Professional Documents

Culture Documents

U.S. Constitution Amendment

Uploaded by

mdaveryCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

U.S. Constitution Amendment

Uploaded by

mdaveryCopyright:

Available Formats

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt U.S.

Constitution Amendment The Amendment That Never Existed

Introduction Welcome to U.S. Constitution, The Amendment That Never Existed A Historical Introduction To The U.S. Constitution 14th Amendment The Flow of Events The flow of events started shortly after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. The Congress proposed the first Civil Rights Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27, Ch. 31) and immediately the Congress feared that this Act would be challenged and found unconstitutional, especially when the US Supreme Court had recently ruled in the Dred Scott v. Sanford, (19 How. 404, 15 L.Ed. 691) case that the Constitution of the United States does not allow a Negro the ability to obtain the status of citizen. Before the ink was dry on this Act of Congress; the Congress thought it best to amend the Constitution for the United States so as to give the Negro the status of citizenship but immediately ran into more problems. The northern members of Congress had serious doubts that they could trust any delegation from the southern States to vote on such a resolution so they refused to allow them to be seated in Congress. Furthermore, the Senate expelled John P. Stockton of New Jersey from the Senate Chambers for casting a negative vote on the Joint Resolution which denied the U.S. Senate of the required 2/3rd votes in adopting Resolutions to amend the U.S. Constitution. [see New Jersey Joint Resolution No. 1 {Pg. 44, Paragraph 5} certified by Secretary of State of New Jersey on March 27th, 1868]. With a recount, the U.S. Senate obtained the required number of votes. If this was not bad enough; the Congress seriously doubted that the President would give his approbation (and for fear of not being able to muster enough votes for an over-ride of a Presidential Veto); the Congress did not pass the resolution on to the President of the United States as required by Article I, Section 7, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution. Over the objection of the President of the United States and the objections of the southern States; the Congress submitted the 14th Amendment to the States for ratification which included the ten southern States. Although there were some northern States that rejected the 14th Amendment; the southern States rejected the Amendment as well. With the non-ratification votes of the southern States; the ratification of the 14th Amendment failed. The members of Congress were furious! With blind rage they placed the southern States under military rule via the enactment of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867-68 for the purpose of forcing each of those southern States to ratify the 14th Amendment. To accomplish their demands; the Congress declared that they had authority to grant the Negro of the southern States the rights of suffrage to cast votes and the political rights to hold Public Offices of a southern State. This was a most interesting period of time in our history. Before the ink was dry on the U.S. Secretary of State's Proclamation declaring that the 14th Amendment to be (purportedly) ratified; the Congress again had serious doubts that the 14th Amendment granted Congress any power to declare that the newly created Negro citizen of the United States had political rights of suffrage to cast votes. The Congress immediately adopted a Resolution to amend the Constitution for the United States and that Amendment is now known as the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution. [Note: The 15th Amendment is not a grant of "Political Rights" for Negroes to hold "Public Offices" of the Untied States.]. Page 1

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt The Reconstruction Acts Several Reconstruction Acts were passed by the U.S. Congress after the Civil War was proclaimed by the President of the United States to be at an end. (Presidential Proclamation No. 153 of April 2, 1866 and 14 Stat. 814). The Reconstruction Acts that will be addressed are those that were passed on March 2, 1867 (14 Stat. 428 Ch. 153) and on July 19, 1867 (15 Stat. 14 Ch. 30). It is obvious that these Reconstruction Acts were enacted into law over the Veto of the President for the purpose of expanding the authority of Congress over the People and the States. The following sections of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 admits that the purpose of those Acts was to coerce the southern States into rescinding their vote of rejection regarding the ratification of the 14th Amendment: 1) Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867 (14 Stat. 428) at Section 5 reads: ... and when said State, by a vote of its legislature elected under said constitution (state), shall have adopted the amendment to the Constitution of the United States, proposed by the Thirty-Ninth Congress, and Known as article fourteen, and when said article shall have become a part of the Constitution of the United States, said State shall be declared entitled to representation in Congress, ... [Emphasis added] 2) And the Act of June 25, 1868 (15 Stat. 73, Chap. 70) to admit the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, to representation in Congress at Section 1 reads: That each of the States of (naming them) shall be entitled and admitted to representation in Congress as a State of the Union when the legislature of such State shall have duly ratified the amendment to the Constitution of the United States proposed by the Thirty-ninth Congress, and known as the article fourteen, [Emphasis added] 3) And the Act of March 30, 1870 (FORTY-FIRST CONGRESS, Sess. II, Chap. 39) admitting the State of Texas to Representation in the Congress of the United States reads at the Preamble: Whereas the people of Texas have framed and adopted a constitution of State government which is republican; and whereas the legislature of Texas elected under said constitution has ratified the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution of the United States; and whereas the performance of these several acts in good faith IS A CONDITION PRECEDENT TO THE REPRESENTATION OF THE STATE IN CONGRESS: [Emphasis added] Suffrage Of The Negro Under the Reconstruction Acts of 1867; the following mandates of Congress appears to be unconstitutional as follows: That when the people of anyone of said rebel States shall have formed a constitution of government in conformity with the Constitution of the United States in all respects, FRAMED BY A CONVENTION OF DELEGATES elected by the male citizens of said State twenty one years old and upward, OF WHATEVER RACE, COLOR, or previous condition, ... [Emphasis added] This paragraph appears in Section 5 of the Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867 and it declares that the electors are to be the male citizens of said State of WHATEVER RACE or COLOR. Because the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution DID NOT EXIST at the time the Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867 was enacted into law; the Congress Page 2

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt had no authority to issue a mandate that authorized any person other than White Caucasian Male Citizens to vote at an election. Even if the 14th Amendment was in effect at the time the Reconstruction Acts went into effect; the 14th Amendment granted no authority to Congress to grant any Negro the Rights of Suffrage to cast "Votes" or hold "Political Offices." The indication of this fact appears in President Andrew Johnsons Veto message regarding the passage of the first Civil Rights Bill known as 14 Stat. 27, Ch. 31. This Veto message appears in THE CONGRESSIONAL GLOBE of March 27, 1866 at S.p. 1679-81: ... If it be granted that Congress can repeal all State laws discriminating between whites and blacks in the subjects covered by this bill, why, it may be asked, may not Congress repeal, in the same way, all State laws discriminating between the two races on the subjects of suffrage and office? If Congress can declare by law who shall hold lands, who shall testify, who shall have capacity to make a contract in a State, then Congress can by law also declare who, without regard to color or race, shall have the right to sit as a juror or as a judge, to hold any office, and, finally, to vote, 'in every State and Territory of the United States.' This part of the Veto message caused considerable debate among the Members of Congress. This debate didn't cease with the Civil Rights Bill, but was carried on during the debate on the 39th Congress' Senate Resolution No. 30 and the 39th Congress' House Resolutions No's. 48, 63, and 127 proposing the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Congress felt that neither the Civil Rights Act of 1866 nor any of the Resolutions proposing the 14th Amendment granted any Negro the Rights of Suffrage within the boundaries of any State. This fact is evident not only by the debates of Representative Ashley (Congressional Globe, December 10, 1867, H.p. 117-18) and Senator Cragin (Congressional Globe, January 27, 1868, S.p. 850-51) on the 14th and 15th Amendments; but when it was first raised in the debates on the Civil Rights Acts of the THIRTY NINTH CONGRESS, Sess. I. CH. 31 of April 9, 1866 (see 42 USC 1981-86): Mr. WILSON, of Iowa. I move to add the following as a new section:

