Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of GMP Regulations

Uploaded by

Dhea 'Chiu' SamanthaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of GMP Regulations

Uploaded by

Dhea 'Chiu' SamanthaCopyright:

Available Formats

History of GMP

Good Manufacturing Practice resulted from a long history of the need for consumer protection. GMPs are regulations issued by authority of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. To understand why they are the way they are, it is useful to look back at the history of FDA legislation and consumer protection issues.

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were no federal regulations to protect the public from dangerous products, and technology was primitive. The move from an agricultural to an industrial society meant that people were getting their food from sources further away. Conditions in food and drug industries would be unthinkable today. Ice was the main means of refrigeration, milk was unpasteurized. Chemical preservatives and toxic colors were uncontrolled. Medicines containing opium, morphine, heroin, and cocaine were sold without restriction and labeling did not indicate their presence. In 1903, Harvey W. Wiley, a chemist with the US Department of Agriculture and crusader for safer products, established a volunteer "Poison Squad." The young men who joined him agreed to eat only foods treated with measured amounts of chemical preservatives (including borax, formaldehyde and salicylic, sulphurous and benzoic acids) to determine whether or not they were injurious to health. The Poison Squad became a national sensation and raised awareness regarding the need for food safety. In 1906, Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a graphic exposure of the meatpacking industry. Public outcry resulting from filthy conditions described in this book pushed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This act prohibited the interstate transport of unlawful food and drugs under penalty of seizure of the products and/or prosecution of the responsible parties. The basis of the law rested on the regulation of product labeling rather than pre-market approval. Drugs could not be sold in any other condition unless the specific variations from USP and National Formulary standards were plainly stated on the label. The food law prohibited the addition of any ingredients that would substitute for the food, conceal damage, pose a health hazard, or constitute a filthy or decomposed substance. If the manufacturer opted to list the weight or measure of a food, this had to be done accurately. Also, the food or drug label could not be false or misleading in any particular, and the presence and amount of eleven dangerous ingredients, including alcohol, heroin, and cocaine, had to be listed. While this law was a great step forward, it nonetheless left gaps in consumer protection. It allowed the government to take non-compliant companies to court, but did not allow for proactive compliance requirements. Labels were not required to state weight or measure - it was only required that a contents statement, if used be truthful. Even after amendments to the law outlawing false therapeutic claims, a defendant only needed to show that he personally believed in his fake remedy to escape legal consequences. Congress, however, refused to take action until a tragedy that took the lives of over 100 people (mostly children) occurred.

Elixir Sulfanilamide

Sulfanilamide is a drug used to treat streptococcal infections, and was produced in powder and tablet form. Because children often needed to take the drug for sore throats, the S.E. Massengill Company developed a liquid form of this drug. They tested it for flavor, appearance, and fragrance, and found it acceptable. They sent out 633 shipments in September of 1937. They soon found out that many people who took this drug were dying terrible deaths of kidney failure and experiencing stoppage of urine, severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, stupor, and convulsions. Many of the victims were children. The chemists at Massengill had used a toxic chemical to dissolve the solid sulfanilamide into a liquid. They used diethylene glycol, a chemical normally used as an anti-freeze. At the time, there were no requirements that drugs be tested for safety. Massengill was only charged with a minor labeling infraction, calling the medicine an "elixir" when it had no alcohol in it. Massengill refused to take responsibility for the deaths, but the head chemist who developed the drug committed suicide.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

In 1937 when this tragedy occurred, the Senate had introduced a bill to overhaul the 1906 law, but congressional action had stalled. As a response to the tragedy, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was passed in 1938. It required that drug manufacturers show that a drug is safe before marketing it. Other provisions of this act include that cosmetics and therapeutic devices were regulated for the first time; proof of fraud was no longer required to stop false claims for drugs; poisonous substances in foods became regulated; authority was granted to FDA to inspect factories; and federal court injunctions were added as an allowable legal remedy.

Thalidomide

In the years leading up to the thalidomide incident, Senator Estes Kefauver held hearings on drug costs, the state of science supporting drug effectiveness, and claims made in advertising and labeling. Despite disturbing findings, Congress once again did not pass legislation until a near tragedy struck. This time tragedy was avoided due to the diligence of a woman by the name of Frances Oldham Kelsey. She was a PhD in pharmacology working for FDA. While she was a faculty member at the University of Chicago she had worked on finding a cure for malaria, and during her studies had learned that some drugs pass through the placenta during pregnancy. One of her first assignments at FDA was to review an application from Richardson Merrill for the the tranquilizer and painkiller thalidomide. It was also used in pregnant women for morning sickness. Despite the fact that thalidomide was approved in Canada and many countries in Europe and Africa, Kelsey withheld approval and requested additional studies because she was concerned about the drug's impact on the nervous system. Around the same time, many babies starting being born with severe deformities in Europe and other places. When these deformities were eventually traced to the use of thalidomide during pregnancy, Kelsey became a hero for keeping thalidomide of the US market.

