Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In Memory of Keerthi Balasooriya

Uploaded by

Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In Memory of Keerthi Balasooriya

Uploaded by

Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraCopyright:

Available Formats

World Socialist Web Site wsws.

org

In Memory of Keerthi Balasuriya

By David North

18 December 2012

This article was originally posted on the WSWS in two parts on

December 18-19, 2007.

It is with profound respect and a continuing sense of loss that the

International Committee of the Fourth International marks today the 20th

anniversary of the sudden and terribly premature death of Keerthi

Balasuriya. Even after the passage of so many years, for all those who

knew and worked with Comrade Keerthi the sense of political and

personal loss remains acute.

His death on the morning of December 18, 1987, while at work in the

offices of the Sri Lankan Revolutionary Communist League (predecessor

of the Socialist Equality Party), came without any warning. Less than one

month had passed since he had returned from Europe, where he had

attended a meeting of the International Committee. Keerthi was at his

desk, writing a statement on the political lessons of the 1985-86 split in

the ICFI, when he suffered a fatal heart attack. He was only 39. Comrade

Keerthi, had he lived, would only now be looking forward to his 60th

birthday.

But for all that we lost with his premature death, Comrade Keerthi left

behind a substantial and enduring legacy of political work that constitutes

an essential foundation of the world Trotskyist movement.

Notwithstanding the immense political and economic changes of the

past two decades, the issues and problems with which Keerthi grappled

remain no less urgent and relevant today than they were at the time of his

death.

Keerthi was born on November 4, 1948, little more than one year after

both India and Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was called until 1972) acquired state

independence on the basis of squalid deals between British imperialism

and the national bourgeoisie of the subcontinent. In different ways, the

settlements reached between the Indian and Ceylonese national

bourgeoisie on the one hand and imperialism on the other set the stage for

all the political tragedies that were to unfold over the next six decades.

These settlements demonstrated that the national bourgeoisie of India

and Ceylon feared social revolution far more than they desired genuine

independence. Gandhi and Nehru accepted the partition of India along

religious lines, a betrayal of the democratic and social aspirations of the

masses that has cost the lives of millions, condemned the subcontinent to

recurrent wars, and consolidated the grip of imperialism over the region.

In Ceylon, the independence fashioned by the national bourgeoisie

institutionalized systematic discrimination against the Tamil minority and

sowed the seeds of the future civil war.

The betrayal of the independence struggle by the national bourgeoisie

vindicated the central tenets of Trotskys theory of permanent revolution,

which insisted that the historically progressive tasks of the democratic

anti-imperialistic struggle could be achieved only through the conquest of

power by the working class, led by a Marxist party based on an

internationalist and socialist program.

In fact, in the aftermath of the formal transfer of power to the Indian and

Ceylonese bourgeoisie, the principles of the theory of permanent

revolution were invoked by the leaders of the Ceylonese Trotskyist

movement, who condemned the terms upon which independence was

achieved. However, over the following decade, the Lanka Sama Samaja

Party (LSSP)the Trotskyist partydrifted steadily to the right.

While this process developed in response to the pressures of the national

environment, which encouraged all sorts of opportunist adaptations in the

pursuit of parliamentary gains, a key factor in the degeneration of the

LSSP was the general growth of revisionist tendencies inside the Fourth

International. Led by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel, these forces

systematically covered up for and even encouraged the opportunist

orientation of the LSSP.

The protracted political degeneration reached its climax in 1964, when

the LSSP, which still enjoyed a mass following in the working class,

agreed to join the crisis-ridden bourgeois government of Madam

Bandaranaike. This was a turning point in the history both of Ceylon and

the Fourth International. In the case of the latter, the entry of the LSSP

into a reactionary political coalition with the bourgeoisie exposed the

counter-revolutionary nature of Pabloite revisionism. For Ceylon, the

formation of the coalition set into motion the process that led inexorably,

within less than 20 years, to the eruption of civil war.

Keerthi Balasuriyas education consisted above all in assimilating the

political lessons of these experiences. The International Committee played

the central role in this process. Having been formed as a product of the

political struggle against Pablo and Mandel which erupted inside the

Fourth International in 1953, the International Committee had followed

developments in Ceylon and drawn attention to the increasingly

opportunist course of the LSSP.

In the aftermath of the LSSPs entry into coalition, the British

Trotskyists under the leadership of Gerry Healy mounted a political

offensive against the LSSP that found a response among the best sections

of the Trotskyist student youth in Ceylon. The work of political

clarification, which spanned several years, led to the formation of the

Revolutionary Communist League in 1968. Keerthi was elected to the

post of general secretary.

It did not take long before the RCL and Comrade Keerthi confronted a

major political test. The treachery of the LSSP weakened the working

class movement, helped split the peasantry from the workers, created

immense political confusion and created a climate favorable for the

growth of Maoist influence among significant sections of the peasant and

student youth. This led to the formation and rapid growth of the JVP

(Janatha Vimukthi PeramunaPeoples Liberation Front).

This organization projected an image of ferocious anti-imperialist

militancy. It required both political courage and Marxist perspicacity to

detect and expose the essentially petty-bourgeois and reactionary political

perspective concealed within the revolutionary rhetoric of the JVP.

In 1970, Keerthi wrote The Class Nature and Politics of the JVP, which

clearly established the petty-bourgeois and anti-Marxist character of this

organization. Its leader, Wijeweera, threatened that Keerthi would be

hanged when the JVP came to power.

But in 1971, the coalition government launched a ferocious wave of

repression against the JVP and its supporters among the rural youth.

