Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Duty of Care

Uploaded by

SaurabhDobriyalCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Duty of Care

Uploaded by

SaurabhDobriyalCopyright:

Available Formats

Negligence

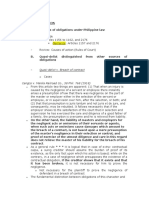

Introduction Negligence began to be recognised as a tor t in it s own right around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Before that time, the dominating action for personal injury was the writ of trespass. Trespass was initially concerned only with direct acts, however, during the nineteenth century the focus shifted to the distinction between intentional wrongs (trespass) and the unintentional (negligence). As we have seen, negligence was originally described in terms of a duty imposed by law and thus it will be seen that duty is one of the three ey elements of negligence today. Negligence evolved as a means of loss!shifting at a time when there was little or no insurance or state welfare provision. The industrial revolution in the nineteenth century brought with it increased ris s of injury to those wor ing in factories, mines, "uarries, and other dangerous situations. The development of railway transportation and mass production dramatically increased the potential for many people to be affected by the faulty conduct of strangers, at the same time that the development of incorporations meant that there would be a company to sue rather than an individual. The damage in such cases would have been personal injury or death and, to a lesser e#tent, property damage. What is Negligence? Negligence is when someone who owes you a duty of care has failed to act according to a reasonable standard of care and this has caused you injury. What is Duty of Care? The law says that if it is reasonably foreseeable that you might suffer some sort of harm or loss because of something someone else does, then that person owes you a duty of care. This duty of care is a reasonably comple# legal issue, but basically means that someone must act with a reasonable standard of care. $f this person does not follow their standard of care, and you suffer harm or loss as a result, then they have been negligent. %or e#ample, it is reasonably foreseeable that if the carer of a person with a disability did not act in the correct way, that the person with a disability might

suffer harm or loss. Therefore this carer would owe a duty of care not to injure the person with a disability.

The Elements of Negligence A number of elements have been established in order to prove the tort of negligence. %irstly, there must be a duty of care. &econdly, there must be a breach of this duty of care. Thirdly, there must be loss or damage and fourthly, there must be a causal lin between the breach of the duty of care and the loss or damage suffered. Negligence is the most common and therefore the most important of all the torts. %or the claimant to succeed in a negligence case, he will have to prove the following' ( The defendant owed a legal duty of care to the claimant. ) The defendant breached that duty. * The claimant suffered damage as a result of the breach of duty.

DUTY OF CARE The duty of care arises in the tort of negligence, a relatively recently emerged tort. Traditionally, actions in tort were divided into trespass and trespass on the case, or simply +case,. Trespass dealt with the situation where the injury was immediate, in other words direct and foreseeable. Actions based in case however, covered conse"uential injuries in the case of libel or deceit, etc. An underlying problem of this approach was that there was no fundamental principle or test that was applicable to a novel set of facts.

At common law, duties were formerly limited to those with whom one was in privity one way or another, as e#emplified by cases li e -interbottom v. -right ((./)). $n the early )0th century, judges began to recogni1e that the cold realities of the &econd $ndustrial 2evolution (in which end users were fre"uently several parties removed from the original manufacturer) implied that

enforcing the privity re"uirement against hapless consumers had harsh results in many product liability cases. The idea of a general duty of care that runs to all who could be foreseeably affected by one3s conduct Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 ( ! "c# %act' At about ..40 p.m. on )5 August (6)., 7rs 7ay 8onoghue (whose maiden name was 7 c,Alister) went to a cafe owned by %rancis 7 inchella, nown as the -ellmeadow 9afe, in -ellmeadow 2oad, :aisley. A friend of hers (probably a female friend) bought a bottle of ginger beer and an ice cream. The bottle was made of opa"ue glass. 7inchella poured part of the contents into a tumbler containing the ice cream. 7rs 8onoghue dran some of this and the friend then poured the remainder of the ginger beer into the glass. $t was said that a decomposed snail ;oated out of the bottle and the pursuer claimed that she suffered shoc and gastroenteritis, and as ed for <400 damages from the manufacturer of the ginger beer, 8avid &tevenson of :aisley. The pursuer claimed that a manufacturer of products was liable in negligence to a person injured by the product, but the defendant claimed that there could be no liability as there was no contract between him and the pursuer. The case went all the way to the =ouse of >ords and she won. el$' on the point of law involved, that such a defendant could be liable to such a claimant in negligence.

