Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 S0167487011001589 Main

Uploaded by

Billy CooperOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 S0167487011001589 Main

Uploaded by

Billy CooperCopyright:

Available Formats

Action speaks louder than words: The effect of personal attitudes and

family norms on adolescents pro-environmental behaviour

Alice Grnhj

, John Thgersen

Aarhus University, School of Business and Social Sciences, Denmark

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 2 May 2011

Received in revised form 30 September

2011

Accepted 1 October 2011

Available online 13 October 2011

JEL classication:

P46

PsycINFO classication:

3900

Keywords:

Consumer behaviour

Attitudes

Socialisation

Parenting

Environmentalism

a b s t r a c t

Adolescents environmentally relevant behaviour is primarily carried out in a family con-

text. Yet, it is usually studied and discussed in an individual decision-making perspective

only. In a survey involving 601 Danish families, we examine to which extent adolescents

everyday pro-environmental behaviour is the outcome of their own pro-environmental

attitudes or the product of social inuence within the family, that is, a reection of the

dominating values and norms in the family group as manifested most clearly in their par-

ents attitudes and behaviour. In addition, we examine the moderating effects of two family

characteristics, parenting style and the generation gap (parentchild age difference), on

the relative weight of adolescents personal attitudes vs. social inuences within the family

as predictors of adolescents pro-environmental behaviour. Results show that the adoles-

cents pro-environmental behaviour is heavily inuenced by the dominating norms within

the family and in particular by how strongly they are manifested in their parents

behaviour.

2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Many of the most important decisions and activities for the health and wellbeing of individuals are carried out in a family

context. For this reason, the family plays a central role when promoting health and wellbeing of individuals and for society in

general. Most decisions about consumption and other private economic affairs are made in families, children are born and

raised here, and they are socialised to become (more or less) responsible citizens in their family. In this article, we explore

this last function of the family in the perspective of the societal goal of achieving a more sustainable consumption pattern.

In order to promote the development of pro-social consumption practices, such as responsible waste handling or careful

use of non-renewable energy sources, we need to know how such practices are established in a (young) person. Consumer

socialisation theory (e.g., John, 1999; Ward, 1974) suggests that the family, and especially parents, play a key role for teach-

ing and passing on pro-environmental consumer practices to the next generation. Similarly, developmental psychology has a

strong focus on parental inuence when discussing value similarity between generations (e.g., Whitbeck & Gecas, 1988) and

the development of pro-social values in children (e.g., Kasser, Ryan, Zax, & Sameroff, 1995). However, there is a lack of re-

search documenting the importance of family inuences on childrens pro-environmental practices. Families differ in many

0167-4870/$ - see front matter 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.10.001

Corresponding author. Address: Aarhus University, School of Business and Social Sciences, Haslegaardsvej 10, 8210 Aarhus V, Denmark. Tel.: +45 8948

6471.

E-mail address: alg@asb.dk (A. Grnhj).

Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Journal of Economic Psychology

j our nal homepage: www. el sevi er. com/ l ocat e/ j oep

ways, some of which may moderate parental inuence in this area. Obvious examples are the generation gap (i.e., the size

of the age difference between parents and children), and the socialisation norms guiding relationships between parents and

their children within the family, often referred to as parenting style (Baumrind, 1971; Carlson & Grossbart, 1988; Grusec &

Kuczynski, 1997; Maccoby, 2006). Furthermore, individual characteristics of the parent and child (e.g., the extent to which

the child identies with the parents) may also play a role for the extent of value transmission (Whitbeck & Gecas, 1988).

However, the role of such inuences in the transmission of pro-environmental norms and behaviour to children has hardly

been researched at all.

The question of how pro-environmental behaviour is established is especially urgent in the light of mounting evidence

suggesting that young people are more reluctant to commit to pro-environmental behaviour than older people, in spite of

often holding more favourable environmental attitudes (Diamantopoulos, Schlegelmilch, Sonkovics, & Bohlen, 2003; Euro-

pean Commission, 2008a, 2008b; Grnhj & Thgersen, 2009; Johnson, Bowker, & Cordell, 2004). There is even evidence that

the young generations concern for the environment, conservation behaviours and ascription of personal responsibility for

environmental protection have declined during the last three decades (Wray-Lake, Flanagan Constance, & Osgood, 2010).

Hence, there is a need for research, which can inform policy about required steps to educate or encourage young people to

engage in environmentally benign activities, including research on the formation of a pro-environmental behaviour pattern

in a young age. Our introductory reections on the importance of the family context suggest that such interventions need not

only be targeted directly at the young individuals, but that young people might also, and perhaps sometimes better, be inu-

enced indirectly through their parents or other inuence agents.

1.1. The family as a context for pro-environmental consumer socialisation

In consumer research, socialisation theories are often used as a theoretical backdrop against which the processes by

which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes relevant to their functioning as consumers in the marketplace

(Ward, 1974, p. 24) are investigated. Although prone to other inuences, such as media, peers, and school, parents have a

pivotal role in the primary socialisation of children and adolescents, including the transmission of consumer related orien-

tations (John, 1999; Moore & Wilkie, 2005; Ward, 1974). Parental inuence has been documented at various levels of con-

sumer behaviour, such as attitudes, values and beliefs about the marketplace (e.g., Moore-Shay & Lutz, 1988; Obermiller &

Spangenberg, 2000; Youn, 2008), and behaviour such as product and brand choice (e.g., Hsieh, Chiu, & Lin, 2006; Mandrik,

Fern, & Bao, 2005; Moore, Wilkie, & Lutz, 2002; Olsen, 1993). In this connection, consumer behaviour refers to both phys-

ical and mental acts of individuals and small groups regarding orientation, purchase, use, maintenance and disposal of goods

and services (Antonides & van Raaij, 1998).

The within-family transmission of information, beliefs, attitudes and behaviour from one generation to the next is often

referred to as intergenerational (IG) inuence, and constitutes an important mechanism by which culture is sustained over

time (Blackwell, Miniard, & Engel, 2006; Moore, Wilkie, & Lutz, 2002). IG inuence also includes the notion of reverse soci-

alisation which refers to the consumption-related inuence going from children to their parents and reciprocal, or bidirec-

tional, inuence (Ekstrm, 1995). There is some evidence of reverse and reciprocal family inuences, for instance with respect

to children teaching parents about products involving the use of new technologies (Ekstrm, 1999; Moore et al., 2002). It has

also been suggested that children may act as catalysts with respect to their parents environmental learning and involvement

in green behaviour (Easterling, Miller, & Weinberger, 1995), and some studies have found that children bring home envi-

ronmental issues learnt in school for discussion at home, resulting in the change of household practices (Ballantyne, Fien, &

Packer, 2001; Grodzinska-Jurczak, Bartosiewicz, Twardowska, & Ballantyne, 2003). Ekstrm (1995) and Grnhj (2007) also

found instances of reciprocal and reverse pro-environmental inuence with respect to every-day household activities such as

reducing water and electricity consumption and recycling. However, so far the evidence for reverse and reciprocal environ-

mental socialisation is quite weak and recent studies suggest that in this domain, the direction of IG inuence primarily runs

from parents to their children (Gotschi, Vogel, & Lindenthal, 2010; Grnhj, 2007; Grnhj & Thgersen, 2009).

