Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Australian Takeovers AJM 1984

Uploaded by

pnrahman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views57 pagesJournal Article

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentJournal Article

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views57 pagesAustralian Takeovers AJM 1984

Uploaded by

pnrahmanJournal Article

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 57

http://aum.sagepub.

com/

Australian Journal of Management

http://aum.sagepub.com/content/9/1/63

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/031289628400900105

1984 9: 63 Australian Journal of Management

Terry S. Walter

Australian Takeovers: Capital Market Efficiency and Shareholder Risk and Return

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Australian School of Business

can be found at: Australian Journal of Management Additional services and information for

http://aum.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://aum.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://aum.sagepub.com/content/9/1/63.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Jun 1, 1984 Version of Record >>

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

AUSTRALIAN TAKEOVERS:

CAPITAL MARKET EFFICIENCY

AND SHAREHOLDER RISK AND RETURN

by

Terry S. Walter*

Abstrract:

This paper' e:r:plains the shar'e rrnr'ket.'s r'esponse to Austrral,ian takeover' bids.

Both successful, and unsuccessful bids ar'e consider'ed. TWo issues ar'e addr'essed.

Fir'stl,y, takeover's ar'e viewed in of c01'porrate investment decisions; the

pr'ofitabil,ity of these decisions to the offer'ee and to the offe1'or' ar'e

investigated. Secondl,y, takeover' bids ar'e seen as a valuabl,e sour'ce of

info'Y'l'l'rZtion r'el,evant to the deteromination of a fi1'm.'s shar'e rrnr'ket

capital,isation. The adjustment of sha1'e pr'ices to this info'Y'l'l'rZtion sour'ce is

studied within the context of the Efficient Mar'kets Hypothesis. The r'esul,ts

indicate that offer'ee shar'ehol,der' r'etu1'nS ar'e no'Y'l'l'rZl, Or' bel,ow no'Y'l'l'rZl, proior' to a

bid; wher'eas offer'or's exhibit above averrage r'etu1'ns. When a bid is rrnde, offer'ee

shar'ehol,der's typical,ly r'eceive significant positive excess r'eturons; wher'eas

offer'or' shar'ehol,der's gain no additional benefit. Austrral,ian shar'e rrnr'kets ar'e

to be semi-str'ong efficient in the Farna sense, namel,y that info'Y'l'l'rZtion

rrnde publ,ic duroing takeover' negotiations is rrapidl,y and without bias inco1'porrated

into shar'e proices.

Keywo1'ds:

TAKEOVERS; EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS; RISK; SHAREHOLDER RETURN;

ASSET PRICING; MERGERS

*Department of Accounting, University of New South Wales. This paper is drawn

from my Ph.D. thesis at the University of Western Australia. The study was

inspired by Professor Philip Brown whose comments and encouragement are

gratefully acknowledged. The comments of participants at workshops at the

Australian Graduate School of Management, the University of Queensland and

the University of Western Australia and those of examiners and a reviewer are

also acknowledged, in particular R. Ball, P. Dodd, G. Foster, F. Finn and

R. Officer. The usual exclusions apply.

63

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

This paper explains the share market response to Australian takeover

announcements. Two issues are addressed. Firstly takeovers are discussed in

terms of corporate investment decisions. The profitability of these decisions to

the of feror and to the of feree are invest igated. Secondly takeover bids are

viewed as the public release of information potentially relevant to the

determination of a firm's share market capitalisation. The adjustment of share

prices to the announcement of takeover bids is studied.

The study has its justification in the following grounds.

i. Takeovers are frequent events in Australia.

Several authors have documented incidence and outcome statistics for

Australian takeover bids. Bushnell (1961) studied bids during 1945 to 1959,

and both Walker (1973) and Stewart (1977) investigated takeover activity

during 1960 to 1970. Walker, for example, estimated that 38 percent of

firms which were listed on the Sydney stock exchange at some stage during

1960 to 1970 were subject to a bid, and that four out of five bids

succeeded.

ii. Takeovers are significant events.

Receipt of a takeover bid is among the most significant shocks in a firm's

history. For the offeree, a successful bid often leads to the end of

shareholder independence, and frequently results in major managerial and

policy changes. For the offeror, takeovers can involve significant

investment outlays, together with considerable changes to the firm's

financial structure, asset base and related earnings stream.

iii. Australian evidence on takeovers is incomplete.

There has been only one major study [Dodd (1976) 1 directed specifically at

describing the share market returns associated with takeovers. This is

surprising given the frequency of takeover bids. However, Dodd's results

are in part inconsistent with recent overseas eVidence, and with the

hypotheses he tested.

l

1. TAKEOVERS AND SHAREHOLDER RETURNS

Takeovers are a controversial issue in the finance literature.

Viewpoints exist at the theoretical and motivational levels.

2

Extreme

Takeovers have, for example, been advanced as a vehicle used by business to

exploit market imperfections.

3

It is argued that certain firms can actively seek,

discover and acquire firms whose resources are undervalued in the share market.

Under this scenario it is expected that shareholders of firms involved in market

exploitation earn excess positive returns.

4

It is often suggested that regulation

post-bid excess negative returns of approximately seven percent

per year for shareholders of firms whose bids were successful. This result is

anomalous with respect to market efficiency.

2. Steiner (1975) provides an excellent coverage of much of the recent

theoretical literature on the causes of takeovers.

3. See, Lintner (1971) for an attempt to develop such a theory of mergers.

4. An excess positive (negative) return in this paper is defined as a return that

is greater (less) than that expected for a given level of risk. An excess

64

COPYright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

or reform is required to protect the interests of shareholders whose ownership

claims are acquired.

5

In contrast, it has been argued that managerial self-interest is the primary

motivation in takeovers;6 that management engages in takeovers to maximise firm

size rather than shareholder wealth. Acquiring firms are supposed to earn excess

negative returns. It is argued that management retains its position due to

separation of ownership and control. Managerial behaviour as hypothesised in the

development of the 'traditional' self-interest motive can occur only when

breakdowns exist in the market for corporate control or the managerial labour

market. Clearly, separation of the managerial decision-making-function and the

risk-taking function can and does eKist without managers pursuing non-value

maximising behaviour.

7

Between these extremes lies the notion of an acquisitions market, or market for

corporate control, where competition among bidding firms works to ensure that

"bargains" ex ante do not exist. Prices paid in takeovers are such that the

expected return from an acquisition is commensurate with the level of risk

inherent in the investment.

8

This represents a special, and perhaps unrealistic,

case of a competitive acquisitions market hypothesis. Suppose synergistic

benefits from an acquisition are specific to a particular offeror. Here the

successful offeror, facing a competitive market for acquisitions, will pay at

least the value of the target to any alternative bidder. Hence the existence of

a competitive market does not necessarily imply normal returns for an offeror.

Clearly some offerors do earn abnormal returns in acquisitions.

(IE) Hypothesis

Dodd and Ruback (1977, p.354) argue:

"the hypothesis contends that the assets of the target firm were not being

utilised efficiently prior to the takeover offer. The bidding firm is

assumed to be motivated by information on the inefficiency Whatever the

origins of the inefficiency, the announcement of a takeover is received as

positive information for the target firm, irrespective of the outcome of

the offer".

