Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 S0305750X11001306 Main

Uploaded by

jktinarpidwaotkiimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 S0305750X11001306 Main

Uploaded by

jktinarpidwaotkiimCopyright:

Available Formats

Detecting Gender and Racial Discrimination in Hiring Through

Monitoring Intermediation Services: The Case

of Selected Occupations in Metropolitan Lima, Peru

q

MARTI

N MORENO

Penn State University, USA

HUGO N

OPO

Inter-American Development Bank, USA

JAIME SAAVEDRA

World Bank, USA

and

MA

XIMO TORERO

*

IFPRI, USA

Summary. Inspired by audit studies methodology, we monitored a job intermediation service in Peru to detect gender and racial dis-

crimination in hiring. We capture individual racial information using the approach of N

opo, Saavedra, and Torero (2007), enabling a

richer exploration of racial dierences. Overall, the study nds discriminatory treatment in hiring only when comparing groups with

extremely dierent observable racial characteristics. We detect discriminatory treatment for female Indigenous applicants in secretarial

positions. In terms of aimed wages, females tend to ask for wages 7% below those of males with comparable skills (although this has no

negative impact on wages at hiring).

2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Key words eld experiments, discrimination, occupational segregation

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite social advances and a movement toward moderniza-

tion of labor markets, especially in Latin America, substantial

dierences in earnings and opportunities for individuals from

dierent gender and racial groups persist. A simple observa-

tion of job openings posted in local newspapers reects the

existence of occupations for which employers request only

male or only female employees. In other postings, the euphe-

mism good presence is used to refer to employers specic

racial preferences for particular job openings. Occupational

dierences that are linked to racial characteristics continue

due to the existence of stereotypes and prejudices. These biases

are reinforced by dierences in individuals access to education

and other assets. Furthermore, cultural dierences, often ob-

servable through behavior and mode of speech, should be

added to the dierences that are based on phenotypic charac-

teristics. Sometimes employers make their decisions using ra-

cial and ethnic characteristics as proxy measures for

attributes that they seek but that are harder to observe in a

job interview. As a result, some employers discriminate against

individuals on the basis of their racial characteristics, but not

because they have a taste for discrimination. Instead, these

employers discriminate because they use race as a signaling de-

vice, which is representative of statistical discrimination

(Coate & Loury, 1993; Yinger, 1998).

Gender dierences in occupations in Latin America are very

high when compared to the rest of the world (Blau & Ferber,

1992; Deutsch, Morrison, Piras, & N

opo, 2002). More specif-

ically, in Peru, there are substantial dierences in occupations

among gender and racial groups; and these dierences account

for earnings and wealth dierentials (N

opo et al., 2007). How-

ever, analyzing gures on segregation is not sucient in iden-

tifying whether this is a discriminatory outcome or not. This

study attempts to isolate and explore discrimination in

employers hiring decisions. It analyzes the hiring processes

for specic occupations using information from the job inter-

mediation service of the Peruvian Ministry of Labor and

Employment Promotion. The study focuses on three types of

occupations: salespersons, secretaries, and accounting and

administrative assistants. For this purpose, the experiment in-

volved monitoring the job postings in these occupations and

all corresponding processes in lling the vacancies (pre-screen-

ing of candidates, job interviews, and the nal hiring deci-

sions). For each job posting information was collected on

gender and racial characteristics of all applicants, as well as

q Previous versions of this paper circulated as Gender and Racial

Discrimination in Hiring: A Pseudo-Audit Study for Three Selected

Occupations in Metropolitan Lima.

*

We thank the Inter-American Development Bank and the Global Devel-

opment Network for their nancial support in a substantial component of

this project. The comments of Je Carpenter, Alberto Chong, Loujia Hu,

Jacqueline Mazza, Andrew Morrison, Claudia Piras, and Chris Taber, as

well as the assistance of Sebastian Calo nico, Deidre Ciliento, Cristina

Gomez, and Lucas Higuera are greatly acknowledged. Final revision acc-

epted: May 10, 2011.

World Development Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 315328, 2012

2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

0305-750X/$ - see front matter

www.elsevier.com/locate/worlddev

doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.003

315

the attributes that would make them employable for the occu-

pations for which they were applying. This study shares many

characteristics present in traditional audit studies, but it sur-

mounts some of the critiques highlighted by Heckman

(1998), although at a cost.

Following this brief introduction, the next section presents

some stylized facts about the labor markets in Peru, emphasiz-

ing occupational segregation, both by gender and race. In

addition, it introduces methodological considerations that

are necessary to take into account when analyzing racial dier-

ences in a post-colonial society like the Peruvian in which ra-

cial mix prevails and traditional ways of measuring race fail to

capture the vast heterogeneity behind this concept. Later,

Section 3 outlines the basic aspects of the audit studies meth-

odology, as well as its main criticisms, highlighting the similar-

ities and dierences between that methodology and the one

employed in this study. Section 4 describes the dataset, show-

ing the main characteristics of the sample of applicants and the

sample of rms. Results of the experiment are presented in

Section 5, which is followed by a conclusion in Section 6,

discussing the studys scope in the understanding of discrimi-

nation in the developing world.

2. OCCUPATIONAL SEGREGATION BY GENDER

AND RACE IN PERU

Measured by the Duncan Index, occupational segregation

by gender in Latin America is high relative to the rest of the

world; and Peru is not dierent from those of the region.

1

Using data from the Peruvian National Household Survey

from the year 2000 (ENAHO 2000), with a classication of se-

ven occupational groups,

2

the segregation index between

males and females reaches 0.3265; meaning that it would be

necessary for at least 32.65% of the working females to switch

occupations into those that have higher male representation,

or vice versa, in order to achieve a non-segregated work

force.

3

But, high occupational segregation in Peru occurs

not only by gender, but also by race. Just like the existence

of male-dominated and female-dominated occupations, the

study provides evidence on the existence of White-dominated

and Indigenous-dominated occupations.

The Peruvian ENAHO 2000 used in this study to show the

Duncan Index for gender segregation was complemented by a

module of ethnic and racial characteristics. N

opo et al. (2007)

show a description of such module and explore the role of ra-

cial mixing on earnings in urban Peruvian labor markets. An

innovative element of the racial module is the way in which

information on race was captured. Instead of using the tradi-

tional classication in which each individual falls into one and

only one racial category, the module proposes the use of inten-

sities along two basic dimensions of race that are prevalent

in Peru (White/Caucasian and Indigenous). The intensity scale

ranges from 0 to 10 and corresponds to a series of observable

individual characteristics that make them resemble a particu-

lar racial group. The higher the intensity, the higher the resem-

blance of an individual with a typical member of a racial

group. For example, an individual with intensities 9 and 1 in

the corresponding White/Caucasian and Indigenous dimen-

sions would resemble a typical White individual; analogously,

an individual with intensities 1 and 8 would represent a typical

Indigenous, whereas an individual with intensities 4 and 6, for

example, would resemble a typical Mestizo.

4

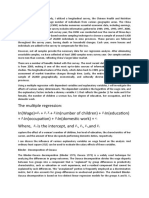

Next, we use racial intensities along the two basic dimen-

sions to illustrate some of the patterns of racial dierences in

occupations. Figure 1 shows the proportion of White-collar

workers, by racial intensity, of the urban Peruvian population

in 2000. As individuals are categorized with higher intensities

in the White dimension, the likelihood that they are employed

in White-collar occupations rapidly increases. Only one out of

ve individuals, with White intensity 0, works in White-collar

occupations, while nearly 100% of individuals with White

intensity 10 are employed in such occupations. The relation-

ship is the opposite in the case of Indigenous dimension: the

higher the intensity, the lower the proportion of white-collar

workers.

Analyzing the seven occupational categories described

above, the study computes the Duncan Indices that result from

the comparison of those individuals with racial intensity zero

with dierent groups of higher intensities, separating the com-

parison by gender. The results of comparison in the Indigenous

dimension are presented in Figure 2.

