Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Looking Back Issue 4

Uploaded by

Julian HornCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Looking Back Issue 4

Uploaded by

Julian HornCopyright:

Available Formats

Issue No.

4 November 2009 PLU: 21872

ISSUE 4 - Moments in Time

1.50

Only available from

As I was preparing to put this issue together, Mrs Ruth Dwornik got in touch because she is preparing to move and had come across some olf negatives and asked if I would like to look after them! As a result, most of the other material has been put to one side and half this issue is the result of Ruths generosity. I am also delighted to have some colour now, for as glance below will show you; history isnt always 100 years ago and isnt always in black and white!

Contents . . .

Scenes from the 1963 Carnival .......................... Page 2 & 3 John Pory - A Thompson man ........................... Page 4 The LDV from Deric Waters ............................... Page 5 A family of Watton in 1907 but who & where? . Page 6 Loch Neaton - 17th May 1948 ............................ Page 8 More Schooldays - from the late 1930s ........... Page 9 A day in the Life of Watton in the 70s ............. Page 10 The Doomed Squadron ...................................... Page 12

Edwards

High Street Watton

At the History of Watton and Wayland

1963 Carnival

In 1963 colour film, because of the cost was reserved for quite special occasions, and there was no more suc special occasion for Watton in 1963 than the Crowning of the Carnival Queen which took place on Monday June 17th at 7pm in the Market Place, and was conducted by a Norwich City Footballer. The Carnival Queen was Miss Sheila Campbell from RAF Watton, and her Attendants were (on our left in the pictures) Miss Ann Barnard and (right) Miss Margaret Reynolds. The Lord Mayor was Mr Freddie Archer and the Court Jester was Mr Chris Levy. There are more pictures inside on pages 2 and 3.

Abels Wednesday Auction 1989

The three pictures on the left are from a few slides which have been identified (from the calendar on the wall in the office) as being from 1989. Extreme left is viewing in the main saleroom, middle is the Auctioneer Noel Abel selling the outside lots and on the adjacent left Marie Woodyatt (furthest) and another I don't know in the office taking the payments and paying vendors too. Note the early computer!

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 2

Scenes from the1963 Carnival

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 3

A winded Teddy Savory gets some medical attention

Some pictures from the Fancy Dress Dance. Above: Dressed up as characters from the Mad Hatters Tea Party and having a turn around the floor of the Queens Hall are Mr and Mrs Ernie Edwards. Left seated furthest back are Michael and Dulcie Adcock and I think Mrs greenwood on our right. Above right is I think Mr Brian Sharman and Mr & Mrs Shepherd-Page - I don't have any clues on the person in the hat. Last Who are Fred and Wilma or is that Barney and Betty? All suggestions gratefully received!

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 4

JOHN PORY - A THOMPSON MAN AT THE FOREFRONT OF NEW GOVERNMENT IN VIRGINIA

By Bronwyn Tyler

We have all grown up with stories of the Mayflower, which set sail on 16th September 1620, bound for New England with many Norfolk folk on board. Equally most people will have heard of John Rolfe and his marriage to Pocahontas; or perhaps of John Smith, saved from death at the hands of her own people by Pocahontas. But, have you heard of a man called John Pory, a contemporary of the above and a local man, who achieved as much, if not more? His story is possibly even more fascinating than any of theirs. John Pory was born in Thompson in 1572. He and his twin sister Mary were christened in St Martin's Church, Thompson on March 16th of the same year. Their father, William, was last in a long line of wealthy tenants whose family home was Butters Hall or Boutetort Hall, one of the manors of Thompson, which unfortunately no longer exists. The Porys were not only wealthy but also an influential family whose origins seem to have been in Sutton St Edmunds in Lincolnshire. An exhaustive history of John Pory has been written by Professor William Powell of North Carolina University and I am very grateful for his permission to use his work as my main source for this article, which can only be a brief outline of a very adventurous life. The Pory family were well educated; an earlier John Pory was Master of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and counted the then Archbishop of Canterbury among his friends. When our John was sixteen he entered Gonville and Caius College Cambridge. In 1592 Pory gained his Bachelor of Arts degree and obtained his masters in 1595. He earned a reputation for his skill in modern languages, particularly French and Italian. After gaining his masters he remained at his college as an instructor in Greek. He was also very skilled in Latin. In 1597 Pory began an association with Reverend Richard Hakluyt, rector of Wetheringsett in Suffolk where it appears he was being trained as Hakluyt's successor in the study of cosmography and history. Hakluyt had built up quite a reputation as a collector and publisher of travel accounts. Pory not only assisted in the publication of many of the works but also used his language skills to translate a number, including one entitled 'A Geographical Historie of Africa Written in Arabicke and Italian by John Leo', which earned him much praise and remained a standard work on Africa until the early nineteenth century. The editors of the Oxford English Dictionary also credit Pory with the earliest use of words such as hippopotamus, zebra and many others. It seems only natural that John Pory's knowledge of other countries, even though he had never actually visited any of them, should lead him to develop an interest in the opening up of the New World. The new colony in Virginia had been founded in 1607 and one of the first letters to be brought back was one addressed by a Dutchman to John Pory. One of the early settlers was a Peter Pory, quite possibly a relative. By 1609 a second charter had been granted to the Virginia Company (full title of the corporation: 'The Treasurer and Company of Adventurers and Planters of the City of London for the First Colony in Virginia') and John Pory was listed as one of the grantees. It seems John Pory was no longer content to be a writer and translator because by 1605 he had a new career; he was elected as Member of Parliament for Bridgewater in Somerset. He held this position until 1611 when Parliament was dissolved. It was a difficult time between king and Parliament, requiring much negotiation, which was to stand Pory in good stead later. At the end of this period of Parliament, Pory was granted a licence to travel by the king. (In those days permission had to be obtained from the king to leave the country.) The majority of his journeys were on government business; first to Ireland and then to France. In 1613 he moved on to Padua and Turin in Italy and from there he went to Constantinople (Istanbul) where he was attached to the embassy of Paul Pindar of the Levant Company. Although kept busy with the affairs of the company and its extensive trade, John still had time to work on his translations; this time a book by King James from French into Italian. By January 1617 he was back in England, reporting on the affairs of the company to the government. Pory was considered for the post of secretary to the Ambassador in The Hague, although there were some reservations because he was said to be too fond of the drink. He did visit the Hague briefly and on his return to England was sent on a mission to the Continent to search for the missing grandson of Thomas Cecil, Earl of Exeter. He was unsuccessful. Back home once more he seems to have been offered an embassy post in The Hague but for some reason he declined. Although John Pory seems to have wandered about, moving from job to job and in constant search for meaningful employment, his main means of earning money throughout his life was as a professional newsletter writer. There were no newspapers in those days as we know them. Wealthy men, who often had to leave London on business or to care for their country estates, were keen to keep in touch with affairs of court and city gossip. A man in Pory's position was an ideal correspondent and his writing skills added to the popularity of his newsletters. His writing was not all dull political and court news; Pory had a keen sense of humour and was fond of an amusing story. He covered an enormous range of topics, just as newspapers do today. Such was the professionalism of the men of letters writing at this time that they set the scene for the creation of the printed newspaper in England. In the United States Pory is hailed as the father of newspapers. One of Pory's most interesting letters is his detailed account of the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh which he sent to Sir Dudley Carleton in 1618. It was in 1618 that John Pory's life was to take a new turn. In December he was made Secretary to the new Governor of Virginia, Sir George Yeardley. Yeardley was married to John Pory's first cousin, Temperance Flowerdew. A friend commented that an additional benefit to the financial reward and prestige of such an office was that there was little opportunity for him to obtain alcohol there and he would therefore become a 'sufficient sober man'! John Pory left England with the Governor and his wife on January 19th 1619 and arrived in Jamestown on April 18th. Pory's official duties were mainly in Jamestown but he was also required to visit other settlements. He also chose to explore Virginia for himself and wrote copiously about the mineral resources, flora and fauna. He was enthusiastic about the opportunities to develop this new country. The prime purpose of the new Governor and his staff was to move the colony forward, from being run as a company towards popular government. The colony needed better organisation and laws. An annual Assembly was to be held, attended by two freely elected burgesses from each plantation. Martial law was abolished and English Common Law established. Instructions for the setting up of a legislature were sent over by the government with Yeardley. Thus it was that the first Legislative Assembly in Virginia took place in the choir of the church in Jamestown on July 30th 1619. The four members of the 'Counsell of Estate' were the Reverend Samuel Macocke, John Pory, Nathaniel Powell and John Rolfe. In addition there were twenty two burgesses. John Pory was elected Speaker, a position similar to that of Speaker of the House of Commons. It is clear that John Pory's experience as an MP, a government agent and an observer of political life had proved good training for this important role. The business of government in this remote place was conducted just as it would have been in London and each bill or matter to be discussed was dealt with following parliamentary procedure. This included the creation of two standing committees. The term of Pory's office was three years. After this he was free to extend his explorations before returning to England, incidentally aboard a ship captained by the man who had captained the Mayflower. His journey included a visit to New England but became more memorable when he was shipwrecked off the Azores in a storm. The Portuguese officials of the islands arrested him for piracy and he was due to be hanged. It is believed that an imminent royal marriage between the Prince of Wales and the sister of Philip of Spain prompted the Portuguese to release their prisoners and Pory finally returned home. John Pory spent the years until 1625