Mergers may thus be viewed as a capital market mechanism to remove resources from

the monopolistic control of firm managers who are under-utilising them to

competing firms which can use them more effectively. Irrespective of the origins

of the existing under-utilisation, the unanticipated announcement of a takeover

positive (negative) return is also referred to in this paper as a gain (loss).

Several alternative terms are found in the finance literature to describe returns

greater (less) than those expected for a given level of risk. These include

abnormal return, abnormal performance and above-average returns. See, Fama

(1970, 1976), or Foster (1978).

5. Chambers (1973) strongly advocates the case for the reform of the "quality" of

accounting informati.on.

6. See, Mueller (1969), but see also, Grabowski and Mueller (1975).

7. See, Fama (1980).

8. See, Mande1ker (1973).

65

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

bid usually increases the market capitalisation of the offeree because it

increases the expected value of shareholder future wealth. Four out of five bids

are successful and for the one that is not, unless permanent barriers

9

to an

offeree's acquisition are erected in response to the bid, its market

capitalisation should also increase. The reason is that the probability of

receiving a second (successful) bid at a future date conditional on an

unsuccessful bid now, exceeds the unconditional probability.lO

The implications of the internal efficiency hypothesis for offeror returns are

less clear, and depend on the market's evaluation of the offer price and new

information released in the bid. Dodd and Ruback explain (1977, p.354):

"if information of the target firm's inefficiency is publicly available

prior to the offer, competition in the acquisitions market would imply

normal returns for the bidding firms. If the information is not publicly

available prior to the offer and is not released during the offer, positive

abnormal returns will be realised by bidding firms Which are successful.

Those bidders whose offers are unsuccessful... can experience abnormal

losses as resources are dissipated" .11

2. TAKEOVER OFFERS AND SHARE PRICE ADJUSTMENTS

For any takeover offer, a bid price (including costs)12 can be envisaged where

the expected return to the offeror is that normally expected for the risk

inherent in the acquisition. At such a price, the acquiring firm's shareholders

can expect no excess return in an efficient market. By contrast, a bid price can

be contemplated that is above or below the normal, or equilibrium, level. A

number of questions then follow. For example, what returns can a shareholder of

an of feror firm expect on the unanticipated announcement of a takeover? What

return is expected for an offeree firm? Are the returns conditional on the bid's

success?

The answers to these questions depend on the market's interpretation of the

implications of the bid, and the speed with Which any information released by the

offer is incorporated into share prices.

in Australia, legislative barriers which restrict some firms'

entry into the takeover market. See, for example, the Companies (Foreign

Takeovers) Act 1972 and the Trade Practices Act 1974. Further, Australian

legislation restricts takeover activity in industries such as banking,

broadcasting and television and trustee management.

10. See p.79.

11. The acquisition cost on announcement for an eventually successful offeror

includes the discounted probability that the bid will fail and that certain costs

(e.g. legal expenses, auditing fees, the cost of managerial time and the cost of

complying with the information requirements of the legal system and stock

exchange listing) will be incurred for no return. These probabilities are

revised as the progress of the bid becomes known to investors. See pp.85-7.

12. Smiley (1976) estimated the cost in the u.S. of a takeover (including the

bid premium and managerial time) is of the order of 15 percent of the bid price.

66

Copyligl,L @ 2M 1 All Rigl,ts Qed

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

The Effieient Mapket8 Hypothe8i8 (EMH)

In an efficient market, prices respond rapidly to information.

13

Fama (1970) 14

identifies three forms of the EMH, depending on the particular information set

assumed to be available to the market. In its "weak" work the information set is

confined to the past series of share prices; in the "semi-strong" form, the

information set is publicly available information; and in the "strong" form, the

information set is all information relevant to the pricing of a security.

According to the EMH (in the "semi-strong" form), when information inherent in a

takeover announcement becomes publicly available, share prices instantaneously

adjust. The EMH does not rule out the possibility of excess returns accruing ex

post to the shareholders of either the acquiring firm or the acquired firm. It

predicts that market prices react immediately and without bias (Le. traded

prices are equilibrium prices) to the news of a takeover bid.

J. PREVIOUS EVIDENCE

The empirical evidence discussed in this paper is confined to those studies which

have employed models derived from the two parameter asset pricing model developed

by Sharpe (1964), Lintner (1965), and others. These studies are summarised in

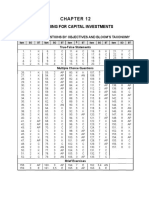

Table 3.1. Excellent discussions of earlier evidence are provided by Hogarty

(1970a), Dodd (1975), Henderson (1974), and Mueller (1977).

Hogarty (1970a, p.389) concluded his survey of early merger history (covering

mergers in the period 1904-1960), thus:

"what can fifty years of research tell us about the profitability of

mergers? Undoubtedly the most significant result of this research has been

that no one who has undertaken a major empirical study has concluded that

mergers are profitable, Le. profitable in the sense of being "more

profitable" than alternative forms of investment. A host of researchers,

working at dif ferent points of time and ut i lising dif ferent analyt ic

techniques and data, have but one major difference: whether mergers have a

neutral or negative impact on profitability."

Is this conclusion still valid for the evidence of the 1970s? Certainly, as it

related to Australian research on acquiring firms, it appears to be. Dodd (1976)

reports significant post announcement losses for offerors, results which are

anomalous with respect to the EMH. In contrast, major studies undertaken in the

United States by Mandelker (1974), Ellert (1976), and Dodd and Ruback (1977)

suggest that the United States share market is efficient with respect to the

informa tion inherent ina takeove r announcement. They are also cons istent wi th

the Internal Efficiency Hypothesis.

Studies summarised in Table 3.1 produced consistent results for the acquired

firms. Typically, after a period of excess negative returns, they experience

gains in the period leading up to and including the takeover announcement date.

Halpern (1973), Mandelker (1974), Dodd (1976), F;llert (1976), Firth (1976),

13. Strictly stated, the hypothesis is that share prices are continuously in

equilibrium; that is to say, the expected returns conditional upon acting on an

assumed information set are the same as the uncondi tional returns, ceteris

paribus.

14. Cf. Grossman (1976).

67

Co ri ht 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

Franks, Broyles and Hecht (1977), and Dodd and Ruback (1977) found similar

patterns for the CARs; patterns which are consistent with market efficiency.

Substantial gains in takeover negotiations are won by the shareholders of the

of feree finn.

An obvious question arises when comparisons are made between the results of the

more recent studies (based on risk-adjusted shareholder returns) and the previous

(in general, accounting-based) research:

15

can the conflicting results be

attributed to the differing modes of analysis?

It seems that a study of the same sample in both modes is unlikely to resolve

this issue as accounting numbers, under present accounting practice, are not able

to efficiently address questions on the timing of wealth changes. Schwert (1982)

argues that wealth changes could be isolated if accountants reported the economic

replacement cost of the finn. In general, because accountants report the

historical costs of individual assets, it is not possible to tEasure wealth

changes associated with say a takeover by relyirg on these data. Even if current

values reported conceptual problems exist.

l

The empirical evidence reviewed in this section, with the exception of Firth

(1976), was based on samples of the total population of takeover offers. Some of

these samples are selected with bias, for example, larger companies [Mandelker

(1974), Dodd (1976), Ellert (1976)].17 Most researchers have restricted their

attention to successful takeovers [Halpern (1973), Mandelker (1974), Ellert

(1976), Firth (1976), Franks, Broyles and Hecht (1977)]. A population of

Australian takeover offers, irrespective of the outcome is used in this study.

4. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

4.1 Data

All 572 takeover bids for more than half the outstanding ordinary shares of the

offeree, being an Australian listed company, and made between 1 January 1966 and

31 December 1972, are included in this study. The bids were identified from

Walker (1973), a schedule of delis ted firms prepared by the Sydney Stock Exchange

Limited, and tables published in The Australian Financial Review. Each bid was

classified as successful or unsuccessful, with success being defined as obtaining

a controlling interest (greater than half the offeree's ordinary shares).18

IT:Accounting -based studies which suggest takeovers are unsuccessful for

acquirers include: Reid (1968), Poindexter (1970), Laiken (1972), and Kuehn

(1975). A considerable amount of empirical evidence has been published since the

cut-off date for review used in the thesis on which this paper is based. This

evidence is reviewed in Jensen and Ruback (1983).

16. See, Schwert (1982, pp.146-147).

17. A reviewer correctly points out that since no one has incorporated

held and unlisted companies, all studies suffer from a size bias.

acquisitions are undoubtedly more important for economic management;

likely to involve large firms.

privately

Certain

these are

18. This criterion is necessarily subjective. Note, however, that complete

acquisition of offeree shares occurred in 251 of the 271 bids classified as

successful. It could be argued that the choice of fifty percent misclassified

some offerors as unsuccessful, Le., that control can be eKercised without

68

COPYright 2001 ATIRights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

There were 271 successful bids where both firms involved were listed, 112

successful bids where only the offeree was listed, 97 unsuccessful bids where

both parties were listed and 92 unsuccessful bids where only the offeree was

listed. Table 4.1 gives the time distribution of bids that were identified.

Table 4.1 is based on the announcement date of a bid, which is assumed to be the

date the bid was first publicly known. These dates were collected from The

Australian Financial Review, as also were the dates on which successful offers

were declared unconditional.

19

Weekly closing share prices, adjusted for changes in the basis of quotation,20

were collected for the period 1 January 1964 to 31 December 1974 for all firms

involved in successful bids and offerors whose bids were unsuccessful. Adjusted

prices 26 weeks either side of the announcement of the bids were collected for

offerees involved in unsuccessful bids. These data were screened for possible

errors by verifying all weekly returns greater than 20 percent in absolute value.

The primary sources for share price data were the official daily lists of the

Sydney and Melbourne stock exchanges. If a firm was not listed on these

exchanges, its share prices were collected from The Australian Financial Review.

The methodology also requires rates of return on a risk-free asset; and

preferably on an asset of one week maturity, since the share price data are

weekly. Such an asset is not readily available in Australia for the period

investigated. As a close substitute, the return on a 13 week (90 day) Australian

Treasury Note, which was the shortest term governmental (and thus virtually

riskless) security on issue during the whole of the investigation period, was

chosen. The time series was supplied by the Reserve Bank of Australia.

4.2 MethodoZogy

The analysis is conducted within the framework of the two parameter asset pricing

model developed by Sharpe (1964), Lintner (1965), and others from the seminal

work of Markowitz (1959). Black's (1972) version of the model states that assets

will be priced in equilibrium according to the following:21,22

majori ty ownership. The empirical importance of this classifying rule could be

assessed by stratification of unsuccessful transactions by proportion acquired.

Data for such a test was not originally collected, and subsequent attempts proved

fruitless.

19. Most Australian takeover bids were made conditional on a minimum acceptance

level (frequently 90 percent, as Australian company law allows compulsory

acquisition of dissenting shareholders' holdings iE 90 percent is achieved). In

such cases the unconditional date is normally the date acceptances total 90

percent, and can be regarded as the ultimate confirmation of the success of the

bid. Australian Associated Stock Exchange Listing Requirements (1978) require

shares of the offeree to be removed when 90 percent acceptance is achieved. This

date is, on average, 15 weeks aEter the announcement date.

20. As is customary with share price relative files, the dividend adjustment was

on a pre-tax basis.

21. For proof of this model see, Black (1972) and Jensen (1972).

22. Tildes (-) denote random variables.

69

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

( 4.1)

where expected (one-period) rate of return on asset i,

expected

weighted

economy,

return

return

on the market portfolio, Le., a

on the portfolio of all assets

value-

in the

expected return on an efficiently diversified portfolio whose

returns are uncorrelated with those of the market portfolio,

and

- - 2-

cov(Ri,Rm)/a (Rm) represents the risk of asset i relative of the total risks

of the market m.

Defining Bi = cov(Ri,R

m

)/a

2

(Rm) the model implies that E(Rit) (the expected

return on an asset i in period t) is equal to E(R

zt

) (the expected return on

a portfolio which is riskless with respect to the market portfolio), plus a risk

premium, that is [E(R

mt

) - E(Rzt)jRit. Thus the relationship between the

expected return on an asset and its risk (covariance with the market portfolio),

predicted by (4.1) is linear. Further cov(Ri,R

m

) is the only term in (4.1)

that is unique to asset i and hence it alone accounts for differences in

assets' expected returns. These predictions have been the subject of detailed

testing.

23

Suppose there exists a risk-free asset, with a single-period rate at which all

investors can borrow or lend unlimited amounts. This yields a special case of

(4.1):24

(4.2)

where Rf = the return on the riskless asset.

Equation (4.2) is stated in terms of expected returns, which must be replaced

with realised returns in empirical applications:

(4.3)

where Uit a residual or the excess return of security i in period t, which

is assumed to be uncorrelated with the market return.

The realised return for a security (Rit) contains

information concerning security i generated during

the return which is not accounted for by the return

securities [captured in Rft, (Rmt - Rft) and ~ t j

residual Uit providing

the total adjustment to

period t. That part of

inter-relationships among

will be observed in the

i. the event being investigated is independent of Rft and Rmt

23. -See, in particular Black, Jensen and Scholes (1972), Fama and MacBeth (1973),

and Ball, Brown and Officer (1976); but see Roll (1977).

24. See, Sharpe (1964) and Lintner (1965).

70

COPYright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

ii. the relative risk of security i is not affected by the event being

i nves tigated.

If takeover act ivity were not independent of general market movements, the

disturbance term could not be interpreted as capturing entirely the reaction of

share prices to the specific event being investigated. Since it has been

suggested that high takeover activity is associated with buoyant market -wide

conditions,25 the observed distribution of takeover bids per week is presented

below.

26

There are indications in Table 4.2 that there is some peaking of takeover

activity in the data; and therefore that there are dependencies through time.

27

The question of independence between takeover activity and market returns was

also investigated through correlation analysis. The frequency of takeovers in

the 28 three-month periods for which data were collected was correlated with

Rft, Rmt and (R

mt

- Rft). The derived Pearsonian correlation coefficients were

-0.02, 0.10 and 0.10 respectively. None of these is significant at the 5 percent

confidence level. Thus while takeover activity is associated with time, the

independence assumptions needed to estimate (4.3) are probably sufficiently well

met for the purposes of this study.

There is evidence to suggest that takeovers are associated with changes in

risk.

28

This can be expected as a takeover normally results in changes in

financial gearing and the asset mix. To allow for possible risk changes, ~ i t

is estimated using rates of re turn for the period (t -n*) to (t -1), where n* is

the number of rates of return used to estimate ~ i t 2 9 via equation (4.4).