Dierences in individuals racial characteristics and occupa-

tions increase simultaneously. Moreover, this result is more

pronounced among females than males. In order to achieve a

non-segregated work force, it would be necessary for at least

16% of females reporting Indigenous intensity 1 switch their

occupations with the group that has Indigenous intensity 0.

The equivalent gure for males is 6%. A similar White dimen-

sion analysis produces results that show that the levels of occu-

pational segregation increase relatively more when comparing

individuals that report characteristics making thembe perceived

as indisputably White. These results are reported in Figure 3.

In summary, national statistics report that Peruvian labor

markets are segregated, by both gender and race. From the

information provided so far, it is not possible to distinguish

whether these results are the outcome of a series of individual

decisions of self-segregation, or the result of employers dis-

criminatory practices of either statistical or taste-based nature.

The following section presents the methodology employed in

this study to unravel possible explanations behind these na-

tional outcomes.

3. DESIGN OF THE PSEUDO-AUDIT STUDY

According to the taxonomy of experiments proposed by

Harrison and List (2004), this study could be classied as a

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

P

r

o

p

o

r

t

i

o

n

Indigenous White

Figure 1. Proportion of White collars by racial intensities. Note: The

horizontal axis captures the racial dierences resulting from a score-based

procedure carried out by pollsters (see Torero et al. (2004); N

opo et al.

(2007) for details). Each individual received an independent score of 010

from a pollster in each of four categories: Asian, White, Indigenous, and

Blackgroups that people readily recognize as distinct racial groupswith

zero indicating no physical characteristics that resembled a specic race and

10 indicating most features of that group. For example, an individual with

intensities 2 (White), 8 (Indigenous), 0 (Black), and 1 (Asian), would be

considered predominantly Indigenous. Thus, the horizontal axis captures the

proportion of individuals within each indigenous intensity that where

White collar.

316 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

Natural Field Experiment (NFE). It is a NFE and not a tradi-

tional Field Experiment (FE) in the sense that we did not have

the ability to exogenously randomize treatments across the

population under study, it just naturally happened from the

functioning of the market, as it will be shown next in this sec-

tion. Our approach to detect discrimination in hiring practices

was inspired by the audit studies literature.

5

The audit studies

try to verify the hypothesis of discriminatory behavior of a

decision-maker, simulating the interviews of a group of

observably similar applicants called auditors. The simulation

is repeated for many decision makers, and when the outcome

statistically favors, or hurts, individuals with a particular set of

characteristics the conclusion is that individuals who show

such characteristics are discriminated in favor, or against.

As mentioned earlier in this paper, the audit methodology

has received some criticisms.

6

Generally, the auditors are indi-

viduals hired for the purposes of the study; they are mostly

college students that view their participation as a source of in-

come. They arrive at job interviews with similar resumes that

are specically tailored for the study; therefore, auditors

applying for the same position present comparable informa-

tion to decision makers. They are trained to show up for inter-

views and pretend to be interested in getting a job. In addition,

they are required to act as if they have the education and expe-

rience that their resumes claim. In order to keep to a minimum

the possible dierences in observable characteristics, the occu-

pations examined in these studies typically require minimal

skills. Finally, the designers of the study nd the job openings

in newspapers.

These characteristics of the audit studies imply the following

problems:

(1) An auditor does not necessarily put in the same level of

eort to get a job as a real job-seeker would. Also, it is not

possible to ensure that the auditor will experience the same

pressure and anxiety that would be present in a real job

interview.

(2) The auditor knows the purpose of the study and, as it is

documented in experimental psychology literature, this

may generate incentivesconscious or notto skew the

results toward the desired outcome of the researchers

(Lindzey & Aronson, 1975; Rosenthal, 1976).

(3) Descriptions of job requirements that appear in news-

papers are rarely exhaustive. Therefore, the role of unob-

servable characteristics, that would be of interest to

employers during interviews, but that designers of audit

studies do not take into account when forming auditor

groups, can be important.

Hence, there are some reasons to be suspicious about the re-

sults that come from audit studies, as there are many sources

of statistical noise that could challenge the results. Some of the

problems mentioned above are addressed during the audit

with a slight modication of the approach: using the resumes

of ctitious job applicants instead of having face-to-face (or

telephone) interviews. The drawback of this strategy is the

inability to test for the nal hiring decisions. It only allows

us to test for hypothetical hiring decisions of the employers

(van Beek, Koopmans, & van Praag, 1997) or for a one-step

advancement of the applicants in the hiring process (Bertrand

& Mullainathan, 2004), although perhaps the most important

one (Zegers de Beijl, 2000).

This study overcame some of these critiques by designing a

NFE in which, instead of hiring auditors to go to the job inter-

views, we selected them from a pool of applicants at the job

intermediation service of the Ministry of Labor and Employ-

ment Promotion in Lima, Peru, the CIL-PROEMPLEO net-

work.

7

With more than 10 years of functioning, this

network is the biggest public job intermediation service in

Lima, Peru. It receives around 500 job seekers per day, inter-

mediating approximately 40,000 positions per year. It has a

well established reputation among rms for the speed and

quality of the services they provide. A brief description of its

functioning follows.

Every morning, the intermediation specialists interview job

applicants at the oces of CIL-PROEMPLEO. After each

interview the information of the applicant is entered into a

database and remains there for a time-window of up to

3 months. If at the moment of the interview there is a

vacancy for which the applicant is qualied, he/she is

immediately sent to the rm that posted the vacancy, with

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 to 10

Intensities

D

u

n

c

a

n

I

n

d

e

x

Females Males

Figure 3. Duncan Index of occupational segregation by intensities in the

White dimension (base group = intensity 0). Note: The Duncan Index was

calculated for each race intensity for males and females within the White

dimension. Each individual received an independent score of 010 from a

interviewer in each of four categories: Asian, White, indigenous, and

blackgroups that people readily recognize as distinct racial groupswith

zero indicating no physical characteristics that resembled an specic race

and 10 indicating most features of that group. Thus, the horizontal axis

captures the Duncan Index for each level of intensity for the White

category. For example, a female with intensity 4 (White) will have a

Duncan Index of 0.24.

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 to 10

Intensities

D

u

n

c

a

n

I

n

d

e

x

Females Males

Figure 2. Duncan Index of occupational segregation by intensities in the

indigenous dimension (base group = intensity 0). Note: The Duncan Index

was calculated for each race intensity for males and females within the

Indigenous dimension. Each individual received an independent score of 0 to

10 from a interviewer in each of four categories: Asian, White, indigenous,

and blackgroups that people readily recognize as distinct racial groups

with zero indicating no physical characteristics that resembled an specic

race and 10 indicating most features of that group. Thus, the horizontal axis

captures the Duncan Index for each level of intensity for the indigenous

category. For example, a female with intensity 4 (indigenous) will have a

Duncan Index of 0.27.

GENDER AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING THROUGH MONITORING INTERMEDIATION SERVICES 317

a letter of recommendation from the intermediation service,

for a job interview at the rm. If there is no suitable vacancy

at the moment, the applicant is asked to go home and wait

until one appears. When such vacancy appears, the applicant

is called by phone and asked to show up at the CIL-PRO-

EMPLEO oces to receive the recommendation letter and

go to her/his job interview. The vacancies are received on a

continuous basis, online or by phone, by the same intermedi-

ation specialists and immediately entered into the database

(which is shared by all intermediation specialists). The dat-

abases of applicants and vacancies are linked using software

that helps the intermediation specialists in their matching

tasks. Such software also facilitates the monitoring of the

rms and applicants matching processes such that the inter-

mediation system always has up-to-date information about

open and closed vacancies, and active and inactive job seek-

ers. Note that one rm may post more than one vacancy on

the system at the same time. Additionally, one applicant can

apply to more than one posting, as long as s/he satises the

requirements of each posting.

