Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conflict, Security and Development.

Uploaded by

Duvaniro NivanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Conflict, Security and Development.

Uploaded by

Duvaniro NivanCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Nagoya University] On: 03 July 2012, At: 20:52 Publisher: Routledge Informa

Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Conflict, Security & Development

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccsd20

The role of private sector actors in post-conflict recovery

John Bray Version of record first published: 14 Apr 2009

To cite this article: John Bray (2009): The role of private sector actors in post-conflict recovery, Conflict, Security & Development, 9:1, 1-26 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14678800802704895

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Conict, Security & Development 9:1 April 2009

Analysis

The role of private sector actors in post-conict recovery

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

John Bray

Countries need active, equitable and protable private sectors if they are to graduate from conict and from postconict aid-dependency. However, in the immediate aftermath of war, both domestic and international investment tends to be slower than might be hoped. Moreover, there are complex inter-linkages between economic development and conict: in the worst case private sector activity may exacerbate the risks of conict rather than alleviating them. This paper calls for a nuanced view of the many different kinds of private sector actor, including their approaches to risk, the ways that they interact and their various contributions to economic recovery. Policy-makers need to understand how different kinds of companies assess risk and opportunity. At the same time, business leaders should take a broader view of risk. Rather than focusing solely on commercial risks and external threats such as terrorism, they also need to take greater account of their own impacts on host societies. Meanwhile, all parties require a hard sense of realism. Skilful economic initiatives can supportbut not replace the political process.

Introduction

There is no question that countries need active, equitable and protable private sectors if they are to graduate from conict and from post-conict aid-dependency. War leaders and their followers are less likely to return to ghting if they have an economic stake in peace.

John Bray is a political risk specialist with Control Risks, the international business risk consultancy. His professional interests include private sector policy issues in conict-affected areas; anti-corruption strategies for both the public and the private sectors; and business and human rights. He is currently based in Japan but mainly works on international assignments.

ISSN 1467-8802 print/ISSN 1478-1174 online/09/010001-26 q 2009 Conict, Security and Development Group DOI: 10.1080/14678800802704895

John Bray

External assistance has a vital role to play in the immediate aftermath of conict, but the long-term investment needed to withstand aid-dependency will most likely come from the private sector, or not at all. If all goes well, the social benets of equitable private enterprise will help sustain the legitimacy of the post-war political order. However, in practice there are two main problems. The rst is that both domestic andstill moreinternational investment tends to be slower than expected or hoped in the aftermath of war. If the economic rewards of peace are slow or invisible, there is an increased risk that conict will resume. The second concerns the complex inter-linkages between economic development and conict. In the worst case, private businesslike poorly designed international aid1may contribute to political tensions, thus exacerbating the risks of conict rather than alleviating them. With the second problem in mind Julien Barbara concluded an earlier article for Conict, Security & Development by calling for a more discerning approach to the positive and negative contributions made by different private sector actors to peacebuilding.2 He went so far as to suggest that in some circumstances private sector containment might be necessary for peace. This article responds to Barbaras call for discernment. It argues that it is essential to differentiate between different kinds of businesses, rather than speaking of the private sector as though it were a single entity. In particular, policy-makers require a realistic appreciation of how different kinds of companies assess risk and opportunity in the aftermath of conict. At the same time, business leaders themselves should take a broader view of risk. Rather than focusing solely on commercial risks and external threats such as terrorism, they also need to take greater account of their own impacts on host societies. This includes the possibility that companies could contributeoften unintentionallyto the underlying causes of political tension. Well-considered co-operation between public and private sector actors increases the chances of a virtuous circle of peacebuilding rather than a vicious circle of repeated conict.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

The legacies of war economies

Business of one kind or anotheroften including some form of trading with the enemycontinues even in war-time. In that respect, containment is scarcely an option. The most important questions are not whether private sectors develop (the plural

Private sector actors

is deliberate) but rather how and when they do so, and how to channel commercial energy in directions that are constructive rather than destructive. In war conditions even more than in peacetime, business people require political skills to survive, at least to the extent that they must be able to deal withor at a minimum coexist withpowerful military and political leaders. Post-war environments remain intensely political, and in that respect Michael Pugh is correct to highlight the weaknesses of technical economic strategies that fail to take account of the past and present political context.3 Both from a policy-making and from a commercial perspective, conicts leave painful legacies which impede the rapid development of healthy private sectors. The task of addressing these legacies requires a high degree of political astuteness, and there are no quick xes. The rst consideration is that in many casesperhaps mostthe structure of the pre-war economy was deeply awed, and this may have been one of the factors that contributed to conict in the rst place. At a 2006 conference at Londons Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA), Kanja Ibrahim Sesay of the National Commission for Social Action in Sierra Leone pointed to some of the factors that contributed to state failure and civil war in his country.4 These included excessive centralisation of decisionmaking; elite monopolisation of wealth; a political culture focused on the capture of resources for particular individuals rather than the generation of wealth for all; limited organisational capacity in government; and a climate of mutual suspicion between government and private sector. Even if restoration of the pre-war status quo were achievable, it would rarely be desirable. Second, while some kind of business almost always continues in wartime, protracted conict distorts and destroys normal commercial patterns. Some companies and individuals adopt coping strategies, adapting to new environments but following more or less mainstream business objectives.5 For example, Somali entrepreneurs have proved remarkably innovative in certain sectors, notably mobile phones, despite the absence of an effective national government since the early 1990s.6 In other cases, business people have developed new skillsand amassed huge protsin smuggling, black-marketeering and sanctions-busting. In the conicts of the 1980s and 1990s, such as those in Lebanon and Bosnia-Herzegovina, there were many examples of combatants trading with military opponents across their various frontlines. There is now an extended literature on the political economy of conict.7 One of the main themes of what has become a protracted debate is the extent to which the activities of both national and international rms contribute to conict rather than alleviating it, for example

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

John Bray

by providing a resource that contributes to military leaders war chests. Globalisation has enhanced the rewards of illicit private sector activity in conict zones. One classic example is the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); in 2003 a UN Panel of Experts issued a hardhitting report on foreign companies illegal involvement in the exploitation of natural resources during the countrys civil wars in the late 1990s and early 2000s.8 Once conict ends, one of the major tasks is to provide alternative sources of income for former combatants through demobilisation, disarmament and reintegration (DDR) programmes. In the rst instance these are often nanced through foreign aid.9 However, aid resources are limited and the lasting reintegration of former combatants is not sustainable without broad-based economic recovery, including the emergence of a dynamic private sector. In 2007 UNDP ofcial John Ohiorhenuan wrote of Liberia that employment opportunities are perhaps the single most important factor for sustaining the fragile peace.10 However, wartime political and commercial dynamics often persist in some form once the ghting has died down. Those who have gained power and inuence through patronage of quasi-legal or illegal commercial networks will wish to preserve their positions. For example, Pain and Lister point out that post-Taliban Afghanistan scarcely amounted to an open economy because aspiring entrepreneurs have to contend with existing commercial networks backed by powerful warlords.11 One outcome was that investment by both national and international companies was much slower than policymakers might have wished. The result has been fewer economic opportunities for ordinary people, and this has been a major factor increasing the risks of renewed conict. Mere promotional blandishments to investors will not be sufcient to address these shortcomings. If they are to nd answers, policy-makers need to take a realistic view of how different private sector actors assess and respond to risk.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Risk and opportunity in conict-affected environments

In the immediate aftermath of conict, the overall pattern of risks may not look so different from when ghting was still under way. The key problems include:

.