travelling between Virginia and England investigating and reporting on the affairs of the Virginia Company for the government. This employment ceased on the death of King James. It is thought that Pory spent the remainder of his active life in London, continuing to earn a living from his newsletters. He remained unmarried, possibly having been rejected by a young lady shortly before he began his first travels. His last known letter was written in 1633. He then disappears into obscurity and it is not even definitely known when or where he died. He could have died in London. Many registers were lost in the Fire of London, making it difficult to trace deaths. It is equally probable, though by no means certain, that he died in 1636 and is the John Pory buried in the ancestral home of Sutton St Edmunds. Many other family members had remained there and John is certainly not an unusual name. It seems a shame that a man who achieved and recorded so much died unrecorded. Few people in Britain have ever heard of him. Although this is not so true of the USA, much of his life was only uncovered when William Powell was a university student. Pory was pointed out by his tutor in a painting depicting the first Legislative Assembly, with the comment that he was the person in the painting that least was known about. William's challenge was to research him for his thesis. Little did he know this was to be a lifetime's passion. Many years after he wrote his book on Pory, William Powell was researching the family history of his wife, who is, by coincidence called Virginia. The icing on the cake was his discovery that she was related to the Pory family! Some things are just too strange to explain. Acknowledgements: I am indebted to Professor William S. Powell for his kind permission to use his work as a source: "John Pory 1572 - 1636, The Life and Letters of a Man of Many Parts", 1977, published by The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill Picture of Frontispiece is From Wikipedia Media Commons Library

HOW TO CONTACT LOOKING BACK

You can contact Julian by ringing 01953 881 885. You can write to him at 32 High Street, Watton IP25 6AE Or email on julian@midnorfolktimes.com I welcome contributions and memories to the above address. All views expressed in Looking Back are published in good faith and believed to be correct. BUT you should not rely on the accuracy of any information for any reason without independently verifying it for yourself. While every care and effort is made to ensure accuracy the publisher cannot accept responsibility for errors or omissions. This issue of Looking Back was published by : Julian Horn, 32 High Street, Watton IP25 6AE and printed Through www.quotemeprint.com

0845 1300 667

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 5

The LDV/Home Guard

Snow Pictures

Clarence House. The house had a monkey-puzzle tree in the front garden facing High Street. The resident of Clarence House was our Officer Commanding, Captain Oldroyd. Later on, Mr Walter Whalebelly moved into Clarence House. People off duty often played cards. Of course the ARP, Special Constables and others were also out and about. Although I was only 19 at the time I was made up to the rank of fullcorporal. I was, as I worked in the building trade, considered to be in a reserved occupation and was at first not called up. After a while I told the Labour Department I had changed my occupation to Lorry Driver and I was thus able to volunteer and accept the Kings shilling, and join the army. I later fought with the British Eighth Army in the Desert and in Italy. I spent over four years on Active Service overseas in and out of action. As builders, Waters and Sons built a number of pill boxes at Watton. There were also Dragons Teeth. These were rolled-steel joists, bent at right angles, which were inserted into apertures specially cut into the road. The purpose of these Dragons Teeth was to stop anticipated advancing German tanks. Nearby there was a supply of Molotov Cocktails an elementary incendiary grenade which we were suppose to throw at the tanks. All road sign post and milestones were taken away so these would not let the Germans know their whereabouts when they landed in England. Sadly I think, the milestones, many of which were quite Pictured are brother and sister, Olga and Deric Waters on a recent trip to Watton ancient, have never been kept our rifles at home. certainly in the early years of the war replaced I believe. The weapons we were issued with had when it was likely that the Germans Without doubt there were similarities been superseded by more modern would invade Britain. The guardroom between the Home Guard that I weapons. For example we, in the LDV, was on one occasion on the first floor remember and the very successful had Lewis machine guns which had of a room in what used to be The series Dads Army which has run for been used in WW1, whereas the George Coaching Inn in High Street many years. Many of us were keen to regular army in WW2 had the more (The George stood where Lloyds Bank do our bit, including the Old and the modern Bren Gun. stands today) That same room was also Bold and an assortment of other partIt was not long before the name LDV where both Olga and I first went to time soldiers. There was a wonderful was dropped and we became the school in the 1920s over 80 years spirit in those days when Great Britain Home Guard. ago! Our school friends included Dick really had her back to the wall. To a Most of our NCOs were men who Durrant, Kathleen Holmes, Maynard large extent the invasion of Britain was had fought in WW1. I remember H Brett, Vera and Sybil Golding, and called off by Hitler because the Royal Wright, who worked in Julnes shop Margaret and Norah Gompertz, all Air Force won the Battle of Britain, in High Street, was looked up to familiar Watton family names in those with dog-fights over the south-east because he had been awarded a days. of England, and took command of the military medal for bravery on the On another occasion the guardroom skies. As Churchill phrased it: Never field of battle. There was tall Zeb was half way down Back Street. This was so much owed by so many to so Page, from Carbrooke, who had been was an out-building belonging to few. By Deric Waters In a recent issue of The Wayland News, I published a photo of the Watton Carbrooke and Ovington Home Guard. In that picture was Deric Waters, son of Dan Waters of the well know building company, Waters and Sons, in Thetford Road. I sent Deric the picture and asked him for his memories . . . After Hitler overran the Low Countries and France, in May 1940, and Churchill took over from Chamberlain as Prime Minister, there was an announcement on the radio. The Local Defence Volunteers was to be formed. I went to the police station (then on Police Station Corner) and gave my name. No address was necessary. Most Watton people knew each other in those days. It was not long before we were asked to assemble. We were issued with armbands which displayed the letters, LDV and for the first few parades I took my fathers 12 bore with me. It was not long before we were issued with uniforms and rifles. We

a regular Coldstream Guardsman. I learned a lot about the army and medals from people like Arthur Flint and Walter Newby both WW1 veterans. We had parades, drill, weapons training and military exercises on most Sundays and some evenings. Occasionally there was a church parade. And, when the training or whatever was over, we repaired to the local pub and fought our mock battles all over again. Sometimes the pubs ran out of beer as there were many regular troops in the district. Many things were in short supply. It was patriotic to patch your clothing. People were exhorted to Dig for Victory grow your own vegetables. I can remember spending quite a lot of time one Sunday up a tree near the churchyard where I was supposed to be a sniper. On one weekend Arthur Flint and I attended a map-reading course at Britannia Barracks, on Mousehold Heath, in Norwich. The Home Guard was also on patrol in Watton every night, in the black-out,

Again from Ruth, these are pictures around Watton in the snow in what must be 1953 or 1954. Starting with the premises above that were Studio Khyber but are now the PACT Shop near Wayland House.

