Professional Documents

Culture Documents

From Human Resource Strategy To Organizational Effectiveness: Lessons From Research On Organizational Agility

Uploaded by

ec01Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

From Human Resource Strategy To Organizational Effectiveness: Lessons From Research On Organizational Agility

Uploaded by

ec01Copyright:

Available Formats

Learning Organizations: A Methodology for Organizational Effectiveness

Darren Zink Supervisor: Teresa Rose

April 2, 2007

Applied Project Athabasca University Word Count 18,782

Zink, 2

Abstract

This conceptual paper provides a critical analysis of how Learning Organizations can drive effectiveness in organizations. The concept of the Learning Organization is that the successful organization must and does continually adapt and learn in order to respond to changes in the environment and to grow. This raises a range of scholarly and theoretical questions relating to what it means for an organization to learn, and practical questions around what organizations need to do in order to learn and adapt. (Wikipedia, 2007) The objective of this study is to investigate these questions while offering credence as to why Learning Organizations are a must. The paper is divided into 3 distinct sections. Firstly, it commences with a background of learning frameworks, complemented with an understanding of why they are critical and the various barriers that exist in the modern business world. Subsequently the key issues are identified followed by analysis that includes how communication, leadership, commitment, and teamwork variables figure into Learning Organization frameworks. Secondly, a new integrated learning model, termed OLM (Optimized Learning Model), is introduced to address the gap in the academic world whereby an implementable learning model is evidently lacking. The theories of leading learning thinkers, including Peter Senge, David Cayla, Robert Flood, Nick Bontis, and Popper & Lipshitz, are then investigated in relation to OLM. Thirdly, recommendations for implementation are also provided for OLM and beyond. The writings of Dr. Prasad Kaipa are employed as the foundation for this portion of the report. Specific executables from Susan Heathfield are also incorporated in this section.

Zink, 3

1.0 Table of Contents

2.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................5 2.1 BACKGROUND........................................................................................................................5 2.2 CHALLENGES IN TODAYS ENVIRONMENT ...............................................................................7 2.3 WHAT IS ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING?..............................................................................7 2.4 WHAT IS A "LEARNING ORGANIZATION"? ...............................................................................8 2.5 WHY IS A LEARNING FRAMEWORK CRITICAL TO ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS? ..............9 2.6 BARRIERS TO LEARNING ORGANIZATIONS ............................................................................13 3.0 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES AND STUDY PURPOSE ..............................................13 4.0 WHY TEAMS TRUMP INDIVIDUALS IN THE 21ST CENTURY ...............................15 4.1 UNIFORM QUALITIES WITHIN EFFECTIVE TEAMS ...................................................................15 4.2 SHARED VISION WITHIN TEAMS ...........................................................................................16 5.0 LEADERSHIP AND DRIVING LEARNING DISTINCTION.......................................17 6.0 GAINING COMMITMENT.............................................................................................18 7.0 CULTURE AND THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION.................................................20 8.0 THE BIRTH OF A NEW LEARNING MODEL - OLM ................................................21 8.1 A MODEL FOR LEARNING EXCELLENCE - OLM ....................................................................22 8.2 EXAMINING THE MODEL OLMS FUNCTIONALITY ..............................................................23 8.2.1 Leadership................................................................................................................23 8.2.2 Learning ...................................................................................................................24 8.2.3 Project Management.................................................................................................25 8.3 OLMS CONTRIBUTIONS AND SHORTFALLS...........................................................................26 8.4 SENGE OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON TO OLM ..................................................................28 8.4.1 Realizing Senges Five Disciplines............................................................................28 8.5 CAYLA OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON TO OLM..................................................................31 8.5.1 Learning at Level I....................................................................................................31

Zink, 4 8.5.2 Learning at Level II ..................................................................................................32 8.5.3 Learning at Level III .................................................................................................33 8.6 FLOOD OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON TO OLM..................................................................34 8.7 BONTIS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON TO OLM .................................................................35 8.8 POPPER & LIPSHITZ OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON TO OLM ..............................................36 9.0 EXECUTION BRINGING OLM TO LIFE ..................................................................39 9.1 STEP 1 CREATING A FOUNDATION......................................................................................40 9.2 STEP 2 ESTABLISHING A NEW CULTURE .............................................................................42 9.3 STEP 3 INDIVIDUAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL TRANSFORMATION ..........................................43 9.4 STEP 4 DESIGNING A NEW GAME .......................................................................................44 9.5 SPECIFIC TACTIC RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................45 10.0 PITFALLS TO AVOID IN IMPLEMENTATION........................................................46 11.0 CONCLUSION................................................................................................................48 12.0 KEY LEARNINGS..........................................................................................................48 13.0 APPENDICES .................................................................................................................50 13.1 APPENDIX A. CHRONOLOGY OF LEARNING ORGANIZATION CONCEPTS .............................50 13.2 APPENDIX B. - CHARACTERISTICS OF A LEARNING ORGANIZATION AND ASSOCIATED BEST PRACTICES.................................................................................................................................54 13.3 APPENDIX C. LEARNING ORGANIZATION MODELS ...........................................................56 13.4 APPENDIX D. OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH METHODS AND RESOURCES APPLIED IN THIS STUDY .......................................................................................................................................58 14.0 REFERENCE LIST ........................................................................................................60

Zink, 5

2.0 Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to provide substantive support for why organizations should move towards adopting Learning Organization (LO) frameworks, while presenting a capable strategic and implementable model for how to achieve this objective. The analysis herein focuses on why learning frameworks are essential in todays business world. The fact that organizations far and wide have neglected to embrace learning is the key issue exposed, thus strategy and implementation recommendations for driving learning excellence is an appropriate critical response to this challenging issue. But why should we be concerned at all with current management trends in the business world? Our prevailing system of management has destroyed our people, writes W. Edwards Deming, leader in the quality movement. People are born with intrinsic motivation, self-esteem, dignity, curiosity to learn, joy in learning. On the job, people, teams, divisions are ranked reward for the one at the top, punishment at the bottom. MBO, quotas, incentive pay, business plans, put together separately, division by division, cause further loss, unknown and unknowable." (Senge, p. 2) This statement emphasizes a lack of coordination, collaboration, and commitment across organizations. Consequently an environment not overly conducive to learning prevails. I will explore these elements in greater detail. Brabazon, Matthews, Piranfar, and Tlemsani (2003) argue that: Given an environment of rapid technological change and intense competition, firms continuously seek sustainable sources of competitive advantage: core competences and dynamic capabilities. The ability to learn and adapt is a key feature in this quest, how can these faculties be built into organizational processes and behaviour? The answer that they must be built into organizational routines and architectures is not convincing: they are equally capable of stifling the development of the new. In fact a paradox exists. In a dynamic environment, adaptive capabilities are prized. (p. 1) Furthermore, the theories presented by Charles Darwin some time ago still hold true in this context. Only the strong will survive in the corporate world, these being adaptable, empowered, knowledgeable learning machines that have mastered this critical approach. 2.1 Background Management theory originated during the progressive years of the industrial revolution, and although it has evolved dramatically since this period, we still have so much further to go. The following excerpt provides an overview of how management theory originated: The Classical Management Perspective evolved during the industrial revolution over a century ago as the first recorded management approach in organizational history. The Classical school of thought began

