Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coca Cola in India

Uploaded by

Patrick AdamsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Coca Cola in India

Uploaded by

Patrick AdamsCopyright:

Available Formats

CASE STUDY

Coca-Cola in India

Earlier, Cokes mentality here was that well only sell carbonated soft drinks (CSD). Alex Von Behr, CEO, Coca-Cola India1 An aggressive expansion of the affordable 200ml single-serve pack has reignited the Indian market, particularly in rural areas that are home to 70% of the population. Our overall business in India produced high double-digit growth in 2002- a significant result for this important market. The Coca-Cola Company, Annual Report 2002.

n 2003, Coke India, the Indian arm of the Coca-Cola Company (Coke) was awarded the Robert W. Woodruff Award2 for outstanding business performance. This culminated a major turnaround for a company that had struggled right from the time it had entered India in 1993. Under CEO, Alex Von Behr, CCI posted its first ever profits in 2001. After a successful stint as Von Behr prepared to move to another part of Cokes global system in July 2003, his successor Sanjiv Gupta seemed to be taking charge of a much healthier company. Coke (founded in 1886) was the worlds leading manufacturer, marketer, and distributor of non-alcoholic beverage concentrates and syrups, used to produce more than 300 beverage brands. Headquartered at Atlanta, US, it has local operations in over 200 countries. It generated net income of $3 bn over sales of $19.5 bn. Coke had 56,000 employees worldwide. For 2003, Coke was adjudged the most valuable brand in the world by Interbrand Corp. It was valued at $70.45 bn. Cokes turnaround in India had come after a period of heavy investments. During the period 19932002, Coke had invested $1 bn in India, of which $805 mn was invested in its bottling subsidiary, Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Pvt., Ltd., (HCCB). In 2003, it had 17 manufacturing units (company and franchisee owned bottling operations), 60 distribution centers catering to 5,000 distributors and one mn retail outlets, serviced via trucks and three-wheelers. Coke India directly employed 10,000 employees. It was the biggest procurer of chilling equipment, glass, sugar and mango pulp in India.

Background note

Coke had been the market leader in the Indian Carbonated Soft Drinks (CSD) market till 1977. But it decided to opt out of the Indian market in 1977 when the Socialist Janata Party government asked

1 2

Shailesh Dobhal, Coke s Second Wind, Business Today, February 3, 2002. Robert W Woodruff served as head of Coke for 50 years (1923-1985). The Robert W. Woodruff award is given to the Coke operation that exhibits outstanding business performance in terms of volume, profitability and quality. 75

Global CEO September 2003 ICFAI Press. All Rights Reserved.

Coca-Cola in India

Figure 1 Soft drink market: Per capita consumption, 2002

1600 1400 8-ounce servings 1200 1404 1484

Servings

1000 800 600 471 400 200 7 0

ia Ind n ista Pak na Chi sia Rus

984

565

278 14 89 124

a fric zil th A Bra Sou

an Jap

ny ma Ger

US

xico Me

Source: Deutsche Bank

the company to cut its equity to 40% and to reveal its secret formula. In the late 1980s, Roberto C. Goizueta, CEO of the parent company, began to give a new thrust to the emerging markets. After moving into Latin America and Eastern Europe, Coke entered China in 1988. These events set the stage for Cokes re-entry into India in 1993. The entry into India also made sense in view of the opening up of the countrys economy in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, Cokes archrival, Pepsi had already entered India in 1990. It launched its first product Lehar Pepsi in June 1990. Pepsi concentrated on building a very strong retailer network. It also struck the right chord with its advertisements focussed on the youth. By the time Coke entered India, Pepsi seemed to have got over teething problems. The company had overcome resistance from Indias government bureaucrats. Pepsi had also dealt with competition from local businessman Ramesh Chauhan (Chauhan) of the Parle Group in an aggressive manner. Parle group gave a tough competition to Coke in the 1970s. After the departure of Coke in 1977, Chauhans Parle Exports formulated an alternate cola drink Thums Up, a lime-and-lemon drink Limca and other soft drinks. By 1993, Chauhan built these products into national brands commanding a marketshare of 60% in the Indian soft drinks market while Pepsi was trailing with 25% marketshare. The bottling operations were majority franchisee owned. Like in other emerging markets, the main challenge for CSD companies was to increase consumption. In 1993, the per capita consumption in India was three bottles per year compared to 700 bottles for US. So, both Cone Cola India(CCI) and Pepsi focussed on market growth. Through aggressive marketing and different pricing and packaging initiatives, the two companies lifted the growth rates from 2.5 to 6% in the early 1990s. The share of cola drinks in the CSD market increased from 30% in 1994 to 50% in 1998.3 (Figure 1)

CCI Under Jayadev Raja

Finding Pepsi already well entrenched in the market, CCIs founding CEO, Jayadev Raja acquired the four popular brands ThumsUp, Gold Spot, Limca and Citra from Parle group. In 1993, these brands

3

www.indiainfoline.com 76 Global CEO September 2003

CASE STUDY

Exhibit: I CCI: Brand portfolio

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Coca-Cola Diet Coke Sprite Fanta Schweppes Thums Up Limca Maaza Citra Gold Spot Kinley water Sunfill concentrate Shock Rimzim

Exhibit: II Soft drink market: Production in India

Year 1990-91 1991-92 1992-93 1993-94 1994-95 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 Production (million bottles) 2195 2490 2800 3000 3240 4000 4450 4920 5670 6480 7000

Source: The Coca-Cola Company, 2003

Source: www.indiainfoline.com

accounted for 60% of the Indian CSD market. Coke also got access to Parles bottling and distribution network. 56 bottling plants and 6,000 workers came to the CCI fold. The acquisition expanded CCIs portfolio of brands to ten, including two orange drinks (Fanta and Gold Spot) and two clear lime drinks (Sprite and Citra). Implementation of the agreement with Parle was not smooth. The agreement included clauses, which resulted in much acrimony between Parle and Coke. Ramesh Chauhan was retained as a consultant to CCI and had the first right of refusal for a big bottling plant for the Pune-Bangalore corridor. Ramesh Chauhan also remained as a bottler for the biggest markets of Delhi and Mumbai along with his brother Prakash Chauhan. But as time passed by, it appeared as though Ramesh Chauhan was unhappy at being ignored. Coke on its part also became suspicious of Chauhan. There were speculations that Ramesh Chauhan was trying to control many bottlers through his informal network. So CCI was looking for an opportunity to buy out Chauhans bottling operations as well. This later would have major implications for CCI. In the initial years, CCI focused on establishing the Coca-Cola brand quickly. The marketing campaign positioned Coca-Cola as an international brand and did not emphasize local association. Coke, as a deliberate strategy, decided not to spend heavily on promoting Thums Up. Indeed the marketing spend on Thums Up between 1993 and 1996 was almost negligible. The overall marketing effort was also not focused as CCI changed the head of marketing three times during the period. Thums Up remained neglected. Inadequate marketing support for other Parle brands also led to their declining market shares. Coke also faced major challenges on the bottling front. CCI chose to enter the market with a franchise-bottling model and to establish its own bottling network later as the volumes grew. It had started operations with all 56 franchisee bottlers acquired from Parle. The operations of these small bottlers with sub optimal capacities were highly inefficient. The efficiency of an average bottler in India was 200 bottles per minute (bpm) while Cokes global standard was 1200-1600 bpm. As CCI wanted to penetrate the market fast through aggressive marketing, leaving the bottling to franchisees, it had to depend on these inefficient bottlers.