Above: Jack Cross, The Post Office and Edwards Newsagents and Below Daveys, Chemists and Adcocks

The Shipdham Cash Supply Stores - No longer there but was on the corner opposite the church

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 6

A Family in Watton - 1907/10 But where and who?

I really need your help here! In the material from Ruth are four boxes of glass plate negatives each containing about 10 plates. Each box is marked Watton and then a date. They come from 1907 to 1910 but have suffered water damage to at some point in their lives, although a great pity, given that they are 100 years old, it is remarkable they have survived at all let alone in the stunning quality of tone they have. They appear to be typical family snapshots of life at the time and are mostly portraits of what I take to be the family with occasional ones of the house and animals and two rare pictures actually inside a room in the house. It would be good if we could identify the house and ever better identify who the family are. I have not yet been able to scan all the plates but I have reproduced here what I think may be the best of them. There is still much to do in analysing the changes over the years covered but here they are for your enjoyment and, I hope, identification.

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 7

All the pictures of the building on this page including the picture from inside the conservatory are from the 1910. The room shot however is from 1907. Inside the bookcase I can make out a Harrods catalogue which leads me to think these were well off family. This thought is reinforced by the picture left of the maid feeding the geese.

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 8

Loch Neaton 17th May 1948

Another set of negatives from Ruth. This time Loch Neaton on Monday 17th May 1948. Obviously a holiday and I think it must be Empire Day which was celebrated normally on 24th May, a now largely forgotten anniversary, perhaps only your grandparents will recall the chant Remember, Remember Empire Day, the 24th of May. Whatever the holiday it looks like a good turn out!

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 9

More Schooldays

These pictures come from Sue Dockray and are of the pupils improving the grounds at Watton Area School in the late 1930s. The captions are as shown in the album

1937: Beginning the draining pool.

1937: Improving the Girls Playground

1937: The Main Path Completed

Summer term 1938 English class on the lawn

Early 1937. Removing stumps of trees by pulley tackle

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 10

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 11

A Wednesday in the life of Watton in the 1970s

Amongst the material that has recently come into my care from Mrs Ruth Dwornik, whose business went under the name of Studio Khyber, is a set of colour slides. The slides are undated, however it looks as if they come from around 1973 or 1974 - but if you know different, or can identify any of the people in the pictures, I shall be very pleased to hear from you! It appears that Ruth went around the town one Wednesday capturing scenes from the activity and we start with much loved Archie Manning (right) delivering the daily milk to Durrants in the High Street. Next along the top is inside Buthchers hardware store which was demolished and replaced by Rudlings Hardware Store. Then inside Adcocks - interesting to see how prices have changed! The middle row below shows Garnet Mitchell at work in the pharmacy at Horsburghs Chemist (now Adcocks new shop). Next is a view inside Leeks near the New Inn, Then the Watton Driving School in Middle Street now the cafe. But I don't remember the gentlemans name do you? Then Dick Marsham and seated an unidentified person at Bretts Stonemasons. The bottom row starts with an unknown lady in Harmans Clothing factory on Norwich Road beside the Regal Cinema, then inside Durrants - but who is serving? Shes so familiar! Then in the bar at The Crown - again three familiar faces but the names escape me.

Lastly, left is Mr Charlie Wells, vegetable and fruiteer. The business of CC Wells still trades on Watton market place today. And above is a cafe which must have been near Ogdens wool shop but again my memory fails me! With the kind permission of Mrs Dwornik, I can supply reprints of these pictures.

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 12

The Doomed Squadron

Until 7 August 1981, I had never concerned myself with history except for normal. On that special day official matters took a colleague, Leif Bradsted, and myself to the western part of Aalborg at the bank of the Limfjorden where a new marina was under construction. Here we were to examine the area where some remains of an aircraft had been excavated from the mud of the sea bed. Obviously, the remains: two radial engines, propellers, landing gear etc. belonged to an aircraft which might have crashed into the Limfjorden during the war. Having discovered the wreckage-parts the workers of the contractor company, Mortensen & Nymark, didnt dare to carry on the excavation work of the basins but claimed an examination for any sleeping bombs at the finding place. The next day our work continued at the place without any success. We were not able to identify the parts of the wartime wreckage - I didnt know anything about the British Blenheim bomber type at that time. Besides, I had never heard or read about the disastrous air combat over Aalborg on 13 August 1940. The fact that we could have called for most qualified assistance and got the right answers to all our questions about the wreckage had we only been aware that two of the survivors of the air-combat: Bill Magrath and John Oates, this very same day were visiting the Air Base of Aalborg situated right north of the finding place and just across the Limfjorden. Here they spent the day, invited as special and honoured guests. Only later did I hear about that and missed the opportunity to meet them. A few days later our task was solved in a satisfactory way and the constructing of the marina went on. No bombs were detected. Having investigated the police archive in Aalborg an old report came to light and told that a Luftwaffe armourer, Feldwebel Klein, some time after the air combat, had demolished ammunition from the wreckage of an English bomber, shot down and crashed into the Limfjorden near the finding place of the wreckage. During this work he and his German helpers found the body of a British airman in the wreckage. No name of the airman was recorded. In other words, Feldwebel Klein had in some way done our work 41 years ago. However, still many questions were left unanswered and I therefore made up my mind to obtain more detailed knowledge to the wreckage parts of the unidentified aircraft. The old police records told me that eleven British bombers were shot down by German fighters and anti- airguns in the noon of 13 August 1940. One of them crashed into the Limfjorden near the southern bank at the fluepapiret(flys paper) - a position near the place where the wreckage parts appeared now 41 years later. I therefore concluded that the scrubby parts were belongings to the above mentioned bomber. But which of the eleven bombers and where exactly did the other ten bombers crash, with what crew, and why? No files or old records were of any help. No aircraft numbers were recorded. To solve that and many other questions in myself given task it soon became clear to me that I had to start at the very beginning. Only little did I know at that time that the following years should bring me on a long and interesting journey into history and get so many wonderful English and Danish friends. I started to do a more proper and systematically study of the police records of the wartime. I also studied the old newspaper articles from the Aalborg area. Thanks to journalist Birthe Lauritsen, Aalborg Stiftstidende, I learned about a very interesting article concerning the Air Combat over Aalborg, printed and presented in the Aalborg Stiftstidende for the readers already the day after the combat. Some written history is based on myths and rumours, so, every single item and information had to be double checked, this included what Danish eyewitnesses and the survivors of the raid told me. Otherwise, I would certainly break my neck like many other amateur historians had done during the years. In 1982 I was granted a journey to London to attend a conference and exhibition related to my job. This journey gave me opportunity to search for more information concerning my story work and I decided that, in what was left of spare-time, I got to visit The RAF-museum and The Public Record Office in Kew. Besides that, I had very strong feelings that I should try to get into contact with one of the survivors of the raid. One of the eyewitnesses here in Denmark, a very nice woman, Mrs Elisabeth Jrgensen, who lived in the Kaas area during the war, had informed me of names of two of the survivors who came to her home a few hours after the combat. Later in the afternoon they were captured by the Germans. Their names were: R.A.G. Ellen and John Bristow. Ellen lived in Kent, Bristow in London, as far as she knew. I therefore decided to try making a contact with John Bristow if he still lived in London. To me, as a Dane, the name Bristow sounded very rare and it would surely be a piece of cake for the foreign information service of the Danish telephone company to find his telephone number - I thought in my great naivet. I called the information service and asked for the number of John Bristow in London. A minute later the kind woman in the other end of the wire asked me: How many of them do you want? Theres about 50 with the name Bristow in the London area, she informed me. I almost gave up but asked the woman just to give me four numbers, selected by her free choice. And, believe it or not, the very first number I dialled was answered by Daphne Bristow who, on my request, told me that her husband John was an airman during the war and was shot down with his bomber in Denmark in August 1940. Besides that, she said to me that John surely would like to meet me during my visit in London and tell me about what he experienced on the fatal mission. My first meeting with Daphne and John, the great hospitality they showed me and later my family, the mutual friendship, Johns most interesting story as a wireless operator/air gunner and his almost 5 years as a POW in Germany during the war, made me work even harder. And I cant find word to tell