The Drug Amendments of 1962

Because of the high profile nature of the thalidomide incident, public opinion pushed Congress to unanimously pass the Drug Amendments of 1962. These Amendments tightened control over prescription drugs, new drugs and investigational drugs. Effectiveness now had to be shown before a drug would be approved, drug firms were required to send adverse reaction reports to FDA, and drug advertising in medical journals was required to provide complete information to doctors (risks as well as benefits.) And most significantly for this article, The Drug Amendments of 1962 formalized Good Manufacturing Practices. In the years since 1962 many laws have been passed which impact GMP and how FDA carries out its mission. Stricter labeling requirements came in 1966 when the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act required all consumer products in interstate commerce to be honestly and informatively labeled, with FDA enforcing this for food, drugs, cosmetics, and medical devices. Anti-tampering regulations came about in 1983 after seven people in Chicago died after taking Tylenol laced with cyanide.

Conclusion

The GMP regulations grew out of legislation passed because terrible tragedies either killed many people, or almost did. GMP ensures that the medical products we use are safe, pure, and effective. Everyone who works in the life science industry is responsible to ensure that their organization's products do not harm the customer, and that they do what they are supposed to do. If you were using your own product, wouldn't you want it to be manufactured according to the strictest of standards?

http://themasteryinstitute.org/gmpmastery/history.htm

You might also like

- Loimologia: Or, an Historical Account of the Plague in London in 1665 With Precautionary Directions Against the Like ContagionFrom EverandLoimologia: Or, an Historical Account of the Plague in London in 1665 With Precautionary Directions Against the Like ContagionNo ratings yet

- Patient ZeroDocument109 pagesPatient ZeroDiego Emanuel Osechas LucartNo ratings yet

- Pentagon Military Analysts Program Documents Obtained by The New York Times: Documents Released On 4/30/08: Part 1Document720 pagesPentagon Military Analysts Program Documents Obtained by The New York Times: Documents Released On 4/30/08: Part 1CREWNo ratings yet

- Progressive Era DBQDocument5 pagesProgressive Era DBQbcpxoxoNo ratings yet

- 2023-04-20 JDJ MT To Blinken Re Public Statement On Hunter Biden EmailsDocument5 pages2023-04-20 JDJ MT To Blinken Re Public Statement On Hunter Biden EmailsWashington ExaminerNo ratings yet

- History of The United States, Vol. I (Of VI) by Andrews, Elisha Benjamin, 1844-1917Document211 pagesHistory of The United States, Vol. I (Of VI) by Andrews, Elisha Benjamin, 1844-1917Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Peter Navarro Memo - February 23, 2020Document4 pagesPeter Navarro Memo - February 23, 2020Eric L. VanDussenNo ratings yet

- The Infodemic' of COVID-19 Misinformation, ExplainedDocument4 pagesThe Infodemic' of COVID-19 Misinformation, Explainedcharanmann9165No ratings yet

- AG-#1189286-V1-FINAL Complaint Injunctive Relief Kemp V Bottoms With ExhibitsDocument124 pagesAG-#1189286-V1-FINAL Complaint Injunctive Relief Kemp V Bottoms With ExhibitsFox NewsNo ratings yet

- FAU Issues Email About Suspicious ManDocument1 pageFAU Issues Email About Suspicious ManMichelle SolomonNo ratings yet

- Coast Magazine (05-06-2010)Document40 pagesCoast Magazine (05-06-2010)Carolina Media ServicesNo ratings yet

- Designed-Or-Evolved. Bombardier BeetleDocument33 pagesDesigned-Or-Evolved. Bombardier Beetle300rNo ratings yet

- Filed Order EQCE087085Document14 pagesFiled Order EQCE087085Local 5 News (WOI-TV)No ratings yet

- Fairstein V NetflixDocument119 pagesFairstein V NetflixTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Trump Emoluments Subpoenas (2 of 2)Document237 pagesTrump Emoluments Subpoenas (2 of 2)FindLawNo ratings yet