Global CEO September 2003 77

Coca-Cola in India

Figure 2 Indian soft drink market: Composition of Cola & Non-Cola drinks

Other Pepsi 1% Thums Up 22%

Figure 3 Indian soft drink market: Consumption pattern

Home 20%

Other Cola brands 5% Limca 10% Mirinda 8% Fanta 9% Gold Spot 2%

Coca-Cola 13%

On Premises 80% Pepsi 30%

Source: Center for Industrial & Economic Research Industrial Techno-economic Services Pvt. Ltd, 2002.

Source: Forbes, December 20, 2002.

The bottlers taken over by Coke also had problems adjusting to a new work culture. Working with professional managers was quite different from dealing with Ramesh Chauhan. CCI wanted bottlers to strengthen their operations and distribution network by introducing more personnel and trucks. The bottlers on their part felt that till volumes went up, upgrading the facilities did not make sense. Instead they wanted CCI to spend more on marketing and advertising to build volumes first. They sought the help of Ramesh Chauhan, who was Cokes biggest bottler, to convey their grievances. Chauhan argued that CCIs lack of interest in promoting Thums Up was resulting in falling sales and asked CCI to take corrective action. He also complained that CCI was not interested in giving him the right to set up the bottling plant for the Pune-Bangalore corridor as promised.

CCI under Richard Nicholas

In June 1995, Richard Nicholas III (Nicholas) replaced Jayadev Raja. Nicholass brief was to make major inroads into the institutional accounts. As he concentrated on bulk deals, Coke seemed to ignore the consumer market. It also found itself handicapped by lack of operational autonomy. It did not have the freedom in pricing and product introduction and received guidance from the head quarters at Atlanta for most decisions. Meanwhile, the problems with bottlers continued to grow. The head quarters sent joint venture agreements to the bottlers asking them to raise their efficiencies to its world standards or sell out. Bottlers spent crores of rupees in upgrading capacity from 200 to 400 bpm, when the margin on a bottle of Coke, for the bottler, was no more than 5%. The bottlers started feeling that CCI wanted to grow at their expense. Some bottlers like Pinakin Shah, Cokes Ahmedabad based bottler started switching their loyalty to Pepsi. The restrictive arrangements and inadequate marketing support also angered the bottlers. Meanwhile, Cokes promotion efforts did not seem to be effective. They were focused on mega events like the 1996 Cricket World Cup held in India. CCIs World Cup Cricket campaign was overshadowed by Pepsis Nothing official about it campaign. Major analysts were surprised that Thums Up was totally out of the picture during such a mega event.

78 Global CEO September 2003

CASE STUDY

Figure 4 Soft drinks market: Industry structure

Non-Alcoholic soft drinks

Fruit drinks Tropicana real

Soft drinks

Carbonated drinks

Non-carbonated drinks

Cola products

Non-Cola products

Pepsi Coca-Cola Thums UP Diet Coke Diet Pepsi

Fanta & Mirinda - Orange based drinks Limca and Mirinda Lemon - Cloudy LIme based drinks 7Up, Sprite, Canada Dry and Mountain Dew Clear Lime drinks Frooti and Maaza - Mango based drinks Source: www.indiainfoline.com

CCI Under Donald Short

CCI recognized that bottler integration and increased efficiency in bottling operations held the key to its success in India. In April 1997, Donald Short was brought-in from Coca-Cola Japan to replace Richard Nicholas. Shorts brief was to streamline the inefficient bottling operations and the supply chain. Short began efforts to turn CCI from a franchisee-bottling model into a majority company owned bottling operation. Towards the end of 1997, bottling agreements between Coke and many of its bottlers were expiring. The bottlers were given an offer to sell out. Short appointed Ernst and Young as independent evaluators and integrated 40 out of the 54 bottlers through joint ventures or buy-outs. He acquired Ramesh Chauhans bottling operations in Delhi and Mumbai in late 1998. CCI spent nearly Rs. 1500 cr acquiring the bottlers. The prices paid for the plants included goodwill for market development for the years 1993 to 1997, and compensation for loss of earnings for a few years. Children of former owners were also given jobs. But as the restructuring exercise proceeded, lawsuits were filed by bottlers who charged CCI with using unethical methods while making the acquisitions. Pepsi took advantage of the situation to wean away some bottlers like Goa Bottling. In an effort to increase their reach, both the companies were also involved in poaching of retailers and employees. Short hiked salaries offering marketing personnel 300-400% more pay than Pepsi. Around 20 Pepsi employees moved to CCI. This prompted Pepsi to file a case against CCI. There were also rumors that the distributors of the two companies had also hoarded glass bottles to disturb each others operations in the region.

Global CEO September 2003 79

Coca-Cola in India

Exhibit III - CCI: Controversial clauses

Under clause 1(1) of the agreement of Coca-Cola with its bottlers, the company authorizes the bottler and the bottler undertakes to prepare and package the beverages in authorized containers and to distribute and sell the same under the trademarks, but only in and throughout the territory, which is defined and described to it. That is, the bottler can sell and distribute the beverages only in the territory, which has been defined and described by the company. Clause 6 of the agreement restricts the bottler to sell and distribute the beverages only to retail outlets or final consumers in the territory. The intention of this clause was to eliminate the possibility of other companies buying Cokes beverages and selling it under different trademarks. Clause 17(a) forbids the bottler from taking up business activity in any manner in any other beverage products except those prepared under the authority of Coca-Cola. Clause 17(e) prevents the bottler from engaging in the manufacture of any kind of Cola beverages for a period of two years in the event of termination of agreement.

Short initiated the localization of marketing efforts. He signed up celebrities like Aamir Khan, Aishwarya Rai, and Sunil Gavaskar to promote Coke (See figure 6). He also began efforts to rejuvenate the Parle brands, Limca and Thums Up. In 1998, India was declared the fastest growing market within the Coca-Cola system. But things were far from normal. Attempts at building growth through discounts and PET4 take home segment were not very successful because of lack of coordination between the launches and marketing back-up. The bulging employee strength continued to bleed CCI. Employee rationalization became an important aspect needing urgent attention. In early 1999, the parent company acquired Cadbury Schweppes. As a result, 12 more bottlers were brought into CCIs fold. This acquisition added Crush, Canada Dry and Sport Cola to CCIs product line. This meant CCI had three orange, clear lime and Cola drinks each in its portfolio. In November 1999, Douglas Jackson took charge of Cokes Indian operation from Donald Short. He held the position for only three months before Alex Von Behr took charge in January 2000.