R - R

i,t-n f,t-n

(4.4)

n 0, 1, 2, , n*

25. See, Nelson (1959), Bushnell (1961), Walker (1973), Kuehn (1975), and Stewart

(1977).

26. Table 4.2 summarises 479 bids, whereas the total number of bids investigated

in this study is 572, which includes multiple bids for the same offeree. The

data in Table 4.2 exclude a bid by a different offeror for an offeree which had

received a bid in the previous 10 weeks.

27. A chi-square statistic was calculated under the null hypothesis that

takeovers were generated independently through time according to a Poisson

process. The resultant chi-square statistic was 15.7. Were the null hypothesis

true, the probability of observing a sample chi-square statistic of 15.7 or more,

is less than 0.005.

28. See, Mandelker (1974), Dodd (1976) and Ellert (1976).

29. The optimal estimation period n* was determined by examining the mean

prediction errors, mean squared prediction errors and mean absolute prediction

errors for various n in the range 20 to 175 using all data in the file. These

results indicated there is little to choose between estimates using 50 and 100

weekly observations. The results reported below employ estimates of ~ using

the 100 prior observations. Note however that results are robust with respect to

~ estimation techniques. See, for example, Walter (1980), Appendix B.

71

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

The estimated systematic risk coefficient in (4.4), Bit' was calculated using

ordinary least squares regression. The (finn-specific) excess return in period

t is then given by:

(4.5)

Excess returns are averaged across securities for each week 't, which is defined

relative to the week in which a takeover bid is announced. Week 't, which is

not the same chronological week for all securities, is allowed to vary over a

range (such as 100 weeks before and after the week in which the event takes

place). That is,

AR

't (4.6)

where N is the number of takeover bids. Average excess returns are then

cumulated through the period investigated (from k weeks prior to the event date

to the end of any period 't), so that:

CAR

't

't

l: AR

t=-k 't

(4.7)

It is noted that the methodology carries with it two important qualifications:

a. three hypotheses - that (4.3) is descriptively valid, that the market is

efficient, and that takeovers have infonnation content - are jointly tested;

and

b. theoretically, Rm is the value-weighted index of ex ante one-period

returns on all assets in the economy.

In empirical investigations, a surrogate index must be used. The index chosen

for the results presented below is an equally weighted average of all rates of

return in the file, with the following exclusions:

i. for offeree companies, data for the 26 weeks prior to a takeover

announcement are excluded; and

ii. for offeror companies, data for the three years prior to a takeover

announcement are excluded.

There are, on average, 193 rates of return per week in this index. Dodd (1976)

reported excess positive returns of 37.1 and 25.3 percent over the six months

prior to a bid's announcement for the 58 acquired and 14 not acquired firms

respectively.30 His results were relied on for the exclusion period for offerees.

The offeror exclusion period was based on an inspection of the CAR and ARs for

all offerors and successful offerors derived under the assumption that fl=1.

31

These results revealed that offerors experienced excess positive returns over a

30. Prior to the six IIDnths, the monthly ARs were "small" and independently

distributed around a mean of zero.

31. In the absence of information about a specific security, this assumption

provides an unbiased estimate of its relative risk. The index used for this test

employed data for a random selection of 50 finns and is described in Brown and

Walter (1974).

72

OOl'yligl,t@2881 All Rigl,ts Reseived

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

period of approximately three years prior to a takeover announcement. This

period was excluded in the calculation of the index to compensate for the

systematic selection bias which exists in the total data file.

5. RESULTS: OFFEREES

Results are presented in this and the next section, in a standard format, as

follows.

a. A table is given which contains the Average Residual (AR) , the Cumulative

Average Residual (CAR), the total number of observations

32

in the AR, the

number of negative and positive residuals (excess returns), a z-statistic

and its related binomial probability (discussed e l o w ~ ~ and the average beta

of firms that have a residual in a particular period.

b. Two figures are included, the first of which presents the time series plot

of the CAR, and the second of which gives the time series plot of the

estimated beta of shares in the category irrespective of whether they have a

residual in a particular period.

34

c. There is a table of summary statistics from the Wilcoxon test (discussed

below)

d. The results in (a), (b), and (c) are discussed.

Signifioonce Tests

The statistical significance of the sign of the week-by-week residual is

determined using a binomial test.

35

As the number of observations increases, the

binomial distribution (the sampling distribution of the proportions observed in

random samples drawn from a two-class population) tends towards the normal

distribution.

36

For a population having equal proportions of positive and negative residuals, the,

reported probability is that of the sample proportion of positive residuals

differing from 0.5 by at least as much as the difference observed.

32. The number of observations is generally less than the population size because

of missing price relatives.

33. These are calculated using the 100 previous rates of return.

34. This procedure was adopted to prevent

introduced into each moving be ta series. Note

conducted on the mean of the estimated betas

offerees and offerors, and accordingly statements

only to the calculated averages.

artificial fluctuations being

that no significance test was

for the various categories of

about movements in beta relate

35. The test is described in Siegel (1956, pp.36-42).

36. Mood and Graybill (1963). The approximation is generally

reasonable when the number of observations is greater than 25.

(1956).

73

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

regarded as

See, Siegel

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

It could be debated whether the null hypothesis is appropriately one of equal

proportions. Brown and Hancock (1977) report that 49.4 percent of the non-zero

daily rates of return in the 4 days preceding and 5 days following the effective

announcement date of a profit report are positive. Similarly Brown, Kleidon and

Marsh (1980) report that 46.5 percent of the CRSP daily excess returns are

positive. The conclusion is that the binomial test as applied may be biased in

favour of rejecting the null hypothesis, because the population proportion of

positive excess returns is possibly slightly less than a half. Any bias will be

small, because it can be shown that the binomial test is not particularly

sensitive to moderate changes in the population proportions.

The Wilcoxon test is applied to test the significance of the observed movements

in the CAR over longer time intervals. A major purpose of this study is to

estimate the effect of takeovers on shareholder returns. As explained in the

previous section the methodology used involves averaging excess returns

calculated according to equations (4.5) and (4.6). Because these excess returns

are ex post observations of random variables, the average alone is not sufficient

to reach inferential conclusions about the true mean. A significant test is also

needed.

The parametric t-statistic is not obviously appropriate in this context because

it seems unlikely that excess returns are identically distributed across time and

across securities.

37

The significance test adopted here is the non-parametric

Wilcoxon Matched-Pairs Signed-Ranks Test (hereinafter the Wilcoxon test). The

Wilcoxon test does not assume identically distributed returns, though it does

assume independence and symmetry.38

The Wilcoxon test involved the selection of two control shares

39

for each share

involved in a takeover offer (the sample firm). Each sample share is matched

with a control portfolio such that they are of identical risk. Under the

assumption that the sample share's involvement in a takeover offer was the only

systematic difference between it and the control portfolio, the difference

between their cumulative rates of return is an unbiased estimate of the effect of

the takeover. For estimation efficiency reasons it was deemed that each share

must

t. have at least 90 percent of its price relatives available over the

investigation period, and

37. See, Ball, Brown and Officer (1976). Since the computing was conducted for

this paper accepted methods of statistical analysis have undergone considerable

change. This change towards the use of t statistics in significance testing can

be attributed to the analysis conducted by Brown and Warner (1980).