!egal %est for &in$ing out Whether a !egal Duty of Care '(ists

The legal test for finding out whether a legal duty of care e#ists, in any given situation, was first set out in the famous case of 8onoghue v &tevenson ((6*)). The Neighbour Principle A principle developed by >ord At in in the famous case of Donoghue v Stevenson ?(6*)@ A9 45) (=> &c) (&nail in the Bottle case) to establish when a duty of care might arise. The principle is that one must ta e reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions that could reasonably be foreseen as li ely to injure one3s neighbour.

>ord At in3s famous statement in the =ouse of >ords in the case of 8onoghue v &tevenson ((6*)) AThe rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbourB and the lawyer3s "uestion, 3who in law is my neighbourC, receives a restricted reply. Dou must ta e reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be li ely to injure your neighbour. -ho, then, in law is my neighbourC The answer seems to be ! persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that $ ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when $ am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in "uestion.A

%rom >ord At in3s statement it can be seen that in order for a duty of care to e#ist there must be reasonable foresight of harm to persons whom, it is reasonable to foresee may be harmed by your acts or omissions.

e$ley )yrne * Co !t$ + eller * ,artners !t$ AC -65 is an English tort law case on pure economic loss, resulting from a negligent misstatement. :rior to the decision, the notion that a party may owe another a duty of care for statements made in reliance had been rejected, with the only remedy for such losses being in contract law. The =ouse of >ords overruled the previous position, in recognising liability for pure economic loss not arising from a contractual relationship, introducing the idea of Aassumption of responsibilityA. &acts =edley Byrne was a firm of advertising agents. A customer, Easipower >td, put in a large order. =edley Byrne wanted to chec their financial position, and credit!worthiness, and subse"uently as ed their ban , National :rovincial Ban , to get a report from Easipower,s ban , =eller F :artners >td., who replied in a letter that was headed, A-ithout responsibility on the part of this ban A $t said that Easipower was, A9onsidered good for its ordinary business engagementsA

The letter was sent for free. Easipower went into li"uidation and =edley Byrne lost <(G,000 on contracts. =edley Byrne sued =eller F :artners for negligence, claiming that the information was given negligently and was misleading. =eller F :artners argued there was no duty of care owed regarding the statements, and in any case liability was e#cluded. .u$g/ent The court found that the relationship between the parties was Asufficiently pro#imateA (&pecial 2elationship) as to create a duty of care. $t was reasonable for them to have nown that the information that they had given would li ely have been relied upon for entering into a contract of some sort. This would give rise, the court said, to a Aspecial relationshipA, in which the defendant would have to ta e sufficient care in giving advice to avoid negligence liability. =owever, on the facts, the disclaimer was found to be sufficient enough to discharge any duty created by =eller3s actions. There were no orders for damages. Economic loss caused by negligent misrepresentation is recoverable where' a special relationship e#ists between the partiesB the defendant accepted responsibility in the circumstances of the adviceB and the plaintiff relied upon the misrepresentation

>ater, in the H.I., the law has developed certain categories of negligence, as suggested by >ord Bridge in Ca0aro 1n$ustries 0lc + Dic2/an ?(660@ ( All E.2. 45., when he stated that Jthe law should develop new categories of negligence incrementally and by analogy with established categories rather than by a massive extension of a prima facie duty of care restrained only by an indefensible consideration which ought to negative or reduce or limit the scope of the duty or the class of person to whom it is owed.K !34D 43"51!!6

$ agree with the fact that it has now to be accepted that there is no simple formula or touchstone to which recourse can be had in order to provide in every case a ready answer to the "uestions whether, given certain facts, the law will or will not impose liability for negligence or in cases where such liability can be shown to e#ist, determine the e#tent of that liability. :hrases such as Aforeseeability,A Apro#imity,A Aneighbourhood,A Ajust and reasonable,A Afairness,A Avoluntary acceptance of ris ,A or Avoluntary assumption of responsibilityA will be found used from time to time in the different cases. But, as your >ordships have said, such phrases are not precise definitions. At best they are but labels or phrases descriptive of the very different factual situations which can e#ist in particular cases and which must be carefully e#amined in each case before it can be pragmatically determined whether a duty of care e#ists and, if so, what is the scope and e#tent of that duty.