Notwithstanding its irreconcilable differences with the JVP, the RCL

launched a campaign against the governments repression. Even the JVP

was compelled to acknowledge the principled character of the RCLs

World Socialist Web Site

politics. After his release from prison, Wijeweera personally went to the

headquarters of the RCL to express his appreciation of the partys

campaign. (This did not prevent the JVP from launching attacks against

RCL cadre in the late 1980s.)

An even more significant demonstration of Keerthis political firmness

and strength of character was shown in his criticism of the position taken

by the British Trotskyists of the Socialist Labour League in support of

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhis decision to send troops into East

Pakistan, supposedly in support of the Bengali liberation movement. A

statement written by Michael Banda of the SLL (predecessor of the

Workers Revolutionary Party), published on December 6, 1971, declared,

We critically support the decision of the Indian bourgeois government to

give military and economic aid to Bangladesh.

The position adopted by the RCL was diametrically opposed to that of

the SLL. An RCL statement published on December 8, 1971 declared:

The Trotskyist movement, representing the revolutionary interests of the

proletariat, defines its position in relation to all these movements,

struggles and conflicts from the standpoint of the proletarian struggle for

socialism. It declares emphatically and unequivocally that the task of the

proletariat is not that of supporting any one of the warring factions of the

bourgeoisie, but that of utilizing each and every conflict in the camp of

the class enemy for the seizure of power with the perspective of setting up

a federated socialist republic which alone would be able to satisfy the

social and national aspirations of the millions of toilers in the

subcontinent.

Lacking the type of instantaneous communications that exist today, the

RCL was not aware of the SLLs position when it published its own

statement. When the SLL statement arrived in Colombo, Keerthi

instructed that the RCL immediately withdraw its own position from

public circulation. He did so because, as he wrote to Cliff Slaughter, the

secretary of the ICFI, clarity inside the international is more important

than anything else and it is impossible for us to build a national section

without fighting to build the international. However, in explaining the

RCLs disagreement with the SLL, Keerthi did not mince words in his

December 16, 1971 letter to Slaughter:

It is not possible to support the national liberation struggle of the

Bengali people and the voluntary unification of India on socialist

foundations without opposing the Indo-Pakistan War. Without opposing

the war from within India and Pakistan it is completely absurd to talk

about a unified socialist India which alone can safeguard the right of

self-determination of the many nations in the Indian subcontinent.

On January 11, 1972, Keerthi dispatched another letter to London, this

time in reply to Mike Bandas enthusiastic support for Gandhis

intervention. He detected in Bandas position a retreat from the Trotskyist

principles which previously had been defended by the ICFI against the

Pabloites.

The logic of the false political position of the IC on Bangladesh would

have and has led to the abandonment of all the past experiences of the

Marxist movement regarding the struggle of the colonial masses. Now it

is evident that these attempts are tending to move in the direction of

revising all the capital gains made by the SLL leadership in the fight

against the SWP during the 1961-63 period. Your December 27 letter was

nothing more than an attempt to defend a political position which

completely breaks with Marxism. By attempting to defend it you have

distorted Marxism, drowned yourself in confusion and exposed your

political bankruptcy.

Keerthis prescient letters were not circulated within the International

Committee by the Socialist Labour League. Realizing that the RCL was

capable of adopting an independent and critical attitude to the work of the

ICFI, the Socialist Labour League set out to isolate the Sri Lankan

Trotskyists and Comrade Keerthi.

The more the SLL (and then the WRP) drifted to the right, the more

pernicious and ruthless the efforts to isolate the RCL became. It was not

until the eruption of the political crisis within the British organization and

the International Committee in 1985 that it became possible for these

valuable letters to find an audience within the International movement.

The impressionistic response of the Socialist Labour League to the

Indian governments military intervention in East Pakistan and its

vindictive reaction to the Revolutionary Communist Leagues criticisms

reflected a deepening political crisis within the British organization. It

was hardly an accident that Michael Banda had emerged as the

spokesman for the SLLs endorsement of the Indian governments

policies. For several years he had been expressing doubt about the

relevance of Trotskys theory of permanent revolution, which insisted

upon the central and decisive revolutionary role of the working class in

the struggle against imperialism.

Had not the victory of Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, Mao Zedong in China,

and even Tito in Yugoslavia demonstrated the possibility of alternative

paths to socialism, based on the armed struggle of the peasantry? For

Banda, Prime Minister Indira Gandhis intervention in East Pakistan, an

action which antagonized the Nixon administration, was yet another form

of anti-imperialist struggle. It demonstrated, in Bandas view, that the

national bourgeoisie in Asia was capable of revolutionary initiatives

which contradicted Trotskys perspective.

Fearful of the organizational disruption that might result from an open

conflict within the SLL leadership over basic programmatic issues, Gerry

Healy, the principal leader of the British section, sought to avoid a

discussion of the political differences. Moreover, Banda was hardly alone

in his doubts about the viability of the Trotskyist perspective. In the 1960s

the political radicalization of significant sections of the petty bourgeoisie

had substantially increased the social constituency for the sort of

revisionist politics that had been pioneered by Pablo and Mandel. The

SLL itself had benefited organizationally from the radicalization of

student youth. To the extent that the SLL retreated from its earlier

intransigence on essential questions of revolutionary program and

perspective, newly radicalized youth and other elements from the petty

bourgeoisie entered the British movement without undergoing the

necessary education in the history and principles of the Fourth

International. This danger was compounded by the fact that the politically

influential strata of professional academics who played a major role in the

theoretical and educational work of the SLL was particularly susceptible

to the lure of various forms of petty-bourgeois revisions of Marxism.