- Gun Owners of America v. GarlandDocument23 pagesGun Owners of America v. GarlandCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- 1.12 Letter To State Dept. On IOM Travel LoansDocument3 pages1.12 Letter To State Dept. On IOM Travel LoansFox NewsNo ratings yet

- Report - The Devastating Costs of DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas' Open Borders PoliciesDocument82 pagesReport - The Devastating Costs of DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas' Open Borders PoliciesDaily Caller News Foundation100% (1)

- Biological EspionageDocument3 pagesBiological EspionageSasiii SoniiiNo ratings yet

- 2016.11.23 Responsive Records - Part 6Document87 pages2016.11.23 Responsive Records - Part 6DNAinfoNewYorkNo ratings yet

- NYT Defamation Case Over Reports on Project Veritas VideoDocument16 pagesNYT Defamation Case Over Reports on Project Veritas VideoMateo RuizNo ratings yet

- Senate Bill 184Document11 pagesSenate Bill 184Mike CasonNo ratings yet

- Oathkeepers: Government's Supplemental Brief On 18 USC Sec. 1512c2Document38 pagesOathkeepers: Government's Supplemental Brief On 18 USC Sec. 1512c2Patriots Soapbox InternalNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ron Polland: How I Made Obama's Long Form Birth CertificateDocument59 pagesDr. Ron Polland: How I Made Obama's Long Form Birth CertificateObamaRelease YourRecords100% (2)

- DOJ Torture Interrogation Memo From Alberto Gonzales To The President: Disbar Torture LawyersDocument50 pagesDOJ Torture Interrogation Memo From Alberto Gonzales To The President: Disbar Torture LawyersdisbartorturelawyersNo ratings yet

- Open Letter From Some Members of The Illinois Law Faculty July 2009Document9 pagesOpen Letter From Some Members of The Illinois Law Faculty July 2009Chicago Tribune100% (2)

- Campus Crime: Compliance and Enforcement Under The Clery ActDocument70 pagesCampus Crime: Compliance and Enforcement Under The Clery ActScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Nadler NSBDocument4 pagesNadler NSBMichael GinsbergNo ratings yet

- Natalie Abruzzo: BroadcastDocument1 pageNatalie Abruzzo: Broadcastnabruzzo1No ratings yet

- If You'Re Queer and You'Re Not Angry in 1992 You'Re Not Paying Attention Mother JonesDocument15 pagesIf You'Re Queer and You'Re Not Angry in 1992 You'Re Not Paying Attention Mother Jonesletters2myselfNo ratings yet

- Tennessee Attorney General Letter On McKamey Manor Haunted HouseDocument2 pagesTennessee Attorney General Letter On McKamey Manor Haunted HouseUSA TODAY Network100% (1)

- 2.6.14 OCE ComplaintDocument8 pages2.6.14 OCE ComplaintTrue The VoteNo ratings yet

- Police Benevolent Asso V Police Benevolent Asso Petition 1Document18 pagesPolice Benevolent Asso V Police Benevolent Asso Petition 1Matt TroutmanNo ratings yet

- Flynn Lawsuit Versus Jan 6Document80 pagesFlynn Lawsuit Versus Jan 6Daily KosNo ratings yet

- Biden Admin Pressed Over 85,000 Unaccounted For Migrant Children Released Into USDocument2 pagesBiden Admin Pressed Over 85,000 Unaccounted For Migrant Children Released Into USJoeSchoffstallNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of The Isle of Wight 1886Document195 pagesDictionary of The Isle of Wight 1886George Brannon100% (1)

- Class Action Lawsuit Against LuLaRoeDocument13 pagesClass Action Lawsuit Against LuLaRoeKATU Web StaffNo ratings yet

- Dl2011 Bioethics LegislationDocument36 pagesDl2011 Bioethics Legislationjeff_quinton5197No ratings yet

- Letter To FDA From Members of CongressDocument3 pagesLetter To FDA From Members of CongressWJLA-TVNo ratings yet

- Sierra Club V WeitsmanDocument50 pagesSierra Club V WeitsmanrkarlinNo ratings yet

- 1973 CIA Report On Its Relationship With The USAID Office of Public SafetyDocument7 pages1973 CIA Report On Its Relationship With The USAID Office of Public SafetyAndresNo ratings yet

- Countless Killed Because Hospitals Followed Deadly Chinese Treatment Advice Are Being Counted As COVID-19 DeathsDocument8 pagesCountless Killed Because Hospitals Followed Deadly Chinese Treatment Advice Are Being Counted As COVID-19 DeathsBursebladesNo ratings yet