Consumer learning in the context of family life is generally thought to occur through observation, reinforcement pro-

cesses, and family members social interaction, as well as by shopping and product use/consumption experiences (Moschis,

1987; Moore-Shay & Lutz, 1988; John, 1999). An important part of parents transmission of consumer skills to their children

is setting examples for good behaviour. Thus, appropriate behaviour is to a high extent learnt through observing others

(i.e., modelling), since retaining observational information as a guide for subsequent action reduces needless errors signi-

cantly (Bandura, 1977). In a family context, children are intensely exposed to parents behaviour and preferences, which

eventually results in their perception of parents consumption related behaviour as the acceptable norm of conduct, although

some opposition to parental norms is also common, especially during the late teenage years (Kuczynski & Parkin, 2006).

Despite the widespread acknowledgement of the importance of modelling for consumer learning, there are few empirical

studies of modelling within consumer socialisation research and they mostly study the phenomenon in an indirect way. For

example, stronger IG inuence has been associated with more visible (e.g., toothpaste) compared to more invisible

brands (e.g., canned vegetables) consumed in the home (Moore-Shay & Lutz, 1988). Also, stronger IG effects have been found

for concrete products and brand preferences than for abstract (consumption) values (Obermiller & Spangenberg, 2000).

Moore and colleagues (Moore, Wilkie, & Alder, 2001; Moore et al., 2002) note that participation in the households shopping

and observation of products and brands in the home are central to IG transmission of brand preferences and choices, in addi-

tion to direct communication about preferences and practices. Abstract consumption orientations and values are more

A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302 293

difcult for children to observe and learn, except when a familys endorsement of specic values entails visible consequences

(e.g., going to church due to the parents religious values).

With respect to other processes of inuence and consumer learning, consumer socialisation studies have assessed the im-

pact of family communication and rearing styles on parent to child inuences. Typologies of general parenting styles are

used to predict socialisation outcomes in children. These typologies largely differ in the extent to which they encourage

or restrict consumption autonomy and whether parental communication is characterised by warmth or hostility (e.g., Carl-

son & Grossbart, 1988; Moschis, 1985). Parenting practices have been found to differ in the extent to which they facilitate

consumer knowledge and consumer related skills and values in children. For instance, a concept-oriented communication

style that is characterised by encouraging negotiation and promoting child autonomy has been shown to foster consumer

scepticism towards advertising (Mangleburg & Bristol, 1998) and less materialism in adolescents (Moschis & Moore,

1982). Within developmental psychology, parenting styles have been related to childrens moral development, pro-social

behaviour (e.g., Grolnick, Deci, & Ryan, 1997; Maccoby, 2006) and materialistic orientations (e.g., Kasser et al., 1995). There

is general support for the notion that authoritative parenting facilitates childrens pro-social development and behaviour.

Authoritative parenting is an interaction style that encourages childrens independence and individuality while at the same

time enforcing certain standards of behaviour in an open communication style (Baumrind, 1971). Related to this, Kasser et al.

(1995) found that mothers of materially oriented children scored lower on warmth and democracy than those of less mate-

rialistic youngsters. However, developmental psychologists have also suggested that, especially when it concerns adoles-

cents, an examination of parenting practices, in addition to interaction styles, is needed to account for socialisation

outcomes in adolescents (Carlo, McGinley, Hayes, Batenhorst, & Wilkinson, 2007).

1.2. Family norms and adolescents pro-environmental consumption practices

Young consumers are assumed to be particularly receptive to reference group inuence shaping their consumption

behaviour (Park, 1977), and there is no reason to expect this to be any different for pro-environmental behaviour. Previous

research suggests that the extent to which one imitates the behaviour of others depends on who these others are, including

how similar they are to oneself in terms of age, personality, attitudes, etc. (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Festinger, 1954; Gold-

stein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008; Park, 1977). Thus, especially considering young peoples quest for independence during

the teenage years, parents, being much older, may not necessarily be the most inuential signicant others to adolescents.

On the other hand, Goldstein and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that the importance of who is often overridden by the

importance of where, that is, by situational inuence. Thus, in the context of the family and with respect to activities car-

ried out at home, adolescents may be strongly inuenced by the norms of their parents, who are and have (usually) always

been part of their immediate surroundings and are their rst and lifelong reference group.

Though rarely applied in a family context, normative social inuence has received extensive attention in social psychol-

ogy (e.g., Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Kallgren, Reno, & Cialdini, 2000). Cialdini and his colleagues (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren,

1990; Kallgren et al., 2000) distinguish between descriptive norms, the norms of is what is commonly done, and injunc-

tive norms, the norms of ought what is commonly approved or disapproved. Both types of normative inuence are likely

to be highly relevant for understanding how parents inuence their children, for example to become environmentally

responsible citizens. In particular, descriptive norms play a key role in the previously mentioned behavioural modelling pro-

cesses that have been identied as one of the central pathways of (consumer) socialisation and IG transmission (Bandura,

1977; John, 1999; Ward, 1974).

Quite a few studies have examined the inuence of parental behaviour and norms on childrens attitudes and behaviours

with respect to health-related behaviours such as healthy eating and physical activity, as well as problematic behaviours

such as smoking, excessive drinking and drug abuse (e.g., Baker, Little, & Brownell, 2003; Baker, Whisman, & Brownell, 2000;

Musick, Seltzer, & Schwartz, 2008; Wood, Read, Mitchell, & Brand, 2004). For instance, Baker et al. (2003) found that adoles-

cents perceptions of parents and peers perceived behaviour (descriptive norms) and approval (injunctive norms) inuence

their attitudes to healthy eating and physical activity. Perceived parental disapproval has also been found to curb late ado-

lescents and young peoples alcohol consumption and drug abuse (Musick et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2004) and to moderate

the effect of peer inuence on adolescents consumption of alcohol (Wood et al., 2004).

A large number of studies across a wide range of behavioural elds have found that social norms affect pro-environmental

behaviour (e.g., Biel & Thgersen, 2007; Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, 1991; Goldstein et al., 2008; Gckeritz et al., 2010; Nolan,

Schultz, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2008; Schultz, 1999; Thgersen, 2008). In this context, the role of social norma-

tive inuences between generations has only been touched upon to a limited extent. However, recent studies support the

notion that family inuences are of central importance also in this area (Baslington, 2008; Gotschi et al., 2010; Haustein

& Hunecke, 2007). A study of German high school students purchase of organic food products that distinguished between

the normative inuence of each parent, siblings, friends, classmates, and teachers found that, while controlling for the stu-

dents own attitudes to organic products and specic cultural patterns (i.e., interest in health-related activities), primary

socialisation agents (parents) exert more inuence than secondary (peers and school teachers) (Gotschi et al., 2010). Also,

recent transportation research suggests that children learn to like various transportation modes through both primary

and secondary agents of socialisation and that both parental and peers are inuential in childrens attitudes towards using

cars for transportation (Baslington, 2008; Haustein & Hunecke, 2007). Baslington (2008) also found that a signicantly higher

294 A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302

number of children raised in a car-free family claimed to be able to live happily without a car than children raised in a

family with one or more cars.

2. Hypotheses

Parents are likely to inuence their children to act in more or less pro-environmental ways. Although socialisation theory

also discusses child-to-parent inuences, in this domain, and based on the ndings of consumer socialisation theory related

to proenvironemental socialisation, social norms theory and previous studies in the environmental eld (Grnhj & Thger-

sen, 2009), we expect substantial parental inuence on childrens pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour. Like in other

contexts, the importance of these normative inuences may differ between different environmentally relevant activities and

they may be contingent of various characteristics of the specic family. In this study, we focus on adolescents, that is, older

children who are still living at home with their parents, but who are mature enough to have responsibilities in the household

and, not least, their own opinions on many things.

