Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Election Law

Uploaded by

Kelsey Olivar MendozaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Election Law

Uploaded by

Kelsey Olivar MendozaCopyright:

Available Formats

[G.R. No. 122013. March 26, 1997] JOSE C. RAMIREZ, petitioner, vs.

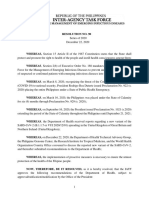

COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, MUNICIPAL BOARD OF CANVASSERS OF GIPORLOS, EASTERN SAMAR and ALFREDO I. GO, respondents. DECISION MENDOZA, J.: Petitioner Jose C. Ramirez and private respondent Alfredo I. Go were candidates for vice mayor of Giporlos, Eastern Samar in the election of May 8, 1995. Petitioner was proclaimed winner by the Municipal Board of Canvassers (MBC) on the basis of results showing that he obtained 1,367 votes against private respondents 1,235 votes.[1] On May 16, 1995, private respondent filed in the COMELEC a petition for the correction of what he claimed was manifest error in the Statement of Votes (SPC No. 95-198). He alleged that, based on the entries in the Statement of Votes, he obtained 1,515 votes as against petitioners 1,367 votes but that because of error in addition, he was credited with 1,235 votes as shown in the following recomputation:[2] Precinct No. 8-A 9 8 2-A 12 12-A 7-A 20 3 1-A 13-A 18 14 4 5-A 13 23 23 37 31 50 65 36 7 88 54 43 39 19 27 43 37 Go, Alfredo I. Ramirez, Jose C. 43 10 49 48 42 29 73 19 56 67 47 12 65 37 67 42

2 15 11 11-A 6 1 17 7 10 5 19 21 16 Total 29 Precincts

73 49 58 66 115 130 54 86 60 50 41 59 52 1,235

79 49 18 32 98 52 15 67 13 55 61 46 76 1,367 (Should be 1,515)

In his Answer with Counter-Protest,[3] petitioner Jose C. Ramirez disputed private respondents claim. He said that instead of the total of the votes for private respondent Alfredo Go, it was actually the entries relating to the number of votes credited to him in Precinct Nos. 11, 11-A, 6, 1, 17, 7, and 10 which were erroneously reflected in the Statement of Votes. According to petitioner, the entries in the Statement of Votes actually referred to the number of votes obtained by Rodito Fabillar, a mayoralty candidate, and not to the votes obtained by private respondent. Petitioner alleged that, as shown in the Certificate of Votes prepared by the Board of Election Inspectors, the votes cast for Go in the precincts in question were as follows: Precinct Nos. Per Statement of Votes 11 11-A 6 58 66 115 Per Certificate of Votes 32 18 65

1 17 7 10

130 54 86 60

61 48 37 28

Votes, like SPC No. 95-198 is a pre-proclamation controversy in none of the cases[8] cited to support this proposition was the issue the correction of a manifest error in the Statement of Votes under 231 of the Omnibus Election Code (B.P. Blg. 881) or 15 of R.A. No. 7166. On the other hand, Rule 27, 5 of the 1993 Rules of the COMELEC expressly provides that preproclamation controversies involving, inter alia, manifest errors in the tabulation or tallying of the results may be filed directly with the COMELEC en banc, thus 5. Pre-proclamation Controversies Which May Be Filed Directly With the Commission. (a) The following pre-proclamation controversies may be filed directly with the Commission: .... 2) When the issue involves the correction of manifest errors in the tabulation or tallying of the results during the canvassing as where (1) a copy of the election returns or certificate of canvass was tabulated more than once, (2) two or more copies of the election returns of one precinct, or two or more copies of certificate of canvass were tabulated separately, (3) there had been a mistake in the copying of the figures into the statement of votes or into the certificate of canvass, or (4) so-called returns from non-existent precincts were included in the canvass, and such errors could not have been discovered during the canvassing despite the exercise of due diligence and proclamation of the winning candidates had already been made. .... (e) The petition shall be heard and decided by the Commission en banc. .... Accordingly in Castromayor v. Commission on Elections,[9] and Mentang v. Commission on Elections,[10] this Court approved the assumption of jurisdiction by the COMELEC en banc over petitions for correction of manifest error directly filed with it. Our decision today in Torres v.COMELEC[11] again gives imprimatur to the exercise by the COMELEC en banc of the power to decide petition for correction of manifest error. In any event, petitioner is estopped from raising the issue of jurisdiction of the COMELEC en banc. Not only did he participate in the proceedings below but he also sought affirmative relief from the COMELEC en banc by filing a Counter-Protest in which he asked that entr[ies] in the statement of votes for Precinct Nos. 11, 11-A, 6, 1, 17, 7 and 10, be properly corrected for the petitioner, to reflect the correct mandate of the electorate of Giporlos, Eastern Samar. [12] It is certainly not right for a party taking part in proceedings and submitting his case for decision to attack the decision later for lack of jurisdiction of the tribunal because the decision turns out to be adverse to him.[13] Petitioner next contends that motu proprio the MBC already made a correction of the errors in the Statement of Votes in its certification dated May 22, 1995, which reads:[14] CERTIFICATION To whom It May Concern: This is to certify that the hereunder candidates for Municipal Vice Mayor of Giporlos, Eastern Samar during the May 8, 1995 National and Local Elections got the number of Votes on the precincts listed hereunder in tabulation form based in our Canvassing of Votes per Precincts.