Zink, 6 around 1900 and continued into the 1920s. Traditional or classical management focuses on efficiency and includes bureaucratic, scientific and administrative management. Bureaucratic management relies on a rational set of structuring guidelines, such as rules and procedures, hierarchy, and a clear division of labor. Scientific management focuses on the "one best way" to do a job. Administrative management emphasizes the flow of information in the operation of the organization. (Telecollege, 1998) Traditional organizational structures that originated from the classical framework focused on vertical hierarchies with little communication from the top to the bottom of the structure. Furthermore, the lower-levels contributed very little to organizational strategy and implementation decisions despite having intimate knowledge of the endusers of products. There was little involvement or participation, yet organizations felt that a concentration of power in the executive boardroom was the optimal approach. Or rather, were executives simply threatened by the thought of quality ideas being generated from those deemed to be less significant individuals within the structure? Whatever the case, todays modern business world has changed very little in the past few decades as learning capabilities have been brought to the forefront. Daft (2004) comments: To a great extent, managers and organizations are still imprinted with the hierarchical, bureaucratic approach that arose more than a century ago. Yet the challenges presented by todays environment global competitiveness, diversity, ethical concerns, rapid advances in technology, the rise of e-business, a shift to knowledge and information as organizations most important form of capital, and personal and professional growth call for dramatically different responses from people and organizations. The perspectives of the past do not provide a road map for navigating the world of business today. (p. 26) Organizations at present have failed to address these concerns adequately. How can these challenges be confronted? Initial findings point towards engaging, empowering, mobilizing, and motivating individuals into action. The team dynamic is equally as important. According to Larsen, McInerney, Nyquist, Santos, and Silsbee (1996) those who work in Learning Organizations are fully awakened people. They are relentlessly engaged in their work, striving to reach their full potential, by sharing the vision of a valuable goal with team colleagues. Furthermore, their personal goals are in alignment with the mission of the organization. Larsen et al continue on to declare that: Working in a Learning Organization is far from being a slave to a job that is unsatisfying; rather, it is seeing ones work as part of a whole, a system where there are interrelationships and processes that depend on each other. Consequently, awakened workers take risks in order to learn, and they understand how to seek enduring solutions to problems instead of

Zink, 7 quick fixes. Lifelong commitment to high quality work can result when teams work together to capitalize on the synergy of the continuous group learning for optimal performance. (p. 1) Therefore, employees in Learning Organizations are not slaves at all, but rather they are well prepared for change and working with others. 2.2 Challenges in Todays Environment What are the primary challenges facing todays corporations? The following list offered by Michael Marquardt (1996) highlights the major challenges that all organizations must not only be aware of, but also must manage effectively. If these issues are not addressed adequately, the resulting impacts are potentially perilous. !" Reorganization, restructuring, and reengineering !" Increased skills shortages, with schools unable to adequately prepare for work in the Twenty-first century !" Doubling of knowledge every two to three years !" Global competition from the worlds most powerful companies. !" Overwhelming breakthroughs of new and advanced technologies !" Spiraling need for organizations to adapt to change There are four major areas, which have changed profoundly over the past few years. These too could present challenges for organizations if they are disregarded. According to Marquardt (1996) these are as follows: 1. The Economic, Social and Scientific Environment, which includes globalization, economic and marketing competition, environmental end ecological pressures, new sciences of quantum physics and chaos theory, knowledge and societal turbulence, 2. The Workplace Environment, which includes: information technology and the informated organization, organizational structure and size, total quality management movement (Competitive advantage comes from the continuous, incremental innovation and refinement of a variety of ideas that spread throughout the organization), workforce diversity and mobility, and a boom in temporary help, 3. Customer Expectations, and 4. Workers who thrive will have problem identifier skills, problem solving skills and strategic broker skills. Corporations depend on the specialized knowledge of their employees. Knowledge workers do, in fact, own the means of production and they can take it out of the door with them at any moment. (p. 2) I believe that these potential challenges can be more appropriately tackled in an organization that is adaptive and responsive. 2.3 What is Organizational Learning? There has been increasing focus in recent years on organizational learning for many significant reasons. The rapid advancement of technology, globalization, and accelerating customer expectations in the past decade has brought this concept to the

Zink, 8 forefront both in academia and the business world. Malhotra (1996) offers his perspective for this phenomenon: Among the reasons behind this growth (Dodgson, 1993; Easterby-Smith et al., 1998) is the new characteristics of the business world, together with the extensive analytical value of organizational learning in contributing to the improvement of the understanding of organizations and their activities, are both of great significance. (Easterby-Smith and Araujo, 1999) Argyris (1977) defines organizational learning as the process of "detection and correction of errors." In his view organizations learn through individuals acting as agents for them: "The individuals' learning activities, in turn, are facilitated or inhibited by an ecological system of factors that may be called an organizational learning system". (p. 117) Huber (1991) identifies four distinct areas that are fundamental in the organizational learning process. These are as follows: knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational memory. He clarifies that learning need not be conscious or intentional. Further, learning does not always increase the learner's effectiveness, or even potential effectiveness. Moreover, learning need not result in observable changes in behavior. Taking a behavioral perspective, Huber notes: An entity learns if, through its processing of information, the range of its potential behaviors is changed. (Malhotra, 1996, 2) Weick (1991) assesses the landscape with harsh criticism of learning deficiencies in organizations today. He argues that learning has been largely neglected as of late. His view takes the stance that organizations are not built to learn in their current structures and the resulting impact will be common mistakes repeated from the past. 2.4 What is a "Learning Organization"? How can organizational learning be institutionalized to form a true Learning Organization? According to Malhotra (1996), Peter Senge describes the organization as an organism with the capacity to enhance its capabilities and shape its own future. A Learning Organization is any organization (e.g. school, business, government agency) that understands itself as a complex, organic system that has a vision and purpose. It uses feedback systems and alignment mechanisms to achieve its goals. It values teams and leadership throughout the ranks. ( 4) Michael Marquardt (1996) believes that a systematically defined Learning Organization is an organization, which learns powerfully and collectively and is continually transforming itself to better collect, manage, and use knowledge for corporate success. It empowers people within and outside the company to learn as they work. Organizational learning refers to how organizational learning occurs, the skills and processes of building and utilizing knowledge. (p. 4)