In the everyday life of a family, environmental issues and specic environmentally relevant behaviour may sometimes be

on the agenda in conversations among family members, for example, when a parent wants to correct the behaviour of a child

(or vice versa). However, conversations such as these are probably relatively rare in most families. Compared to this, most

adolescents are exposed much more intensely to their parents environmentally relevant behaviour. Hence, it seems likely

that in most family contexts there are stronger and more frequent behavioural than verbal cues to the familys environmen-

tal norms. Hence, we would expect family descriptive norms to exert a stronger inuence than family injunctive norms on

adolescents pro-environmental behaviour.

Hypothesis 1.1. After controlling for the adolescents own attitude to the specic behaviour, adolescents pro-environmental

behaviour (e.g., buying eco-friendly products, handling waste responsibly, curtailing electricity) depends on the dominant

norms in the family, as reected in parental attitudes and behaviour.

Hypothesis 1.2. Adolescents pro-environmental behaviour (e.g., buying eco-friendly products, handling waste responsibly,

curtailing electricity) is more strongly inuenced by descriptive norms in the family, as reected in parental behaviour, than

on family injunctive norms, as reected in parental attitudes to specic pro-environmental behaviours.

As already mentioned, families differ in a whole range of ways, some of which may have implications for the relative

weight of, on the one hand, different types of norms (descriptive vs. injunctive) and, on the other hand, norms vs. the ado-

lescents personal attitude to the specic behaviour. For example, we suggested earlier that the size of the generation gap

or age difference between parents and their children might moderate their mutual social inuence. This age difference obvi-

ously differs widely across families, some people becoming parents at an earlier age than others. The generation gap

hypothesis suggests that younger parents exert a stronger inuence on their teenage children than older parents, everything

else being equal.

Hypothesis 2. The larger the age difference between parents and their adolescent, the weaker inuence norms in the family

have on the childs pro-environmental behaviour.

Also, given the importance of parents as socialisation agents, there is reason to expect an effect of the parenting style on

the relative weight of family norms vs. the childs personal attitudes as determinants of behaviour. As noted by Grolnick et al.

(1997, p. 135), socialisation agents may be able to force children to carry out behaviours, but the real goal is for children to

carry them out volitionally. In this connection, Grolnick et al. (1997) especially emphasize the importance of parental

autonomy support. Whereas an autonomy supporting environment may encourage the development of pro-social compe-

tencies and orientations in general and therefore have a positive inuence on adolescents engagement in eco-friendly

behaviour (cf. Gagn, 2003), it is also likely that it will make the adolescent more independent. Thus, autonomy support

may encourage the child to rely more on his or her own attitude rather than the prevailing family norms.

Hypothesis 3. An autonomy supporting parental style increases the importance of the young persons own attitude relative

to the dominant norms in the family for the performance of specic pro-environmental behaviours.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

A total of 601 Danish families were interviewed by means of Internet-based questionnaires. The survey was carried out by

a professional market research institute, TNS Gallup, amongst members of the institutes Internet panel. The panel is repre-

sentative of the Danish population in terms of socio-economic background characteristics. Two representatives of each

family, a parent and an adolescent, each individually completed a questionnaire related to three pro-environmental con-

sumption practices: buying organic/environmentally friendly (green in the following) products, curtailing electricity use

A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302 295

and source-separation of waste (for recycling), activities that represent different parts of a consumption cycle purchase,

use, and disposal (Antonides & van Raaij, 1998). The aim was to include environmentally relevant activities for which we

could be reasonably certain that both parents and adolescents would be involved in most families. Moreover, the activities

were selected as representative of areas in which households can make signicant contributions in terms of improving the

sustainability of private consumption (OECD, 2002).

The nal sample consisted of 1202 parents or children (in pairs). The composition of the sample was 293/308 boys/girls,

with an age range from16 to 18, and 243/358 father/mothers with an age range from31 to 68 (Table 1). Hence, there is a slight

overrepresentation of girls and mothers in the sample. Also, only 2% of non-ethnic Danes were represented, while the propor-

tion of non-ethnic Danes in the population is around 10% (Danmarks Statistik, 2009). As a requirement for participation, the

participating child had to be between the age of 16 and 18 and two adults (both parents, or a parent and stepparent) had to be

living with the adolescent. These requirements, in addition to the requirement for two responses (a parent and a child) made

the recruitment of families challenging and the resulting response rate quite low (28%). Hence, and since we were recruiting

families, and not individuals, the sample cannot be said to be representative of the Danish population. However, it has a com-

position, which is sufciently varied in terms of socio-economic background characteristics for the present purpose.

3.2. Measures

Questions included attitudes and behaviours with regard to each of three behaviours (i.e., buying green products, recy-

cling, and curtailing electricity use). In addition, in case of the young respondent, questions included perceptions of his or

her parents attitudes and behaviours with respect to the same activities.

The following behaviour items were included in both parent and child questionnaires: When you do shopping for the

family, how often are the goods that you buy organic or environmentally friendly, How often do you make an effort to save

on electricity consumption at home, and How often do you sort the waste correctly. Responses were measured on

a 5-point scale from 1 = always to 5 = never. Since about one third of the youngsters claimed never to do any shopping

for the family, they (and their parents) were excluded from the analysis regarding buying green products.

In addition, the adolescents were asked to assess their parents frequency of behaviour with respect to the three behav-

iours, using the same format except that you was replaced by your mother and your father. Cronbach alpha for the

perception of parents behaviour scale is low for electricity saving (.56), but high for the other two behaviours (.87 and

.92). The reporting parent was also asked to assess his or her spouses frequency of behaviour with respect to the three

behaviours, using the same format except that you was replaced by your spouse. Also in this case, Cronbach alpha for

the two-item (reported for self and spouse) scale is low for electricity saving (.58) and high for the other two behaviours

(.82 and .91).

Both the parents and the childs attitudes towards each of the three behaviours were measured on three 7-point semantic

differential scales with the extremes 1 = good/benecial/wise and 7 = bad/detrimental/unwise (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Cronbach alphas for these attitude constructs are in the range from .89 to .93.

The adolescents also reported their perception of the attitude of the parent who also participated in the study, and like-

wise the parent reported the attitude of his/her spouse, in both cases on one item for each of the three behaviours on a

7-point scale with the extremes 1 = positive and 7 = negative. In the following analyses, the former of these is used to rep-

resent adolescents perception of their parents attitudes. The latter item was used to measure the level of agreement be-

tween parents (as perceived by the reporting parent), by subtracting the reported spouse attitude from the average of the

three items measuring the reporting parents own attitude.

Based on Deci and Ryans (1985) self-determination theory, the adolescents were asked about their perception of their

parents autonomy support. Eight items from Deci and Ryans (2008) perception of parenting style instrument, college-stu-

dent version for late adolescents or older, were included; for example: My mother (father) helps me to choose my own

direction. Cronbachs alpha for the autonomy support scale is .81.