With the permission from the Ministry of Labor, a pool of

monitors at the CIL-PROEMPLEO oces was installed for

the purposes of this study, so that before the applicants were

sent to the rms for their nal job interviews, they were inter-

viewed for this project. Such interviews made it possible to col-

lect complementary information about applicants, in addition

to what was already registered in the administrative databases

of the intermediation service. The applicants were asked about

additional labor and socio-demographic characteristics

(including their aimed wages at the job for which they were

applying), a picture of them was taken and their racial inten-

sities were registered in our database. Such racial intensities

were based on observable characteristics, such as the skin col-

or, hair color, and shape and color of eyes, among others (see

Torero, Saavedra, N

opo, & Escobal (2004) for details on the

methodology to measure racial intensities). The monitors were

trained to homogenize the criteria used to translate the obser-

vable characteristics into intensities in the four-dimensional

scale.

8

In the cases in which the applicant was sent to a job

interview from an oce other than the headquarters, the pool

of monitors visited the applicant at home.

The monitors were also sent to the rms that posted the

vacancies in order to apply a questionnaire to the job inter-

viewers. Under the guise of conducting a survey about the

quality of services of CIL-PROEMPLEO, the monitors ob-

tained information about personal characteristics of interview-

ers, such as schooling, tenure, and age. This information

complemented the one that CIL-PROEMPLEO already had

about rms and vacancies characteristics.

Therefore, as opposed to taking the demand side of the

labor market as a given and simulating the supply side with

auditors, this study monitored both sides of the market.

There was no need to hire a pool of auditors, only a pool

of monitors. This is crucial in avoiding problems related

to points 1 and 2 mentioned earlier regarding audit studies.

On the other hand, since the CIL-PROEMPLEO network

has direct contact with the rms that post the job openings,

they have near perfect information of the requirements at-

tached to each job posting. The information related to the

observable characteristics that rms require is more com-

plete than the information that one could obtain from read-

ing a job posting in the newspaper. By having a richer set of

information about observable characteristics, the room for

those that are unobservable, in the sense enunciated in point

3 above, is substantially smaller. Hence, CIL-PROEMPLEO

can send homogeneous groups of applicants to interviews,

more than what could have been expected from a traditional

audit study (Table 1).

9

4. SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

This study examines three occupations with the highest vol-

umes of intermediation through CIL-PROEMPLEO: account-

ing and administrative assistants, secretaries, and

salespersons.

10

There were 1,557 applicants interviewed be-

tween September 2002 and March 2003, who submitted 2,650

applications for 435 job postings oered by 202 dierent rms.

On average, each individual applied to 1.7 openings. The infor-

mation for 43% of the applicants was not used because the ini-

tial postings were canceled by the rm, either because the rm

hired someone from outside of the system or because the open-

ing was closed without any hiring. Also, for some other post-

ings, CIL-PROEMPLEO sent only one applicant to the rm,

either by the request of the rm or because there were no other

qualied applicants at the moment of the posting. These obser-

vations were also left out because it is not possible to detect dis-

crimination when an applicant has no competitors. For those

reasons, the number of observations was initially reduced to

882 applicants, 1713 applications and 292 postings (referred

as the Valid Sample in Table 2). An additional group of 55

of the 202 surveyed rms were excluded from the study because

of missing observations for one or more of the applicants. Fi-

nally, combining the restrictions imposed on the data, there

were 91 rms left, 113 postings, 565 applicants, and 760 appli-

cations (referred as constrained sample in Table 2).

(a) The sample of applicants

The sample of individuals for this study was composed of

technicians and professionals from the middle and lower in-

come classes of metropolitan Lima. They were relatively

young and generally had more than a high school education.

The average number of years of schooling was 13.6, with a

standard deviation of 1.9. Only 20% of the individuals did

not study after high school while 23% graduated from a pri-

vate high school. Their parents education was on average less

than their own. A majority of the parents only nished high

school.

Table 1. Entire sample

Total sample

a

Valid sample

b

Constrained sample

c

Applications 2650 1713 760

Individuals 1557 882 565

Postings 435 292 113

Firms 202 146 91

a

Includes applicants sent to postings that were canceled by the rm or to

postings with only one applicant.

b

Includes postings for which we have information about all the applicants

sent.

c

Includes postings for which we have information about all the applicants

and the interviewers.

Table 2. Sample by occupations

Frequency % Accumulated

Salespersons 227 29.9 29.9

Accounting/administrative

assistant

183 24.1 54.0

Secretary 350 46.1 100.0

Total applications 760 100

318 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

Almost all the applicants had some work experience, 87%

worked during the last twelve months as a dependant and

50% were self-employed. This overlap reveals the presence of

individuals with secondary occupations. Among those who

worked as dependants, the average monthly earnings in their

last occupation exceeded the minimum wage by 50% and were

close to the average monthly earnings in metropolitan Lima.

The average unemployment spell of applicants was 3.5 months.

Of all applicants, 36% reported having the required on-the-job

experience for the position, and those gures were substantially

higher among secretaries and accounting assistants.

Two thirds of the applicants were females. In the sample, fe-

males were, on average, one year younger than males and

came from families with a higher average income, although

this dierence is not signicant. The percentage of females

who experienced at least one unemployment period during

the last 12 months was smaller than the percentage of males.

Household and per-capita income were generally higher for

individuals who attended high school at a private institution,

had done some technical or professional studies at a univer-

sity, and whose parents received post-high-school diplomas,

either at universities or vocational institutions. The individuals

who attended private institutions for their technical or profes-

sional degrees had earnings that, on average, were not sub-

stantially above the earnings of those who had attended

public institutions for the same degree.

11

Regarding racial characteristics, individuals with high inten-

sities along the Indigenous dimension are prevalent among

both applicants and interviewers. Table 3 illustrates the distri-

bution of the applicants racial intensities.

In order to make the racial categorizations somewhat com-

parable to those found in traditional surveys, it is necessary to

dene a criterion to classify the population. As a result, the

sample is divided into three racial groups: Indigenous, White,

and Mestizo. Considering that the population under study

represents a particular segment of the national population, a

relative cut-o criterion was used. The cut-o is dened using

the distribution of racial characteristics of the sample in the

following way:

(1) If an individuals Indigenous intensity variable has a

value greater than a cut-o c and her/his White intensity

variable is smaller than the same cut-o c, s/he will be

considered Indigenous.

(2) Similarly, if an individuals White intensity variable has

a value greater than a cut-o c and her/his Indigenous

intensity variable is smaller than the same cut-o c, s/

he will be considered White.

(3) An individual that is considered neither Indigenous nor

White will be considered Mestizo.

For the main results, the medians of distributions of race

intensities in the White and Indigenous dimensions are used,

respectively, as cut-o points, c. Further, Section (c) will

analyze the sensitivity of these results for other possible cut-

o points. Using the median cut-o, 45% of the population

can be classied as Indigenous, 10% as Mestizo, and 45% as

White. There was a prevalence of Indigenous applicants apply-

ing for accounting and administrative assistant positions and a

prevalence of White individuals applying for salespersons and

secretarial positions (Table 4). Figure 4 presents a set of indi-

vidual and family characteristics for males and females, as well

as for the three occupations under study. For most variables, a

comparison of applicants from dierent gender groups does

not denote the existence of clearly dened patterns. However,

the study found some dierences in the asset ownership of the

households, the applicants type of education (public/private)

and the parents schooling for dierent racial groups (not

shown in the table).