- De Don Kulick - The Gender of Brazilian Transgendered ProstitutesDocument13 pagesDe Don Kulick - The Gender of Brazilian Transgendered ProstitutesAndres Felipe CastelarNo ratings yet

- Cobalt-60: Uses, Safety, and Properties of the Radioactive IsotopeDocument5 pagesCobalt-60: Uses, Safety, and Properties of the Radioactive IsotopeSa ReNo ratings yet

- Donald Trump Indicted Over Election InterferenceDocument45 pagesDonald Trump Indicted Over Election InterferenceDavid CaplanNo ratings yet

- ManafortDocument173 pagesManafortmaganwNo ratings yet

- PA Election Lawsuits TimelineDocument1 pagePA Election Lawsuits TimelineJessica WongNo ratings yet

- Bill & Hillary Clinton - The RecountDocument678 pagesBill & Hillary Clinton - The RecountchovsonousNo ratings yet

- FEC Complaint Against Biden For President, The Biden Victory Fund, The Biden Action Fund, and The DNCDocument123 pagesFEC Complaint Against Biden For President, The Biden Victory Fund, The Biden Action Fund, and The DNCKaelan DeeseNo ratings yet

- Dem Fact Sheet MemoDocument4 pagesDem Fact Sheet MemoDanny Chaitin100% (2)

- Coronavirus Intentionally Released, Chinese Govt Leading Misinformation Campaign - DR Le-Meng Yan - Interview - Coronavirus Outbreak NewsDocument9 pagesCoronavirus Intentionally Released, Chinese Govt Leading Misinformation Campaign - DR Le-Meng Yan - Interview - Coronavirus Outbreak NewsWillSmathNo ratings yet

- Doug Jensen Federal Criminal Complaint 1610486173Document4 pagesDoug Jensen Federal Criminal Complaint 1610486173Nick WeigNo ratings yet

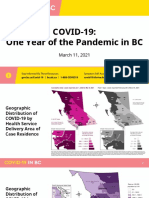

- COVID-19 Modelling in B.C.Document30 pagesCOVID-19 Modelling in B.C.CTV VancouverNo ratings yet

- Govt Response To Pezzola Motion For Mistrial RE 1776 ReturnsDocument7 pagesGovt Response To Pezzola Motion For Mistrial RE 1776 ReturnsDaily KosNo ratings yet

- Election Review - CCCIIDocument2 pagesElection Review - CCCIIAnonymous Qn8AvWvxNo ratings yet

- Mimh Otc Timeline IIDocument5 pagesMimh Otc Timeline IInaren23No ratings yet

- Drug Act USADocument54 pagesDrug Act USAsanjivNo ratings yet

- Sugar The Bitter Truth ADocument4 pagesSugar The Bitter Truth AFlorentino Rodriguez ChaviraNo ratings yet

- MSDSDocument4 pagesMSDSDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- TDS PE91 (Sama DGN Euxyl PE9010) ENGDocument3 pagesTDS PE91 (Sama DGN Euxyl PE9010) ENGDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- MRP and Inventory Policy SummaryDocument4 pagesMRP and Inventory Policy Summarynick599No ratings yet

- Euxyl PE 9010 Englisch PDFDocument6 pagesEuxyl PE 9010 Englisch PDFDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- TDS PE91 (Sama DGN Euxyl PE9010) ENGDocument3 pagesTDS PE91 (Sama DGN Euxyl PE9010) ENGDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Boy's Unpleasant Bike Riding LessonDocument1 pageBoy's Unpleasant Bike Riding LessonDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Drug Regulation in ThailandDocument43 pagesDrug Regulation in ThailandDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Euxyl PE 9010 Englisch PDFDocument6 pagesEuxyl PE 9010 Englisch PDFDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Fearless JohnDocument1 pageFearless JohnDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- MaskDocument1 pageMaskDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Korean Word SlangDocument1 pageKorean Word SlangDhea 'Chiu' SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Iran's Expanding Militia Army in IraqDocument38 pagesIran's Expanding Militia Army in IraqUbunter.UbuntuNo ratings yet

- Hacienda Luisita Case Overturned Stock Distribution PlanDocument3 pagesHacienda Luisita Case Overturned Stock Distribution PlanThea Thei YaNo ratings yet

- TN Haj Committee - List of Qurrah Provisional CoversDocument25 pagesTN Haj Committee - List of Qurrah Provisional CoverskayalonthewebNo ratings yet