The addition of the number of votes (reflected in the Certificate of Votes) to the number of votes from other precincts confirms the MBCs certificate that the total number of votes cast was actually 1,367 for petitioner and 1,235 for private respondent. On August 1, 1995, the COMELEC en banc issued its first questioned resolution, directing the MBC to reconvene and recompute the votes in the Statement of Votes and proclaim the winning candidate for vice mayor of Giporlos, Eastern Samar accordingly. [4] Petitioner Jose C. Ramirez and public respondent Municipal Board of Canvassers filed separate motions for clarification. On September 26, 1995, the COMELEC en banc issued its second questioned resolution, reiterating its earlier ruling. It rejected the MBCs recommendation to resort to election returns:[5] The Municipal Board of Canvassers is reminded that pursuant to Section 231 of the Omnibus Election Code, it is the Statement of Votes, duly prepared, accomplished during the canvass proceedings, and certified true and correct by said Board which supports and form (sic) the basis of the Certificate of Canvass and Proclamation of winning candidates. In fact and in deed, the Municipal Board of Canvassers/Movant had submitted to the Commission, attached to and forming part of the Certificate of Canvass and Proclamation a Statement of Votes without any notice of any discrepancy or infirmity therein. To claim now that the proclamation was not based on said Statement of Votes but on the Certificate of Votes because the entries in the Statement of Votes are erroneous is too late a move, considering that by the Boards act of submitting said Statement of Votes as attachment to the Certificate of Proclamation and Canvass, it had rendered regularity and authenticity thereto. Hence this petition for certiorari and mandamus seeking the annulment of the two resolutions, dated August 1, 1995 and September 26, 1995, of the Commission on Elections, and the reinstatement instead of the May 10, 1995 proclamation of petitioner Jose C. Ramirez as the duly elected vice mayor of Giporlos, Eastern Samar. Petitioner contends that (1) the COMELEC acted without jurisdiction over SPC No. 95-198 because the case was resolved by it without having been first acted upon by any of its divisions, and (2) the MBC had already made motu proprioa correction of manifest errors in the Statement of Votes in its certification dated May 22, 1995, showing the actual number of votes garnered by the candidates and it was a grave abuse of its discretion for the COMELEC to order a recomputation of votes based on the allegedly uncorrected Statement of Votes. With respect to the first ground of the petition, Art. IX, 3 of the Constitution provides: 3. The Commission on Elections may sit en banc or in two divisions, and shall promulgate its rules of procedure in order to expedite disposition of election cases, including pre-proclamation controversies. All such election cases shall be heard and decided in division, provided that motions for reconsideration of decisions shall be decided by the Comelec en banc. (Emphasis added) Although in Ong, Jr. v. COMELEC it was said that By now it is settled that election cases which include pre-proclamation controversies must first be heard and decided by a division of the Commission[7] and a petition for correction of manifest error in the Statement of

[6]

Name of candidate A : 6 : GO, I. RAMIREZ, C. : 1 : : 17 32 : : 7 18 : 11 : 10 : 11-

PRECINCT NUMBERS

65 : 61 :

48

: 37

Alfredo 28 Jose

returns,[16] there is no reason for their use in this case since the integrity of the election returns is not in question. On the other hand, in the canvass of votes, the MBC is directed to use the election returns.[17] Accordingly, in revising the Statement of Votes supporting the Certificate of Canvass, the MBC should have used the election returns from the precincts in question although in fairness to MBC, it proposed the use of election returns but the COMELEC en banc rejected the proposal. The Statement of Votes is a tabulation per precinct of votes garnered by the candidates as reflected in the election returns. The Statement of Votes is a vital component of the electoral process. It supports the Certificate of Canvass and is the basis for proclamation. [18] But in this case the Statement of Votes was not even prepared until after the proclamation of the winning candidate. This is contrary to the Omnibus Election Code, 231 of which provides in part: . . . . The respective board of canvassers shall prepare a certificate of canvass duly signed and affixed with the imprint of the thumb of the right hand of each member, supported by a statement of votes received by each candidate in each polling place and, on the basis thereof, shall proclaim as elected the candidates who obtained the highest number of votes cast in the province, city, municipality or barangay. Indeed, it appears from the Comment of the MBC that the MBC prepared its Certificate of Canvass simply on the basis of improvised tally sheets and that it was only after the termination of the canvass, the proclamation of petitioner Jose C. Ramirez, and the accomplishment of the Certificate of Canvass of Votes and Proclamation, that its clerk, Rosalia Abenojar, prepared the Statement of Votes (C.E. Form No. 20-A). In a sworn report, Ms. Abenojar herself stated that she was tired and drowsy at the time she prepared the Statement of Votes for the mayoralty and vice mayoralty positions. Although this circumstance may support petitioners claim that the number of votes credited to private respondent Alfredo I. Go are actually those cast in Precinct Nos. 11, 11-A, 6, 1, 17, 7, and 10 for mayoralty candidate Rodito Fabillar, it is equally possible that Go and Fabillar obtained the same number of votes in those precincts. That the clerk who prepared the Statement of Votes was tired and drowsy does not necessarily mean the entries she made were erroneous. But what is clear is that the Statement of Votes was not prepared with the care required by its importance. Accordingly, as the Solicitor General states, what the COMELEC should have ordered the MBC to do was not merely to recompute the number of votes for the parties, but to revise the Statement of Votes, using the election returns for this purpose.[19] As this Court ruled in Villaroya v. Commission on Elections:[20] [T]he COMELEC has ample power to see to it that the elections are held in clean and orderly manner and it may decide all questions affecting the elections and has original jurisdiction on all matters relating to election returns, including the verification of the number of votes received by opposing candidates in the election returns as compared to the statement of votes in order to insure that the true will of the people is known. Such a clerical error in the statement of votes can be ordered corrected by the COMELEC. (Emphasis added) Petitioners final contention that in any event SPC No. 95-198 must be considered rendered moot and academic by reason of his proclamation and assumption of office is untenable. The short answer to this is that petitioners proclamation was null and void and therefore the COMELEC was not barred from inquiring into its nullity.[21] WHEREFORE, the petition is partially GRANTED by annulling the resolutions dated August 1, 1995 and September 26, 1995 of the Commission on Elections. The COMELEC is instead DIRECTED to reconvene the Municipal Board of Canvassers or, if this is not feasible, to constitute a new Municipal Board of Canvassers in Giporlos, Eastern Samar and to order it to revise with deliberate speed the Statement of Votes on the basis of the election returns from all precincts of the Municipality of Giporlos and thereafter proclaim the winning candidate on the basis thereof. SO ORDERED.