38. See, Siegel (1956, pp.75-83). The test is applied to continuously compounded

returns to conform better with the symmetry assumption. Cf. Brownlee (1956).

39. Two acceptable control shares (the ones with ~ i immediately above and below

the sample) were used for each share, to guarantee estimated betas that were

identical. This procedure was adopted to overcome a possible problem in applying

the Wilcoxon test: matching of control and sample shares on ~ i may result in

significant differences in average betas occurring by chance. The weights used

to equate portfolio estimated betas with sample ~ i S were applied to individual

control security returns to determine the weekly return of the control portfolio.

74

COPYright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

ii. not be involved in a takeover offer in the period 100 weeks either side of

the sample share's announcement date before it was considered acceptable as

a control share.

The null hypothesis is that the sample and its control are drawn from the same

population, and the Wilcoxon probability reported is the (two-tailed) probability

of observing the (signs and ranks of the) cumulative rates of return on the

sample shares and their respective controls, if the null hypothesis were true.

These probabilities are reported for

1. the period -100 to -1, that is, the pre-announcement period excluding the

announcement week;

ii. the period -100 to 0, that is, the total pre-announcement period including

the announcement week; and

iii. the post announcement period, that is, +1 to +20 (for offerees)40 and +1 to

+100 (for offerors).

In addition, the number of cases in which acceptable pairs were found and the

difference in the average return between each sample and control portfolio are

reported for each investigation period. When the difference in the average

return is multiplied by the number of weeks in the investigation period, an

alternate (to the CAR) measure of excess returns is derived.

41

Results are presented for the following groups of offerees:

1. All 572 offerees which received a takeover bid during the investigation

period, that is, from 1 January 1966 to 31 December 1972 (Table 5.1.1).

2. All 383 offerees which were successfully acquired

42

(Table 5.2.1).

3. All 189 offerees which were not acquired (Table 5.3.1).

40. The Australian Associated Stock Exchange Listing Requirements stipulate an

offeror must notify the exchange as soon as acceptances reach 90 percent. The

shares of the offeree are then removed from trading. Consequently, the number of

firms for which data exist, in the category of successfully acquired offerees,

drops from 215 on announcement to 51 in week +20. See Table 5.2.1.

41. While the Wilcoxon test is unbiased, the cumulative mean difference between

the sample and control rates of return (i.e., the "sample return less pair return

averaged" - refer tables, following) can depart substantially from the CAR

computed over the same period. The reason is that the variance of the CAR is

approximately N times the variance of the AR, where N is the number of weeks

over which the series is accumulated. Since the variance of the AR varies

inversely with the number of shares used to compute it, departures can be

"substantial" in small samples. See, for example, Table 6.3.1 and 6.3.2.

42. Success is defined as gaining control of more than 50 percent of the

outstanding ordinary shares of the offeree.

75

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

5.1 All O f f e ~ e e

Table 5.1.1. presents results for 572 separate bids where a separate bid is

defined to include the case of a different offeror bidding for the same offeree.

The CAR accumulates 5.5 percent in the period -100 to -10. In this period 45 of

the ARs are negative, 46 are positive. In 8 of the 91 weeks the z-statistic for

the binomial test is significant at the 0.05 confidence level; perhaps not

surprisingly, the proportion of positive residuals is less than half in each of

the 8 cases.

In contrast, the ARs in the period -9 to -0 are uniformly positive; four of the

z -statistics are significant at the 0.05 confidence level. The CAR rises 27.7

percent during this period; 12.9 percent of this rise occurs in week O. Eighty

percent of the residuals in week 0 are positive. Indeed, the probability of

observing the disproportionately high number of positive residuals in either week

-lor week 0 is very close to zero. Note that the binomial test in this case is

if anything biased against rejecting the null hypothesis.

After a period of "about normal" return (in the period -90 to -40 the CAR

declines one-half percent) offerees show sharp rises in excess positive returns.

The Wilcoxon test indicates that the probability of the difference between the

sample and control excess returns being as large as that observed under the null

hypothesis that each sample and its control are drawn from the same population,

is less than one in one thousand.

Some of the average excess return in the immediate pre-announcement period is

explained by the entry of competing offerors.

43

The results in Table 5.1.1 relate

to 572 separate bids, where a separate bid includes the case of a different

offeror bidding for the same offeree.

44

The average excess return may also in

part be associated with market purchases by the offeror prior to the announcement

of the bid, or to investor anticipation of an imminent offer. Takeover bids

undoubtedly involve a period of planning by the offeror and information may be

released during this planning stage.

After a takeover bid announcement the CAR increases by a further 1.9 percent of

which 1.5 percent occurs in week +1. The week +1 residual could be associated

with non-trading.

45

If a bid is announced in a particular week after the last

sale in the data file, the residual of week +1 captures the market adjustment to

information which became available in week O. Thus a positive AR in week +1,

even were it significant, should not be regarded as evidence of a slow reaction

to the news of a takeover bid. In any event the Wilcoxon test computed

probability of 0.433 for the period +1 to +20 suggests that any differences in

return between the sample shares and their respective controls could easily be

due to chance. Further, no z-statistic in this period is significant at the 5

43. Eliminating competing offeror bids (made in the previous 50 weeks) for the

same offeree reduces the number of cases in this category to 442. This results

in vi rtually no change to the general tenor of the reported sample, save the

obvious reduction in numbers of observations. These 'single bid' results are

available on request to the author.

44. There were 93 cases in which there was a bid by a different offeror for an

offeree which had received a bid in the previous 10 weeks (refer Table 4.2).

45. Non-trading in week 0 will bias the Wilcoxon test towards rejection of the

null hypothesis in the period (+1; +20).

76

CopYright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

percent confidence level.

The time series plot oAf the moving beta series (Figure 5.1.2) reveals 11 ttle

change in the average for this group.46 Average computed beta varies between

0.92 and 0.87 in the pre-announcement period and falls to 0.82 by week +20.

A final comment concerns evidence available which confirms the appropriateness of

the exclusion criterion used to estimate the systematic risk of offerees (26

weeks of data prior to an offer were excluded). The proportion of positive

residuals for offerees in the period -100 to -53 was calculated, and this was

assumed to be the population proportion for the purposes of a binomial test on

the observed proportions in the subperiods -52 to -27 and -26 to O. The

resultant z-statistics were 0.57 and 7.56 respectively, leading to rejection of

the null hypothesis at the 5 percent confidence level for the latter sub-period,

but not for the former.

5.2 SueeessfuZ Offepees

Table 5.2.1 present offeree results for 383 successful bids. Uncanny investor

foresight would have to be assumed for us to claim that the success of the bid

was determined at the bid announcement date. Hence much of the discussion which

follows must be hedged carefully. It is worth nothing that there are instances

of bids by unsuccessful offerors preceding successful bids.

47

The pattern of the CAR is similar to that of Table 5.1.1. The CAR rises 7.2

percent during -100 to -10, and by a further 28.0 percent from -9 to 0 (the AR in

week 0 is +13.5 percent). There are only seven weeks out of ninety weeks in

which the proportion of negative residuals significantly exceeds half at the 5

percent significance level over the period -100 to -10, but there are four out of

ten weeks in which the proportion of positive residuals significantly exceeds

half in the period -9 to 0, at the 5 percent significance level. The Wilcoxon

probability over the period -100 to 0 is again less than .0005. Presumably this

is mainly due to the behaviour over the period -9 to O.

