Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011: Thailand Thailand

Uploaded by

Ikhsan AmadeaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011: Thailand Thailand

Uploaded by

Ikhsan AmadeaCopyright:

Available Formats

WHO Country Coopcration Stratcgy

2008-2011

Permanent 8ecretary u||d|ng No.3

4th f|oor, H|n|stry of Pub||c hea|th

T|wanon Road, Huang

Nonthabur| 11000

Tha||and

www.whotha|.org

Thailand

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy

2008-2011

, July

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 ii

World Health Organization 2007

Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance

with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. For rights of

reproduction or translation, in part or in toto, of publications issued by the WHO Regional

Office for South-East Asia, application should be made to the Regional Office for South-

East Asia, World Health House, Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi 110002, India.

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not

imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the

World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or

area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Thailand iii

Contents

Preface .............................................................................................................. v

Foreword ........................................................................................................ vii

Executive Summary .......................................................................................... ix

1. Introduction ............................................................................................... 1

2. Country health and development challenges in Thailand ............................ 3

1. Economic and social development ................................................................. 3

2. Health policies ............................................................................................... 4

3. Burden of disease and the health development situation ................................ 5

3. Development assistance and partnerships:

Aid flow, instruments and coordination..................................................... 17

1. Partnership with UN and other international development agencies ............. 17

2. Partnership with developing countries .......................................................... 19

3. Technical cooperation with other countries .................................................. 19

4. WHO Collaborating Network....................................................................... 20

4. Current WHO cooperation....................................................................... 21

1. Work of the WHO Country Office encompasses .......................................... 21

2. Focus of WHOs collaboration with Thailand ............................................... 21

3. Funding of WHO collaborative programmes. ............................................... 22

4. Fellowships .................................................................................................. 22

5. Regional Sub-units ....................................................................................... 23

6. Staffing ........................................................................................................ 23

7. Office premises ............................................................................................ 24

8. Information and communication technology ................................................ 24

9. Use of CCS .................................................................................................. 24

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 iv

5. WHO policy framework Global and regional directions ......................... 25

1. Global challenges in health .......................................................................... 25

2. Global health agenda ................................................................................... 26

3. Regional policy framework ........................................................................... 27

6. Strategic agenda: Priorities jointly agreed for WHO cooperation

in and with countries ................................................................................ 28

1. Principles ..................................................................................................... 28

2. Strategic agenda .......................................................................................... 28

3. Modalities of implementation: ..................................................................... 32

7. Implementing the strategic agenda: Implication for

WHO Secretariat, follow-up and next step at each level ........................... 34

1. Introduction................................................................................................. 34

2. Staffing: Current and future.......................................................................... 34

3. Financial allocation ...................................................................................... 35

4. Information and communication support ..................................................... 35

5. Implementation of the strategic agenda ........................................................ 35

Annexes

1. National health development data ............................................................... 37

2. Strategic objectives and their scope under MTSP 2008-2013 ....................... 38

3. MoPH budget in present value and real terms .............................................. 43

4. Health budget allocation for major types of programmes during

the first half of the Ninth National Health Development Plan ....................... 44

5. Thailands scorecard on MDG Targets (Goal 1-7) .......................................... 45

6. Organogram Ministry of Public Health....................................................... 46

7. Morbidity rates of hospitalized cases (per 100 000 population)

due to selected NCDs, injuries and mental illness Thailand

(excluding Bangkok), 20012004 ................................................................. 47

8. Organogram WHO Country Office Thailand ................................................ 48

9. References ................................................................................................... 49

Thailand v

Collaborative activities of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the South-East

Asia (SEA) Region are geared to improve the health status of the population of Member

States. Although WHO has been contributing as a key catalyst to Thailands health

policies and programmes, there is a need to thoroughly analyze and discuss how the

Organization can further improve its contribution to the development of health in

Thailand.

The South-East Asia Region was the first among WHOs Regions to promote the

Country Cooperation Strategy (CCS) as a process to identify how the Organization can

best support health development in our Member States. All 11 Member States of the

Region have prepared their CCSs over the past six years. In the case of Thailand, two

CCSs have already been prepared and have been used continuously as guidelines for

the WHO Country Office (WCO) to plan and coordinate work effectively with their

national as well as international counterparts for health development in the country.

Analyses of the current health situation and the likely scenario over the next four

years have together formed the basis of the priorities outlined in this CCS. The inputs

and suggestions from the Ministry of Public Health, whose officials have been the

major collaborators in developing this document, are appreciated. In addition, the

advice and recommendations of the health development partners in Thailand and the

United Nations Partnership Framework (UNPAF) 2007-2011, of which the WHO

Country Office is also a signatory, were invaluable in guiding the development of this

CCS. The consultative process here will help ensure that WHO inputs provide the

maximum support to health development efforts in the country.

To help achieve the objectives of this CCS and to promote technical assistance

from Thailand to other Member countries, we recognize the importance of a strong

WHO Country Office working closely with key counterparts, keeping in mind local

conditions. Nonetheless, the entire organization is committed to the work of the CCS.

The staff of the WHO Regional Office will use this CCS to determine regional priorities

and support collaborative activities in Thailand. Furthermore, we will also seek assistance,

as necessary, from WHO Headquarters towards bolstering these efforts.

I would like to thank the Ministry of Public Health and Faculty of Tropical Medicine,

Mahidol University, Bangkok for providing office space for the regional-level units,

Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response Sub-unit and the Malaria Mekong

Sub-unit.

Preface

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 vi

I would like also to specially thank all those who have contributed to development

of this Country Cooperation Strategy, which has the full commitment of the Regional

Office. We will provide our maximum support towards achieving its objectives over

the next four years. Our joint efforts, I am confident, will help in achieving the maximum

health benefits for the people of Thailand.

Samlee Plianbangchang, M.D., Dr.P.H.

Regional Director

Thailand vii

Thailand is one of the countries in the South-East Asia Region that have an advanced

health infrastructure, a robust surveillance system and public health professionals with

a high degree of expertise. The country has demonstrated excellence and expertise in

many areas of public health, medical specialities and nursing. Thailand has also achieved

many of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

The WHO Country Office (WCO) is in a unique position to have national experts

in both long-term and short-term positions who can contribute to the work of the

Organization in Thailand. The Country Office also facilitates training programmes for

Fellows from neighbouring countries and other Member countries of the Region, for

capacity building.

Even with such remarkable progress, communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS,

tuberculosis (TB) and avian influenza (AI) continue to have a negative impact on the

country, with certain situations exacerbated by the prevalent circumstances along

Thailands borders. Health promotion efforts and control measures for NCDs are well

advanced in terms of both legislation and intervention. The WCO provides the necessary

support to enhance these efforts.

The purpose of this Country Cooperation Strategy (CCS) is to reflect the medium-

term vision of WHO for its cooperation with Thailand and to elucidate the strategic

framework for such cooperation. The CCS represents a balance between evidence-

based country priorities and organization-wide strategic priorities in order to contribute

optimally to national health development.