18

32

98 : 52 : 15

: 67

: 13

This certification is issued upon request of the interested party for whatever legal purpose this may serve him. Giporlos, Eastern Samar. May 22, 1995 To begin with, the corrections should be made either by inserting corrections in the Statement of Votes which was originally prepared and submitted by the MBC, or by preparing an entirely new Statement of Votes incorporating therein the corrections. [15] The certification issued by the MBC is thus not the proper way to correct manifest errors in the Statement of Votes. More importantly, the corrections should be based on the election returns but here the corrections appear to have been made by the MBC on the bases of the Certificates of Votes issued. Thus, in its motion for clarification, the MBC said: a. The proclamation of Jose C. Ramirez was based on the results of the certificate of canvass and tally of votes garnered by both petitioner and private respondent which showed Jose C. Ramirez garnering 1,367 as against 1,235 by Alfredo I. Go, or a winning margin of 132 in favor of Jose C. Ramirez; b. Based on the certificate of votes in Precinct Nos. 11, 11-A, 6, 1, 17, 7, and 10,, Alfredo I. Go garnered only 32,18, 65,61,48,37 and 28, respectively, and the votes ascribed to the latter shown in the statement of votes are clear typographical errors and were erroneously copied from the votes garnered by mayoral candidate Rodito P. Fabillar from the same seven (7) precincts in Giporlos; c. Because of typographical errors in the statement of votes, Alfredo I. Go balooned (sic) by 280 votes, such that instead of losing by 132 votes to Jose C. Ramirez, Alfredo I. Go acquired an unwarranted margin of 148 votes; d. The recomputation based on the statement of votes alone without including the correct votes on the Election Returns on the Seven (7) precincts aforesaid will frustrate the will of the people who unquestionably voted for Jose C. Ramirez by a clear majority of 132 votes; e. In the preparation of the certificate of canvass and proclamation, only the certificate of votes of each candidate were considered by reason of the fact it was prepared and signed only on May 11,1995 or one after (sic) the proclamation of the winning municipal candidates on May 10, 1995. Certificates of Votes are issued by Boards of Election Inspectors (BEI) to watchers, pursuant to 215 of the Omnibus Election Code (OEC). While such certificates are useful for showing tampering, alteration, falsification or any other irregularity in the preparation of election

[G.R. No. 125955. June 19, 1997] WILMER GREGO, petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and HUMBERTO BASCO, respondents. DECISION ROMERO, J.: The instant special civil action for certiorari and prohibition impugns the resolution of the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) en banc in SPA No. 95-212 dated July 31, 1996, dismissing petitioners motion for reconsideration of an earlier resolution rende red by the COMELECs First Division on October 6, 1995, which also dismissed the petition for disqualification[1] filed by petitioner Wilmer Grego against private respondent Humberto Basco. The essential and undisputed factual antecedents of the case are as follows: On October 31, 1981, Basco was removed from his position as Deputy Sheriff by no less than this Court upon a finding of serious misconduct in an administrative complaint lodged by a certain Nena Tordesillas. The Court held: WHEREFORE, FINDING THE RESPONDENT DEPUTY SHERIFF HUMBERTO BASCO OF THE CITY COURT OF MANILA GUILTY OF SERIOUS MISCONDUCT IN OFFICE FOR THE SECOND TIME, HE IS HEREBY DISMISSED FROM THE SERVICE WITH FORFEITURE OF ALL RETIREMENT BENEFITS AND WITH PREJUDICE TO REINSTATEMENT TO ANY POSITION IN THE NATIONAL OR LOCAL GOVERNMENT, INCLUDING ITS AGENCIES AND INSTRUMENTALITIES, OR GOVERNMENT-OWNED OR CONTROLLED CORPORATIONS. x x x x x x[2] x x x

The COMELEC conducted a hearing of the case on May 14, 1995, where it ordered the parties to submit simultaneously their respective memoranda. Before the parties could comply with this directive, however, the Manila City BOC proclaimed Basco on May 17, 1995, as a duly elected councilor for the Second District of Manila, placing sixth among several candidates who vied for the seats.[5] Basco immediately took his oath of office before the Honorable Ma. Ruby Bithao-Camarista, Presiding Judge, Metropolitan Trial Court, Branch I, Manila. In view of such proclamation, petitioner lost no time in filing an Urgent Motion seeking to annul what he considered to be an illegal and hasty proclamation made on May 17, 1995, by the Manila City BOC. He reiterated Bascos disqualification and prayed anew that candidate Romualdo S. Maranan be declared the winner. As expected, Basco countered said motion by filing his Urgent Opposition to: Urgent Motion (with Reservation to Submit Answer and/or Motion to Dismiss Against Instant Petition for Disqualification with Temporary Restraining Order). On June 5, 1995, Basco filed his Motion to Dismiss Serving As Answer pursuant to the reservation he made earlier, summarizing his contentions and praying as follows: Respondent thus now submits that the petitioner is not entitled to relief for the following reasons: 1. The respondent cannot be disqualified on the ground of Section 40 paragraph b of the Local Government Code because the Tordesillas decision is barred by laches, prescription, res judicata, lis pendens, bar by prior judgment, law of the case and stare decisis; 2. Section 4[0] par. B of the Local Government Code may not be validly applied to persons who were dismissed prior to its effectivity. To do so would make it ex post facto, bill of attainder, and retroactive legislation which impairs vested rights. It is also a class legislation and unconstitutional on the account. 3. Respondent had already been proclaimed. And the petition being a preproclamation contest under the Marquez v. Comelec Ruling, supra, it should be dismissed by virtue of said pronouncement. 4. Respondents three-time election as candidate for councilor constitutes implied pardon by the people of previous misconduct (Aguinaldo v. Comelec G.R. 105128; Rice v. State 161 SCRA 401; Montgomery v. Newell 40 SW 2d 4181; People v. Bashaw 130 P. 2nd 237, etc.). 5. As petition to nullify certificate of candidacy, the instant case has prescribed; it was premature as an election protest and it was not brought by a proper party in interest as such protest.: PRAYER WHEREFORE it is respectfully prayed that the instant case be dismissed on instant motion to dismiss the prayer for restraining order denied (sic). If this Honorable Office is not minded to dismiss, it is respectfully prayed that instant motion be considered as respondents answer. All other reliefs and remedies just and proper in the premises are likewise hereby prayed for. After the parties respective memoranda had been filed, the COMELECs First Division resolved to dismiss the petition for disqualification on October 6, 1995, ruling that the administrative penalty imposed by the Supreme Court on respondent Basco on October 31, 1981 was wiped away and condoned by the electorate which elected him and that on account of Bascos proclamation on May 17, 1965, as the sixth duly elected councilor of the Second District of Manila, the petition would no longer be viable.[6]

