Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Studiu Calitstudiu Calitativ in Recuperarea Medicala

Uploaded by

Alexandra Nadinne0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views9 pagesStudiu calitstudiu calitativ in recuperarea medicala

Original Title

Studiu calitstudiu calitativ in recuperarea medicala

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentStudiu calitstudiu calitativ in recuperarea medicala

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views9 pagesStudiu Calitstudiu Calitativ in Recuperarea Medicala

Uploaded by

Alexandra NadinneStudiu calitstudiu calitativ in recuperarea medicala

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162

Patients perspectives of patient-centredness as important in

musculoskeletal physiotherapy interactions: a qualitative study

Martin O. Kidd

a,

, Carol H. Bond

b

, Melanie L. Bell

c

a

School of Physiotherapy, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand

b

Student Learning Centre, University of Otago, New Zealand

c

Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, New Zealand

Abstract

Objective To determine patients perspectives of components of patient-centred physiotherapy and its essential elements.

Design Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews to explore patients judgements of patient-centred physiotherapy. Grounded theory

was used to determine common themes among the interviews and develop theory iteratively from the data.

Setting Musculoskeletal outpatient physiotherapy at a provincial city hospital.

Participants Eight individuals who had recently received physiotherapy.

Results Five categories of characteristics relating to patient-centred physiotherapy were generated from the data: the ability to communicate;

condence; knowledge and professionalism; an understanding of people and an ability to relate; and transparency of progress and outcome.

These categories did not tend to occur in isolation, but formed a composite picture of patient-centred physiotherapy from the patients

perspective.

Conclusions and practice implications This research elucidates and reinforces the importance of patient-centredness in physiotherapy, and

suggests that patients may be the best judges of the affective, non-technical aspects of a given healthcare episode.

2010 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Patient care; Patient centredness; Patient satisfaction; Good physiotherapy

Introduction

Calls for those involved in the health professions to seek

patients viewpoints regarding their care (or level of satisfac-

tion) have been evident in various forms in the literature for

over 40 years [14]. However, interpretation of a patients

view has varied signicantly depending upon the model

of patient satisfaction upon which studies are based [57].

Research on patient satisfaction, as measured by self-report,

has expanded signicantly in virtually all healthcare spe-

cialties [8]. In 1997, Sitzia and Wood reported a peak of

over 1000 published articles using the term patient satis-

faction [1]. For example, Nelson identied ve domains

of patient satisfaction that focused on access, administra-

tive technical management, clinical technical management,

Corresponding author. Tel.: +64 34798436; fax: +64 34798414.

E-mail address: martin.kidd@otago.ac.nz (M.O. Kidd).

interpersonal management and continuity of care [9]. In phys-

iotherapy, studies of patient satisfaction have been few and,

until recently, were predominantly quantitative and question-

naire based [1012].

Patient satisfaction with physiotherapy can be inu-

enced by an interaction between therapist and patient that

may involve more physical contact and active involvement

of the patient than encounters with other health profes-

sionals [11]. Therefore, it is suggested that physiotherapy

patients perceptions require a different interpretation [10],

as well as a different measurement tool from other health

professions [11]. Accordingly, in physiotherapy research,

profession-specic satisfaction variables more applicable

to physiotherapy settings have been used: time with the

patient; therapist behaviour; physical security; consistency

and logical progression; and the adaptation of the treat-

ment programme to the patients problem based on input

from physiotherapy professionals [10,11]. In most of the

0031-9406/$ see front matter 2010 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.physio.2010.08.002

M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162 155

physiotherapy satisfaction studies, satisfaction with specic

encounters has been determined using researcher-derived,

patient self-report instruments, which are framed in terms of

institutional or professional perspectives rather than those of

the patient. Therefore, and despite possible intentions to the

contrary, satisfaction research has typically reected some of

the attitudes and values of an earlier biomedical model rather

than a contemporary patient-centred perspective. In research

that purports to seek patients views of what is important to

them in physiotherapy, such a position is incongruous.

Patient-centred care

In the patient-centred care model, the healthcare episode

is an equal partnership between clinician and patient [13].

According to Stewart [14, p. 444], patient-centredness in

medicine may be most commonly understood for what it is

not: technology centred, doctor centred, hospital centred,

disease centred (consultation model). Similarly, Cott [15,

p. 89] suggests that there is no common denition of client-

centred rehabilitation, stating that most available denitions

focus on acute care from the perspectives of various health

professionals rather thanthe clients. The patient-centredcare

model locates the patient centrally in the professional rela-

tionship, and supports the notion that an understanding of

the patients perspective should underpin good practice in an

equal therapeutic relationship (Fig. 1).

Implications for research

The aim of this research programme was to develop a

patient self-report instrument to be used in the assessment of

physiotherapists clinical performance inthe musculoskeletal

area. The two-stage process began with generation of quali-

tative data from patients about what is important to them in

encounters with their physiotherapist. With an understanding

of patients perspectives of the patient-centredcare model, the

data could be used in the development and testing of an instru-

ment to measure whether clinicians match those perspectives.