It was in this increasingly murky political environment that the SLL

leadership rationalized its evasion of the struggle for programmatic clarity

by arguing that agreement on philosophical method was far more

important. Indeed, in an astonishing redefinition of the approach that the

Trotskyist movement had taken throughout its history, Healy and his

principal advisor on matters theoretical, Cliff Slaughter, began to argue

that the very discussion of program was a real impediment to the

development of dialectical thought! And so there appeared in the

documents of the International Committee the claim, authored by

Slaughter, that the experience of building the revolutionary party in

Britain had demonstrated that a thoroughgoing and difficult struggle

against idealist ways of thinking was necessary which went much deeper

than questions of agreement on program and policy. [ Trotskyism Versus

Revisionism, Vol. 6, London, 1975, p. 83.]

Healy may not have clearly understood (though Professor Cliff

Slaughter certainly did) that the type of separation of the struggle for

Marxist theory from the development of the revolutionary perspective of

the working class advocated in this and similar formulations represented a

dangerous political and theoretical capitulation to conceptions that were

wildly popular in the petty-bourgeois milieu of the anti-Marxist New Left.

But however Healy rationalized his position in his own mind, the new

theoretical arguments both reflected and encouraged skepticism about the

World Socialist Web Site

historic role of the Fourth International.

As Slaughter wrote in 1972: Will revolutionary parties, able to lead the

working class to power and the building of socialism, be built simply by

bringing the program, the existing forces of Trotskyism, onto the scene of

political developments caused by the crisis? Or will it not be necessary to

conduct a conscious struggle for theory, for the negation of all the past

experience and theory of the movement into the transformed reality of the

class struggle. [Ibid, p. 226]

It is only necessary to strip this passage of its rhetorical form and

deconstruct its pretentious pseudo-philosophical syntax, so beloved of

petty-bourgeois academics, to expose the two distinctly revisionist and

politically liquidationist positions that were being advanced by Slaughter:

1) The Trotskyist movement, based on the historically developed program

of the Fourth International, would not be able to lead the working class to

power; and 2) The transformed reality of the class struggle [a favorite

Pabloite phrase] required a conscious struggle for theory , which

consisted of the negation [i.e., the junking] of all the past experience

and theory of the movement.

For Healy, Banda and Slaughter, these formulations were not merely a

matter for abstract debate. As the 1970s unfolded, they sought to

implement them with a vengeance. Increasingly dismissive of the

programmatic heritage of Trotskyism, the SLL became hostile to the

sections of the International Committee of the Fourth International [the

existing forces of Trotskyism] and began to search for other political

forces with whom new alliances could be constructed. These were

eventually to be found in national movements and regimes in the Middle

East.

This right-wing shift in the politics of the SLL (which became the

Workers Revolutionary Party in November 1973) underlay the deepening

isolation of Keerthi Balasuriya and the Revolutionary Communist League

within the International Committee. The RCLs criticisms of the SLL

response to the Indo-Pak War of 1971 were taken by Healy, Banda and

Slaughter, quite correctly, as an indication that the Ceylonese/Sri Lankan

section would not go along with their abandonment of Trotskyist politics.

Despite the extremely difficult conditions under which the Sri Lankan

comrades conducted their work, which were worsened by the fact that

they were denied any semblance of fraternal support and collaboration

within the ICFI, the RCL continued to defend the principles of

Trotskyism. Particularly noteworthy in this regard was the partys

response to government-instigated anti-Tamil pogroms that broke out in

Colombo in July 1983. In the face of brutal repressive measures, the RCL

spoke out fearlessly in opposition to the anti-Tamil campaign.

Even under these dangerous conditions, the RCL received no support

from the international movement, which remained under the control of the

Workers Revolutionary Party. The WRP actually posted a statement in its

newspaper, written by Michael Banda, which noted in passing that It is

possible, even probable, that the police and army [in Sri Lanka] have used

the arbitrary and uncontrolled powers granted to them under the

emergency laws to kill our comrades and destroy their press. However,

the statement issued neither a condemnation of this persecution nor a call

for an international campaign for the defense of the Revolutionary

Communist League.

* * *

The Workers Revolutionary Party took care not to inform the

Revolutionary Communist League of the serious theoretical and political

criticisms raised by the Workers League between October 1982 and

February 1984. In January 1984, the Political Committee of the Workers

League specifically requested that Comrade Keerthi be invited to London

to attend a meeting of the ICFI at which new criticisms of the political

line of the Workers Revolutionary Party were to be discussed.

However, when I arrived in London, I was told by Michael Banda that it

had not been possible to establish contact with the Sri Lankan comrades

and, therefore, Keerthi would not be present at the meeting. Bandas

gross lie demonstrated the lengths to which the WRP leadership was

prepared to go in order to prevent a principled discussion of political

differences within the International Committee. In fact, Healy, Banda and

Slaughter had simply decided among themselves not to inform the RCL of

the scheduled meeting.

However, the eruption of a dirty scandal and intense organizational

crisis within the WRP, the culmination of more than a decade of

opportunism, made it impossible for the WRP leaders to continue to block

political discussion within the International Committee. In late October

1985, Keerthi, with the assistance of the Australian section, flew to

London. Upon his arrival, he was almost immediately called into the

office of Michael Banda, who proceeded to regale him at great length

with the salacious details of the sexual scandal involving Healy. When

Banda had finally exhausted himself, Keerthi asked: What precisely,

Comrade Mike, are your political differences with Gerry Healy? The

question seemed to catch Banda off balance. Unable to formulate an

answer of his own, Banda handed Keerthi a copy of the report that I had

given to the ICFI meeting in February 1984, which consisted of a detailed

criticism of the political line of the Workers Revolutionary Party.