Poor security. This includes the risk of crime from ex-combatants, as well as the possibility of renewed ghting if the peace process breaks down. Lack of effective regulation. Government institutions typically lack experience and technical capacity. The regulation that exists on paper may be based on pre-war models

Private sector actors

that are no longer appropriate, for example because they belong to a socialist era that has now passed.

.

Widespread corruption. Post-conict environments are notorious for high levels of corruption, among other reasons because of the state of exceptionthe idea that exceptional circumstances place the main imperative on rapid spending, with accounting controls as a secondary consideration.12 Poor infrastructure. Basic transport and communications structure, as well as utilities such as electricity and water, have often been destroyed.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

The overall political framework is often determined by a ceasere agreement that is based on some kind of compromise between the main actors (as in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Lebanon). It will be hardif not impossiblefor local individuals or companies to present themselves as neutral parties. Their religion, ethnic identity or region of origin will almost always identify them with one side or the other. Even international companies are likely to be identied with one side or the other because of their government contacts or the backgrounds of their local partners, suppliers and sub-contractors. These conditions impede the commercial prospects of all kinds of businesses, whether these are individual entrepreneurs, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) or international companies. However, there are also opportunities arising rst from the reconstruction process itself and, more broadly, from the possibility that investors who are willing to take the risks of being among the rst-movers can establish themselves before their more nervous competitors.

Contrasting private sector strategies

The willingness of businesses to assume these risks depends on their appetite for taking chances, and this, in turn, is likely to depend on their geographical origin, their sector, and their individual commercial strategies. The common factors are, rst, that in the immediate aftermath of conict business people naturally will look for opportunities that combine relatively small capital investments with fast and preferably generous returns. Secondly, the companies most likely to operate in conict-affected environments are typically juniors (to adopt an oil industry term): smaller or less-established companies that follow a deliberate strategy of taking high risks in the hope of winning high returns.

John Bray

Variations by place of origin

Many analyses of private sector development distinguish between local and international business as though there were a clear divide between them.13 In practice, one should think more of a spectrum with small, parochial operators at one end and truly transnational companies at the other end. Arguably, most companies operating in post-conict zones are somewhere in the middle: even local companies typically benet directly or indirectly from international trading connections and sources of nance, while

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

international companies of course need to deal with local suppliers and sub-contractors. In this respect, the pattern of peacetime business is similar to the pattern of war. Pugh and Cooper have argued for the need to understand war economies as regional rather than purely national or local phenomena.14 The same applies to economies in recovery.

Local businesses

Local entrepreneurs have the strongest possible motivation to set up businesses. As one successful Bosnian businessman explained to this author in 2003, his original motivation was very simple: the war had ended, his country was in ruins, and he was hungry.15 Major constraints of course included limited access to nance and, in many cases, commercial expertise. Although business people who are based inor come fromconict-affected countries have a strong personal motivation to assist with its recovery, they will not put their own funds at risk unless they are reasonably condent of receiving a return. As Collier points out, wartime economies are characterised by capital ight, and this may continue even after the formal cessation of hostilities.16 Local conditions, at least in the short-term, may not be radically different from the situation during wartime.

Diaspora investors

Diaspora investors have the potential to play a particularly important role. More than most international operators, they have the local connections and, in many cases, the personal motivation to contribute to their countrys reconstruction. While living abroad, they may have picked up valuable expertise, in addition to amassing funds. In Afghanistan, the two rst mobile telephone companies both had diaspora connections: Afghan Wireless Communications Company is a joint venture between the

Private sector actors

Afghan Ministry of Communications (20 per cent) and the US company Telecommunications Systems International (TSI), which owns 80 per cent.17 TSI was founded by Ehsan Bayat, a US-based entrepreneur who was born in Kabul but left for the US in the 1980s. Roshan, the rival Afghan mobile phone company, is a consortium led by the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development (AKFEED), which owns 51 per cent together with a consortium of international investors.18 The Aga Khans Ismaili community is widely dispersed across Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia and AKFEED is widely respected for its development initiatives. In 2007 these two phone companies were joined by a third investor, the South Africa-based MTN.19 While diaspora investment can play an important role, it cannot be taken for granted. The World Banks 2005 report on the Investment Climate in Afghanistan noted that the total wealth of the Afghan diaspora was estimated at some ve billion US dollars, much of it in Dubai.20 Returnees had played an important role and, in addition to their access to capital, typically had higher levels of education than business leaders who had never left the country. However, at least initially, Afghanistan had less success than hoped in attracting funds from overseas Afghans. The local connections of diaspora investors are not necessarily unproblematic. They benet from local knowledge andoften by necessitymay be willing to operate in the informal economy. At the same time, knowing how to operate and dealing with the right people may simply imply a willingness to compromise business standards, for instance by paying bribes to powerful local gures.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Regional players

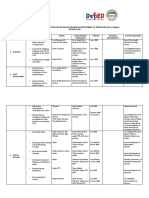

Regional players are somewhat similar in that they too benet from local connections and sources of knowledge. Regional geographical expansion often ts into their strategic plans, and they may believe that greater familiarity with local conditions gives them a comparative advantage over the major international players. Bosnias FDI portfolio is an example. Austria is the leading foreign investor by far, and this ts in with a wider pattern of Austrian investment in South-Eastern Europe. Austrian retail banks have played a particularly important role in supporting local economic recovery. After Austria, the next three leading investor countries are all former Yugoslav states (see Figure 1): Serbian investment, in particular, jumped dramatically in 2007.

John Bray

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Figure 1. Leading FDI stocks in Bosnia and Herzegovina as at December 2007 (em) Source: Data from the BiH Foreign Investment Promotion Agencywww.pa.gov.ba

Afghanistan shows a slightly different pattern: by late 2005 Turkey accounted for more than a fth of ofcially recorded foreign investment which by then amounted to some US$520m, followed by the US with 17 per cent and China and the UAE with less than 10 per cent each.21 Like Austria in South-Eastern Europe, Turkey appears to be playing an important role as an expanding regional economy, exploiting a comparative advantage by operating in relatively high-risk regions in Central Asia. Many of the US investors may in fact be diaspora Afghans. Afghanistans two leading traditional trading partners account for only ve per cent each of ofcially recorded investment. However, this may be because rms from these countries are more willing to operate in the informal economy.

Major transnational companies

Truly global companies with international reputations to defend are unlikely to take the risk of investing in a small and dangerous market unless they see commensurate global opportunities. As will be seen, the extent to which they identify such opportunities depends, in part, on the sector to which they belong.