Subsequently, Basco ran as a candidate for Councilor in the Second District of the City of Manila during the January 18, 1988, local elections. He won and, accordingly, assumed office. After his term, Basco sought re-election in the May 11, 1992 synchronized national elections. Again, he succeeded in his bid and he was elected as one of the six (6) City Councilors. However, his victory this time did not remain unchallenged. In the midst of his successful re-election, he found himself besieged by lawsuits of his opponents in the polls who wanted to dislodge him from his position. One such case was a petition for quo warranto[3] filed before the COMELEC by Cenon Ronquillo, another candidate for councilor in the same district, who alleged Bascos ineligibility to be elected councilor on the basis of the Tordesillas ruling. At about the same time, two more cases were also commenced by Honorio Lopez II in the Office of the Ombudsman and in the Department of Interior and Local Government.[4] All these challenges were, however, dismissed, thus, paving the way for Bascos continued stay in office. Despite the odds previously encountered, Basco remained undaunted and ran again for councilor in the May 8, 1995, local elections seeking a third and final term. Once again, he beat the odds by emerging sixth in a battle for six councilor seats. As in the past, however, his right to office was again contested. On May 13, 1995, petitioner Grego, claiming to be a registered voter of Precinct No. 966, District II, City of Manila, filed with the COMELEC a petition for disqualification, praying for Bascos disqualification, for the suspension of his proclamation, and for the declaration of Romualdo S. Maranan as the sixth duly elected Councilor of Manilas Second District. On the same day, the Chairman of the Manila City Board of Canvassers (BOC) was duly furnished with a copy of the petition. The other members of the BOC learned about this petition only two days later.

Petitioners motion for reconsideration of said resolution was later denied by the COMELEC en banc in its assailed resolution promulgated on July 31, 1996.[7] Hence, this petition. Petitioner argues that Basco should be disqualified from running for any elective position since he had been removed from office as a result of an administrative case pursuant to Section 40 (b) of Republic Act No. 7160, otherwise known as the Local Government Code (the Code), which took effect on January 1, 1992.[8] Petitioner wants the Court to likewise resolve the following issues, namely:

compelling reasons for us to depart therefrom. Thus, in Aguinaldo vs. COMELEC,[11] reiterated in the more recent cases of Reyes vs. COMELEC[12] and Salalima vs. Guingona, Jr.,[13] we ruled, thus: The COMELEC applied Section 40 (b) of the Local Government Code (Republic Act 7160) which provides: Sec. 40. positions: (b) The following persons are disqualified from running for any elective local

Those removed from office as a result of an administrative case.

1. Whether or not Section 40 (b) of Republic Act No. 7160 applies retroactively to those removed from office before it took effect on January 1, 1992; 2. Whether or not private respondents election in 1988, 1992 and in 1995 as City Councilor of Manila wiped away and condoned the administrative penalty against him; 3. Whether or not private respondents proclamation as sixth winning candidate on May 17, 1995, while the disqualification case was still pending consideration by COMELEC, is void ab initio; and 4. Whether or not Romualdo S. Maranan, who placed seventh among the candidates for City Councilor of Manila, may be declared a winner pursuant to Section 6 of Republic Act No. 6646. While we do not necessarily agree with the conclusions and reasons of the COMELEC in the assailed resolution, nonetheless, we find no grave abuse of discretion on its part in dismissing the petition for disqualification. The instant petition must, therefore, fail. We shall discuss the issues raised by petitioner in seriatim. I. Does Section 40 (b) of Republic Act No. 7160 apply retroactively to those removed from office before it took effect on January 1, 1992? Section 40 (b) of the Local Government Code under which pet itioner anchors Bascos alleged disqualification to run as City Councilor states: SEC. 40. Disqualifications. - The following persons are disqualified from running for any elective local position:

Republic Act 7160 took effect only on January 1, 1992. The rule is: x x x Well-settled is the principle that while the Legislature has the power to pass retroactive laws which do not impair the obligation of contracts, or affect injuriously vested rights, it is equally true that statutes are not to be construed as intended to have a retroactive effect so as to affect pending proceedings, unless such intent is expressly declared or clearly and necessarily implied from the language of the enactment. x x x (Jones vs. Summers, 105 Cal. App. 51, 286 Pac. 1093; U.S. vs. Whyel 28 (2d) 30; Espiritu v. Cipriano, 55 SCRA 533 [1974], cited in Nilo vs. Court of Appeals, 128 SCRA 519 [1974]. See also Puzon v. Abellera, 169 SCRA 789 [1989]; Al-Amanah Islamic Investment Bank of the Philippines v. Civil Service Commission, et al., G.R. No. 100599, April 8, 1992). There is no provision in the statute which would clearly indicate that the same operates retroactively. It, therefore, follows that [Section] 40 (b) of the Local Government Code is not applicable to the present case. (Underscoring supplied). That the provision of the Code in question does not qualify the date of a candidates removal from office and that it is couched in the past tense should not deter us from the applying the law prospectively. The basic tenet in legal hermeneutics that laws operate only prospectively and not retroactively provides the qualification sought by petitioner. A statute, despite the generality in its language, must not be so construed as to overreach acts, events or matters which transpired before its passage. Lex prospicit, non respicit. The law looks forward, not backward.[14] II. Did private respondents election to office as City Councilor of Manila in the 1988, 1992 and 1995 elections wipe away and condone the administrative penalty against him, thus restoring his eligibility for public office? Petitioner maintains the negative. He quotes the earlier ruling of the Court in Frivaldo v. COMELEC[15] to the effect that a candidates disqualification cannot be erased by the electorate alone through the instrumentality of the ballot. Thus: x x x (T)he qualifications prescribed for elective office cannot be erased by the electorate alone. The will of the people as expressed through the ballot cannot cure the vice of ineligibility, especially if they mistakenly believed, as in this case, that the candidate was qualified. x x x At first glance, there seems to be a prima facie semblance of merit to petitioners argument. However, the issue of whether or not Bascos triple election to office cure d his alleged ineligibility is actually beside the point because the argument proceeds on the assumption that he was in the first place disqualified when he ran in the three previous elections. This assumption, of course, is untenable considering that Basco was NOT subject to any

(b)

Those removed from office as a result of an administrative case;