It is very timely for WCO Thailand to prepare the new CCS covering the period

2008-2011, since the current Strategy will end in 2007. The WHO Medium-Term

Strategic Plan (MTSP) 2008-2013 is being prepared and a new planning approach has

been introduced. The priorities and strategic framework are based on: (1) National

and international partners recommendations; (2) The national health development

situation, and (3) Strategic objectives of WHO and the Regional Office for South-East

Asia under the MTSP. Overall, the priorities and strategic framework presented in this

CCS are consistent with WHOs strategic objectives in meeting Thailands needs.

We hope that this CCS shall be disseminated and used by national and international

partners in health for better cooperation and collaboration in planning and implementing

relevant activities to enhance the health and well-being of the people of Thailand.

P.T. Jayawickramarajah, M.D., M.Ed., Ph.D

WHO Representative to Thailand

Foreword

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 viii

Thailand ix

Executive Summary

Since the current Country Cooperation Strategy (CCS) will end in 2007, the preparation

of a new CCS is timely to cover the period of 2008-2011. In the context of a new CCS,

it is relevant to list the following important related documents that are being or have

been prepared for the corresponding period: (a) The 10

th

National Health Development

Plan, 2007-2011; (b) The WHO six-year Medium Term Strategic Plan (MTSP), 2008-

2013, which serves as an outline of WHOs strategic objectives and (c) The United

Nations Partnership Framework, Thailand (UNPAF 2007-2011), of which the WHO

Country Office is also a signatory.

Thailand is a developing country that has registered impressive successes in both

economic and social development, though all regions of the country have not registered

the same degree of advancement. The country also has a long and successful history of

health development. The Ninth Five-Year National Health Development Plan, 2001-

2006, has just been completed, and the Tenth Plan is in the final stages of completion.

The basic principles of these plans are based on a people-centered approach and

philosophy of sufficiency economy. The Thailand Human Development Index has

improved, inexorably aided by major contributions from the robust health indicators.

Almost all MDGs relating to maternal and child mortality have been achieved.

Although considerable progress and achievement has been registered, Thailand

still faces several challenges with the health situation and health development. Some

of the major challenges to advancement of health development are as follows:

(1) Important communicable diseases remain key public health concerns in

Thailand. These include malaria, dengue haemorrhagic fever, HIV/AIDS, TB

and emerging diseases, particularly avian influenza. The coordination of the

disease surveillance and epidemic response, and the efficiency of DOTS at

the peripheral level still leave room for improvement.

(2) Morbidity and mortality of major non-communicable diseases such as injuries

and mental illnesses show a rising trend. The country requires clear and

well-defined national multi-sectoral coordination policies and strategies for

the effective prevention and control of these diseases.

(3) Environmental pollution and contamination of food by hazardous substances

are still important public health issues. Occupational safety standards and

the permissible levels of hazardous substances are yet to be enumerated.

(4) Thailand has increasingly become prone to natural disasters. Although the

government is relatively self-reliant in disaster relief, WHO and the UN Disaster

Management Team have important roles to play to support the country in

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 x

assessing the health situation and needs as well as coordinating joint action

for health.

(5) Cross-border health risks have become important health and political issues

over the past few years. These risks include the spread of communicable

diseases and drug-resistant pathogens, and also national security. There are

many players involved in the improvement of the living conditions and health

of migrants and refugees along the border of Thailand. Better coordination

among all involved is needed.

(6) Thailand has accorded high priority to health promotion, as is clearly reflected

in the Ninth and Tenth National Health Development Plans. The Ministry of

Public Health (MoPH) has initiated many programme and project approaches.

The Thailand Health Promotion Foundation plays an important role in

financing and advocating health promotion. However, the countrys main

challenge lies in establishing firm levels of collaboration with sectors outside

of the Ministry of Public Health.

(7) The most recent phase of health systems reform began in 2000. Several offices

and institutes were established to strengthen health systems development

and enable the reform process. For example, the National Health Systems

Research Institute (HSRI) established the Health Systems Reform Office to

function as the secretariat for the National Health Systems Reform Committee

to guide health systems development. The International Health Policy

Programme (IHPP) was established to develop and strengthen national

capacity in health policy research and international health. The National

Health Security Office (NHSO) was established in 2003 to expand coverage

of health insurance/security for those citizens who have not as yet been

covered by any government insurance scheme.

The national health budget has gradually increased from 5.8% of the total

government outlay in 1993 to 7.6% in 2004. About 60% of all health expenditure

comes from government sources compared with 40% from private sources. In 2001

the government introduced the Universal Health Care (UC) policy (the 30-Baht

scheme). In April the next year, the government announced universal health care

coverage and in 2007 universal coverage without pay was introduced. In 2004, the

UC scheme represented 75.2% of the total health insurance schemes that covered a

population of about 47 million. There are still issues concerning the quality of services,

sustainability of the schemes, and the resignation of physicians from public service that

need to be addressed.

Thailand is gradually becoming a development partner, like other middle-income

countries, by assisting other developing countries. Therefore, in terms of developmental

assistance, Thailand has received mostly technical support, but only limited financial

support, from donor agencies and countries. In relation to partnerships with developing

Thailand xi

countries, Thailand is active in a number of regional and sub-regional cooperative

initiatives in many sectors including health.

The work of WHO with Thailand is based on the WHO-Country Collaborative

Programme, which is developed on a biennial basis. The WCO focuses overall on

supporting policy development, advocacy, technical advice, and the development of

norms, standards and guidelines. In addition to the WCO, there are two WHO sub-

regional units in Thailand: a) Mekong Malaria Control Project (MMP) that was established

for coordinating malaria control activities in the countries of the Mekong Basin that

involves two WHO Regions and for coordinating border health activities, and b)

Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response (CSR) regional sub-unit that was

established to support countries to strengthen capacities in areas of epidemiology,

disease surveillance and epidemic response. The WCO has National Professional

Officers (NPO) who work in programme planning, monitoring and evaluation, HIV/

AIDS-Tuberculosis, communicable disease control and tobacco control. All other

international technical staff are assigned to work for the above two sub-units.

WHO has established a clear Global and Regional Framework, under the Tenth

General Programme of Work (GPW) and the Medium Term Strategic Plan (MTSP), and

all the offices will work to perform six core functions of WHO.