AND IT BE FURTHER ENACTED, That nothing in this act shall be so construed as to affect the laws of any State concerning the right of suffrage. Mr. Speaker, I wish to say one word. That section will not change my construction of the bill. I do not believe the term 'civil rights' includes the right of suffrage. Some gentlemen seem to have some fear on that point. The amendment was agreed to. [Emphasis added]

U.S. House debate on Senate Bill No. 61 39th Congress, 1st Session - March 2, 1866 Before this Civil Rights Act of Congress was passed into law, the Congress had decided that this Act would be challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court and that the Court would have struck it down as being unconstitutional. To head off the problem, the Congress began drafting the Resolutions proposing the 14th Amendment: [Mr. ROGERS] Why, sir, the proposed amendment of the Constitution [14th Amendment] which has just been discussed in this House and postponed till April next, was offered by the learned gentleman from Ohio [Mr. Bingham] for the very purpose of avoiding the difficulty which we are now meeting in the attempt to pass this bill [Civil Rights Act of 1866] now under consideration. Because the amendment which he reported from the committee of fifteen was intended to confer upon Congress the power to make laws which shall be necessary and proper to secure to the citizens of each State all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States, and to all persons in the several States equal protection in the right of life, liberty, and property. There is no protection or law provided for in that constitutional amendment which Congress is authorized to pass by virtue of that constitutional Page 3

amendment that us. Therefore the opinion of WHAT THIS BILL LAW.

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt is not contained in this proposed act of Congress which is now before we have the opinion of the majority of' the committee of fifteen, and the learned gentleman from Ohio, [Mr. Bingham,] THAT IN ORDER TO DO PROPOSES, CONGRESS MUST BE EMPOWERED BY AN AMENDMENT TO THE ORGANIC

I affirm, without the fear of successful contradiction, that by the decision of the highest court of the United States, that august tribunal to whose decisions every honest and patriotic man is bound to bow, it has been expressly and solemnly decided, after the most mature deliberation, by a bench of the most enlightened and learned lawyers that ever sat upon it, that negroes in this country, whether free or slave, are not citizens or people of the United States within the meaning of the words of the constitution, and that therefore no law of Congress or of any State can extend to the negro race, in the full sense of the term, the STATUS of citizenship. And the organic law, by its letter and spirit, and in view of the contemporaneous circumstances under which it was passed, fully vindicate the authority of this decision of the Supreme Court, declaring that no power within any State, much less in the Congress of the United States, can change the STATUS of the negro. That cannot be done until the requisite amendment is made to the Constitution, until some such article has been carried into effect by two thirds of both Houses of Congress and three fourths of the States. Now, sir, no bill has been offered in this House or in the other, the freedman's bill not exclude, which proposes to give to Congress such dangerous powers over the liberties of the people as this bill under consideration, and if it can be constitutionally passed by the Congress of the United States, and is no infringement upon the reserved or undelegated powers of the States, then Congress has the right, not only to extend all the rights and privileges to colored men that are enjoyed by white men, but has the right to take away. If Congress has the right to extend the great privileges of citizenship, which heretofore have been controlled by the States, to any class of beings, they have the right, by the same authority to take away from any class of people in any State the same rights that they have the right to extend to another class of persons in the same State. In other words, if the Congress has power under our present organic law to decide what rights and privileges shall be extended to negroes, it has the same power and authority under that organic law to extend its legislation so as to take away the most inestimable and valuable rights of the white men and the white women of this country, and not only take away, but destroy every blessing of life, liberty, and property, upon the principle that Congress has unlimited sovereign power over the rights of the States; and whenever, in its judgment, it may see fit, it may carry this power on to an unlimited extent. Now sir, is there any member on the either side of the House who, on the honor of a man of conscience and integrity, can make himself believe that this Congress has the right to control the privileges and immunities of every citizen of these States, as contemplated in the bill, without a change in the organic law of the land? [Emphasis added] U.S. House debate on Senate Bill No. 61 39th Congress, 1st Session - March 1, 1866 As we can see from the above speech of US Representative Rogers; the 14th Amendment does no more than what was proposed in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and therefore the 14th Amendment cannot and it does not run to the subject of Suffrage. Shortly before the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was purportedly to have been ratified by three-fourths of the States on July 9, 1868; the Congress submitted House Resolution No. 364 of the 40th Congress, 3rd Session (January 11, 1869) proposing the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This Amendment purports to grant the Negro the "Political Rights" of "Suffrage" to cast "Votes" within any State and within the United States. It would be most interesting as to what Constitutional authority the Congress of Page 4

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt 1867-68 relied upon to grant the Negro of the southern States the Right to Vote at any election pertaining to the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution? Perhaps the present Congress could enlighten the People of this Nation as to where this authority came from, especially when the Congress of 1869 admitted to the World that the U.S. Constitution needed to be amended before the Negroes could have Civil Rights and/or Rights of Suffrage as evidenced by the existence of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The several State Constitutional Conventions that were organized under the Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867 did not conform to the provisions of the United States Constitution. As evidenced by 15 Stat. 731 Ch. 70; the vote taken to hold a Constitutional Convention within the several southern States were adopted by a large majority. What the Statute did not reveal is that the majority votes of those States were of the COLORED RACE of the population. This fact is confirmed within the May 13, 1868 Senate Executive Document No. 53 of the 40th Congress, 2d Session that was issued in compliance with the Resolution of the Senate of December 5, 1867 by the General of the Army, Ulysses S. Grant. This Document consist of 12 pages and it may be found in the CIS Serial Index of 1867 as S. ex. doc. 53 (40-2) 1317. These Electors and the Members elected to the several State Constitutional Conventions, were made up of the COLORED RACE. They did not have the lawful status of a citizen of a State or of a citizen of the United States nor did they have any Political Rights of Suffrage under any law of any State for want of an Amendment to the United States Constitution. Any Acts of Law coming from those State Conventions or any Legislatures that were convened under the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 are unconstitutional and must be declared so by proper authority. The Unconstitutional State Legislatures The following paragraph, which appears at Section 2 of the Reconstruction Act of July 19, 1867 (15 Stat. 14, Ch. 30), provides us with more Constitutional questions: That the commander of any district named in said act (14 Stat. 428, Ch. 158) shall have power, ... to suspend or remove from office, or from the performance of official duties and the exercise of official powers, any officer or person holding or exercising, or professing to hold or exercise, any civil ... office or duty in such district under any power, election, appointment or authority derived from, or granted by, or claimed under, any so-called State or the government thereof, or any municipal or other division thereof, and upon such suspension or removal such commander. .. shall have power to provide from time to time for the performance of the said duties of such officer or person so suspended or removed, BY THE DETAIL OF SOME COMPETENT OFFICER OR SOLDIER OF THE ARMY, OR BY THE APPOINTMENT OF SOME OTHER PERSON, to perform the same, and to fill vacancies occasioned by death, resignation, OR OTHERWISE. [Emphasis added] Several State Constitutions that were adopted under the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 provided that the members of the Legislatures of those southern States may/shall consist of colored people of whatever race and if the people of those States refused to elect and seat those colored people of whatever race into the Legislatures of their States; the Military Commanders of those Military Districts appointed the members of those Legislatures under the (purported) authority of Section 2 of the Reconstruction Act of July 19, 1867. Whereas the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution WERE NOT IN EXISTENCE at the time the newly elected/appointed Legislators were seated within their respective States and whereas those Legislators consisted of Colored People of Whatever Race; the State Legislatures of the southern States consisted of Members who had no lawful status of being citizens of any State or of the United States. Any Acts (including the Resolutions ratifying the 14th Amendment) that were passed by the newly created State Legislatures are unconstitutional. Said Resolutions of Ratification are without lawful force or effect for they were adopted outside the authority of the Constitution for the United States. Page 5