This article reports on the rst stage.

The few studies that have sought patients views about

what theyvalue ina therapeutic encounter are scatteredacross

professions, disciplines and services, and use a range of meth-

ods [2,1620]. A recurring theme that emerges from these

studies is the value that patients place on clinicians com-

munication with the patient (in terms of listening, explaining

and instructing). However, is there more to patient-centred

physiotherapy than the ability to communicate? Rohrer et al.

[21] suggest that self-rated health is more related to empow-

erment than satisfaction with communication. Stewart argued

that patient centredness is an important area of study, and is

best dened and assessed by the patients themselves [14].

The researchers in this study want to inform clinicians about

which patient values may be at the centre of clinical interac-

tions in a patient-centred care context.

Method

Design

Audio-taped semi-structured interviews in conjunction

with grounded theory were used to study patients per-

spectives of patient-centred physiotherapy. The interviews

Traditional consultation

model

Patient-centred care

model

CLINICIAN

CLINICIAN

Disease Hierarchical

Biomedical

Unidirectional

Therapeutic

alliance

Biopsychosocial

Two-directional

Illness

PATIENT

(active partner)

PATIENT

(passive recipient)

Fig. 1. Comparison of the patient-centred care model with the traditional consultation model.

156 M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162

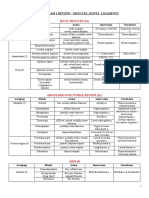

Table 1

Characteristics of the sample (n =8).

Study number Occupation Age

(years)

Gender Ethnicity

1 Tertiary student 20 Male Asian

2 Government

administrator

52 Female Caucasian

3 Night worker at

warehouse

61 Male Caucasian

4 Maintenance

engineer

56 Male Caucasian

5 Retired priest 65 Female Caucasian

6 Retired 68 Male Maori

a

7 Medical service

manager

52 Female Caucasian

8 Home maker 40 Female Maori

a

The indigenous people of New Zealand.

occurred at the participants place of work (n =2), at their

home (n =1) or at the researchers workplace (n =5). Patients

were asked how they judged the treatment they received

to determine which components of physiotherapy they per-

ceived as important to them. The last question was: In

general, what is good physiotherapy? Each main question

was explored using neutral probes such as Can you tell me

more?, What are the most important aspects. . .? and What

do you mean by? to deepen participants responses and

explore topics further [22,23]. Interviews were recorded and

transcribed verbatim and participants were given a number.

Ethical approval was gained from the Lower South Regional

Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained prior to

participation in the research.

Participants

A purposive sample of eight patients was recruited from

the local hospital physiotherapy outpatients department by a

process that preserved physiotherapist anonymity. The sam-

ple (see Table 1) resembled the prole of patients who

typically attended the department.

A musculoskeletal outpatient population was selected

because their clinical events have comparatively short

treatment timeframes compared with other physiotherapy

contexts, because of ease of interview scheduling, and

because these patients were likely to meet the inclusion cri-

teria [24] (Table 2). These criteria ensured a sample with

sufcient physiotherapy experience while minimising the

possibility of comorbidities and dependence resulting in

biased views. The 10-session limit was rationalised through

New Zealands Accident Compensation Corporation policy

[25]. The Accident CompensationCorporationis a no-faults

government-owned medical insurance scheme which cov-

ers most accident-related rehabilitation, and stipulates that

10 typically represents the maximum number of treatments

which leads to a satisfactory outcome for a patient receiving

musculoskeletal physiotherapy care.

Analysis

Grounded theory is a useful qualitative method if little

is known about a topic and few theories exist to explain or

predict a groups behaviour [26]. Grounded theory allows

research results to be grounded in the social world of the

people being studied, while comprising a systematic and

structured set of procedures to induce theory [27] about

a phenomenon from the data (i.e. patients perspectives of

patient-centred physiotherapy).

The main study sample of eight patients was determined

according to the grounded theory concept of theoretical sat-

uration [28], which describes when conceptual explanations

arising from analysis of the data are well developed, and

no new themes emerge from ongoing data collection. Data

generation was followed by data analysis for each individual

interview (Fig. 2).

Each transcript was read several times to sensitise to

the meanings ascribed to physiotherapy. A constant com-

parative analysis [24] was used in data analysis (Table 2).

Data management software (NVivo, QSR, International Pty

Ltd., Victoria, Australia) was used to store and manage the

data.

Coded passages were subjected to continued compari-

son and differentiation. Similar concepts were clustered to

form categories [24,29]. Categories were continually rened

and organised as new data emerged. Criteria for each code

were developed and noted as coding proceeded. For veri-

cation purposes, summaries of each transcript including

context, main themes, impressions and exemplary quotations

were prepared, and compared with memos written during the

interviews. Each summary represented perceptions of impor-

tant aspects of physiotherapy for that particular participant.

Next, axial coding [30] was applied to concepts within cat-

egories and across categories. This nal coding involved the

identication and comparison of inter-relationships between

the key properties of each category and consequential

theory building [31]. It was used to construct the core

category [24, p. 172] or central phenomenon [32, p.