(b) The sample of interviewers

The main demographic, education, and labor characteristics

of the interviewers that were surveyed, suggest that they consti-

tute a relatively homogeneous group. However, some dier-

ences in these characteristics were linked to the size of the

rm for which they worked. Overall, interviewers were equally

split by gender, but as the rm size increased, the prevalence of

males increased as well (60% in large rms as compared to 40%

in small rms). The average age showed a similar pattern. The

average age in the sample was 40 years; however, the average

age of males was higher than that of females, 42 and 35 years,

respectively. In small rms the average age of interviewers was

higher than the average age of those in medium and large

rms. Furthermore, 80% of the interviewers received a college

degree and this percentage was higher among large rms. The

distribution of professional degrees varied by rm size. In

small rms the interviewers area of expertise coincided with

areas for which they required applicants: accounting, adminis-

tration, economics, or engineering. Meanwhile, in large rms,

the interviewers area of expertise was related to positions that

were typically in charge of personnel selection processes: psy-

chologists or industrial relations professionals. Males had

longer job tenure (7 years) and experience (5 years) than fe-

males (5 and 4 years, respectively). Finally, the interviewers

racial intensities in the Indigenous dimension are concentrated

around six, while in the White dimension they are around three

(Table 5). Applying the same cut-o criterion that was used to

classify the applicants, the sample of interviewers was divided

into three groups: 13% of the interviewers were Mestizo, 46%

White, and 41% Indigenous, as seen in Table 5.

5. RESULTS OF THE NATURAL FIELD EXPERIMENT

(a) Gender and racial dierences in hiring

Out of 760 applications in the constrained sample, 127

individuals who were interviewed for jobs were hired. This is

translated into a success rate of 16.71%. Looking separately

at the three occupations under consideration, the study can

Table 3. Percentage of applications and individuals by race group

Total applications Total individuals

Total Salesperson Secretaries Assistants Total Salesperson Secretaries Assistants

Indigenous 45.3 39.6 33.9 54.9 45.1 42.0 32.3 55.5

Mestizo 10.1 5.7 13.1 11.4 8.0 5.9 11.3 7.9

White 44.6 54.6 53.0 33.7 46.9 52.2 56.4 36.6

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

GENDER AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING THROUGH MONITORING INTERMEDIATION SERVICES 319

report success rates of 14.54% for the salespersons positions,

20.22% for the secretaries, and 16.29% for the assistants.

12

The design of the eld experiment requires that all appli-

cants who are sent to the same job interview satisfy a minimum

set of requirements, which are established by the posting rm

and veried by CIL-PROEMPLEO. However, it is not possi-

ble to ensure that all the applicants that go to the same inter-

view have exactly the same set of observable characteristics. If

applicants for the same position dier in observable character-

istics, it is necessary to control for them. For that purpose, the

study estimates discrete models (logit) where the explained

variable is whether the individual was hired or not. This hiring

outcome is explained by a set of observable characteristics:

applicants sex and race, interviewers characteristics (race,

Table 4. Household and individual characteristics of the applicants by gender and occupations

Gender of the applicant Occupations

Total Male Female Salesperson Secretary Accounting/administrative

assistants

Demographic characteristics

Females 71% 0% 100% 57% 100% 69%

Age (in years) 28.01 29.21 27.52 27.04 28.54 28.61

Migratory experience

Born in Lima 75% 71% 77% 75% 77% 77%

Born in Lima and never migrated 68% 62% 70% 66% 68% 73%

Socio-economic characteristics

Household size (persons) 4.94 4.57 5.09 4.88 4.87 5.31

Monthly household income (S/.) 1339.27 1237.31 1379.13 1125.33 1421.43 1496.84

Monthly household income, per-capita (S/.) 298.35 297.21 298.80 252.03 327.99 307.61

Household assets

Microwave oven 20% 20% 20% 15% 28% 18%

Washing machine 33% 36% 32% 27% 46% 30%

Dryer 3% 2% 3% 2% 5% 4%

Car 17% 13% 18% 14% 16% 19%

Educational background (individual)

Years of education 13.56 13.71 13.50 12.46 12.61 14.93

Attended high school in a

Public institution 77% 81% 75% 79% 69% 79%

Private institution 23% 19% 25% 21% 31% 21%

Pursued superior studies in

Public University 16% 21% 14% 7% 3% 35%

Private University 17% 19% 16% 12% 9% 23%

Public Technological Institute 13% 8% 15% 8% 8% 22%

Private Technological Institute 28% 31% 27% 27% 38% 19%

Others 5% 6% 4% 9% 12% 0%

Without superior studies 21% 16% 23% 37% 31% 2%

Educational background (family)

Fathers educational level

Elementary 24% 24% 24% 20% 20% 26%

High school 45% 45% 45% 50% 44% 41%

College or higher 31% 31% 31% 30% 36% 33%

Mothers educational level

Elementary 34% 31% 35% 28% 32% 37%

High school 46% 47% 45% 50% 43% 46%

College or higher 21% 22% 20% 22% 25% 16%

Labor history

Has worked once in his life 99% 100% 99% 100% 99% 99%

Labor experience (in years) 3.85 4.34 3.66 3.44 4.49 3.80

Worked as a dependent during the last 12 months 87% 82% 90% 85% 88% 88%

Monthly Earnings in their last dependent occupation 645.07 704.45 622.87 547.97 675.57 708.76

Last employment spell (years) 13.41 14.66 12.95 11.78 13.99 12.69

Worked as a self-employed in the last 12 months 49% 61% 44% 53% 37% 54%

Job searching

Unemployment spell (months) 3.64 4.03 3.49 4.06 3.21 3.22

Months looking for a job 2.22 2.56 2.09 2.53 1.77 2.02

Applications sent to PROEMPLEO 1.35 1.26 1.38 1.22 1.83 2.33

Has prior experience at the job 34% 26% 37% 17% 46% 43%

Hired (%) 18% 15% 19% 15% 20% 16%

Number of observations 565 163 402 227 183 350

320 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

gender, age, educational level, and job experience), human

capital characteristics of the applicant (educational level), per-

sonal characteristics of the applicant (age, marital status, a

dummy indicating whether the applicant is head of a house-

hold or not, and another dummy for migratory status), labor

market characteristics of the applicant (employment status,

unemployment spell, and occupational experience), rms

characteristics (number of workers and economic sector) and

applicants family controls (education of their parents).

In addition, in an attempt to capture unobservable charac-

teristics related to the productivity and expectations of the

individuals, the analysis incorporated two variables: the loga-

rithm of their wages at their last job and the logarithm of their

aimed wages. It is understandable that these last two variables

are possibly highly correlated, there was no attempt to inter-

pret the resulting logit coecients for these two variables,

and they are included in the regressions merely as additional

controls. Also, in an attempt to account for the characteristics

of the competitors that every individual faced at each job

opening, the following controls were added: the percentage

of male competitors and the percentage of White competitors

(at the job posting). Table 6 show the marginal eects for se-

lected coecients of the estimations for dierent models com-

bining the set of characteristics listed above.

The eects attributable to the gender of the applicants as

well as to the gender and racial characteristics of the interview-

ers, although relevant in expected value, do not seem to be sta-

tistically dierent from zero and these results are consistent

across the eight specications. As more controls are incorpo-

rated into the logit regressions, the logarithm of aimed wages

shows a higher eect on hiring, up to the point when it gets

statistically signicant for the last specication. Nonetheless,

the study refrains from interpreting such coecients in an iso-

lated way. The estimators for the eects of having more White

or male competitors are not statistically signicant. As one

would expect that the presence of more White or male compet-

itors in the job search process would aect negatively hiring

chances of an individual, this can be thought of as rst evi-

dence of the lack of discriminatory practices among employ-

ers.

The results shown in Table 6 correspond to the pool of

occupations that were studied (salespersons, secretaries and

assistants). One of these occupations is clearly female-

dominated, so it deserves special attention. Table 6 reports

the equivalent econometric analysis with eight specications

by occupation. Two results deserve special attention. On

one hand, there seems to be a certain positive discrimination

of females among the applicants for salespersons. On the

other handand this is independent of the regression spec-

icationamong applicants for secretarial positions, being

indigenous perfectly predicts failure in getting the job (see

footnote (g) in Table 7). This reveals some sort of discrim-

ination among indigenous females when applying to an

occupation for which the euphemism good presence is

regularly a requisite for the position. It is interesting to

note, however, that interviewer characteristics (including

their race and gender) do not seem to play an important

role on the explanation of the success of failure of

applicants.