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt Several Governors of the southern States were removed from Civil Office by Military Commanders under the above cited Section 2 of the Reconstruction Act of July 19, 1867 and were replaced with Army Officials or other military appointees. These Military Commanders or appointees declared that they had the authority to reject or approve Resolutions of the Legislatures of their "Military Districts" and they declared that they had the authority to submit Resolutions of Ratification to the U.S. Secretary of State declaring that the Legislatures of their "Military Districts" had ratified the 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution. [Note: "Military Districts" are not "States" of the Union. "Military Districts" are subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the U.S. Congress while a State of the Union is a foreign corporation to the United States that exercises sovereign authority of its own. The two forms of government are different and they cannot co-exist. The U.S. Congress, in and through its Military Districts, has no authority to ratify Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.]. As these Military Commanders and/or their appointees had no authority under the Constitution of the United States to occupy any Civil Office of a State; the Secretary of State of the United States did not have nor did he ever have any lawful Executive Transmittal of Ratification of the 14th or 15th Amendments within his possession from any southern State. The 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution have never been ratified in accordance to the provisions of the Constitution of the United States and therefore they do not exist. The following paragraph appears at the Preamble of the Reconstruction Acts of March 2, 1861 (14 Stat. 428 Ch. 153) and of July 19, 1861 (15 Stat. 14 Ch. 30): Whereas no legal State government or adequate protection for life or property exists in the rebel States of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Florida, Texas, and Arkansas; ... [Emphasis added] This Preamble openly declares that the Rebel States, named therein, had no lawful State governments and as such, they had no standing as a State of the Union of the united States of America. This paragraph openly admits that Congress had unlawfully rescinded the status of Statehood of those southern States for those States had lawful governments at the time they were admitted into the Union and at the time they ratified the U.S. Constitution, 13th Amendment. The U.S. Congress reduced the southern States to being nothing more than States of the incorporated District of Columbia that are existing as a "Territory" or "Property" of the United States under U.S. Const., IV:3:2. We must ask: "By what authority did the Congress of 1867 rely upon to declare that the southern States had no valid governments and that the civil governments that were in place were operating as 'provisional Governments' subject to the direct authority of Congress when those States were previously brought into the Union of the united States of America on 'equal footing' with the other States?" This is a most interesting constitutional question especially when Congress adopted the following July 24, 1861 Resolution: RESOLVED, That the present deplorable civil war has been forced upon the country by the disunionists of the southern States now in revolt against the constitutional government and in arms around the capital; that in this national emergency Congress, banishing all feeling of mere passion or resentment, will recollect only its duty to the whole country; that this war is not prosecuted upon our part in any spirit of oppression, nor for any purpose of conquest or subjugation, nor purpose of OVERTHROWING or INTERFERING with the RIGHTS or ESTABLISHED INSTITUTIONS of those STATES, but to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution and all laws made in pursuance thereof, and to preserve the Union, with all the dignity, equality, and rights of the several States unimpaired; that as soon as these objects are accomplished the war ought to cease. [Emphasis added] 37th Congress 1st Session. - Mis. Doc. No. 7 Page 6

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt and where the President of the United States had issued the following Proclamations? Insurrection was declared at an end and that peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority now existed in and throughout the whole of the United States Proclamation of the President dated August 20, 1866 The war then existing was not waged on the part of the Government in any spirit of oppression, nor for any purpose of conquest or subjugation, nor purpose of overthrowing or interfering with the rights or established institutions of the States, but to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution and to preserve the Union with all the dignity, equality, and rights of the several States unimpaired, and that as soon as these as those objects should be accomplished this war ought to cease. Proclamation of the President dated September 7, 1867 and when the U.S. Supreme Court declared: When, therefore, Texas became one of the United States, she entered into an indissoluble relation. All the obligations of perpetual union, and all the guarantees of republican government in the Union, attached at once to the State. The act which consummated her admission into the Union was something more than a compact, it was the incorporation of a new member into the political body. And it was final. The union between Texas and the other States was a complete, as perpetual, and as indissoluble as the union between the original States. There was no place for reconsideration, or revocation, except through revolution, or through consent of the States. Considered therefore as transactions under the Constitution, the ordinance of secession, adopted by the convention and ratified by a majority of the citizens of Texas, and all the acts of her legislature intended to give effect to that ordinance, were absolutely null. They were utterly without operation in law. The obligations of the State, as a member of the Union, and of every citizen of the State, as a citizen of the United States, remained perfect and unimpaired. It certainly follows that the State did not cease to be a State, nor her citizens to be citizens of the Union. If this were otherwise, the State must have become foreign, and her citizens foreigners. The war must have ceased to be a war for the suppression of rebellion, and must have become a war for conquest of subjugation. Our conclusion therefore is, that Texas continued to be a State, and a State of the Union, notwithstanding the transactions to which we have referred. And this conclusion, in our judgment, is not in conflict with any act or declaration of any department of the National government, but entirely in accordance with the whole series of such acts and declarations since the first out break of the rebellion. State of Texas, 7 Wall. 700, 19 L.Ed. 227 The question also must be asked: "On what date did the southern States cease to have legitimate governments?" We know that the southern States had legitimate governments at the time they were admitted into the Union of States. We also know that Congress recognized the southern States as having legitimate governments before, during, and after the Civil War (supra.). And we know that the southern States had legitimate governments at the time the Congress submitted the U.S. Constitution, 13th Amendment to the southern States and accepted their ratification votes. Even though the Reconstruction Acts of 1868 does not state the date that the southern States ceased to have legitimate governments, the Reconstruction Acts does state that the southern States had no legitimate governments from the date of the enactment of those Acts of Congress until those southern States were admitted into Congress by an Act of Law [see THIRTY-NINTH CONGRESS, Session II, Chapter 153, Section 6]. By the word of Congress, there were no legitimate ratification votes cast by any southern State Page 7