1095]: the theory of patients perspectives of patient-centred

physiotherapy.

Results

Five categories of patients perspectives of patient-centred

physiotherapy were generated from the data (Table 2). Each

category is described in two parts: the contributing con-

cepts (derived from open coding), and within-category and

cross-category relationships (derived from axial coding)

(Fig. 3).

Ability to communicate

A primary nding, supported by previous literature, was

the importance of the abilitytocommunicate. Patients dened

M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162 157

Table 2

Patients views of the characteristics of a good physical therapist.

Characteristics of a good

physical therapist

Subcategories Exemplary passages No. of passages No. of participants

contributing to

nodes (n =8)

Clear communication Good listening skills theyve got to have good listening skills 4 3

Instructions about

self-help/exercise

she was a really good explainer; she

gave you alternatives

55 5

Reassurance about pain I hadnt realised that it was OK for it to

be painful

6 1

Condence Knowledge/skills/expertise [they] know what theyre talking about;

she was obviously spot-on;

15 7

Attitudes someone who knows what theyre

doing

6 4

Ability to create condence theyve got to come across as

condent; I just felt condence in her

11 3

The nature of the professional

relationship

Space for patient to suggest

treatment

I really felt that [it] was more to do with

the muscles on [my] spine

12 3

Patient leaves it to the physical

therapist

theyve got the training, I havent; I

left everything in the hands of the physio

13 4

An understanding of people

and an ability to relate

Empathetic a certain amount of empathy; an

understanding of the pain

5 3

Encouraging the way I was encouraged; they were

very encouraging

10 2

Ability to relate to patients and be

friendly

good people person; relaxed and . . .

easy to talk to; friendly . . . I could ask

her questions

27 4

A concern with progress and

outcome

Focus on progress you can see youre improving 13 5

Use of measurement each time . . . they re-measured it 13 3

Quick outcome my hand healed real quickly 6 2

this as a two-way transfer of information that both informs

and reassures the patient: good listening skills, paraphrasing

and explaining, and reassurance about pain were all evident

as components of that denition:

theyve got to listen to what youre saying (Participant 2,

52-year-old female)

Furthermore, it was considered important that physiother-

apists be able to interpret the lay speech of the patient:

we dont know the terminology to use . . . weve just to say

. . . its here and when I do this, this happens (Participant 4,

56-year-old male)

Patients appreciated the correct interpretation being

relayed back to them in a way they understood:

she listened to what I had to say, then explained things back

to me in a manner that . . . was easy to follow (Participant 6,

68-year-old male)

Interview 1

Analysis of Transcript

1 informs Interview 2

Interview 2

Interview 3

Analysis of Transcript

2 informs Interview 3

Analysis of Interview 3

informs Interview 4 etc.

Fig. 2. Process of data generation.

158 M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162

Good

listening

skills

Therapists

self-

confidence

Reassurance,

especially

about pain

Clear explanations

and instructions

Input into the treatment

plan and decisions about

treatment

Putting the patient at

ease

Empathy,

encouragement

and friendliness

Therapist creates a

relationship with

patient

Encouragement

knowledge of

progress motivates

engagement in

clinical process

Attitude to

patient and

treatment

Using strategies to

show change and

improvement

TRANSPARENT

FOCUS ON

PROGRESS AND

OUTCOMES

KNOWLEDGE

AND EXPERTISE

ABILITY TO

COMMUNICATE

Creates

understanding

UNDERSTANDING

PEOPLE AND

ABLE TO RELATE

CONFIDENCE

Understanding

pain

Creates patients

confidence in

therapist and

process

Fig. 3. Patients views of good physiotherapy: categories and inter-relationships. Boxes represent core categories, bold lines represent in-category relationships;

dotted box is an inferred concept.

Therefore, the quality of the therapists explanations

directly related to the patients understanding and reassur-

ance, and how they managed their condition:

. . .telling you . . . what was happening . . . what you can and

cant do . . . they just reassure you that youre doing the right

thing (Participant 4, 56-year-old male)

It was important to the patient to be reassured about pain,

and that it was alright to feel pain:

. . .the physiotherapist said to me . . .do it to where it gets

painful and just push it a bit but. . . the importance of doing

those passive exercises was really stressed to me and it just

made me realise how important it was to make sure that I

maintained movement in that armeven though it was painful

(Participant 5, 65-year-old female)

Condence

Some participants required a therapist who was condent

in explanations and attitude. For example, physiotherapists

should:

. . .know what theyre talking about . . .[and be] condent

about what theyre saying. . . (Participant 1, 20-year-old

male)

One participant:

. . .felt very condent that there was somebody there that

knewwhat she was doing (Participant 5, 65-year-old female)

and another stated that:

just working on the thing and not rushing it, explaining what

she was doing. . .what she was doing made sense to me . . . I

just felt condent (Participant 4, 56-year-old male)

Across categories, the therapists ability to communicate,

their use of their knowledge and expertise (see below), their

self-condence, and their ability to create condence in the

patient showa complex interdependent category relationship.

