Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Q1Violin Concerto History-Espen

Uploaded by

lance456Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Q1Violin Concerto History-Espen

Uploaded by

lance456Copyright:

Available Formats

Q1: What composers and concertos do you consider important in this development and why?

Meaning: The development of the violin concerto from the Baroque era until today. Q : !ow has the role of the caden"a changed through the times? #se as many e$amples and dates as you can. Meaning: %mportant colla&orations &etween composers and performers in creating concertos. 'oncerto is a musical composition usually in three or four movements with one solo instrument accompanied &y an orchestra. The term ('oncerto) originally came from %talian* which means to compete or to fight &etween the soloist and the orchestra* the alternation of opposition and cooperation to create the music. %n the si$teenth century* vocal music dominated the musical world+ there were less pure instrumental music. ,lthough much of it appeared in the dance music* it was not played in a significant role. %n the seventeenth century* &el canto occurred in %talian opera* which means that the singer e$pressed personal feelings in a colorful way. The &ac-ground music* orchestra* not only provide harmonic support &ut also supply the volume* and tone quality. The violin stood out all other instruments and soon &ecame the &el canto instrument. The evidence can &e found in the later madrigal &oo-s of Monteverdi. The earliest -nown pu&lication to use the term (concerto) is ,ndrea and .iovanni .a&rieli/s 'oncerti* which the title page of the pu&lication in 1012. The earliest type of purely instrumental concerto is the concerto grosso. The small group of performers* consisting of two violins and &asso continuo* was called concertino 3or trio sonata4. The large group of performers* usually composed in four parts* was called concerto gross. 5ater composers might refer to the larger group of performers as the ripieno* which means a full orchestra* the parts were usually played &y more than one player. 'orelli 31607812174 &rought the form to its first pea- with his

collection of twelve concerto grossi for strings 9p.6 3121:4. These are essentially included the first set of eight da chiesa* which is church music with slow8fast8slow8fast pattern* and the last set of four dance8li-e cham&er music* da camera. Torelli 31601812;<4* concerti musicali 9p.6 316<14* was viewed as the first solo violin concerto regarding to the form and the instrumentation. 9ne is the sequence of three movements in the order fast8slow8fast* and the other is the design of individual movement* especially the opening fast movement. The model came from 9pera. %n most seventeenth8century opera aria* the voice is accompanied &y continuo only and the strophes are separated &y independent orchestra passages &ased on a recurring theme called ritornello. %n the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries* the ritornello was increasingly used &etween phrases of the strophe and even accompanied the voice part. The ritornello form was transplanted into concerto. 9n the other hand* the favored solo instrument in pu&lic performance during 160; was trumpet. Trumpet was sym&oli"ed power and high register sound* and it was usually to &e e$traordinarily s-illed. %f an adequate trumpeter was not availa&le* a violinist might su&stitute 3the trumpet part is mar-ed first trumpet or violin4. %n other words* the composers himself thought such a su&stitution possi&le* this could &e regarded as the &irth of the violin concerto. The first =enetian concerto composer is =ivaldi 31621812:14. !e composed 7; solo violin concertos* introduced the virtuosity into the genre* and was the first to ma-e consistent use of &oth the fast8slow8fast concerto design and ritornello form in the first movements. >econd movements were short and often viewed as a transitional section &etween movements. ?o standard form was devised* and usually &uilt on songli-e. The final movements were similar to the first* &ut in comparison were lighter and playful. %n

violin technique* he used chord with arpeggio in various way* and &ariolage effects li&erally. Many wor-s in the concerto form developed &y Torelli and =ivaldi feature a solo caden"a. 'aden"as were commonly improvised* &ut some were composed and written down. %t usually inserted &efore the &eginning of the final recurrence of the ritornello. !is first printed collection* 5/estro armonico 9p.7 312114* including twelve concertos* arranged in four symmetrical groups* for one* two* and four violins. @or e$ample* ?o.1* A=0 was composed for two violins* and ?o.1;* A=01; was composed