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt during the years of the Reconstruction Acts of 1866. Further questions must also be asked: "Where does the authority exist that authorizes the Congress of the United States to declare that any 'State' of the 'District of Columbia' ('Territory' of other property of the United States) has authority to 'Ratify' an Amendment to the United States Constitution?" The word: State, as used in the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, can only be given the definition of being a territory or possession that is subject to the jurisdiction of the United States under U.S. Const., IV:3:2: . . . any civil government which may exist therein shall be deemed provisional only, AND IN ALL RESPECTS subject to the PARAMOUNT AUTHORITY OF THE UNITED STATES . ... [Emphasis added] Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867 @ Sec. 6 But the fact that Congress found the need to submit the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the southern States for Ratification and found the need to send its Military into those States to obtain a Ratification Vote to its liking is an admission by the Congress of 1867 that the southern States were States of the Union of the United States of America before, during, and after the Civil War. From the time the President of the United States had declared the Civil War to be at an end by the Proclamations of June 13, 1865 [13 Stat. 763]; of April 2, 1866 [14 Stat. 811]; and of August 20, 1866 [14 Stat. 814] and as those Proclamations were confirmed by Resolutions of the Congress on July 22, 1861 (House Journal, 37th Congress, 1st Session, page 123, etc.) and on July 25, 1961 (Senate Journal, 37th Congress, 1st Session, page 91, etc.); the States of the Union were at Peace with each other and were operating under a Constitutional government. It was those Constitutional governments of the southern States that submitted to the U.S. Secretary of State their Votes of Rejection to the ratification of the 14th Amendment. As those governmental bodies were the only governments of the southern States that were authorized under the Constitution for the United States to execute a Vote the ratification of the 14th Amendment; their votes are the only valid and lawful votes that could have been submitted to the U.S. Secretary of State. THE PRESENT DAY 14th Amendment TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION WAS NEVER RATIFIED FOR IT WAS REJECTED BY MORE THAN ONE FOURTH OF THE STATES THAT WERE IN THE UNION. THE 14th Amendment DOES NOT NOW, NOR HAS IT EVER EXISTED. If the U.S. Congress has the authority to send Military Troops into the freely associated compact States of the united States of America to obtain Votes of Ratification on any Amendment to its liking; then why would there be a need for Constitutional Amendment procedures. For the Legislators of the States to allow the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution to stand Ratified, the Members of those Legislatures would be declaring to the World that they represent a defacto government in which the Congress of the United States has been empowered to exercising absolute dictatorial powers over the People and the States of the united States of America. Proclamation of Ratification In regard to the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment, there appears to be no lawful Proclamation of Ratification on record. The U.S. Secretary of State, William H. Seward, had reservations that the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment had met the qualifications of ratification (see Proclamation of Ratification dated July 20th, 1868) and he expressly stated that he did not issue the Proclamation of Ratification of his free will. (see Proclamation of Ratification dated July 28th 1868). U.S. Secretary of State, William H. Seward, made it clear within the Proclamation of Ratification of July 28th 1868 that he issued the Proclamation under an Order of Congress. (see Concurrent Resolution dated July 21st, 1868). As the U.S. Secretary of State had not issued the Proclamation of Ratification of July 28th 1868 by his independent judgment under the laws of the United States and as the U.S. Congress had not amended the Act of Congress of April 20th, 1818 to grant the Congress Page 8

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt authority to declare the ratification of Constitutional Amendments, there are no lawful publications of Proclamation of Ratification for the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment. The Resolution of Congress ordering the U.S. Secretary of State to issue a Proclamation of Ratification appears to also fail Constitutional legitimacy as it was never submitted to the U.S. President for his approbation as required by Article I, Section 6, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution nor does the U.S. Constitution authorize the U.S. Congress to execute the laws of the United States. Political Question For several years, the Federal Judiciary took jurisdiction and made ratification rulings of Constitutional Amendments. Almost all of those cases were dismissed on the merits of the case. Even with the 1939 U.S. Supreme Court case of Coleman vs. Miller (307 U.S. 433), the Federal Courts took jurisdiction after a Constitutional Amendment was proclaimed to have been ratified; that was until the question of ratification of the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment was brought before the Federal Courts. The U.S. Supreme Court case of Coleman vs. Miller declares that from the time Congress adopts a Joint Resolution to propose an Amendment to the U.S. Constitution until the time the States have ratified the Amendment, the question of ratification of Amendments were Political Questions to the Courts. With the Federal Court cases of Epperly vs. United States (U.S. District Court No. J90-010-CV; Federal Court of Appeals No. 91-35862; U.S. Supreme Court No. 93-170) challenging the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment, the Federal Courts enlarged the case of Coleman vs. Miller to include Amendments that have been purportedly ratified by Proclamation of Ratifications. With the Federal Courts declaring that an Amendment to the U.S. Constitution will no longer be determined by the Courts to have been adopted in accordance to the U.S. Constitution as required by the Act of Congress of April 20th, 1818 and by 1 USC 106b, the people of the United States of America are now left without recourse. EVERY BRANCH OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT HAVE GONE ON RECORD DECLARING THAT THEY HAVE NO JURISDICTIONAL AUTHORITY TO INVESTIGATE OR MAKE JUDGMENTS INTO THE QUESTION OF THE RATIFICATION OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION, 14th Amendment. What few Federal Courts that addressed the ratification question went on record stating that as the Federal Judiciary and the U.S. Congress have used the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment for so many years, the use of the (pretended) Amendment validates the Amendment as being legitimate (an absurdity in law). Constitutional Construction The rules of Constitutional construction are well known and were approved by the framers of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867-68. On January 25, 1872, a unanimous Senate Judiciary Committee Report, signed by the Senators who had voted for the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments in Congress declared: In construing the Constitution we are compelled to give it such interpretation as will secure the result which was intended to be accomplished by those who framed it and the people who adopted it. The Constitution, like a contract between private parties, must be read in the light of the circumstances which surrounded those who made it ... . If such a power did not then exist under the Constitution of the United States, it does not exist under this provision of the Constitution, which has not been amended. A construction which should give the phrase 'a republican form of government' a meaning differing from the sense in which it was understood and employed by the people when they adopted the Constitution, would be as unconstitutional as a departure from the plain and express language of the Constitution in any other particular. This is the rule of interpretation adopted by all commentators on the Constitution, and in all judicial expositions of that instrument; and your committee are satisfied of the entire soundness of this principle. A change in the popular use of any word employed in the Constitution Page 9