Zink, 9 Peter Senge (1990) characterizes Learning Organizations as businesses in which you cannot not learn because learning is so insinuated into the fabric of life. He proceeds to define Learning Organizations as groups of people continually enhancing their capacity to create what they want to create. Yogesh Malhotra (1996) defines Learning Organizations as "Organizations with ingrained philosophies for anticipating, reacting and responding to change, complexity and uncertainty." (p. 1) He further argues that the concept of a Learning Organization is increasingly relevant given the increasing complexity and uncertainty of the organizational environment. Senge (1990) additionally remarks that the rate at which an organization learns can develop into the paramount sustainable source of competitive advantage for the business. McGill et al. (1992) also propose a definition for the Learning Organization as "a company that can respond to new information by altering the very "programming" by which information is processed and evaluated." (Malhotra, 1996, p. 1) I believe the key is in the word adaptation; the world is ever changing and businesses must stay one step ahead to be competitive and improve their chances of continually realizing sustenance. I believe that a Learning Organization is one in which people at all levels are collectively working to achieve common goals. Learning is the means to achieve this end objective. According to Richard Karash (1994) learning to do is enormously rewarding and personally satisfying. For those of us working in the field, the possibility of a win-win is part of the attraction. That is, the possibility of achieving extraordinary performance together with satisfaction and fulfillment for the individuals involved. ( 3) As witnessed above, Learning Organizations are defined in many differing ways, but a few commonalities exist around teamwork, sharing, empowerment, collaboration, communication and participation. It is irrefutable that these elements are critical to the process. 2.5 Why is a Learning Framework Critical to Organizational Effectiveness? I discussed the challenges facing organizations in the previous section of this study, those of which provide a persuasive enough argument that supports why learning is crucial. Learning today is undoubtedly a non-negotiable. The following quote from Peter Senge (1990) emphasizes why a relentless pursuit of learning excellence is so important to organizational success. If anything, the need for understanding how organizations learn and accelerating that learning is greater today than ever before. The old days when a Henry Ford, Alfred Sloan, or Tom Watson learned for the organization are gone. In an increasingly dynamic, interdependent, and unpredictable world, it is simply no longer possible for anyone to figure it all out at the top. The old model, the top thinks and the local acts, must now give way to integrating thinking and acting at all levels. While the challenge is great, so is the potential payoff. The person who figures out how to harness the collective genius of the people in his or her

Zink, 10 organization, according to former Citibank CEO Walter Wriston, is going to blow the competition away. (p. 10) According to Richard Karash (1994), Learning Organizations drive collaborative atmospheres like no other type of organizational approach. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, they involve simply doing the right thing. Karash comments, it seems possible that the Learning Organization can bring into our enterprise institutions the possibility of systems thinking in action, and shorten the feedback loops so that collective action for the general welfare is not just possible, but expected. Thus the Learning Organization, unlike other technologies for business, is not about the bottom line first. It is about living with paradox and choosing life-affirming values. ( 35) By extrapolating and adding to Karashs point, it becomes clear that doing the right thing, by putting values first, will augment business results in the long-term as customers realize that a responsible, accountable, and winning strategy is in play. Therefore, learning frameworks are not only a business imperative, they are also a winning proposition in every sense. Art Kleiner (1996) offers the view that current business perspectives have failed to evolve with the changing times; Because we need a different way of viewing the process of conducting activity in a business environment and of achieving change within that environment. Our existing views and ways of understanding are not keeping up with the realities of that environment nor with our own belief system, which defines that environment. ( 5) Kleiner provides the following list highlighting the critical reasons why organizations must relentlessly adapt and learn: !" To realize superior performance and competitive advantage !" For customer relations !" To avoid decline !" To improve quality !" To understand risks and diversity more deeply !" For innovation !" For our personal and spiritual well being !" To increase our ability to manage change !" For understanding !" For energized committed work force !" To expand boundaries

Zink, 11 !" To engage in community !" For independence and liberty !" For awareness of the critical nature of interdependence !" Because the times demand it Karash (1994) provides additional reasons for creating Learning Organization structures. These include giving people hope, increasing satisfaction in the workplace, generating creativity and idea sharing, leveling vertical hierarchies, and augmenting participation. I think another driver towards organizational learning is change. It's been said frequently but the greatest constant of modern time is change. With regards to the organizations we are in, change consistently challenges traditional institutional practices and beliefs. As accelerated change drivers intensify in the years ahead it will be all the more urgent to be responsive and adaptable. (Karash, 1994) A structured system approach to change dynamics will ensure that organizations are adequately prepared for what will come next. Forward thinking and learning from previous experiences are also significant aspects of this new evolution. The Optimized Learning Model (OLM) discussed in this study highlights these two necessities in further detail. Commitment is a key in the learning process, as individuals must feel that they can truly have impact and make a difference. Once it is perceived that all team members are vital in the process it will begin to be institutionalized. Karash (1994) supports this view, Where I am becomes a Learning Organization the moment I perceive it to be one, as I share insights with others. It is born with the discovery that together we can contribute to evolution, that not knowing how to stretch together we can each learn how. ( 18) The concept of unity shines through. The team aspect behind Learning Organizations is significant in every respect. Karash (1994) proceeds to contrast organizational behaviour in non-learning and learning environments. The old way is for senior managers to do all the thinking while everyone else "wields the screwdrivers". The old way works, but doesn't tap the greater energy available when the team is fully engaged. Tapping into this energy can result in improved products and services for customers, and an improved work environment. The Learning Organization approach is a new way that promises to tap into this energy. Any approach that increases joy in work and the quality of products and services raises the overall quality of life. I'm only interested in Learning Organizations insofar as they: (1) Provide people with more satisfying lives, so they are happier, do more interesting things with their lives, and are more fun to have lunch with; and (2) Promote systems thinking enough so we have a snowball's chance in hell of restoring enough sanity to our motives so we don't fall into any of the "Limits to Growth" scenarios during my lifetime. (Or

Zink, 12 hopefully many centuries to come, though knowing the collapse may well come while I'm around lends a bit more urgency.) ( 23) Karash goes on to extrapolate the benefits of Learning Organizations forward to economic returns. It is clearly evident that doing the right thing ethically and morally can bring colossal gains within the economy as well. Because I believe that there is a new level of efficiency and effectiveness to be gained in organizations that master the intricacies of the Learning Organization. I think it is the next level of evolution for organizations and I'd like to help my company and mankind to get there. (Karash, 1994, 28) Why do we want Learning Organizations? Shoshana Zuboff (2004) has written: The behaviours that define learning and the behaviours that define being productive are one and the same. Learning is the heart of productive activity. To put it simply, learning is the new form of labour. (q. Marquardt, 1996, p. 2) Karash (1994) expands on this view by providing a broad overview for why learning is so critical. He pronounces: We want to live "divided no more." We want work and personal goals to be in sync or chosen for legitimate reasons. We want to instill greater levels of personal commitment and creativity in the work force. We want to have our work and our organization work be in harmony not at odds. We want to be able to produce exceptional business results in an ever-changing environment. ( 48) Integration is extremely important in the argument for learning frameworks. I feel strongly that Karash has made a significant point in this respect. The personal gains mentioned above will drive the business forward in every sense. The cart (bottom line results) should never be put ahead of the horse (personal and team gains) again. So why do we want to establish a Learning Organization? Karash (1994) believes that such an environment is essential to the continued growth and development of organizations. He also imagines that work should not be an obligation but a joy and that learning and creativity drive the future. Karash then declares, without Learning Organizations we will not be able to transition into the next millennium and meet the challenges ahead. ( 50) Meeting lofty corporate goals and expectations is dependent upon this successful transformation he argues. In conclusion we need Learning Organizations primarily because they provide the healthiest kind of environment for human beings to be in. Secondarily, they improve the bottom line effectiveness of organizations; this effectiveness is achieved through continuous learning resulting in continuous improvement. Dr. Eileen Pepler (2006) coined the phrase tell me and Ill forget, show me and I may remember, involve me and Ill truly understand. This saying resonates with me and provides further credence behind Learning Organization ideology.