for four violins with cello o&&ligato. B.>.Bach transcri&ed si$ of them for -ey&oard* and latter arranged ?o.1; for four harpsichords and orchestra. =ivaldi/s late concerto is The Cncounter of !armony and %nvention* 9p.1. The first four concertos are his most famous composition* The @our >easons. =ivaldi added sonnets as well as some further instructions in the instrument parts as programmatic guides to each of these four wor-s. Most important among the post8=ivaldian generation of %talian composers is 5ocatelli 316<08126:4. 5ocatelli was the student of 'orelli+ his milestone in the history of violin playing is 9p.7* Twelve violin concertos with twenty8four caden"as 312774* a landmar- in the development of violin technique from 'orelli to the @rench school. The improvised caden"a developed into a self8contained unit within a movement* the term (capriccio) was gradually adopted for it. The standard of these twenty8four (capriccio) is similar to latter Daganini/s tremendous wor-* twenty8four capriccios. B.>. Bach composed two solo violin concertos in , minor 3BW= 1;:14 and C maEor 3BW= 1;: 4* and one dou&le concerto in F minor 3BW= 1;:74. >olo violin concertos pro&a&ly written for the 'othen court/s star violinist* Bosephus >piess. ,ll pieces are clearly inspired &y =ivaldi* &ut the relationship &etween solo and tutti &ecomes

more comple$. Both may &e com&ined in any given section of the ritornello design. 9ne more important wor- composed during 'othen period is the Branden&urg 'oncertos 3BW= 1;:681;014 in 12 1. Bach dedicated the collection to the Margrave of Branden&urg* Eust a few days after his thirty8si$th &irthday. These wor-s reflect the splendor of the 'othen court+ Bach grouped the pieces together* &ut never designed to &e performed as a cycle. ?o. 1 3 horns* 7 o&oes* &assoon* violin piccolo* and a string quartet and &asso continuo4 is the only movement included seven movements. ?o. 3trumpet* recorder* o&oe* solo violin and a ripieno string orchestra with continuo.4 ?o.7 37 violins* 7 violas* 7 cellos* continuo and &ass.4 ?o.: 3 recorders* solo violin* and a ripieno string with continuo.4 ?o.0 3solo violin* solo flute* solo harpsichord* and a string ripieno and &ass.4 ?o.6 3 viola da &raccios* viola da gam&a* cello and continuo8&ass

and harpsichord.4 %n the wor- ?o.0* the harpsichord ta-es a significant step forward on its path to &ecome a maEor solo instrument. %n the later year date from 5eip"ig* Bach composed numerous harpsichord concertos. >ince the harpsichord traditionally had &een viewed as a continuo or unaccompanied solo instrument* Bach had no direct models to follow as had in the violin concertos* although his fascination with counterpoint as a -ey&oard performer. !e adopted and arranged his earlier concertos for the violin or other instruments to the -ey&oard idiom. Bach/s three surviving violin concertos and Branden&urg 'oncerto ?o.:* which features the solo violin* form the &asis of four of the harpsichord concertos. By the year Bach died in 120;* the solo concerto had replaced the concerto grosso* a genre especially popular in Daris in the 122;s. Wor-s were written virtually for each orchestral instrument in the solo role* although the violin remained the favorite.

'ello was growing to &ecome a solo instrument* &ut the repertory was small. The very first two cello concertos composed &y !aydn 3127 811;<4* which were ?o.1 in ' maEor* and ?o. in F maEor. Both are the cellist/s standard repertory for today. Cventually* a nonorchestral instrument* the harpsichord* and later* the newer pianoforte* &ecame the most popular choice. There are some reasons: first of all* the sound of -ey&oard instrument* particularly the hammered strings of the piano* contrasts strongly with that of the orchestra. >econdly* it is the only instrument capa&le of matching the orchestra in range* the fullness of sound. Third* it is capa&le of accompanying itself. %n other words* it can play melody and provide its own harmonic support* and it could &e used alone to create a stri-ing contrast with the orchestra. %n the classical period* the composers were often great -ey&oard artists* and wrote concertos for their own use. 9n the other hand* the orchestra gradually e$panded in si"e and more regularly included winds and percussion. Gey&oard instrument was used in e$tremely effective way for composers to counter&alance increasingly virtuosic solo writing. Mo"art 31206812<14 composed piano concertos &efore writing violin concertos. !e was influence &y B.'.Bach 312708121 4 to create a concerto8sonata form* which is given an equal role &etween solo and tutti* while he calls for a lively give8and8ta-e cooperation of the force* and in galant style. %n 1220* Mo"art turned attention to compose violin concertos. !e composed five violin concertos* ?o. 1 in B8flat moaEor* -. ;2* ?o. in F maEor* -. 11* ?o.7 in . maEor* -. 16* ?o.: in F maEor* -. 11* and ?o.0 in , maEor* -. 1<* all were &orn in the same year. These wor-s follow the same &asic pattern* with concerto8sonata first movement* arioso or cantilena slow movement in the dominant and rondo finales. C$cept for the ?o.1* all are written in -eys that sound good on the violin*