The Doomed Squadron

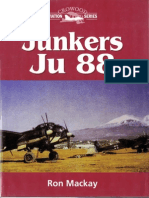

The following story has been extracted from a book compiled by Ole Ronnest who, prior to his retirement in 2006, served with the Forensic Department of the Police in North Jutland as a so-called scene of crime officer. Normally dealing with work of a forensic nature, Oles job included investigating cases where munitions were found by people, including wartime ammunition and bombs. In such cases Ole always cooperated with experts from the army demolition service. In his career, Ole has investigated the wreckage of many RAF aircraft that have crashed in Denmark and has told the story of many brave airmen. In recognition of his unique and remarkable work Ole was awarded the rare honour of an Honorary MBE in 2000. In this article Ole tells, in his own way, the story of his investigations in the raid by 82 Squadron, based at RAF Watton, on Aalborg in Denmark on the 13th August 1940. A raid that cost the lives of 20 men on the day and changed the future of the survivors. Ole is pictured left on 13th August, 2000 when the worlds only flying Blenheim made a most moving return to RAF Watton.

how very much I admire John, a very great character and gentleman who sadly died on July 15th, 1990. John introduced me to John Dance in 1983, another of the survivors of the raid who was Observer with Ellen. As time passed by I had the great fortune to get in touch with Paul Lincoln and Julian Horn, both of Watton in Norfolk, who, in spite of their young age, had carried out years of painstaking work to build up a very fine wartime museum at the old Watton Station and to secure the wartime story of the station and the city of Watton as well. These two men gave me new and most important information and historical pictures for the story. They, too, introduced me to many new friends all around in the Commonwealth, who experienced the wartime, either by maintaining the aircraft or flying missions out from Watton and who so willingly told me their story. Attending a reunion in Watton in 1995 the fortune once again smiled to me when I met another indirect survivor of the mission, Don McFarlane. Don luckily saved his life in a special way on 13 August 1940, when he and his crew was ordered out of their Blenheim (R 3821) only few minutes before take off from Bodney (the satellite airfield of Watton). A new crew: P/O Earl Robert Hale, Sgt. Ralston George Oliver and Sgt. Alfred Edward Boland, was to take over the aircraft. Soon after they flew to their death in Aalborg. Don has given me outstanding assistance concerning his story and supported me with new and interesting pictures which suddenly became of greatest interest as the wreckage of his Blenheim, most unexpected, appeared and called for my attention on 13 September 1995 - 55 years and one month after the combat. In May 2000 The City of Aalborg commemorated the 55th anniversary of the end of the German occupation of Denmark in a spectacular way. In the afternoon of 4th May a close formation of three F-16 fighters of Air Station Aalborg and the only flying Blenheim in the world, The Spirit of Britain First, flew in low altitude along the Limfjorden from east heading west to the island Egholm. In the morning of 5th May the Blenheim, in its fine colour sceme: UX-N No. R 3821, carried out a ceremonial Fly Past over the Commonwealth War Graves in Vadum to honour the memory of the fallen airmen of WWII. The event took place only thanks to Colonel Karsten Schultz and his staff of the Air Station Aalborg, Director Winston Rose and his staff of The North Flying A/S, Director William Bluhme and his staff of the Aalborg Airport, the Chief of Security of the Aalborg Airport Henrik Jensen, the Mayor of Aalborg Henning G. Jensen, Director of Administrative Service Anni G. Walther and her staff of the Aalborg Town Council, Financial Manager and President of the Royal Danish Aero Club Aksel Nielsen, the Board members of the Chr.IVs Laug, members of the Brothers of Defence Association in Aalborg, Nrresundby and Environs, British Consul Jrgen Bladt of Aalborg, Senior Commercial Officer R.G. Cobley of the British Embassy, members of the Home Guard of the Danish Air- and Army Forces, Journalist Lars Borberg, Nordjyske Stiftstidende, many sponsors, mentioned below, and most important: The Blenheim Team of Duxford, who, during many years and countless hours of voluntary and unpaid work, made a Blenheim fly again, reconstructed by derelict airframes of original aircraft. The visit to Aalborg of Blenheim UXN R 3821 could not have been possible without help and support from: Aalborg Erhvervsrd, Aalborg Havn, Aalborg Kommune, Aalborg Lufthavn, Flyvestation Aalborg, AndersenFarmer Kommunikation, Bo Jensen Vandbehandling A/S, BP (British Petroleum), Chr. IVs Laug, CMIndustries A/S, Falck, Flyvestation Aalborg, Friheds-kampens Veteraner, Frup AquaPark og Sommerland A/S, Lilleheden LNJ res Limtr, Director Ole Lippmann (SOE Chief in the Field in Denmark during the last months of the war), Metax, Muk Air, NCC Danmark A/S, North Flying A/S, QFaldskrmscenter, SAS, Hotel Scheelsminde, Shell A/S, Sol og Strand A/S, Spar Nord Bank A/S, TeleDanmark, TopDanmark, Tradex International ApS, UniDanmarkfonden, Unicon Beton, Wieben Design. I am indebted to Jrn Junker who willingly sent me copies from his private collection of relevant German records and many historical photographs for free use in this book. I am also indebted to Birger Hansen, Claus Kofoed, Henrik Skov Kristensen, Frank Weber, Carsten Petersen, Sren Flensted, Ole Kraul, Ib Ldsen, Birthe Lauritsen, Lars Borberg, Henning Bender, Erik Rasmussen, Henning Skree og Henning Kristensen for great support and interest in my work with the story. Aabybro, February 2007 Ole Rnnest