Zink, 13 2.6 Barriers to Learning Organizations What stops us from learning and implementing learning cultures within our organizations? Karash (1994) outlines some of these barriers as follows: !" Defensive routines !" Dynamic complexity of systems !" Inadequate and ambiguous outcome feedback !" Misperceptions of the feedback !" Poor interpersonal and organizational inquiry skills Defensive routines generally imply complacency, complex systems are intimidating, a lack of concrete feedback means that inaccurate decisions often result, and communication gaps are perhaps the most deadly of all. These obstacles are not easy to overcome from an organizational perspective. If we could collectively see and to some extent overcome these barriers, the environment, our families, our communities and our organizations would all dramatically improve, thus another reason for pursuing organizational learning. We need to take the holistic view. I believe that the greatest impediment to driving a learning framework is fear of the unknown, which ultimately results in complacency. Many organizations fail to buy-in to this modern ideology for the reasons outlined above by Karash. As more businesses achieve large-scale wins in the near future the importance of learning will once again be front and center. The following section of this paper identifies the key issues prevalent and the resulting study purpose.

3.0 Overview of the Issues and Study Purpose

According to Fortune magazine (Domain, 1989), "the most successful corporation will be something called a Learning Organization, a consummately adaptive enterprise." (p. 48-62) Businesses must evolve with the changes in society. They must keep up with technological, customer-focused, and globalization trends. Responsiveness is key. So why do so many organizations resist this critical transformation in favour of traditional vertical structures that are largely ineffective in todays business world? Richard Karash (1994) views many of the existing organizational forms and processes as machinelike, where humans are seen as parts of the machine, and not only in traditional bureaucracies either. This error in management perception and approach is dangerous in any economy where human input is deemed to be merely another commodity in the production process. Mark Smith (2001) interprets the issue as nearsightedness on the part of organizations who fail to take the long-term view. Simply put organizations fail to see

Zink, 14 the true benefits of learning frameworks because they are shortsighted, focused on simply satisfying near-term goals and metrics. A failure to attend to the learning of groups and individuals in the organization spells disaster in this context. Leadbeater (2000) has argued, companies need to invest not just in new machinery to make production more efficient, but also in the flow of know-how that will sustain their businesses. Organizations need to be good at knowledge generation, appropriation and exploitation. ( 14) In 1990 Peter Senge, the father of modern Learning Organizational theory, introduced new concepts and strategies for driving continuous learning frameworks within organizations. While his theories provided great substance in this area of management theory, issues were also brought to the forefront. These include a failure to fully appreciate and incorporate the imperatives that animate modern organizations; the relative sophistication of the thinking he requires of managers and questions around his treatment of organizational politics. It is certainly difficult to find real-life examples of Learning Organizations (Kerka, 1995). There has also clearly been a lack of critical analysis of the theoretical framework. (Smith, 2001) Finger and Brand (1999) bring attention to the following Learning Organization shortcomings: The concept of the Learning Organization: 1. Focuses mainly on the cultural dimension, and does not adequately take into account the other dimensions of an organization. To transform an organization it is necessary to attend to structures and the organization of work as well as the culture and processes. Focusing exclusively on training activities in order to foster learning favours this purely cultural bias. 2. Favours individual and collective learning processes at all levels of the organization, but does not connect them properly to the organizations strategic objectives. Popular models of organizational learning (such as Dixon 1994) assume such a link. It is, therefore, imperative, that the link between individual and collective learning and the organizations strategic objectives is made. And 3. Remains rather vague. The exact functions of organizational learning need to be more clearly defined. (p. 146) These shortcomings, Finger and Brand argue, make a case for some form of measurement of organizational learning, so that it is possible to assess the extent to which such learning contributes or not towards strategic objectives. (Karash, 1994) Also, I completely agree that learning objectives must be in sync with strategic objectives. We must be working towards common goals to be effective. There are a number of flaws in Senges model, and the subsequent models that have followed, according to the research uncovered in this study. Chiefly they are theoretically underpowered and there is some question as to whether they can be brought into practice effectively. These implementation questions are particularly concerning. It seems likely that these opinions and models continue to be treated as the

Zink, 15 prototypical answers to organizational problems, but in reality none of which has the legs to meet these visions in isolation. (Smith, 2001) In summation, a severe, and potentially perilous, learning deficiency exists at present in the business world. This critical concern stems from the actuality that a viable holistic learning framework is nonexistent for leadership teams to embrace. Consequently, the following objective of this study has been born. To develop a macro strategic and executable framework capable of launching learning excellence within organizations across the corporate world. This objective effectively addresses both the theoretical and practical deficiencies currently prevailing in the business world. The organizational shortcomings mentioned in this section of the study clearly act as obstacles when organizational leaders are deciding whether to take up a learning structure and mentality. As a result, the following section of this study will analyse learning frameworks in a manner that addresses the issues here within.

4.0 Why Teams Trump Individuals in the 21st Century

4.1 Uniform Qualities within Effective Teams Authors French and Bell (1995) consider teams and work groups to be the fundamental units of organizations and the key leverage points for improving the functioning of the organization. (p. 171) Teams and teamwork are the hottest thing happening in organizations today (p. 97) A workplace team is more than a work group, a number of persons, usually reporting to a common superior and having some face-toface interaction, who have some degree of interdependence in carrying out tasks for the purpose of achieving organizational goals. (p. 169) Teams are a fundamental aspect of Learning Organizations, as individuals work together and learn from all of their shared experiences. A number of writers have studied teams, looking for the characteristics that make some successful. Larson and LaFasto (1989) looked at high-performance groups as diverse as a championship football team and a heart transplant team and found eight characteristics that are always present. They are listed below: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. A clear, elevating goal A results driven structure Competent team members Unified commitment A collaborative climate Standards of excellence External support and recognition Principled leadership

Zink, 16 (Larson and LaFasto, 1989, in French and Bell, 1995, p. 98) This list covers the key areas enclosed in this study teamwork, leadership support, commitment, communication, and collaboration. Lippett (1982, p. 9) maintains that high-performance teams operate on four distinct levels, which includes: organizational expectations, group tasks, group maintenance, and individual needs. Lippett goes on to define teamwork as the means by which a group is able to solve its problems. Teamwork is demonstrated in groups by: (a)...the groups ability to examine its process to constantly improve itself as a team, and (b) the requirement for trust and openness in communication and relationships. Group interaction, interpersonal relations, group goals, and communication characterize the former. The latter is characterized by a high tolerance for differing opinions and personalities. (Lippett, 1982, p. 207-208; Larsen et al, 1996) Therefore, it is strikingly evident that teams are a central importance behind organizational success. 4.2 Shared Vision Within Teams Shared visions must be built from the individual visions of an organizations members. This implies that organizational visions must not be created by the leader; rather, the vision must be created through interaction with the individuals in the organization. In LOs the key is in participation and involvement. According to Larsen et al (1996), Only by compromising between the individual visions and the development of these visions in a common direction can the shared vision be created. The leader's role in creating a shared vision is to share their own vision with employees. This should not be done to force that vision on others, but rather to encourage others to share their vision too. Based on these visions, the organization's vision should evolve. (p. 6) In my opinion this is one area that requires attention by senior management teams across the globe. Often they push a vision through the organizational framework without gaining support through mutual contributions. Larsen et al (1996) believe that it would be naive to expect that the organization can change overnight from having a vision that is communicated from the top to an organization where the vision evolves from the visions of all the people in the organization. (p. 6) The collective view is paramount in the context of creating support and commitment. Larson et al (1996) investigated the question of whether all individuals within a Learning Organization must share a common vision. They wrote, reflection on shared vision brings the question of whether each individual in the organization must share the rest of the organization's vision. The answer is no, but the individuals who do not share the vision might not contribute as much to the organization. (p. 5) Senge (1990) stresses that visions cannot be sold. For a shared vision to develop, members of the organization must enroll in the vision. The difference between these two is that through enrollment the members of the organization choose to participate. Learning Organization achievement can only be realized in a true sense when a shared vision with full, unwavering commitment is prevalent. The team element within

