Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Neuro

Uploaded by

Aro0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views9 pagesm,,m

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentm,,m

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views9 pagesJurnal Neuro

Uploaded by

Arom,,m

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

RESEARCH ARTI CLE Open Access

Weight loss, dysphagia and supplement intake in

patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS):

impact on quality of life and therapeutic options

Sonja Krner

1*

, Melanie Hendricks

1

, Katja Kollewe

1

, Antonia Zapf

3

, Reinhard Dengler

1,2

, Vincenzo Silani

4,5

and Susanne Petri

1,2

Abstract

Background: Weight loss is a frequent feature in the motor neuron disease Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In

this study we investigated possible causes of weight loss in ALS, its impact on mood/quality of life (QOL) and the

benefit of high calorie nutritional/other dietary supplements and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG).

Methods: 121 ALS patients were interviewed and answered standardized questionnaires (Beck depression

inventory - II, SF36 Health Survey questionnaire, revised ALS functional rating scale). Two years after the initial

survey we performed a follow-up interview.

Results: In our ALS-cohort, 56.3% of the patients suffered from weight loss. Weight loss had a negative impact on

QOL and was associated with a shorter survival. Patients who took high calorie nutritional supplements respectively

had a PEG stated a great benefit regarding weight stabilization and/or QOL.

38.2% of our patients had significant weight loss without suffering from dysphagia. To clarify the reasons for weight

loss in these patients, we compared them with patients without weight loss. The two groups did not differ

regarding severity of disease, depression, frontotemporal dementia or fasciculations, but patients with weight loss

declared more often increased respiratory work.

Conclusions: Weight loss is a serious issue in ALS and cannot always be attributed to dysphagia. Symptomatic

treatment of weight loss (high calorie nutritional supplements and/ or PEG) should be offered more frequently.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Nutrition, Dietary supplements, Weight loss, Dysphagia, High calorie

supplements

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the most common

adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder of the motor sys-

tem. It is characterized by loss of upper and lower motor

neurons in the primary motor cortex, brainstem and

spinal cord. The resulting paralyses are rapidly progressive

and lead to death due to respiratory failure within 2

5 years [1]. Weight loss is a frequent phenomenon in ALS.

It occurs not only in association with dysphagia but also

due to not yet fully understood disease-specific reasons.

Hypotheses to explain weight loss in ALS include higher

waste of energy because of muscle fasciculations, increas-

ing respiratory efforts, hypermetabolism and decreased

food intake due to depression [2-4]. In any case it is well

known that weight loss and a lower body-mass-index

(BMI) are negative prognostic factors for survival in ALS

[5-8]. High-energy diet prolonged survival in transgenic

ALS mice [9]. However, administration of high calorie nu-

tritional supplements or percutaneous endoscopic gastros-

tomy (PEG) in case of weight loss is not considered early

and frequently enough.

In contrast, self-medication with other dietary supple-

ments, also called nutriceuticals or functional food

has become increasingly popular among ALS patients

and according to the literature is used by up to 80% of

them [7,10]. Dietary supplements are supposed to affect

* Correspondence: Koerner.Sonja@mh-hannover.de

1

Department of Neurology, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1,

Hannover 30625, Germany

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

2013 Krner et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

diverse mechanisms leading to motor neuron death or

alleviate symptoms of ALS, often based on theoretical

benefits or anecdotal reports [7]. Frequently they are

self-prescribed and patients take several dietary supple-

ments simultaneously.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the

extent of weight loss in ALS and to analyse the impact

of weight loss on mood, quality of life (QOL) and sur-

vival of ALS patients. Additionally potential underlying

causes of weight loss beyond dysphagia should be evalu-

ated. Further we were interested in the frequency and

benefit of PEG insertion, high-calorie supplement (e.g.

calorically dense shakes/drinks) and other dietary sup-

plement (e.g. vitamins, homeopathic medication) intake

in ALS-patients.

Methods

121 ALS patients from the ALS outpatient clinic at

Hannover Medical School participated in the survey. The

study has been approved by the ethical committee of the

Hannover Medical School and all subjects gave informed

consent to the participation. All patients had met the re-

vised El Escorial criteria for probable or definite ALS. Only

in one patient, subtle clinical signs of frontotemporal de-

mentia (FTD) were present. FTD was underrepresented in

our population because these patients are less motivated

and less suitable to participate in this type of study. Pa-

tients filled in three standardized questionnaires (Beck de-

pression inventory - II (BDI), SF-36 Health Survey

questionnaire (SF-36) and revised ALS functional rating

scale (ALS-FRS-R)) and were further interviewed about

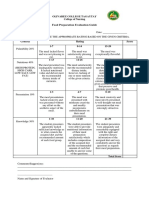

Table 1 Applied tests/questionnaires and their range and meaning

Test/questionnaires Range

Self designed questionnaire:

Collected information about presence of weight loss, dysphagia, supplement intake,

fasciculations, respiratory effort, high calorie supplement intake, PEG

patients had to choose yes or no

Included the questions: patients had to choose one of the answers

- How did the PEG insertion/high calorie supplement intake affect your weight? - Further weight loss, weight stabilization,

weight gain

- How did the PEG insertion influence your quality of life? - strong improvement, moderate

improvement, decline, no influence

Collected data about age, duration of disease, region of onset, sort of supplement. free text

ALSFRS_R total 0 (maximum disability) to 48 (normal)

ALSFRS_R bulbar 0 (maximum bulbar involvement) to 12 (no

bulbar involvement)

BDI 0 (no depression) to 63 (severe depression)

SF36 0 (poorest health) to 100 (best health)

Table 2 Group composition and characteristics of patients with and without dietary supplement intake/weight loss

Number of

patients

Gender Mean age

(years)

Mean disease

duration (months)

Mean

ALSFRS_R

total

Mean

ALSFRS_R

bulbar

Percentage of bulbar

onset patients (%)

total 121 81 male 40

female

59.74 41.4 29.29 8.66 11.6

with supplement

intake

67* 49 male 18

female

56.63 36.7 31.11 9.4 6.0

without

supplement intake

50* 30 male 20

female

63.56 45.8 26.92 7.83 14.0

weight loss 68 47 male 21

female

61.0 30 27.5 7.67 14.7

weight loss with

dysphagia

42 29 male 13

female

60.67 29 22.9 5.56 21.4

weight loss

without dysphagia

26 18 male 8

female

61.54 31.8 30.52 11.12 3.8

no weight loss 53 34 male 19

female

58,11 54.5** 33.82 9.94 7.5

* Four patients did not make any statement regarding supplement intake.