Private sector actors

Variations by sector

Industry variables include the scale of the investment needed, the means of getting paid and the speed of return.22 The following examples illustrate the differences. Mobile phone companies, like the rst swallow of spring, are typically among the rst to invest in conict-affected areas, even before ceaseres. There are several reasons for this. First, the scale of investment for mobile phone networks is relatively low (often in the low hundreds of thousands of dollars in the rst instance). Secondly, returns are fast: the

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

operating companies start getting a return when the rst subscriber makes the rst call. The third reason is that many developed markets are already reaching maturity. By contrast, in war-impeded economies such as the DRC, there may be a pent-up demand for mobile phones. Construction companies are among the most active in a post-war setting because of the obvious need for their services and becausein the case of international companiesthey are typically paid offshore and, to that extent, can claim a degree of nancial and contractual security. However, companies often hesitate to make long-term investments, for example in the managementas distinct from the constructionof utilities, until they are more condent of the political and security environment. Transport and logistics companies in Afghanistan provide an interesting case study of a sector where entrepreneurs have been able to exploit a rst-mover advantage by providing an essential service with little initial competition and low start-up costs. According to a benchmarking study produced by the World Banks Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA),23 many logistics companies were able to begin with a modest investment of a few thousands or tens of thousands of dollars, often operating from a single-room ofce or a hotel, and have been able to make hundreds of thousands or millions in return. Prot margins will fall as conditions improve and competitors enter the market, but the wellestablished rst movers will continue to enjoy a strong advantage over their competitors. Petroleum and mining companies go where the minerals are. Many of the most attractive under-explored new opportunities are in hitherto conict-affected areas: the DRC is an obvious example for mining. Extractive industry companies are therefore typically among the rst to enter conict-affected countries, sometimes includingnotably in the case of the DRC in the late 1990s and early 2000scountries that are still at war. However, in the rst instance they are more likely to engage in exploration rather than the substantial investments needed to build and develop mines or oil elds. Also, the companies that enter

10

John Bray

high-risk environments are more likely to be small companies that offer their own investors high risks in the hope of high returns. Behemoths such as BP, Shell, Exxon or Rio Tinto are much more sensitive to risks to their reputation because they have more to lose. Much of the debate on the political economy of conict has focused on the impact of companies in the natural resources sectors, particularly petroleum and mining. In the worst case, oppressive national governments may use income from natural resources to reinforce their authorityand nance their armed forceswithout the need for accountability to taxpayers. Meanwhile rebel movements in countries such as Angola and Sierra Leone have used what have been called conict diamonds, to nance their military activities.24 A further concern is the debate about the so-called resource curse, the pattern of which seems to suggest that an abundance of natural resources distorts and impedes national economic development rather than enhancing it.25 Prominent examples that seem to support the curse theory include Nigeria under former President Sani Abacha and Zaire (now DRC) under President Mobutu Sese Seko. The major Western international companies are sensitive to these controversies and, as will be seen below, leading industry associations are trying to address them. At the same time there has, in recent years, been a trend in which state-owned companiesnotably from China, India and Malaysiainvest in high-risk regions where major Western companies are reluctant to operate: Sudan is the classic example. The motivation is often partly strategicinspired by their governments determination to gain access to important resourcesrather than narrowly commercial. Long-term initiatives to address the extractive sectors potential impact on conict need to involve both Western and non-Western companiesas well as businesses operating in other sectors. Banks are among the building blocks of economic development but tend to be risk-averse. Retail banks are less likely to invest until they are condent of a degree of political and regulatory stability. Standard Chartered Bank does have a record of setting up in high-risk environments: it was among the rst international banks to open branches in post-conict Sierra Leone and Afghanistan. That is, in part, because an important part of its client base comes from diplomats and development specialists. At least in the early stages of post-conict development, retail banks typically hesitate to build up their local client base too rapidly. Hotels follow a somewhat similar pattern: Hyatt set up an operation in Kabul soon after the fall of the Taliban in the hope of serving the diplomatic and aid ofcial market.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Private sector actors

11

Mass tourismwhich is notoriously susceptible to security concernstends to develop much later.

Speed and sequencing

It follows from the above that there is a natural sequencing pattern, both in the

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

quantity of foreign investment and in the form that it takes. Immediately after a ceasere, there tends to be a substantial increase in aid, but this tails off over the following decade as the memory of the conict recedes and aid fatigue sets in.26 The pattern of foreign direct investment (FDI) is somewhat different: there may be a slight increase in investment ows immediately after the conict, chiey from those seeking a rst-mover advantage and those engaged with physical reconstruction. The rst steps will most likely be taken by smaller and less risk-averse companies in sectors such as mobile phone sellers that have a realistic chance of making rapid returns. However, the major increase is likely to come some years after the conict has ended once the infrastructure has been repaired, the necessary institutions are in place and it is clear that the conict is not likely to resume. At this stage, retail banks and companies in sectors that require substantial initial investments are more likely to take the plunge. If all goes well, private investment will replace aid as the economy graduates from conict. Figure 2 illustrates that Bosnia-Herzegovina has followed roughly this pattern after a particularly slow start: a study of Bosnias economic reconstruction by Tzifakis and Tsardanidis refers to the rst 10 years after the Bosnian war as a lost decade.27 Bosnias prospects have always been limited by the fact that, with a total population of some four million, it constitutes a relatively small market. The factors that further delayed economic expansion in the post-war era included: the divisive political framework emerging from the 1995 Dayton Agreement; a complex and poorly structured regulatory system; the slow pace of privatisation; high levels of corruption; and the countrys post-socialist legacy as exemplied by the continuation of the socialist-era Payment Bureaux until 2001.28 The countrys reform programme began to pick up only in the early 2000s and eventually brought important results. For example, the abolition of the Payment Bureaux paved the way for the expansion of the retail banking industry, notably including substantial investments from foreign banks.

12

John Bray

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Figure 2. Bosnia and Herzegovina: ODA ows compared with FDI (US$m). Source: Data on aid receipts from Tzifakis and Tsardanidis, Economic Reconstruction for Bosnia and Herzegovina, 22; and OECD Journal on Development: Development Co-operation2007 Report, 193. Data on FDI from European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) country statistics, http://www.ebrd.com/country/sector/econo/stats/mptfdi.xls (accessed 10 December 2008). Despite its many problems, Bosnia-Herzegovina may be one of the more fortunate post-conict countries, beneting fromamong other advantagesits proximity to the European Union (EU). Many African countrieseven the more successful onesare less fortunate. Mozambique, whose civil war came to an end in the early 1990s, is regarded as one of the more successful post-conict countries but its recent ODA ows (US$1,611 million in 2006, according to the OECD) far outmatch FDI (US$154 million in 2006 according to UNCTAD).29 The gures for Uganda, another comparatively successful post-conict country, are similar: US$1,551 million in ODA in 2006, compared with only US$307 million in FDI.30 The recent aid/investment gures for the DRC, whose civil war came to an end in 2003, point to a dramatic inux of aid in the immediate aftermath of its peace agreement. In 2003, it received US$5.4 billion in ODA, followed by US$1.82 billion in 2004 and 2005.31 By contrast, FDI ows have been much slower. According to revised estimates by UNCTAD, FDI stocks actually contracted in 2005, although there was an inow of an estimated US$180 million in 2006.32 As elsewhere in Africa, mobile phone companies (including Vodacom and MTN from South Africa and Celtel from the Netherlands) have been well represented.33 There is no doubt of the DRCs mineral potential, so FDI in the mining industry is likely to be especially important. However, would-be investors face

Private sector actors

13

considerable political risks, as exemplied by the governments decision in 2007 to review 61 mining contracts that had been drawn up in the previous 10 years, and were considered to have been unduly advantageous to investors.34 The DRCs post-war political institutions are at best in a relatively early stage of development: it remains a classic case of a post-conict country that combines high political risks with the potential for high commercial returns. Against a background of renewed conict in eastern DRC in late 2008, it is too early to predict with condence how far private investment ows will be able to provide the country with the nancial resources that it needs.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Managing the private sector ecosystem