In this regard, petitioner submits that although the Code took effect only on January 1, 1992, Section 40 (b) must nonetheless be given retroactive effect and applied to Bascos dismissal from office which took place in 1981. It is stressed that the provision of the law as worded does not mention or even qualify the date of removal from office of the candidate in order for disqualification thereunder to attach. Hence, petitioner impresses upon the Court that as long as a candidate was once removed from office due to an administrative case, regardless of whether it took place during or prior to the effectivity of the Code, the disqualification applies.[9] To him, this interpretation is made more evident by the manner in which the provisions of Section 40 are couched. Since the past tense is used in enumerating the grounds for disqualification, petitioner strongly contends that the provision must have also referred to removal from office occurring prior to the effectivity of the Code.[10] We do not, however, subscribe to petitioners view. Our refusal to give retroactive application to the provision of Section 40 (b) is already a settled issue and there exist no

disqualification at all under Section 40 (b) of the Local Government Code which, as we said earlier, applies only to those removed from office on or after January 1, 1992. In view of the irrelevance of the issue posed by petitioner, there is no more reason for the Court to still dwell on the matter at length. Anent Bascos alleged circumvention of the prohibition in Tordesillas against reinstatement to any position in the national or local government, including its agencies and instrumentalities, as well as government-owned or controlled corporations, we are of the view that petitioners contention is baseless. Neither does petitioners argument that the term any position is broad enough to cover without distinction both appointive and local positions merit any consideration. Contrary to petitioners assertion, the Tordesillas decision did not bar Basco from running for any elective position. As can be gleaned from the decretal portion of the said decision, the Court couched the prohibition in this wise: x x x AND WITH PREJUDICE TO REINSTATEMENT TO ANY POSITION IN THE NATIONAL OR LOCAL GOVERNMENT, INCLUDING ITS AGENCIES AND INSTRUMENTALITIES, OR GOVERNMENT-OWNED OR CONTROLLED CORPORATIONS. In this regard, particular attention is directed to the use of the term reinstatement. Under the former Civil Service Decree,[16] the law applicable at the time Basco, a public officer, was administratively dismissed from office, the term reinstatement had a technical meaning, referring only to an appointive position. Thus: ARTICLE VIII. PERSONNEL POLICIES AND STANDARDS. SEC. 24. Personnel Actions. -

We are not convinced. The provisions and cases cited are all misplaced and quoted out of context. For the sake of clarity, let us tackle each one by one. Section 20, paragraph (i) of Rep. Act 7166 reads: SEC. 20. Procedure in Disposition of Contested Election Returns. -

(i) The board of canvassers shall not proclaim any candidate as winner unless authorized by the Commission after the latter has ruled on the objections brought to it on appeal by the losing party. Any proclamation made in violation hereof shall be void ab initio, unless the contested returns will not adversely affect the results of the election.

The inapplicability of the abovementioned provision to the present case is very much patent on its face considering that the same refers only to a void proclamation in relation to contested returns and NOT to contested qualifications of a candidate. Next, petitioner cites Section 6 of Rep. Act 6646 which states: SEC. 6. Effect of Disqualification Case. - Any candidate who has been declared by final judgment to be disqualified shall not be voted for, and the votes cast for him shall not be counted. If for any reason, a candidate is not declared by final judgment before an election to be disqualified and he is voted for and receives the winning number of votes in such election, the Court or Commission shall continue with the trial and hearing of the action, inquiry or protest and, upon motion of the complainant or any intervenor, may during the pendency thereof order the suspension of the proclamation of such candidate whenever the evidence of his guilt is strong. (Underscoring supplied). This provision, however, does not support petitioners contention that the COMELEC, or more properly speaking, the Manila City BOC, should have suspended the proclamation. The use of the word may indicates that the suspension of a proclamation is merely directory and permissive in nature and operates to confer discretion.[21] What is merely made mandatory, according to the provision itself, is the continuation of the trial and hearing of the action, inquiry or protest. Thus, in view of this discretion granted to the COMELEC, the question of whether or not evidence of guilt is so strong as to warrant suspension of proclamation must be left for its own determination and the Court cannot interfere therewith and substitute its own judgment unless such discretion has been exercised whimsically and capriciously.[22] The COMELEC, as an administrative agency and a specialized constitutional body charged with the enforcement and administration of all laws and regulations relative to the conduct of an election, plebiscite, initiative, referendum, and recall,[23] has more than enough expertise in its field that its findings or conclusions are generally respected and even given finality.[24] The COMELEC has not found any ground to suspend the proclamation and the records likewise fail to show any so as to warrant a different conclusion from this Court. Hence, there is no ample justification to hold that the COMELEC gravely abused its discretion. It is to be noted that Section 5, Rule 25 of the COMELEC Rules of Procedure[25] states that: SEC. 5. Effect of petition if unresolved before completion of canvass. - x x x (H)is proclamation shall be suspended notwithstanding the fact that he received the winning number of votes in such election. However, being merely an implementing rule, the same must not override, but instead remain consistent with and in harmony with the law it seeks to apply and implement. Administrative rules and regulations are intended to carry out, neither to supplant nor to modify, the law.[26] Thus, in Miners Association of the Philippines, Inc. v. Factoran, Jr.,[27] the Court ruled that:

(d) Reinstatement. - Any person who has been permanently APPOINTED to a position in the career service and who has, through no delinquency or misconduct, been separated therefrom, may be reinstated to a position in the same level for which he is qualified.

(Emphasis and underscoring supplied). The Rules on Personnel Actions and Policies issued by the Civil Service Commission on November 10, 1975,[17] provides a clearer definition. It reads: RULE VI. OTHER PERSONNEL ACTIONS. SEC. 7. Reinstatement is the REAPPOINMENT of a person who was previously separated from the service through no delinquency or misconduct on his part from a position in the career service to which he was permanently appointed, to a position for which he is qualified. (Emphasis and underscoring supplied). In light of these definitions, there is, therefore, no basis for holding that Basco is likewise barred from running for an elective position inasmuch as what is contemplated by the prohibition in Tordesillas is reinstatement to an appointive position. III. Is private respondents proclamation as sixth winning candidate on May 17, 1995, while the disqualification case was still pending consideration by COMELEC, void ab initio? To support its position, petitioner argues that Basco violated the provisions of Section 20, paragraph (i) of Republic Act No. 7166, Section 6 of Republic Act No. 6646, as well as our ruling in the cases of Duremdes v. COMELEC,[18] Benito v. COMELEC[19] and Aguam v. COMELEC.[20]