The CAR rises a further 1.7 percent in the period +1 to +20, 1.5 percent of which

occurs in week +1. Non-trading cannot be ruled out as an explanation of the week

+1 AR. The Wilcoxon test yields a probability of 0.596 that the results could

have been observed were the control and sample drawn from the same population.

The binomial test yields no instances of disproportionately positive residuals in

this period, that are significant at the 5 percent level.

5.3 UnsueeessfuZ Offepees

Table 5.3.1 reports results for 189 offerees where the bid was eventually,

despite revision and competition in some cases, unsuccessful. 48,49 Over the

tests on beta-shifts were not conducted.

47. Eliminating those cases of previous (unsuccessful) bids in the prior 50 weeks

reduces the sample size to 353. Not surprisingly (given only 30 eliminations)

these single bid results are almost identical.

48. Exclusion of bids for the same offeree in the previous 50 weeks in cases of

revision or competing offeror involvement reduces sample size to 89. Non-trading

and the data collection procedures described in fn 49 below cause available

observations to be less than 20, and comment seems inappropriate. See also

fn 53.

77

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

period -100 to -30 the CAR declines 7.3 percent, and then rises 27.4 percent in

the period -29 to O. After a period of excess negative returns this groups

experiences considerably improved returns. The AR in week 0 is +10.2 percent,

compared to 13.3 percent excess return for offerees successfully acquired. For

unsuccessful offerees the binomial probability in week 0 is in contrast with that

of Table S.2.l. Approximately 40 percent of the residuals in week 0 are

negative

SO

for offerees not acquired, compared to approximately 17 percent for

those acquired. There is some suggestion in this comparison of differential

investor reaction. The Wilcoxon statistic does not lead to the rejection of the

null hypothesis at the S percent level, in contrast to the binomial test, and to

the results for acquired offerees.

The CAR rises 2.8 percent over the post-announcement period; 2.1 percent of the

rise occurs in week +1. By week +S the CAR rises S.4 percent and then declines

2.6 percent by week +20. This rise and subsequent decline could be explained by

bids being revised upwards, followed by share price declines as the unsuccessful

outcome of the initial bid and its subsequent revisions ultimately becomes known

to the market.

Sl

This explanation cannot be offered with any assurance, as there

are competing informational cues flowing to the market in the post-announcement

period.

52

Despite the bids' lack of success (recall that hindsight is used in making this

judgement), the CAR does not decline in the overall post-announcement period.

Thus unsuccessful bids must convey, or prompt the conveyance of, information

49. Data collection for this group was limited to 26 weeks either side of the

announcement but results are presented 100 weeks prior to announcement as many of

these offerees are in other takeover categories, I.e. they either make bids or

are not acquired in other takeover offers. Further, non-trading (this category

contains many "smaller" companies) reduces the number of available observations.

so. Corresponding figures for weeks -2 and -1 are 30 percent and 24 percent

respectively. Both are significant at a = O.OS.

Sl. Revisions occurred in 17 percent of cases where a bid was eventually

successful, and in 16 percent of cases where it failed. Corresponding figures

given by Walker (1973) are 14 percent and 21 percent. While the data for this

study suggest that revisions do not occur more frequently for unsuccessful bids

(and that the expectation of a revision is a fair game for all offers), there is

eVidence in Walker's data that revisions are expected more frequently in ex post

unsuccessful bids.

S2. There are 43 firms of this category where only one unsuccessful bid was

received in the period 50 weeks either side of the identified bid date. However,

due to non-trading, the number of available residuals for this "single-bid" group

is on average less than ten. In the period -100 to -40 the CAR declined 10.S

percent, and then rose 43.3 percent to be +32.8 percent at time 0 (18.5 percent

of this rise occurred in the announcement week). By week +20 the CAR was +22.7

percent, which is consistent with a "rational revisions of expectations of

eventual takeover" hypothesis. Note however, these results depend on

considerable hindsight and further, a fair game cannot be constructed for firms

so identified. It is not until the end of the 50 week period that it is known a

competing bid was not made, and this identification with hindsight violates the

fair game model.

78

COpyi igl it @ 200 I All ~ i g r l l F<eselveC!

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

which causes permanent revisions to share prices. If we characterise a share's

price as being set by the market in accordance with some prior distribution of a

future successful bid being received, then the receipt of an unsuccessful bid

causes a shift in this prior distribution. Walker (1973, p.9) reported that

"approximately 38 percent of companies listed on the Sydney stock exchange at

some stage during 1960-1970 were subject to a bid during that eleven year

period". Of the 189 unsuccessful bids in Table 5.3.1, 112 are, within a period

of two years, followed by successful acquisitions.

53

Based on these relative

frequencies plus our knowledge that two in three of the bids studied are

successful, there is a probability of .38 that a successful bid will be received

in a one-year period conditional upon an unsuccessful bid having just been

rejected; while the unconditional probability of a successful bid being received

over the same period is less than a tenth as great.

The time-series plot of average moving beta (Figure 5.3.2) depicts a pattern

similar to that of the two previous offeree groups. Average estimated risk

varies little throughout the investigation period.

Conclu8ion8 fop Offepee8

Typically shareholders of offerees, after experiencing a period of average or

below average investment performance, enjoy excess positive returns over the 20

weeks up to and including the takeover announcement week. Most of these gains

accrue in the announcement week. Following the announcement, returns consistent

with a rapid and unbiased adjustment to new information released in the takeover

announcement, are observed. These results are consistent with the evidence

provided by Dodd (1976), Bradley (1977), Dodd and Ruback (1977) and Firth (1978).

Over the investigation period there is "little" change in the

relative risk to offeree companies. Estimated risk varies

percent for all of ferees over the pre-announcement period.

exist for the acquired and not acquired categories.

Implication8 fop Takeovep Hypothe8e8

i. The Efficient Mapket Hypothe8i8

estimated average

by less than six

Similar patterns

Capital market efficiency with respect to takeover announcements is primarily

concerned wi th the behaviour of pos t -announcement res iduals. 54 Capi tal ma.rke t

53. For these 112 the CAR (calculated by setting equal to one to overcome

some data shortage problems) rises by 4.2, 0.9, 4.9, 8.6, and -0.8 percent

respectively in each of the 10 week periods following announcement. For the 77

which were not subject to a successful bid corresponding 10 week post-

announcement CARs are -2.5, -1.9, -9.0, 3.3 and 2.7 percent. Over this 50 week

period the subsequently acquired group CAR rises 17.8 percent, compared to a 7.4

percent fa1l for the not acquired group. Clearly fair game implications are

violated here but these results shed some light on whether efficiency gains

result from attempted takeovers. In this context note that the rise in the CAR

for the 77 firms in the 10 week pre-announcement period is 26.6 percent, and, by

implication, some permanent gains are evident.

54. Pre-announcement residual behaviour is of some interest in that it can be

used to determine when information flows to the market. Takeover bids are

planned by management of the offeror over some period prior to public release.