4. Analyses and results

The data analysis and hypothesis tests were done by means of structural equation modelling (SEM) using AMOS 16 (Ar-

buckle, 2006). In SEM, the measurement model is a conrmatory factor analysis (CFA) model and the theoretical constructs

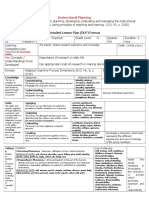

Table 1

Background.

N (%) Age M (st. d.) Education

*

M (st. d.)

Fathers 243 (20.2) 49 (5.7) 4.1 (1.7)

Mothers 358 (29.8) 45.6 (4.4) 4.3 (1.4)

Sons 293 (24.4) 16.9 (0.8)

Daughters 308 (25.6) 16.9 (0.8)

*

1 = Secondary school; 2 = upper secondary school; 3 = vocational education (trainee/

apprenticeship); 4 = some college/university (2 years); 5 = college/university (4 years);

6 = college/university (>4 years).

296 A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302

are latent factors extracted from the manifest variables (Bagozzi, 1994). The main advantage of SEM is that it is possible to

explicitly account for measurement error when a latent variable of interest is represented by multiple manifest variables.

Measures of how well the implied variancecovariance matrix, based on the parameter estimates, reects the observed sam-

ple variancecovariance matrix can be used to determine whether the hypothesised model gives an acceptable representa-

tion of the analysed data. In the analyses reported below, the usual assumptions about a simple structure factor pattern in

the measurement model and uncorrelated item error terms were applied.

4.1. Conrmatory factor analyses

Bivariate correlations between the latent constructs based on CFA are shown in Table 2.

The t indices show that the CFA models for recycling and green buying t the data well, but less well for electricity

saving. Overall, the correlations between constructs are also more modest for the latter than the two former behaviour(s).

Together, this indicates that the share of error variance is higher for electricity saving than for the other two behaviours, sug-

gesting it has been more difcult for participants to answer the questions regarding electricity saving. Apparently, electricity

saving is less salient than recycling and buying green products in the studied context.

A number of interesting observations can be read from the correlation matrices. In all three cases, adolescents behaviour

correlates signicantly with both their own attitude towards the behaviour and all indicators (except for one case) of dom-

inant family norms. The variable that correlates most strongly with adolescents behaviour in all three cases is a descriptive

norm indicator: their perception of their parents behaviour. Adolescents perception of their parents behaviour correlates

more strongly with their own behaviour than their perception of their parents attitude towards the same behaviour (indi-

cator of family injunctive norms) and the same is true when parent-reported attitudes and behaviours are used as indicators

of family norms. The parents self-reported attitude towards electricity saving is the only one among these indicators that is

completely unrelated to his or her childs behaviour.

There is a strong, positive correlation between the two descriptive norm indicators, parent-reported behaviour and the

childs perception of his or her parents behaviour, in all three cases. The same is true for the two injunctive norm indicators

with regard to buying green products. For the other two behaviours, these two indicators are only weakly correlated. The

relatively high agreement between parents and children with regard to the parents behaviour, and lower agreement with

regard to their attitudes, is consistent with the studied behaviours being visible in the family context, while attitudes are not.

The stronger correlation for attitudes towards green buying suggests that the families have talked more about this than

about the other two issues.

Table 2

Correlations between latent variables.

Mean Std.

deviation

Child

behaviour

Child

attitude

Perceived parent

behaviour

Perceived

parent attitude

Parent

behaviour

Parent

attitude

Parent dis-

agreement

Recycling Mean 2.93 1.77 2.44 2.28 2.00 1.46 0.58

Std.

deviation

1.47 1.15 1.38 1.54 1.15 0.87 1.31

Electricity saving

child behaviour

3.04 1.03 1.00 0.39 0.84 0.56 0.43 0.19 0.18

Child attitude 1.38 0.70 0.26 1.00 0.40 0.53 0.36 0.27 0.16

Perc. parent

behaviour

2.21 0.86 0.45 0.20 1.00 0.69 0.55 0.26 0.25

Perc. parent attitude 1.63 1.02 0.12 0.21 0.60 1.00 0.43 0.27 0.27

Parent behaviour 2.25 0.73 0.25 0.05 0.74 0.25 1.00 0.44 0.48

Parent attitude 1.17 0.46 0.00 0.09 0.11 0.16 0.21 1.00 0.05

Parent

disagreement

0.59 1.15 0.20 0.13 0.23 0.11 0.33 0.02 1.00

Green buying

Child behaviour 3.31 1.18 1.00

Child attitude 2.31 1.37 0.58 1.00

Perc. parent

behaviour

3.02 1.07 0.77 0.59 1.00

Perc. parent attitude 2.86 1.77 0.57 0.60 0.77 1.00

Parent behaviour 2.96 0.80 0.55 0.47 0.80 0.65 1.00

Parent attitude 2.31 1.26 0.37 0.49 0.53 0.54 0.64 1.00

Parent

disagreement

0.66 1.49 0.14 0.12 0.24 0.24 0.26 0.04 1.00

Note: Correlations > |.10| are signicant at p < .05. In the top half of the table, estimates above the diagonal represent responses regarding recycling, and

estimates below the diagonal represent responses regarding electricity saving. Electricity saving and recycling: N = 601. Green buying: N = 405. Fit indices:

electricity saving: Chisquare = 210.449, 48 d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 94; RMSEA = .075 (90% condence interval: .065.083). Recycling: Chisquare = 122.421, 47

d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 99; RMSEA = .052 (90% condence interval: .041.063). Green buying: Chisquare = 100.218, 47 d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 99; RMSEA = .053

(90% condence interval: .039.067).

A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302 297

Notice also that the childs perceptions regarding his or her parents attitude and behaviour are strongly and positively

correlated in all three cases, and more strongly than the parents self-reported attitudes and behaviours. This suggests that

children (a) implicitly expect their parents to be consistent in terms of attitudes and behaviour and (b) to some extent infer

their parents attitudes and, hence, family injunctive norms, from the parents behaviour.

We included an indicator of parental disagreement regarding the three behaviours. According to Table 2, parental agree-

ment is positively correlated with and disagreement tends to reduce the childs inclination to act in an environmentally

responsible way.

These correlations are consistent with Hypotheses 1.1 and 1.2, with the reservation that we did not control for other vari-

ables. In the next step, we will do that when presenting the results of structural equation modelling.

4.2. Structural equation modelling

Table 3 reports the results of structural equation analyses predicting each of the three adolescent behaviours and using all

other variables included in the CFAs as predictors.

Also after controlling for all other included variables, the strongest predictor, by far, for all three behaviours is the ado-

lescents perception of his or her parents behaviour, or the dominant descriptive norms in the family. After controlling for

this variable, the effects of all other variables representing norms in the family are suppressed, for the adolescents percep-

tion of his or her parents attitudes to the extent that it changes sign. Hence, it seems that all the normative inuences in the

family, for this category of behaviours, are mediated through descriptive norms as reected in the parents behaviour. Com-

pared to the normative inuence, the childs own attitude towards the behaviour plays a minor, although signicant role.

These results conrm Hypotheses 1.1 and 1.2.

A possible critique of these results is that adolescents report biased perceptions of their parents attitudes and behaviour

that do not only reect their true subjective norms, but also self-justication in the form of interpreting ambiguities in

parental attitudes and behaviours in a way that makes them more consistent with the childs own attitudes and behaviour.

To counter such critique, we also report the results of structural equation modelling where family norms are represented by

the parents reports only, that is, leaving out adolescents perceptions of their parents attitudes and behaviour (Table 4).