The 2004 UNDP report on Unleashing Entrepreneurship: Making Business Work for the Poor adopts a metaphor from the natural world when it refers in several places to the existence of a private sector ecosystem.35 In a similar vein, economic analysts often refer to a countrys investment climate, a term which the World Bank denes as the locationspecic factors that shape the opportunities and incentives for rms to invest productively, create jobs and expand.36 Certain climates favour particular commercial ecosystems that, as in the natural world, contain larger, smaller and micro-entities as well as predators, parasites and, no doubt, the equivalents of dung-beetles. The challenge is to create a symbiotic private sector ecosystem rather than a predatory one or, worse still, a commercial desert. In a post-conict setting it is particularly important to create job opportunities and improve livelihoods in rural areasand this as an area that is often neglected.37 The task of meeting these challenges demands the collaboration of a variety of actors: business and civil society as well as national and international policy-makers. In dening appropriate policies, there may be a role for certain kinds of aid conditionality, particularly if these are intended to avoid destructive economic patterns that increase the risk of a resumption of conict.38 However, particularly in conict-affected societies, the wide range of variables means that it is difcult to dene precise or predictable formulae. There is therefore no unique path to recovery based on the IMF or any other model.39 Nevertheless, certain patterns have begun to emerge.

14

John Bray

The central role of the state

The rst is the key role of the state in creating an enabling environment for the private sector. Few observers now favour the minute regulatory involvement characteristic of old-style socialist administrations. There is also a near-consensus among business people as well as ordinary citizens on the central role of the state in setting rules, particularly where these govern the provision of physical security, the rule of law, property rights and nancial frameworks.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Where national governments are unable to provide physical security, the continued presence of multinational security forcessuch as those co-ordinated by UN peacekeeping operations (UNPKO)is a matter of economic as well as political importance. However, investors understand as well asor better thanpoliticians that external intervention is at best a temporary solution pending the emergence of a viable political settlement. Similarly, the repair of physical infrastructure such as roads or electricity supplies is an important rst step to recovery. However, long-term economic as well as political recovery demands the creation of effective national institutions and regulatory frameworks. As the British economist Tony Addison puts it, it is a lot easier to pour concrete than to establish effective and accountable institutions.40 However, the latter is what is required to restore economic condence in post-conict environments. After the end of the Ugandan civil war in 1986, the Kampala Government took a series of steps to restore and reinforce property rights. This included returning property owned by Asians who had been expelled in 1972. At the time this was a painful measure because, in the meantime, the properties concerned had been occupied by local people. However, this approach brought results. By 1986 two thirds of Ugandan private wealth was held abroad and by the mid-1990s Uganda was attracting substantial repatriation, and this contributed to private sector investment in the countrys coffee boom.41 The key factors that make for a business-friendly enabling environmentnotably security, anti-corruption measures and the rule of laware as important to local entrepreneurs as they are to international companies. Indeed, World Bank research shows that small and informal rms often suffer more than medium and large companies from a poorly developed investment climate.42 Not surprisingly, small and informal rms nd it harder to obtain loans from a formal nancial institution. They are also less likely than

Private sector actors

15

larger rms to be condent that courts will uphold property rights, or to believe that regulations will be interpreted consistently. Local entrepreneurs and SMES play a particularly important role in post-conict recovery because, if all goes well, they are likely to provide one of the main sources of employment. Conversely, if they fail to benet, the legitimacy of the post-conict political order will come into question. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, there have been complaints that decisions on the award of reconstruction contracts tended to favour large international companies at the expense of local competitors. In the DRC one of the most sensitiveand potentially explosivequestions for the mining industry concerns the future status of artisanal miners. International advisors may be able to play a constructive role by advising on the most important reform measures. For example, the World Banks Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS) conducted diagnostic reviews of the investment climate in Sierra Leone and Liberia.43 Both reports emphasised the need for reforms to the local legal frameworks. External advisors have no mandate to engage in partisan political debate. What they can do is to help prepare the analysis and lay out the options on which national leaders must decide.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

The timing of reforms

Collier argues that there is an unparalleled opportunity for reform in the relatively uid period in the immediate aftermath of conict: it is important to seize it, and the Ugandan case study cited above is a positive example.44 In a similar vein, Mendelson-Forman and Mashatt refer to the golden hour, a term borrowed from the medical literature representing a crucial moment that could mean the difference between life and death for a critically ill patient.45 They argue that there is also a golden hour in the world of post-conict transformation whenearly on in the reconstruction processthe international community has the opportunity to lay a foundation for a full economic recovery from conict or to set the path for a recurrence of ghting.46 Whether, or not, one accepts the golden hour analogy, there is growing agreement on the need to embark on legal and regulatory reform sooner rather than later. Stating that this is desirable is not to underestimate the difculties. In interviews in Bosnia in 2003, this author encountered the view that earlier reform would have been difcult or impossible

16

John Bray

in the fraught political conditions of the mid- to late 1990s.47 A counter-argument is that it is harder to implement reforms later on because delays make it easier for those with post-conict vested interests to entrench their positions. With both local and international investors in mind, Schwartz and Halkyard therefore argue for the need to eliminate as many regulatory risk barriers to entry as possible; and avoid complex bidding arrangements meant to maximize the revenues from licenses, concessions or asset sales.48 The priority is to create a regulatory environment that promotes private investment, competition and consumer benets.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Promoting FDI

As discussed above, the pace of FDI is likely to be relatively slow in the immediate aftermath of conict, and this raises the question what can be done to accelerate it. The most important measures are the same as for domestic investors: legal institutional and regulatory reform to improve the security of property rights. At the same time there is a continuing debate on the extent to which special incentives may play a role in attracting foreign investment. In a discussion on the role of tax incentives in attracting FDI, Morisset argues that tax incentives are less important than such factors as basic infrastructure, political stability and the cost and availability of labour.49 This is not to say that they are irrelevant: tax incentives affect the decisions of some investors some of the time.50 They may be among the instruments that host governments can include in their portfolio, but are by no means the only tool that they have to attract FDI, much less the most important one. This general truism will apply all the more in post-conict environments. A similar point applies to political risk insurance (PRI). In a 2004 study on Bosnia, I argued that PRI was most useful in cases where the post-conict environment had improved, and investors had already identied attractive opportunities.51 In those circumstances, PRI could help tip the balance between risk and opportunity in favour of going ahead with investment. It therefore made the greatest difference in the early 2000s, by which time this tipping point was in sight, rather than in the mid- to late 1990s when the overall environment was too risky, or the mid-2000s by which time many of the worst problems had already been solved.