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt cannot retroact upon the Constitution, either to enlarge or limit its provisions. Accordingly, in order to determine whether recent construction of the Reconstruction Acts are correct, it is necessary to read the debates in Congress when these Amendments were being proposed. Unfortunately, these debates are often inaccessible. First, the CONGRESSIONAL GLOBE and RECORDS in which these debates are found are now a century old. Few libraries have them, and the available sets will be progressively reduced by wear and tear which inevitably comes with age. Microfilm copies cannot be read by more than one person at a time. Secondly, relevant debate is scattered through a large amount of irrelevant material. Discussions pertinent to the Reconstruction Acts are found from 1849 to 1875. But during this era, Congress discussed many other unrelated pieces of legislation. Even when these Amendments were directly under consideration, many irrelevant remarks of a political or personal nature were made by members of Congress. The GLOBE index is not always a certain guide, since discussions pertinent to the Amendments are found in debates on other topics, while members of Congress often digressed in their remarks on the Amendments themselves. Thus, persons interested in analyzing the legislative history of the Reconstruction Acts are forced to wade through an enormous quantity of extraneous matter in order to cull out the pieces of pertinent debate. The task is formidable. Analysis of Committee Reports requires equally tedious labor. We are grateful to the People of the State of Virginia that spent the time, expense, and research that must have taken to reproduce the Congressional debates on the Reconstruction Acts. The Congress, Session, Dates, and Pages of the GLOBE, RECORD, or Committee Reports from which the material is taken from are found on each page of the THE RECONSTRUCTION AMENDMENTS DEBATES as published by the Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government in 1967. The speaker is identified at the beginning of each speech, or part that has been reproduced in the Documents. No comment or other textual material has been added to the debates themselves as it was felt that the Documents should only reproduce the relevant parts of the original debates. The State of Virginia record of the Congressional debates on the Reconstruction Acts and the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment may be located in a Depository Library of your State or a bookstore on the Internet. The U.S. Supreme Court Over the last 50 years, or so, the U.S. Supreme Court has discovered numerous surprising new principles in our 200-year-old Constitution. In almost every case, the amazing new principle was said to reside in the 135 year-old 14th Amendment, possibly in combination with some other Amendment. Let's review a few examples. The Supreme Court has told us that the 14th Amendment, in combination with the First Article of the Bill of Rights, protects flag burning. Yet our forefathers, who adopted the 14th Amendment, punished public desecration of the American flag with death. The Court has told us that the 14th Amendment demands gender equity in all State and local programs. But Section 2 of the 14th Amendment expressly permits, even encourages, gender discrimination by the States in federal elections. The U.S. Supreme Court claimed that the 14th Amendment mandates forced busing to integrate public schools. That would be a big surprise to the Congressmen who framed the Amendment in 1866. They intended quite the opposite and they said so on the record. Even liberal law professors admit this fact. See, for example, the Essay by Laurence Tribe in Scalia. [See page 68 of the Essay by Tribe in A Matter of Interpretation, by Antonin Scalia]. The Thirty-Ninth Congress, which drafted the 14th Amendment, also passed legislation which retained racial segregation in the Washington, D.C. Schools. When the Senate voted to adopt the 14th Amendment, it had separate black and white sections in its visitors' gallery. [An account of the 14th Amendment's history relative to school segregation can be found in Berger, 1977, Chapters 4 and 7]. Page 10

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt The U.S. Supreme Court claims that the 14th Amendment forbids any meaningful State restrictions on abortion. Yet, when the States ratified the Amendment, most of them had anti-abortion laws on the books. They passed or toughened many of those laws in 1860's and 1870's, right around the same time when the 14th Amendment was [purportedly] ratified. Congress passed laws in 1865 and 1872 making it a criminal offense to send abortion information through the mail. So we are told that, at the time Congress and the States were passing laws against abortion, they amended the Constitution to nullify all those laws. [See Mohr, 1978, pages 195-225 to review the history of mid 19th Century abortion laws. ]. Contemporaneous with the adoption of the 14th Amendment, Congress passed four enforcement laws, (in 1866, 1870, 1871, and 1875) as Section 5 of the Amendment expressly authorized. The text of those four laws, which ran in total to over 8000 words, was completely devoid of any language to support claims that the 14th Amendment protected flag burning or abortion, or demanded public school integration or gender equity in State programs. Given the numerous and obvious contradictions between the historical record and the claims of our judicial employees, one is entitled to wonder: Are the U.S. Supreme Court Justices making stuff up out of whole cloth? Do We the People have a major problem with employee fraud? Perish the thought, say liberal elites who would like us to believe that the U.S. Constitution protects flag burning, abortion, and all that other stuff. They offer two main cover stories to explain away the contradictions. The first one goes something like this. Yes indeed, no one back then intended the 14th Amendment to protect flag burning or abortion. No one intended it to demand gender equity or public school integration. But the framers were very wise. They knew that we would need changes as time went on. So they used sweeping, vague language, guaranteeing things like due process. They wanted to give the Supreme Court the tools it needed to adapt the Constitution to the needs of changing times. Let's call this one the vague-on-purpose story. The other main cover story goes more or less as follows. Prior to the ratification of the 14th Amendment, the Bill of Rights restricted only the federal government. But the framers of the 14th Amendment decided to change that. They wrote the Amendment to incorporate the Bill of Rights against the States, so that Federal Courts would be able to force the States to honor our basic civil rights. Let's call this one the incorporation cover story. The U.S. Supreme Court prefers a combination of the two cover stories. The Court has long taken the position that our forefathers intended the due process clause of the 14th Amendment to incorporate parts of the Bill of Rights against the States. Exactly which parts it incorporates changes from time to time. Whenever these changes occur, the Court will let us know. The authors of the Amendment also intended to give the Court free rein to expand, without limit, the meaning of the term due process. A review of the history of the 14th Amendment reveals that both cover stories are false. We'll take them one at a time. THE VAGUE-ON-PURPOSE COVER STORY There are at least four reasons to reject the vague on purpose cover story. The first reason involves the 14th Amendment itself. Its Section 5 explicitly assigns Page 11