ma-ing use of the sympathetic vi&ration of open strings that also favor the sound of certain dou&le stops and chords. The caden"a is followed the traditional design* which is immediately &efore the orchestral conclusion* at the point where the orchestra had reached a second version of tonic chord that normally would resolve* &y way of the dominant* to the tonic. >imilar to &aroque style* composers left the space for performers to improvise. Beethoven/s violin concerto in F maEor* 9p.61 was composed a violinst* @ran" 'lement* in 11;6. The premiere was rough since on the program+ 'lement was not only playing Beethoven/s piece* &ut also playing a sonata on one string while holding the violin upside8down. The pu&lic was admired more on 'lement/s circusli-e interpretation rather on Beethoven/s violin concerto. ,fter thirty8five years* Balliot revived it and gave it first performance successfully in Daris in 11: * played &y a 1 8year8old violinist Boseph Boachim with orchestra conducted &y Mendelssohn. Derhaps duo to the lac- of success at its premiere* and the request of Mu"io 'lementi* Beethoven arranged the wor- for piano version and composed the caden"a. Based on his piano caden"a* a num&er of later composers have &een made to derive from it to violin concerto. =ieu$temps 311 ;811114 was the first to do this. Many violin virtuosos have provided their own caden"as* those &y Boachim and Greisler have &ecome &est -nown. Both of them were composed caden"a for Mo"art/s violin concertos. >imilar to Mo"art* Beethoven composed piano concertos &efore writing violin concerto. 'ompare to his dramatic symphony8li-e piano concerto* Beethoven/s violin concerto is more lyrical* songli-e quality. !e was familiar with several leading figures of @rench >chool violinists* such as =iotti 31200811 04* Aode 3122:8117;4* and Greut"er* Beethoven &orrowed inspired idiomatic features of @rench violin music to achieve new generation of violin concerto. @irst of all* Beethoven used

high register in solo violin part to stand out from the orchestra* and the use of shoc-ing harmonic shifts. >econdly* the unusual treatment of solo trills. Beethoven uses these trills not only to end a section* &ut also to launch e$tensions to solo section. Third* the solo violin introduced the new idea in the development accompanied &y orchestra without ritornello. @inally* the solo violin appeared in the coda following the caden"a. These characters made violin concerto in the nineteenth century &ecomes virtuoso. @ollowing Beethoven/s lead* composers of nineteenth century introduced the heroic figure. Many composers discarded the old ritornello form* and increasingly wrote the caden"a instead of relying on the solo performer to improvise. They could control the most virtuosic element if the materials were written down. The solo violin presented thematic material and virtuoso figuration while accompanying the orchestra during its presentation of thematic material. The slow movement tended to &e short* viewed as introduction to the fast and highly virtuosic finales. 'omposers often lin-ed the slow movement to the finale without pause* and the final movements had always &een the most &rilliant in a concerto. 'aden"a used to &e placed &efore the orchestral conclusion* in the nineteenth century+ composers e$perimented with placing the caden"a in a variety of places in the movement* usually integrating the traditional moment for intense virtuoso display into the wor-/s larger form. >ome composers even e$perimented with accompanied caden"a. @urthermore* the relationship &etween composers and performers &ecomes closed. 'omposers respected the performers* and intended to discuss together and cooperated a virtuosic wor-. Mendelssohn 311;<811:24 violin concerto in C minor* 9p.6: 311718::4 is an e$ample of to start the custom. The violin concerto was written for the violinist @erdinand Favid. %n 1171* Mendelssohn wrote Favid a letter* and mentioned