Based on the above situation analysis and extensive consultations, the following

seven strategic agendas have been identified as priorities for the next four years:

(1) To enhance primary prevention, surveillance and control of communicable

diseases and epidemics;

(2) To integrate measures to reduce the risks of non-communicable diseases

(NCDs), injuries and mental illnesses;

(3) To build capacity and partnerships for health promotion and healthy public

policy;

(4) To strengthen capacity for monitoring and evaluating health systems

development;

(5) To initiate a multi-sectoral approach to address health services for the poor

and at-risk population, including those in border and conflict areas;

(6) To promote environmental health and surveillance of environmental hazards;

(7) To strengthen the development of human resources for health through existing

networks within and outside the country.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 viii

Thailand 1

Thailand is one of the countries that has already formulated two Country Cooperation

Strategy (CCS)* reports. The first covered the period of 20022005, and it was later

updated in 2004 for 20042007. As one of the fundamental principles of the CCS, the

strategic agendas identified in these documents have been used as a basis for the

WHO country collaborative programmes and for the Organizations operations in the

country.

The CCSs were developed in close consultation with the national authorities from

within and outside the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH). Consultations were held

with most UN Agencies and other partners who are active in the health sector. As the

current CCS will end in 2007, it is timely to formulate a new CCS for the following

reasons:

(1) The Royal Thai Government (RTG) has drafted its Tenth National Health

Development Plan (20072011) which outlines its strategies and priorities

based on the vision of sufficiency economy. This will allow WHO to align

its medium-term strategies, including the planning cycle, with the strategies

and priorities of the RTG.

(2) The six-year WHO Medium-Term Strategic Plan (MTSP) based on WHOs

Eleventh General Programme of Work (GPW) 20062015 outlines the

Organizations global strategies covering the period 20082013. This exercise

can take into account the latest WHO long- and medium-term strategies

and priorities while identifying the Organizations strategic agenda for its

technical cooperation with the RTG for the period 20082011. This will also

help RTG respond, in a flexible and dynamic manner, to a changing

international health environment.

(3) The United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF), which is

referred to in Thailand as the United Nations Partnership Framework (UNPAF),

covering the period 20072011, has just been developed and fully aligned

Introduction

1

*The CCS reflects a medium-term vision of WHO for its work with a given country and defines a strategic agenda

for working with that country. The timeframe is four to six years but may be less for countries in crisis. The CCS

is the WHO instrument used to aligning with the national agenda while harmonizing with the functions of other

organizations in the UN system and other agencies in the country.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 2

with the national priorities. WHO, as agreed in the Paris Declaration, follows

the principles for alignment and harmonization of its strategies and

programmes with that of the United Nations system and other development

partners working in the area of health. Although the WHO Country Office,

Thailand did not have a distinctive role to play in the poverty reduction

strategy of UNDAF, the strategy was considered a core value and an

overlapping element that has to be integrated into WHOs strategic objectives.

Taking advantage of the opportunities stated above and in accordance with the

agreements with the national authorities, it was decided to formulate the CCS in Thailand

for WHOs cooperation with RTG over the period of 2008-2011.

Thailand 3

1. Economic and social development

In terms of social and economic development, Thailand has achieved outstanding

progress over the last few decades to emerge a middle-income country. Per capita

income in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in 2005 was (Intl. $) 8440. Thailand

has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.784, which increased from 0.615 in

1975. The number of people living below the poverty line was reduced by almost two-

thirds between 1990 and 2002. The reach of education has also increased, with almost

all children attending primary school and enrolment in secondary schools rising every

year. Aided by high levels of attendance in schools, the literary rate is currently 92.6%

1

.

Despite this impressive progress, the fruits of development have not reached all

regions of the country in equal measure. While the Bangkok Metropolitan Area in

2002 had less than 2% of its population living in poverty, the incidence of poverty was

as high as 16% in the north, 17% in the north-east, and 8% in the south of the country.

Poverty rates in Narathiwat and Pattani, two of the southern-most provinces, were

18% and 23%, respectively

2

. Furthermore, drawn by Thailands economic wealth and

stability in comparison with some of its neighbours, many migrants arrived in search of

employment and a living. These migrants do not always have full access to social

services such as health care and those not registered are often vulnerable to exploitation.

The Tenth National Health Development Plan, currently in draft form, covering

the period 20072011 will follow the vision and philosophy of the Ninth Plan. This

new plan focuses on three areas for strengthening and developing the national capital

formation: (a) economic capital, (b) social capital, and (c) natural resources and the

environment. Health falls under social capital, and the health sector is considered to

be a new wave in Thailands competitive surge in the context of global trade

liberalization. While the Ninth Plan has emphasized a life-cycle health approach,

promoting healthy lifestyles, improving the quality of health care, disease prevention

and control, and preparing for the need of an ageing population, the Tenth Plan

emphasizes public and national self-reliance in health.

In the past, government administration and services had been largely centralized.

However, decentralization is now an accepted political objective and is gradually being

implemented. Efforts are already on to decentralize public services, including health,

to the 76 provinces and 876 districts, including Bangkok. This will require substantial

efforts to build capacity at the local level.

Country health and development

challenges

2

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 4

2. Health policies

Thailand has had a long history of health development going back to the 13

th

Century.

More recently, the First (five-year) National Health Development Plan was initiated in

1961, and subsequent plans continued through the Ninth Plan, which covered the

period 20012006. There has been continuous change in and evolution of health

policies in response to the countrys social and health problems and in line with

international developments in health. At the end of the Seventh Plan and throughout

the Eighth Plan, WHO introduced a Health Future Studies approach to the Ministry of

Public Health. Consequently, since 1999 public sector reform, including health, has

been part of the governments agenda.

The Ninth Plan provided a clear vision of a people-centered approach and the

philosophy of a sufficiency economy. Its objectives were to: (a) promote health and

prevent and control diseases; (b) establish health security; (c) build capacity in health

promotion and health system management; and (d) establish measures in generating

knowledge through research. In 2003 Healthy Thailand was adopted as a national

agenda to be used as guidance to reducing behavioural risks and to solve major health

problems in pursuing the target Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015.

While continuing with the philosophy of sufficiency economy, the Tenth National

Health Development Plan places more emphasis on national self-reliance, quality of

services, peoples values and dignity. Its objectives are as follows:

Develop uniformity and good governance in the management of health

systems.

Accelerate the pro-active health promotion approach to develop basic

elements for good health.

Develop a health culture and ways of life with sufficiency and happiness.

Develop community health systems and a strong primary care service network.

Develop a health service system that will lead to both health care receivers

and health care providers satisfaction.

Develop health security systems with equitability, good quality, and better

distribution.

Develop individuals immune systems and readiness to minimize the impact

from diseases and risks to health.

Develop several alternative healthcare services, integrating the respective

strengths of Thai and international approaches.

Develop a foundation of health knowledge through knowledge management.

Develop societies that do not neglect sufferers and that care for the poor and

disadvantaged people with due respect for their values and human dignity.

Thailand 5

In September 2006, political developments led to the establishment of an interim

government in Thailand. The health minister subsequently announced health policies

that are in line with the Tenth National Health Development Plan. On account of the

problems that were encountered in implementing the 30-Baht health-care scheme,

universal coverage without fees was initiated. In general, health systems reform and

health security, especially social health insurance, will continue to be an important

part of the health development agenda in Thailand for the next four to five years.