The Doomed Squadron

Owing to my knowledge of the English language, I would never succeed to write the story of the Doomed Squadron. I therefore became more than happy when the writer and historian, Ralph Barker, in 1984 sent me a letter in which he asked for my assistance to secure the story for posterity. And I am happy to tell the reader that Ralph Barker mastered to write the story to perfectness. And now, so many years later, I therefore have decided to quote his story as I think it will be almost impossible for you to get a copy of his book today. And, thinking about the many hours I have spent in writing all the details, produced maps, photos, countless telephone calls to him with details etc. for his free use; I know he will accept my wish to inform the reader about his great work and not least, to tell the tale of the disastrous Aalborg Attack in August 1940. Bear in mind, please, I did the research work from the very beginning to the very end without thinking of any gain. In his book: " That Eternal Summer" , chapter 4, Ralph Barker wrote the story of The Doomed Squadron as follows: The New Squadron Commander was an unknown quantity. The squadron much preferred the old one. They had learned to love the irrepressible Irishman Paddy Bandon, Wing Commander the Earl of Bandon, known throughout the Air Force as the Abandoned Earl. He was a hard act to follow: extrovert, gregarious and party-loving, his deep throated laugh penetrated the farthest workshop and store. The squadron, which had been through difficult times under his leadership, resented his going. His successor, Edward Lart - Edward Collis de Virac Lart, descended from a line of French noblemen who traced their ancestry back to the eleventh century - was an introvert and a loner, reticent and withdrawn, desiccated by long service in India, with a dry, sardonic sense of humour to match. Max Hastings, writing about him in his book Bomber Command, called him 'a chilly, ruthless officer who feared nothing and had no sympathy for others who obviously did'. Yet he had two things in common with Paddy Bandon. He was dedicated to moulding and efficient squadron. And he was determined to lead from the front. After tragic losses during the Battle of France, Bandon's mission had been to ease No. 82 Squadron, based at Watton in Norfolk, back to selfconfidence in time for the next German assault. Lart, as this assault developed into what was to become the Battle of Britain, was not so considerate. To the squadron Ted Lart was an enigma, and humours about him proliferated. Among the more colourful were that he had been despatched in disgrace to India and that while serving there he had lost his wife and children in the Quetta earthquake of 1935 - an experience, it was thought, that accounted for an aggressive bravery that some saw as recklessness and bravado. He didn't care, it was said, whether he lived or died. However, the facts were that he was not in India at the time of the earthquake and that, although no misogynist, he was and always had been a bachelor. Other rumours - that 'he had come to the squadron straight from overseas, sent home, because of some social indiscretion, as abruptly as he'd been sent out, and that he had no war experience outside the bombing of recalcitrant tribesmen - possibly held more substance. He does seem to have been despatched overseas in a hurry, and he had been back in Britain no more than a month. But in that short time he had learnt to fly Blenheim with one squadron and done four raids over enemy territory in a week with another. Of scarcely average height, slim and physically fit, Lart in his fortieth year retained a luxuriant head of chestnut hair which was the envy of many younger men on the squadron. He retained, too, a youthful capacity for risk-taking. Whether peace-keeping from the air on the North-West Frontier, where he had twice been mentioned in despatches, or hunting big game on lone forays into the hills, he was accustomed to physical danger. Indeed it might be said that he looked for it and thrived it. Thus his allegedly hurried return from India seems more likely to have been stimulated by his own anxiety to get into the fight. If there was any man in the Air Force likely to take on an impossible mission and make a

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 13

UX-W a Blenheim of 82 Squadron, Watton Airfield 1940 before he's half-way across the Channel.' The crews were all peacetime regulars or reservists professional airmen to a man, but under severe nervous strain. Their courage was not often in question, but they were mostly content to stick to the book, happy, when vindication seemed certain to live to fight another assembling for the projected German invasion, and so did one of his senior pilots, the lean, balding Flight Lieutenant Ronald 'Nellie' Ellen. Ellen found Lart ascetic and uncommunicative, but he fully supported his efforts to revitalize the squadron. On 28th July Lart's was the only one of seven crews to bomb the Dutch airfield at Leeuwarden. Three days later, on 31st July, Air Commodore James Robb, Air Officer Commanding 2 Group, recommended Lart for the award of a DSO. The citation concluded: 'By his courage, devotion to duty and skill as a pilot he has set an inspiring example which has more than maintained the excellent esprit de corps of all ranks under his command.' When thirteen out of fourteen aircraft returned for lack of cloud cover early in August, Lart attacked Boulogne airfield from low level and suffered superficial damage from his own bombs. He used this as a stick to beat his crews with. 'That', he said, pointing to the damage, 'is the level I expect you to bomb.' In one crew, a dilatory gunner was left behind because Lart wouldn't countenance further delay. Some said he was mad. Others noted a dramatic improvement in time-keeping. Meanwhile the inability of the daylight Blenheim to play a significant role in the Battle was worrying commanders and Air Ministry alike. Spitfire and Hurricane pilots were locked in a fight to the death with the Luftwaffe in those first days of August, and Air Marshal Charles Portal, C-in-C, Bomber Command, ordered daylight precision attacks on enemy airfields, aimed at harassing concentrations of German air strength. But he did not change his opinion that such attacks without cloud cover would prove disastrous, and the insistence on such cover remained. Under this embargo, pilots were again and again forced to turn back. Yet the Blenheim could not be left to stand idly by while Fighter Command was overwhelmed, and 82 Squadron were ordered to practice formation attacks at high level. Judging from experience in France, these too seemed doomed to failure. At 20.000 feet the Blenheim was sluggish and sloppy, inviting attack, and making close formation flying an additional strain for the crews. When the revised tactics were tried out on 7th August there was an ironic twist. From 20,000 feet the target was cloud-covered and the raid was aborted. On the afternoon of 12th August, Lart received orders from 2 Group for a high-level formation attack on the bomber airfield at Aalborg West in Jutland by twelve Blenheim. It was a grass field, but since occupying Denmark the Germans had refurbished it, though the work was yet completed. Targets to aim at would be parked aircraft, dispersals and airfield buildings. British Intelligence had wind that some fifty Junkers 88 bombers were massing there for 'Eagle Day', together with Junkers 52 troop transporters for the invasion. The pressure on Portal was mounting. Aalborg was the limit of Blenheim operational range. The bombing height was to be 20.000 feet 'if possible', in the hope of escaping the defences, but Lart doubted whether this was feasible or even desirable. It was doubtful whether, with the aids then available, they could bomb accurately from that height, and they would probably be equally vulnerable. In any case such an attack would depend on clear skies. Meanwhile a significant phrase had begun to appear in group orders: 'irrespective of cloud cover'. And '20.000 feet if possible' gave formation leaders considerable latitude. Even at 20,000 feet, however, the Aalborg plan, without fighter cover and in daylight, looked suicidal. But the orders and the implications were clear; it would be useless to argue. Lart would simply be told that either he led the raid or made way for someone who would. Even if he had a mind to protest, he would not save a single one of his crews. All he would achieve would be personal ignominy and the saving of his own skin. There is no indication that he resisted. Late that afternoon he drew Ellen aside. 'Take the chaps into Norwich this evening. You can use squadron transport. But don't be late back. It'll be an early start tomorrow.' The condemned men were to be given a hearty supper. At 5.30 next morning, 13th August, the crews were awakened. They were due to take off at 8.30. When they learned the target, most were resigned to their fate. They just hoped for a miracle, or to survive as prisoners. Many found a quiet moment to write letters to loved ones, to be posted if they didn't come back. Briefing was tense and succinct. The load was to be four 250-lb. highexplosive bombs and eight 25-lb. splinter bombs to disable parked

Pictured above are the two contrasting commanders of 82 Squadron on the left is the Earl of Bandon on a return visit to RAF Watton in the early 60s and on the right Edward Collis de Virac Lart. success of it, Lart was that man. 82 Squadron formed a part of No. 2 Group, the light bomber group of Bomber Command. From 1st July 1940, when Lart took over the squadron, the crews operated individually, bombing airfields in France, Germany and Holland, though in daylight they were required to stick rigidly to their brief to turn back without adequate cloud cover. 'Tasks', ordered Bomber Command, were 'to be carried out only to the extent which is rendered possible by the conditions prevailing at the time'. This was in consideration of the extreme vulnerability of the twinengine Blenheim to German fighters, which had been pathetically proved in the Battle of France. The result, for many of the pilots, and especially for Lart, was frustration. 'I'm sick of all this turning back', said Sergeant pilot John Oates (right), thirty-two years of age and a Yorkshire man. A fellow pilot reacted differently. 'Look, Johnnie - the blokes who didn't turn back are nearly all dead'. Lart took a cynical view. Once, when a pilot who had forfeited his confidence was taking off on a bombing mission Lart was heard to mutter: 'I suppose he'll find some excuse to creep back - probably day. Lart, privy to a deeper insight into the course of the Battle, knew that 'another day' might be too late. On raid after raid it was Lart who pressed home the attack. On 7th July he penetrated 300 miles into enemy territory alone and in daylight to attack Eschwege airfield. Invariably he followed up his incursions with a vital reconnaissance, noting Luftwaffe dispositions. Of ten crews operation on 18th July, eight turned back, but Lart attacked canal barges