Private sector actors

17

In the Bosnian case PRI provided by MIGA was particularly useful in facilitating investment by Austrian retail banks, whose local branches were then able to serve as a source of credit to emerging local companies. MIGA has sought to play a similar role in Afghanistan through the Afghanistan Investment Guarantee Facility (AIGF). The facility includes features that are designed to facilitate the development of the local private sector. For example, a portion of AIGF can be used to insure transactions that involve loans by a foreign nancial institution or the local branch of a foreign bank to local Afghan businesses.52 The objective is to foster a commercial ecosystem in which international and local enterprises complement each other.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

The private sector and peacebuilding

Overall, the most important contribution that companies can make to peacebuilding is to concentrate on the responsible fullment of their core commercial activitieswhether these concern telecoms, nancial services or mineral developmentthus increasing wealth and creating the economic conditions for post-conict recovery. However, wealth creation is not in itself sufcient to resolve conict: indeed it may actually help create the conditions for conict if the benets of short-term economic recovery are unevenly distributed. The question therefore arises whether companies can do more to contribute to peacebuilding. In recent years, there has been increased emphasis on the need for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) or, to use the term favoured by the OECD, Responsible Business Conduct (RBC). Whatever term is used, it should be clear that the responsible business agenda must cover companies mainstream commercial activitiesfor example their treatment of employees and the consequences of their engagement with government agenciesand not just well-meaning but peripheral philanthropic sponsorships.

Business responsibility in weak governance zones

The challenges of conducting business responsibly are all the greater in countries and regions where governance standards are poor: these obviously include countries that have beenor still areaffected by conict. The OECD has drawn up a Risk Awareness Tool for

18

John Bray

Multinational Enterprises in Weak Governance Zones, and this emphasises the need for heightened managerial care including, for example, extra measures to ensure that companies are fully briefed on the backgrounds and connections of their business partners.53 Both the Risk Awareness Tool and the OECDs Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises are voluntary for companies, as are the UN Global Compacts ten principles.54 In recent years, NGOs in particular have called for binding international regulation to govern the activities of international companies.55 Signicant progress has in fact been made in the eld of anti-bribery legislation: all OECD member states now have laws establishing extraterritorial jurisdiction over companies from their countries that pay bribes to foreign ofcials, whether the bribe is paid at home or abroad.56 The 2003 UN Anti-Corruption Convention has established the foundations of a truly global anti-corruption regime. By contrast, progress in other eldsnotably human rightsremains slow. In June 2008 John Ruggie, the UN Secretary Generals Special Representative on Business and Human Rights, presented a report entitled Protect, Respect and Remedy to the UN Human Rights Council.57 Ruggie emphasises the need both for business to respect human rights and for states to protect potential victims. However, he has stopped short of calling for an international treaty on business and human rights, partly because of the difculties in enforcing it.58 In practice, voluntary initiatives and international regulation canand shouldcomplement each other rather than being seen as opposites.59

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

The need for conict sensitivity

In any case, regardless of the state of the international legal regime, companieslike public-sector agencieshave an enlightened self-interest in ensuring that their projects and policy interventions reduce the risk of conict rather than exacerbating it. The oil, gas and mining industries have come under particular scrutiny both in relation to the possibility that they coulddirectly or indirectlyhelp nance conict and because of their wider developmental impacts. Extractive industry companies typically spend millions of dollars on exploration, with uncertain returns, but once projects come into production the prots are enormous. However, there are limited employment opportunities for local people, particularly in regions with low educational standards. The main beneciaries all too often turn out to be national governments and companies rather than the local communities

Private sector actors

19

that suffer most from environmental impacts. The local conicts associated with the petroleum industry in Nigerias Niger Delta are now regarded as a classic illustration of negative social impacts: the challenge for petroleum and mining companies is to learn from painful past experiences and to avoid similar scenarios in future. By contrast, the business modeland the social impactsof the mobile phone industry are completely different. As noted above, initial investments are lower, nancial returns are faster and, of course, the local customer base is much wider. Mobile phones assist micro-entrepreneurs, for example, by making it easier to check market prices. In doing so, they make a contribution to broad-based economic development which may genuinely alleviate the risks of conict. Many of the most important lessons for business derive from the experience of development agencies. In her groundbreaking book Do No Harm, Mary B. Anderson focussed on the role of aid organisations. Since then, she and her colleagues have adapted many of the principles that she developed for aid agencies to the private sector.60 She points out that in conict situations, companies can hardly expect to be neutral. There are always winners and losers. Almost everything that companies do will have an impact on the underlying conict one way or another. It is therefore important to identify connectorsactions and projects that will bring people together rather than dividing them. Employment is often a particularly sensitive issue in terms of who benets most from job opportunities and where they come from. Both aid agencies and companies need to design their recruitment policies accordingly. Specically with regard to the private sector, the United Kingdom-based NGO International Alert likewise has been promoting the principles of conict sensitivity, initially with a particular focus on the extractive sectors. Publications include a Conict-Sensitive Business Practice Toolbox for Extractive Industries, and a follow-up publication for engineering contractors.61 The principles of conict-sensitive business practices and development are becoming better and better understood: the major challenge is how to implement them most effectively. Within companies, one of the biggest challenges is to ensure that they are understood and fully applied by operations managers and not just by CSR specialists. More broadly, there is an obvious need to ensure that the principles of conict sensitivity are applied not just by larger Western companies but also by smaller and niche companies from all parts of the world, as well as by local entrepreneurs. This dissemination process is only just beginning.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

20

John Bray

Collective business initiatives

Collective business initiatives play an important role in helping to raise standards and promote best practice, both internationally and locally. Examples with a bearing on post-conict development include the banks that have adopted the Equator Principles, a set of guidelines for making project nancing decisions.62 These include a commitment to adopt the International Finance Corporations (IFC) social and environmental performance standards when making project nancing decisions. Meanwhile, the UNs

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Global Compact initiative has played an important role both in giving advice on the principles of conict risk assessment, and in promoting public-private policy engagement on how to promote responsible business in conict-affected areas.63 At the same time, industry associationssuch as the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA)are producing their own guidance documents for companies operating in conict zones.64 Collective business initiatives can also play a valuable advocacy role at the local level. Individual business peoplesuch as those in the former Yugoslav successor states frequently complain of a lack of understanding by local and national administrations. In the former Yugoslav states, this is the legacy not so much of conict as of the socialist era that preceded the conict. Rather than taking the measures needed to stimulate business in the rst place, overstaffed local administrations have placed more emphasis on raising taxes to ensure that they have sufcient income to avoid town-hall redundancies. Part of the answer may come from the development of genuinely representative business associations that are better placed to articulate private sector concerns and propose solutions.65 SMEs are often under-represented in political dialogues on governance and economic reforms, in part because the associations that represent them are poorly organised and have limited political clout. In its 2006 assessment of Liberias post-war investment prospects, the FIAS pointed to the need for a transparent and institutionalised process to establish dialogue between the government and the private sector.66 Existing Liberian business associations tended to be aligned on both ethnic and sectoral lines and many appeared to face internal governance problems. In research visits to Montenegro and Georgia (both of which are transitional andat least to some extentconict-affected economies) conducted on behalf of the US development agency CHF International in 2006, this author was struck by the comparative neglect of the agricultural sector.67 The reasons in part seemed to stem from the priorities

Private sector actors

21

of the metropolitan elites leading the two countries national administrations. Both there and in many other countries the agricultural sector is poorly represented in national policy discussions, and this is all the more damaging for the obvious reason that it provides one of the main sources of livelihoods in rural areas.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Business and conict resolution