Zink, 17 this context is also so important. Individuals must truly be committed to a team-based vision for the business moving forward. Leadership plays a key role in establishing this guidance, which will be discussed next.

5.0 Leadership and Driving Learning Distinction

Our traditional view of leaders, as special people who set the direction, make the key decisions, and energize the troops, is deeply rooted in an individualistic and nonsystemic world-view. In a Learning Organization, leaders' roles differ dramatically from that of the charismatic decision maker. Leaders are designers, teachers, and stewards. These roles require new skills: the ability to build shared vision, to bring to the surface and challenge prevailing mental models, and to foster more systemic patterns of thinking. In short, leaders in Learning Organizations are responsible for building organizations where people are continually expanding their capabilities to shape their future, that is, leaders are responsible for learning. (Senge, 1990) According to Senge (1990), it is fruitless to be the leader in an organization that is poorly designed. The first task of organizational design concerns designing the governing ideas of purpose, vision, and core values by which people will live. Few acts of leadership have more enduring impact on an organization than building a foundation of purpose and core values. The second design task involves the policies, strategies, and structures that translate guiding ideas into business decisions. Behind appropriate policies, strategies, and structures are effective learning processes; their creation is the third key design responsibility in Learning Organizations. Senge remarks: Leader as teacher does not mean leader as authoritarian expert whose job is to teach people the "correct" view of reality. Rather, it is about helping everyone in the organization, oneself included, to gain more insightful views of current reality. The role of leader as teacher starts with bringing to the surface people's mental models of important issues. These mental pictures of how the world works have a significant influence on how we perceive problems and opportunities, identify courses of action, and make choices. (p. 6) In Learning Organizations, this teaching role is developed further by virtue of explicit attention to mental models and by the influence of the systems perspective. Leaders as teachers help people restructure their views of reality to see beyond the superficial conditions and events into the underlying causes of problems, and therefore to see new possibilities for shaping the future. Specifically, leaders can influence people to view reality at three distinct levels: events, patterns of behavior, and systemic structure. (Senge, 1990) According to Senge (1990), contemporary society focuses predominantly on events, less so in patterns of behavior, and very rarely on systemic structure. Leaders in Learning Organizations must reverse this trend, and focus their organization's attention on systemic structure. This is because event explanations, who did what to whom, doom their holders to a reactive stance toward change; pattern-of-behavior explanations

Zink, 18 are limited to identifying long-term trends and assessing their implications, they suggest how, over time, we can respond to shifting conditions (adaptive learning). The structural explanations are the most powerful, only they address the underlying causes of behavior at a level such that patterns of behavior can be changed (generative learning). Leaders engaged in building Learning Organizations naturally feel part of a larger purpose that goes beyond their organization. They are part of changing the way businesses operate, not from a vague philanthropic urge, but from a conviction that their efforts will produce more productive organizations, capable of achieving higher levels of organizational success and personal satisfaction than more traditional organizations. (Senge, 1990) Introducing a Chief Learning Officer role within an organization is also a significant move in recognizing and rewarding learning initiatives. This champion will oversee all learning within the structure. Organizational leaders, such as CEOs and Presidents should not overlook the importance of this guiding role. Walker (1998) provides more perspective: Learning organizations use shared leadership principles to maximize their resources and develop leadership capacity within individuals. The organization can be described as one that learns continuously and transforms itself. Current literature on leadership development characterizes the leader as a coach, facilitator and guide. Images of leadership have shifted from expert, director, and controller to catalyst, information sharer, and coordinator. Leadership in learning organizations is based on cooperative and collaborative partnership approaches. (p. 1) Senges (1990) view, in that Learning Organization leaders are designers, stewards and teachers, is a valid one. Leaders are responsible for building organizations where people continually expand their capabilities to understand complexity, clarify vision, and improve shared mental models; in essence they are responsible for learning. Learning Organizations will remain a good idea, until people take a stand for building such organizations. Taking this stand is the first leadership act, the start of inspiring (literally to breathe life into) the vision of the Learning Organization. Bringing this visionary and ideological model to life is the most powerful, and rewarding, move any executive team can undertake. (p. 340)

6.0 Gaining Commitment

Kofman & Senge (1995) have stated that building Learning Organizations requires basic shifts in how we think and interact. They go on to argue that the main issues in today's organizations are actually the consequences of their success in the past. These dysfunctions, therefore, are not problems to be solved; they are frozen patterns of thought to be dissolved. The solvent they propose is a new way of thinking, feeling and being: a culture of "systems." In this new systems world-view, we move from the primacy of pieces to the primacy of the whole, from absolute truths to coherent interpretations, from self to community, from problem solving to creating. Thus, by

Zink, 19 commitment, they mean "commitment to changes needed in the larger world and to seeing our organizations as vehicles for bringing about such changes." (Santos, 2006, 7) The position stated above by Santos regarding Kofman and Senge is a valid one. Organizational leaders, from a top-down perspective, must understand the impact that they can have. Commitment is a key when any change management initiative is undertaken. Support from above will enable a trickle down effect through the structure within a business; this point cannot be lost with senior management. Thus, the effectual communication of corporate commitment is as vital as having commitment period. (Kofman et al, 1995) The approach adopted by MIT's Organizational Learning Center, when the Center gets involved with organizations that desire to become Learning Organizations, states that the members of such organizations should be committed to a "galilean shift" of mind, and explains what that means in terms of changes in individual values and organizational culture. (Santos, 2006) Commitment is therefore paramount in the decision to take up a Learning Organization. Aldo Santos (2006) adds context to this assertion: In Learning Organizations, the leaders are those building the new organization and its capabilities. Such leadership is inevitably collective. The clash of collective leadership and hierarchical leadership nonetheless poses a core dilemma for Learning Organizations. The dilemma can become a source of energy and imagination through the idea of "servant leadership," people who lead because they chose to serve, both to serve one another and to serve a higher purpose. ( 28) Santos continues on by positioning Learning Organizations as being anchored in three foundations: (1) a culture based on transcendent human values of love, wonder, humility, and compassion; (2) a set of practices for generative conversation and coordinated action; and (3) a capacity to see and work with the flow of life as a system. He believes that as a resulting impact of these capabilities, Learning Organizations are both more generative and more adaptive than traditional organizations. This is due to their commitment, openness, and ability to deal with difficulties. Employees, in his view, find security not in stability but in a dynamic equilibrium realized in an environment of constant change. (Santos, 2006) When defining commitment the question persists, commitment to what? Employees must be committed to openness and communication in a participatory atmosphere. Furthermore, positive feedback is critical when individuals or groups take risks to improve the business. It also involves communication that flows as much from the bottom of a hierarchy to the top as vice-versa. Inquiry allows individuals to become adept at questioning things as a normal course of their work. It encourages people to take risks in improving aspects of their work. Positive feedback involves activities that are designed to let people learn from their inquiries, to build a personal knowledge base