CCI under Alex Von Behr

Before taking up the assignment in India, Von Behr had been senior Vice-President of F&N5 CocaCola Singapore, reporting to Douglas Daft who headed the Japan and the Asia Pacific region. When Daft became the CEO of the parent company, he deputed Von Behr to head the operations in India. Von Behr came to India at a time when Coke seemed to have hit the trough. Huge sums had been spent on buying out and restructuring local drinks manufacturers and bottlers. Lavish spending on advertising and marketing had failed to produce enough extra sales. To maintain good relationships with bottlers and avoid defections to the other camp, dealers had been pampered by offering expensive overseas trips. In 2000, Coke wrote off investments in India, amounting to $400 mn. The revised value of CCIs assets after the charge was $300 mn. Meanwhile, the push for increase in volume had taken its toll on the internal systems of the company. In March 2000, CCI received reports of gross violation of discounting terms, credit policies and dubious cash management by its North Indian operations. The company initiated an enquiry into the matter with the help of accounting consultants Arthur Anderson. The team inspected regional offices, distribution centers and bottling plants in the Northern region to verify the accounts and other

4 5

Polyethylene Terephthalate plastic bottles Fraser and Neave (F&N), an aerated drinks company held the franchise of Coca-Cola for Singapore and Malaysia since 1936. 80 Global CEO September 2003

CASE STUDY

Exhibit IV - Indian CSD market: Market share of Coke & Pepsi

Pepsi (%) 1996 1997 1998 33.3 34.5 35.3 Coca-Cola (%) 59.9 58.9 60.4 Others (%) 7 6.6 4.3

transactions. The findings revealed gross violation of discounting norms. Discounts were as high as five times as those offered in other regions. There had also been arbitrary appointments and cancellations of dealerships.

The findings were followed by a detailed performance appraisal, which led to the 1999 36 61.4 2.5 resignation of 70 managers in July-November 2000. The employees alleged that the top Source: ORG management had approved the discounts and the whole appraisal exercise was a veiled effort to cut down the managerial strength. As the managers left and doubts about whole episode remained, an atmosphere of distrust was created between the lower and middle management and the top management. Von Behr along with Sanjiv Gupta, the Vice-President, Operations and Navin Miglani, the head of human resources realized the need for a complete overhaul. Gupta had worked with Hindustan Lever, Unilevers Indian subsidiary and knew the Indian markets well. The top management team decided to reposition CCI as a beverage company rather than a CSD company. They convinced Cokes Atlanta Headquarters to introduce new affordable package sizes to increase beverage consumption and revamp Thums Up and other Parle brands. They also identified a few key focus areas: Regionalization of business through better understanding of the customer Decentralization of operations and empowerment at local area levels Integration of bottlers for greater efficiency and cost cutting Establishing systems and values to support the new structure.

In 1997, CCI had signed an agreement with Government of India to disinvest 49% in favor of the Indian public to bring in $700 mn into India. But, in 2000, CCIs return on investment was only Rs. 3 per share for a face value of Rs. 10 per share. So it was reluctant to go ahead with the divestment. This led to friction between the Government of India and CCI. So in August 2002, Coke divested 49% stake in its bottling subsidiary HCCB through private placement (33%), to employees and stock option trusts (10%) and bottlers (6%) raising $41.6 mn in the process. This move was part of the parent companys efforts to improve relations with Figure 5 governments across the world. Non-cola products: Segmentation on the basis of flavors Reorienting marketing The new marketing initiatives launched by Coke in India were influenced by the direction Coke was taking globally under Douglas Daft (See Exhibit: V for restructuring under Douglas Daft). The parent company had introduced several drinks in Asia as part of its regionalization drive and expanded its portfolio to 300 brands. In emerging and developing markets, the parent companys focus was on availability of affordable products for consumers. Von Behr realized that regional brands not only required minimum advertising support but

Global CEO September 2003

Soda 21% Lemon Cloudy 18%

Lemon Clear 8% Mango 8%

Orange 45%

Source: Center for Industrial & Economic Research Industrial Techno-economic Services Pvt. Ltd, 2002

81

Coca-Cola in India

Exhibit V The Coca-Cola company: Restructuring under Douglas Daft

Douglas Daft became the 11th CEO of the Coca-Cola Company in February 2000. He inherited a company that faced a range of problems- falling profits, internal discord from racial discrimination law suits, strained relations with bottlers and European regulators, a bruised corporate image resulting from the June 1999 Belgian contamination scare and widespread accusations of anti-competitive business practices. During the 1980s, Coke had enjoyed explosive growth. It had expanded its bottling network around the world, and pushed its four core brandsCoke, Diet Coke, Sprite, and Fantathrough this network. But when the global downturn came in the late 1990s, sales slumped. Coke realized that there was a limit to the consumption levels for carbonated sodas, particularly in mature markets like US and Western Europe. Daft looked for new ways of boosting growth. He embarked upon a restructuring program with the motto Expanding from global to local, which would ensure that Coke continues to be welcome around the world, and that we apply community and neighbor equally to those who live next door, or on the next continent.6 Coke scientists and marketers developed an array of new products from calcium-fortified waters and vitamin-enriched drinks bearing the names of Disney characters to a purified water filtration system for home use. While Coke sold over 300 beverages worldwide, Daft looked forward to the day when Coke would offer more than 2,000 beverages including new juices, teas, and hybrid products like carbonated tea. He explained: We want to ensure that we always have a tailored non-alcoholic beverage portfolio in every community that touches consumers in locally relevant ways.7 Coke also built joint ventures to enter non-carbonated drinks segment. It joined hands with two major players, Procter & Gamble (P&G) and Nestl, who had a significant presence in non-carbonated drinks. P&Gs nascent Elations, cranberry juice, which relieved pain caused by arthritis was pushed through Cokes worldclass distribution system and marketing prowess. Coke in turn banked on P&Gs product innovation and technological capabilities to develop new snack and beverages. With Nestl, Coke marketed coffee and tea globally. Daft pushed managerial responsibilities down to local operating units. All of Cokes Asian and European regional heads were transferred from Atlanta and placed in their local markets. Earlier Coke believed in national marketing for its brands. Under the new set up, it gave its bottlers free rein to tailor promotions to local events. Daft also announced an incubator project providing office space and seed money to start-ups with innovative ideas that could benefit Coke. In 2000, Cokes global workforce of 29,000 was pruned by 20% (mainly from marketing, sales and customer support). Coke eased out or reassigned 30 of its top 32 managers.8 The moves were intended to smash what Daft viewed as a stifling bureaucracy and push down decision-making to the field managers. Improving relations with bottlers and European regulators was also high on Dafts agenda. Daft traveled extensively in Europe meeting bottlers, legislators, regulators and community leaders to communicate the vision of the new Coca-Cola Company, which he emphasized, was built on humility and dedicated to local tastes. Source: Coca-Cola Annual Report, 2002

they also increased the viability of bottling operations. CCI spent $3.5 mn to beef up advertising and distribution for Thums Up. By 2002, it had become Indias No.2 cola drink after Pepsi. Maaza, the mango drink, was repositioned as a juice brand and saw a growth of almost 30% in 2001. Since India was a large country of different tastes and cultures, CCI customized its marketing strategy for different regions. It promoted the Coke brand in Delhi, Thums Up in Mumbai and Andhra Pradesh, and Fanta in Tamil Nadu. Coke had plans to launch Rimzim, a spicy soda drink in North Maharashtra. Different