On Sunday morning, October 20, 1985, I received a call from Banda

informing me that a statement was about to be published in the Newsline,

the WRP newspaper, announcing the expulsion of Healy. This decision

had been taken without any discussion within the International

Committee. Almost as an afterthought Banda told me that Keerthi and

Nick Beams, the secretary of the Australian section, were in London.

Were they available to speak to me, I asked? Bandas evasive answer

quickly convinced me that there was no use pursuing the matter with him.

After hanging up, I called the offices of the WRP on another line and

asked to speak to Nick and Keerthi. When Keerthi came to the phone, he

stated at once, I have read your political criticisms, and am in agreement

with them. Nick, Keerthi and I agreed that it was necessary to discuss the

political issues raised by the crisis that had broken out in the WRP and

develop a unified response within the International Committee. That

evening I flew to London. Though I had known Keerthi since the early

1970s, it was only with the outbreak of the struggle within the ICFI that

my political collaboration with this extraordinary man really began.

The political struggle that unfolded in the weeks and months that

followed marked a turning point in the history of the Fourth International.

The source of the political strength that has been demonstrated by the

International Committee during the past two decades of tumultuous

upheavals is to be found in the high level of theoretical clarity and

programmatic agreement achieved on the basis of the detailed analysis of

the crisis and break-up of the Workers Revolutionary Party. It is not an

exaggeration to state that there is not another struggle within the history

of the Trotskyist movement in which the political and theoretical issues

underlying the split were analyzed in such depth and detail.

The role played by Keerthi during this period was of an absolutely

critical character. His vast knowledge of the history of the revolutionary

socialist movement was combined with an exceptional capacity for

political analysis. Poring over the political statements produced by the

WRP between 1973 and 1985, Keerthi would discover those critical

passages in which he detected a retreat from Marxism. The significance of

the passage upon which Keerthi had focused was not always immediately

apparent. He would then rephrase it, and begin to expound on its practical

implications.

These insights would be supplemented by references to the history of

the Marxist movement. As the discussion unfolded, it became clear that

more was involved than the scoring of an additional polemical point.

Keerthi was engaged in the elaboration of a comprehensive critique of the

theory and practice of the political opportunism associated with the

conceptions of Pablo and Mandel that had wreaked havoc inside the

World Socialist Web Site

Fourth International.

The essential conclusion of this critique was summed up in an editorial

published in the Fourth International, the theoretical journal of the ICFI,

in March 1987:

Thus the revisionism that attacked the Fourth International after

World War II was a class phenomenon which reflected the changing

political needs of imperialism itself. Confronted with the emergence

of proletarian revolution, imperialism had to open up possibilities for

new layers of the middle classes to assume the role of a buffer

between its interests and that of the proletariat. Pabloite revisionism

translated these basic needs of imperialism and the class interests of

the petty bourgeoisie into those vital theoretical formulae which

justified the adaptation of the Trotskyist movement to these forces. It

pandered to the futile illusion that the petty bourgeoisie, through its

control of the state apparatus, can create socialism without the old

bourgeois state first being destroyed by proletarian revolution in

which the working classnot various middle class surrogatesis the

principal historical actor.

As early as 1951, the sweeping political generalizations drawn by

Pablo from the peculiar circumstances of capitalisms overthrow in

Eastern Europe were worked into programmatic innovations whose

revisionist content went well beyond its linking of socialism to a

nuclear Armageddon (the theory of war-revolution). The

conception that there existed a road to socialism that did not depend

upon either the revolutionary initiative of a mass proletarian

movement or upon the construction of independent proletarian

parties led by Marxists became the ide fixe of Pabloism. Thus, the

central axis of its revisions was not simply its evaluation of Stalinism

and the possibilities for its self-reform. That was only one of the

many ugly faces of Pabloite revisionism.

The essential revision of Pabloism, and what has made it so useful

to imperialism, is its attack on the most fundamental premises of

scientific socialism. The scientifically-grounded conviction that the

liberation of the proletariat is the task of the proletariat itself and that

the task of socialism begins with the dictatorship of the proletariatas

Marx indicated as far back as 1851is directly challenged by

Pabloism, whose theory of socialism assigns the main role to the

petty bourgeoisie. And while Pabloism from time to time pays

formal homage to the working class, it never goes so far as to insist

that neither the overthrow of capitalism nor the construction of

socialism are possible without the existence of a very high level of

theoretical consciousness, produced through the many years of

struggle which are required to build a Marxist party, in a substantial

section of the proletariat.

The unrestrained opportunism which has always characterized the

tactics employed by the Pabloites flows inexorably from their

rejection of the proletarian foundation of socialism. The Marxist

understands that the education of the proletariat in a scientific

appreciation of its long-term historical tasks requires a principled

line. He therefore prefers temporary isolation to short-term gains that

are purchased at the expense of the political clarification of the

working class. But the Pabloite is not restrained by such

considerations. His tactics are directed toward the subordination of

the independence of the proletariat to whatever nonproletarian forces

temporarily dominate the mass movement. [Volume 14, No. 1,

March 1987, p. iii-iv]

The work that was carried out in the aftermath of the split with the

Workers Revolutionary Party was extraordinarily intense. I had the

privilege of working side by side with Keerthi on many of the documents

produced during that period. I recall the many hours of discussion out of

which the documents emerged. But I remember not only the political

discussions. Keerthis interests were wide-ranging.