Johnnie Oates

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 14

(Lart was taking a more direct route than the one originally planned, to conserve fuel), the crews saw with alarm that the cloud was dispersing. Suddenly Magrath realized that he had a premonition after all. He wouldn't get back from this one. He had bought a one-way ticket. None of the pilots expected Lart to turn back, though one was about to do so. This was Sergeant Norman Baron, No. 6 in the second section. Baron's fuel gauges were playing up, recording an excessive consumption. At first he thought it might be the gauges, but he became convinced that the gauges were right. They were still some way short of the Danish coast when he broke radio silence to tell Lart of his problems, then tailed off. Lart's comments are not recorded. He continued on course. That Lart was interpreting his orders correctly was underlined when, after Baron's problems had been provisionally diagnosed back at base as a 'supposed fuel shortage', he was placed under open arrest awaiting court martial. Meanwhile a German observation post on the Danish coast at Sndervig, near Ringkbing, had reported the airborne invasion. From its estimated heading the target looked likely to be Aalborg. Soon afterwards the air raid alarm was sounded in Aalborg and the crews of the anti-aircraft gun emplacements there were alerted. British Intelligence had been accurate about the positioning of the Ju 88 bombers - they had recently been flown down from Stavanger. What was not known was that, to support them in their bombing of Britain, eight Messerschmitt 109E singleengined fighters of Fighter Geschwader 77 had been switched south from Norway to the fighter airfield at Aalborg East and another twenty-five - the remainder of the Geschwader - had been posted to Jever, near Wilhelmshaven in North Germany, in preparation for Eagle Day. The smaller Aalborg section, and the pilots, was immediately scrambled. As the eleven remaining Blenheim motored at 8.000 feet and at 180 miles an hour across the flat Jutland landscape in bright sunshine, a veritable hornets' nest was being stirred up to receive them. Lart, continuing on a north-easterly course, doubted his own and anyone else's ability to hit specific targets from 8.000 feet, and he began a shallow dive down to 3.000, intent on plastering the best targets before swinging left towards the North Sea and Scotland. The others in A Flight followed in close formation. Rusty Wardell, however, leading B Flight, elected to vary the direction of his attack, hoping to confuse the defences, and he started a detour to starboard, planning his attack from that angle. His flight, reduced to five, kept in close. When the alarm at Aalborg was followed by the staccato detonation of guns, the townsfolk began hurrying for shelter. But some stayed to see what would happen. 'I looked up and saw about ten English bombers,' said one eye witness. 'They seemed to be in two different formations, flying in finger formation at about 3.000 feet.' Long before Lart's flight reached the airfield, the guns on the shores of the fjord were probing for their range. The German tactics were to hold their fighters off until the target were positively identified, relying on the

The Doomed Squadron

R3800 Z-Zebra in its final dive. A propeller from this very aircraft was recovered in the 1980s and is now the Memorial at RAF Watton ground gunners, if it proved to be Aalborg, to put the bombers off their aim. The airfield was surrounded by guns. Puffs from a random succession of explosions curtained Lart's flight as they swept on in tight formation towards the airfield. Several of the Blenheims were hit by shell fragments on the run in, making pinpoint accuracy impossible, and one crew, on the port side of Lart, piloted by Yorkshire man Johnny Oates, forgot all past frustrations as direct hits in the wings and an engine somersaulted their plane. Diving steeply, the Blenheim seemed certain to crash, but miraculously Oates retained some measure of control. Flattening off but letting the dive continue to low level, he jettisoned his bombs on the airfield and hedge hopped north-west as best he could on one engine. The rest of Lart's flight suffered further hits and all dropped their bombs under pressure. They caused only minor damage and inflicted few casualties, the only fatal ones being three Danish airfield workers. As they veered to the north-west, the fighters moved in for the chase. The crews of Lart's flight had seen four German fighters taking off at they approached the airfield to bomb. Now others were joining them. Meanwhile those Danes who had stayed above ground to watch saw five more Blenheims approaching in impressive but vulnerable formation, presenting what looked like an unmissable target to the German guns. First of Wardell's flight to suffer serious damage was Blenheim C for Charlie, flown by a young Pilot Officer named Douglas Parfitt. Forced to release their bombs over the farmland area at the Restrup meadow, short of the target, killing some cattle, Parfitt and his crew, Sergeants Youngs and Neaverson, were already struggling to stay airborne when their plane received a direct hit that severed the tail. Eyewitnesses saw the plane pirouetting down in two pieces, with little hope for the crew. In fact the Navigator, Leslie Youngs, got clear of the plane but his parachute failed to open and he fell with his comrades to his death. The four remaining Blenheims presented an almost point blank target to the gunners as they raced in to bomb. All were hit before reaching the target, the two at the rear staggering and quickly losing touch with the others. One, Z for Zebra, flown by Flight Lieutenant T.E. Syms, turned abrubtly on its back before settling into an incandescent dive south of the target, off the island of Egholm. As it blazed towards the water an alert German soldier, camera at the ready, preserved its final plunge for posterity (above). Syms, a distinctive figure with flaxen hair and abnormally high cheekbones, having already ordered his crew to jump, got out himself, alighted in shallow water, and was helped ashore by German soldiers. His navigator, Sergeant Wright, also escaped, though while pirouetting down towards the fjord he found himself the target of a stream of bullets from one of the Messerschmitts - or so he imagined. Almost certainly it was a stray burst aimed at another Blenheim. Alighting near Syms, Wright was also assisted to the shore. There he got the traditional greeting from a group of German soldiers. 'For you the war is over.' There was no trace of animosity - but Syms's gunner, who was missing, was later found dead in the plane. Bill Magrath, lying on his tummy in the nose of Blair's aircraft, was manning the backward-firing gun and banging off at everything in sight, knowing he was the last one in, with nothing but Messerschmitt behind him. He didn't expect to hit anything, but he might scare them off. Soon after dropping their bombs they lost an engine, and then the Blenheim caught fire. As the blaze scorched his eyebrows Magrath decided it was time to get out; then he saw the waters of the fjord racing up towards him and realized he'd left it too late. Blair was aiming to ditch in shallow water north of Egholm. What he didn't know was that boulders below the surface were waiting to rip open the plane's under-belly. Next thing Magrath and his gunner, Bill Greenwood whose POW picture taken by the Germans is shown below, knew they were lying in the water with lifejackets inflated. Floating a few yards away was their pilot, Don Blair, his face so

The dotted line shows the planned route to Aalborg and the solid line shows what was the actual route flown. aircraft. Flak and fighter opposition must be expected, but the aim was to put aircraft and support buildings out of commission, and the attack was to be pressed home at all costs. The importance of destroying the Junkers 52 transports, which it was thought would be obvious targets, was stressed. All crews were to coordinate their actions with Lart's, opening their bomb-doors and releasing their bombs simultaneously to far as was possible. They were not to attempt to get back to their base in East Anglia, which would be out of range, but were to take the shortest route back to Britain and put down where they could in the north-east of England or in Scotland. When Ellen's navigator, Sergeant John Dance, climbed into his Blenheim, the D-ring of his parachute snagged on an obstruction, exposing the canopy. 'I'll have to manage without one,' said Dance. But Ellen, standing up to an impatient Lart, insisted that Dance go back to the parachute section for a replacement. Other minor delays had already proved sufficient to allow one crew, whose posting notice had just been opened in the orderly room (they had been flying operationally since September 1939), time to be recalled, their place in the formation being taken by the stand-by crew. Thus the experienced Flight Lieutenant D.M. Welling, a brother of E.M. Wellings, cricketer and cricket writer, gave way to Pilot Officer E.R. Hale. Canadian, Hale (pictured below) had been on