3. Burden of disease and the health development situation

Along with Thailands impressive economic development, the government has

developed an effective public health system to improve the health of its population.

Since 1989, Thailands Infant Mortality Ratio (IMR) has improved from 38 per 1000

live births in 1990 to 19.8 in 2005

3

. According to the Millennium Development Goals

Report 2004, the maternal mortality rate, a good indicator of the effectiveness of a

public health system, has decreased from 36.2 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 14 in

2002, with about 98% of births having been attended by skilled health personnel.

Thailands progress with the MDGs (Annex 5) has been so impressive that the country

has adopted targets beyond those in the MDGs, which are known as the MDG-Plus

targets. However, despite the progress made with the MDGs, challenges still remain in

those regions with a high number living in poverty and among migrant populations,

particularly in the border areas.

Thailand is witnessing a series of both demographic and epidemiologic transitions.

The total fertility rate (TFR) has dropped from 2.41 in 1990 to 1.6 in 2006 with an

average population growth rate of 0.7% in 2004-15

2

. With the reduction in

communicable diseases, improved nutritional status, and the provision for skilled birth

care, the pattern of morbidity and mortality has gradually veered towards non-

communicable Diseases (NCDs), injuries and mental illness.

3.1 Communicable diseases

While progress has been made in the reduction of communicable diseases, some

significant problems remain. These will be the focus of efforts during the next four

years, as enumerated below:

(a) HIV/AIDS: In 1991, the number of new HIV infections reached 143,000,

indicating that Thailand was on the brink of a major health crisis. The

Government, working with NGOs, mobilized effective interventions to

increase general awareness on HIV and thereby reduced the transmission of

HIV appreciably. With the number of new infections at 19,000 per annum

in 2004, Thailand is one of the few countries to make substantial progress in

fighting AIDS. Currently, of the estimated 500,000 people who are living

with AIDS, anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) are being provided to about 100,000

of them who urgently need such treatment. With the government committal

since October 2003 to the policy of universal access to anti-retroviral drugs

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 6

for AIDS patients. But with the possibility of limited funds for the same, the

authorities, in March 2007 applied compulsory licensing measures to produce

two low-price, generic HIV/AIDS drugs. Over the past three years there has

been growing concern regarding the increasing incidence of HIV/AIDS among

adolescents, almost consistent with an increasing incidence of sexually

transmitted infections (STIs).

(b) Tuberculosis: Thailand ranks 17

th

of the 22 global high-burden countries for

tuberculosis

4

. The DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment, Strategy) still requires

strengthening to ensure higher case detection and treatment success rates.

In 2004, the country achieved the 70% case detection target. However, the

treatment success rate achieved was 74% which is significantly lower than

the target of 85%. There is a need to strengthen TB programme management

and capacity to guide and oversee the implementation of TB services under

the decentralized health system. The lack of coordination between various

stakeholders including provincial administrations poses constraints to the

programme. Inadequate treatment supervision and sub-optimal drug

procurement and supply management need to be addressed. The emergence

of multi-drug resistance and a high HIV prevalence among TB patients, the issue of

TB among migrants both internal and in the border areas, are other major concerns.

The WHO estimates for tuberculosis incidence and mortality rates in Thailand

in 2005 were 142 and 19 per 100,000 population

4

respectively. These rates

are about three and 80-fold higher respectively than those reported under

the routine surveillance system, Bureau of Epidemiology

5

. However, the

surveillance report has been used for monitoring the disease trends rather

than the actual disease burden (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Morbidity and mortality of pulmonary turberculosis, Thailand, 1996-2005

Source: Bureau of Epidemiology (Surveillance Data)

Thailand 7

(c) Vector-borne diseases: The countrywide incidence of malaria has been

decreasing but problems remain in border areas, both in terms of number of

cases and drug resistance. To ensure that the disease will be controlled

completely, malaria is likely to remain a vertical programme before full

integration into the routine health services. While the country has been

successful in case management of dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) and in

reducing its case fatality rate to less than 1%, disease morbidity is still high

with an increasing incidence among adults. The main strategies of disease

control have been focused on eliminating vector breeding places by

schoolchildren and on improving the environment using a healthy setting

approach. Long-term results are yet to happen. It should be noted that malaria,

DHF and outbreaks of some other communicable diseases often increase

after natural disasters.

(d) Epidemic preparedness and response: In 2003 there were nine reported cases

of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and two deaths due to it in

Thailand. Following reports of human avian influenza (AI) in China and

Vietnam in 2003, Thailand reported confirmed AI outbreaks and deaths in

poultry in July 2004. The first confirmed human case of AI in Thailand occurred

in August 2004 and by the end of November 2006 25 AI cases and 17

deaths in humans were reported. In response to this, the Government

established a multi-sectoral National Committee for Avian Influenza Control,

comprising representatives from the ministries of Public Health, Agriculture,

Natural Resources and Environment, the Institute of Animal Health, the

Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and WHO. However, it is still a

challenge to extend this coordination to the sub-national level because there

is no standard policy and decentralization is still in a transitional phase.

(e) Surveillance: Outbreaks of communicable diseases can be prevented if cases

are detected early as well as the related risk factors and effective action

immediately taken. The performance and quality of disease surveillance in

the provincial health offices and public health laboratory services in provincial

hospitals are not adequate yet. This may adversely affect the timeliness and

effectiveness of responses to epidemics. Health personnel also have to be

trained in risk communication so that families and communities will know

how to avoid high-risk behaviour related to the outbreaks or epidemics.

Efforts to strengthen surveillance systems are also needed to support the

implementation of the new and revised International Health Regulations (IHR)

2005 being implemented since June 2007. The disease surveillance system

and capacity building for epidemiology are the responsibility of the Bureau

of Epidemiology, which has since long been recognized globally as one of a

few successful centres for FETP (Field Epidemiology Training Programme).

The short-course FETP may be considered in tandem with the existing two-

year course to address the increased requirements.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 8

3.2 Maternal, child and adolescent health

While Thailand has already achieved MDG targets for child and maternal mortality on

U5MR and MMR (Annex 5), Maternal and Child Health (MCH) and reproductive

health services still need strengthening for poor households and in underserved regions.

Micronutrient deficiencies, especially of iron and iodine, remain and are often associated

with increased morbidity and retarded mental growth. Special attention is required for

adolescent health since this group is susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases such

as HIV. There are separate programmes for MCH, reproductive health and adolescent

health, while target populations are the same or overlap. School health programmes

also need strengthening to support better health practices and health services need to

be adjusted to provide effective services to adolescents.

3.3 Noncommunicable diseases, injuries, and mental health

The burden of disease in Thailand is gradually shifting to noncommunicable diseases,

injuries and mental health. The greatest public health benefits are gained through

prevention of NCD (cardiovascular diseases, cancers and diabetes mellitus in particular),

injuries and mental health disorders. This can be achieved if the risk factors are identified

and appropriate interventions implemented to reduce or avoid these risk factors. In

addition, if NCDs and mental illnesses are detected at an early stage and appropriate

controls initiated, the severity of these can be reduced. It should be noted here that

the burden of noncommunicable diseases usually falls disproportionately on the poor

who often have excess exposure to risk factors and limited access to health services.