an interest in composing a concerto* and the idea was already ta-ing shape in C minor. Favid helped with minor revisions and was largely responsi&le for the content of the caden"a. The formal innovation is significant. @irst of all* the entrance of the soloist is in the second &ar. Mendelssohn too- out the traditional ritornello form and stated the main theme alone shortly &y soloist and the orchestra played the theme thereafter. %n the second theme* the orchestra first presents the melody accompanied &y soloist while the soloist plays on a sustained open .8note. >econdly* the central placement of the caden"a &ecomes the development of the sonata form* and connected to the recapitulation* which the orchestra presents the main theme and accompanied &y soloist. @inally* it is a through8composed concerto. There is a sustained &assoon note to lin- the first and second movement* and &efore the finale* there is a recitative8li-e passage of fourteen measures without pause. Mendelssohn/s influence successfully made the important effect to the ne$t generation. Favid/ student* Boseph Boachim* was not only a fantastic violinist &ut also had close friendship with several master composers. ,fter he played Beethoven/s violin concerto successfully* composers such as >chumann 3111;811064* Brahms 31177811<24* and intended to write the violin concerto for him. >chumann heard Boachim played Beethoven/s violin concerto of the second time and met with him after the concert. Boachim was complaining a&out the empty virtuosic repertorie* and >chumann responded &y composing the @antasie in ' maEor* 9p.171 311074 and invited him to play. %t is a &rilliant one8movement piece in sonata8allegro form with a slow introduction. ,fter completing the @antasie* >chumann &egan the composition of a more 'lassically structured wor- for Boachim* =iolin 'oncerto in F Minor 311074. Boachim was not happy

with the piece* and complained that it was too much repetition* especially in the final movement* there was no sufficiently idiomatic or &rilliant to satisfy a violinist. %t gave an impression of having &een written with the piano in mind* rather than the violin. The solo part is often covered &y the orchestra and not sufficiently differed from it. Dro&a&ly Boachim was getting proud* he as-ed Brahms to write a violin concert for him. Before the violin concerto composition* Boachim was helping some of Brahms/s piano concertos and symphonies. ,s a violinist and conductor* Boachim indeed proved a relia&le and ready source of information for Brahms. Brahms =iolin 'oncerto in F maEor* 9p.22 311214 modeled some e$tent on Beethoven/s =iolin 'oncerto* ritornello form stated in the orchestra &ut fantasia8li-e in the soloist. The second movement features a solo o&oe e$pressive melody. 'uriously* this melody is never given in its entirety to the soloist. The finale is a rondo with strong !ungarian or gypsy element especially included to please Boachim who was &orn in !ungary. Fvora-/s violin concerto in , minor 9p.07 3112<4 was originally written for Boachim. When Fvora- finished the composition and presented to Boachim. ,s a violinist* Boachim disli-ed several passages* &ut never said anything to Fvora-* instead* he claimed to &e editing the solo part. @inally* he never actually performed the piece* although the piece was dedicated to him. Fvora-/s violin concerto is lyrical* &old* and filled with fol-8inspired melodic ideas characteri"ed &y strong rhythms. There is no caden"a written in the piece* and the first two movements are lin-ed together. The second movement is a Fum-a* a -ind of lament in moderate duple meter of Bohemian fol- dance. Fvora-/s '"ech fol- music is a significant impression in the nineteenth century. Many sets of variations and fantasies are &ased on fol- tunes. %t is a reflection of

century/s intense interest in nationalism* which included the musical past of one/s own people. 5alo/s >ymphonie Cspagnole 311204 was written for solo violin and orchestra* dedicated to >arasate. There are five movements* including >panish >eguidilla* a flamenco dance* and Malaguena* a form of the fast* triple8meter fandango. >aint8>aens/s violin concerto ?o.7 in B minor* 9p.61 3111;4 is not >panish music. There is a graceful fluid &arcarole styled in the second movement* and another chorale8style passage sounding li-e Wagner in the finale. Tchai-ovs-y 311:;811<74/s =iolin 'oncerto in F maEor* 9p.70 311214 was inspired &y 5alo/s >ymphonie Cspagnole. %n 1121* Tchai-ovs-y was recovering from the &rea-down of his marriage and his su&sequent suicide attempt in >wit"erland. !is favorite student 3possi&ly his lover4* the violinist Boseph Bosefovich Gote- 31100811104* who was studied with Boachim* shortly visited him with some new music. 9ne of them is 5alo/s >ymphonie Cspagnole. Gotet assisted with violin technique issue in the writing of solo part* and Tchai-ovs-y originally wanted to dedicate to him. Dro&a&ly he felt constrained &y the gossip this world undou&tedly causes a&out the true nature of his relationship with the younger man. %n 1111* he &ro-e up with Gotet after he refused to play the concerto+ Tchai-ovs-y changed his mind to as- 5eopold ,uer 311:081<7;4. ,uer reEected him since he thought the piece was too difficult and too modern* finally* he found the soloist* ,dolph Brods-y* playing in the first performance in 1111. Tchai-ovs-y modeled Mendelssohn/s violin concerto* such as the placement of the caden"a at the end of the development and its overlap with orchestra/s start of the recapitulation. %n the nineteenth century* &esides some composers were cultivated traditional musical value and introduced nationalistic concertos a&ove* others were contri&uted the