The patient needed to feel condent in the physiotherapist,

dependent on evidence of the physiotherapists own self-

condence and abilities:

. . .I had condence in [her] because when I . . . asked

anything I got good, clear answers. . . . Its the ability to

inspire condence, because youre not going to do the exer-

cises if you dont believe it (Participant 4, 56-year-old

male)

Knowledge, expertise and professionalism

Knowledge and expertise were considered to be essential

elements of good physiotherapy. One participant described

expertise as:

M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162 159

. . .she knew what she was doing. She knew those were the

right exercises, . . . and how I should do them and what it was

for . . . and I experienced the benet of them. . .. The way I

was treated, the way I was encouraged. The expertise. I felt

condent that the best thing was happening (Participant 5,

65-year-old female)

Knowledge and expertise were linked with patients views

of a professional relationship, and how, for example, the

therapist introduced herself:

They treated you very well. . .. There are a whole lot of

things that go [with professionalism]. Like just in the way

they . . . introduce themselves . . . ask you what the prob-

lem is. . . go through what youve done. . . (Participant 7,

52-year-old female)

Patients perspectives of patient-centred physiotherapy

involve a professional relationship that allowed space for the

patient to recognise the therapists knowledge, and to have

input into the treatment plan and decisions about treatment.

For example, although one participant may have thought

another treatment option would help him:

If I had a [therapist who] . . . manipulated or massaged me

neck and back and shoulder muscles more vigorously . . . that

would have xed it quicker or better (Participant 6, 68-year-

old male)

these sentiments were not usually communicated because the

therapist was perceived as having the training:

theyve got the training, I havent . . . I left everything in the

hands of the physio because I dont know what . . . goes on

in your shoulder (Participant 3, 61-year-old male)

Understanding people and an ability to relate

Patients considered it important that the physiotherapist

demonstrate empathy (especially in relation to pain), encour-

agement, and the ability to relate to people and be friendly:

[what matters is] a certain amount of empathy, an under-

standing of the pain, and a feeling that I matter and that Im

a real person (Participant 5, 65-year-old female)

and that the physiotherapist should be:

able to relate to patients . . . to put them at ease (Participant

6, 68-year-old male)

Patients insisted that the physiotherapist should locate the

patient at the centre of the therapeutic encounter, and make

them feel understood and respected:

they made you feel as though youre OK (Participant 4,

56-year-old male)

they were both very friendly. . . .youre number one for the

day, they made you feel important . . . like a real person that

they cared about (Participant 2, 52-year-old female)

Transparency of progress and outcome

Transparency of progress was important to the partici-

pants, especially by way of measurement. A physiotherapist

should communicate progress with the patient, who could

then condently comply with the programme. For example:

I had progressed to a stage where I could actually go off the

passive movement and get more involved in active lifting . . .

She tested my armto see at what point it was most painful and

then gave me exercises that seemed to relate to . . . improving

that pain (Participant 7, 52-year-old female)

She would tell me the progress that I was making. Like . . .

how far I could bend my nger . . . one week Id bend it 20

degrees . . . but the week after Id bend it 40 degrees. . . . She

just told me . . . how well I was going and shed say oh thats

such an improvement (Participant 1, 20-year-old male)

Positive outcomes were also emphasised. For some

patients, the progress was muchquicker thantheyanticipated:

My hand healed much quicker than expected by the doctor

. . . quicker than she thought it was going to be (Participant

1, 20-year-old male)

I got a really quick outcome here and I was really surprised

(Participant 2, 52-year-old female)

Positive outcomes were desirable, especially when

improvement was communicated and measurable:

. . .it will help the patient if he . . . knows that he . . . is improv-

ing. [You] work better or try harder to get better (Participant

1, 20-year-old male)

they made me feel as if I was doing really well. . . that I

was making progress . . . it was good to have that reinforced

by a professional . . . it encourages you to keep doing it

(Participant 7, 52-year-old female)

the [therapist] . . . was interested in my improvement week

by week and even went back through the records to say look

. . . back 3 or 4 weeks ago you were only getting this . . .they

told me what it was last time and what the difference was

and reassured me that yes it is getting better (Participant 4,

56-year-old male)

Theory of patients perspectives of patient-centred

physiotherapy

The concept of what is important to a patient from the

patients perspective is encapsulated by the following:

An understanding of the pain, . . . and a feeling that I mat-

ter and that Im a real person. . . .And then probably most

important is the . . .the knowledge that she shares and put[s]

into practice and then the encouragement to do the exercises,

because what she does is only part of it. You know, theres that

thing to get you doing the rest. . . . and . . . part of that encour-

160 M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162

agement is actually the ability . . . [to] answer questions and

. . . I think its. . .about taking the person seriously. . . .it was

respecting the questions and being prepared to answer them

and . . . that gives you, that condence. . . .its ability to inspire

condence (Participant 5, 65-year-old female)

The therapists self-condence and knowledge affect the

patients condence in both the therapist and the therapy, and

these concepts are linked to good communication, reassur-

ance and progress. The cross-concept relationship resembles

a transformative spiral of increasing condence, motivation

and progress.