Diseases such as diabetes, cancers and of the heart are often not detected till at an

advanced level.

Aware of the increasing trends of NCDs and injuries, the RTG has placed high

priority on prevention and control initiatives. The Bureau of Noncommunicable Diseases

is responsible for NCDs, injury prevention, and tobacco and alcohol control

programmes. The Bureau has made appreciable progress in monitoring the burden of

NCDs and injuries and identifying major behavioural risk factors classified by their

provinces. The Bureau also plans to improve the collection and analysis of NCD and

injury mortality and morbidity data in order to monitor trends and evaluate the success

of interventions for risk factors. Due to the unreliability of incidence data for selected

NCDs, injuries and mental illnesses among the population, cases of hospitalization

with more accurate diagnosis are presented to ascertain the trends in the burden of

disease depicted in Figure 2 and in Annex 7.

Since the NCD and injury prevention and control programmes emphasize the

public health and primary care approaches (rather than secondary and tertiary

treatment), effective multi-sectoral collaboration is required. Clearly, traffic injury

prevention and tobacco and alcohol control programmes cannot be implemented by

the health sector alone. The RTG has demonstrated a strong commitment to the control

Thailand 9

of tobacco use and alcohol consumption by drafting legislations, particularly in the

area of advertisement. However, the major challenge ahead remains how to effectively

reduce risk behaviour (smoking and alcohol consumption) and increase regular exercise

and healthy diet.

The Department of Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), is in the

process of developing National Strategies on Mental Health, based on the Tenth National

Health Development Plan. To ensure the success of implementation, advocacy and

multi-sectoral collaboration are required to address the root of social problems that

are considered to be the major causes of mental illness.

3.4 Environmental health and food safety

After several reorganizations in the government, the main responsibilities for water

supply and sanitation and pollution control services have been transferred from the

Ministry of Public Health to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. The

Bureau of Environmental Health limits its responsibilities to providing technical support

and capacity building, especially to local organizations. The healthy settings approach

is used to promote healthy cities with clean public toilets and healthy markets, schools

and hospitals. The Bureau is currently developing a National Environmental Health

Action Plan (NEHAP). The Health Impact Assessment (HIA) is an important tool to

minimize the adverse environmental influences on health. More support is needed to

improve national capacity for conducting HIAs. Future environmental challenges include

climate change, increasing urbanization, and the danger posed by hazardous waste

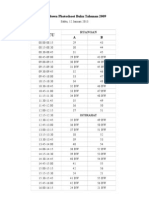

Figure 2: Morbidity rates of selected diseases/conditions in Thailand

(excluding Bangkok) 2001-2004

Source: Bureau of Policy and Strategy

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 10

and chemicals, including exposure to heavy metals in the environment. These

contaminants, from industrial or natural sources, include asbestos, cadmium, arsenic

and lead. Standards have yet to be set for permissible levels of hazardous chemicals in

food, water and the environment, and surveillance of violations should be strictly

enforced.

Although occupational health has been a prime concern for Thailand for more

than 30 years, accidents and diseases caused by the workplace environment are on

the rise. Besides accidents, the most common reports of occupational health incidents

are pesticide poisoning, skin disease due to exposure to chemicals, back pain, lead

poisoning and silicosis. The government response to these problems is rather passive,

and largely confined to providing medical care or financial compensation to the victims.

Effective prevention of occupational hazards is still limited. Systems to report all

occupational health events need to be established and strengthened. Occupational

safety standards should be established and inspections undertaken to ensure compliance.

The promotion of food safety is one of the governments priorities under the

Healthy Thailand campaign. Food should be safe for domestic consumption as well as

for export. The government currently assigns responsibility to several agencies. In the

Ministry of Public Health these include the Food and Drug Agency, the Bureau of

Health Promotion, and the Bureau of Environmental Health. In the Ministry of

Agriculture, the agencies concerned are the National Bureau of Agriculture Commodities

and Food Standards, the Department of Livestock Development, and the Department

of Fisheries. Good coordination and collaboration among these concerned agencies

needs to be strengthened.

3.5 Emergencies

Thailand is prone to natural disasters, a fact demonstrated most tragically by the devastating

tsunami in December 2004 that struck the southern provinces of the country. The country

was affected again by heavy floods during August and September 2006, which hit 47

central and southern provinces and forest fire in the Northern Region in 2007. The Royal

Government of Thailand is self-reliant in disaster relief operations. WHO and the UN

Disaster Management Team have however, supported the country in assessing the health

situation and needs as well as in coordinating joint action for health.

3.6 Cross-border health risks

Thailand shares borders with the Union of Myanmar, the Lao Peoples Democratic

Republic, the Kingdom of Cambodia and Malaysia. However, border health concerns

are mainly located along the Thailand-Myanmar border and within the Mekong Basin

which spans the frontiers with Lao PDR and Cambodia. In the ten provinces of Thailand

that border Myanmar there are 401 000 registered migrants, about 117,000 registered

Thailand 11

in the camps, and an estimated 300 000 to 500 000 people who are not registered

citizens. Malaria is a particular concern in the provinces bordering Myanmar because

they account for nearly 70% of the disease burden in Thailand. On account of the

frequent and unregulated movement of migrants and their varying access to health

services, drug resistance to malaria and tuberculosis are a major concern. This is more

so since these migrants can potentially spread resistant strains to people in other parts

of the country.

Apart from six UN agencies, including WHO, about 25 international NGOs are

working along the Thailand-Myanmar border. Department for International

Development had provided funds to WHO Thailand for its Border Health Programme

during 20012005. While substantial progress had been made, the same cannot be

sustained without inter-agency collaboration and intersectoral support from the

Ministries of Public Health, Foreign Affairs, Interior and Labour.

3.7 Health promotion

Under the umbrella of Healthy Thailand, the Ministry of Public Health initiated nine

programme/project approaches. These are: Child Development, School Children in

Health Promoting Schools, Healthy Families for a Healthy Thailand, Healthy Cities,

Physical Activity and Diet for Health, Reproductive Health, Food Safety, Healthy Public

Toilet and Healthy elderly. Several health promotion programmes, campaigns and

initiatives have been launched in different parts of the country with either targeted

messages or target groups.

While there is adequate infrastructure within the MoPH to implement health

promotion practices and policies through 12 Regional Health Promotion Centres and

75 Provincial Health Offices, the biggest challenge is to establish effective collaboration

and partnerships with other sectors outside the MoPH. These include the Ministries of

Education, Interior, Social Development and Security, and Agriculture and Cooperation,

and NGOs and civil society.