13

Applicants

Indigenous

0

100

200

300

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Intensity

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

c

a

s

e

White

0

100

200

300

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Intensity

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

c

a

s

e

Interviewers

Indigenous

0

20

40

60

80

100

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Intensity

N

u

m

e

b

e

r

o

f

c

a

s

e

N

u

m

e

b

e

r

o

f

c

a

s

e

White

0

20

40

60

80

100

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Intensity

Figure 4. Racial intensity distributions of applicants and interviewers. Note: The horizontal axis reects the racial intensity that each individual received. The

intensity varies from an independent score of 010 from an interviewer in each of two categories: White and Indigenous. Zero indicates no physical

characteristics that resembled a specic race and 10 indicating most features of that group.

Table 5. Number of interviewers by race group

Total interviewers

Total Salespersons Secretaries Assistants

Indigenous 83 22 26 31

Mestizo 26 7 5 13

White 93 32 25 33

Total 202 61 56 77

GENDER AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING THROUGH MONITORING INTERMEDIATION SERVICES 321

(b) Race, gender, and aimed wages

One of the questions that the pool of monitors asked the job

applicants, after they knew the position for which they were

applying, and the rms identity and location, was about the

wages they expected to get at the new job. These are not nec-

essarily the wages that they would get if they were oered the

job, nor are they would be their reservation wages; however,

the information about aimed wages provides a good indicator

about expectations in the labor market.

It is possible to think of a situation in which agents in this

system (employers, employees and job seekers) make their

decisions based on the assumption that there is some sort of

statistical discrimination in the market. Then, at the equilib-

rium, it would not be surprising to nd dierences in the dis-

tribution of wages oered by gender and race. The individuals

that belong to a discriminated group, anticipating dierenti-

ated treatment, adjust their beliefs and as a consequence go

on their job search processes by choosing reservation wages

that are below those of the non-discriminated group. On the

other side of the market, employers assume the same prior

common beliefs, and know that individuals from the discrim-

inated groups are willing to accept lower wages. In such a way,

when equilibrium is achieved, the beliefs of the individuals are

conrmed ex-post creating a self-fullling prophecy.

The data obtained from this study enable exploring, at least

partially, some of the complex relationships outlined above.

Information about the individuals wages in their previous jobs

as well as their aimed wages for the jobs for which they were

applying was collected. Table 8 shows the results from regres-

sions for the aimed wages of the individuals on a set of individ-

ual characteristics, including gender and race. With the

purpose of reducing some possible statistical noises, the analy-

sis was restricted to those individuals with no more than 12

months of unemployment and who did not work as self-em-

ployed in their last job. The controls in bold have statistically

signicant impacts in determining aimed wages. The study

found dierences in aimed wages by gender, but not by race.

Males ask for wages that are approximately 7% higher than

those of females, other things held equal. Overall, occupational

experience, college degree, and age of the applicants, as well as

mothers education are important explanatory variables. Those

applying for positions of secretaries and assistants have aimed

wages above than that of those applying for salespersons. Ta-

ble 9 disaggregates the results by occupation and show that

most of the gender dierences in aimed wages occur among

the applicants for salespersons positions. For that group males

tend to ask for wages that are around 16% above than that of

females, other things held equal.

(c) Sensitivity analysis for aimed wages and hiring outcomes

The analysis of previous sections was carried out using the

partition criterion of racial groups with cut-os on the 50th

Table 6. Marginal eects on hiring for all the occupations. Selected coecients

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Mestizo applicant 0.067 0.067 0.067 0.07 0.061 0.062 0.06 0.082

(1.25) (1.28) (1.27) (1.33) (1.15) (1.15) (1.13) (1.66)

White applicant 0.08 0.08 0.071 0.077 0.06 0.062 0.063 0.108

(0.98) (0.99) (0.87) (0.93) (0.75) (0.77) (0.78) (1.18)

Female applicant 0.024 0.024 0.002 0.002 0.008 0.004 0.001 0.004

(0.64) (0.68) (0.04) (0.04) (0.17) (0.08) (0.02) (0.07)

LN last earnings at the main occupation 0.038 0.037 0.035 0.025 0.039 0.035

(1.52) (1.40) (1.18) (0.77) (1.23) (1.05)

LN aimed wages 0.064 0.093 0.081 0.088 0.097 0.126

(1.05) (1.39) (1.21) (1.28) (1.41) (1.94)

% of male competitors 0.058 0.061 0.046 0.047 0.034 0.035

(0.83) (0.88) (0.67) (0.69) (0.53) (0.56)

% of White competitors 0.041 0.059 0.071 0.074 0.052 0.051

(0.50) (0.72) (0.93) (0.97) (0.69) (0.68)

Observations 760 760 732 732 726 721 720 720

Additional controls in the regressions

Occupation type controls Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Interviewer characteristics

a

No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Human capital controls

b

No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Personal characteristics

c

No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes

Labor market experience

d

No No No No No Yes Yes Yes

Firm controls

e

No No No No No No Yes Yes

Applicants family control

f

No No No No No No No Yes

Absolute value of z statistics in parentheses.

Clustered standard errors (at the job posting).

*

Signicant at 5%.

**

Signicant at 1%.

Notes:

a

Interviewer characteristics: race, gender, age, educational level and job experience.

b

Human capital controls: level of education attained by the applicant.

c

Personal characteristics: age, marital status, head of household, migration status.

d

Labor market experience: unemployment spell, occupational status at the time of interview and experience as a self-employed worker.

e

Firm controls: rm size and economic sector of the rm.

f

Applicants family controls: level of education attained by both applicants parents.

322 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

Table 7. Marginal eects on hiring for each occupation. Selected coecients

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Salespersons sample

Mestizo applicant 0.069 0.048 0.028 0.019 0.049 0.002 0.028 0.032

(0.70) (0.64) (0.34) (0.23) (0.42) (0.02) (0.22) (0.24)

White applicant 0.042 0.003 0.029 0.031 0.071 0.04 0.048 0.047

(0.28) (0.03) (0.31) (0.35) (0.96) (0.36) (0.57) (0.57)

Female applicant 0.106 0.064 0.133 0.106 0.099 0.101 0.089 0.08

(1.74) (1.22) (1.82) (1.50) (2.01)

*

(1.95) (2.28)

*

(1.95)

LN last earnings at the main occupation 0.021 0.025 0.004 0.006 0.019 0.008

(0.79) (0.87) (0.20) (0.28) (1.10) (0.39)

LN aimed wages 0.206 0.202 0.114 0.056 0.017 0.045

(2.30)

*

(2.32)

*

(1.77) (0.80) (0.31) (0.65)

% of male competitors 0.076 0.047 0.086 0.09 0.1 0.101

(0.73) (0.46) (1.22) (1.27) (1.72) (1.66)

% of White competitors 0.149 0.095 0.035 0.018 0.046 0.036

(1.33) (0.77) (0.54) (0.26) (0.97) (0.73)

Observations 227 227 214 214 212 211 210 210

Secretaries sample

g

White applicant 0.034 0.044 0.035 0.03 0.004 0.004 0.002 0.035

(0.50) (0.64) (0.50) (0.42) (0.06) (0.05) (0.03) (0.54)

LN last earnings at the main occupation 0.131 0.136 0.142 0.149 0.156 0.116

(1.64) (1.63) (1.80) (1.84) (1.89) (1.44)

LN aimed wages 0.006 0.028 0.051 0.076 0.099 0.162

(0.04) (0.17) (0.32) (0.47) (0.60) (0.97)

% of White competitors 0.1 0.13 0.128 0.147 0.146 0.171

(0.78) (1.01) (1.07) (1.22) (1.20) (1.47)

Observations 177 177 169 169 169 161 161 161

Assistants sample

Mestizo applicant 0.037 0.037 0.032 0.036 0.027 0.039 0.047 0.079

(0.60) (0.57) (0.49) (0.58) (0.42) (0.62) (0.77) (1.61)

White applicant 0.062 0.061 0.049 0.056 0.044 0.061 0.07 0.174

(0.59) (0.57) (0.48) (0.53) (0.43) (0.54) (0.60) (1.23)