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt enforcement power to Congress, not the Courts. Congress included Section 5 in response to a catastrophic piece of recent U.S. Supreme Court mischief. In 1857, the Court had handed down the Dred Scott decision, a decision that was motivated by judicial bias and was grossly unjust, a decision that Abe Lincoln called a perversion of the Constitution, and a decision that Lincoln's contemporaries blamed for causing the Civil War. [Lincoln is quoted by Senator Jenner during the August 20, 1958 debates on the Jenner-Butler Bill. See the 1958 Congressional Record -Senate, page 18645] After the Civil War ended, Congress responded to the Court's brazen power grab; it proposed the 14th Amendment. The Amendment's first Section nullified the Dred Scott decision; its last paragraph said, Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. That language wasn't used in Constitutional Amendments until after the Civil War. Congress then began including such language to limit the Court's ability to pervert the Constitution. The Court actually admitted that Section 5 was intended to reserve enforcement power to Congress for a decade or so after the 14th Amendment was passed. In 1879, in Ex Parte Virginia, the Supreme Court wrote: It is not said (by the 14th Amendment, that) the judicial power of the general government shall . . . be authorized to declare void any action of a State in violation of (its) prohibitions. It is the power of Congress which has been enlarged. Congress is authorized to enforce the prohibitions by appropriate legislation. [Professor doubt that power from page 221. web site.] Raoul Berger's "Historical Review" (see his Chapter 12) showed beyond the framers intended the language in Section 5 to withhold enforcement the Courts. [The quote from Ex Parte Virginia can be found in Berger on You can read the whole decision at the 'Lectric Law Library Lawcopedia's

The second reason is simple and obvious. The framers of the 14th Amendment obviously knew the proper way to adapt the Constitution to meet the needs of changing times. They did it three times within the space of five years, adopting the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, the Fourteenth in 1868, and the Fifteenth in 1870. They used the method that the Constitution expressly provides us for that purpose. The third reason involves the legislation that Congress passed to enforce the 14th Amendment. That legislation (which ran in aggregate to 8,149 words) was quite specific and detailed. Over the years, the U.S. Supreme Court found pretexts to nullify most of it because the Justices found it distasteful. Nevertheless, it is beyond dispute that the enforcement legislation expressed the intent of our founders in framing and ratifying the 14th Amendment. The Congresses that passed the enforcement legislation were contemporaneous with and dominated by the same political party as the Congress that framed the 14th Amendment and most of the State legislatures that ratified it. [In nullifying the 14th Amendment enforcement legislation, our judicial employees caused African American citizens to suffer almost a century of Ku Klux Klan terrorism and Jim Crow laws in parts of the South. The fourth reason is the clincher. At the time the 14th Amendment was drafted and ratified, distrust for the Supreme Court was at an all-time high. According to a Lincoln biographer, the Republicans (who sponsored the 14th Amendment) viewed Chief Justice Taney's death in 1864 as the removal of a barrier to human progress. In May, 1861, the New York Tribune had written that Chief Justice Taney takes sides with traitors . . . throwing about them the sheltering protection of the ermine. That same year, the New York Times observed that Chief Justice Taney would go through history as the judge who dragged his official robes in the pollutions of treason. The Chicago Tribune called the Supreme Court the last entrenchment behind which Despotism is sheltered. [See Silver, pages 223, 231, 232, and 239]. Page 12

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt In December, 1866, The Washington Chronicle wrote that treason had found a refuge in the bosom of the Supreme Court of the United States. In March, 1867, Harper's Weekly accused the Court of trying to reverse the results of the war. In April, 1867, the National Independent wrote that the Supreme Court was regarded as a diseased member of the body politic, and was at risk of amputation. Much of this criticism of the Court occurred while the 14th Amendment was before the States for ratification. [See Warren, Volume III, pages 170, 174, and 181. The 14th Amendment was adopted by Congress on June 13, 1866 and [purportedly] ratified by a sufficient number of States on July 9, 1868]. Members of Congress, who framed the 14th Amendment, were also disgusted with the Court. They believed that it was usurping political power and that one of its usurpations had caused the Civil War. In January, 1864, Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire made the following statement on the floor of the Senate: I will take this occasion to say that in my humble judgment if there was a single, palpable, obvious duty that the Republican party owed to themselves, owed to the country, owed to humanity, owed to God when they came into power, it was to drive a plowshare from turret to foundation stone of the Supreme Court . . . [The quote attributed to Senator Hale can be found in Silver, page 139. The quote attributed to Congressman Stevens can be found in a footnote on page 222 of Berger, 1977. The description of John A. Bingham as the leading House moderate was on page 86 of Maltz. The Bingham quote was taken from Warren, Volume III, pages 170-171. Most of the quote also appears in Boudin, Vol. II, page 75]. In 1865, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania expressed the opinion that recently deceased Chief Justice Taney was damned . . . to everlasting fire. Listen to excerpts from a speech given in the House of Representatives by John A. Bingham, of Ohio. Bingham has been described by historians as the leading House moderate on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction (which drafted the 14th Amendment). In January 1867, Bingham proposed sweeping away at once the court's appellate jurisdiction in all cases. He went on to say: If, however, the court usurps power to decide political questions and defy a free people's will, it will only remain for a people thus insulted and defied to demonstrate that the servant is not above his lord, by procuring a further Constitutional Amendment and ratifying the same, which will defy judicial usurpation, by annihilating the usurper's (Amendment) in the abolition of the tribunal itself. That's pretty strong language for the leading House moderate among the 14th Amendment's framers. It underscores the degree of mistrust of the Supreme Court held by those framers. In March 1868, for the only time in American history, Congress passed a law (The Judiciary Act of 1868) which diminished the scope of the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction. A little later, in Ex Parte McCardle, the Court unanimously upheld the law. The justices swallowed this bitter pill because the law had passed in the Senate by a vote of 33-9 and in the House by 115-57. Its sponsors probably had the votes to impeach and remove as many Supreme Court Justices as they thought necessary. [See Murphy, Walter F., page 27. See also Warren, Vol. III, pages 195-210]. This is obviously not the sort of climate in which Congress would adopt an Amendment to give the Court a blank check to revise the Constitution to meet the needs of changing times. In the 1860's, Congress viewed an out-of-control Judiciary as the problem, not the solution. THE INCORPORATION COVER STORY If the 14th Amendment empowered Federal Courts to enforce the Bill of Rights against the States, this was one of the best kept secrets in American history. There was no Page 13