Zink, 20 that is defined by proactive rather than reactive or defensive thinking. It involves those with more experience helping those with less experience understand not just the right way to do things, but what can be learned from doing things the wrong way. The key elements are communication, reflection, feedback, flexibility, and inquiry. Mutual respect and support are also significant pieces. This involves treating co-workers, supervisors, and employees uniformly with respect to one's ability to contribute positively to the organization, regardless of where that person is located in the organizational hierarchy. The ultimate answer to the question becomes commitment to a cultural shift that incorporates all of these critical aspects. (Albany Education, n.d.) Consequently gaining commitment is as straightforward as driving a corporate culture that empowers, involves, engages, and encourages action and participation in a team-oriented setting. It must be also noted that the entire organization from the boardroom to the trenches has to believe, adamantly buying-in and supporting the entire system.

7.0 Culture and the Learning Organization

A positive relationship exists between strong culture and LO effectiveness. Daft (2004) provides a worthy opinion in respect to culture: One of the primary characteristics of a Learning Organization is a strong organizational culture. In addition, the culture of a Learning Organization encourages change and adaptation. A danger for many successful organizations is that the culture becomes set and the company fails to adapt as the environment changes. When organizations are successful, the values, ideas, and practices that helped attain success become institutionalized. As the environment changes, these values may become detrimental to future performance. Many organizations become victims of their own success, clinging to outmoded and even destructive values and behaviors. (p. 371) According to Daft, one of the defining characteristics of Learning Organizations is a strong adaptive culture that incorporates the following values: 1.The whole is more important that the parts and the boundaries between the parts are minimized, 2. Equality and trust are primary values, and 3.The culture encourages risk taking, change, and improvement. The culture of a Learning Organization encourages openness, reduced boundaries, equality, empowerment, continuous improvement, and risk taking. Adaptive cultures allow organizations to respond to internal and external pressures in an efficient manner. Employees of all ranks, due in large part to this level of responsiveness, embrace change because they know that they have the ability to be creative and bring conceptual theory to practice. The ability to know that you can make things happen is extremely valuable from a motivational perspective. (Daft, 2004, p. 372)

Zink, 21 Other key aspects of an adaptive learning culture are perpetual communication and collaboration through teamwork. Information and knowledge exchange must be shared through all areas of the organization. By instilling an open, team-oriented culture a sense of family or community will be born. This will reduce barriers in respect to communication, encourage collaboration, and support a Learning Organization framework. (Daft, 2004, p. 372)

8.0 The Birth of a New Learning Model - OLM

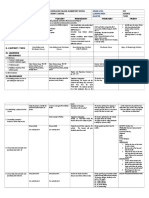

As stated previously in this study, creating a learning culture and structure is a long-term effort contingent on continuous improvement that must be supported at all levels of the organization. Organizational Development, from structure and strategy all the way down to individual processes, will be improved through an enhanced learning framework that incorporates the critical ingredients mentioned in the previous section of this paper. (Larsen et al, 1996) After completing a great deal of research for this paper, I have constructed a learning model, termed Optimized Learning Model (OLM), to support organizations in driving learning excellence during organizational formation and development and beyond. This model is unique in the sense that strategy and structure are finally being integrated with learning excellence into a complete model for application. Learning, from overall structural design, the identification of certain departments, individual roles and relationships, the formation of teams, and the use of certain communication, to information and systems, will be analysed comprehensively in the new framework. OLM is the product of the research discussed in the analysis portion of this study. It addresses organizational needs in respect to culture, information sharing and flow, leadership, team fundamentals, and commitment. Section 8.2 initiates a thorough analysis of the model in respect to how it consolidates and builds on these elements. Subsequently, the theories of Peter Senge, Nick Bontis, Popper & Lipshitz, Robert Flood, and David Cayla are reviewed and critically investigated to illustrate linkages and contrasts to OLM. Hence presumably providing further support for the new approach. It must be noted that all of these works individually and in isolation fall short of fully integrating a learning model capable of immediate implementation in the business world. Furthermore the framework is explored in isolation to uncover its internal shortcomings and benefits as well. Section 8.1 provides an illustration of the new OLM model.

Zink, 22 8.1 A Model For Learning Excellence - OLM

Optimized Learning Model

Leadership

CEO

Ongoing Communication

Learning

CLO

Organizational Strategy

Functional Areas Management Team

Learning Strategy

Continuous Improvement Team

Learning Team

(4Is)

Project Management

Definition Clarity Structure Support

Multi-Faceted Teams

Empowerment Collaboration Communication Trust Adaptability Autonomy Experimentation Diversity

Project Fulfillment

Performance Results

Learning Results

Outcomes

Zink, 23 8.2 Examining the Model OLMs Functionality OLM, as illustrated above, is a dynamic, pervasive model that focuses on the flow of knowledge through an organizational structure. It further draws distinct responsibilities for the organizational parts of the structure. Specifically, two critical elements are recognized. These are Leadership and Learning. A third element, distinctive but entirely influenced by Leadership and Learning, is the Project Management aspect that physically puts strategy into action. We are finally beginning to recognize that vitalizing the relationships between the parts of the system is of greater consequence than optimizing the parts of the system. (Crother-Laurin, 2006, p. 5) Therefore, it is critical for efficient and effective interaction among these moving parts. These three elements will be investigated further in isolation and jointly as they apply to the model. 8.2.1 Leadership Fostering an environment that is supportive of learning is no easy feat. Leadership teams are responsible for setting this stage before any steps are taken to implement learning strategies. Further, ensuring that a corporate culture shift has transpired is also essential. Additionally, Leadership teams are responsible for bonding collective learning processes with the vision, mission, and strategic objectives of the firm. This implies that a genuine and enduring commitment to learning is necessary for effectiveness within OLM. Leadership teams are accountable for ensuring that individuals are in a position to embrace learning cultures. This is extremely vital to the success of effectively driving learning excellence. Crother-Laurin (2006) believes that it is clear that organizational transformation does not begin with management providing or mandating opportunities for collaboration or teamwork. It begins with each individual, and therefore, is the responsibility of the leaders to foster each individuals learning and development such that collectively the organization can realize the capacity and contribution of each member. Compensation is also a key in the new OLM framework from a leadership perspective. Team-based incentive pay will be employed as a primary motivator to enhance group cohesion. In order to improve idea generation and knowledge sharing, bonuses will be paid to individuals that take risks and drive results. This approach will deviate from individual recognition programs that encourage personal rather than teambased activities, which ultimately contrasts the basis behind learning environments. Shared knowledge is best achieved where group rewards drive information exchanges throughout the organization. Leadership teams must design compensation models that are consistent with this imperative methodology. In the context of OLM formalized rules must be limited to allow individuals and teams to have free reign to generate ideas, share knowledge, and collaborate. Nonetheless formal rules are still required to provide a certain level of structure in respect to procedures. They will mostly govern the proceedings that occur within the project component of the structure where the operational aspect of the business