We reiterate the principle that the power of administrative officials to promulgate rules and regulations in the implementation of a statute is necessarily limited only to carrying into effect what is provided in the legislative enactment. The principle was enunciated as early as 1908 in the case of United States v. Barrias. The scope of the exercise of such rule-making power was clearly expressed in the case of United States v. Tupasi Molina, decided in 1914, thus: Of course, the regulations adopted under legislative authority by a particular department must be in harmony with the provisions of the law, and for the sole purpose of carrying into effect its general provisions. By such regulations, of course, the law itself can not be extended. So long, however, as the regulations relate solely to carrying into effect the provision of the law, they are valid. Recently, the case of People v. Maceren gave a brief delineation of the scope of said power of administrative officials: Administrative regulations adopted under legislative authority by a particular department must be in harmony with the provisions of the law, and should be for the sole purpose of carrying into effect its general provisions. By such regulations, of course, the law itself cannot be extended (U.S. v. Tupasi Molina, supra). An administrative agency cannot amend an act of Congress (Santos v. Estenzo, 109 Phil. 419, 422; Teoxon vs. Members of the Board of Administrators, L-25619, June 30, 1970, 33 SCRA 585; Manuel vs. General Auditing Office, L28952, December 29, 1971, 42 SCRA 660; Deluao vs. Casteel, L-21906, August 29, 1969, 29 SCRA 350). The rule-making power must be confined to details for regulating the mode or proceeding to carry into effect the law as it has been enacted. The power cannot be extended to amending or expanding the statutory requirements or to embrace matters not covered by the statute. Rules that subvert the statute cannot be sanctioned (University of Santo Tomas v. Board of Tax Appeals, 93 Phil. 376, 382, citing 12 C.J. 845-46. As to invalid regulations, see Collector of Internal Revenue v. Villaflor, 69 Phil. 319; Wise & Co. v. Meer, 78 Phil. 655, 676; Del Mar v. Phil. Veterans Administration, L-27299, June 27, 1973, 51 SCRA 340, 349). x x x xxx x x x The rule or regulations should be within the scope of the statutory authority granted by the legislature to the administrative agency (Davis, Administrative Law, p. 194, 197, cited in Victorias Milling Co., Inc. v. Social Security Commission, 114 Phil. 555, 558). In case of discrepancy between the basic law and a rule or regulation issued to implement said law, the basic law prevails because said rule or regulations cannot go beyond the terms and provisions of the basic law (People v. Lim, 108 Phil. 1091). Since Section 6 of Rep. Act 6646, the law which Section 5 of Rule 25 of the COMELEC Rules of Procedure seeks to implement, employed the word may, it is, therefore, improper and highly irregular for the COMELEC to have used instead the word shall in its rules. Moreover, there is no reason why the Manila City BOC should not have proclaimed Basco as the sixth winning City Councilor. Absent any determination of irregularity in the election returns, as well as an order enjoining the canvassing and proclamation of the winner, it is a mandatory and ministerial duty of the Board of Canvassers concerned to count the votes based on such returns and declare the result. This has been the rule as early as in the case of Dizon v. Provincial Board of Canvassers of Laguna[28] where we clarified the nature of the functions of the Board of Canvassers, viz.: The simple purpose and duty of the canvassing board is to ascertain and declare the apparent result of the voting. All other questions are to be tried before the court or other tribunal for contesting elections or in quo warranto proceedings. (9 R.C.L., p. 1110) x x x

To the same effect is the following quotation: x x x Where there is no question as to the genuineness of the returns or that all the returns are before them, the powers and duties of canvassers are limited to the mechanical or mathematical function of ascertaining and declaring the apparent result of the election by adding or compiling the votes cast for each candidate as shown on the face of the returns before them, and then declaring or certifying the result so ascertained. (20 C.J., 200-201) [Underscoring supplied] Finally, the cases of Duremdes, Benito and Aguam, supra, cited by petitioner are all irrelevant and inapplicable to the factual circumstances at bar and serve no other purpose than to muddle the real issue. These three cases do not in any manner refer to void proclamations resulting from the mere pendency of a disqualification case. In Duremdes, the proclamation was deemed void ab initio because the same was made contrary to the provisions of the Omnibus Election Code regarding the suspension of proclamation in cases of contested election returns. In Benito, the proclamation of petitioner Benito was rendered ineffective due to the Board of Canvassers violation of its ministerial duty to proclaim the candidate receiving the highest number of votes and pave the way to succession in office. In said case, the candidate receiving the highest number of votes for the mayoralty position died but the Board of Canvassers, instead of proclaiming the deceased candidate winner, declared Benito, a mere second-placer, the mayor. Lastly, in Aguam, the nullification of the proclamation proceeded from the fact that it was based only on advanced copies of election returns which, under the law then prevailing, could not have been a proper and legal basis for proclamation. With no precedent clearly in point, petitioners arguments must, therefore, be rejected. IV. candidate? May Romualdo S. Maranan, a seventh placer, be legally declared a winning

Obviously, he may not be declared a winner. In the first place, Basco was a duly qualified candidate pursuant to our disquisition above. Furthermore, he clearly received the winning number of votes which put him in sixth place. Thus, petitioners emphatic reference to Labo v. COMELEC,[29] where we laid down a possible exception to the rule that a second placer may be declared the winning candidate, finds no application in this case. The exception is predicated on the concurrence of two assumptions, namely: (1) the one who obtained the highest number of votes is disqualified; and (2) the electorate is fully aware in fact and in law of a candidates disqualification so as to bring such awareness within the realm of notoriety but would nonetheless cast their votes in favor of the ineligible candidate. Both assumptions, however, are absent in this case. Petitioners allegation that Basco was well -known to have been disqualified in the small community where he ran as a candidate is purely speculative and conjectural, unsupported as it is by any convincing facts of record to show notoriety of his alleged disqualification.[30] In sum, we see the dismissal of the petition for disqualification as not having been attended by grave abuse of discretion. There is then no more legal impediment for private respondents continuance in office as City Councilor for the Second District of Manila. WHEREFORE, the instant petition for certiorari and prohibition is hereby DISMISSED for lack of merit. The assailed resolution of respondent Commission on Elections (COMELEC) is SPA 95-212 dated July 31, 1996 is hereby AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner. SO ORDERED.