6 7

Betsy McKay, Coca-Cola Names Carl Ware Head of Global Public Affairs, Dow Jones News Service, 4th January 2000. The Coca-Cola Company updates on business strategies and confirms long-term volume and EPS growth objectives, Coca-Cola Press release, 11th April, 2000. Repairing the Coke Machine, Business Week, March 19, 2001. 82 Global CEO September 2003

CASE STUDY

Figure 6 CCI: TV Commercials in the late 1990s and early 2000s campaign: Life ho toh aisi

Indian Cricket stars Sunil Gavaskar and Virendra Sehwag promoting Coca-Cola. After a swig Gavaskar swings the bottle to Sehwag and asks teasingly, Square cut mein toh koi...problem nahin hain na? (Hope you dont have a problem with your squarecut shot) Breaking into fits of laughter they walk arm and shoulder. Jingle: Life ho toh aisi.

Campaign: Jo Chaho ho jaaye

Indian film star Hrithik Roshan and Aditi promoted Coca Cola during Diwali (Indian festival) with Jo Chaho ho Jayee (Whatever you wish- will happen) Campaign. Aditi said to Hrithik, Happy Diwali, the fireworks form the Coke baseline in the sky: Jo chaho ho jaye Coca-Cola enjoy.

Campaign: Life ho toh aisi

Campaign: Thanda Matlab Coca-Cola

Indian film actress Aishwarya Rai saying: Super: Life ho toh aisi! (This is Life) Coca-Cola.

Indian film star Amir Khan in ...Thanda matlab? Coca-Cola, (Cool means?.. Coca-Cola) Ad campaign.

Source: www.agencyfaqs.com

Global CEO September 2003 83

Coca-Cola in India

Figure 7 CCI: Award winning Ad in the early 2003

Coca-Colas aggressive ad campaign starring Aamir Khan creating consciousness of Indians that the chota Coke was for just Rs.5. The national ad campaign was a huge success and won the AAAI and Abby advertising awards. Source: www.agencyfaqs.com

pack sizes were promoted in different parts of the country. The one-liter pack was promoted in Delhi and 1.5-liter pack in Mumbai. Restaurants in Delhi and Mumbai and Paan-bidi and grocery outlets in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu were targeted as the preferred channel. In 2000, CCI introduced Sunfill, a ready to drink (RTD) concentrate. Regional marketers were used to increase its reach (in Tamil Nadu Sunfill was distributed by Medimix). An estimated 200 mn Indians who did not drink CSDs were added to Cokes target market. CCI decided to give its marketing efforts a local flavor by leveraging festivals like Durga Puja in Calcutta, and Dandiya in Gujarat. CCI also started focusing on the youth market. Cokes positioning was similar to that of Pepsi but it outspent Pepsi by three times on media campaigns. It slowly started talking about youth passions like cricket, films, festivals and food. It signed on cricketers and popular film stars for its advertisements. It also modified film hits to frame catchlines that appealed to the youth. At times the advertising got personal also. One TV commercial, starring popular Indian actor Aamir Khan projected the Indian image and the affordability of the 200ml bottle. The campaign was a huge success. CCI decided to promote all the 10 brands to crowd out Pepsi. While Thums Up was associated with adventure sports, Sprite was used Figure 8 to take potshots at Pepsi. Coke: Ad, Piyo thanda, jiyo thanda (Have cool, live cool) Coke learnt with experience that price was a strategic weapon in an emerging market like India. An increase in value added tax in 1996 had taken the price of the 300ml bottle beyond the reach of many Indian consumers. In 2000, CCI conducted a year-long experiment in coastal Andhra Pradesh by introducing a 200ml bottle at Rs.7. The volumes went up by 30% demonstrating the importance of consumer affordability. So the 200ml pack priced at Rs. 5 was rolled out countrywide in January 2003. The advertising campaign highlighted the affordability and Indian image. Bottled water was another area where Coke identified major opportunities. In 2002, Packaged

Global CEO September 2003

Film star, Vivek Oberoi, at the launch of a new ad campaign in 2003. Source: Business Line, April 2, 2003.

84

CASE STUDY

Drinking Water (PDW) in India was a Rs.1, 000 cr industry and growing by 40% every year. PDW was a low margin- high volume business, but it was an attractive proposition for bottlers Others Kinley as it increased plant utilization rates. In this 19% 18% market, Cokes Kinley was pitched against Ramesh Chauhans Bisleri and Pepsis Aquafina Aquafina. The product not only faced intense 12% competition but also was difficult to differentiate. Coke positioned Kinley as natural water with the tag line boond boond Bisleri 34% mein vishwas (Trust in each drop of water). To make it affordable, Coke introduced Source: ORG-Marg/AC Nielsen Kinley in 200 ml pouches for Re.1 in selected places in Ahmedabad and 200 ml water cups in Maharashtra, priced at Rs. 3 per cup in test marketing exercise conducted in mid-2002. In 2002, Kinley with 35% market share had become the leader in the retail PDW segment and was contributing 20% of CCIs revenues. Figure 9 Packaged drinking water: Market shares in July 2002

Streamlining operations

Von Behr revamped the organizational structure to support the regionalization drive. He pushed down responsibilities from corporate headquarters to the local business units. The aim was to effectively align CCIs corporate resources, support systems and culture to leverage the local capabilities. Under Short, CCIs operations had been divided into North, Central and Southern regions. Each region had a president at the top, with divisions comprising marketing, finance, human resources and bottling operations. The heads of the divisions reported to the CEO. Bottling operations were divided into four companies directed by the bottling head from headquarters. Under the new plan, CCI shifted to a six region profit center set up where product customization and packaging, marketing and brand building were taken up locally. A Regional General Manager (RGM) headed each region with the regional functional heads reporting to him. All the RGMs reported to VP (Operations), Sanjiv Gupta, who in turn reported to Von Behr. The four bottling operations, with 37 bottling plants, were merged into Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages (HCCB). Each of the six regions had on an average six bottling plants. Each plant was headed by an Area General Figure 10 Manager (AGM) and held profit center Aerated soft drinks: Market shares responsibility for a business territory. He reported in October 2002 to the RGM as well as the head of bottling at the Others head quarters. 3% Restructuring of bottling activities through joint ventures and acquisitions gathered momentum under Von Behr. Only the 17 most efficient bottling facilities were retained from the 26 company owned and 16 franchisee bottling facilities. Eight unviable bottling plants were shut down. CCI also invested heavily in technology upgradation. The average efficiency of bottling operations increased by 40%. 25 new production