virtuosic wor- which means violinists8composers. Daganini 3121 811:;4/s concertos were largely influenced &y mem&ers of @rench violin school: =iotti* Greut"er* and Aode. !e wrote si$ violin concertos* and the technique and the music were com&ined with characters of %talian composers. !e used the 'lassical concerto8sonata form with full orchestral ritornello* and did not see- new forms or novel methods of organi"ation. %nstead* his innovations focused on the development of violin technique* and he gave virtuosity new musical meaning. 'aden"as usually are placed to interrupt the final ritornello. @or the most part* Daganini improvised his caden"as. %n violin technique* there are several unusual device: 14 >cordatura. 4 !armonics* including natural and artificial harmonics* and introduced dou&le8stop harmonics. 74 5eft hand pi""icato* and wide intervals. ,fter Daganini* two leading violinist8composers followed Daganini and &rought new life to the @rench violin school: =ieu$temps and Wieniaws-i. , num&er of contrasting factors have affected development in violin music since 1<;;. ?ot only nationalistic element* &ut also traditions of the classic8romantic era continued to &e o&served+ classicism was seen chiefly in formal aspects* while highly chromatic writing echoed nineteenth8century romanticism. The method developed and practiced &y >choen&erg and mem&ers of his school* composing with twelve tones related only to each other* which amounted to an e$treme departure from traditional views of harmony. The concept of a row* or series* of tones* of series music* was then applied to other musical elements* especially rhythm* dynamics* and tim&re. 9ther factors that affected early twentieth8century developments came from fol- music* especially from the Western Curope* which was &ased on rhythms and scales quite apart from the Western maEor8minor tradition. , renewed interest in older music proved itself late in the

century* evidence can &e found in the cultivation of forms from the &aroque and earlier period. Clgar =iolin 'oncerto in B minor* 9p.61 31<;<81;4 was dedicated to violinist Greisler. ,ctually Greisler as-ed Clgar to write the concerto since Greisler admired Clgar/s The Fream of .erontius* 9p.71 31<;;4* a wor- for voice and orchestra. >imilar to Beethoven or Brahms/s concerto* Clgar/s is in the standard three8movement sequence of fast8slow8fast* especially longest in the finale. The second movement &egins in the remote -ey of B8flat maEor. The orchestra sings the flowing main theme* which reminds some of the slow movement of Brahms/s violin concerto. The finale returned &ac- to B minor* then thematic transformation to B maEor. The caden"a is placed on the finale* which is accompanied &y the orchestral strings using a new technique* pi""icato tremolando* a -ind of dramatic strumming made &y &rushing the strings with the soft tips of three or four fingers. Derhaps this is meant to imitate >panish guitar music* alluding to the >panish inscription at the &eginning of the score. @inland composer >i&elius 3116081<024 =iolin 'oncerto in F minor* 9p.:2 31<;74 originally for Willy Burmester* a concertmaster of the !elsin-i 9rchestra in the 11<;s. !owever* >i&elius wished to perform earlier than he planed* Burmester could not find the time to prepare it. The other violinist* =itor ?ovace- performed it in 1<;:* and he thought the wor- were too difficult. 9nce Burmester found time to wor- on it* he thought difficult too* and as-ed >i&elius to revise. @inally* >i&elius revised several difficult places in 1<;0 and performed under the direction of Aichard >trauss and Garl !alir was the soloist. The wor- is in the standard three movements* clearly separately &y pauses and without any thematic connection. >imilar to Mendelssohn/s violin concerto*