Female applicant 0.039 0.044 0.048 0.04 0.022 0.029 0.028 0.021

(1.02) (1.18) (0.79) (0.67) (0.37) (0.46) (0.45) (0.36)

LN last earnings at the main occupation 0.06 0.061 0.053 0.035 0.035 0.028

(1.94) (1.82) (1.50) (0.83) (0.83) (0.64)

LN aimed wages 0.065 0.104 0.096 0.114 0.121 0.176

(0.79) (1.11) (1.07) (1.18) (1.23) (1.98)

*

% of male competitors 0.058 0.046 0.035 0.033 0.041 0.025

(0.83) (0.65) (0.49) (0.46) (0.61) (0.37)

% of White competitors 0.233 0.212 0.223 0.214 0.209 0.216

(1.29) (1.24) (1.28) (1.27) (1.33) (1.40)

Additional controls in the regressions

Interviewer characteristics

a

No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Human capital controls

b

No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Personal characteristics

c

No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes

Labor market experience

d

No No No No No Yes Yes Yes

Firm controls

e

No No No No No No Yes Yes

Applicants family control

f

No No No No No No No Yes

Absolute value of z statistics in parentheses.

Clustered.

*

Signicant at 5%.

**

signicant at 1%.

Notes:

a

Interviewer characteristics: race, gender, age, educational level and job experience.

b

Human capital controls: level of education attained by the applicant.

c

Personal characteristics: age, marital status, head of household, migration status.

d

Labor market experience: unemployment spell, occupational status at the time of interview and experience as a self-employed worker.

e

Firm controls: rm size and economic sector of the rm.

f

Applicants family controls: level of education attained by both applicants parents.

g

Since being indigenous perfectly predicts failure, we calculated this panel of the table using only the sample of Mestizos and Whites, so in this case

Mestizo is the base category.

GENDER AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING THROUGH MONITORING INTERMEDIATION SERVICES 323

percentile. However, there are many other interesting candi-

dates for cut-o values. This sub-section is devoted to the sen-

sitivity analysis. Here the results for aimed wages and hiring

for dierent cut-o points are replicated. The higher (lower)

the cut-o point the more (less) pronounced the racial dier-

ences between the Indigenous and White groups. But at the

same time, the higher (lower) the cut-o points the more likely

it is to have fewer (more) observations in the Indigenous and

White groups. This fact imposes some restrictions on the range

of possible values for cut-o points. For instance, using the

95th percentile as a cut-o value leads to a partition in which

the White group represents only 1% of the sample. On the

other hand, using the 14th percentile as cut-o value leads

to a partition in which there is no individual left within the

White group. For this reason, the sensitivity exercise is carried

out only for a set of possible cut-o points. The interval that

goes from the 15th percentile to the 94th is selected exploring

all possible integer percentiles.

For each possible racial group partition the analysis repli-

cates the hiring regressions reported in Figure 5 (only the last

specication: the one that controls for occupation, labor mar-

ket experience, human capital, personal and familial charac-

teristics of the applicants, as well as rm characteristics).

Figure 5 provides the marginal eect of being Mestizo and that

of being White, computed at the mean (for the pooled sample).

The x-axis of each graph represents the set of possible cut-

o values and the y-axis represents the eect of the corre-

sponding dummy variable on aimed wages. The bold line

shows the average eect while the doted lines illustrate a

95% condence interval for the estimators. The results show

that discriminatory behavior does not prevail in hiring out-

comes for most of the cut-o values. Nonetheless, when fairly

high cut-o values are used, the study nds evidence of statis-

tically dierent hiring outcomes between Indigenous and Mes-

tizos (and also between Indigenous and Whites). Since the

high cut-o values are linked to more pronounced dierences

in racial intensities between the Indigenous and White groups,

ndings in this study suggest that there is some evidence of dis-

crimination only at the extremes of the racial diversity spec-

trum for this sample of job seekers in Lima, Peru. With a

cut-o at the 90th percentile or above, those labeled as White

are about 100% more likely to get a job than those labeled as

Indigenous. Also, individuals labeled as Mestizos are about

30% more likely to get a job than those labeled as Indigenous.

A similar exercise for the aimed wages regression reported in

Table 6 (pooling the three occupations, only the specication

without racegender interactions) was also performed. Fig-

ure 6 shows these results. There are no statistically signicant

dierences in aimed wages among White, Mestizos, and Indig-

enous, except for the partitions at the highest percentiles. In

those cases, White and Mestizo individuals have aimed wages

that are around 20% lower than that of comparable Indige-

nous individuals.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This study explores the role that gender and race play in the

job search and hiring process. This is done by using informa-

tion on real applications and job interviews obtained from the

CIL-PROEMPLEO network, the job intermediation system of

the Ministry of Labor and Employment Promotion in Lima,

Peru. The study analyzes the relative performance in the job

seeking process of comparable individuals of dierent genders

and observable racial characteristics. Applicants for

Table 8. Determinants of the aimed wages

Without

interactions

With

interactions

Mestizo applicant 0.011

(0.31)

White applicant 0.006

(0.14)

Male applicant 0.069

(2.67)

**

Male and Indigenous applicant 0.008

(0.10)

Male and Mestizo applicant 0.023

(0.29)

Male and White applicant 0.067

(0.78)

Female and Mestizo Applicant 0.045

(0.62)

Female and White Applicant 0.048

(0.66)

Human capital controls

Incomplete non-college post-secondary studies 0.01 0.01

(0.31) (0.31)

Non-college post-secondary degree 0.042 0.043

(1.60) (1.66)

Incomplete college studies 0.013 0.014

(0.48) (0.50)

College degree 0.162 0.163

(5.83)

**

(5.85)

**

Personal characteristics

Age 0.059 0.058

(4.35)

**

(4.24)

**

Age^2 0.001 0.001

(3.60)

**

(3.54)

**

Single 0.018 0.017

(0.77) (0.73)

Household head 0.003 0

(0.10) (0.02)

Applicants family controls

Mother has a high-school degree 0.058 0.059

(3.43)

**

(3.47)

**

Mother has a non-college post-secondary degree 0 0

0.00 (0.02)

Mother has a college degree 0.04 0.04

(1.00) (0.96)

Labor market experience

Occupational experience 0.036 0.036

(4.11)

**

(4.01)

**

Occupational experienced 0.002 0.002

(3.46)

**

(3.33)

**

Unemployment spell (top-coded at 12 months) 0.001 0.001

(0.14) (0.20)

Was red from his last job 0.278 0.242

(5.44)

**

(3.62)

**

Quit from his last job 0.243 0.204

Left his last job for other reasons 0.225 0.187

(4.77)

**

(2.75)

**

Had a job at the moment of the application 0.014 0.011

(0.20) (0.15)

Worked as a dependant during the last 12 months 0.05 0.048

(1.21) (1.15)

Occupation type controls

Occupation (secretaries) 0.171 0.175

(5.73)

**

(5.85)

**

Occupation (assistants) 0.144 0.147

(4.91)

**

(4.95)

**

Constant 4.901 4.987

(23.73)

**

(21.18)

**

Observations 736 736

R-squared 0.39 0.39

Robust t statistics in parentheses.

*

Signicant at 5%.

**

Signicant at 1%.