Global CEO September 2003

Pepsi 36%

CCI 61%

Source: AC Nielsen

85

Coca-Cola in India

lines were added while glass and PET capacity was doubled. 5,000 new trucks and autorickshaws were introduced to strengthen the logistics operation. The number of refrigerators in the market was doubled to 500,000 units. The merger of CCIs four bottling operations9 in 1999 had added more than 10,000 employees to CCIs payrolls. So, CCI offered a Voluntary Retirement Scheme to the bottling plant employees. About 1,500 workers accepted the scheme. This decreased the employee costs from 7% of total cost in 2002 to 4.5% in 2003. CCI also started benchmarking its cost structure with its rival in India. The company centralized procurement to generate economies of scale and used local raw materials to substitute imports, saving 57% on import tariffs in the process. Coke also streamlined its distribution. In urban areas, 8 to 10% of CCIs sales were through area market contractors (AMCs) who were equivalent to big retailers. They supplied the soft drinks to smaller retailers and other outlets. In the village areas, Coke used distributors for the sales. AMCs supplied material directly using trucks but in case of inaccessible retail outlets, supply was made through autorickshaws also. Transportation to remote places was outsourced. Lighter 200ml bottles were introduced so that more bottles could be transported to meet the growing demand. The hub-and-spoke distribution system ensured deeper penetration and faster turnaround of returnable glass bottles. It was connected by an IT system. Hubs, which were essentially super stockists and distributors in a particular area were supplied directly from the plant or the companys warehouse. They did not sub-distribute to retailers. The spoke was typically closest to the retail outlets and was serviced by a hub distributor This cost-effective arrangement allowed large loads traveling longer distances and short loads doing short distances. While the 300ml bottle had only four rotations in a year, the increased volume of 200ml bottles ensured 10-14 rotations.

Human resources development

When Short arrived in 1997, Coke had 60 employees in India. By 1999, it had risen to well over 300 at the Gurgaon headquarters alone. After the merger of bottling companies under the new plan, there was a duplication of responsibilities in marketing, sales and customer support. So, CCI decided to prune managerial positions at the upper and middle levels in the headquarters. By March 2002, about 12% of CCIs 560 managers had left. Another cause of concern was the frequent change of leadership and changing focus of the company with every change. During the period 1990-2003, Pepsi had only three CEOs while CCI had four CEOs between 1993 and 2003 (Coke had only 11 CEOs in its 114 years history). After the violation of policy norms in the North Indian operations in early 2000, Von Behr realized the need for better communication with the lower and middle management. First, he personally met finance heads in every territory to explain CCIs credit policy. Second, he issued a directive that discounting limits and best practices be strictly adhered to, regardless of market conditions. Third, he launched a major IT initiative that made the operations of the entire organization transparent. Till then, the Gurgaon HQ did not have access to accounts at other locations except for a monthly statement. But as a result of the IT initiative, at any given point in time, the HQ was able to monitor the exact financial status of its regional centers, down to the depot level. In 2001, to support the localized structure and make the CCI system more entrepreneurial, CCI introduced a detailed career planning system for its 530 managers. Rules and codes were put in place to culturally integrate people who came from the bottling acquisitions. Based on the feed back from employees, a more entrepreneurial and Indianized approach was emphasized. The strict dress code was also relaxed. The new system was individual-based, but led by market and performance. Far more autonomy was given to junior employees.

9

Hindustan Coca-Cola Bottling North West, Hindustan Coca-Cola Bottling South West, Bharat Coca-Cola North East and Bharat Coca-Cola South East. 86 Global CEO September 2003

CASE STUDY

Von Behr initiated two training programs called the Pegasus and Way Forward. While Pegasus was a means for middle level managers, Way Forward aimed on identifying future business leaders within the company. Pegasus included a four-day program with a group of 25 middle managers held at a holiday resort, where the companys future plans were communicated. The company also obtained feedback on the managers first hand experience of the market. The forum was used to remove apprehensions about the company and promote trust. Way Forward established guidelines on how CCI would nurture and develop future leaders. RGMs would meet the top management twice a year to identify fast track managers and train them for more responsible positions. Promising management trainees were sent overseas for a three-week internship. Management trainees were trained to run their units like small enterprises. An e-learning system was introduced. This initiative helped in cutting training costs. To encourage the e-learning concept, gifts were given to employees securing good scores. As part of its cost reduction drive, CCI began to benchmark its salaries to the best Indian companies instead of offering salaries in line with its international standards. Managers were asked to refrain from extravagant spending such as farmhouse accommodations and overseas trips to bottlers. Coke held back many real estate purchases like the one in Gurgaon, where it had initially planned to build a bigger building for its headquarters. Coke also put in place a succession plan, which seemed to indicate that Indian managers were at last ready to take over the mantle. Sanjiv Gupta was appointed as deputy president in 2001. In July 2003, he became the CEO and President.

The road ahead

Encouraged by the 34% volume growth in 200210, CCI planned to double the capacity at an investment of $125 mn (making India Cokes second largest investment in Asia after China $1.2 bn). The company had plans to invest in South India to broaden the product portfolio and in East India to increase its reach. CCI expected its accumulated losses to be wiped off by 2005-06. But, one major concern was that CCIs staff levels (accounting for 20% of Cokes global employee strength) still remained high compared to its international operations. Cokes initiatives for bringing the most affordable package sizes to India had given strong results. Aggressive marketing of the affordable 200ml single-serve pack had expanded the Indian market, particularly in rural areas that were home to 70% of the Indian population. But whether the growth would be sustained, was still a major question mark. Also, the efficiency of Cokes bottling operations still needed significant improvement. Among various new initiatives planned, CCI was considering the possibility of introducing its Georgia brand of Tea and Coffee at Rs. 3 and Rs. 4 respectively. Coke planned to distribute Georgia through vending machines and directly compete with street hawkers. Coke also had plans to offer value added milk products like flavored milk in association with Nestle. All these products would be outsourced from contract packers. But some analysts pointed that the non-carbonated drinks gave very lower margins, compared to the 80% margins CSDs provided.11 On the environmental front, Coke and Pepsi were facing charges of not adhering to international standards in India. In February 2003, in a study conducted by Delhi-based Center for Science and Environment (CSE) packaged water from these companies along with others was found to be carrying

10 11

Business Line, April 20, 2002. Working up a thirst to quench Asia, Far Eastern Economic Review, 1st February 2001. 87