Although the MoPH has a limited budget for developing health promotion, substantial

support is being provided by the Thailand Health Promotion Foundation, established by

the 2001 Health Promotion Foundation Act. Two per cent of the excise taxes on tobacco

and alcohol, or about US$ 55 million annually, has been allocated as revenue for the

Foundation, which serves as a catalyst for health promotion activities. The Foundation is

supervised by a governing board chaired by the Deputy Prime Minister.

In August 2005, the Sixth Global Conference on Health Promotion which yielded

the Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion was organized in Bangkok, Thailand.

Thailand is in the process of implementing the Bangkok Charter actions and

commitments with WHO support.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 12

3.8 Health systems

Health systems development and stewardship

Thailand has a developed health infrastructure, and good financial and health resources.

Access to basic health care has steadily increased over the past 30 years. The government

has accorded high priority to social health security to meet the goal of universal

healthcare coverage. However, efforts are needed to improve the quality of services

and to ensure the sustainability of the health system.

There is also the issue of inequitable access to quality health care in different parts

of the country. There are large gaps, for example, between Bangkok and the northeastern

region in the magnitude of health resource distribution. The Bangkok Metropolitan

Area has about one-fourth and one-tenth of the population per bed and per physician

respectively as compared to the corresponding figures for the Northeastern Region

(Table 1). While private hospital beds account for about 25% of the total, these mostly

serve a limited number of patients who can afford them.

The most recent Health Systems Reform began in 2000. The National Health

Systems Research Institute (HSRI) established the Health Systems Reform Office (HSRO)

to serve as the secretariat to the National Health Systems Reform Committee (NHSRC),

which plays a guiding role. With the involvement of society and community

organizations, the Committee drafted the National Health Bill policies to address the

health needs of the people, and to propose an essential health infrastructure that would

sustain the new health systems. After seven years of concerted efforts, the Bill was

finally approved by the Cabinet in March 2007.

The International Health Policy Programme (IHPP), a semi-autonomous

organization, was established in 2001, with joint collaboration by the Ministry of Public

Health and the HSRI. It aims to develop and strengthen national capacity in health

systems, policy research and international health. In 2003, the National Health Security

Office (NHSO) was established with the main responsibility of expanding the coverage

of health insurance or security to the people who have not been covered by any other

government health insurance scheme. It is also responsible for developing standardized

Table 1: Distribution of health resources classfied by region, 2004

Source: Report of Health Resources, Bureau of Policy and Strategy, MoPH

6

.

Thailand 13

benefit packages and financing and ensuring health security rights to target population

groups.

Considerable progress in health systems development particularly in expanding

health services notwithstanding, many national challenges remain. These include

improvement in the equity and efficiency of services among the poor and disadvantaged

groups of the population. At the same time, capacity building in the areas of financial

management, health policy development, healthcare system research, medical

anthropology, and health-related public laws is being enhanced.

With these initiatives Thailand has demonstrated its commitment to health systems

development. The National Health Act should generate healthy public policy that would

then be implemented by all sectors concerned. The National Health Act blends and

balances the philosophy of sufficiency economy and the principles of the Tenth

National Development Plan. Having learned from the experience of the World Health

Assembly, the National Assembly will aim to function effectively, in response to local

and national health needs. In conclusion, the health system in Thailand is geered

towards raising the level of happiness of the people and the quality of their life as

opposed to merely confining itself to the prevention and control of disease.

Health financing

(a) Health expenditure

The national health budget has increased from 5.8% of the total government expenditure

in 1993 to 7.6% in 2004 (Annex 3). As depicted in Table 2, about 60% of total health

expenditure comes from government sources, against 40% from private sources (out-

of-pocket and private prepaid plans). External aid in health is as low as 0.1%0.3% of

annual government health expenditure.

Table 2: Sources of health expenditure (%)

Sources: World Health Report,2006

7

.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 14

(b) Health insurance schemes

During 20022004 the budget allocation of the Ministry of Public Health for health

security accounted for 77.8% of total health budget (Annex 4). These funds supported

capitation for nationwide health services under the scheme for universal health care

coverage (UC), at that time called the 30-baht Scheme, including a special fund for

preventive and promotive health services. In 2004, the UC Scheme was estimated to

account for 75.2% of the total health insurance schemes in Thailand, and it covered a

population of about 47 million. Although the study showed the appropriate capitation

rate for the UC is Baht 1,510, the actual per capita payment in 2004 was Baht 1,309

(Table 3).

The UC scheme combined and amalgamated many healthcare coverage schemes

and only three public health insurance schemes remained. These were the Social Security

Scheme (SSS), Civil Servants Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) and the UC Scheme (UCS).

Other important achievements of UC include the continuously increasing utilization

rates of health care at district hospitals (from 14% to 22%) and at primary healthcare

facilities (from 22% to 26%) in 2001 and 2003 respectively, while utilization rates at

provincial hospitals were reduced by 50%

9

. Moreover, the catastrophic health

expenditure, among the group of 10-25% of non-food expenditure on health, was

reduced from 11.9% in 1996 to 7.6 in 2002, and, among > 50% non-food expenditure

group, from 1.4% to 0.5% during the same period

10

.

Table 3: Coverage of health insurance schemes in Thailand in 2004

*Due to overlap in coverage the totals may not add up.

Sources: Jongudomsuk, NHSO Report 2004

8

.

Thailand 15

Health systems and infrastructure

Health care in Thailand is organized and provided by both the private and public

sectors. The Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) is the principal agency responsible for

promoting, supporting, controlling and coordinating all health services for the people.

In addition, there are several agencies playing significant roles in providing health

services as well as health development. These include the Ministries of Defence, Interior,

and Education, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, state enterprises, and the

private sector. There are also a number of non-profit agencies that provide health

services to the people. The main sources of their funding are from the MoPH subsidized

budget or from international donors.

Health services in Thailand are generally classified into five categories according

to the level of care:

Self-care level (in the household).

Primary healthcare Level (village level: midwifery centre).

Primary care level (Tambon level: health centre).

Secondary care level (District level: community hospital).

Tertiary care (provincial level: provincial/regional hospital).

According to the Decentralization Act 1999, decision-making and management

authority has been decentralized to the community in response to a demand for local

government accountability and a role in national development. Hence, at the primary

health care and primary care levels, the Tambon Administrative Organizations (TAOs)

are the responsible units for disease prevention and provision of basic health services.

During the past 10 years, the number of private clinics and hospitals in Bangkok

and other provincial cities has rapidly increased. The total number of beds in these

health facilities accounts for about 20% of the total hospital beds. The proportion of

health service utilization by private and public services is 24% and 76% respectively

6

.