324 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

Table 9. Determinants of the aimed wages for each occupation

Salespersons Secretaries Assistants

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Mestizo applicant 0.003 0.095 0.036

(0.06) (0.78) (0.75)

White applicant 0.007 0.115 0.019

(0.14) (0.93) (0.34)

Male applicant 0.152 0.001

(5.93)

**

(0.04)

Male and Indigenous applicant 0.132 0.127

(1.76) (1.16)

Male and Mestizo applicant 0.145 0.102

(2.54)

*

(0.97)

Male and White applicant 0.135 0.179

(1.59) (1.24)

Female and Mestizo applicant 0.014 0.118

(0.21) (1.08)

Female and White applicant 0.001 0.087

(0.02) (0.80)

Human capital controls

Incomplete non-college post-

secondary studies

0.005 0.007 0.074 0.001 0.024

(0.11) (0.15) (1.14) (0.00) (0.10)

Non-college post-secondary

degree

0.049 0.053 0.015 0.17 0.175

(0.83) (0.93) (0.33) (3.03)

**

(2.93)

**

Incomplete college studies 0.037 0.037 0.086 0.023 0.024

(0.84) (0.83) (1.34) (0.38) (0.37)

College degree 0.156 0.155 0.057 0.076 0.07

(2.15)

*

(2.11)

*

(0.64) (1.51) (1.35)

Personal characteristics

Age 0.037 0.037 0.052 0.072 0.073

(0.92) (0.91) (2.66)

*

(1.54) (1.57)

0 0 0.001 0.001 0.001

Age^2 (0.71) (0.71) (2.34)

*

(1.20) (1.29)

0.037 0.036 0.019 0.04 0.044

Single (1.01) (0.95) (0.39) (0.77) (0.81)

Household head 0.048 0.046 0.115 0.046 0.04

(0.90) (0.88) (2.73)

**

(1.34) (1.15)

Applicants family controls

Mother has a high-school degree 0.046 0.048 0.076 0.066 0.07

(2.09)

*

(2.24)

*

(2.40)

*

(2.18)

*

(2.39)

*

Mother has a non-college post-

secondary degree

0.112 0.116 0.054 0.041 0.042

(2.27)

*

(2.31)

*

(1.24) (0.93) (0.95)

Mother has a college degree 0.13 0.134 0.156 0.036 0.037

(3.07)

**

(3.15)

**

(2.19)

*

(0.57) (0.59)

Labor market experience

Occupational experience 0.048 0.048 0.008 0.014 0.017

(3.32)

**

(3.35)

**

(0.39) (1.11) (1.37)

Occupational experience^2 0.004 0.004 0 0 0

(3.32)

**

(3.36)

**

(0.24) (0.66) (0.69)

Unemployment spell (top-coded

at 12 months)

0.009 0.009 0.007 0.013 0.014

(1.55) (1.55) (1.02) (2.01)

*

(2.08)

*

Was red from his last job 0 0 0.052 0.38 0.463

(.) (.) (0.91) (4.12)

**

(3.74)

**

Quit from his last job 0.054 0.054 0.012 0.336 0.415

(1.33) (1.30) (0.23) (4.56)

**

(3.72)

**

Left his last job because the

contract nished

0.031 0.029 0.016 0.329 0.41

(0.55) (0.53) (0.29) (4.96)

**

(3.87)

**

Left his last job for other reasons 0.055 0.053 0 0.315 0.403

(continued on next page)

GENDER AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING THROUGH MONITORING INTERMEDIATION SERVICES 325

accounting and administrative assistants, salespersons, and

secretaries were the focus of this study. The racial heterogene-

ity of the sample enabled grouping of individuals into three ra-

cial categories: White, Mestizo, and Indigenous. The creation

of these groups was based on a cut-o criterion.

Inspired by audit studies, this paper controls for dier-

ences in observable characteristics in a detailed way, not

only during the eldwork through the formation of the

groups of applicants per job posting, but also in the econo-

metric models. However, as in most natural eld experi-

ments, these gains come at a cost: external validity. One

has to be cautious before trying to extrapolate the ndings

of this study to the whole Peruvian, or even Limenian, labor

markets. Nonetheless, the ndings are interesting, thought

provoking, and consistent with a story of discriminatory

outcomes that arise as a result of information failures.

This study led to two sets of ndings: one regarding hiring

outcomes and the other on expectations of applicants. First,

the study found evidence of dierences in treatment based

on gender and based on racial characteristics, but only when

using the partition criterion that compared groups with great-

er dierences in observable racial characteristics. Mestizos

seem to perform better in the segment of the labor market

studied here. In terms of specic occupations analyzed in

Table 9Continued

Salespersons Secretaries Assistants

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

(1.76) (1.62) (.) (4.23)

**

(3.36)

**

Had a job at the moment of the application 0.128 0.129 0.139 0.08 0.06

(1.14) (1.16) (1.01) (0.64) (0.47)

Worked as a dependant during the last 12 months 0.112 0.114 0.044 0.147 0.137

(1.60) (1.66) (0.63) (2.20)

*

(1.99)

Constant 5.317 5.325 5.474 5.002 4.999

(9.61)

**

(9.73)

**

(15.15)

**

(7.10)

**

(6.83)

**

Observations 213 213 178 345 345

R-squared 0.43 0.43 0.22 0.35 0.35

Robust t statistics in parentheses.

Clustered standard errors (at the posting).

*

Signicant at 5%.

**

Signicant at 1%.

Mestizo Applicant

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Cut-off Value

White Applicant

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Cut-off Value

Figure 5. Marginal eects on hiring for dierent cut-o values.

326 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

metropolitan Lima, there was evidence of positive discrimina-

tion for females in salespersons occupations (although not

robust to all specications) and negative discrimination for

indigenous females when applying to secretarial positions

(with the basic partition criterion, being indigenous perfectly

predicted a failure in the hiring regressions). Second, the study

found gender dierences in expectations, measured by aimed

wages. When job applicants were asked, How much would

you like to earn in the position for which you are applying?,

females responses were on average 7% below those of compa-

rable males, after controlling for a rich set of observable char-

acteristics of the applicants and the rms. Even though, there

were no dierences in wage expectations according to dierent

racial groups.

NOTES

1. This index is interpreted as the minimum percentage of individuals of

one of the comparing groups that should change their occupations in

order to equalize the distributions of individuals across occupations for

both groups. See Fluckiger and Silber (1999) for a detailed description of

the segregation measures, including the Duncan Index.

2. These groups are: Professionals and Technicians, Managers, Admin-

istrative Personnel, Merchants and Salespersons, Service Workers, Agri-

cultural Workers and Non-Agricultural Workers.

3. In this case, a non-segregated work force is dened as a situation in

which the distributions of males and females across occupations are the

same.

4. Mestizo is a term that refers to those of mixed race and hence is

not considered as one of the basic dimensions.

5. The literature on audit studies is vast. See Riach and Rich (2002) for

an interesting survey of this literature in dierent market settings. Also

refer to Goldin and Rouse (2000) on the impact of blind auditions.

6. See Heckman (1993, 1998) and Heckman and Siegelman (1993) for a

critical description of the results from a detailed analysis of the

identication assumptions behind the audit study model.

7. CIL stands for Centro de Intermediacion Laboral (Center of Job

Intermediation) for further details see (http://www.sil.org.pe).

8. In addition, to validate the pollsters racial scores, a random sample

was taken from the pool of applicants. The pictures of these individuals

were independently scrutinized by three other equally-trained pollsters.

The score comparison of the original pollsters and the control pollsters

showed no dierences.

9. However, all these advantages come at a cost: selection. On one hand,

the rms and job seekers participating at the intermediation service could

be a non-random sample of the population; and on the other hand, the job

seekers send to the nal job interview could be a non-random sample of all

the applicants. While the rst type of selection somewhat limits the

external validity of our results, the second type of selection can not happen

because the public intermediation system is explicitly prohibited (by law)

to perform any type of discrimination.

Mestizo Applicant

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Cut-off Value

M

a

r

g

i

n

a

l

E

f

f

e

c

t

White Applicant

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Cutt-off Value

M

a

r

g

i

n

a

l

E

f

f

e

c

t

Figure 6. Marginal eects on aimed wages for dierent cut-o values.

GENDER AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING THROUGH MONITORING INTERMEDIATION SERVICES 327

10. Initially, data-entry assistants were also considered for selection, but

the number of posted job openings into the system was too small to be

considered.

11. This is related in the fact that the public and private institutions that

this segment of the population typically attend have similar qualities.

Graduates from elite universities do not use the services of PROEMPLEO

in their job search processes.