the soloist entered in the fourth measure to present the main theme without orchestral ritornello* and e$tended caden"a for soloist to ta-e on the role of the development section in the sonata form. >travins-y 3111 81<214 composed ten concertos or concerto8li-e wor-s in neo8 'lassical style. 9ne of them is =iolin 'oncerto in F maEor 31<714* dedicated for young ,merican violinist* >amuel Fush-in* a request from his pu&lisher. >travins-y started a particularly widely spaced chord at the &eginning of each movement. The =iolin 'oncerto has four movements* all with Baroque titles: Toccata* ,ria %* ,ria %%* and 'apriccio. %n &aroque period* the term toccata referred to a style of virtuoso -ey&oard composition. ,dapting the style to violin* >travins-y developed his own version of &ro-en8chord figuration and a -ind of &ariolage technique characteristic of Baroque violin concertos. Toccata also referred to processional fanfare for trumpets and timpani* so that >travins-y/s main theme* presented in trumpets* may have &een inspired &y this form of the toccata. The middle aria movements used the traditional Baroque da capo aria in which the solo singer em&ellished the first portion of the aria upon its repeat at the conclusion. The finale was inspired &y Bach/s dou&le violins concerto* in F minor. !e used a solo violin from orchestra to against the soloist as a duet accompanied &y orchestra. Besides >travins-y* there are two other important composers came from Aussia* Dro-ofiev and >hosta-ovich. Both of them were writing two violin concertos. >hosta-ovich/s concertos were dedicated to Favid 9istra-h. Tal-ing a&out neo8'lassicism* no one can forget to mention to >erialism. %n 1< ;* >choen&erg 3112:81<014 developed the twelve8tone technique* a widely influential compositional method of manipulating an ordered series of all twelve notes in the

chromatic scale. Fue to escape the ?a"i* >choen&erg moved to #nited >tate in 1<77. The violin concerto 31<7:4 was the one of his first ,merican wor-* composed during a period of great loneliness and deEection. The wor- is >choen&erg/s earliest compositions in concerto form adapted the wor- from eighteenth8century composer. The reflection of >choen&erg/s connection with neo8'lassicism* which turned to use classical form* and tonal writing* is different with >travins-y/s neo8'lassical style. >choen&erg was still using twelve8tone technique. The solo violin part is very difficult* including large intervals such as triple and quadruple stops* unrelia&le harmonics in dou&le stops* and left hand pi""icato. These technique characters are nearly e$ploitation of the instrument/s e$treme range. The piece was dedicated to his student* We&ern. Berg 3111081<704 was the other student of >choen&erg. 'ompare to >choen&erg+ Berg/s music is more tonality* although &oth are atonal composers. Berg/s violin concerto 31<704 was his last wor-. Berg received a commission from the ,merican violinist 5ouis Grasner* who played >choen&erg/s violin concerto in the first performance. The piece was dedicated (To the Memory of an ,ngel*) to Mahler/s daughter* ,lma. %t structured in two movements and each further divided into two sections: first movement is in classical sonata form* second movement is a dance8li-e section* third movement is a caden"a8li-e* &ased on a single recurring rhythmic cell* and an ,dagio fourth movement. There is no pause &etween first and second movements* and as same as third and fourth movement. Berg used twelve8tone technique* &ut the series of pitches he chose &asis possesses string tonal tendencies: .* B8flat* F* @8sharp* ,* '* C* .8>harp* B* '8sharp* C8flat* @ %n the music content* Berg quoted tonal materials including fol- song* 'arinthian in

>outh ,ustina* and 'horale tune from B.>.Bach Hs 'antata ?o.6;. Barto- 3111181<:04 was not >erialism composer. %nstead* he &egan to collect folsongs in the countryside* developing a great sensitivity to and understanding of folmusic in 1<;:. %n 1<;1* his fol-loric elements &ecame his important character. Bartowrote two concertos. ?o.1 31<;28;14 was written at the time fol-loric character &ecame solid. The piece was dedicated to >tefi .eyer* a !ungarian violinist with whom he was in love. Barto-/s second violin concerto 31<728714 was the last concerto &efore he moved to #nited >tate in 1<:;. , violin virtuoso* Ioltan >"e-ely* requested the wor- in 1<76. Furing composing the piece* he was in a difficult life situation filled with serious concern a&out the growing strength of fascism. Barto- wished to write a single8movement theme and variations* &ut >"e-ely wanted a standard three8movement concerto. %n the end* they compromised to have a three8movement variations piece. !indemith 311<081<674 has no interest for twelve8tone music or atonality+ his music is always tonal &ut developed some unique theories of pitch and interval relationship &ased on overtone series* and neo8'lassical style. The violin concerto 31<7<4 was the last concerto of !indemith/s &efore moving to #nited >tate in duo to ?a"i. !indemith/s typical preference for the winds ma-es for strong contrast* especially when the &rass instruments are given the responsi&ility for maEor clima$. There is an e$tensive caden"a for the violin occurs near the end of the final movement.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Berklee Online - Songwriting Handbook PDFDocument29 pagesBerklee Online - Songwriting Handbook PDFfinaldrumgod100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Philip-Tagg PDFDocument550 pagesPhilip-Tagg PDFMiguel Ángel Gálvez Fernández100% (1)