Bill Magrath at the end of the war case, he took care, as was his habit, to eat the whole of his chocolate ration before take-off. No one else was going to get that. He and his pilot and gunner were all aged twenty. The morning was fine, but after they crossed the Norfolk coast the sea was hidden by a layer of cloud. Lart led them up to 8,000 feet, then levelled off. They had formed up into two flights of six; each flight split into two vics (V-formations) of three; the whole stepped down from the front like a ladder. Lart was leading A Flight, while leading B Flight, which had taken off from the nearby satellite airfield at Bodney, was a ginger haired squadron leader named 'Rusty' Wardell. Ahead lay a flight of exactly four hundred and fifty miles, stretching the Blenheim to the limit of their endurance. Throttle manipulation to maintain station at high altitude would have reduced their margin still further, and it became plain that Lart intended to stay at 8,000 feet. Reflecting on this, Rusty Wardell twisted the ends of his incipient handlebar moustache even more fiercely than usual. Lart faced an impossible dilemma. If they stayed at their present height, and the cloud evaporated, they would get the worst of both worlds. But 20,000 feet he dismissed as impracticable. Better to fly at heights to which they were accustomed. Rather than be frustrated by cloud, as had happened six days earlier, and having regard to the phrasing of his orders, he elected to stay where he was. Two hours later, as they approached the Danish coast near Ringkbing

the squadron a fortnight. Irishman Bill Magrath, a navigator with sergeant pilot Don Blair, often had premonitions about others, but never about himself. Today his mind was blank. Was it his turn? Just in

The Doomed Squadron

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 15

plan was discussed. But with no Resistance movement and no escape routes yet established, they had to agree that rather than jeopardize the Danish family the Germans must be called in. There were still three pilots airborne - Lart himself, Pilot Officer Wigley (first operation three days earlier), and the canny Sergeant Oates. All three were nearing the coast; all three were hoping to make it. One of them must surely get home to tell the tale. But the fighters persisted. A Danish citizen in Pandrup, close to the coast, heard 'a furious roar and thunder' as three twin-engine planes flashed over, hotly pursued by fighters, which jostled for position as they sought the bombers' weak spots. 'I became an eyewitness to the most hazardous stunt flying. All the time I could hear the hoarse rattle of machine-guns.' Showing increased sophistication as the fight continued, the German pilots attacked from below and abeam as well as from astern, forcing the Blenheim to fly through a vortex of fire. First one and then another fell steeply, leaving a trail of smoke and exploding with awful finality on impact. The pilots were Wigley - and Lart. Wigley had done incredibly well to get so far, as had his crew, Sergeants Patchett and Morrison. It was a baptism of fire that deserved a less tragic ending; their chances had been virtually nil from the start. As for Lart, sooner or later the cold dedication and hawk-like aggression of this highly experienced pilot, not far short of middle age, could have only one ending. All six men in these aircraft perished. Of Lart's crew Pilot Officer M.H. Gillingham, navigator, and Sergeant A.S. Beeby, gunner (pictured below), together with Lart himself - only Gillingham could be identified.

Above, Danes work to release seriously injured Bill Magrath from the wreckage of his aircraft, another shot of which is shown left. The wreckage is approximately 100 yards out from shore and Don Blair was expecting a fairly gentle ditching. spared; for a fraction of time the enemy pilot must have lifted his thumb from the firing button. He muttered a grateful 'Thanks, pal', then called his pilot. There was no answer. Peering through the fuselage he caught a glimpse of Jones, slumped over the controls. He could see no sign of his navigator, the aircraft was beginning to burn, and he decided to go. As he dropped through the rear hatch one of his flying boots snagged on some unremembered protrusion, leaving him suspended in mid-air. He kicked out frantically as the ground rose towards him. This was no way to die. Mercifully his boots were loosefitting and the trapped one slipped off his foot. One last thrust and he was free. But would his parachute open in time? He pulled the ripcord and hoped. Meanwhile Ellen's Blenheim, similarly blasted by fighters, and with no elevator control, was falling out of the sky. His intercom was dead, and he motioned to his navigator, John Dance, down in the nose, and shouted at him to get out. Dance wouldn't have had a parachute but for Ellen, and he blessed his skipper in that moment. Ellen could only hope that his gunner, Sergeant Gordon 'Taffy' Davies, had gone already. There was no word from the turret. He reached for the hatch above his head and pulled but it resisted all his efforts. It was jammed. The only hope was the nose hatch. In an instant he was down there, and with no time to count up to three he pulled the ripcord as he dropped through. He was jerked to a stop almost immediately, just as his feet sank into a swamp. Shocked by an almost simultaneous thump behind him, he turned to recognize Jones's gunner, Curly Bristow, whose parachute, like Ellen's had opened just in time. Jones and his navigator, Pilot Officer Thomas Cranidge, had been killed by the fighters, as Bristow had feared. The two Blenheim, Ellen's and Jones's crashed in nearby fields within a few hundred yards of each other. A farm labourer led Ellen and Bristow on borrowed bicycles to a house in an adjacent village, where they were given a meal and an escape

disfigured they thought he was dead. Magrath himself, with a smashed hip and shoulder, a broken leg, and severe facial injuries, was drifting in and out of consciousness when, with a half-revived Blair, he and Greenwood were dragged ashore by a group of islanders who had witnessed the crash. The Danes would dearly have loved to take them into hiding but were forced by the spectacular nature of their arrival to hand them over to the Germans. Pilot Officer Hale, who had taken Wellings place in the formation, stuck close to Wardell and got through to the airfield. His bombaimer, Sergeant Oliver, preparing to unload, appeared to be delaying the drop, saving his bombs for the German Kommandantura building, occupied at the time by the construction company refurbishing the airfield. Meanwhile gunner Sergeant Boland tried to fend off the fighters. But the plane was overwhelmed before the bombs could be dropped. It crashed almost vertically, not far short of the Kommandantura building, and the bombs exploded on impact, scattering fragments over a wide area. There was no chance whatsoever that Hale and his crew could survive. The last airborne Blenheim of B Flight was the leader, S for Sugar, with Rusty Wardell in the cockpit. His plans to qualify as a doctor after the war looked likely to be stillborn. Hit by shellfire on the bombing run, he had barely got rid of his bombs before his aircraft caught fire, burning him severely on the face and hands. He gave the order to bale out and jumped simultaneously, but his crew-men, Sergeant Moore and Sergeant Girvan, both perished in the seconds that followed. One was trapped in the plane, perhaps already

dead; the other got out at low level but was forced to pull the ripcord prematurely and was dragged to his death as the lines fouled the tail unit. The plane crashed in a convulsion of flames and exploding ammunition. Wardell himself landed heavily but safely near Vadum. A young Danish girl who stayed to watch while her friends sought shelter saw all five aircraft of B Flight crash, most of them on fire. These were Parfitt, Syms, Blair, Hale, and Wardell. 'You had to pinch yourself to see whether you were awake or dreaming,' said another eyewitness. 'The scene made such an impression that people around me were crying.' The sight of a charred body so sickened one member of the German occupying force that he wrote: ' I, as a man who is not a warmonger, wonder.Here lies a human being.' He noticed there was a ring on a finger, and began speculating on the reaction of relatives, pitying them in advance. But he added: ' I couldn't cry over him. I had to think of my many German comrades.' The six leading Blenheims, although under pressure from fighters, had got well clear of the airfield while B Flight were being demolished and had all swung away seawards, intent on making good their escape. But in A Flight, too, it was the second vic of three which bore the brunt of the initial fighter attack, the first victim being Pilot Officer 'Binjy' Newland, so nicknamed not for his beerdrinking capacity, though that was up to standard, but because his initials were B.T.N. Hit by flak over the target, he was striving to stay with the others when the fighters intervened. The square-jawed, open faced Newland could not evade the swarm that pounced on him, and he felt a searing pain as a bullet

penetrated his left shoulder. He was aware, too, from explosions around him, that his crew, Sergeants Cyril Ankers and Kenneth Turner, had been hit and were either wounded or dead. Despite his crippled shoulder, which greatly reduced his mobility, he managed to open the hatch above his head with his good arm. He had begun a despairing call to his crew when he was violently sucked out. Nellie Ellen and a squadron leader named Norman Jones, who was leading this second vic, managed to stick together and were now half-way to the coast. But the Messerschmitt were hot on their trail. Jones's gunner, Sergeant John 'Curly' Bristow (below), so called because of his crinkly fair hair, found air fighting not at all what he'd thought. Things were happening with bewildering speed. Although he believed he was accurate with his return fire the fighters seemed immune to it. In that second a dotted line of bullets raked the fuselage, yet the area around the turret escaped. To Bristow it seemed he had been deliberately