Zink, 24 persists. The Learning team is responsible for ensuring that formal and informal rules do not act contrary to the learning capabilities of the organization. How should business leaders assess progress in a Learning Organization? Traditionally organizations have used financial results as the primary measure of success. In the context of OLM, I recommend that the true measure of progress be held in the level of learning generated from within. Team gains, through cross-functional project returns, are a further measure of success. A collective view of project effectiveness will determine the success of the organization regardless of the financials. The quantity and quality of ideas flowing through the structure are the means to achieve the desired end in our rapidly evolving business world. 8.2.2 Learning OLMs success, at a high-level, hinges on organizations releasing the restraints on learning, which ultimately unleashes its full capability. Bingham (2006) comments, organizations need to quantifiably understand the impact of learning on their respective businesses. Driving that understanding is the responsibility of learning professionals. (p. 15) The Learning Division must have complete and absolute autonomy within the structure. Although the CLO (Chief Learning Officer) will report directly into the CEO, the CEO will remain hands-off from the day-to-day operations of the learning function. Ultimately this autonomy will promote an unbiased long-term approach to learning. Communication between the two groups is also important as Learning must understand corporate strategy and Leadership must be aware of the knowledge coming out of the learning system. OLM will encourage this positive relationship. All information within the organizational structure will flow into the Learning Department at one point or another. Projects will define the work that is required to be completed within OLM. This ranges from fulfilling client orders to change management tactics, and everything there in between. The most important aspect of the system is the constant and relentless flow of information. Alcorta (2005) defines feedback loops as cycles of interaction within and between organizations. He believes that they emerge in the chain-linked model of innovation between downstream and upstream phases of the firm, including short-loops linking each downstream phase, which defines knowledge infrastructure as the range of generic, multi-user, divisible and enabling organizations supporting the production of knowledge. The central chain with the phase immediately preceding it, e.g. marketing and production, and longer feedback loops linking extreme phases, i.e. research with marketing. They also emerge between organizations. (p. 21) Lundvall (1992, 1994) argues that responsive feedback loops between individuals and teams can allow the organization to obtain updated and precise information when demands and competencies evolve. Metcalfe (1997) points to the role of formal links and feedback loops that progressively accelerate the connectivity between organizations and, as a result, lead into learning from each other. Therefore, the use of feedback loops, in enhancing internal and external organizational communication, is clearly paramount.

Zink, 25 Leadership and Learning elements will help to shape the undertakings of the project function. More specifically, Leadership will define and convey strategic initiatives while Learning focuses the project world on continuous improvement through experience and collaborative efforts. As information pours into the Learning Department it will be stored, interpreted, analysed, and disseminated. This evolution from data to knowledge is significant in the structure. All the more important however, is the distribution and accessibility of such. Knowledge storage and retrieval is a responsibility of the Learning Department through the use of a database system, intranet, and mass email system. Every employee will be included in the system, regardless of his or her position within the company. This approach will enhance commitment, through active involvement, as feedback loops will exist in all directions. Of principal importance is the constant flow of information with a sense of urgency universally. Further, the analysts within the learning area are accountable for interpretation and analysis of all information that flows into their department. Making heads or tails of this data, in an effort to transform it into knowledge and intelligence, is critical to success. Moreover, a determination on the importance or priority of information is also a key to success, as is the speed of transference achieved. The organizations that best accomplish this mandate will have a competitive advantage against their competitors. Mentorship is another critical element within the learning function. Senior employees will meet with groups of junior employees to convey their knowledge and skills, thus encouraging learning in an open environment. (George-Leary, p. 29) The Learning function will oversee this process for the various areas within the structure. Of primary importance here is to enhance the quality of knowledge and capability in the three key areas of the organization (Learning, Leadership, and Project Management) through mentorship tactics. The essence of OLM is not just focused on informational flows but teamwork and collaboration in this innovative horizontal structure. The Learning Department is also responsible for encouraging information exchange through collaboration and teamwork excellence. Therefore it is critical that the Learning function be given the full autonomy to drive this outcome. 8.2.3 Project Management Project Management is at the heart of the new structure because project performance is the means by which a major component of the work within a business is achieved. This includes everything from completing client orders to distribution logistics to marketing a new line of products to inventory counting. Projects enable us to adapt to changing conditions. (Verzuh, 1999, p.10) Given the rapid change evolution that the world is currently witnessing, it is clear that project success is critical in staying ahead of the curve. For clarity, it must be noted that the term Project Management in the context of this study is used universally to reflect the means by which any organization

Zink, 26 undertakes fulfilling strategy and objectives. However, in my opinion a formalized Project Management element is nonetheless the optimal approach for all organizations. Project management success hinges on consistency and transparency. In order to achieve standardization, the project office staff will develop a custom learning development project management methodology that blends the best practices of project management with instructional systems design. The team will focus on identifying strengths and weaknesses in project management processes, establishing a project management capability baseline, setting up a continuous improvement program, and integrating effective project management principles. (George-Leary, p. 30) Fundamentally project outcomes power businesses forward, or conversely, will set them back. Therefore, it is vital to learn from successes and failures that stem from project initiatives. This said, feedback loops must remain open with uninterrupted information flowing into the Learning Department. Collection, analysis, interpretation, dissemination, and storage and retrieval are the next significant elements in the system, the responsibility of Learning champions. The Project Management group, in so many ways, will therefore constantly evolve from this continuous improvement process. In summation, learning is driven through the structure from project initiation to fulfillment to feedback loops back to the learning center. OLM, from a strategic perspective, delivers a model to business leaders that will combat the challenge of driving learning excellence within their boundaries. Learning effectiveness in the modern business age will allow organizations to remain competitive as they confront globalization, technology, and customer threats and opportunities that they have never witnessed before. 8.3 OLMs Contributions and Shortfalls OLM delivers a number of significant contributions and shortfalls. I will first compare this new model to a list of essential LO dimensions from Marquardt (1996) to assess whether these necessities are existent. Marquardts dimensions are as follows: !" Learning is accomplished by the organization system as a whole !" Organization members recognize the importance of ongoing organization-wide learning !" Learning is a continuous, strategically used process integrated with and running parallel to work !" There is a focus on creativity and generative learning !" Systems thinking is fundamental !" People have continuous access to information and data resources