- Horowitz Carmen Variations (Jeffery 1968 Version)Document9 pagesHorowitz Carmen Variations (Jeffery 1968 Version)The Enigma of Sphinx100% (1)

- George Enescu Op11 2 Romanian Rhapsodies-1 PianoDocument20 pagesGeorge Enescu Op11 2 Romanian Rhapsodies-1 PianoEljona BodeNo ratings yet

- Shostakovich - Piano Sonatas & PreludesDocument22 pagesShostakovich - Piano Sonatas & PreludesWilson Silva Amorim67% (3)

- Style Sheet #1 - Der Kuss BeethovenDocument2 pagesStyle Sheet #1 - Der Kuss BeethovenShubhangi DasNo ratings yet

- Champions League Theme, Easy Piano VersionDocument1 pageChampions League Theme, Easy Piano VersionJulie G. MusicNo ratings yet

- Chopin - Nocturne Op9, No2 Sheet Music For PianoDocument1 pageChopin - Nocturne Op9, No2 Sheet Music For PianoNi Luh AyusthaNo ratings yet

- Apple Garage BandDocument22 pagesApple Garage BandFoxman2k100% (1)

- Gustav Anderson's "You Are My SunshineDocument2 pagesGustav Anderson's "You Are My Sunshinelance456No ratings yet

- Introduction To Music: Year 7 - Autumn 1Document69 pagesIntroduction To Music: Year 7 - Autumn 1lance456No ratings yet

- 1.12 C and F NaturalDocument17 pages1.12 C and F Naturallance456No ratings yet

- Maple Leaf RagDocument1 pageMaple Leaf Raglance456No ratings yet

- Apple Garage BandDocument22 pagesApple Garage BandFoxman2k100% (1)

- Grand Staff Note Name Speed Test C 100 Notes - MusDocument1 pageGrand Staff Note Name Speed Test C 100 Notes - Musjhbella0% (1)

- All Student Instruments (Rentals & Sales) Are Professionally Set Up, With Top Quality SoundDocument3 pagesAll Student Instruments (Rentals & Sales) Are Professionally Set Up, With Top Quality Soundlance456No ratings yet

- Complete Theory TextDocument113 pagesComplete Theory Textlance456No ratings yet

- Worksheet 0028 Bar Lines and BeatsDocument1 pageWorksheet 0028 Bar Lines and Beatslance456No ratings yet

- Maple Leaf RagDocument1 pageMaple Leaf Raglance456No ratings yet

- Complete Theory TextDocument113 pagesComplete Theory Textlance456No ratings yet

- Apple Garage BandDocument22 pagesApple Garage BandFoxman2k100% (1)

- 2012 10 006 Lights and Marvels EngDocument2 pages2012 10 006 Lights and Marvels Englance456No ratings yet

- 1.00 First Year Long Range Plan-2Document5 pages1.00 First Year Long Range Plan-2lance456No ratings yet

- Essential Music Vocabulary ReviewDocument56 pagesEssential Music Vocabulary Reviewlance456No ratings yet

- Gustav Anderson's "You Are My SunshineDocument2 pagesGustav Anderson's "You Are My Sunshinelance456No ratings yet

- The EtudeDocument445 pagesThe Etudelance456No ratings yet

- IMSLP14478-Schubert Erlkonig Arr - Ernst Violin SoloDocument6 pagesIMSLP14478-Schubert Erlkonig Arr - Ernst Violin SolotausigalkanNo ratings yet

- Essential Music Vocabulary ReviewDocument56 pagesEssential Music Vocabulary Reviewlance456No ratings yet

- Music theory notes: A guide to reading musicDocument3 pagesMusic theory notes: A guide to reading musiclance456No ratings yet

- Music theory notes: A guide to reading musicDocument3 pagesMusic theory notes: A guide to reading musiclance456No ratings yet

- 14-15 Children's VLN2Document35 pages14-15 Children's VLN2lance456No ratings yet