- Ever Faithful by David SartoriusDocument43 pagesEver Faithful by David SartoriusDuke University PressNo ratings yet

- Memo Ki MaaDocument10 pagesMemo Ki MaaSomya AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Climate Change & Astrology (ကမ္ဘာ့ရာသီဥတုနှင့် ဗေဒင်ပညာ)Document4 pagesClimate Change & Astrology (ကမ္ဘာ့ရာသီဥတုနှင့် ဗေဒင်ပညာ)Htwe AungNo ratings yet

- CH 4 Urban Amerca Unit PlanDocument23 pagesCH 4 Urban Amerca Unit Planapi-317263014No ratings yet

- Equality Impact Assesment Milson RoadDocument5 pagesEquality Impact Assesment Milson RoadMasbro CentreNo ratings yet

- Proclamation of Independence, 17 April 1971: East West University GEN 226 / Lecture 17Document11 pagesProclamation of Independence, 17 April 1971: East West University GEN 226 / Lecture 17Md SafiNo ratings yet

- Organizational Culture and Change: Chapter 10, Nancy Langton and Stephen P. Robbins, Fundamentals of OrganizationalDocument45 pagesOrganizational Culture and Change: Chapter 10, Nancy Langton and Stephen P. Robbins, Fundamentals of OrganizationalAnuran BordoloiNo ratings yet

- Alton Eskridge v. Hickory Springs Manufacturing, 4th Cir. (2012)Document3 pagesAlton Eskridge v. Hickory Springs Manufacturing, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Malala Yousafzai Becomes Honorary CanadianDocument7 pagesMalala Yousafzai Becomes Honorary Canadiannatsukashii00No ratings yet

- International Womens Day 2014 Detailed ProgrammeDocument4 pagesInternational Womens Day 2014 Detailed ProgrammestewietunnyNo ratings yet

- Verbal Abuse II PDFDocument2 pagesVerbal Abuse II PDFiuliamaria94100% (1)

- Administrative and Staff Employee Grievance PolicyDocument3 pagesAdministrative and Staff Employee Grievance PolicyClinton Day100% (1)

- Flaviano Mejia vs. Pedro Balolong: Government, and Not The City As An Entity. The Word 'Organize' Means 'To Prepare (TheDocument2 pagesFlaviano Mejia vs. Pedro Balolong: Government, and Not The City As An Entity. The Word 'Organize' Means 'To Prepare (TheShierii_ygNo ratings yet

- Expanded Homicide Data Table 3 Murder Offenders by Age Sex and Race 2015Document1 pageExpanded Homicide Data Table 3 Murder Offenders by Age Sex and Race 2015Lê Chấn PhongNo ratings yet

- Code of EthicsDocument8 pagesCode of EthicsviorelNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines: Motion Nunc Pro TuncDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines: Motion Nunc Pro TuncArzel Tom L. BarrugaNo ratings yet

- First Nations Strategic Bulletin August-Oct 14Document20 pagesFirst Nations Strategic Bulletin August-Oct 14Russell Diabo100% (1)

- Journal Article PhoebeDocument20 pagesJournal Article PhoebeAnonymous 4yc7LNWCB9100% (1)

- B52 Lake, Hồ Hữu TiệpDocument4 pagesB52 Lake, Hồ Hữu TiệpNgô ThảoNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Public AdministrationDocument7 pagesNature and Scope of Public AdministrationBORIS ODALONUNo ratings yet

- 07-Oktober-2019 - Kompetensi Konselor Abad 21-MunginDocument28 pages07-Oktober-2019 - Kompetensi Konselor Abad 21-MunginLyanksNo ratings yet

- Rinchin - Main Points HighlightedDocument5 pagesRinchin - Main Points HighlightedAniruddha PatilNo ratings yet

- New Health Insurance Options in Indonesia ExplainedDocument21 pagesNew Health Insurance Options in Indonesia ExplainedAulia Rahmat PaingNo ratings yet

- Assignment 6 1Document4 pagesAssignment 6 1api-239946853No ratings yet

- Chairman Gary Von Stange Email CommentsDocument2 pagesChairman Gary Von Stange Email CommentsNicoleNo ratings yet

- FIM Summary of Bank Companies ActDocument6 pagesFIM Summary of Bank Companies ActafridaNo ratings yet

- Liberty Index 2022 - RLC Scorecard For US SenateDocument7 pagesLiberty Index 2022 - RLC Scorecard For US SenateRepublicanLibertyCaucusNo ratings yet