Before he turned to politics, Keerthi, while still a student, had displayed

substantial promise as a poet. He possessed a broad knowledge of

literature, music and the arts. For all his intellectual rigor, Keerthi was

exceptionally kind and humane in his relationships with comrades and

friends. His socialist convictions flowed from a deep-rooted sympathy

with the conditions of the oppressed and concern for the fate of mankind.

Twenty years after his death, Comrade Keerthi remains a powerful

political and moral presence in our international movement. In the two

decades since his death, the political forces against which he fought

relentlesslythe bourgeois nationalists, the Stalinists, the Maoists, the

anti-Trotskyist renegades of the LSSP, the WRP and other revisionist

tendencieshave been discredited by events. The revolutionary offensive

of the working class will inevitably give rise to a renewed and passionate

interest in genuine Marxism. Enormous opportunities to expand the

political influence of the International Committee will soon present

themselves. But these opportunities must be grasped as a means of

achieving historical aims, rather than mere tactical advantages. It is

through the unrelenting struggle to uphold the perspective of world

socialist revolution that we honor the memory and continue the work of

Comrade Keerthi Balasuriya.

To contact the WSWS and the

Socialist Equality Party visit:

http://www.wsws.org

World Socialist Web Site

You might also like

- Hakibbutz Ha’artzi, Mapam, and the Demise of the Israeli Labor MovementFrom EverandHakibbutz Ha’artzi, Mapam, and the Demise of the Israeli Labor MovementNo ratings yet

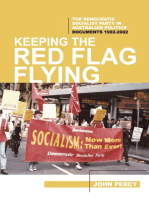

- Keeping the Red Flag Flying: The Democratic Socialist Party in Australian Politics: Documents, 1992-2002From EverandKeeping the Red Flag Flying: The Democratic Socialist Party in Australian Politics: Documents, 1992-2002No ratings yet

- The Spirit of '71Document35 pagesThe Spirit of '71Musaddek Abu SayekNo ratings yet

- B49 - The - Crisis - of - The - Chilean - Socialist - Party - (PSCH) - in - 1979 - Carmelo Furci PDFDocument32 pagesB49 - The - Crisis - of - The - Chilean - Socialist - Party - (PSCH) - in - 1979 - Carmelo Furci PDFFelipe López PérezNo ratings yet

- A Coalition For Violence Mass Slaughter in Indonesia 196566Document75 pagesA Coalition For Violence Mass Slaughter in Indonesia 196566Muhammad Adek UNPNo ratings yet

- Origins and Development of Traditional Leftist Movements in Sri LankaDocument7 pagesOrigins and Development of Traditional Leftist Movements in Sri LankakosalaNo ratings yet

- The Crisis of Chile's Socialist Party in 1979Document32 pagesThe Crisis of Chile's Socialist Party in 1979Camilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Stalin OutlineDocument4 pagesStalin OutlineIoanna MantaNo ratings yet

- Resurrection of Leftism A DilemnaDocument31 pagesResurrection of Leftism A DilemnaVidyut ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Indias Struggle For Independence Bipan ChandraDocument561 pagesIndias Struggle For Independence Bipan ChandraruthvikarNo ratings yet

- The Left and The 1972 Constitution by Kumar DavidDocument23 pagesThe Left and The 1972 Constitution by Kumar Daviddevaneshan.rNo ratings yet

- Marxist Approach To Study Nationalism in IndiaDocument16 pagesMarxist Approach To Study Nationalism in Indiavaibhavi sharma pathakNo ratings yet

- Carmelo Furci - PCCH PDFDocument16 pagesCarmelo Furci - PCCH PDFFelipe López PérezNo ratings yet

- Democracy's Uneven Growth Around the WorldDocument111 pagesDemocracy's Uneven Growth Around the WorldVijayakumarNo ratings yet

- From (Kanika K Simon (Simon - Kanikak@gmail - Com) ) - ID (555) - HISTORY21Document18 pagesFrom (Kanika K Simon (Simon - Kanikak@gmail - Com) ) - ID (555) - HISTORY21Raqesh MalviyaNo ratings yet

- Political Culture of BangladeshDocument32 pagesPolitical Culture of BangladeshBishawnath Roy100% (2)

- Srijan Basu Mallick Ug Semester - 6 POLS 022 POLS 682 Term PaperDocument9 pagesSrijan Basu Mallick Ug Semester - 6 POLS 022 POLS 682 Term PaperSrijan Basu MallickNo ratings yet

- Mother 1084Document11 pagesMother 1084Madhurai GangopadhyayNo ratings yet

- The Story of An Aborted Revolution: Communist Insurgency in Post-Independence West Bengal, 1948-50Document32 pagesThe Story of An Aborted Revolution: Communist Insurgency in Post-Independence West Bengal, 1948-50ragulaceNo ratings yet

- 1977 Pakistani Coup ExplainedDocument22 pages1977 Pakistani Coup Explainedجمی فینکسNo ratings yet

- Horace Davis - Lenin and NationalismDocument23 pagesHorace Davis - Lenin and NationalismLevan AsabashviliNo ratings yet

- Social Background of Mass Movements in India: Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University Lucknow, (A Central Universy)Document22 pagesSocial Background of Mass Movements in India: Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University Lucknow, (A Central Universy)shiv1610% (1)

- Historical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party - Britain 2010Document113 pagesHistorical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party - Britain 2010Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Labor Zionism, The State, and Beyond - An Interpretation of Changing Realities and Changing HistoriesDocument28 pagesLabor Zionism, The State, and Beyond - An Interpretation of Changing Realities and Changing HistoriesOrso RaggianteNo ratings yet