You might also like

- Negligence: Blyth V Birmingham WaterworksDocument17 pagesNegligence: Blyth V Birmingham WaterworksTee Khai ChenNo ratings yet

- Tort of NegligenceDocument8 pagesTort of NegligenceClitonTay100% (2)

- NegligenceDocument8 pagesNegligenceanon-964107100% (2)

- Law of NegligenceDocument16 pagesLaw of NegligenceSufyan SallehNo ratings yet

- Chapter 08 - Dangerous PremisesDocument68 pagesChapter 08 - Dangerous PremisesMarkNo ratings yet

- Standard of Duty of CareDocument20 pagesStandard of Duty of CareYasharth TripathiNo ratings yet

- Occupiers Liability Version 11Document7 pagesOccupiers Liability Version 11Dickson Tk Chuma Jr.No ratings yet

- Negligence in Australia Legal OutlineDocument20 pagesNegligence in Australia Legal OutlineLocky O'RourkeNo ratings yet

- NegligenceDocument2 pagesNegligenceMehreen NaushadNo ratings yet

- Law Assignment 1Document6 pagesLaw Assignment 1Inez YahyaNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort: Donoghue V Stevenson (1932)Document3 pagesLaw of Tort: Donoghue V Stevenson (1932)Sermon Md. Anwar HossainNo ratings yet

- TORT Occupier LiabilityDocument7 pagesTORT Occupier Liabilitytcs100% (1)

- Duty of Care Police Knightley V Johns & Ors (1982) 1 WLR 349 Court of AppealDocument9 pagesDuty of Care Police Knightley V Johns & Ors (1982) 1 WLR 349 Court of AppealgayathiremathibalanNo ratings yet

- Tort Revision: Introduction To Tort - I-TutorialDocument23 pagesTort Revision: Introduction To Tort - I-TutorialSam CatoNo ratings yet

- Cases Used For NegligenceDocument3 pagesCases Used For NegligenceMadeline MoeyNo ratings yet

- Breach of Duty of Care in The Tort of NegligenceDocument7 pagesBreach of Duty of Care in The Tort of Negligenceresolutions83% (6)

- Tort Tutorial 3Document8 pagesTort Tutorial 3shivam kNo ratings yet

- Occupier's Liability 2Document7 pagesOccupier's Liability 2anadiadavidNo ratings yet

- Gross Negligence ManslaughterDocument53 pagesGross Negligence Manslaughterapi-24869020180% (5)

- Negligence - DoC NotesDocument9 pagesNegligence - DoC NotesprincessdlNo ratings yet

- Involuntary ManslaughterDocument10 pagesInvoluntary ManslaughterShantel Scott-LallNo ratings yet

- Torts Exam NotesDocument9 pagesTorts Exam NotesSara Darmenia100% (2)

- 10d - Negligence Flow (Main 5)Document1 page10d - Negligence Flow (Main 5)Beren RumbleNo ratings yet

- Answer MistakeDocument2 pagesAnswer Mistakeapi-234400353100% (1)

- Canadian Torts Map and SummariesDocument19 pagesCanadian Torts Map and SummariesJoe McGradeNo ratings yet

- 4 Level 6 - Unit 13 Law of Tort Suggested Answers - June 2013Document18 pages4 Level 6 - Unit 13 Law of Tort Suggested Answers - June 2013Rossz FiúNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort 1Document8 pagesLaw of Tort 1Laurance NamukambaNo ratings yet

- Tort - Negligence - Duty of Care - Nervous ShockDocument1 pageTort - Negligence - Duty of Care - Nervous ShockMikhail Eremenko100% (1)

- Law of Tort Employers LiabilityDocument13 pagesLaw of Tort Employers LiabilitySophia AcquayeNo ratings yet

- The Liability Risk: Prof Mahesh Kumar Amity Business SchoolDocument39 pagesThe Liability Risk: Prof Mahesh Kumar Amity Business SchoolasifanisNo ratings yet

- Occupiers Liability 1Document5 pagesOccupiers Liability 1Harri Krshnnan100% (1)