[G.R. No. 125249. February 7, 1997] JIMMY S. DE CASTRO, petitioner, vs. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and AMANDO A. MEDRANO, respondents. DECISION HERMOSISIMA, JR., J.: Before us is a petition for certiorari raising twin issues as regards the effect of the contestants death in an election protest: Is said contest a personal action extinguished upon the death of the real party in interest? If not, what is the mandatory period within which to effectuate the substitution of parties? The following antecedent facts have been culled from the pleadings and are not in dispute: Petitioner was proclaimed Mayor of Gloria, Oriental Mindoro during the May 8, 1995 elections. In the same elections, private respondent was proclaimed Vice-Mayor of the same municipality. On May 19, 1995, petitioners rival candidate, the late Nicolas M. Jamilla, filed an election protest[1] before the Regional Trial Court of Pinamalayan, Oriental Mindoro.[2] During the pendency of said contest, Jamilla died.[3] Four days after such death or on December 19, 1995, the trial court dismissed the election protest ruling as it did that [a]s th is case is personal, the death of the protestant extinguishes the case itself. The issue or issues brought out in this protest have become moot and academic.[4] On January 9, 1995, private respondent learned about the dismissal of the protest from one Atty. Gaudencio S. Sadicon, who, as the late Jamillas counsel, was the one who informed the trial court of his clients demise. On January 15, 1996, private respondent filed his Omnibus Petition/Motion (For Intervention and/or Substitution with Motion for Reconsideration).[5] Opposition thereto was filed by petitioner on January 30, 1996.[6] In an Order dated February 14, 1996,[7] the trial court denied private respondents Omnibus Petition/Motion and stubbornly held that an election protest being personal to the protestant, is ipso facto terminated by the latters death. Unable to agree with the trial courts dismissal of the election protest, private respondent filed a petition for certiorari and mandamus before the Commission on Elections (COMELEC); private respondent mainly assailed the trial court orders as having been issued with grave abuse of discretion. COMELEC granted the petition for certiorari and mandamus.[8] It ruled that an election contest involves both the private interests of the rival candidates and the public interest in the final determination of the real choice of the electorate, and for this reason, an election contest necessarily survives the death of the protestant or the protestee. We agree. It is true that a public office is personal to the public officer and is not a property transmissible to his heirs upon death.[9] Thus, applying the doctrine of actio personalis moritur cum persona, upon the death of the incumbent, no heir of his may be allowed to continue holding his office in his place. But while the right to a public office is personal and exclusive to the public officer, an election protest is not purely personal and exclusive to the protestant or to the protestee such that the death of either would oust the court of all authority to continue the protest proceedings. To finally dispose of this case, we rule that the filing by private respondent of his Omnibus Petition/Motion on January 15, 1996, well within a period of thirty days from December 19, 1995 when Jamillas counsel informed the trial court of Jamillas death, was in compliance with Section 17, Rule 3 of the Revised Rules of Court. Since the Rules of Court, though not generally applicable to election cases, may however be applied by analogy or in a suppletory character,[15] private respondent was correct to rely thereon. The above jurisprudence is not ancient; in fact these legal moorings have been recently reiterated in the 1991 case of De la Victoria vs. COMELEC.[16] If only petitioners diligence in An election contest, after all, involves not merely conflicting private aspirations but is imbued with paramount public interests. As we have held in the case of Vda. de De Mesa v. Mencias:[10] x x x. It is axiomatic that an election contest, involving as it does not only the adjudication and settlement of the private interests of the rival candidates but also the paramount need of dispelling once and for all the uncertainty that beclouds the real choice of the electorate with respect to who shall discharge the prerogatives of the offices within their gift, is a proceeding imbued with public interest which raises it onto a plane over and above ordinary civil actions. For this reason, broad perspectives of public policy impose upon courts the imperative duty to ascertain by all means within their command who is the real candidate elected in as expeditious a manner as possible, without being fettered by technicalities and procedural barriers to the end that the will of the people may not be frustrated (Ibasco vs. Ilao, et al., G.R. L-17512, December 29, 1960; Reforma vs. De Luna, G.R. L-13242, July 31, 1958). So inextricably intertwined are the interests of the contestants and those of the public that there can be no gainsaying the logic of the proposition that even the voluntary cessation in office of the protestee not only does not ipso facto divest him of the character of an adversary in the contest inasmuch as he retains a party interest to keep his political opponent out of the office and maintain therein his successor, but also does not in any manner impair or detract from the jurisdiction of the court to pursue the proceeding to its final conclusion (De Los Angeles vs. Rodriguez, 46 Phil. 595, 597; Salcedo vs. Hernandez, 62 Phil. 584, 587; Galves vs. Maramba, G.R. L-13206). Upon the same principle, the death of the protestee De Mesa did not abate the proceedings in the election protest filed against him, and it may stated as a rule that an election contest survives and must be prosecuted to final judgment despite the death of the protestee.[11] The death of the protestant, as in this case, neither constitutes a ground for the dismissal of the contest nor ousts the trial court of its jurisdiction to decide the election contest. Apropos is the following pronouncement of this court in the case of Lomugdang v. Javier:[12] Determination of what candidate has been in fact elected is a matter clothed with public interest, wherefore, public policy demands that an election contest, duly commenced, be not abated by the death of the contestant. We have squarely so rule in Sibulo Vda. de Mesa vs. Judge Mencias, G.R. No. L-24583, October 29, 1966, in the same spirit that led this Court to hold that the ineligibility of the protestant is not a defense (Caesar vs. Garrido, 53 Phil. 57), and that the protestees cessation in office is not a ground for the dismissal of the contest nor detract the Courts jurisdiction to decide the case (Angeles vs. Rodriguez, 46 Phil. 595; Salcedo vs. Hernandez, 62 Phil. 584).[13] The asseveration of petitioner that private respondent is not a real party in interest entitled to be substituted in the election protest in place of the late Jamilla, is utterly without legal basis. Categorical was our ruling in Vda. de Mesa and Lomugdang that: x x x the Vice Mayor elect has the status of a real party in interest in the continuation of the proceedings and is entitled to intervene therein. For if the protest succeeds and the protestee is unseated, the Vice-Mayor succeeds to the office of Mayor that becomes vacant if the one duly elected can not assume the post.[14]

updating himself with case law is as spirited as his persistence in pursuing his legal asseverations up to the highest court of the land, no doubt further derailment of the election protest proceedings could have been avoided. WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant petition for certiorari is hereby DISMISSED. Costs against petitioner. SO ORDERED.