Global CEO September 2003

Coca-Cola in India

Figure 11 The Coca-Cola company: revenues ($ bn)

4.5 4 3.5 0 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 1997 1998 1999 2001 2002 2003

Figure 12 Coke: Worldwide unit case volume by region

Africa 6% Asia 18% North America 30%

Europe, Eurasia & Middle East 22%

Latin America 24%

Source: Coca-Cola Company, Annual Report

Source: Coca-Cola Annual Report 2002

high pesticide content. It was alleged that the usage of underground water in the respective regions had led to the contamination. Pesticides used in farming had seeped into the underground water. Again in August 2003, CSE found high pesticide content in their soft drinks as well. Cokes plant in Kerala was also accused of draining away underwater resources in the region and letting out sludge containing toxic chemicals that polluted the land, water supplies and food chain12. Coke and Pepsi had strongly refuted all the charges, but they faced opposition by many social and political groups. Globally, Cokes traditional markets in North America and Europe had stagnated. CSDs were looked at as the next health threat after tobacco and fast foods. So, Coke was embarking on a regionalization and people oriented restructuring drive globally to diversify its beverage portfolio and give the local managers more opportunities to experiment with the local products. CEO Douglas Daft was closely following the Indian initiative, as he strongly believed, it would emerge as the model for the company in developing economies. Vamsi Krishna & Himansu Mahapatra They are Associate Consultants at ICFAI Knowledge Center. They can be contacted at vamsi-thoda@icfai.org and himansu@icfai.org respectively.

Reference # 15-03-09-10

References

1. 2. 3. 4.

12

George Skaria, Can Coca-Cola Bottle up the Chauhans? Business Today, August 22, 1998. George Skaria, The CEO as Cola-borator, Business Today, November 7, 1999. Dwijottam Bhattacharjee; Sandeep Joseph, Saving Coke, Businessworld, March 6, 2000. The Coca-Cola Company updates on business strategies and confirms long-term volume and EPS growth objectives, Coca-Cola Press release, April 11, 2000.

A study done by BBC Radio 4s Face The Facts presenter John Waite. Global CEO September 2003

88

CASE STUDY

5. 6. 7. 8. 9.

Coca-Cola shifts gear in India; Chauhan says Bisleri is not for sale, Business India, July 24, 2000. Suh-kyung Yoon, Working up a thirst to quench Asia, Far Eastern Economic Review, February 1, 2001. Coming Back, Business India, March 19, 2001. Generation Next, Business India, May 28, 2001. Paroma Roy Chowdhury, The Unbottling of Coke, Business Today, July 1, 2001.

10. Parul Gupta, Cokes Second Wind, Business Today, February 3, 2002. 11. Parul Gupta, Coke Posts Maiden Profits in India, Business Standard, February 8, 2002. 12. Coke Hits the Country Road in Strategic Shift, Business Standard, March 22, 2002. 13. Coca-Cola India reports 34 pc growth in Q1, Business Line, April 17, 2002. 14. Manjeet Kripalani, Rural India, Have a Coke, Business Week, May 27, 2002. 15. Government Again Rejects Coke Plea, Business India, July 22, 2002. 16. Coke to Divest 49% to Partners, Staff Fund, Business Standard, August 17, 2002. 17. Coca-Cola Uncorks New Growth Plans, Business Line, August 18, 2002. 18. Parul Gupta and Partha Ghosh, Coke Bottlers may Take Pie, Business Standard, August 20, 2002. 19. For a Good Cause, Business India, September 2, 2002. 20. Moinak Mitra, Water Wars, Business Today, September 16, 2002. 21. Coca-Cola sees India as Strong Growth Market, Business Line, October 16, 2002. 22. Coke Plans Hold Water as Kinley Spurs Growth Plans More Acquisitions, Business Line, October 18, 2002. 23. Coke Without Fizz, Business India Intelligence, November 2002. 24. Manjeet Kripalani and Mark L. Clifford, Finally, Coke Gets it Right in India, Business Week, February 10, 2003. 25. Win Some, Lose Some, Business Standard, February 22, 2003. 26. Bakshis Pepsi, Business Today, March 2, 2003. 27. Bhupesh Bhandari and Parul Gupta, Finally, Coke Gets Some Fizz, Business Standard, March 25, 2003. 28. Parul Gupta, Soft Drinks Firms on a Rural Drive to Push Sales, Business Standard, June 5, 2003. 29. Coca-Cola Annual Reports, 2002, 2001. 30. www.coke.com 31. www.indiainfoline.com 32. www.agencyfaqs.com

Global CEO September 2003 89

You might also like

- I Year LLB Exame Note For Constitution of IndiaDocument13 pagesI Year LLB Exame Note For Constitution of IndiaNaveen Kumar88% (33)

- Contract-I and Specific Relief ActDocument31 pagesContract-I and Specific Relief ActNaveen Kumar77% (22)

- PepsiDocument104 pagesPepsiritesh29369No ratings yet

- Dep 32.32.00.11-Custody Transfer Measurement Systems For LiquidDocument69 pagesDep 32.32.00.11-Custody Transfer Measurement Systems For LiquidDAYONo ratings yet

- Project Report by Sarthak Pandyaa BBA 4BDocument83 pagesProject Report by Sarthak Pandyaa BBA 4BSUMIT KUMAR PANDEY P100% (2)

- Delhi CBSE School Website and AddressDocument153 pagesDelhi CBSE School Website and AddressPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Delhi CBSE School Website and AddressDocument153 pagesDelhi CBSE School Website and AddressPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Study apparel export order processDocument44 pagesStudy apparel export order processSHRUTI CHUGH100% (1)

- Customer List for Escape ProjectDocument9 pagesCustomer List for Escape ProjectPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Banking Finance Agile TestingDocument4 pagesBanking Finance Agile Testinganil1karnatiNo ratings yet

- ResidencesDocument252 pagesResidencesPatrick Adams75% (16)

- Project On Marketing Strategies of Coca ColaDocument63 pagesProject On Marketing Strategies of Coca ColaAryan RawatNo ratings yet

- Cadbury ResearchDocument101 pagesCadbury Researchaldina augustinNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola Company Project Report AnalysisDocument77 pagesCoca-Cola Company Project Report AnalysisanuragNo ratings yet

- Sales and Distribution of Bisleri Dazzle KinleyDocument25 pagesSales and Distribution of Bisleri Dazzle KinleySunil Pal100% (1)

- ExquisiteDocument20 pagesExquisitePatrick Adams50% (2)

- Contact List with AddressesDocument27 pagesContact List with AddressesPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- FrescoDocument106 pagesFrescoPatrick Adams100% (1)

- Coca ColaDocument62 pagesCoca ColaRaman Chamber100% (2)

- Market Share of Dabur Real JuiceDocument66 pagesMarket Share of Dabur Real JuiceAazam75% (4)