While the prime role of companies is to concentrate on their core businesses, there may be questions concerning their ability to play a more explicit part in conict resolution. These questions are sensitive ones. It is understood that business associations are entitled to lobby governments concerning, for example, tax regimes. However, neither individual companies nor business associations can make a plausible claim to a democratic mandate, and it is therefore questionable whether they can claim the popular legitimacy needed to justify a wider political involvement. In the worst case, they run the risk of being accused of attempting regime capturedistorting the political process in order to advance the personal interests of elites who hold narrow views of their political and economic responsibilities. In this sense, regime capture was, for example, a feature of Slobodan Milosevics Serbia. However, while such warnings need to be taken seriously, there are positive examples of business playing a constructive peacebuilding role. One case comes from Northern Ireland, where the local branch of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) made an important contribution by spelling out the economic consequences of conict to rival leaders, and introducing the notion of a piece dividend into the local political vocabulary. 68 Similarly, in the early 1990s South African business helped facilitate the transition from the apartheid regime to democracy by fostering communications between rival political parties.69 In Colombia business-led peace initiatives have made an important contribution at the local level: for example, by changing to a co-operative business model, promoting public policy dialogue and championing sustainable development in deprived areas in an attempt to address the economic sources of conict.70 Business is most effective when it avoids the appearance of partisanship in the sense of supporting one particular actor or political party, but instead points to the economic costs of failing to end conictand to the dividends that accrue from achieving peace.

22

John Bray

Policy implications: changing paradigms

War is the ultimate zero-sum game: winners take all, often including the lives as well as the livelihoods of their opponents. By contrast, the paradigm for a sustainable business is a series of repeatable transactions from which both sides benet. The winner-takes-all paradigm does not disappear when a peace treaty is signed. War is politics by other means: all too often politics is war by other means. In this sense economics also may be a form of war: the political control of economic resources to favour particular communities or individual rent-seekers at the expense of the wider community. The Afghan warlords dominance of local trading networks is one example. The ethnic-political-commercial nexus that controlled parts of Bosnia long after the ghting ended is another; and the continued inuence of Kosovos underground networks supported by political interests is a third example. The ultimate objective of economic policy-makers must be to change the war paradigm in favour of a model of business engagement that is based on co-operation rather than conict, and that is therefore truly sustainable. In order to achieve this shift, government policy-makers and development specialists need to factor private sector concerns into their calculations at every stage. This requires a nuanced view of the many different kinds of private sector actors, including their approaches to risk, the ways that they interact and their various contributions to economic recovery. Perhaps the most important single requirement is to focus on the rule of law and the development of an equitable regulatory environment at the earliest possible moment, and not as an afterthought once the reconstruction of physical infrastructure is under way. Meanwhile, companies themselves need to take a more sophisticated view of their own contributions to peacebuilding, learning from the development agencies soul-searching on the need for conict sensitivity in all aspects of economic development. Finally, all parties require a hard sense of realism. Private sector actors are neither the source of all ills nor the solution to all dilemmas. Private sector development can alleviate some post-conict problems, and no lasting economic recovery is possible without it. At the same time, it needs to be remembered that peace processes are inherently and inevitably political. Skilful economic initiatives can supportbut not replacethe political process.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Private sector actors

23

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a background paper commissioned by the United Nations Development Programme in connection with its report, Post-Conict Economic Recovery: Engaging Local Ingenuity, Crisis Prevention and Recovery Report 2008, UNDP Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery, New York. I am particularly grateful Karen Ballentine, who commissioned the original paper, and to an anonymous Conict Security and Development reviewer for their advice and suggestions. I retain responsibility for all errors of fact or judgement.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Endnotes

1. On the potential complexities of aid impacts see Anderson, Do No Harm. 2. Barbara, Nation Building and the Role of the Private Sector, 591. 3. Pugh, Post-war Economies. 4. Bray, Public-private Partnership, 2. ndu z and Killick, Local Business, Local 5. Baneld, Gu Peace, 2. 6. Nenova and Harford, Anarchy and Invention, 2. 7. See, for example, Berdal and Malone, Greed and Grievance; Collier and Hoefer, Greed and Grievance in Civil War; Ballentine and Sherman, The Political Economy of Armed Conict; Berdal, Beyond Greed and ndu z and Killick, Local Grievance; and Baneld, Gu Business, Local Peace. Collier, Economic Causes of Civil Conict. 8. UN Panel of Experts, Letter Dated 15 October 2003. 9. For a review of DDR policy issues, see UNDP, PostConict Economic Recovery, 65 73. 10. Ohiorhenuan, Challenge of Economic Reform, 17. 11. Lister and Pain, Trading in Power, 1 2. 12. See Large, Corruption in Post-war Reconstruction; Le Billon, Buying Peace or Fuelling War; Galtung and , Integrity after War. Tisne ndu z and Killick, Local 13. See, for example, Baneld, Gu Business, Local Peace, 16 35. 14. Pugh and Cooper, War Economies in a Regional Context. 15. Interview conducted in Vitez, Central Bosnia, November 2003. 16. Collier, Post-conict Recovery, 7. 17. Bray, International Companies and Post-Conict Reconstruction, 14 15. 18. Ibid. 19. MIGA Supports Critical Telecommunications Investment in Afghanistan. Press release, 3 July 2007. Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, Washington. www.miga.org. 20. World Bank, Investment Climate in Afghanistan, 8. 21. Ibid., 9 22. For an extended discussion of these variations see Bray, International Companies and Post-Conict Reconstruction. 23. MIGA, Benchmarking FDI Opportunities, 30. 24. Bannon and Collier, Natural Resources and Violent Conict. 25. For an authoritative review of the resource curse debate see Stevens, Resource Impact. 26. Collier, Aid Policy and Growth; Collier et al., Breaking the Conict Trap, 167 170; Schwartz, Hahn and Bannon, The Private Sectors Role. 27. Tzifakis and Tsardanidis, Economic Reconstruction for Bosnia and Herzegovina. 28. Bray, MIGAs Experience in Conict-Affected Countries, 13 20. 29. OECD Journal on Development: Development Co-operation2007. Report, 190; UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2007, 252. 30. Ibid. 31. OECD Journal on Development: Development Co-operation2007 Report, 190. 32. UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2007, 252. 33. OReilly, Finbarr, 2002. Mobile Phone Networks Battle for Congos market. News24.com . Available at: www.news24.com (accessed 3 February 2008). 34. Bream, Rebecca, 2008. Congo Asks for Bigger Mining Share. Financial Times, 20 March 2008. 35. UNDP, Unleashing Entrepreneurship. 36. World Bank, Better Investment Climate, 1. 37. For a discussion of this point in relation to Timor Leste see Kusago, Post-Conict Pro-poor Private Sector Development. 38. Boyce, Investing in Peace. 39. See the chapter on Macroeconomic Policy Considerations in Post-Conict Recovery in UNDP, Post-Conict Economic Recovery. 40. Addison, Understanding Investment in Post-Conict Settings. 41. Collier, Post-conict Recovery. 42. World Bank. Better Investment Climate, 8 43. FIAS, Sierra Leone; FIAS, Liberia.