- The 1972 Republican Constitution in The Postcolonial Constitutional Evolution of Sri LankaDocument20 pagesThe 1972 Republican Constitution in The Postcolonial Constitutional Evolution of Sri LankaInshaff MSajeerNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Politics 1965-7: The September 30 Movement and The Fall of SukarnoDocument13 pagesIndonesian Politics 1965-7: The September 30 Movement and The Fall of SukarnoRaihan JustinNo ratings yet

- Communist International in Lenins TimeDocument42 pagesCommunist International in Lenins TimeRoberto MihaliNo ratings yet

- Casals - 2019 - Anticommunism in 20th-Century Chile From The "SocDocument30 pagesCasals - 2019 - Anticommunism in 20th-Century Chile From The "SocMarcelo Casals ArayaNo ratings yet

- Towards The Liberation of The Black Nation: Organize For The New Afrikan People's WarDocument26 pagesTowards The Liberation of The Black Nation: Organize For The New Afrikan People's WarMosi Ngozi (fka) james harris50% (2)

- Tilak and IncDocument15 pagesTilak and IncGanesh PrasaiNo ratings yet

- BriefHistoryOfMCCIandCPIMLPW Eng OCR PDFDocument71 pagesBriefHistoryOfMCCIandCPIMLPW Eng OCR PDFPremNo ratings yet

- Hindu NationalismDocument16 pagesHindu NationalismDurgesh kumarNo ratings yet

- 4 Social Background of Indian NationalismDocument8 pages4 Social Background of Indian NationalismShahbaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Tito The Formation of A Disloyal BolshevikDocument24 pagesTito The Formation of A Disloyal BolshevikMarijaNo ratings yet

- 4 Social Background of Indian NationalismDocument8 pages4 Social Background of Indian NationalismPranav Manhas86% (7)

- KMT-CCP Enmities JustificationsDocument15 pagesKMT-CCP Enmities JustificationsPartha911No ratings yet

- Unit 16 Socio-Cultural Issues: StructureDocument20 pagesUnit 16 Socio-Cultural Issues: StructureVivek JainNo ratings yet

- People Power Fund.20140316.173125Document2 pagesPeople Power Fund.20140316.173125alto28sundayNo ratings yet

- Political Culture of Bangladesh.Document31 pagesPolitical Culture of Bangladesh.Saeed Anwar100% (2)

- Marxist Approach To Study Indian NationalismDocument6 pagesMarxist Approach To Study Indian NationalismlularzaNo ratings yet

- A Socialist Project ReviewDocument52 pagesA Socialist Project ReviewsuperpanopticonNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument39 pagesUntitledHannah JosephNo ratings yet

- The Persecution of The LeftDocument7 pagesThe Persecution of The LeftKier CarlosNo ratings yet

- Foreword by Stephen Cohen Preface List of Abbreviations: VIII X XiiiDocument34 pagesForeword by Stephen Cohen Preface List of Abbreviations: VIII X XiiipannunfirmNo ratings yet

- 20 Ajitesh BandopadhyayDocument27 pages20 Ajitesh BandopadhyayDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- Cultural RevolutionDocument9 pagesCultural RevolutionJavier Rodolfo Paredes MejiaNo ratings yet

- Sayyid Qutb and Social Justice, 1945-1948Document19 pagesSayyid Qutb and Social Justice, 1945-1948Uvais AhamedNo ratings yet

- Agung - Ayu-Soeharto's New Order State: Imposed Illusions and Invented LegitimationsDocument56 pagesAgung - Ayu-Soeharto's New Order State: Imposed Illusions and Invented LegitimationsInstitut Sejarah Sosial Indonesia (ISSI)No ratings yet

- Totalitarian Movements and Political ReligionsDocument22 pagesTotalitarian Movements and Political Religions10131No ratings yet

- Listen to Bhagat Singh and March on the Path of RevolutionDocument1 pageListen to Bhagat Singh and March on the Path of RevolutionAkshay KaleNo ratings yet

- China, Class Collaboration, and the Killing Fields of Indonesia in 1965From EverandChina, Class Collaboration, and the Killing Fields of Indonesia in 1965Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Democracy and The Islamic State: Muslim Arguments For Political Change in IndonesiaDocument15 pagesDemocracy and The Islamic State: Muslim Arguments For Political Change in IndonesiaMusaabZakirNo ratings yet

- Communist Party of India (Marxist) : ProgrammeDocument41 pagesCommunist Party of India (Marxist) : ProgrammesuvromallickNo ratings yet

- Sri Lanka's path to independence and early political turmoilDocument5 pagesSri Lanka's path to independence and early political turmoilStefan LatuNo ratings yet

- A Case of Non-European Fascism: Chilean National Socialism in The 1930sDocument29 pagesA Case of Non-European Fascism: Chilean National Socialism in The 1930sBetul OzsarNo ratings yet

- Nam IDocument18 pagesNam Igugoloth shankarNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Independence in BangladeshDocument14 pagesThe Politics of Independence in BangladeshKarthik VadlamaniNo ratings yet

- 2 The Leninist Party: Education For SocialistsDocument44 pages2 The Leninist Party: Education For SocialistsDrew PoveyNo ratings yet

- Taisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and OurselvesDocument7 pagesTaisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and Ourselvesfromatob3404100% (1)

- The Rise of Islamic Religio-Political Movement in IndonesiaDocument30 pagesThe Rise of Islamic Religio-Political Movement in IndonesiaIrwan Malik MarpaungNo ratings yet