- Tort of Vicarious LiabilityDocument95 pagesTort of Vicarious LiabilityFayia KortuNo ratings yet

- Law Express Question and AnswerDocument6 pagesLaw Express Question and AnswerKimberly OngNo ratings yet

- Australian Torts Law - Week 11 - Breach of Statutory DutyDocument6 pagesAustralian Torts Law - Week 11 - Breach of Statutory DutyRyan GatesNo ratings yet

- Tort of Negligence Damage and InjuryDocument12 pagesTort of Negligence Damage and Injurysada_1214No ratings yet

- Acts and OmissionsDocument5 pagesActs and OmissionsIvan LeeNo ratings yet

- Froom V Butcher CaseDocument2 pagesFroom V Butcher CaseCasey HolmesNo ratings yet

- Tort Lecture Notes AllDocument31 pagesTort Lecture Notes AllRossz FiúNo ratings yet

- Tort Report 2019 BDocument11 pagesTort Report 2019 BholoNo ratings yet

- Law203 Torts NotesDocument70 pagesLaw203 Torts NotesEllenChoulman0% (1)

- Pure Economic Loss Liability RulesDocument5 pagesPure Economic Loss Liability RulesCHONG KAI SENNo ratings yet

- Pure Economic Loss & Negligent Misstatements in United Kingdom and Malaysia 2Document24 pagesPure Economic Loss & Negligent Misstatements in United Kingdom and Malaysia 2Imran ShahNo ratings yet

- Reckless ManslaughterDocument2 pagesReckless ManslaughterMorgan FrayNo ratings yet

- The Ryland's Vs Fletcher CaseDocument15 pagesThe Ryland's Vs Fletcher CaseMario UltimateAddiction HyltonNo ratings yet

- Tort Short NotesDocument12 pagesTort Short NotesSha HazannahNo ratings yet

- Negligent MisstatementsDocument4 pagesNegligent MisstatementsKarenChoiNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 5 - RemotenessDocument8 pagesWorksheet 5 - RemotenessBrian PetersNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law: Philip RawlingsDocument81 pagesCommercial Law: Philip RawlingsthomasNo ratings yet

- Trespass To Person: Assault, Battery and False ImprisonmentDocument23 pagesTrespass To Person: Assault, Battery and False ImprisonmentMuskan Khatri100% (1)

- In Law of Torts AssignmentDocument4 pagesIn Law of Torts AssignmentRohan MohanNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort Assignment 1Document7 pagesLaw of Tort Assignment 1Eric AidooNo ratings yet

- University of Sydney Tort Question Answer SampleDocument4 pagesUniversity of Sydney Tort Question Answer SampletcsNo ratings yet

- Tort Law CaselistDocument106 pagesTort Law CaselistRox31100% (1)

- Delict Lecture Notes (Scotland)Document96 pagesDelict Lecture Notes (Scotland)ElenaNo ratings yet

- LAW2010 EmployersLiabilityDocument12 pagesLAW2010 EmployersLiabilityRondelleKeller100% (4)

- Automatism: Broome V Perkins (1987) Crim LR 271Document9 pagesAutomatism: Broome V Perkins (1987) Crim LR 271Virtue IntegrityNo ratings yet

- A V Secretary of State For The Home DepartmentDocument4 pagesA V Secretary of State For The Home DepartmentRic SaysonNo ratings yet

- Occupiers LiabilityDocument19 pagesOccupiers Liabilityuniqu0rnNo ratings yet

- NEGLIGENCE NotesDocument25 pagesNEGLIGENCE NotesMinahil Fatima0% (1)

- Negligence-TORTS NOTESDocument50 pagesNegligence-TORTS NOTESMusa MomohNo ratings yet

- Linking Bare Act: Link Life With LawDocument11 pagesLinking Bare Act: Link Life With LawSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument12 pagesVicarious LiabilitySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument12 pagesVicarious LiabilitySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument18 pagesHistorySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Volenti Non Fit InjuriaDocument10 pagesVolenti Non Fit InjuriaSaurabhDobriyal80% (5)

- Trespass To LandDocument5 pagesTrespass To Landparijat_96427211No ratings yet

- Strict & Absolute LiabilityDocument6 pagesStrict & Absolute LiabilitySaurabhDobriyal100% (4)