Discussion

The ve categories, supporting concepts and theory pro-

vide a picture of patients perspectives of patient-centred

physiotherapy (Fig. 3). The ndings complement other recent

research on patient satisfaction and patient-centred care,

especially about the importance of communication [4,19,33].

The categories and resulting theory are generated from data

that derive directly from patients experiences, and ndings

focus solely on aspects of care that are important to the patient

(the focus of the interviewquestions). Most importantly, how-

ever, the transformative spiral of increasing condence, moti-

vation and progress extends the two-way relationship implied

by the biopsychosocial model of patient-centred care [34],

and provides more depth to the communicative relationship

(Figs. 1 and 4). The implication is that although communi-

cation underpins patient-centred care in physiotherapy [19],

no single dimension of patient-centred physiotherapy exists

without its reliance on the other dimensions.

Patients views of patient-centred physiotherapy in the

current study were situated almost entirely in the affective

domain. Although previous literature does not mention con-

dence per se as a component of patient-centred care, to

some patients, condence in the physiotherapist was depen-

dent on good communication, which is recognised [1719]

as a component of the patient-centred care model. Many of

the concepts strongly reected Mead and Bowers dimen-

sions of patient-centredness including a professional view of

the patient-as-person [34, p. 1088]; the sharing of power

and responsibility in the care relationship; and a therapeutic

alliance in which the goals and requirements of treatment are

clearly understood [4,34,35]. In the current study, most par-

ticipants emphasised this professional relationship between

therapist and patient. The passing of decision making to the

therapist because of a perceived view of professional knowl-

edge by some patients was balanced by views of others who

were encouragedtohave input intotreatment decisions. Stew-

art et al. called this relationship the common ground [36,

p. 444]; the space in which, rather than abdicating control to

the patient, clinicians use their understanding to respond to

the unique needs of the patient. Stewart reported that patients

who perceived the patient/physician relationship in terms of

common ground received fewer diagnostic tests and refer-

rals in the subsequent 2 months than patients who perceived

otherwise [14].

In this study, most participants emphasised concepts

relating to the ability to communicate, such as listening,

paraphrasing, explaining, reassuring and ensuring under-

standing. However, patients additionally focused on the

role of clear and transparent communication about instruc-

tions, information and progress when talking about other

aspects of care. Therefore, in this study, the categories

formed a composite picture of interdependent aspects of

patient care. Just as Little et al. [17] found scant evidence

of isolated domains of patient care, in this study, patients

ideas about ideal treatment were part of a spectrum of

Fig. 4. Good physiotherapy: a transformative inter-relationship.

M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162 161

care that generally related to mutual discussion and partner-

ship.

Two categories the ability to communicate, and trans-

parency of progress and outcome aligned with outcomes of

recent research on patient satisfaction [4,8,11,18,35]. How-

ever, few patients in this study referred to expectations; a

construct that features in some satisfaction literature [4,7].

This variation may be due to the fact that, in the current

study, participants were attending a public hospital clinic,

which in the NewZealand context may have created different

expectations compared with fee-paying patients:

you come here and youre not even paying but you are really

treated like a real person (Participant 2, 52-year-old female)

The relevance of this study to the profession of physiother-

apy can be considered with the question: How do patients

perspectives of important components of the patient-centred

care model inphysiotherapymatchthe components that phys-

iotherapists consider to be important? Using a grounded

theory methodology, Resnik and Jensen [32] found that col-

leagues who considered themselves or others to be good

therapists were distinguished by a patient-centred approach

to care. In particular, the patient-centred approach resulted

from the interplay of clinical reasoning, values, virtues and

therapist knowledge, and permeates and guides the clinicians

style of practice [32, p. 1095]. However, by operationally

dening such distinguishing characteristics on the basis of

collective patient outcomes, Resnik and Jensens research

only focused on professionals views rather than patients

views.

Qualitative research methodologies rely on the credibility

of the process and product. The rigour of this study lies in the

choice of methodology that is congruent with the research

question. Grounded theory was used to establish patients

perspectives of patient-centred musculoskeletal physiother-

apy. This study argues that patient satisfaction measures of

physiotherapy should be developed from patients perspec-

tives rather than those of physiotherapists, and is in part a

response to Stewart et al.s challenge [36] to ask patients

themselves to dene patient-centred care. This study used a

method that generated rich and descriptive data from a spe-

cic participant group sampled to saturation. Although the

views of a small group are just that, robust audit and anal-

ysis ensured that the results can be viewed with condence

and interpreted credibly. The generalisability of the results

beyond the musculoskeletal eld of practice is not appropri-

ate, and is an area warranting further research. In particular,

this study points to the need for more research on the meth-

ods used by clinicians to bring about favourable outcomes

through the therapeutic relationship.