- Historical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party - Britain 2010Document113 pagesHistorical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party - Britain 2010Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Objections of Comrade Sanjaya Jayasekera To His Arbirary Suspension by SEP Leadership in June 2022Document20 pagesObjections of Comrade Sanjaya Jayasekera To His Arbirary Suspension by SEP Leadership in June 2022Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Anti-Terrorism Bill Special Determination by The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka - 20 Feb. 2024Document76 pagesAnti-Terrorism Bill Special Determination by The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka - 20 Feb. 2024Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Reply of Comrade Sanjaya Jayasekera To Socialist Equality Party GS Against His Expulsion in November 2022Document7 pagesReply of Comrade Sanjaya Jayasekera To Socialist Equality Party GS Against His Expulsion in November 2022Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Determination On The Online Safety Bill, The Bill and Amendments Proposed by AGDocument159 pagesSupreme Court Determination On The Online Safety Bill, The Bill and Amendments Proposed by AGSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- The Developing Countries and The World Economic Order by Anell & Nygren, 1980Document107 pagesThe Developing Countries and The World Economic Order by Anell & Nygren, 1980Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Proposed Broadcasting Regulatory Commission Bill - June 2023Document22 pagesProposed Broadcasting Regulatory Commission Bill - June 2023Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Online Safety Act - EnglishDocument60 pagesOnline Safety Act - EnglishKaveesha JayasundaraNo ratings yet

- Anti-Terrorism Bill (September 2023) of Sri Lanka: The Written Submissions To The Supreme Court On Behalf of Petitioner Poet Ahnaf JazeemDocument21 pagesAnti-Terrorism Bill (September 2023) of Sri Lanka: The Written Submissions To The Supreme Court On Behalf of Petitioner Poet Ahnaf JazeemSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Magistrate Court Further Reports and Proceedings Filed As P11 & P12 With Poet Ahnaf Jazeem's FR PetitionDocument222 pagesMagistrate Court Further Reports and Proceedings Filed As P11 & P12 With Poet Ahnaf Jazeem's FR PetitionSanjaya Wilson Jayasekera100% (1)

- 1948 by Colvin R de Silva - in SinhalaDocument14 pages1948 by Colvin R de Silva - in SinhalaSanjaya Wilson Jayasekera100% (1)

- Ceylon Under British Occupation 1795-1833, Vol. 01, Its Political and Administrative Development by Colvin R de Silva, 1931 Black&WhiteDocument188 pagesCeylon Under British Occupation 1795-1833, Vol. 01, Its Political and Administrative Development by Colvin R de Silva, 1931 Black&WhiteSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Ceylon Under British Occupation 1795-1833 Vol. 01 by Colvin R de SilvaDocument188 pagesCeylon Under British Occupation 1795-1833 Vol. 01 by Colvin R de SilvaSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Opinion by UN WGAD On The Arrest and Detention of Poet Ahnaf Jazeem 30 March - 8 April 2022 Opinion No. 22/2022 Concerning Ahnaf Jazeem (Sri Lanka)Document17 pagesOpinion by UN WGAD On The Arrest and Detention of Poet Ahnaf Jazeem 30 March - 8 April 2022 Opinion No. 22/2022 Concerning Ahnaf Jazeem (Sri Lanka)Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Neoliberal Constitutionalism and The Austerity State: The Resurgence of Authoritarianism in The Service of MarketDocument120 pagesNeoliberal Constitutionalism and The Austerity State: The Resurgence of Authoritarianism in The Service of MarketSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Understanding Marx's Capital: Globalization of Production and The Tasks of The International Working Class by Nick Beams - SLL-1993Document130 pagesA Guide To Understanding Marx's Capital: Globalization of Production and The Tasks of The International Working Class by Nick Beams - SLL-1993Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Poet and Teacher, Ahnaf Jazeem's Counter Affidavit in Response To The Limited Affidavit of Director TID, The 3rd RespondentDocument30 pagesPoet and Teacher, Ahnaf Jazeem's Counter Affidavit in Response To The Limited Affidavit of Director TID, The 3rd RespondentSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Petition Challenging The Twentieth Amendment To The Constitution Bill Published in Part II of Gazette of August 28, 2020Document17 pagesPetition Challenging The Twentieth Amendment To The Constitution Bill Published in Part II of Gazette of August 28, 2020Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Navarasam by Ahnaf Jazeem and Translations As Filed in The Supreme Court of Sri LankaDocument134 pagesNavarasam by Ahnaf Jazeem and Translations As Filed in The Supreme Court of Sri LankaSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Shakthika Sathkumara - Opinion of The Working Group On Arbitrary Detention of UN Human Rights CouncilDocument16 pagesShakthika Sathkumara - Opinion of The Working Group On Arbitrary Detention of UN Human Rights CouncilSanjaya Wilson Jayasekera100% (1)

- Code of Criminal ProcedureDocument98 pagesCode of Criminal ProcedureBhawani PratapNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Rights Petition Filed For Poet Ahnaf JazeemDocument28 pagesFundamental Rights Petition Filed For Poet Ahnaf JazeemSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Evidence Ordinance Consolidated Upto 2005Document111 pagesEvidence Ordinance Consolidated Upto 2005Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Conciliation Under The Industrial Disputes Act of Sri LankaDocument26 pagesConciliation Under The Industrial Disputes Act of Sri LankaSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Twentieth Amendment Judgement of The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, Decided in October 2020Document61 pagesTwentieth Amendment Judgement of The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, Decided in October 2020Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Act No.17 of 1981 Consolidated Sihala ActDocument24 pagesOmbudsman Act No.17 of 1981 Consolidated Sihala ActSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Industrial Relations, Trade Unions and Social DialogueDocument60 pagesIndustrial Relations, Trade Unions and Social DialogueSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Induatrial Disputes Act No.43 of 1950 As Amalgamated Up To Act No.39 of 2011Document44 pagesInduatrial Disputes Act No.43 of 1950 As Amalgamated Up To Act No.39 of 2011Sanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Customs Ordinance of Sri Lanka Consolidated and AnnotatedDocument140 pagesCustoms Ordinance of Sri Lanka Consolidated and AnnotatedSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Neoliberal Constitutionalism, The Second Republican Constitution and The Rise of AuthoritarianismDocument15 pagesNeoliberal Constitutionalism, The Second Republican Constitution and The Rise of AuthoritarianismSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Is Fascism Capitalism in DecayDocument65 pagesIs Fascism Capitalism in DecaySmith John100% (1)

