Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Disfimisi Stis Polities USA

Uploaded by

thanasis alampasisOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Disfimisi Stis Polities USA

Uploaded by

thanasis alampasisCopyright:

Available Formats

http://www.dancingwithlawyers.com/freeinfo/libel-slander-per-se.

shtml

May 19, 2005

This is a list of states which recognize "defamation per se", or if you want to stretch

legalese a bit, are "defamation per se states." (It's not correct to say that a state which

doesn't "is a defamation per quod state.") There are states which recognize defamation

per se, and six which do not make a distinction.

There is a deeper description below the list of states, which explains the historic

distinction between defamation per se and per quod, and why it matters (or used to

matter). It also provides the common law categories that current slander law is based

on.

Alabama (AL) – Yes

Alaska (AK) – Yes

Arizona (AR) – No

Arkansas (AR) – No

California (CA) – Yes

Colorado (CO) – Yes

Connecticut (CT) – Yes

Delaware (DE) – Yes

Florida (FL) – Yes

Georgia (GA) – Yes

Hawaii (HI) – Yes

Idaho (ID) – Yes

Illinois (IL) – Yes

Indiana (IN) – Yes

Iowa (IA) – Yes

Kansas (KS) – Yes

Kentucky (KY) – Yes

Louisiana (LA) – Yes

Maine (ME) – Yes

Maryland (MD) – Yes

Massachusetts (MA) Yes

Michigan (MI) – Yes

Minnesota (MN) – Yes

Mississippi (MS) – No

Missouri (MO) – No

Montana (MT) – Yes

Nebraska (NB) – Yes

Nevada (NV) – Yes

New Hampshire (NH) – Yes

New Jersey (NJ) – Yes

New Mexico (NM) – Yes

New York (NY) – Yes

North Carolina (NC) – Yes

North Dakota (ND) – Yes

Ohio (OH) – Yes

Oklahoma (OK) – Yes

Oregon (OR) – No

Pennsylvania (PA) – Yes

Rhode Island (RI) – Yes

South Carolina (SC) – Yes

South Dakota (SD) – Yes

Tennessee (TN) – No

Texas (TX) – Yes

Utah (UT) – Yes

Vermont (VT) – Yes

Virginia (VA) – Yes

Washington (WA) – Yes

Washington, D.C. (DC) – Yes

Wisconsin (WI) – Yes

Wyoming (WY) – Yes

Generally, per se indicates that a statement is defamatory on its face (from Latin, "for

itself" or "of itself"). For example, a former employer wrongly tells someone that you

extorted money from the company.

Defamation per quod depends on context and the interpretation of the listener. It

means that a person would have to have what's called extrinsic knowledge to

understand the statement as defamatory. For example, a former employer wrongly

says he saw you drinking whiskey in a bar, a statement that could be problematic if

the person the employer is talking to knows you were court-ordered last year to stay

sober.

Under common law, slander traditionally was actionable per se if it fell into one of

four categories:

• imputations of criminal conduct

• allegations injurious to another in their trade, business, or profession

• imputations of loathsome disease

• imputations of unchastity in a woman

The wording may have changed as society has changed, but the four basic common-

law categories still underpin the law. (Some lawyers feel that "unfit for work" is now

a fifth category, but that's still hazy.) "Unchastity" is essentially meaningless as an

accusation against an adult woman, but probably still grounds for legal action when

made against a teenage girl. (The "growth industry" we see from readers' emails is

accusations of child molesting, almost always made against men. "Predatory"

behavior claims are growing, and we have started to see "inappropriate touching.")

The distinction between defamation per se and per quod used to be relevant mainly

when it came to pleading for damages. Historically, someone who was judged the

victim of slander per se would not have to prove that it had resulted in "special harm"

– that is, the loss of something with an economic value – while someone who was the

object of slander per quod would have to prove specific harm. But times were simpler.

Claim that a 1870's cattle rancher had not paid you, and you could destroy his credit

rating forever – in such a situation it wouldn't matter much whether it had been

slander per se or slander per quod.

Courts in most states still technically distinguish between defamation per se and

defamation per quod. However, the effect of the distinction has been hugely diluted

by federal rulings (such as the landmark libel case Gertz v. Robert Welch Inc.) that

have declared that damages "may not be presumed" – a way of saying, "mebbe yes,

mebbe no."

Even in the states where the per se distinction continues to be a factor, it isn't a

guarantee of big awards. If you can't show you were damaged by a statement that was

defamatory per se, it's possible a trial could result in a finding for you – but only $1 or

some other token amount in damages.

It's important to understand that lawyers and judges can't always make a clear

distinction either. "This ostensibly simple classification system," writes Rodney

Smolla, dean of the University of Richmond School of Law, "has gone through so

many bizarre twists and turns over the last two centuries that the entire area is now a

baffling maze of terms with double meanings, variations upon variations, and multiple

lines of precedent."

In short, defamation of character law is a mess. The difference between defamation of

character per se and per quod is also a mess – a mess that doesn't make much

difference to your plans, unless you're just trying to win a moral victory in court.