Not surprisingly, when normative factors are measured by reports by the parents, rather than being reported by the child

him or herself, their behavioural inuence is weaker. However, even in this case, family norms are found to have a strong

inuence on child behaviour, of the same order of magnitude as the childs own attitude towards the behaviour. This lends

further support to Hypothesis 1.1. Also in this case, all normative inuences are mediated through the descriptive norm indi-

cator, the parents behaviour, thus conrming Hypothesis 1.2.

Again in the SEM analyses, we controlled for parental disagreement regarding the three behaviours. According to Tables 3

and 4, parental disagreement tends to reduce the childs inclination to save electricity whereas the two other behaviours

seem not to be affected after controlling for attitudes and norms.

4.3. Moderator analysis

As mentioned above, there is reason to expect that a range of family characteristics (and possibly other factors) moderate

the inuence of family norms on adolescents pro-environmental behaviour. We investigated the effects of two such poten-

tial moderators: the generation gap and the extent to which the parenting style in the family supports the childs

autonomy.

We used multigroup SEM for the moderator analyses. For this purpose, we created dichotomous grouping variables, split-

ting the sample at the mean of the autonomy support scale and at the mean age of the participating parents (since the ado-

Table 3

Structural models.

Electricity saving N = 601 Recycling N = 601 Buying green N = 405

Parent behaviour 0.36 0.05 0.11

Parent attitude 0.02 0.03 0.07

Child attitude 0.16

*

0.09

**

0.24

***

Perc. parent behaviour 0.87

**

0.90

***

0.83

***

Perc. parent attitude 0.37

*

0.08

*

0.09

Parent disagreement 0.14

*

0.02 0.04

R

2

0.32 0.72 .63

Note: Standardized solutions, only the structural models. The rest of the AMOS output can be acquired from the second author.

Fit indices: Electricity saving: Chisquare = 210.449, 48 d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 94; RMSEA = .075 (90% condence interval: .065.083). Recycling: Chi-

square = 122.421, 47 d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 99; RMSEA = .052 (90% condence interval: .041.063). Green buying: Chisquare = 100.218, 47 d.f., p < .001;

CFI = . 99; RMSEA = .053 (90% condence interval: .039.067).

*

p < .05,

**

p < .01,

***

p < .001.

298 A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302

lescents in the sample had roughly equal age). We then tted simplied versions of the above models to each subgroup,

including as predictors only the important predictor variables, that is, the childs attitude to the behaviour and the two

descriptive norms indicators (one at a time). In order to test whether differences between groups are statistically signicant,

a model where the structural paths (regression weights) are assumed to be identical between groups is compared to one

where they are allowed to vary.

The multigroup SEM analysis testing the possible moderation effect of the generation gap on the normative inuence of

parents rejected this hypothesis. When the regression weight for the norm factor is restricted to be equal between groups

dened by the size of the gap (large vs. small) the change in the overall t is not signicant for any of the three behaviours,

irrespective of whether parents self-reports or the childs perception of parents behaviour is used as the indicator for

descriptive norms in the family (Dv

2

electricity

= .022, 1 d.f., p = .88/.408, 1 d.f., p = .52, Dv

2

recyling

= 1.297, 1 d.f., p = .26/0.840, 1

d.f., p = .36, Dv

2

\green" buying

= .630, 1 d.f., p = .43/0.838, 1 d.f., p = .36).

The second multigroup SEM analysis, testing the possible moderation effect of an autonomy supportive parenting style on

the relative weight of the normative and attitudinal component did not fare better. When the regression weights are re-

stricted to be equal between groups dened by parenting style (low vs. high autonomy support) the change in the overall

t is not signicant for two of the three behaviours, irrespective of which of the two indicators for descriptive norms in

the family is used (Dv

2

electricity

= 3.518, 2 d.f., p = .17/.265, 1 d.f., p = .61, Dv

2

recyling

= .455, 2 d.f., p = .80/2.628, 2 d.f., p = .27,

Dv

2

\green" buying

= .197, 2 d.f., p = .90/8.264, 2 d.f., p < .05). Fixing the regression weights to be equal between groups signi-

cantly reduced the t of the model regarding green buying. However, the difference between the two groups is the oppo-

site of what we hypothesised. In the high autonomy support group, the standardized regression weights for descriptive

norm/attitude are .76/.10 and in the low autonomy support group they are .58/.24, suggesting a weaker inuence of the

childs own attitude, relative to family norms in the high than in the low autonomy support group. Since this result appeared

only in one of six calculations, it may be due to statistical chance and should not be over-interpreted. However, it is safe to

say that the moderation analyses did not support our hypotheses.

5. Discussion

Adolescents are mature enough to have their own opinions about many things, to do chores in the family and, in general,

to be held responsible for their everyday behaviour living up to certain standards. Reecting this, adolescents in our study

perform everyday pro-environmental behaviours to varying degrees, and the extent to which they do so depends on their

attitudes towards these activities. However, dominant family norms, as reected primarily in their parents behaviour, ex-

plain at least as much (and perhaps quite a bit more, depending on how it is measured) behavioural variance as the adoles-

cents own attitudes.

In principle, and also according to this study, the behavioural impact of descriptive family norms is mediated through the

childs perception of the parents behaviour. This also means that the normative inuence depends of the visibility and

(un)ambiguity of the parents behaviour. We found a higher impact of ambiguity and weaker effects overall with respect

to curtailing electricity use relative to the other two behaviours, which probably reects the fact that parents everyday elec-

tricity saving acts are less obtrusive than when they purchase organic and environment friendly products or source separate

their waste. In short, childrens inclination to act in a pro-environmental way appears to be highly inuenced by their par-

ents ditto actions and in particular by how the they perceive their parents behaviour. The latter also means that the effect of

childrens ingrained propensity to imitate their parents depends on how visible the parents behaviours are to the children.

It also seems likely, based on previous research, that parental inuence depends on a range of family characteristics, such

as the size of the generation gap and parenting style. However, in the present study we found parental inuence to be sta-

ble across families dened with reference to these two characteristics, which suggests that it is a quite robust factor in the

socialisation of children. On the other hand, families vary in many other ways, some of which may actually moderate the

relationships we report here.

Table 4

Structural models, reduced.

Electricity saving N = 601 Recycling N = 601 Buying green N = 405

Parent behaviour 0.21

***

0.37

***

0.43

***

Parent attitude 0.07 0.04 0.13

Child attitude 0.24

***

0.27

***

0.45

***

Parent disagreement 0.10

*

0.04 0.03

R

2

0.13 0.25 0.45

Note: Standardized solutions, only the structural models. The rest of the AMOS output can be acquired from the second author.

Fit indices: Electricity saving: Chisquare = 161.377, 28 d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 94; RMSEA = .089 (90% condence interval: .076.103). Recycling: Chi-

square = 47.316, 27 d.f., p < .01; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .035 (90% condence interval: .018.052). Green buying: Chisquare = 47.897, 27 d.f., p < .001; CFI = . 99;

RMSEA = .044 (90% condence interval: .022.064).

p < .01.

*

p < .05,

***

p < .001.