In many cases the of feree' s management i.s invo 1 ved 1n pre -announcemen t

79

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

efficiency implies that market prices reflect all publicly available information,

consistent with a theory of market price equilibrium. Provided there is no ex

post sample bias induced either by the estimation methods or by the impact of

information released subsequently to the bids, the observed post-announcement ARs

should be independently distributed around a mean of zero. They were.

ii. Hypotheses

The gains experienced by offerees are maintained, irrespective of bid outcome, in

the post-announcement period. These offeree results are consistent with the

Internal Efficiency Hypothesis, where offerees are presumed to own unique

resources. Information on the availability for sale of these unique resources

causes offerors to compete for control of the offeree through acquis\tion.

There is evidence in the pre-announcement ARs and CAR that these unique resources

may be under-utilised or inefficiently managed assets. 55 Offerees experience

negative excess returns over periods of approximately 50 weeks in the pre-

announcement period.

56

Whatever these unique resources may be, the announcement

of a takeover offer conveys information concerning the offeree, regardless of the

outcome of the offer.

The permanent gains from unsuccessful bids is an empirical implication of the

Internal Efficiency Hypothesis that allows it to be distinguished from the

traditional takeover hypotheses, under which gains are conditional on a

successful acquisition. The results give some indication of permanent gains to

all offeree categories and are thus not consistent with the empirical

implications of the traditional synergy and monopoly rents arguments.

6. RESULTS: OFFERORS

This section discusses the results for offerors

57

in the following categories:

1. all offerors, irrespective of the outcome of the offer (368 cases);

2. offerors whose bids are successful (271 cases);

negotiations. If a market is efficient in the "strong" form, news of a takeover

would be impounded into prices prior to its public release. That there are some

anticipatory price increases prior to the official release can be taken as an

argument that the market is able to discover some information prior to its public

release. However, the concern here is with testing the EMH in its "semi-strong"

form.

55. A special case of the Internal Efficiency Hypothesis is that takeovers are a

means of disciplining inept management. See Manne (1965) for an exposition of

this argument.

56. For category (a) (572 offerees) the CAR declines from 0.015 to 0.010 over the

period -90 to -40; for category (b) (383 acquired companies) the CAR declines

from 0.020 to 0.012 over the period -89 to -44; for category (c) (189 offerees

not acquired) the CAR declines over the period -100 to -30 by 7.3 percent.

57. The post-announcement investigation period for offerors is extended to 100

weeks; in other respects the results follow the format described for offerees.

80

Copyfight 2UU1 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

3. offerors whose bids are unsuccessful (97 cases).

In addition summary results for various sub-categories of the population of

successful offerors are presented. These sub-categories were drawn to offer

additional evidence on the anomaly reported by Dodd (1976).

6.1 All

The CAR for all 368 offerors accumulated 30.7 percent in the period -100 to O.

There are thirteen significant (at ex = 0.05) binomial probabilities in this

period, eight of which are associated with excess positive residuals. The

Wilcoxon probability is less than 0.001, which indicates that it is extremely

unlikely that the results are due to chance. The pre-announcement offeror CAR

contrasts the offeree results, as too does the week 0 Average Residual (AR) of

-0.3 percent. In the announcement week the computed binomial probability of

0.85, again is in contrast to the offeree result. There is no evidence of

positive excess returns for offerors on the announcement of a takeover offer. In

the 100 week post-announcement period the CAR rises a further 2.0 percent, but

the Wilcoxon test does not indicate any systematic difference between sample and

control at the 5 percent confidence level.

The average for this group rises over the period, by approximately 11

percent: from approximately 0.98 at week -100 to 1.04 per week 0, and 1.09 at

week +100.

6.2 Sueeessful

Table 6.2.1 summarises the results for 271 offeror firms which acquire the bid-

for offeree.

58

The CAR rises over the period -100 to 0 to 28.2 percent. In this

period twelve binomial probabilities are significant at ex = 0.05; eight of them

are associated with excess positive residuals. The Wilcoxon test indicates that

the pre-announcement CAR behaviour is highly unlikely to be observed were the

null hypothesis true.

In the period +1 to +100 the CAR declines 1.5 percent with four binomial

probabilities significant at the 5 percent level, all associated with negative

residuals. The computed Wilcoxon probability is .084.

59

Despite this "relatively

low" Wilcoxon probabili ty, the ARs in this period are "small". Moreover, 48 are

positive and 52 are negative.

0 is the date a takeover bid was announced. Recall that, for a

definitive test of capital market efficiency for successful offerors, residuals

should be cumulated either side of the date of public knowledge of the offer's

success. The results derived using the unconditional (I.e. 90 percent

acceptance) date are similar to those reported in Table 6.2.1. This

unconditional date in many cases occurs after the effective public knowledge

date, as the release of percentage acceptance figures allows the predicti.on of

success prior to its ultimate confirmation. The unconditional date on average is

15 weeks after the bid's announcement.

59. The sample return less the pair return averaged per period was -0.0005. This

implies a 5 percent greater return for paired firms over the 100 weeks, compared

to only 1.5 percent using the Rf version of the market model.

81

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

In the period -1 to +1 the CAR declines 1.3 percent. This adjustment is

consistent with the hypothesis that the identification or confirmation of a firm

as an offeror is on average viewed as a disappointment.

60

When it makes a

takeover offer, an offeror simultaneously releases information that it is not an

offeree and that it will not participate that week in the excess positive returns

offerees typically experience when they receive a takeover offer. Ceteris

paribus, survival could be viewed as a disappointment! The negative ARs in week

o and +1 are consistent with such a "survival disappointment hypothesis".

Further, the slight though statistically insignificant drift in the post-

announcement CAR can be explained by continued survival and further takeover bids

by surviving offerors.

61

Given that offerors on average earn zero or slightly negative abnormal returns in

the results discussed to here, cross-sectional statistics on offeror returns in

the post-announcement period are presented in Table 6.2.3.

The point at issue here is an expectation that different returns will accrue to

different offerors reflecting market expectations as to firm specific synergistic

benefits from the takeover. For example, it may be expected that firms which

have a history of acquisitions will exhibit different abnormal returns to those

that make rare acquisitions, as expectations di f fer acros s the groups. From

Table 6.2.3, even though announcement week returns are on average negative, 30

percent of those offerors have excess positive returns of greater than 1.33

percent, while 10 percent have positive excess returns greater than 4.38 percent.

Clearly, some takeover announcements are viewed as good news for offerors. For

the takeover period, i.e. from announcement date to the lIDconditional date, 50

percent of offerors have positive abnormal returns.

The average ~ rises over the Whole period (-100 to +100) by approximately 10

percent. The post-announcement rise of seven percent occurs despite the

acquisition of shares with lower systematic risk

62

(the average Ili of offerees

at week 0 is approximately 0.87). Galai and Masulis (1976) demonstrate, among

other things, that the systematic risk of a firm's equity is a positive function

of the firm's leverage, as shown by Hamada (1972), and a negative function of the

value of the firm, the riskless rate of interest and the variance of the firm.

Further, the merger of two firms with less than perfect correlation of returns

will decrease the variance of the new (combined) firm. Hence systematic risk of

a combined, lower variance firm can exceed that of the merging parties.

60. ITall share prices for all firms included in an index are available, then

the average residuals of all firms over all periods covered by the index (derived

from a market model regression) must by definition of the ordinary least squares

regression technique, sum to zero. Given that there are firms in the index with

positive excess returns associated with (say) receipt of takeover bids, then

other firms not receiving bids must have, on average, negative residuals.