You might also like

- Heritage Conservation and Architectural EducationDocument13 pagesHeritage Conservation and Architectural EducationKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Culture Interior ArchitectureDocument12 pagesCulture Interior ArchitectureKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Perception and Behavior: January 1984Document27 pagesEnvironmental Perception and Behavior: January 1984Kelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Economies: A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (Smes)Document24 pagesEconomies: A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (Smes)Kelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Engin Aesth ErgonomicsDocument20 pagesEngin Aesth ErgonomicsKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 3 Bank of America, NT & SA v. C.ADocument2 pages3 Bank of America, NT & SA v. C.AKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- c1 PDFDocument16 pagesc1 PDFSunilNo ratings yet

- IATF Resolution No. 90Document3 pagesIATF Resolution No. 90Steph GNo ratings yet

- Joselito Musni Puno vs. Puno Enterprises, IncDocument1 pageJoselito Musni Puno vs. Puno Enterprises, IncKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- BSP and Chuchi Fonacier vs. Hon. Nina G. ValenzuelaDocument2 pagesBSP and Chuchi Fonacier vs. Hon. Nina G. ValenzuelaKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Saturnino vs. Phil American LifeDocument2 pagesSaturnino vs. Phil American LifeKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 03 PNB Vs SorianoDocument2 pages03 PNB Vs SorianoKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 4 Schmitz Transport vs. Transport Venture, IncDocument2 pages4 Schmitz Transport vs. Transport Venture, IncKelsey Olivar Mendoza100% (1)

- Malayan Insurance vs. Pap Co. LTDDocument2 pagesMalayan Insurance vs. Pap Co. LTDKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Full TextDocument8 pagesFull TextKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank Trust Company v. ASBDocument9 pagesMetropolitan Bank Trust Company v. ASBKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 01 Sps Violago Vs BA Finance & ViolagoDocument2 pages01 Sps Violago Vs BA Finance & ViolagoKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 07 Fredco Manufacturing vs. Harvard UniversityDocument2 pages07 Fredco Manufacturing vs. Harvard UniversityKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 06 Ching vs. CADocument2 pages06 Ching vs. CAKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- PROPERTY CasesDocument6 pagesPROPERTY CasesKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Case No. 12, 31 and 50Document5 pagesCase No. 12, 31 and 50Kelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest TaxDocument36 pagesCase Digest TaxKelsey Olivar Mendoza0% (1)

- Case No. 71, 90, 109Document6 pagesCase No. 71, 90, 109Kelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Benin FinalDocument4 pagesBenin FinalKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 11 Tuna Processing Inc. V Phil Kingford & 29 Maniago V CADocument4 pages11 Tuna Processing Inc. V Phil Kingford & 29 Maniago V CAKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- ASEAN Declaration Against Trafficking in Persons Particularly Women and ChildrenDocument2 pagesASEAN Declaration Against Trafficking in Persons Particularly Women and ChildrenKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Civ Case DigestsDocument96 pagesCiv Case DigestsKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 3rd RecitDocument20 pages3rd RecitKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 164 People vs. TrancaDocument3 pages164 People vs. TrancaKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- De Jesus vs. Syquia - Commencement and Termination of Personality (Natural Persons)Document3 pagesDe Jesus vs. Syquia - Commencement and Termination of Personality (Natural Persons)Kelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 9th Civ ch3 ClassworkDocument10 pages9th Civ ch3 ClassworkAdhithyan MNo ratings yet

- Essay Politics HidalgoDocument2 pagesEssay Politics Hidalgojerson hidalgoNo ratings yet

- Consti - CitizenshipDocument193 pagesConsti - CitizenshipAmerigo VespucciNo ratings yet

- Reminder On Political SignsDocument1 pageReminder On Political SignsJude R. SeymourNo ratings yet

- What Is A Political Party?: What Are The Bases For The Formation of Political Parties ?Document2 pagesWhat Is A Political Party?: What Are The Bases For The Formation of Political Parties ?Maryum Chowdhury OrthiNo ratings yet

- Enclosure No. 1 Homeroom Class Organization Elections (MANUAL)Document2 pagesEnclosure No. 1 Homeroom Class Organization Elections (MANUAL)JC LorbisNo ratings yet

- Understanding Thai Politics PDFDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Thai Politics PDFΑνδρέας ΓεωργιάδηςNo ratings yet

- TALAGADocument66 pagesTALAGAChingNo ratings yet

- Representation of People ActDocument17 pagesRepresentation of People ActAnjaliNo ratings yet

- Anthony Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDocument33 pagesAnthony Motion For Preliminary InjunctionKristyn LeonardNo ratings yet

- Democratic Developmental StateDocument11 pagesDemocratic Developmental StateBerihu Asgele Siyum100% (1)

- Local Sectoral Representation, A Legal AnalysisDocument13 pagesLocal Sectoral Representation, A Legal AnalysismageobelynNo ratings yet

- Alliance For Rural and Agrarian Reconstruction, Inc., Also Known As ARARO Party List v. Commission On ElectionsDocument6 pagesAlliance For Rural and Agrarian Reconstruction, Inc., Also Known As ARARO Party List v. Commission On ElectionsThe Supreme Court Public Information OfficeNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 207851 NAVAL VS COMELECDocument18 pagesG.R. No. 207851 NAVAL VS COMELECLou Ann AncaoNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Good Governance On DevelopmentDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Good Governance On DevelopmentumeerzNo ratings yet

- Case Digest CompendiumDocument157 pagesCase Digest Compendiumdodong123No ratings yet

- Regional Trial Court: Hall of Justice, Surigao CityDocument10 pagesRegional Trial Court: Hall of Justice, Surigao CityJf LarongNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument58 pagesDissertationAhsanul HasibNo ratings yet

- Schmitter On DemocratizationDocument13 pagesSchmitter On DemocratizationChristopher NobleNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting Theory 3rd Edition Deegan Test BankDocument35 pagesFinancial Accounting Theory 3rd Edition Deegan Test Banklisadavispaezjwkcbg100% (22)

- Synopsis On Political ScienceDocument4 pagesSynopsis On Political Sciencesiddharth100% (2)

- All About Vote BuyingDocument31 pagesAll About Vote BuyingUPVVotersEducationProgram100% (1)

- Pol GovDocument11 pagesPol GovRomeo Erese IIINo ratings yet

- TOEFL iBT Exam Vocabulary List of 1700 WordsDocument265 pagesTOEFL iBT Exam Vocabulary List of 1700 WordsВиолеттаNo ratings yet

- Rulloda Vs ComelecDocument4 pagesRulloda Vs ComelecZarah MaglinesNo ratings yet

- Letter From Tawi Tawi 1stprize AAraulloDocument18 pagesLetter From Tawi Tawi 1stprize AAraulloedemrjieNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On The Conduct of Certification ElectionDocument27 pagesGuidelines On The Conduct of Certification ElectionDeeby PortacionNo ratings yet

- Hand Book of RO Legislative Council of StatesDocument334 pagesHand Book of RO Legislative Council of StatesDheeraj JainNo ratings yet

- Election RAP NotesDocument8 pagesElection RAP NotesChrizllerNo ratings yet