- (Free Com Tchaikovsky Piotr Ilitch Violin Concerto Major All Three Movements Mv1 SoloDocument14 pages(Free Com Tchaikovsky Piotr Ilitch Violin Concerto Major All Three Movements Mv1 SoloVictor FloresNo ratings yet

- Ravel Divisis: in 2-Inside/outside in 3 - by Stand in 4 - by PersonDocument1 pageRavel Divisis: in 2-Inside/outside in 3 - by Stand in 4 - by Personlance456No ratings yet

- 0106 ClinicDocument2 pages0106 Cliniclance456No ratings yet

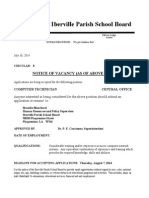

- Computer Technician 073014Document2 pagesComputer Technician 073014lance456No ratings yet

- The Contemporary Contrabass. by Bertram TuretzkyDocument5 pagesThe Contemporary Contrabass. by Bertram TuretzkydoublepazzNo ratings yet

- Week 1: Third Quarter-Music 9Document3 pagesWeek 1: Third Quarter-Music 9Catherine Sagario Oliquino0% (1)

- Composer Cereal Box Project GuideDocument3 pagesComposer Cereal Box Project GuideSandi BerginNo ratings yet

- Hypermodes - A Practical GuideDocument268 pagesHypermodes - A Practical GuideLeonel RasjidoNo ratings yet

- Grieg Dance of Anitra Guitar FluteDocument4 pagesGrieg Dance of Anitra Guitar Fluteabetmesa100% (1)

- Swordfish - 03 - Violin IIDocument2 pagesSwordfish - 03 - Violin IIEthan WindleNo ratings yet

- Just The Two of Us: by Bill Withers, Ralph Macdonald, William Salter Arranged by Nicholas CoccoDocument2 pagesJust The Two of Us: by Bill Withers, Ralph Macdonald, William Salter Arranged by Nicholas CoccoCarlão Musico100% (1)

- Arran, John - Technical Hangups - Prelude 1 Villa-Lobos (Guitar Feb 84)Document1 pageArran, John - Technical Hangups - Prelude 1 Villa-Lobos (Guitar Feb 84)Yip AlexNo ratings yet

- FENAROLI Partimenti - Teoria PDFDocument94 pagesFENAROLI Partimenti - Teoria PDFFabioCuccu100% (1)

- Kaval Sviri Simile-Violin 2Document1 pageKaval Sviri Simile-Violin 2Mark ScottNo ratings yet

- Liquidation, Augmentation, and Brahms's Recapitulatory OverlapsDocument26 pagesLiquidation, Augmentation, and Brahms's Recapitulatory OverlapsssiiuullLL100% (1)

- University of Texas PressDocument17 pagesUniversity of Texas PressNoor Habib Sh.No ratings yet

- Trumpet Concert Band ScalesDocument3 pagesTrumpet Concert Band ScalesMarcos César VianaNo ratings yet

- The Basic CarusoDocument3 pagesThe Basic CarusoHigh ManwichNo ratings yet

- ONCE and Again, Evolution of A Legendary FestivalDocument57 pagesONCE and Again, Evolution of A Legendary FestivalManuel Alfredo Ayulo RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Sway Latin Alto Sax Solo For Big Band-PartsDocument57 pagesSway Latin Alto Sax Solo For Big Band-PartsChristopher Becker100% (2)

- Dvorak Largofromthe New World SymphonyDocument8 pagesDvorak Largofromthe New World SymphonyAudrey WalterNo ratings yet

- Jorge-Ojeda-Munoz-Final-Paper RevisedDocument8 pagesJorge-Ojeda-Munoz-Final-Paper RevisedJörge Daviid ÖjedaNo ratings yet

- MATRIX GR 1 10 MAPEH Curr Implementation and Delivery MGNTDocument135 pagesMATRIX GR 1 10 MAPEH Curr Implementation and Delivery MGNTClarkNo ratings yet

- 10 Jazz BluesDocument4 pages10 Jazz BluesAnonymous 26kU5IvyKS100% (4)

- Musical Scales of The WorldDocument267 pagesMusical Scales of The WorldNathan Breedlove100% (11)

- Music 10-Q1-LasDocument3 pagesMusic 10-Q1-LasNorham AzurinNo ratings yet

- A2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document12 pagesA2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungNo ratings yet

- 20th-Century Guitar Author Mary CriswickDocument2 pages20th-Century Guitar Author Mary CriswickSergio Calero FernándezNo ratings yet