A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302 299

Parents attitudes towards the analysed pro-environmental behaviours, or family injunctive norms, are also positively

correlated with their childrens attitudes towards and performance of these behaviours. However, the inuence of family

injunctive norms disappears when controlling for descriptive norms. The nding that there is a much weaker correlation be-

tween the childs perception and the parents self-report with regard to the parents attitude than his or her behaviour sug-

gests that one of the reasons is the fact that children are more uncertain about their parents attitudes than about their

behaviour. The complete mediation of our measures of family injunctive norms through family descriptive norms further

suggests that children tend to infer the former from the latter, more salient and less ambiguous cue. This conrms the

old adage that it is what parents practice much more than what they preach that inuences childrens behaviour, and

is important for their socialisation.

Although parenting styles seem not to moderate these relationships, this does not mean that the parenting style is nec-

essarily unimportant for adolescents environmentally responsible behaviour. Additional analyses suggest that adolescents

are more likely to perform pro-environmental actions when they experience autonomy support in their family.

1

This is only a

caveat, however. Descriptive family norms as reected in their parents behaviour remain the most important predictor of ado-

lescents environmentally responsible behaviour across all three cases.

Hence, our study strongly suggests that parental inuence on their childrens propensity to act in favour of the environ-

ment is substantial and that parents are important role models for the transmission of pro-environmental practices to the

next generation. However, because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, the direction of causality cannot be settled

by this study. That is, in principle, the results may to a larger or smaller extent reect adolescents inuence on their

parents behaviour in a reverse or reciprocal socialisation process. However, based on the mounting evidence that adoles-

cents are usually less committed to pro-environmental practices than their parents (European Commission, 2008a,

2008b; Grnhj & Thgersen, 2009; Johnson et al., 2004) it seems more likely that family inuence within this behavioural

domain primarily runs from parent to child.

Another reservation to the ndings of the present study is the fact that parents and their children could be similarly inu-

enced as they are situated in identical socio-economic positions and physical locations. Hence, similarities in values and atti-

tudes could be a result of parents and children having gone through the same attitude-shaping experiences (Glass, Bengtson,

& Dunham, 1988). While this may be a plausible explanation for the similarity found in values and attitudes, it cannot ac-

count for the (much stronger) association between childrens and their parents (perceived) behaviour, however.

In terms of policy implications, the study suggests two avenues for encouraging environmentally responsible behaviour

in the young generation. First, the found signicant impact of young peoples attitudes on their environmentally responsible

behaviour supports efforts to target them directly, including for example, environmental education integrated into the cur-

riculum in schools and in higher education (e.g., Rickinson, 2001). In this connection, campaigners need to consider the

prominence of new media in young peoples lives and how content in these and other media related to sustainability issues

is interpreted, used and (inter)acted upon by the young generation (cf. Larsson, Andersson, & Osbeck, 2010). Second, the

strong impact of dominating family norms identied in this study suggests that this group might also, and perhaps more

effectively, be reached through their parents, and through making parents more aware of their role in fostering a sustainable

development, both directly and as role models. Hence, campaigns directed at parents may emphasize that they do function

as role models in this area, even for older children who may have got other points of (socialisation) reference as well. Among

other things, based on the stronger inuence of parents actions relative to their attitudes, parents should be advised to make

their pro-environmental behaviour visible to their children.

An area of unsustainable consumption by many households that pose special challenges according to this study is elec-

tricity use based on non-renewable resources. The fundamental problem is that households use of electricity is largely invis-

ible (Darby, 2000), which makes parental teaching by modelling a challenge. This was, among other things, reected in the

weak correlation between parents and adolescents electricity curtailment behaviour found in this study. However, recent

research suggests that technological feedback devices that visualise real-time use of energy by households can help over-

come this problem and thereby support childrens (and parents) learning processes related to energy conservation (Grnhj

& Thgersen, 2011). The support of family learning and socialisation processes may be one of the most important advantages

of the many new smart visualisation technologies that are being tested and introduced by electricity companies in, espe-

cially, Europe and North America these years.

As a nal remark, we want to emphasize the obvious implication of this study that we cannot push the responsibility for

creating a sustainable future to the next generation. Parental, and not least governmental, leadership is needed, not only to

prepare, but also to show the way.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Danish National Research Agency (FSE) (Grant No. 24-02-0305).

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

1

These calculations can be acquired from the authors.

300 A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302

Antonides, G., & van Raaij, W. F. (1998). Consumer behaviour. A European perspective. Chicester, Wiley.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). Amos 7.0 users guide. Chicago: SPSS.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1994). Structural equation models in marketing research: Basic principles Principles of marketing research (pp. 317385). Cambridge: Blackwell

Publishers.

Baker, C. W., Little, T. D., & Brownell, K. D. (2003). Predicting adolescent eating and activity behaviors: The role of social norms and personal agency. Health

Psychology, 22, 189.

Baker, C. W., Whisman, M. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2000). Studying intergenerational transmission of eating attitudes and behaviors: Methodological and

conceptual questions. Health Psychology, 19, 376.

Ballantyne, R., Fien, J., & Packer, J. (2001). Program effectiveness in facilitating intergenerational inuence in environmental education: Lessons from the

eld. Journal of Environmental Education, 32(4), 815.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Baslington, H. (2008). Travel socialization: A social theory of travel mode behavior. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 2, 91114.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4, 1103.

Biel, A., & Thgersen, J. (2007). Activation of social norms in social dilemmas: A review of the evidence and reections on the implications for environmental

behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28, 93112.

Blackwell, R. D., Miniard, P. W., & Engel, J. F. (2006). Consumer behavior. Portland: Thomson/South-Western.

Carlo, G., McGinley, M., Hayes, R., Batenhorst, C., & Wilkinson, J. (2007). Parenting styles or practices? Parenting, sympathy, and prosocial behaviors among

adolescents. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168, 147176. Taylor & Francis Ltd..

Carlson, L., & Grossbart, S. (1988). Parental style and consumer socialization of children. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 7494.

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social inuence. Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591621.

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical renement and re-evaluation. Advances in Experimental

Social Psychology, 24, 201234.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 10151026.

Danmarks_Statistik (2009). Nyt fra Danmarks Statistik. Befolkning og valg. Indvandrere i Danmark 2009. Kbenhavn.

Darby, S. (2000). Making it obvious: Designing feedback into energy consumption. In: P. Bertoldi, A. Ricci, & D. A. A. (Eds.), Energy efciency in household

appliances and lighting (pp. 685696). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory. Perceptions of parents scales (POPS). <http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/measures/

pops_collegestudentscale.php> Accessed 06.10.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Sonkovics, R. R., & Bohlen, G. M. (2003). Can socio-demographics still play a role in proling green consumers? A

review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research, 56, 465480.

Easterling, D., Miller, S., & Weinberger, N. (1995). Environmental consumerism: A process of childrens socialization and families resocialization. Psychology

and Marketing, 12, 531550.

Ekstrm, K. M. (1995). Childrens inuence in family decision making. Department of Business Administration, Gteborg, Gteborg University (411).

Ekstrm, K. M. (1999). Barns pverkan p frldrar i ett engagemangskrvende konsumptionssamhlle. In K. M. Ekstrm & H. Forsberg (Eds.), Den

erdimensionella konsumenten En antalogi om svenska konsumenter. Gteborg: Tre Bcker Forlag AB.

European Commission (2008a). Europeans attitudes towards climate change, Special Eurobarometer300/69.2. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2008b). Attitudes of European citizens towards the environment, Special Eurobarometer 295/EB 68.2. Brussels: European Commission.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117140.

Gagn, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 199223.