Practice implications

Reporting their study on patient-centredness from the

patients perspective in chronic low back pain populations,

Cooper et al. [19] suggestedthat further researchwas required

to conrm their ndings with different patient groups. The

current study extended the scope of participants to general

musculoskeletal conditions, and suggests that, in consider-

ing components of clinical expertise, physiotherapists would

do well to consider the value that patients place on aspects

of the clinical interaction. In particular, clinician/patient

interactions that place the patient at the centre of the thera-

peutic relationship are based on: the ability to communicate;

condence; knowledge, expertise and professionalism; an

understanding of people and an ability to relate; and trans-

parency of progress and outcome. According to this study, a

clinician that fulls a combination of these dimensions places

the patient at the centre of the healthcare experience.

This study is among the rst to explore patients perspec-

tives of care in a musculoskeletal physiotherapy setting. The

responses of the patients support patient-centred care, at least

in this clinical setting, and send a clear message to clinicians

about what patients prefer in a clinical partnership.

The theory generated in this study was tested in the devel-

opment of a patient perception questionnaire which is to be

reported elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Leigh Hale and Professor

David Baxter, School of Physiotherapy, University of Otago,

Dunedin, New Zealand.

Ethical approval: Lower South Regional Ethics Committee

(Ethics reference number OTA/04/02/CPD).

Funding: Higher Education Development Unit, and Depart-

ment of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago,

Dunedin, New Zealand.

Conict of interest: None declared.

References

[1] Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts.

Soc Sci Med 1997;45:182943.

[2] Barr JK, Giannotti TE, Sofaer S, Duquette CE, Waters WJ, Petrillo

MK. Using public reports of patient satisfaction for hospital quality

improvement. Health Serv Res 2006;41:66382.

[3] Adamson J, Yoav B-S, Chaturvedi N, Donovan J. Exploring the impact

of patient views on appropriate use of services and help seeking: a

mixed methods study. Br J Gen Pract 2009;564:e22633.

[4] Sheppard LA, Anaf S, Gordon J. Patient satisfaction with physiotherapy

in the emergency department. Int Emerg Nurs; in press, corrected proof.

Available online 6 February 2010.

[5] Linder-Pelz S. Toward a theory of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med

1982;16:57782.

[6] Fitzpatrick R. The experience of illness. London: Tavistock; 1984. p.

154175.

[7] Johansson P, Olni M, Fridlund B. Patient satisfaction with nursing

care in the context of healthcare: a literature study. Scand J Car Sci

2002;16:33748.

162 M.O. Kidd et al. / Physiotherapy 97 (2011) 154162

[8] Beatti P, Dowda M, Turner C, Michener L, Nelson R. Longitudinal con-

tinuity of care is associated with high patient satisfaction with physical

therapy. Phys Ther 2005;85:104652.

[9] Nelson C. Patient satisfaction surveys: an opportunity for total quality

improvement. Hosp Health Serv Admin 1990;35:40925.

[10] Beattie P, Pinto M, Nelson M, Nelson R. Patient satisfaction

with outpatient physical therapy: instrument validation. Phys Ther

2002;82:55764.

[11] Monnin D, Perneger TV. Scale to measure patient satisfaction with

physical therapy. Phys Ther 2002;82:68291.

[12] Goldstein M, Elliott S, Guccione A. The development of an instru-

ment to measure patient satisfaction with physical therapy. Phys Ther

2000;80:85363.

[13] Wilson H. Becoming patient-centred: a review. NZ Fam Pract

2008;5:3.

[14] Stewart M. Towards a global denition of patient centred care,

the patient should be the judge of patient centred care. Br J Med

2001;322:444.

[15] Cott CA. Client centred rehabilitation: what is it and howdo we measure

it? Physiotherapy 2008;94:8990.

[16] Schattner A, Rudin D, Jellin N. Good physicians from the perspective

of their patients. Health Serv Res 2004;4:267.

[17] Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, et al.

Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in

primary care: observational study. Br J Med 2001;322:468.

[18] Potter M, Gordon S, Hamer P. The physiotherapy experience in private

practice: the patients perspective. Aust J Physiother 2003;49:195202.

[19] Cooper K, Smith BH, Hancock E. Patient-centredness in physiotherapy

fromthe perspective of the chronic lowbackpainpatient. Physiotherapy

2008;94:24452.

[20] Strutt R, Shaw Q, Leach J. Patients perceptions and satisfac-

tion with treatment in a UK osteopathic training clinic. Man Ther

2008;13:45667.

[21] Rohrer JE, Wilshusen L, Adamson SC, Merry S. Patient-centredness,

self-rated health, and patient empowerment: should providers spend

more time communicating with their patients? J Eval Clin Pract

2008;14:458551.

[22] Kval S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interview-

ing. London: Sage; 1996. p. 1937.

[23] Payne G, Payne J. Key concepts in social research. Trowbridge:

Cromwell Press Ltd.; 2004.