- NegligenceDocument8 pagesNegligenceSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Strict & Absolute LiabilityDocument6 pagesStrict & Absolute LiabilitySaurabhDobriyal100% (4)

- Statutory AuthorityDocument1 pageStatutory AuthoritySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Res Ipsa LoquiturDocument6 pagesRes Ipsa LoquiturSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- in The Leading Case Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee ( (1957) 2 AllDocument5 pagesin The Leading Case Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee ( (1957) 2 AllSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Standard of CareDocument11 pagesStandard of CareSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- in The Leading Case Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee ( (1957) 2 AllDocument5 pagesin The Leading Case Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee ( (1957) 2 AllSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Malicious ProsecutionDocument6 pagesMalicious ProsecutionSaurabhDobriyal67% (3)

- Consumer & Deficiency in ServiceDocument7 pagesConsumer & Deficiency in ServiceSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Vicarious LiabilityDocument4 pagesDoctrine of Vicarious LiabilitySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- DefamationDocument7 pagesDefamationSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Inevitable AccidentDocument8 pagesInevitable AccidentSaurabhDobriyal100% (4)

- DefamationDocument7 pagesDefamationSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Vicarious LiabilityDocument4 pagesDoctrine of Vicarious LiabilitySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Consumer & Deficiency in ServiceDocument7 pagesConsumer & Deficiency in ServiceSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- BasicsDocument11 pagesBasicsSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Caveat Emptor & Caveat VenditorDocument6 pagesCaveat Emptor & Caveat VenditorSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Caveat Emptor & Caveat VenditorDocument6 pagesCaveat Emptor & Caveat VenditorSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Breach of Duty - Reasonable ManDocument6 pagesBreach of Duty - Reasonable ManSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Economic and Financial Developments in UttarakhandDocument15 pagesEconomic and Financial Developments in UttarakhandAshwinkumar PoojaryNo ratings yet

- Act of GodDocument7 pagesAct of GodSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- OBLICON Contracts FinalsDocument10 pagesOBLICON Contracts FinalsPaulo LunaNo ratings yet

- Parker v. Highland Park, Inc., 565 S.W.2d 512 (Tex., 1978)Document10 pagesParker v. Highland Park, Inc., 565 S.W.2d 512 (Tex., 1978)BrandonNo ratings yet

- Torts DoctrinesDocument56 pagesTorts DoctrinesElwell MarianoNo ratings yet

- Legal Research Trail - JavaDocument14 pagesLegal Research Trail - JavaClement LingNo ratings yet

- 8 Insurance LawDocument25 pages8 Insurance LawUtpal RoyNo ratings yet

- Torts, Negligence and Product Liability Chapter 7 (2ed)Document32 pagesTorts, Negligence and Product Liability Chapter 7 (2ed)api-522706100% (5)

- Digest Nolasco v. Cuerpo GR No. 219215Document3 pagesDigest Nolasco v. Cuerpo GR No. 219215Rav EnNo ratings yet

- Ali Akang Vs - Municipality of Isulan, Sultan Kudarat ProvinceDocument3 pagesAli Akang Vs - Municipality of Isulan, Sultan Kudarat Provincemiles1280No ratings yet

- Performance Breach and Frustration TutorialDocument9 pagesPerformance Breach and Frustration TutorialAdam 'Fez' FerrisNo ratings yet

- Law of Contract Zzds (Part I)Document27 pagesLaw of Contract Zzds (Part I)Yi JieNo ratings yet

- NotepadDocument24 pagesNotepadheberdonNo ratings yet

- Natural LawDocument3 pagesNatural LawKDNo ratings yet

- General Defences (Module 4)Document26 pagesGeneral Defences (Module 4)Sharath Kanzal0% (1)

- Article 1159Document2 pagesArticle 1159Eliza Jayne Princess VizcondeNo ratings yet

- Discharge of ContractDocument11 pagesDischarge of ContractJacob Toms NalleparampilNo ratings yet

- NegligenceDocument6 pagesNegligenceMadhav MitrukaNo ratings yet

- Rectification or Cancellation of InstrumentsDocument13 pagesRectification or Cancellation of InstrumentsVarun OberoiNo ratings yet

- Question 1: Was There An Agreement For Promise?Document19 pagesQuestion 1: Was There An Agreement For Promise?alivanhornNo ratings yet