Glass, J., Bengtson, V. L., & Dunham, C. C. (1988). Attitude similarity in three-generation families: Socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal inuence.

American Sociological Review, 51, 685698.

Gckeritz, S., Schultz, P. W., Rendn, T., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2010). Descriptive normative beliefs and conservation behavior: The

moderating roles of personal involvement and injunctive normative beliefs. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 514523.

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels.

Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 472481.

Gotschi, E., Vogel, S., & Lindenthal, T. (2010). The role of knowledge, social norms, and attitudes toward organic products and shopping behavior: Survey

results from high school students in Vienna. Journal of Environmental Education, 41(2), 88101.

Grodzinska-Jurczak, M., Bartosiewicz, A., Twardowska, A., & Ballantyne, R. (2003). Evaluating the impact of a school waste education programme upon

students, parents and teachers environmental knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. International Research in Geographical & Environmental Education,

12(2), 106122.

Grolnick, W. S., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1997). Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective. In J. E. Grusec & L. Kuczynski

(Eds.), Parenting and childrens internalization of values. A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 135161). New York: Wiley.

Grusec, J. E., & Kuczynski, L. (Eds.). (1997). Parenting and childerns internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory. New York: Wiley.

Grnhj, A. (2007). Green girls and bored boys? Adolescents environmental consumer socialization. In B. Tufte & K. Ekstrm (Eds.), Children, media &

consumption (pp. 319333). Gteborg: Nordicom.

Grnhj, A., & Thgersen, J. (2009). Like father, like son? Intergenerational transmission of values, attitudes and behaviors in the environmental domain.

Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 414421.

Grnhj, A., & Thgersen, J. (2011). Feedback on household electricity consumption: Learning and social inuence processes. International Journal of

Consumer Studies, 35(2), 138145.

Haustein, S., & Hunecke, M. (2007). Reduced use of environmentally friendly modes of transportation caused by perceived mobility necessities: An

extension of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 18561883.

Hsieh, Y.-C., Chiu, H.-C., & Lin, C.-C. (2006). Family communication and parental inuence on childrens brand attitudes. Journal of Business Research, 59,

10791086.

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-ve years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26,

183213.

Johnson, C. Y., Bowker, J. M., & Cordell, H. K. (2004). Ethnic variation in environmental belief and behavior: An examination of the new ecological paradigm

in a social psychological context. Environment and Behavior, 36, 157186.

Kallgren, C. A., Reno, R. R., & Cialdini, R. B. (2000). A focus theory of normative conduct: When norms do and do not affect behavior. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 26, 10021012.

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Zax, M., & Sameroff, A. J. (1995). The relations of maternal and social environments to late adolescents. Materialistic and Prosocial

Values, 31(6), 907914.

Kuczynski, L., & Parkin, M. C. (2006). Agency and bidirectionality in socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and

research (pp. 259283). New York: Guilford.

Larsson, B., Andersson, M., & Osbeck, C. (2010). Bringing environmentalism home. Childrens inuence on family consumption in the Nordic countries and

beyond. Childhood, 17(1), 129147.

Maccoby, E. E. (2006). Historical overview of socialization research and theory. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and

research (pp. 1341). New York: Guilford.

A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302 301

Mandrik, C. A., Fern, E. F., & Bao, Y. (2005). Intergenerational inuence. Roles of conformity to peers and communication effectiveness. Psychology and

Marketing, 22, 813832.

Mangleburg, T. F., & Bristol, T. (1998). Socialization and adolescents skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising, 27(3), 1121.

Moore, E. S., & Wilkie, W. L. (2005). We are who we were. Intergenerational inuences in consumer behavior. In S. Ratneshwar, & D. G. Mick (Eds.), Inside

consumption. Consumer motives, goals and desires (pp. 208232). New York: Routledge.

Moore, E. S., Wilkie, W. L., & Alder, J. A. (2001). Lighting the torch: How do intergenerational inuences develop? Advances in Consumer Research, 28,

287293.

Moore, E. S., Wilkie, W. L., & Lutz, R. J. (2002). Passing the torch: Intergenerational inuences as a source of brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 66(2), 1737.

Moore-Shay, E. S., & Lutz, R. J. (1988). Intergenerational inuences in the formation of consumer attitudes and beliefs about the marketplace. Mothers and

daughters. Advances in Consumer Research, 15, 461467.

Moschis, G. P. (1985). The role of family communication in consumer socialization of children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 11, 898913.

Moschis, G. P. (1987). Family inuences. Consumer socialization: A life-cycle perspective. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Moschis, G., & Moore, R. (1982). A longitudinal study of television advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 279286.

Musick, K., Seltzer, J. A., & Schwartz, C. R. (2008). Neighborhood norms and substance use among teens. Social Science Research, 37, 138155.

Nolan, J. M., Schultz, P. W., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). Normative social inuence is underdetected. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 34, 913923.

Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. R. (2000). On the origin and distinctness of skepticism toward advertising. Marketing Letters, 11, 311322.

OECD (2002). Towards sustainable household consumption? Trends and policies in OECD countries. OECD: Paris.

Olsen, B. (1993). Brand loyalty and lineage: Exploring new dimensions for research. Advances in Consumer Research, 20, 276284.

Park, W. (1977). Students and housewives Differences in susceptibility to reference group inuence. Journal of Consumer Research, 4, 102111.

Rickinson, M. (2001). Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research, 7, 207320.

Schultz, P. W. (1999). Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: A eld experiment of curbside recycling. Basic and Applied Social

Psychology, 21, 2536.

Thgersen, J. (2008). Social norms and cooperation in real-life social dilemmas. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 458472.

Ward, S. (1974). Consumer socialization. Journal of Consumer Research, 1, 114.

Whitbeck, L. B., & Gecas, V. (1988). Value attributions and value transmission between parents and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 829840.

Wood, M. D., Read, J. P., Mitchell, R. E., & Brand, N. H. (2004). Do parents still matter? Parent and peer inuences on alcohol involvement among recent high

school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 1930.

Wray-Lake, L., Flanagan Constance, A., & Osgood, D. W. (2010). Examining trends in adolescent environmental attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors across three

decades. Environment and Behavior, 42, 6185.

Youn, S. (2008). Parental inuence and teens attitude toward online privacy protection. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 42, 362388.

302 A. Grnhj, J. Thgersen/ Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 292302

You might also like

- A Rooms (1603-1856) B Rooms (1903-2156) C Rooms (2203-2456) D Rooms (2503-2756) E Rooms (2803-3056)Document1 pageA Rooms (1603-1856) B Rooms (1903-2156) C Rooms (2203-2456) D Rooms (2503-2756) E Rooms (2803-3056)Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- FINA synchronised swimming rules guide 2013-2017Document70 pagesFINA synchronised swimming rules guide 2013-2017Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- CT MMB 073Document2 pagesCT MMB 073Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0272735813001566 MainDocument19 pages1 s2.0 S0272735813001566 MainBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Perspectives On Diagnostic Systems: Denny BorsboomDocument20 pagesPsychometric Perspectives On Diagnostic Systems: Denny BorsboomBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- The Habitus Process A Biopsychosocial Conception: Andreas PickelDocument36 pagesThe Habitus Process A Biopsychosocial Conception: Andreas PickelBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0272735813001566 MainDocument19 pages1 s2.0 S0272735813001566 MainBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Beg Swimming TechniqueDocument17 pagesBeg Swimming Techniquevirpara100% (1)