[24] Annells M. Grounded theory. In: Schneider Z, Elliott D, Lo-Biondo-

Wood G, Haber J, editors. Nursing research. Methods, critical appraisal

and utilisation. 2nd ed. Sydney: Mosby; 2003. p. 172.

[25] ACCPhysical therapy treatment proles handbook, 2007. Available at:

http://www.acc.co.nz (last accessed 16/06/2010). Wellington, NZ: New

Zealand Government.

[26] Hutchinson S. Qualitative research in education: focus and methods.

Philadelphia: Falmer Press; 1998. Ch. 9.

[27] Law M, Stewart D, Letts L, Pollock N, bosch J, Westmorland M, et

al. Guidelines for critical review form. Critical review form for quali-

tative studies. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University Occupational

Therapy Evidence-based Practice Research Group; 1998.

[28] Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory: emergence versus forcing. Mill

Valley: Sociology Press; 1992.

[29] Edwards I, Jones M, Carr J, Braunack-Mayer A, Jensen GM. Clinical

reasoning strategies in physical therapy. Phys Ther 2004;84:31230.

[30] Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and

procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: Sage

Publications; 1998. p. 22.

[31] Whittemore R, Kna K. The integrative review: updated methodology.

J Adv Nurs 2005;52:54653.

[32] Resnik L, Jensen G. Using clinical outcomes to explore the theory of

expert practice in physical therapy. Phys Ther 2003;83:10956.

[33] Trice ED, PrigersonHG. Communicationinend-stage cancer: reviewof

the literature and future research. J Health Commun 2009;14:95108.

[34] Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centeredness: a conceptual framework and

review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:108890.

[35] Reeve S, May S. Exploration of patients perceptions of quality within

an extended scope physiotherapists spinal screening service. Physio-

ther Theory Pract 2009;25:53343.

[36] Stewart M, Brown J, Donner A, McWhinney I, Oates J, Weston WW,

et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract

2000;49:797.

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

You might also like

- Muscle Origin Insertion ActionsDocument14 pagesMuscle Origin Insertion ActionsAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- A Statistical Architecture For Economic Statistics: Ron Mckenzie Ices IiiDocument34 pagesA Statistical Architecture For Economic Statistics: Ron Mckenzie Ices IiiRishikesh KaushikNo ratings yet

- Impact Factor 2016Document233 pagesImpact Factor 2016Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Bio EnergeticsDocument23 pagesBio EnergeticsAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Bers Resp No Anim 03Document65 pagesBers Resp No Anim 03Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Anatomy Exam 1 Review - Muscles of the Back, Shoulder, Arm, Forearm & HandDocument27 pagesAnatomy Exam 1 Review - Muscles of the Back, Shoulder, Arm, Forearm & Handgdubs215No ratings yet

- 13 CIN Respiratory Assessment NotesDocument29 pages13 CIN Respiratory Assessment NotesAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Uk and Countries March 2017 v1Document16 pagesChartered Society of Physiotherapy Uk and Countries March 2017 v1Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Icahe Oc Incontinence User ManualDocument118 pagesIcahe Oc Incontinence User ManualAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Phy Kompetenzprofil Englisch Fin 02106Document22 pagesPhy Kompetenzprofil Englisch Fin 02106Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- MDT World Press Newsletter Full PDF Vol2No3Document19 pagesMDT World Press Newsletter Full PDF Vol2No3Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- c1Document7 pagesc1Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Patients' Rights in the European Union OverviewDocument30 pagesPatients' Rights in the European Union OverviewAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Egeszsegugyi Ellatas Fuzet EngDocument16 pagesEgeszsegugyi Ellatas Fuzet EngAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Health Services Co108 enDocument11 pagesHealth Services Co108 enAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Evidence Informed Practice Position Statement EnglishDocument2 pagesEvidence Informed Practice Position Statement EnglishAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- 2012-2173 Physical Agent Catalog - 2Document16 pages2012-2173 Physical Agent Catalog - 2Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Behavior and MedicineDocument32 pagesBehavior and MedicineAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Electrotherapy For Neck Pain (Review)Document106 pagesElectrotherapy For Neck Pain (Review)Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Colleague and Patient Questionnaires - PDF 44702599Document12 pagesColleague and Patient Questionnaires - PDF 44702599Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- 02 Leveraging Employee Engagement For Competitive Advantage 2Document12 pages02 Leveraging Employee Engagement For Competitive Advantage 2faisalsiddique100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Clinical Data Fisiotek HP2Document28 pagesClinical Data Fisiotek HP2Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Nu e Nimic InteresantDocument10 pagesNu e Nimic InteresantAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Un Peu Du Ethics Pour RehabilitationDocument8 pagesUn Peu Du Ethics Pour RehabilitationAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- The Physiotherapy Workforce Is Ageing, Becoming More Masculinised, and Is Working Longer Hours: A Demographic StudyDocument6 pagesThe Physiotherapy Workforce Is Ageing, Becoming More Masculinised, and Is Working Longer Hours: A Demographic StudyAlexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Scheda I-Tech Ue - Eng (Sp21-00)Document2 pagesScheda I-Tech Ue - Eng (Sp21-00)Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Should I: Warn The Patient First?Document7 pagesShould I: Warn The Patient First?Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- J Hist Med Allied Sci 2005 Linker 320 54Document35 pagesJ Hist Med Allied Sci 2005 Linker 320 54Alexandra NadinneNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Psychotherapy Definition, Goals and Stages of PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesPsychotherapy Definition, Goals and Stages of PsychotherapycynthiasenNo ratings yet