Gus Beebys wristwatch removed from his body by a Danish Doctor attending the crash That left only the Yorkshire man Oates. He knew he couldn't make base and he headed for Lossiemouth. As the fighters chased after him he felt no fear, only exhilaration, a reaction that must have been the last sensation of many. 'The bomber flew low over a village,' said another horrified Dane, and the combat continued at roof-top level between chimneys. Houses vibrated and villagers trembled as bullets whistled

Looking Back Issue 4 Page 16

The Doomed Squadron

Johnnie Oates in a Danish hospital was also a wireless-operator), who spent a tense and nerve-racking fiftysix months as a prisoner, building radios in secret so that his fellow prisoners could listen to the BBC news. In two different camps the hiding place was inside a piano accordion. One who has not attended but who kept in touch for many years is 'Binjy' Newland, from his medical practice in Australia. Newland was told by the surgeons in the hospital at Aalborg that the bullet in his shoulder was so close to the radial nervous system they dare not attempt to remove it, and there it remained until his death in February 1987. Norman Baron's explanation for turning back was accepted at his court martial. He was killed in action in May 1941 - but not before a DFM and a glowing citation had finally cleared his name. Wellings too was killed later. What of Edward Collis de Virac Lart? What should the summing up be? That Ted Lart was a complex character, and a leader who scorned to seek popularity, is inescapable, earning him the opprobrium which on further examination seems undeserved. although it was partly aborted - he set out to fulfil a task which he must have known was beyond the capability of the force he commanded, but which might still achieve something of value. Robb at 2 Group and Portal at Bomber Command clearly recognized his bold and dynamic leadership in those hectic weeks of mid-summer when, as already related, they recommended him for a DSO. The award was duly approved by the King on 17th June 1941, backdated to 31st July 1940. The loss of an entire squadron on a single raid has an epic quality, yet, as was historian John Keagan has written, no national epic is ever safe from irreverence. 'The urge to find the worm in the apple', he says, 'is irrepressible.' There were worms enough wriggling through into the Aalborg raid, principally from Britain's pre-war unpreparedness, but, amongst the air crews of 82 Squadron, including the solitary and much-maligned Lart, on closer inspection none can be found. It was Sergeant Donald Blair, Magrath's pilot, who penned the most moving tribute when writing to Lart's family soon afterwards from POW camp, a voluntary act lacking any of the advantages and disadvantages of hindsight. 'It was a pleasure and a privilege,' wrote Blair, 'to fly behind such a gallant gentleman.' The extraordinary amount of detail on the fate of individual aircraft and crews, even more comprehensive than has been utilized here, comes from a Danish detective-inspector, Mr Ole Rnnest, whose task it was, together with a colleague and an expert from the Danish Army Demolition Service, to investigate the site of one of the crashed Blenheim for unexploded bombs after fragments of the wreckage - it was Syms's aircraft, Z for Zebra had emerged out of the mud in 1981. Up to that point he knew absolutely nothing of the incident. Now he needed to know how the wreckage got where it was and whether further digging might disclose unexploded bombs. Told that after forty -one years he would never track down the full story or discover details, he responded to the challenge by diligent research into Danish, British and German records. The result was one of the most complete reconstructions of any wartime incident. Since then Mr. Rnnest has met most of the survivors of the raid and today numbers them among his personal friends; in 1984 he was made an honorary member of 82 Squadron. 'The incident,' he says, 'has changed my life.'

Johnnie Oates lying paralysed in the front of his crashed Blenheim around them, but they couldn't resist staying to watch.' Oates tasted the ultimate irony when, after shaking off the fighters and getting well out to sea, he was rejoicing with his crew when he glanced at his gauges and knew that a ditching was certain. With an aircraft more porous than a colander it would be suicide to come down in the sea. As he turned back towards land the fighters reappeared. The crash-landing he made under fire, on a bumpy meadow, knocked him out. Trapped in the cockpit, he was released by two Danes who had witnessed the scrap. When he recovered consciousness he found himself lying in a heap yards from the wreck with severe fractures to his back and his skull, injuries from which he would never fully recover. His navigator, Tim Biden, was also seriously hurt. Sergeant Tom Graham (pictured below), the gunner, escaped almost uninjured, and after an abortive search for a hide-out he returned to the Blenheim to burn all secret papers before the Germans arrived. Soon afterwards Oates and Biden were taken to the hospital at Fjerritslev. Aalborg West to raid north-east England, proving that airfield facilities were not crucially damaged by the sacrifice of the Blenheims. Yet the Luftwaffe, too, failed to provide escort for their bombers and suffered accordingly. Seven of the raiders were shot down by Hurricanes or Spitfires and three more crashed or force-landed on their return, virtually ending the threat from Air Fleet No. 5. Three days after the action, on 16th August, the twenty men of 82 Squadron who lost their lives in the action were buried side by side in the churchyard at Vadum (pictured below), north of the airfield they had sought in vain to disable. A German military padre spoke sympathetically of them and praised their courage, and a firing party and guard of honour, recruited from the crews of the anti-aircraft batteries which had caused such havoc among them, paid their respects. The ceremony was opposing pilots recognized each other: they had been at university together. Johnny Oates was told: 'The war will soon be over and you'll be going home.' Oates knew better. 'We haven't started yet.' Though the raid may have achieved nothing tangible, the impression it made on the Danes was profound. Such was its emotional impact that the seed was sown for the Resistance campaign which gave so much help to the Allies in subsequent years. Even today the Danes have not forgotten, and every year a memorial ceremony is held beside the long row of graves at Vadum, a ceremony which in recent years some of the few remaining survivors have attended. Among these has been Bill Magrath, who was one of a handful of prisoners to escape from Germany and get back to Britain, for which he was awarded a Military Medal. Others have been Johnny Oates,

For Headquarters Bomber Command the cost was clearly too great, whatever the missing crews might have achieved. The operations staff knew where they'd gone wrong, and next day they specifically ordered that no more formation raids were to be attempted without fighter escort. Two days later, on 15th August, when the full strength that the Luftwaffe had intended to deploy on the 13th was actually unleashed, thirty Junkers 88's of Bomber Geschwader 30 took off from

witnessed by members of the local population, who showered those in hospital with flowers, to the embarrassment of the Germans. Meanwhile, however, there was time for visits to the hospital and floral tributes from two of the pilots who had shot them down. Two of the

despite partial paralysis, and his navigator, Tim Biden; Ronald Ellen, awarded an MBE and the US Medal of Freedom for his POW activities and subsequently promoted to wing commander, and his ever-grateful navigator John Dance; also John Bristow, like the other gunners he

He fought the air war, in one of the RAF's darkest periods, with an aggressive dedication that did not always appeal to men who liked to feel they had some chance of survival. On 13th August 1940 which did indeed turn out to be Goering's Eagle Day as intended,

The Doomed Squadron