- NHS Choices - Delivering For The NHSDocument24 pagesNHS Choices - Delivering For The NHSJames BarracloughNo ratings yet

- The Habitus Process A Biopsychosocial Conception: Andreas PickelDocument36 pagesThe Habitus Process A Biopsychosocial Conception: Andreas PickelBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Batson & Ahmad (In Press)Document65 pagesBatson & Ahmad (In Press)Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- Eco Anthro 22Document110 pagesEco Anthro 22Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- Short AQAL Beyond The Biopsychosocial ModelDocument16 pagesShort AQAL Beyond The Biopsychosocial ModelBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0272494409000486 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0272494409000486 MainBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology: Five Classes of Research Questions in Clinical PsychologyDocument12 pagesClinical Psychology: Five Classes of Research Questions in Clinical PsychologycarlammartinsNo ratings yet

- Chandola 2008 Unhealthy Behaviours Stress and CHDDocument9 pagesChandola 2008 Unhealthy Behaviours Stress and CHDBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Essaywriting 131213020540 Phpapp01Document5 pagesEssaywriting 131213020540 Phpapp01api-235870670No ratings yet

- Cohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseDocument3 pagesCohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Chronic Illness 2011 Michalak 209 24Document17 pagesChronic Illness 2011 Michalak 209 24Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- Positive Psychologists On Positive Psychology: Ilona BoniwellDocument6 pagesPositive Psychologists On Positive Psychology: Ilona BoniwellBilly Cooper100% (1)

- Positive Psychologists On Positive Psychology: Ilona BoniwellDocument6 pagesPositive Psychologists On Positive Psychology: Ilona BoniwellBilly Cooper100% (1)

- Tips for writing a critical essayDocument2 pagesTips for writing a critical essayBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Aging: PsychologistsDocument8 pagesPsychology and Aging: PsychologistsThamer SamhaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Approach To Successful Ageing Predicts Future Quality of Life in Older AdultsDocument10 pagesPsychological Approach To Successful Ageing Predicts Future Quality of Life in Older AdultsBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Mac BrushDocument1 pageMac BrushBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- 10 Minute Trainer Accelerated Schedule1Document1 page10 Minute Trainer Accelerated Schedule1Billy CooperNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0005796711000234 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0005796711000234 MainBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Marine Policy: M Alejandra Koeneke Hoenicka, Sara Andreotti, Humberto Carvajal-Chitty, Conrad A. MattheeDocument8 pagesMarine Policy: M Alejandra Koeneke Hoenicka, Sara Andreotti, Humberto Carvajal-Chitty, Conrad A. MattheeAlejandra SwanNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Information Technology, Digital Transformation, and Job Satisfaction On Employee Performance in Regional Office The National Land AgencyDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Information Technology, Digital Transformation, and Job Satisfaction On Employee Performance in Regional Office The National Land AgencyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- (IEEE PCS Professional Engineering Communication Series) Catherine G.P. Berdanier, Joshua B. Lenart - So, You Have To Write A Literature Review - A Guided Workbook For Engineers-Wiley-IEEE (2020)Document143 pages(IEEE PCS Professional Engineering Communication Series) Catherine G.P. Berdanier, Joshua B. Lenart - So, You Have To Write A Literature Review - A Guided Workbook For Engineers-Wiley-IEEE (2020)MaimunaBegumKaliNo ratings yet

- Adinan Sufiyan, Individual Assignment of Mini-Research Community and Development PsychologyDocument37 pagesAdinan Sufiyan, Individual Assignment of Mini-Research Community and Development PsychologyDukkana BariisaaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human Behaviour and Crew Resource ManagementDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Human Behaviour and Crew Resource ManagementBirender TamsoyNo ratings yet

- Course Material Part-2Document224 pagesCourse Material Part-2pranav_joshi_32No ratings yet

- Learners Critical Thinking About Learning Mathematics 11003Document18 pagesLearners Critical Thinking About Learning Mathematics 11003Annisa RNo ratings yet

- Advances in Consumer Research - White Paper CollectionDocument94 pagesAdvances in Consumer Research - White Paper Collectionglen_durrantNo ratings yet

- Business Research Chapter 1Document8 pagesBusiness Research Chapter 1Algie MAy Gabriel Aguid-GapolNo ratings yet

- (Full Text) Hemenway, D., King, FJ., Rohani, F., Word, J., & Brennan, M. (2003)Document94 pages(Full Text) Hemenway, D., King, FJ., Rohani, F., Word, J., & Brennan, M. (2003)Felipe SepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- DisentanglementDocument6 pagesDisentanglementHeather ArmstrongNo ratings yet

- Psychological Report WritingDocument5 pagesPsychological Report WritingSteffi PerillaNo ratings yet

- Logan, Et Al. (2012) Advertising ValueDocument16 pagesLogan, Et Al. (2012) Advertising ValueSiswoyo Ari WijayaNo ratings yet

- HRM627 Final Term 2010 S01Document102 pagesHRM627 Final Term 2010 S01tina kaifNo ratings yet

- Gagnes Theory of Learning: They Include Concepts, Rules and ProceduresDocument11 pagesGagnes Theory of Learning: They Include Concepts, Rules and Proceduresmaddy mahiNo ratings yet

- Science and Health Com CollegeDocument14 pagesScience and Health Com CollegeJeyyNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and AttitudesDocument16 pagesJob Satisfaction and AttitudesPaupauNo ratings yet

- DLP Week 1.1Document9 pagesDLP Week 1.1Shiela Castardo EjurangoNo ratings yet

- Fmls Module 1Document20 pagesFmls Module 1anitta2024No ratings yet

- Metaphorical Expressions and Culture An Indirect LinkDocument18 pagesMetaphorical Expressions and Culture An Indirect LinkSundy LiNo ratings yet

- (Amaleaks - Blogspot.com) Oral Communication Grade 11 Week 11-20Document27 pages(Amaleaks - Blogspot.com) Oral Communication Grade 11 Week 11-20jade rhey100% (2)

- Presentation 7912 Change MGMTDocument22 pagesPresentation 7912 Change MGMTSunNo ratings yet

- Values Education Approaches PDFDocument9 pagesValues Education Approaches PDFkaskarait100% (1)

- Effective Technical Communication PDFDocument3 pagesEffective Technical Communication PDFSANDEEP PatelNo ratings yet

- TETVI-RESEARCH EditedDocument11 pagesTETVI-RESEARCH EditedPsalms Aubrey Domingo AcostaNo ratings yet

- The Ironic Filipino Humor: Culture of Anti-Intellectualism On The Self-Esteem of Grade 12 Academic Achievers at Lyceum of Alabang, S.Y. 2022-2023Document16 pagesThe Ironic Filipino Humor: Culture of Anti-Intellectualism On The Self-Esteem of Grade 12 Academic Achievers at Lyceum of Alabang, S.Y. 2022-2023Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal100% (1)

- EDU402 MidtermpastpapersanddataDocument36 pagesEDU402 Midtermpastpapersanddatasara ahmadNo ratings yet

- Fatuma NuruDocument12 pagesFatuma NuruFatuma NuruNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Ramanuj MajumdarDocument408 pagesConsumer Behaviour Ramanuj MajumdarlubnahlNo ratings yet

- The Evaluative Psychiatric ReportDocument12 pagesThe Evaluative Psychiatric ReportJuanCarlos Yogi100% (1)