the previous sentence, in view of Section 427 of the Code. According to learned Counsel, it is permissible for this Court to give such a direction to meet the ends of justice.