###

For a more complete description of lawsuits that do win monetary damages – such as

"financial harms" or "emotional distress" – please see our report Fighting Slander,

sold with a full money-back guarantee.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Kane's Home Arrest ThoughtsDocument7 pagesKane's Home Arrest ThoughtsDave BiscobingNo ratings yet

- Industrial Development and Regulation ActDocument20 pagesIndustrial Development and Regulation ActRajesh Dey100% (1)

- Brief: Joachim Behnke and Friedrich Pukelsheim (August 31)Document9 pagesBrief: Joachim Behnke and Friedrich Pukelsheim (August 31)CPAC TVNo ratings yet

- Stages of Dev't Erik EriksonDocument25 pagesStages of Dev't Erik EriksonRabhak Khal-HadjjNo ratings yet

- Teresa Electric Power Co. Inc v. PSCDocument2 pagesTeresa Electric Power Co. Inc v. PSCJustin MoretoNo ratings yet

- Pacific Farms, Inc. vs. EsguerraDocument2 pagesPacific Farms, Inc. vs. EsguerraInghridBusaNo ratings yet

- West Philippine Sea RulingDocument2 pagesWest Philippine Sea RulingNoreenNo ratings yet

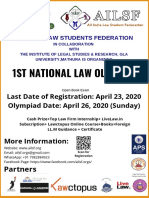

- 1st National Law Olympiad-05 PDFDocument7 pages1st National Law Olympiad-05 PDFKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- BlackBerry 10 OS 10.3.2.2474-10.3.2.2836-Release Notes-EnDocument7 pagesBlackBerry 10 OS 10.3.2.2474-10.3.2.2836-Release Notes-EnAtish Kumar ChouhanNo ratings yet

- EFS MARKETING, INC., Plaintiff-Appellee-Cross-Appellant, v. RUSS BERRIE & COMPANY, INC., and Russell Berrie, Defendants-Appellants-Cross-AppelleesDocument10 pagesEFS MARKETING, INC., Plaintiff-Appellee-Cross-Appellant, v. RUSS BERRIE & COMPANY, INC., and Russell Berrie, Defendants-Appellants-Cross-AppelleesScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Damian Grace, Stephen Cohen-Business Ethics-Oxford University Press (2010) PDFDocument410 pagesDamian Grace, Stephen Cohen-Business Ethics-Oxford University Press (2010) PDFeva budianaNo ratings yet

- Business Law and Regulations (BLR)Document6 pagesBusiness Law and Regulations (BLR)Esmeralda ChouNo ratings yet

- The Material Sources of International LawDocument13 pagesThe Material Sources of International Lawmubzz_No ratings yet

- AC No. 2984Document4 pagesAC No. 2984Patrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Carino V CHRDocument3 pagesCarino V CHRJason CalderonNo ratings yet

- Tewelde v. Ashcroft, 4th Cir. (2004)Document8 pagesTewelde v. Ashcroft, 4th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 1 - Name Declaration Correction and PublicationDocument1 page1 - Name Declaration Correction and PublicationJahi100% (1)

- CASE NO: A-20-818973-C Department 24: Attorneys For Plaintiff Alfonso NoyolaDocument19 pagesCASE NO: A-20-818973-C Department 24: Attorneys For Plaintiff Alfonso NoyolaBoulder City ReviewNo ratings yet

- De Liano vs. Court of AppealsDocument18 pagesDe Liano vs. Court of AppealsVincent Ong100% (1)

- Arredondo - OXIO - E340 - Americas Summit - VenezuelaDocument12 pagesArredondo - OXIO - E340 - Americas Summit - VenezuelaricardoNo ratings yet

- Josephine Wee vs. Felicidad MardoDocument5 pagesJosephine Wee vs. Felicidad MardoGarri AtaydeNo ratings yet

- Medicolegal Aspect of Medical RecordsDocument34 pagesMedicolegal Aspect of Medical RecordsWidya Dwi Agustin0% (1)

- Acquiescence and JurisdictionDocument21 pagesAcquiescence and Jurisdictionmao999967% (3)

- Right To Just and Humane Conditions of Work: International Labour Organization Convention NUMBER-187Document17 pagesRight To Just and Humane Conditions of Work: International Labour Organization Convention NUMBER-187Uday singh cheemaNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Seminar Brochure ICMDocument11 pagesCivil Procedure Seminar Brochure ICMBrandon ChanNo ratings yet

- Samsung V AppleDocument32 pagesSamsung V AppleIlyaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Adopt Markings in Pre-Trial OrderDocument3 pagesMotion To Adopt Markings in Pre-Trial OrderNicole SantosNo ratings yet

- Call For PapersDocument2 pagesCall For PapersBar & BenchNo ratings yet

- 54 - PNB vs. CedoDocument2 pages54 - PNB vs. CedoDanilo Jr. ForroNo ratings yet

- 6NCCA-AGPU-CSO 03A-Omnibus Sworn StatementDocument1 page6NCCA-AGPU-CSO 03A-Omnibus Sworn StatementClement AcevedoNo ratings yet