- Answering Problem Questions (Law)Document2 pagesAnswering Problem Questions (Law)fggggg23100% (2)

- Summary For Contracts PDFDocument16 pagesSummary For Contracts PDFLeslie An GarciaNo ratings yet

- 'Entire Agreement' Clauses - How EffectiveDocument11 pages'Entire Agreement' Clauses - How EffectiveWilliam TongNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Ashrul Haikal Bin Ashri 255762 Law of Equity and Trust I Tutorial 2Document2 pagesMuhammad Ashrul Haikal Bin Ashri 255762 Law of Equity and Trust I Tutorial 2Ash HykalNo ratings yet

- Law On Obligations and ContractDocument24 pagesLaw On Obligations and ContractAJSINo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Essentials of Business Law 10th Edition Anthony Liuzzo Ruth Calhoun Hughes Full DownloadDocument11 pagesSolution Manual For Essentials of Business Law 10th Edition Anthony Liuzzo Ruth Calhoun Hughes Full Downloadtracyherrerabqgyjwormf100% (34)

- Failure To Object: ARTICLE 1405Document4 pagesFailure To Object: ARTICLE 1405Joshua DaarolNo ratings yet

- Obligation and Contracts-ECEDocument45 pagesObligation and Contracts-ECECrisJoshDizon50% (6)

- 230 Philippine Legal DoctrinesDocument19 pages230 Philippine Legal DoctrinesChabby Chabby100% (1)

- Business Law NotesDocument116 pagesBusiness Law NotesTyler SmallwoodNo ratings yet

- Contract 1 Repeat Sem 1 PDFDocument20 pagesContract 1 Repeat Sem 1 PDFMuskan KhatriNo ratings yet

- Obligations and ContractsDocument42 pagesObligations and ContractsMARYLIZA SAEZNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Wall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementFrom EverandWall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- Buffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorFrom EverandBuffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- How to Win a Merchant Dispute or Fraudulent Chargeback CaseFrom EverandHow to Win a Merchant Dispute or Fraudulent Chargeback CaseNo ratings yet

- Getting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorFrom EverandGetting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- IFRS 9 and CECL Credit Risk Modelling and Validation: A Practical Guide with Examples Worked in R and SASFrom EverandIFRS 9 and CECL Credit Risk Modelling and Validation: A Practical Guide with Examples Worked in R and SASRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- AI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersFrom EverandAI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersNo ratings yet

- Disloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpFrom EverandDisloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (214)

- The SHRM Essential Guide to Employment Law, Second Edition: A Handbook for HR Professionals, Managers, Businesses, and OrganizationsFrom EverandThe SHRM Essential Guide to Employment Law, Second Edition: A Handbook for HR Professionals, Managers, Businesses, and OrganizationsNo ratings yet

- The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesFrom EverandThe Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- LLC: LLC Quick start guide - A beginner's guide to Limited liability companies, and starting a businessFrom EverandLLC: LLC Quick start guide - A beginner's guide to Limited liability companies, and starting a businessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Learn the Essentials of Business Law in 15 DaysFrom EverandLearn the Essentials of Business Law in 15 DaysRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Competition and Antitrust Law: A Very Short IntroductionFrom EverandCompetition and Antitrust Law: A Very Short IntroductionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Building Your Empire: Achieve Financial Freedom with Passive IncomeFrom EverandBuilding Your Empire: Achieve Financial Freedom with Passive IncomeNo ratings yet

- Indian Polity with Indian Constitution & Parliamentary AffairsFrom EverandIndian Polity with Indian Constitution & Parliamentary AffairsNo ratings yet

- Economics and the Law: From Posner to Postmodernism and Beyond - Second EditionFrom EverandEconomics and the Law: From Posner to Postmodernism and Beyond - Second EditionRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The Real Estate Investing Diet: Harnessing Health Strategies to Build Wealth in Ninety DaysFrom EverandThe Real Estate Investing Diet: Harnessing Health Strategies to Build Wealth in Ninety DaysNo ratings yet

- How to Structure Your Business for Success: Choosing the Correct Legal Structure for Your BusinessFrom EverandHow to Structure Your Business for Success: Choosing the Correct Legal Structure for Your BusinessNo ratings yet