- Cost Analysis Format-Exhaust DyeingDocument1 pageCost Analysis Format-Exhaust DyeingRezaul Karim TutulNo ratings yet

- Gardens IIDocument114 pagesGardens IIPatrick Adams0% (1)

- Coca-Cola's Merchandise ProductsDocument99 pagesCoca-Cola's Merchandise Productssalman100% (1)

- A Project On Marketing Mix - Coca ColaDocument68 pagesA Project On Marketing Mix - Coca ColaUday Kumar100% (2)

- Alder GroveDocument45 pagesAlder GrovePatrick Adams75% (8)

- Mhcci ListDocument1,074 pagesMhcci ListShaiwal Parashar57% (7)

- Crest ViewDocument69 pagesCrest ViewPatrick Adams67% (3)

- MOP Final List of 32 Energy Consulting FirmsDocument9 pagesMOP Final List of 32 Energy Consulting FirmsPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Bajaj AutoDocument33 pagesBajaj Autoajay89% (9)

- Unit 06 Extra Grammar ExercisesDocument3 pagesUnit 06 Extra Grammar ExercisesLeo Muñoz43% (7)

- List of Network HospitalDocument80 pagesList of Network HospitalPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Dau Terminal AnalysisDocument49 pagesDau Terminal AnalysisMila Zulueta100% (2)

- XAT 2014 SECTION C List of XAT Associate Member InstitutesDocument8 pagesXAT 2014 SECTION C List of XAT Associate Member InstitutesPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- BHEL Directory 2011Document128 pagesBHEL Directory 2011Ashok Kumar Meena100% (2)

- Project On Coca ColaDocument78 pagesProject On Coca ColaAkshay Kumar Gautam100% (1)

- Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (Eexi) : Regulatory DebriefDocument8 pagesEnergy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (Eexi) : Regulatory DebriefSalomonlcNo ratings yet

- INDIVIDUAL CUSTOMER's Account DetailsDocument36 pagesINDIVIDUAL CUSTOMER's Account DetailsPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Project On Marketing Strategies of Coca-Cola - Kanmani Bharathi (21MB029)Document30 pagesProject On Marketing Strategies of Coca-Cola - Kanmani Bharathi (21MB029)bharathiNo ratings yet

- Marketing Strategies of Coca Cola India PVT LTD - Vishal ChauhanDocument97 pagesMarketing Strategies of Coca Cola India PVT LTD - Vishal ChauhanVishal ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola in IndiaDocument16 pagesCoca-Cola in IndiaEl Mouatassim Billah SoufianeNo ratings yet

- A Report On Coca-Cola IndiaDocument11 pagesA Report On Coca-Cola IndiaAbul HasnatNo ratings yet

- Hindustan Coca - Cola Beverages Pvt. LTD., Bidadi, BangaloreDocument14 pagesHindustan Coca - Cola Beverages Pvt. LTD., Bidadi, BangaloreOM Kumar89% (9)

- A Research Project Report On "Comparative Analysis of Marketing Strategy of Nestle, Amul & Cadbury Chocolates"Document47 pagesA Research Project Report On "Comparative Analysis of Marketing Strategy of Nestle, Amul & Cadbury Chocolates"Anonymous UWMOBhDiNo ratings yet

- Thums Up Case Study on Brand History, Marketing Strategies & Future PlansDocument2 pagesThums Up Case Study on Brand History, Marketing Strategies & Future PlansDebashis DashNo ratings yet

- Project On Maaza FreshDocument78 pagesProject On Maaza Freshsharmaamit66667% (3)

- 4p Analysis of Chota CokeDocument7 pages4p Analysis of Chota CokerosbindanielNo ratings yet

- My Project On Distribution ChannelDocument52 pagesMy Project On Distribution ChannelVishal Somani0% (1)

- Project Report On Why People Prefer Coca-Cola Over Other DrinksDocument152 pagesProject Report On Why People Prefer Coca-Cola Over Other DrinksAkashdeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Case Study Coca ColaDocument6 pagesCase Study Coca ColaAndrej AndrejNo ratings yet

- Coco ColaDocument69 pagesCoco ColaAnonymous YH6N4cpuJzNo ratings yet

- Aryan Singh Coca Cola PGFB 1909 2Document11 pagesAryan Singh Coca Cola PGFB 1909 2AryanSinghNo ratings yet

- Coca - Cola: Brindavan Bottlers Pvt. Ltd. Summer Internship Report On Vertical Growth ofDocument86 pagesCoca - Cola: Brindavan Bottlers Pvt. Ltd. Summer Internship Report On Vertical Growth ofKarishma SinghNo ratings yet

- Dabur Project - 11111Document32 pagesDabur Project - 11111King Nitin Agnihotri0% (1)

- India's Thirst For Rural MarketDocument19 pagesIndia's Thirst For Rural MarketVedant VarshneyNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola Company Project Report on Brand Preferences in IndiaDocument85 pagesCoca-Cola Company Project Report on Brand Preferences in IndiaVarun RimmalapudiNo ratings yet

- Marketing Project PaperBoatDocument20 pagesMarketing Project PaperBoatAshish Gupta100% (1)

- Coca Cola's Product Portfolio and Distribution Adaptation in IndiaDocument19 pagesCoca Cola's Product Portfolio and Distribution Adaptation in IndiaRituraj Acharya100% (1)

- Coca Cola Report (PALAK)Document60 pagesCoca Cola Report (PALAK)Palak ShahNo ratings yet

- Brand Positioning of Coca ColaDocument12 pagesBrand Positioning of Coca ColaPriyanka KumariNo ratings yet

- Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Private Limited (Patna)Document74 pagesHindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Private Limited (Patna)krrish11No ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis of Tata Coffee Analyses The BrandDocument6 pagesSWOT Analysis of Tata Coffee Analyses The BrandjaganNo ratings yet

- Coka Cola ReportDocument96 pagesCoka Cola ReportDeepak Singh Rautela100% (1)

- Hero Honda's Mission, Vision, Environmental & Indusrtial AnalysisDocument40 pagesHero Honda's Mission, Vision, Environmental & Indusrtial Analysisashish67% (6)

- Research Methodology Cadbury Dairy Milk Advertisement ImpactDocument20 pagesResearch Methodology Cadbury Dairy Milk Advertisement Impactmansikothari1989100% (1)

- Future Goals of BATADocument12 pagesFuture Goals of BATAKausherNo ratings yet

- Report On Distribution Effectiveness of Cola, IndiaDocument57 pagesReport On Distribution Effectiveness of Cola, Indiamonish_shah28100% (1)

- History of Soft Drink in IndiaDocument3 pagesHistory of Soft Drink in IndiaResmi Siva50% (2)

- Executive SummaryDocument4 pagesExecutive SummaryAnonymous 22GBLsme10% (1)

- Minor Project ReportDocument24 pagesMinor Project ReportSanchit JainNo ratings yet