3.9 Human resource for health

In 2006 there were 25,932 physicians in Thailand, which is about 12,000 less than the

optimal requirement stipulated by WHO. The inequitable distribution of physicians

and other health personnel between urban and rural, and central and other regions

particularly the north-eastern region is taken into account. According to a Ministry of

Public Health report in 2005, about 76% of the people utilize the services at primary

healthcare facilities and district hospitals, which have no specialists. However, currently

about 77.7% of available physicians are specialists, in either area, who provide services

mostly in major hospitals.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 16

The problem of an acute shortage of physicians was exacerbated by a considerable

number of physicians and nurses having resigned from the public health system. Many

of them shifted to private hospitals. There was a net loss of physicians, between 194

(22.0%) to 756 (74.6%), during 20012003

11

. The principal reasons for their resignation

were improved educational opportunities, unsatisfactory hospital management of

government, higher pays, and better work conditions

12

. The biggest exodus was seen

in the three southernmost provinces, due to continous unrest situation in the areas. If

all requests for transfer from these provinces were granted, government hospitals and

clinics would lose 70% of their staff strength

13

.

Thailand, however, has the advantage of two important international HRH

networks, namely, the South-East Asia Public Health Institution Network (SEAPHEIN),

the Asia-Pacific Action Alliance on Human Resources for Health (AAAH) and South-

East Asian Regional Association for Medical Education (SEARME) being located in the

country, whose expertise it can be fully utilized.

Thailand 17

1. Partnership with UN and other international

development agencies

Partnership in health is a key component in the strategy for the progress of health

development in Thailand. The country has established viable mechanisms for

effective coordination and collaboration on two fronts:

Thailand receives support from development partners in terms of technical

and financial resources to strengthen national capacity in specific areas in

the health sector.

Thailand is also gradually becoming a development partner, like other middle

income countries such as Peoples Republic of China, Republic of Korea,

and others, by assisting developing countries, both within and outside the

region, through its foreign policy of forward engagement. It has established

the Thai International Technical Cooperation Agency (TICA) for technical

cooperation with other countries.

With regard to the first issue above, key partners of Thailand in health include UN

agencies (ILO, IOM, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNICEF and WHO),

development banks (The World Bank and Asian Development Bank), bilateral donors

(DFID, USAID, EU, etc.) and a few international NGOs. The Ministry of Public Health

has also established the Thailand MoPHUS CDC Collaboration Center (TUC) to

strengthen national capacity in the prevention and control of epidemics and emerging

communicable diseases.

Thailand has ratified a range of UN conventions and treaties, those on human

rights, child rights (CRC), discrimination against women (CEDAW), labour, environment

and tobacco being among them. In addition to UN country offices, the country hosts

a number of UN regional offices (23 UN agencies and two development banks) which

are based in Bangkok and provide services to neighbouring countries.

The United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF), referred to as

the United Nations Partnership Framework (20072011) in Thailand, has been

developed jointly with the Royal Thai Government (RTG). In keeping with the UNs

reform, alignment and harmonization agenda, it provides a framework to jointly plan

and support, in a complementary and coordinated manner, the national plans and

Development assistance and partnerships:

Aid flow, instruments and coordination

3

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 18

strategies in areas where the UN has mandated expertise and comparative advantage.

As a specialized agency, WHO is one of the signatories to this framework, which outlines

the following five areas of cooperation:

(a) Access to quality social services and protection;

(b) Decentralization and provincial/local governance;

(c) Access to comprehensive HIV prevention, treatment, care and support;

(d) Environmental and natural resources management, and

(e) Global partnership for development Thailands contribution.

With regard to the second item above, with large-scale financial contributions

from other development partners being reduced, these do not have permanent

programmes in Thailand any more. Assistance is provided to the country through

targeted areas of action and cooperation. Health-related areas that received financial

and technical cooperation from the development partners in 20042005 including

support for women and gender issues; HIV/AIDS treatment, prevention, and advocacy;

and support for improvement of land and water resources to reduce vulnerability to

natural disasters and enhance productivity.

The UNDAF 20022006 for Thailand was developed with the overarching goal

of promoting the reduction of disparity and ensuring sustainable human

development. An indicative programme resource framework, according to individual

agency mandates, was also made

14

. This is indicated in Table 4 below.

Table 4: UNDA Indicative Programme Resources Framework, 20022004

Thailand 19

2. Partnership with developing countries

Thailand has been active in a number of regional and sub-regional cooperation initiatives

with developing countries in many areas, including health. These initiatives have been

carried out through agencies, mechanism and other initiatives such as the Association

of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC),

Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS), Mekong-Ganga Cooperation (MGC), Ayeyawady-

Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) and the Bay of Bengal

Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMST-EC).

The Greater Mekong Sub-region, which comprises six countries along the Mekong

basin (Cambodia, PR China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam), builds strong

partnerships in social and economic cooperation. In the area of health, programmes

such as the Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance (MBDS), Mekong Malaria Programme

and Human Resource Development Projects are included. The Asia-Pacific Action

Alliance on Human Resources for Health (AAAH), its main office being located in

Thailand, is a response to the international recognition of the need for global and

regional action to strengthen country planning for HRH.

Thailand is the only non-member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD) that produced a report on Millennium Development Goals

(MDG) -8: The Global Partnership for Development. This goal sets targets for increased

Official Development Assistance (ODA), ensuring access for developing countries to

technology and essential drugs.

By engaging in the South-South development cooperation and taking a leading

role in regional and sub-regional cooperation initiatives, Thailand is actively sharing

with other countries its own knowledge of what it takes to reduce poverty rapidly,

improve health and education, and confront the challenges of environmentally

sustainable development. This cooperation policy has also led to an engagement in

programme development assistance to African countries, notably in the field of HIV/

AIDS prevention, in collaboration with UNDP.

3. Technical cooperation with other countries

During 20042006, a total of 602 Fellows from all Member countries of the South-East

Asia, Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean Regions visited Thailand to gain

experience in different medical and health fields. Their fields of study were health

systems, primary health care, health promotion, nursing care, laboratory investigation

and epidemiology. During 20052006 about 50 Thai experts were recruited as

consultants by WHO and other international health-related agencies to work within

and outside the Region. They contributed in varied sectors including health insurance,

quality assurance of laboratory services, disaster preparedness and response, registration

of medicines, HIV/STD, dengue prevention and control, and epidemiology training.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 20

4. WHO collaborating network

Currently Thailand has 33 designated and functioning WHO Collaborating Centres

and 35 Centres of Expertise. These centres provided training to national and international

fellows, conducted studies in areas identified or stipulated by WHO, and offered

reference laboratory services. A Network for WHO Collaborating Centres and Centres

of Expertise in Thailand (NEW-CCET) was established to share experiences and

strengthen institutional capacity. The National and Regional Experts System for South-

East Asia Region (NRES) was developed under the NEW-CCET. This system includes

Thai experts and institutional databases. This is a good initiative, but to be fully functional,

it requires improvement and sustainable funding. The role of the NEW-CCET is being

reviewed.