61. For example, Sla ter Walker Securi ties (Austr!Jlia) Limited, Dunlop Australia

Limited and Industrial Equity Limited made ten, nine and eight successful bids

respectively.

62. The systematic risk estimates of offeror companies may be biased towards

zero, due to the non-trading effect being greater for smaller companies. See

Dimson (1979).

82

COPYright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

6.3 Unsuccessful Offepops

Table 6.3.1. presents results for 97 offerors whose bids are eventually

rejected.

63

The CAR rises 44.0 percent in the period -100 to 0 and then rises an

additional 21.3 percent in the period +1 to +100. Were the null hypothesis true,

the (Wilcoxon test) probabilities of observing results at least as strong as

these are 0.003 and 0.006 respectively. Unsuccessful offerors in the pre- and

post-announcement periods are thus inferred to earn returns that are

significantly greater than the control firm returns. Yet the week-by-week

Binomial probabilities behave as expected. In the pre-announcement period four

are significant at a: = 0.05 (one associated with excess negative residuals and

three with excess positive residuals); in the post-announcement period six are

significant (three associated with excess positive residuals and three with

excess negative residuals). The data files were checked for the incidence of

post-bid announcements that could explain the post-bid pattern of returns.

The following post-bid announcements

64

were made in the period +1 to +100 by the

97 unsuccessful offerors:

i. 57 firms made at least one bonus or rights issue. There were (58) separate

bonus issues and 24 rights issues altogether;

ii. 15 firms were themselves either acquired (12) or received bids (3) for

complete acquisition;

iii. 2 firms announced returns of capital to shareholders;

iv. 23 firms did not make announcements of the above nature. Of the 23, 15

announced dividend increases, two announced dividend reductions and six made

no change.

The dividend files reveal that of the 88 firms for which dividend histories exist

(9 firms were acquired before the next dividend payment was due):

63. Note that results here are for 100 weeks either side of the announcement date

of a takeover. This date is hardly likely to be the data of public knowledge

that "Company x is an unsuccessful offeror". Since the "unsuccessful" label is

attached with hindsight, these results are not derived in the context of a fair

game. Unsuccessful offers typically involve protracted negotiation periods, in

some cases extending more than two years. Further, the date of public knowledge

cannot be pin-pointed with any assurance; several percentage acceptance figures

are released in the post-announcement period, and it is probable that, like

success, failure was predictable prior to the eventual withdrawal date in many

cases. Again, although offeree company directors' recommendations to

shareholders are closely related to a bid's final outcome [Walker (1973) found

that 92 percent of the takeover bids studied succeeded or failed in accord with

directors' final recommendations], those recommendations do change during

negotiations (Walker (1973) reports 38 instances (15 percent of all reject

recommenda t ions) of di rectors' recommenda t ions changi ng from "reject" to

"accept").

64. The term "announcement" is used somewhat loosely. The data files contain

ex-dividend and rights dates rather than actual announcement dates. However most

of the announcements would have been made in the post-bid period.

83

Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

i. 63 firms increased dividends at least once in the 100 weeks post-bid:

ii. 13 made no change (5 of these did not pay any dividends):

iii. 6 increased dividends and subsequently reduced them:

iv. 6 reduced dividends.

All of the above announcements are captured in the residuals for the post-

announcement period and are associated with positive excess returns for the

re<;pective populations of all such announcements: Ball, Brown and Finn (1977)

find positive excess returns of 20.2 percent for bonus issues and 9.7 percent for

rights issues in the twelve months prior to announcement: offeree positive excess

returns are approximately 30 percent in the 20 weeks prior to a takeover

announcement; and Brown, Finn and Hancock (1977) report gains of 17.1 percent

over the year prior to a dividend increase announcement, and losses of 22.4

percent for dividend decreases.

Before the informational releases described above can be offered as an

explanation of the post-bid excess returns, it must be shown that they occurred

more frequently than expected in a fair game: that is, that they occurred more

frequently than expected for offerors in general until such time as progress on

the bid allows categorisation of an offeror as unsuccessful: and from then,

showing that in the time period studied (1966-1972) they occurred more frequently

than expected for the population of all unsuccessful offerors. To shed some

light on this expectation the unsuccessful offerors were split into two groups,

comprising

i. the first of 48 bids, and

ii. the later 49 bids.

The split of information releases is considered in Table 6.4. Assuming the first

half proportions are expectations for the second half bids, then the conclusion

from Table 6.4 is that we should not reject the null hypothesis (that the

observed second half proportions were drawn from a population with proportions

equal to those in the first half). The implication of the conclusion is that the

anomalous behaviour is not due to the "seemingly large amount of good news".

The explanation appears to be that the sample is dominated by the inclusion of

Industrial Equity Ltd. (IEL) at a critical point in that company's extraordinary

history. IEL made 10 unsuccessful bids in the period studied (and 8 successful

bids). The average positive excess return of lEL over the period (+1, +100) was

84.97 percent.

65

lEL's impact on the aggregate results for the 97 unsuccessful

offerors (calculated over the 43 companies for which returns could be calculated

on average each week) was to increase the CAR for (+1, +100) by 19.84 percent.

Thus only 1.5 percent of the post-announcement rise of 21.3 percent is not

associated with the inclusion of lEL.

That the revealed post-announcement behaviour of the CAR is dominated by extreme

outliers is further confirmed by considering the signs of the residuals over the

whole of the post-announcement period. Over this period there are 1967 positive

residuals and 1975 negative residuals. Using an expected equal proportion of

calculation for lEL's impact on the CAR for successful offerors

yields, +0.83 percent, which does not alter the tenor of the results.

84

copyrlgllt 200 I All Rights Reserved

at University of Technology Sydney on February 13, 2013 aum.sagepub.com Downloaded from

WALTER: TAKEOVERS

positive and negative residuals, a Binomial probability of .90 suggests extreme

outliers have dominated the results.

Conclusions for Offeror Categories

Offerors experience positive excess returns throughout the investigation period

prior to a takeover announcement. This result is consistent with the direction

but not the magnitude of excess returns reported by Mandelker (1974), Dodd

(1976), Ellert (1976) and Dodd and Ruback (1977). Successful offerors experience

gains of approximately 14 percent per year over the two years prior to a bid

announcemen t .66

The average rises for all offeror categories over the investigation period,

despite the acquisition of offerees with lower average Changes in estimated

risk are also found for unsuccessful offerors. If the sample estimates are

correct, then the repackaging of the firm's financial characteristics, typically

associated with a takeover, could explain the increasing systematic risk.

ImpZieation Hypotheses

i. The EMH

The post-announcement analysis reveals no significant evidence of excess returns

to offerors following their bids, and is consistent with Mandelker's risk-

adjusted result. Dodd's result again contrasts the post-announcement period

results of this study. The 136 successful offerors studied by Dodd have excess

negative returns of seven percent per year in the two years following the bid,

results which are anomalous with respect to market efficiency, provided the

announcement predates the negative returns. That anomaly is not present in this

study.

Unsuccessful offeror post-bid results also contrast the evidence of Dodd.

Positive excess returns of 10 percent per year are reported here; Dodd reports no

systemati.c excess returns from month +2 to +24, after an abnormal loss of four