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt clue to this intent in the four enforcement Acts that Congress passed contemporaneous with the Amendment. Furthermore, the Supreme Court itself was totally unaware of this sweeping new power a scant nine months after the Amendment was ratified. We select from a multitude of cases those which we deem to be leading: Barron v. Baltimore, 7 Pet. 243; Fox v. Ohio, 5 How. 410, 434; Twitchell v. Commonwealth, 7 Wall. 321; Brown v. New Jersey, 175 U.S. 172, 174; Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U.S. 78, 93. In the case of Twitchell v. Commonwealth (supra.), Mr. Twitchell had been convicted of murder under a process which his lawyer claimed violated the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. The Supreme Court (unanimously) disposed of the case by citing the original understanding that the Bill of Rights restricted only the federal government, not the States. Nobody mentioned the 14th Amendment in that case. If the 14th Amendment was intended to incorporate the Bill of Rights against the States, you would think that nine months after it was ratified somebody would have known about this intent, either the Plaintiff's lawyer, or one of the nine eminent Constitutional Lawyers on the 1869 Supreme Court. [See Fairman, "History of the Supreme Court of the United States," Vol. VI, Part I; "Reconstruction and Reunion" at pages 212, 213]. A law professor (named Stanley Morrison) reviewed a dozen different cases between 1868 and 1947 in which various defense lawyers asserted that the Bill of Rights should restrict the States as well as the federal government. In the first few cases, the 14th Amendment wasn't even mentioned. It wasn't until 1887, nineteen years after the Amendment was added to the Constitution, that a resourceful lawyer decided to try the incorporation story line. [See Morrison, "The Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights;" "The Incorporation Theory" at pages 229, 230]. The Court rejected this argument unanimously until 1892, twenty-four years after the Amendment was debated, passed, and ratified. At that point, a few dissenters began to sign on to the fraud. A few years later, the Court decided to incorporate the takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment in order to develop a scam for use in protecting corporations from regulation by the States. [ See, for example, Levy (1986) page 167. See also the Essay by Professor Lino Graglia (pages 86-101) in Licht et. al. ]. In 1876, Congress debated, and almost passed, a Resolution to recommend to the States a proposed Constitutional Amendment to impose the First Amendment's religious freedom mandates on the States as well as the federal government. The so called Blaine Amendment said: No State shall make any laws respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; and no money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefore, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised or lands so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations. Many of the folks who voted to adopt or ratify the 14th Amendment were (still) in Congress when it debated the Blaine Amendment. They surely remembered what they had done, and intended, a scant eight years earlier. They would not have bothered with a new Amendment to redo what they had already accomplished with the 14th Amendment. Charles Fairman, a colleague of Professor Morrison, performed an exhaustive review of historical material which might illuminate the intent of the framers of the 14th Amendment with respect to the incorporation claim. He studied the debates in Congress, speeches by Congressmen campaigning for reelection in 1866, proceedings in the various State legislatures which ratified the Amendment, and relevant articles in the major newspapers of the time. Then he wrote a lengthy article reporting what he found. [Fairman's Article is on pages 85-219 of Fairman and Morison's The Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights: The Incorporation Theory. A political scientist named Horace E. Flack published a book in 1908 (Republished by Peter Page 14

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt Smith, Gloucester, Mass., 1965) in which he presented all the evidence he could find to support the incorporation theory. The evidence was a bit scanty. And the few scraps there were only supported the claim that Congress intended Section 5 to empower itself to bring the States under the Bill of Rights, using the privileges and immunities language, should it choose to do so. Horace E. Flack found no evidence whatever which indicated that Congress intended the 14th Amendment's due process clause to empower the Supreme Court to usurp power to decide political questions.]. In summarizing, Professor Fairman wrote that he found a mountain of evidence debunking the incorporation story line and only a few stones and pebbles to support it. That probably explains why it took the Supreme Court a generation to learn about the story. SEPARATION OF CHURCH AND STATE In recent years, the U.S. Supreme Court has claimed authority to interpret the U.S. Constitution and declare that the First Article of the Bill of Rights no longer is limited to the establishment of a State created Church such as the Church of England, but is now defined to be a Doctrine of Separation of Church and State and has the authority to apply that Doctrine upon the States of the Union through the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment. If this authority exist, then there are a few questions to be asked: (1) If the Federal Courts have the authority to interpret the Federal Constitution in declaring that the First Amendment's original purpose and intent was not to create a National Church, such as the Church of England, but to establish a Doctrine that there was to be a Separation of Church and State and then applying that Doctrine to the States under the purported authority of the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment, why then is that Doctrine being applied only to the Christian faith? (2) Why is the Doctrine of Separation of Church and State never applied to the State and Federal Governments? Does not the Federal Government enter into "Treaties" with the Catholic Church? Does not the State Governments create "Church Corporations" to which every Church Denomination has been incorporated thereunder? And does not the State and Federal Governments regulate the "Church" through their Revenue and Tax Codes under their purported corporate authority? [see exemption from federal income tax under Section 501(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 by being listed as an exempt organization under Section 501(c) of the Code (26 U.S.C. Section 501 (c))]. (3) In regard to the recent rulings of the Federal Courts removing "Symbols" of Christian faith from Public Schools and other Public Facilities (such as State and Federal Courtrooms and Government Memorials), are not these "Symbols" the symbols of government created corporations known as "Church Corporations?" If this is so, must we ask by what authority do the Federal Courts rely upon to apply the Doctrine of separation of Church and State to such Symbols when those Symbols represent the government? (4) With the recent ruling of the U.S. Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, mandating that the City of San Diego must remove a Christian Cross from a War Memorial, will not the Federal Courts go so far as to mandate that all references of "God" and Christian Crosses be removed from all City, County, and the Arlington National Memorial grave sites? (5) If there is a Doctrine of Separation of Church and State as declared by the United States Supreme Court, how come the States and the Federal Government will not recognize the Churches as having sovereign powers and immunities to govern themselves as a sovereign Nation? (6) If there is a Doctrine of Separation of Church and State, we must ask as to what authority the Congress or the President is relying upon to enter into a "faith base" relationship with Church denominations? Page 15

U.S. Constitution Amendment.txt Conclusion The U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment is being applied by the U.S. Congress and the Federal Courts as a tool of war upon the States and their citizens. Even the Negro population has been made a victim of the 14th Amendment in that they were forcefully taken from their homeland and made citizens of the United States by birth and not the choice of free will. The authors of the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment had calculating motives in that the underlying purpose of the Amendment was to transfer the reserved Powers of the States and the People to the Federal Government. It allowed the Federal Government to create "Corporations" for the purpose of distributing fiat paper money in "discharge" of debts instead of providing lawful currency in the form of silver and gold coins in "payment" of debts (see "Payment" vs. "Discharge" in the case of Stanek v. White, 172 Minn. 390, 215 H.W. 784). In other words, the U.S. Congress granted an elite group of people the "Title of Nobility" to control the money supply of our country, the United States of America, and thus they control the politics and policies of our government. I am not here to pass judgment on the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment, but if it is the will of the people to turn the Constitution of the United States upon its head via an Amendment, so be it! But only if it is done in a lawful manner. The U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment was not ratified in accordance to the provisions of the Constitution for the United States of America and as such, it does not exist. It survives as a matter of fraud and deception. I have done my best to have the question of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment answered by the Judges of our Federal Courts or by Members of the U.S. Congress, but to no avail. On this web site, you will see my collection of Court Cases, Letters, Articles, and other Documents that show the U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment has no lawful existence. What has to be done next will be a question you will have to decide. I would like to thank D.J. Connolly for his contribution to this "Introduction." Gordon Epperly