- Arthur Moeller Van Den Bruck: The Man and His Thought - Lucian TudorDocument11 pagesArthur Moeller Van Den Bruck: The Man and His Thought - Lucian TudorChrisThorpeNo ratings yet

- Exam 2 Study GuideDocument19 pagesExam 2 Study Guideedomin00No ratings yet

- Murray Bookchin Post-Scarcity Anarchism 1996Document39 pagesMurray Bookchin Post-Scarcity Anarchism 1996Josué Ochoa ParedesNo ratings yet

- TheoDocument3 pagesTheoAshley LapusNo ratings yet

- John Roemer - A Future For Socialism-Harvard University Press (1994)Document180 pagesJohn Roemer - A Future For Socialism-Harvard University Press (1994)JoaquinNo ratings yet

- (Chapter6) Life in The Age of MachinesDocument39 pages(Chapter6) Life in The Age of MachinesJoshua ChanNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Caribbean DevelopmentDocument16 pagesTheorizing Caribbean DevelopmentzhaleneNo ratings yet

- SOCIALISM (5 Basic Questions Forerunners)Document25 pagesSOCIALISM (5 Basic Questions Forerunners)Kuang Yong NgNo ratings yet

- What is Maoism? Understanding revolutionary ideologiesDocument16 pagesWhat is Maoism? Understanding revolutionary ideologieshrundiNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory Text and Readings Paperback Second Edition by Scott A Appelrouth Laura D Desfor EdlesDocument8 pagesTest Bank For Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory Text and Readings Paperback Second Edition by Scott A Appelrouth Laura D Desfor EdlesPedro Chun100% (29)

- Analyzing Major Social Science Theories and IdeasDocument40 pagesAnalyzing Major Social Science Theories and IdeasJay Mark MartinezNo ratings yet

- A Journey Around Constitutions PDFDocument28 pagesA Journey Around Constitutions PDFBoss CKNo ratings yet

- Brahmastra 3Document18 pagesBrahmastra 3ramesh babu DevaraNo ratings yet

- The Modern World-System As A Capitalist World-Economy Production, Surplus Value, and PolarizationDocument11 pagesThe Modern World-System As A Capitalist World-Economy Production, Surplus Value, and PolarizationLee ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Legal PhilosophyDocument22 pagesLegal Philosophygentlejosh_316100% (2)

- Review of "Europe and the People Without HistoryDocument14 pagesReview of "Europe and the People Without HistoryLeonardo MarquesNo ratings yet

- 162 Kagarlitsky The Revolt of The Middle Class PDFDocument209 pages162 Kagarlitsky The Revolt of The Middle Class PDFhoare612No ratings yet

- Print WSWS Summary PlusDocument35 pagesPrint WSWS Summary Plusxan30tosNo ratings yet

- False Nationalism False InternationalismDocument211 pagesFalse Nationalism False InternationalismMofabioNo ratings yet

- Meerut Conspiracy Case, 1929-32 PDFDocument181 pagesMeerut Conspiracy Case, 1929-32 PDFHoyoung ChungNo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary CriticismDocument42 pagesMarxist Literary CriticismAlec Palcon JovenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 2Document18 pagesChapter 1 2Ryan MosendeNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Reinforcing Compensation and Deployment Policies For Government Nurses in The Philippines - UP SOLAIR, Carla GobDocument22 pagesAnalysis On Reinforcing Compensation and Deployment Policies For Government Nurses in The Philippines - UP SOLAIR, Carla GobCarla GobNo ratings yet

- MUSEVENI: Refocusing On The NRM Kyankwanzi 27 July 2016Document23 pagesMUSEVENI: Refocusing On The NRM Kyankwanzi 27 July 2016The Independent MagazineNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies) M. R. Myant - Socialism and Democracy in Czechoslovakia - 1945-1948-Cambridge University Press (1981)Document312 pages(Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies) M. R. Myant - Socialism and Democracy in Czechoslovakia - 1945-1948-Cambridge University Press (1981)danpp100No ratings yet

- IMPERIALISM AND REVOLUTIONARY STRUGGLE AGAINST IMPERIALISM IN THE ARAB-ISLAMIC WORLD AND IN THE METROPOLIS - Che FareDocument75 pagesIMPERIALISM AND REVOLUTIONARY STRUGGLE AGAINST IMPERIALISM IN THE ARAB-ISLAMIC WORLD AND IN THE METROPOLIS - Che Farekritisk kulturNo ratings yet

- Social Sciences: Understanding its Nature and DisciplinesDocument42 pagesSocial Sciences: Understanding its Nature and DisciplinesPaw Verdillo100% (1)

- The German Ideology - Feuerbach's Explanation of ContradictionsDocument5 pagesThe German Ideology - Feuerbach's Explanation of ContradictionsshirineNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx Political SociologyDocument9 pagesKarl Marx Political SociologyTariq Rind100% (3)