Zink, 27 !" A corporate climate exists that encourages, rewards, and accelerates individual and group learning !" Workers network inside and outside the organization !" Change is embraced, and surprises and even failures are viewed as opportunities to learn !" It is agile and flexible !" Everyone is driven by a desire for quality and continuous improvement !" Activities are characterized by aspiration, reflection, and conceptualization !" There are well-developed core competencies that serve as a taking-off point for new products and services !" It possesses the ability to continuously adapt, renew, and revitalize itself in response to the changing environment The OLM is uniform to Marquardts dimensions. It delivers systematic thinking with dynamic flow from one team to the next. The structure is established as multifaceted teams that work to achieve project success. Moreover, feedback loops are continually streaming into the Learning Department where gathering, consolidation, analysis, dissemination, and storage are undertaken. Learning of all types are fostered and embraced no knowledge is too trivial in this model. Commitment is realized through involvement, empowerment, and recognition. Employees at all levels are encouraged and rewarded for thinking outside of the box. They are challenged to introduce knowledge that the Learning Department has yet to experience, positive rewards for such will result. Furthermore, risk taking will not be penalized in this model, but risks must be team plays to ensure that a multitude of cross-functional specialists have been employed. In Marquardts words failures are all opportunities to learn. (p. 4) Moreover, the framework is based on the belief that Project Management success is best achieved in a system of continual and relentless learning. Project Management is therefore seen as a key element in OLM as the means to achieve the end it is the implementation arm of the framework for putting strategy into action. The contributions of OLM are numerous, many of which have been discussed previously in this study. Fundamentally this model introduces a framework that business leaders can utilize to improve their organizations chances of survival in our fast paced world. OLM links Learning and Leadership with Project Management into a framework with free information exchange and flow. The benefits of these characteristics are extensive and powerful in and of themselves.

Zink, 28 The shortcomings of OLM are as follows: !" The model is untested in a practical sense !" Total Leadership commitment is essential to success !" The model is not modular parts are all linked together !" The model calls for sweeping changes in most cases to culture, organizational structure, and processes which may question its feasibility OLM, like all other theoretical models, comes with a host of question marks in combination with so many positives. Notably, it is a model that will deliver great benefits for organizations that are committed to a long-term framework for success. Thus, shortterm oriented organizations need not apply. The following sections of this study investigate OLM versus a whole host of leading theoretical approaches from some of the great thinkers of our day. 8.4 Senge Overview and Comparison to OLM Peter Senge is deeply influential in the organizational learning arena. His theoretical work around Learning Organizations has single handedly reshaped organizational behaviour in the past few decades. According to Senge (1990), Learning Organizations possess the capability to: !" Anticipate and adapt more readily to environmental impacts !" Accelerate the development of new products, processes, and services !" Become more proficient at learning from competitors and collaborators !" Expedite the transfer of knowledge from one part of the organization to another !" Learn more effectively from its mistakes !" Make greater organizational use of employees at all levels of the organization. !" Shorten the time required to implement strategic changes !" Stimulate continuous improvement in all areas of the organization The following section addresses the aspects that Senge sees as paramount in learning structures. 8.4.1 Realizing Senges Five Disciplines Peter Senge (1990) defines Learning Organizations as organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set

Zink, 29 free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together. Senge frames our understanding of the Learning Organization with an ensemble of disciplines, which he believes must converge to form a Learning Organization. (Heathfield, 2006) Senge's Learning Action Model creates a disciplined system that provides a logical map to guide strategists through a process that produces real results and continuous learning. The model assists to recognize where you are now in any given process, suggests what to do when you're there, and what to do next. (Shibley, 2001) Senge identifies five key areas for his theory, which are discussed next. Personal Mastery Personal mastery is the discipline of continually clarifying and deepening our personal vision, of focusing our energies, of developing patience, and of seeing reality objectively. (Senge, 1990, p. 7) Senge proposes that an organizations learning is only as effective as that of each of its individual members. Consequently, personal mastery and the desire for continuous learning integrated deeply in the belief system of each person is critical for competitive advantage in the future. (Heathfield, 2006) Senge (1990) provides further context into personal mastery by proclaiming that people with a high level of personal mastery live in a continual learning mode. They never arrive. Sometimes, language, such as the term personal mastery creates a misleading sense of definiteness, of black and white. But personal mastery is not something you possess. It is a process. It is a lifelong discipline. People with a high level of personal mastery are acutely aware of their ignorance, their incompetence, their growth areas. And they are deeply self-confident. Paradoxical? Only for those who do not see the journey is the reward. (p. 142) Mental Models Heathfield (2006) defines mental models as deeply held pictures that each of us holds in our mind about how the world, work, our families, and so on work. Mental models influence our vision of how things happen at work, why things happen at work, and what we are able to do about them. Moving the organization in the right direction entails working to transcend the sorts of internal politics and game playing that dominates traditional organizations. In other words it means fostering openness. (Senge 1990; Smith, 2001) This implies that control and decision-making is most effective at a local level in the hands of those that can best create optimal solutions to the issues at hand. Team Learning Senge (1990) acknowledges that teams, not individuals, are the fundamental learning unit in modern organizations. (p. 10) Heathfield (2006) believes that the dialogue among the members of the team results in stretching the ability of the organization to grow and develop. When teams learn together, Peter Senge suggests, not only can there be good results for the organization, members will grow more rapidly than could have occurred otherwise. (Smith, 2001)

Zink, 30 Shared Vision Senges view of shared vision involves a collective buy-in from the entire organization. This buy-in is unconditional and offers the organizations members guidance and hope for the future. It is a vision of the utopian state in a sense. (Heathfield, 2006) Peter Senge (1990) starts from the position that if any one idea about leadership has inspired organizations for thousands of years, its the capacity to hold a shared picture of the future we seek to create (p. 9). Such a vision has the power to be uplifting and to encourage experimentation and innovation. (Smith, 2001) Systems Thinking A great virtue of Peter Senges work is the manner in which he puts systems theory to work. (Smith, 2001) The underlying structure and the interlinking components of each of our work systems, shape a great deal of the behavior of the individuals who work inside of the work system. (Heathfield, 2006) Senges ability to direct focus holistically on organizational systems is a key component of his theoretical approach. Smith (2001) provides further context into systems thinking, Peter Senge argues that one of the key problems with much that is written about, and done in the name of management, is that rather simplistic frameworks are applied to what are complex systems. We tend to focus on the parts rather than seeing the whole, and to fail to see organization as a dynamic process. Thus, the argument runs, a better appreciation of systems will lead to more appropriate action. ( 19) The concept of systemic thinking is one of Senges key contributions to this area of study. John Van Maurik (2001) suggested that Peter Senge has been ahead of his time and that his arguments are insightful and revolutionary. (p. 201) He goes on to say that it is a matter of regret that more organizations have not taken his advice and have remained geared to the quick fix. OLM builds on his groundbreaking theory by taking the next step through extending the model to apply to organizational strategy and structure, while offering real world application tactics. Furthermore, Smith (2001) offers a view of the benefits that Senge has brought to the table. We can make some judgments about the possibilities of his theories and proposed practices. We could say that while there are some issues and problems with his conceptualization, at least it does carry within it some questions around what might make for human flourishing. The emphasis on building a shared vision, team working, personal mastery and the development of more sophisticated mental models and the way he runs the notion of dialogue through these does have the potential of allowing workplaces to be more convivial and creative. ( 55) Capitalizing on this potential is truly in the hands of organizational strategists and they are accountable for nothing short of excellence in driving stakeholder value. OLM enhances the capability of organizational effectiveness in this regard as leaders attempt to leverage this opportunity.