Page 16

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pope Francis General Civil Orders LetterDocument7 pagesPope Francis General Civil Orders LetterAriel El85% (26)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Mercola: How To Legally Get A Vaccine ExemptionDocument7 pagesMercola: How To Legally Get A Vaccine ExemptionJonathan Robert Kraus (OutofMudProductions)100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Few Cases On FraudDocument3 pagesA Few Cases On Frauddbush2778100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Admin Law ReviewerDocument3 pagesAdmin Law ReviewertynajoydelossantosNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Essay OneDocument8 pagesConstitutional Law Essay OneshizukababyNo ratings yet

- Fee Jee PMFM47Document7 pagesFee Jee PMFM47Jim100% (3)

- Ateneo Utopia Constitutional Law Reviewer 2011 Part I Version 4Document139 pagesAteneo Utopia Constitutional Law Reviewer 2011 Part I Version 4Julxie100% (3)

- Equal Protection ClauseDocument29 pagesEqual Protection ClauseSuiNo ratings yet

- Senior Citizen Act AmendedDocument30 pagesSenior Citizen Act AmendedMaica ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Applegate - Scouting and PatrollingDocument127 pagesApplegate - Scouting and Patrollingbishskier100% (2)

- Easy To Build Hydroponic Drip SystemDocument12 pagesEasy To Build Hydroponic Drip Systemahalim4uNo ratings yet

- 012 Flast V Cohen 392 US 83Document2 pages012 Flast V Cohen 392 US 83keith105No ratings yet

- Case Digest - ConstiDocument5 pagesCase Digest - ConstiGlenice Joy D JornalesNo ratings yet

- Saguisag V Ochoa DigestDocument2 pagesSaguisag V Ochoa DigestJustin ParasNo ratings yet

- TAX 1 CASE DOCTRINESDocument30 pagesTAX 1 CASE DOCTRINESAnony mousNo ratings yet

- Data ModemsDocument137 pagesData ModemsmdaveryNo ratings yet

- Coil WinderDocument2 pagesCoil WindermdaveryNo ratings yet

- Smart (R) Electronic Watt-Hour MetersDocument12 pagesSmart (R) Electronic Watt-Hour MetersmdaveryNo ratings yet

- Inverter Transformer Core GesignDocument18 pagesInverter Transformer Core GesignThameemul BuhariNo ratings yet

- Slaa577g PDFDocument43 pagesSlaa577g PDFmdaveryNo ratings yet

- Forcast WeatherDocument1 pageForcast WeathermdaveryNo ratings yet

- An Example of The RSA AlgorithmDocument4 pagesAn Example of The RSA AlgorithmstephenrajNo ratings yet

- 1 StquotesDocument67 pages1 StquotesmdaveryNo ratings yet

- Beowulf (700-1100)Document214 pagesBeowulf (700-1100)GroveboyNo ratings yet

- 13 30139Document5 pages13 30139mdaveryNo ratings yet

- Color Washer ManualDocument44 pagesColor Washer ManualmdaveryNo ratings yet

- Legal RemediesDocument345 pagesLegal RemediesmdaveryNo ratings yet

- On TargetDocument41 pagesOn TargetmdaveryNo ratings yet

- Basket Making WorkshopDocument0 pagesBasket Making WorkshopmdaveryNo ratings yet

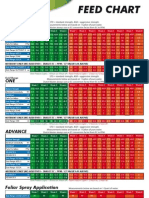

- Dutch Master Grow Chart GuideDocument10 pagesDutch Master Grow Chart GuidemdaveryNo ratings yet

- Book The Pyramid Lesbrown 38pages 8mbDocument38 pagesBook The Pyramid Lesbrown 38pages 8mbmdaveryNo ratings yet

- MIlitary High ExplosivesDocument7 pagesMIlitary High ExplosivesChristiaan WilbersNo ratings yet

- SB 5100Document34 pagesSB 5100cab13guyNo ratings yet

- E4200 Gateway MaintenanceDocument108 pagesE4200 Gateway MaintenancemdaveryNo ratings yet

- Motorola Modem SB5120Document74 pagesMotorola Modem SB5120Berks Homes100% (1)

- GATT Dispute Resolution from a Developing Country's PerspectiveDocument188 pagesGATT Dispute Resolution from a Developing Country's PerspectivedecemberssyNo ratings yet

- Social Studies 5th 2017Document21 pagesSocial Studies 5th 2017api-267803318No ratings yet

- Hussainara Khatoon & Ors Vs Home Secretary, State of Bihar, ... On 9 March, 1979Document9 pagesHussainara Khatoon & Ors Vs Home Secretary, State of Bihar, ... On 9 March, 1979Sumit SahooNo ratings yet

- Simonelli Plaintiff v. City of Carmel Defendant COMPLAINT CASE No. 3 13 CV 1250 LB Filed 03-20-13Document13 pagesSimonelli Plaintiff v. City of Carmel Defendant COMPLAINT CASE No. 3 13 CV 1250 LB Filed 03-20-13L. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- July 14, 2016 Case DigestDocument15 pagesJuly 14, 2016 Case DigestGrace CastilloNo ratings yet

- Proano IndictmentDocument2 pagesProano IndictmentColin DailedaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Case Challenging Army Prosecution for Civilian DeathDocument34 pagesSupreme Court Case Challenging Army Prosecution for Civilian DeathShreyaNo ratings yet

- Political Law Part V Legislative PowerDocument18 pagesPolitical Law Part V Legislative PowerHana Danische ElliotNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Respondents Arthur D. Lim The Solicitor GeneralDocument57 pagesPetitioner Vs Respondents Arthur D. Lim The Solicitor GeneralTori PeigeNo ratings yet

- AP Gov TestDocument23 pagesAP Gov TestRunner128No ratings yet

- Chandler v. Florida, 449 U.S. 560 (1981)Document24 pagesChandler v. Florida, 449 U.S. 560 (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Peace 101Document66 pagesPeace 101Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process100% (1)

- La Bugal-B'Laan Tribal Association, Inc. vs. RamosDocument12 pagesLa Bugal-B'Laan Tribal Association, Inc. vs. RamosylessinNo ratings yet

- PhilThread vs. Confesor - Labor RelationsDocument3 pagesPhilThread vs. Confesor - Labor RelationsSyoi DiazxNo ratings yet

- Civil War Causes H DBQ WalshDocument24 pagesCivil War Causes H DBQ Walshapi-281321560No ratings yet

- Criminal Law NotesDocument6 pagesCriminal Law NotesRyan ChristianNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law - Due Process - Double TaxationDocument3 pagesConstitutional Law - Due Process - Double TaxationWilly WonkaNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna As Represented by Rep Satur Ocampo Et Al Vs Alberto Romulo in His Capacity As Executive Secretary Et AlDocument58 pagesBayan Muna As Represented by Rep Satur Ocampo Et Al Vs Alberto Romulo in His Capacity As Executive Secretary Et AlShannin MaeNo ratings yet