Thailand 21

1. Work of the WHO Country Office encompasses:

Advocacy, technical advice, and technical services/support to the government,

UN agencies and other development partners on health and health-related

matters;

Partnerships and coordination with other stakeholders for effective response,

especially in tackling health issues;

Identifying Thai technical expertise and facilitating the sharing of that expertise

with neighbouring countries, other Regions, and also globally;

Providing administrative support to the Regional Office, HQ and other

Country Offices in arranging fellowships, consultations, conferences and

technical meetings and facilitating laboratory services to Bhutan, Myanmar

and Nepal under the polio eradication programme;

Disseminating WHOs policies and positions through the media and other

communication channels, and

Providing administrative support and common services to WHO sub-regional

health units that are based in Bangkok.

2. Focus of WHOs collaboration with Thailand

WHOs collaboration with Thailand is based on the WHO Country Collaborative

Programme which is developed on a biennial basis. The current CCS 20042007 was

used as a framework and guideline for the development of the biennial programme

budget and workplans in the 2004-2005 and 2006-2007 bienniums. The Country

Office focused on supporting policy development, providing technical advice, and

developing norms and guidelines. In accordance with the CCS 2004-2007 and in

continuation of some priorities from the 2004-2005 biennium, the WHO Country

Office has in the current biennium focused on the following areas of work:

Communicable disease prevention and control, including epidemic alert and

response;

Prevention and management of chronic and non-communicable diseases,

and health promotion;

Current WHO cooperation

4

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 22

Health research, evidence, and health systems development;

Emergency preparedness and cross-border health;

Immunization and vaccine development;

Technical cooperation among countries, and

Health and environment.

Previous CCSs have helped to focus WHO collaboration with the RTG on a few

priority areas where the Organization has an advantage and for which it receives requests

from the government. Nevertheless, additional efforts are required to streamline the

number of activities carried out within the ambit of these broad priority programmes.

The WHO Country Office still issues a large number of contracts to implement these

activities. The administration of these contracts require considerable time and effort

on the part of the Country Office staff.

In order to ensure that the research and studies undertaken with WHO support

are applied to developing and monitoring health programmes, principal investigators

were requested, at the end of 2006, to present their work at the WHO Country Office.

Many of these were found to be valuable, and feasible to implement. Some have been

replicated within the MoPH and other related institutions. However, it will be useful to

review the studies undertaken and models developed to ensure that there is no

duplication, and that they are practical and feasible.

3. Funding of WHO collaborative programmes.

Budgetary support to carry out these programmes comes from WHOs assessed and

voluntary contributions, and from other international agencies outside WHO. The assessed

contribution for the WHO Country Programme in 20042005 was US$ 5.18 million. In

addition, about US$ 1.69 million in voluntary contribution was mobilized for Thailand

from across WHO, including US$ 281,000 for the tsunami relief operation. There has

been an increase by 11% in assessed contributions for 20062007 to US$ 5.78 million,

following the decision of the 2005 World Health Assembly to increase the assessed

contributions by Member States. In addition to this assessed contribution, the Country

Office has till date received about US$ 23 million through voluntary contributions.

4. Fellowships

From the 19981999 bienniums till the current biennium, the WHO Country Office

has provided 36 long-term fellowships to staff of the Ministry of Public Health and

university. Fellows have completed courses leading to five certificates, 17 Masters degrees

and 14 PhDs in the field of public health, HRH, health economics, health services

management, international health, health policy, health planning and financing,

epidemiology, policy analysis, health promotion, medical anthropology, health service

research, public health nutrition and Genetic Epidemiology.

Thailand 23

5. Regional Sub-units

In addition to the Country Office, WHO has two Regional Sub-units in Thailand:

Mekong Malaria Programme: This is a bi-regional project based in Thailand

to coordinate WHO activities in countries of Mekong Basin.

WHO Regional Sub-unit for Communicable Disease Control (CSR Sub-

unit): The Regional Director decided in 2005 that a CSR Regional Sub-unit

was to be established in Bangkok. The rationale behind this unit being located

outside the Regional Office was its locational advantage, its infrastructure in

terms of transport and communications, and the technical expertise that

Thailand possessed. The decision to establish a sub-unit was in keeping with

the decentralization policy initiated by the Regional Office and the felt need

to establish a regional presence in Bangkok to better interact with agencies

in that part of the Region.

The Sub-unit will operate within the broader context of supporting

countries to develop the required core capacities for: a) implementing the

International Health Regulations (IHR); b) strengthening the Field

Epidemiological Training Programme (FETP); c) the Asia-Pacific Strategy for

Emerging Diseases (APSED); d) developing early warning systems and risk

assessment of potential public health emergencies of international concern

(PHEICs) and response, and e) promoting research, particularly evaluative

research.

At the same time, Thailand will desire maximum benefit of technical

support from the CSR, and the Sub-unit will engage with the MoPH to support

other Member States as well. Although this sub-unit is established under the

Regional Offices technical and administration settings, its operations may

go beyond the Region to assist countries in the Greater Mekong Sub-region,

whenever there is a cross-border outbreak of an important disease.

6. Staffing

Thailand has a relatively small office in terms of number of technical staff. Moreover, it

is able to provide and share technical expertise, particularly with its neighbouring

countries. WHO has played an important role in identifying and facilitating this sharing.

Currently there are only two international professional staff (WR and the

Administrative Officer), six national professional officers and 13 national support staff

in the Thailand Country Office. Additionally, the Regional Sub-units have three

international Professional staff and one General Service staff. The support for the Sub-

unit is covered by funds from outside the country budget. The organogram is provided

in Annex 8.

WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2008-2011 24

7. Office premises

The Ministry of Public Health has provided office space gratis for the WHO Country

Office as well as for the CSR Regional Sub-unit. The Mekong Regional Sub-unit is

located in the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok.

8. Information and communication technology

Although Thailand has very good communication facilities, the Country Office as well

as the CSR Sub-unit have been connected with the Global Private Network (GPN)

enabling faster connections with the Regional Office and Headquarters. It is equipped

with tele and video conference facilities. In view of Thailands strength in IT expertise,

the Regional Office may consider decentralizing the maintenance and updating of the

ITC system to the Country Office for reasons of expediency.

9. Use of CCS

Overall, the current CCS has been well utilized by the WHO Country Office to develop

workplans that align with the National Health Plan and other national health and

development frameworks. Whether the priorities identified in the previous CCSs have

informed the regional or global strategies and priorities still remains an issue.

The extent to which the priorities identified in the CCS were implemented in line

with the six core functions of WHO is presented in Table 5. The relative weight assigned,

in terms of the number of pluses (+) in the table, is based on the scope of work

undertaken in the biennium 200405 and calendar 2006.

Table 5: Performance in priority areas, in relation to

WHO core functions (20042007)

Thailand 25

1. Global challenges in health

The General Programme of Work (GPW) is the highest-level policy document of WHO.

The Eleventh GPW (2006-2015) sets out the direction for international public health

for the period of 2006 through 2015. The document notes that though there have