- Magna Carta: Republic Act 7305: Magna Carta of Public Health WorkersDocument50 pagesMagna Carta: Republic Act 7305: Magna Carta of Public Health WorkersZyrene RiveraNo ratings yet

- Restless Leg Syndrome Part 1Document2 pagesRestless Leg Syndrome Part 1Faried MananNo ratings yet

- Hands Only CPRDocument14 pagesHands Only CPRabhieghailNo ratings yet

- African Swine FeverDocument4 pagesAfrican Swine FeverShean FlorNo ratings yet

- Brain Cancer ReportDocument5 pagesBrain Cancer ReportCrisantaCasliNo ratings yet

- Assignment - EugenicsDocument11 pagesAssignment - EugenicsNavneet GillNo ratings yet

- Including Disabled People in Sanitation and Hygiene ServicesDocument8 pagesIncluding Disabled People in Sanitation and Hygiene ServicesRae ManarNo ratings yet

- Arellano University: Andres Bonifacio Campus College of Arts and Sciences Psychology DepartmentDocument97 pagesArellano University: Andres Bonifacio Campus College of Arts and Sciences Psychology DepartmentJohn Michael MortidoNo ratings yet

- Department: Infectious Disease EpidemiologyDocument6 pagesDepartment: Infectious Disease EpidemiologyMuhammad Zoraiz IlyasNo ratings yet

- Foodborne Illness (Also Foodborne Disease and Colloquially Referred To As Food Poisoning)Document17 pagesFoodborne Illness (Also Foodborne Disease and Colloquially Referred To As Food Poisoning)Helen McClintockNo ratings yet

- Sir Iqbal First PageDocument7 pagesSir Iqbal First PageMozzam Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Dengue QuizDocument10 pagesDengue QuizAfifah SelamatNo ratings yet

- Giant Ovarian Cyst Mimicking AscitesDocument3 pagesGiant Ovarian Cyst Mimicking AscitesbellastracyNo ratings yet

- Sample Paper 2 Iatf Protocol1Document103 pagesSample Paper 2 Iatf Protocol1Tiny Grace PalgueNo ratings yet

- HRD-55-Daily-Accomplishment-Report-for-Job-Order-Employees LHEE MARCH 2023Document2 pagesHRD-55-Daily-Accomplishment-Report-for-Job-Order-Employees LHEE MARCH 2023Miguel PagkalinawanNo ratings yet

- The Battle Against Workplace Stress - PDF Read ArticleDocument12 pagesThe Battle Against Workplace Stress - PDF Read ArticleRama KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Retropharyngeal Abscess (RPA)Document15 pagesRetropharyngeal Abscess (RPA)Amri AshshiddieqNo ratings yet

- Static Stretch and Upper HemiDocument9 pagesStatic Stretch and Upper Hemisara mohamedNo ratings yet

- Shock TraumaDocument37 pagesShock TraumaMaica LectanaNo ratings yet

- Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) (J) : State Institute of Health & Family Welfare, JaipurDocument39 pagesJanani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) (J) : State Institute of Health & Family Welfare, JaipurvipinyadavkumarNo ratings yet

- HER2 Targeted Therapy For Early and Locally Advanced Breast CancerDocument58 pagesHER2 Targeted Therapy For Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancerreny hartikasariNo ratings yet

- Work-Life Balance - Facebook Com LinguaLIBDocument257 pagesWork-Life Balance - Facebook Com LinguaLIBDiegoAngeles100% (1)

- Klasifikasi TindakanDocument53 pagesKlasifikasi TindakanDinda SehanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Student Cover LetterDocument8 pagesNursing Student Cover Letterafmrpaxgfqdkor100% (1)

- COVID 19 and Vitamin D YudhaFazaDeasDocument44 pagesCOVID 19 and Vitamin D YudhaFazaDeasrohana agustinaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Clinical Reasoning To Medical Students: A Case-Based Illness Script Worksheet ApproachDocument7 pagesTeaching Clinical Reasoning To Medical Students: A Case-Based Illness Script Worksheet Approachstarskyhutch0000No ratings yet

- Meal Plan MenDocument35 pagesMeal Plan Menoddo_mneNo ratings yet

- BAHASA INGGRIS CLASSROOM BiranDocument22 pagesBAHASA INGGRIS CLASSROOM BiranBiran Harianto AkbariNo ratings yet

- Are Adopted Children As Mentally Healthy As Children Who Stay With Their Birth Parents 2Document4 pagesAre Adopted Children As Mentally Healthy As Children Who Stay With Their Birth Parents 2api-558988793No ratings yet