24

John Bray

ndu z and Nick, Killick, (eds.), Baneld, Jessie, Canan, Gu 2006. Local Business, Local Peace: The Peacebuilding Potential of the Domestic Private Sector. International Alert, London. Baneld, Jessica and Salil, Tripathi, 2006. Conict Sensitive Business Practices: Engineering Contractors and Their Clients. International Alert, London. Bannon, Ian and Paul, Collier (eds.), 2003. Natural Resources and Violent Conict: Options and Actions. World Bank, Washington DC. Barbara, Julien, 2006. Nation Building and the Role of the Private Sector as a Political Peace-Builder. Conict, Security & Development 6(4), 581 594. Berdal, Mats, 2005. Beyond Greed and Grievanceand not too soon. . . . Review of International Studies 31(3), 687 698. Berdal, Mats and David, Malone (eds.), 2000. Greed and Grievance: Economic Agendas in Civil Wars. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, CO. Boyce, James K., 2002. Investing in Peace: Aid and Conditionality after Civil Wars. Adelphi Paper 351. International Institute for Strategic Studies, Oxford. Bray, John, 2004. MIGAs Experience in Conict-Affected Countries. The Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. CPR Working Papers, no. 13. World Bank (Conict Prevention and Reconstruction Unit), Washington DC. Bray, John, 2005. International Companies and Post-Conict Reconstruction: Cross-sectoral Comparisons. CPR Working Papers, no. 22. World Bank (Conict Prevention and Reconstruction Unit), Washington DC. Available at: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/ default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2005/03/30/ 000012009_20050330161732/Rendered/PDF/31819.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Bray, John, 2006. Public-private Partnership in Statebuilding and Recovery from Conict. International Security Programme Brieng Paper, 06/01. Royal Institute for International Affairs, London. Available at: www.chathamhouse.org.uk (accessed 3 February

44. Collier, Post-conict Recovery, 6 7. 45. Mendelson-Forman and Mashatt, Employment Generation and Economic Development, 3. 46. Ibid., 3. 47. Bray, MIGAs Experience in Conict-Affected Countries, 40. 48. Schwartz and Halkyard. Rebuilding Infrastructure, 2. 49. Morisset, Tax Incentives, 1. 50. Ibid. 51. Bray, MIGAs Experience in Conict-Affected Countries, 41 42. 52. MIGA, Afghanistan Investment Guarantee Facility.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

53. OECD, Risk Awareness Tool. 54. OECD, Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises; UN, Global Compact Business Guide. 55. See Turner, Taming Mammon. 56. Bray, Facing up to Corruption. 57. Ruggie, Protect, Respect and Remedy. 58. Ruggie, Business and Human Rights. 59. Gordon, Rules for the Global Economy. 60. For more information, see: www.cdainc.com. 61. International Alert, Conict-Sensitive Business Practice Toolbox; Baneld and Tripathi, Conict Sensitive Business Practices. 62. For more information, see www.equator-principles.com 63. UN Global Compact, Global Compact Business Guide; UN Global Compact, Enabling Economies of Peace. 64. IPIECA, Operating in Areas of Conict. 65. Bray, CHFs Municipal and Economic Development Initiative (MEDI) Project. 66. FIAS, Liberia. 67. USAID, Economic Civil Society Organizations in Democracy-Building, 61 63. 68. International Alert, The Confederation of British Industry. 69. Charney, Civil Society, Political Violence, and Democratic Transitions. 70. Rettberg, Business-led Peacebuilding in Colombia.

References

Addison, Tony, 2006. Understanding Investment in PostConict Settings. Notes for a presentation at GTZ conference Private Sector Development and Peace building, 14-17 September 2007. Available at: http:// www.bdsknowledge.org/dyn/be/docs/108/Addison_PC_ Investment.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Anderson, Mary B., 1999. Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peaceor War. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, CO. Ballentine, Karen and Jake, Sherman, 2003. The Political Economy of Armed Conict: Beyond Greed and Grievance. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, CO.

2009). Bray, John, 2006. CHFs Municipal and Economic Development Initiative (MEDI) Project: A Case Study in Local and Regional Peacebuilding in Central Bosnia, in Local Business, Local Peace: The Peacebuilding Potential of the Domestic Private Sector, eds. Jessie, Baneld, Canan ndu z, and Nick, Killick. International Alert, London, Gu 257 261. Bray, John, 2007. Facing up to Corruption 2007: A Practical Business Guide. Control Risks, London. Available at: http://www.control-risks.com/pdf/Facing_up_to_cor ruption_2007_englishreport.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009).

Private sector actors

Charney, Craig, 1999. Civil Society, Political Violence, and Democratic Transitions: Business and the Peace Process in South Africa, 1990 to 1994. Comparative Studies in Society and History 41(1), 182 206. Collier, Paul, 2006. Economic Causes of Civil Conict and their Implications for Policy. Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, Oxford University, Oxford. Available at: http://users.ox.ac.uk/~econpco/ research/pdfs/EconomicCausesofCivilConict-Implica tionsforPolicy.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Collier, Paul, 2007. Post-conict Recovery: How should Policies be Distinctive?. Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, Oxford University, Oxford. Available at: http://users.ox.ac.uk/ ~econpco/research/pdfs/PostConict-Recovery.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Collier, Paul and Anke Hoefer, 2001. Greed and Grievance in Civil War. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, no. 2355. World Bank, Washington DC. Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS), 2004. Sierra Leone: Diagnostic Study of the Investment Climate and the Investment Code. FIAS, Washington DC. Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS), 2006. Liberia: Mini Diagnostic Analysis of the Investment Climate. FIAS, Washington DC. , 2008. Integrity after Galtung, Fredrik and Martin, Tisne War: Why Reconstruction Assistance Fails to Deliver to Expectations. Unpublished research paper. TIRI, London. Gordon, Kathryn, 1999. Rules for the Global Economy: Synergies between Voluntary and Binding Approaches. OECD Directorate for Financial, Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs Working Papers on International Investment, no. 1999/3. OECD, Paris. Available at: http://titania. sourceoecd.org/vl 7444899/cl 20/nw 1/rpsv/cgibin/wppdf?le 5lgsjhvj8vhd.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). International Alert, 2005. The Conict-Sensitive Business Practice Toolbox for Extractive Industries. International Alert, London. International Alert, 2006. The Confederation of British Industry and the Group of Seven: A Marathon Walk to Peace in Northern Ireland, in Jessie Baneld, Canan ndu z, and Nick Killick (eds.), Local Business, Local Gu Peace: The Peacebuilding Potential of the Domestic Private Sector, International Alert, London, 438 443. International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA), 2008. Operating in Areas of Conict: An IPIECA Guide for the Oil and Gas Industry. IPIECA, London.