- Synopsis On Marketing Strategies of Coca ColaDocument11 pagesSynopsis On Marketing Strategies of Coca ColaDurgesh Singh0% (1)

- Company profile and brand history of Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) and its iconic laundry brand RinDocument3 pagesCompany profile and brand history of Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) and its iconic laundry brand Rinshahinmandaviya100% (1)

- Coca Cola Final ReportDocument70 pagesCoca Cola Final ReportRajat Kalyan08No ratings yet

- VIP Industries - ProjectDocument41 pagesVIP Industries - ProjectbimbaagroNo ratings yet

- Internship Report 1Document20 pagesInternship Report 1himmat sutharNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola Report Prepared by Manish SaranDocument61 pagesCoca-Cola Report Prepared by Manish SaranManish Saran100% (14)

- Consumer Perception Bath SoapsDocument86 pagesConsumer Perception Bath SoapsSiddharth AnandNo ratings yet

- Ims Marketing - and - Sales - Promotion - of - Red - Chief - Shoes......Document85 pagesIms Marketing - and - Sales - Promotion - of - Red - Chief - Shoes......Simran ShilvantNo ratings yet

- FMCG Sector Profile: Fast Moving Consumer GoodsDocument26 pagesFMCG Sector Profile: Fast Moving Consumer GoodsHimanshiShah100% (1)

- Comparative Analysis Between PepsiCo and Coca-Cola To Improve The Market Share and DistributionDocument42 pagesComparative Analysis Between PepsiCo and Coca-Cola To Improve The Market Share and Distributionvikas110233% (3)

- Strategic Management of CadburyDocument39 pagesStrategic Management of CadburySachi PandyaNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Coca Cola Market StrategiesDocument24 pagesProject Report On Coca Cola Market StrategiesAnonymous 2ywVRjTy3No ratings yet

- Marketing Strategies of Coca Cola: Project Report OnDocument24 pagesMarketing Strategies of Coca Cola: Project Report OnmanojNo ratings yet

- Minor Report of BhuuuumiDocument72 pagesMinor Report of BhuuuumiAnjali SharmaNo ratings yet

- Arman Alam - MPRDocument16 pagesArman Alam - MPRSiddharth ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- DONE Exams NewsPaperDocument1 pageDONE Exams NewsPaperPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Done - List of Mentors Pa Da Institution WiseDocument1 pageDone - List of Mentors Pa Da Institution WisePatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- DONE - Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith, VaranasiDocument1 pageDONE - Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith, VaranasiPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Revised Admission ScheduleDocument1 pageRevised Admission SchedulePatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- LL.B. (I, II & III Year) : Chaudhary Charan Singh University, MeerutDocument1 pageLL.B. (I, II & III Year) : Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerutdevthakur_mbaNo ratings yet

- Education Secretaries 10Document6 pagesEducation Secretaries 10Patrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Theories of Punishments - LLB I YEARDocument12 pagesTheories of Punishments - LLB I YEARNaveen Kumar0% (1)

- Most Recent US Arrival Date and in What StatusDocument2 pagesMost Recent US Arrival Date and in What StatusPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Done - Keonics Centre AddressDocument44 pagesDone - Keonics Centre AddressPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- MbaDocument20 pagesMbaPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- VSNDocument7 pagesVSNPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Untitled 1Document230 pagesUntitled 1Sakunthala MuthuNo ratings yet

- Direct FileActDocument17 pagesDirect FileActTAPAN TALUKDARNo ratings yet

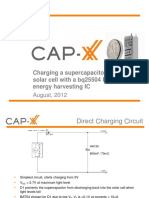

- 1208 CAP XX Charging A Supercapacitor From A Solar Cell PDFDocument12 pages1208 CAP XX Charging A Supercapacitor From A Solar Cell PDFmehralsmenschNo ratings yet

- Tutorial: Energy Profiles ManagerDocument6 pagesTutorial: Energy Profiles ManagerDavid Yungan GonzalezNo ratings yet

- HTTP://WWW - Authorstream.com/presentation/kunalcmehta 1123128 Exim PolicyDocument2 pagesHTTP://WWW - Authorstream.com/presentation/kunalcmehta 1123128 Exim PolicyPranesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal: Retail Environment Design To Create Brand ExperienceDocument3 pagesProject Proposal: Retail Environment Design To Create Brand ExperienceMithin R KumarNo ratings yet

- MCQ 14 Communication SystemsDocument21 pagesMCQ 14 Communication SystemsXeverus RhodesNo ratings yet

- IPR GUIDE COVERS PATENTS, TRADEMARKS AND MOREDocument22 pagesIPR GUIDE COVERS PATENTS, TRADEMARKS AND MOREShaheen TajNo ratings yet

- Refractomax 521 Refractive Index Detector: FeaturesDocument2 pagesRefractomax 521 Refractive Index Detector: FeaturestamiaNo ratings yet

- Objective Type Questions SAPMDocument15 pagesObjective Type Questions SAPMSaravananSrvn77% (31)

- Ade.... Data Analysis MethodsDocument2 pagesAde.... Data Analysis MethodszhengNo ratings yet

- z2OrgMgmt FinalSummativeTest LearnersDocument3 pagesz2OrgMgmt FinalSummativeTest LearnersJade ivan parrochaNo ratings yet

- Acuite-India Credit Risk Yearbook FinalDocument70 pagesAcuite-India Credit Risk Yearbook FinalDinesh RupaniNo ratings yet

- Integrated Building Management Platform for Security, Maintenance and Energy EfficiencyDocument8 pagesIntegrated Building Management Platform for Security, Maintenance and Energy EfficiencyRajesh RajendranNo ratings yet

- Depreciation Methods ExplainedDocument2 pagesDepreciation Methods ExplainedAnsha Twilight14No ratings yet

- Oteco 3Document12 pagesOteco 3VRV.RELATORIO.AVARIA RELATORIO.AVARIANo ratings yet

- Imantanout LLGDDocument4 pagesImantanout LLGDNABILNo ratings yet

- Training and Development Project Report - MessDocument37 pagesTraining and Development Project Report - MessIqra Bismi100% (1)

- Index: Title Page Acknowledgement Chapter 1: ProfilesDocument43 pagesIndex: Title Page Acknowledgement Chapter 1: ProfilesRaushan singhNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument4 pagesReportapi-463513182No ratings yet

- Brexit Essay - Jasraj SinghDocument6 pagesBrexit Essay - Jasraj SinghJasraj SinghNo ratings yet

- 2018 Price List: Account NumberDocument98 pages2018 Price List: Account NumberPedroNo ratings yet

- Lilypad Hotels & Resorts: Paul DidriksenDocument15 pagesLilypad Hotels & Resorts: Paul DidriksenN.a. M. TandayagNo ratings yet

- Mr. Arshad Nazer: Bawshar, Sultanate of OmanDocument2 pagesMr. Arshad Nazer: Bawshar, Sultanate of OmanTop GNo ratings yet