12. The standard errors for these success rates are 2.3%, 3.0%, and 2.0%

for salespersons, secretaries, and assistants, respectively.

13. In other specications, we also included interactions of the appli-

cants and interviewers gender and racial characteristics and found no

signicant coecients in the hiring regressions.

REFERENCES

Bertrand, Marianne, & Mullainathan, Sendhil (2004). Are Emily and Greg

more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A eld experiment on labor

market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 9911013.

Blau, Francine, & Ferber, Marianne (1992). The economics of women, men

and work (2nd ed.). Englewood Clis, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Coate, Stephen, & Loury, Glenn (1993). Will armative-action policies

eliminate negative stereotypes?. American Economic Review, 83(5),

12201240.

Deutsch, Ruthanne, Morrison, Andrew, Piras, Claudia, & N

opo, Hugo

(2002). Working within connes: Occupational segregation by gender in

three Latin American countries (Inter-American Development Bank

Sustainable Development Department Technical Papers Series No. 126).

Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Fluckiger, Yves, & Silber, J. (1999). The measurement of segregation in the

labor force. Heidelberg, NY: Physica-Verlag.

Goldin, Claudia, & Rouse, Cecilia (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: The

impact of blind auditions on female musicians. American Economic

Review, 90(4), 715741.

Harrison, Glenn, & List, John A. (2004). Field experiments. Journal of

Economic Literature, 42(4), 10091055.

Heckman, James (1998). Detecting discrimination. The Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 12(2), 101116.

Heckman, James, & Siegelman, Peter (1993). The urban institute audit

studies: Their methods and ndings. In M. Fix, & R. Struyk (Eds.),

Clear and Convincing Evidence: Measure of Discrimination in America.

Washington DC: The Urban Institute Press.

Lindzey, G., & Aronson, E. (1975). The handbook of social psychology, Vol

2 (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

N

opo, Hugo, Saavedra, Jaime, & Torero, Maximo (2007). Ethnicity and

earnings in a mixed race labor market. Economic Development and

Cultural Change, 55(4).

Riach, Peter, & Rich, Judith (2002). Field experiments of discrimination in

the marketplace. The Economic Journal, 112, F480F518.

Rosenthal, R. (1976). Experimenter eects in behavioral research (2nd ed).

New York, NY: Irvington Publishers.

Torero, Maximo, Saavedra, Jaime, N

opo, Hugo, & Escobal, Javier

(2004). An invisible wall. The economics of social exclusion in Peru.

In Mayra Buvinic, et al. (Eds.), Social inclusion and economic

development in Latin America. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins

University Press.

van Beek, Krijn, Koopmans, Carl, & van Praag, Bernrd (1997). Shopping

at the labor market: A real tale of ction. European Economic Review,

41, 295317.

Yinger, John (1998). Evidence on discrimination in consumer markets.

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(2), 2340.

Zegers de Beijl, Roger (Ed.) (2000). Documenting discrimination against

migrant workers in the labour market: A comparative study of four

European countries. Geneva: International Labour Oce.

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

328 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

You might also like

- Discrimination Against Women's Wages: Assaults and Insults on WomenFrom EverandDiscrimination Against Women's Wages: Assaults and Insults on WomenNo ratings yet

- Sources of Gender Wage Gaps For Skilled Workers in Latin American CountriesDocument25 pagesSources of Gender Wage Gaps For Skilled Workers in Latin American CountriesMedardo AnibalNo ratings yet

- Critical race theory and inequality in the labour market: Racial stratification in IrelandFrom EverandCritical race theory and inequality in the labour market: Racial stratification in IrelandNo ratings yet

- Wage Discrimination When Identity Is Subjective: Evidence From Changes in Employer-Reported RaceDocument37 pagesWage Discrimination When Identity Is Subjective: Evidence From Changes in Employer-Reported RacetiraNo ratings yet

- Addressing Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in Human Services: Multisystemic ApproachesFrom EverandAddressing Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in Human Services: Multisystemic ApproachesNo ratings yet

- Gender and Racial Wage Gaps in Brazil 19Document39 pagesGender and Racial Wage Gaps in Brazil 19Ana DanielleNo ratings yet

- Racism, Class and Gender EssayDocument13 pagesRacism, Class and Gender EssayAli UsamaNo ratings yet

- Borowczyk Martins2017Document78 pagesBorowczyk Martins2017NGUYỄN LINHNo ratings yet

- Discrimination Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesDiscrimination Literature Reviewaflsmperk100% (1)

- Explaining The RegionalDocument10 pagesExplaining The Regionalryry1993No ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Job Attribute Prefe-Rences and Job ChoiceDocument11 pagesGender Differences in Job Attribute Prefe-Rences and Job Choiceani ni musNo ratings yet

- Peoples Kitchens Peru Thorp Working Paper 67Document20 pagesPeoples Kitchens Peru Thorp Working Paper 67gottsundaNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural MotivationDocument7 pagesCross-Cultural MotivationNurjis AzkarNo ratings yet

- The Persistence of Gender Segregation at Work (2011)Document17 pagesThe Persistence of Gender Segregation at Work (2011)pampeedooNo ratings yet

- Discrimination, Women, and Work: Processes and Variations by Race and ClassDocument24 pagesDiscrimination, Women, and Work: Processes and Variations by Race and ClassDeb DasNo ratings yet

- Zschirnt Ruedin 2016 Meta Post PrintDocument22 pagesZschirnt Ruedin 2016 Meta Post PrintANo ratings yet

- Neal, Derek. JPE (2004) PDFDocument29 pagesNeal, Derek. JPE (2004) PDFwololo7No ratings yet

- CXY ReportDocument21 pagesCXY ReportHezekia KiruiNo ratings yet

- Researching Race in ChileDocument16 pagesResearching Race in Chilecrema241No ratings yet

- DiscriminationDocument45 pagesDiscriminationCristina FratilaNo ratings yet

- What Job Would You Apply To?: Findings On The Impact of Language On Job SearchesDocument48 pagesWhat Job Would You Apply To?: Findings On The Impact of Language On Job SearchesRose Mary Molina NuñezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3, 4 & 5Document3 pagesChapter 3, 4 & 5Hezekia KiruiNo ratings yet

- WDR2013 BP Inequality of Opportunities in The Labor Market (2016!12!11 23-51-45 UTC)Document40 pagesWDR2013 BP Inequality of Opportunities in The Labor Market (2016!12!11 23-51-45 UTC)michelmboueNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Racial DiscriminationDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Racial Discriminationea0kvft0100% (1)

- Bias in Terms of Culture and A Method For ReducingDocument21 pagesBias in Terms of Culture and A Method For ReducingMaryam KhanzaiNo ratings yet

- Work Discrimination and Unemployment in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesWork Discrimination and Unemployment in The PhilippinesJoshua TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Gender and SexualityDocument7 pagesGender and SexualityTingjin LesaNo ratings yet

- Inequality in Wages and Role of Gender in ItDocument7 pagesInequality in Wages and Role of Gender in ItIshika KumarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Racial Discrimination in The WorkplaceDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Racial Discrimination in The WorkplaceissyeasifNo ratings yet

- Gender EqualityDocument29 pagesGender EqualitylolalelaNo ratings yet

- Explaining UnemploymentDocument34 pagesExplaining UnemploymentApik Siv LotdNo ratings yet

- The Gender Wage Gap Extent, Trends, and Explanations - Jel.20160995Document121 pagesThe Gender Wage Gap Extent, Trends, and Explanations - Jel.20160995daskirNo ratings yet

- Racial Discrimination in The WorkplaceDocument3 pagesRacial Discrimination in The WorkplaceNatasha Kate LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Theoretical BackgroundDocument7 pagesTheoretical BackgroundRetarded EditsNo ratings yet

- Now ServingDocument15 pagesNow Servingmeghang1217No ratings yet

- Gender Discrimination in The Workplace A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesGender Discrimination in The Workplace A Literature ReviewbqvlqjugfNo ratings yet