25

Kusago, Takayoshi, 2005. Post-conict Pro-poor Privatesector Development: the Case of Timor Leste. Development in Practice 15(3/4), 502 513. Large, Daniel (ed.), 2005. Corruption in Post-war Reconstruction: Confronting the Vicious Cycle. Lebanese Transparency Association, Beirut; TIRI, London. Available at: http://www.tiri.org/index.php?option com_content& task view&id 155 (accessed 3 February 2009). Le Billon, Philippe, 2003. Buying Peace or Fuelling War: The Role of Corruption in Armed Conicts. Journal of International Development 15(4), 413 426. Lister, Sarah and Adam, Pain, 2004. Trading in Power: The Politics of Free Markets in Afghanistan. Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit, Kabul. Available at: http://www.areu.org.af/index.php?option com_ content&task view&id 44&Itemid 109 (accessed 3 February 2009). Mendelson-Forman & Mashatt, M. 2007. Employment Generation and Economic Development in Stabilization and Reconstruction Operations. Washington: US Institute of Peace. Available at www.usip.org/pubs/spe cialreports/srs/srs6.pdf. Morisset, Jacques, 2003. Tax Incentives: Using Tax Incentives to Attract Foreign Direct Investment. Public Policy Journal, 253. Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), 2005. Benchmarking FDI Opportunities. Investment Horizons: Afghanistan. A Study of Foreign Direct Investment Costs and Conditions in Four Industries. MIGA, Washington DC. Available at: http://www.export.gov/afghanistan/ pdf/investment_horizons.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), 2005. Afghanistan Investment Guarantee Facility. MIGA, Washington DC. Available at: www.miga.org/documents/IGGafghan.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Nenova, Tatiana and Tim Harford, 2004. Anarchy and Invention: How does Somalias Private Sector Cope without Government?. Public Policy Journal, 280. World Bank, Washington DC. OECD, 2000. Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. OECD, Paris. Available at: www.oecd.org/dataoecd/56/36/ 1922428.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). OECD, 2006. Risk Awareness Tool for Multinational Enterprises in Weak Governance Zones. OECD, Paris. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/21/ 36885821.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). OECD, 2007. Development Cooperation Report 2007. OECD JournalonDevelopment 9(1), StatisticalAnnex.Availableat: http://puck.sourceoecd.org/pdf/dac/432008011e-06statisticalannex.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009).

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

26

John Bray

Tzifakis, Nikolaos and Charalambos, Tsardanidis, 2006. Economic Reconstruction for Bosnia and Herzegovina: The Lost Decade. Ethnopolitics 5(1), 67 84. UN Conference on Trade Development, 2007. World Investment Report 2007. New York and Geneva: UNCTAD. Available at: http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/ wir2007-en.pdf. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2004. Unleashing Entrepreneurship: Making Business Work for the Poor. Commission on Private Sector Development report to the Secretary General of the United Nations. UNDP, New York. Available at: www.undp.org/cpsd/ report (accessed 3 February 2009). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2008. Post-Conict Economic Recovery: Engaging Local Ingenuity. UNDP Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery, New York. Available at: www.undp.org/cpr/we_do/ eco_recovery.shtml (accessed 3 February 2009). UN Global Compact, 2002. Global Compact Business Guide for Conict Impact Assessment and Resource Management. UN, New York. Available at: www.unglobal compact.org/docs/issues_doc/7.2.3/BusinessGuide.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). UN Global Compact, 2005. Enabling Economies of Peace: Public Policy for Conict-Sensitive Business . UN, New York. UN Panel of Experts, 2003. Letter Dated 15 October 2003 from the Chairman of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of Congo Addressed to the Secretary-General, United Nations Security Council. S/2003/1027. Available at: www.un.org/Docs/ journal/asp/ws.asp?m=S/2003/1027 (accessed 3 February 2009). USAID, 2007. Economic Civil Society Organizations in Democracy-Building: Experiences from Three Transition Countries. PVC/ASHA Research APS AFP-G-00-0500012-00. Submitted by CHF International. USAID, Washington DC. World Bank, 2004. A Better Investment Climate for Everyone. World Bank Development Report. World Bank and Oxford University Press, Washington DC and New York. World Bank, 2005. The Investment Climate in Afghanistan: Exploiting Opportunities in an Uncertain Environment. Finance and Private Sector Development Unit, South Asia Region. World Bank, Washington DC.

Ohiorhenuan, John, 2007. The Challenge of Economic Reform in Post-Conict Liberia: The Insiders Perspective. Background Paper for Post-Conict Economic Recovery: Engaging Local Ingenuity. Crisis Prevention and Recovery Report 2008. UNDP Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery, New York. Available at: www.undp.org/ cpr/content/economic_recovery/Background_5.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Pugh, Michael, 2006. Post-war Economies and the New York Dissensus. Conict, Security & Development 6(3), 269 290.

Downloaded by [Nagoya University] at 20:52 03 July 2012

Pugh, Michael and Neil, Cooper, with Jonathan Goodhand, 2004. War Economies in a Regional Context: Challenges of Transformation. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, CO. Rettberg, Angelia, 2004. Business-led Peacebuilding in Colombia: Fad or Future of a Country in Crisis. Final Report, Crisis States Programme. London School of Economics and Political Science, London. Available at: www.crisisstates.com/publications/wp/WP1/56.htm (accessed 3 February 2009). Ruggie, John, 2008. Protect, Respect and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and other Business Enterprises. A/HRC/8/5. UN Human Rights Council, Geneva. Ruggie, John, 2008. Business and Human rightsTreaty Road not Travelled. Ethical Corporation, London. Available at: www.ethicalcorp.com/content.asp?content id=5887 (accessed 3 February 2009). Schwartz, Jordan and Pablo, Halkyard, 2006. Rebuilding Infrastructure. Policy options for Attracting Private Funds after Conict. Public Policy Journal, 306, World Bank, Washington DC. Available at: http://rru.world bank.org/documents/publicpolicyjournal/306Schwartz_ Halykyard.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Schwartz, Jordan, Shelley, Hahn and Ian Bannon, 2004. The Private Sectors Role in the Provision of Infrastructure in Post-conict Countries. CPR Working Paper. Washington: World Bank. Stevens, Paul, 2003. Resource Impact: Curse or Blessing? A Literature Survey. CEPMLP Internet Journal 13(14). Available at: www.dundee.ac.uk/cepmlp/journal/html/ Vol13/article13-14.pdf (accessed 3 February 2009). Turner, Mandy, 2006. Taming Mammon: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Global Regulation of Conict Trade. Conict Security & Development 6(3), 365 387.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Modified Airdrop System Poster - CompressedDocument1 pageModified Airdrop System Poster - CompressedThiam HokNo ratings yet

- Assessment 4 PDFDocument10 pagesAssessment 4 PDFAboud Hawrechz MacalilayNo ratings yet

- What Are The Advantages and Disadvantages of UsingDocument4 pagesWhat Are The Advantages and Disadvantages of UsingJofet Mendiola88% (8)

- Module 2 TechnologyDocument20 pagesModule 2 Technologybenitez1No ratings yet

- SAP HR - Legacy System Migration Workbench (LSMW)Document5 pagesSAP HR - Legacy System Migration Workbench (LSMW)Bharathk KldNo ratings yet

- Vintage Airplane - May 1982Document24 pagesVintage Airplane - May 1982Aviation/Space History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Profibus Adapter Npba-02 Option/Sp Profibus Adapter Npba-02 Option/SpDocument3 pagesProfibus Adapter Npba-02 Option/Sp Profibus Adapter Npba-02 Option/Spmelad yousefNo ratings yet

- Transposable Elements - Annotated - 2020Document39 pagesTransposable Elements - Annotated - 2020Monisha vNo ratings yet

- Energy-Roles-In-Ecosystems-Notes-7 12bDocument10 pagesEnergy-Roles-In-Ecosystems-Notes-7 12bapi-218158367No ratings yet

- AMO Exercise 1Document2 pagesAMO Exercise 1Jonell Chan Xin RuNo ratings yet

- UBMM1011 Unit Plan 201501Document12 pagesUBMM1011 Unit Plan 201501摩羯座No ratings yet