** Disease duration significant different from the groups weight loss and weight loss with dysphagia.

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 2 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

weight loss, dysphagia, food habits and their intake of diet-

ary supplements. It was documented if patients suffered

fasciculations or respiratory distress (yes or no).

Two years after the initial survey, 61.2% of the patients

or their relatives were available for a short follow-up

telephone interview to find out whether the patient was

still alive and whether the patient still used dietary

supplements.

The ALSFRS_R is a well-established and widely used

score for the functional status of patients with ALS [11].

It is based on 12 items, each rated on a 04 point scale.

The rate of functional disability ranges from 0 (max-

imum disability) to 48 (normal) points. Three items of

the ALSFRS_R assess bulbar involvement (speech, saliva-

tion, swallowing), which therefore can be rated from 0

(maximum bulbar involvement) to 12 (no bulbar

involvement).

The BDI is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report

inventory and a commonly used instrument for quantify-

ing levels of depression. Each of the 21 items is scored

on a scale value of 0 (symptom not present) to 3 (symp-

tom very intense) leading to an overall-range of 63. The

cutoffs used are 08: no depression, 913: minimal de-

pression, 1419: mild depression, 2028: moderate de-

pression, 2963 severe depression [12].

The SF36 questionnaire is a multi-purpose, short-form

health survey with 36 questions. It is a self-administered

QOL scoring system that includes eight independent

scales: 1. physical functioning (limitations in physical ac-

tivities), 2. Physical role (limitations in usual role activities

Figure 1 Mean scores of ALSFRS_R and SF36 questionnaire of patients without and with weight loss and impact of high calorie

supplements/PEG. Mean scores of ALSFRS_R (A) and SF36 questionnaire (B) of patients without and with weight loss. The latter group showed

significantly lower scores at the ALSFRS_R and the SF36 subscales physical functioning and vitality. 58.3% of patients consuming high calorie

supplements and 76.9% of patients who had undergone PEG reported subsequent weight stabilization or even weight gain (C and D). * p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01.

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 3 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

because of physical health problems), 3. Bodily pain, 4.

General health perception, 5. Vitality (energy and fa-

tigue), 6. social functioning (limitations in social activities

because of physical or emotional problems), 7. Emotional

role (limitations in usual role activities because of emo-

tional problems), 8. Mental health (psychological distress

and well-being) [13]. The SF-36 questionnaire is widely

used and appropriate in ALS patients [14].

The tests and questionnaires used in this study are

briefly summarized in Table 1.

Patients were divided in the following groups: weight

loss (defined as >3 kg since disease onset), again

subdivided in weight loss without/with dysphagia and

no weight loss and, for the second aspect of the study,

with supplement intake and without supplement in-

take (supplement defined here as dietary supplements

(e.g. vitamins)). The groups did not differ regarding gender

or site of onset. Disease severity (ALSFRS_R), extent of de-

pression (BDI) and quality of life (SF36) were compared

between these patient groups (group composition see

Table 2) using t-tests for independent samples. To identify

correlations between weight loss or supplement intake

and QOL independent from disease severity (ALSFRS-R)

we performed multiple regression analysis (dependent

variable: SF-36 subscale, predictor variables: ALSFRS-R

and weight loss or supplement intake). Statistical analyses

were performed using SPSS V. 19 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) soft-

ware, a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

56.2% (n = 68) of the patients in our cohort reported

about weight loss. Weight loss was associated with a sig-

nificantly worse ALSFRS_R score and also with higher

depression (BDI, not significant) and significantly lower

QOL scores (SF36) regarding the subscales physical

functioning and vitality (Figure 1A and B). Multiple

regression analysis identified the ALSFRS_R score as

confounding factor, showing that the differences in BDI

and physical functioning were probably caused by the

discrepancy in the ALSFRS_R. But the difference in the

SF36 subscale vitality between patients with and with-

out weight loss remained highly significant (Table 3A),

which means that patients with weight loss feel more

often exhausted, tired and spiritless, regardless of the

disease stage. Multiple regression analysis showed that

this influence of weight loss on vitality was independent

of respiratory distress which had a significant effect on

vitality as well (Table 3B).

33.8% (n = 23) of patients with weight loss consumed

high calorie supplements and 60.8% (n = 14) of these

reported subsequent weight stabilization or even weight

gain (Figure 1C). 25.5% (n = 13) of patients with dysphagia

had undergone PEG; 76.9% (n = 10) of these patients de-

clared weight stabilization or weight gain (Figure 1D) and

84.6% (n = 11) stated an improvement of QOL after PEG

insertion. Remarkably, no patient indicated deterioration of

QOL after PEG insertion (although this is often suspected

by patients and relatives prior to the procedure).

38.2% (n = 26) of patients with weight loss did not suf-

fer from dysphagia (according to self-reported statement

and ALSFRS_R). This patient group did not differ from

patients without weight loss regarding ALSFRS_R (total

and bulbar) and depression (BDI) nor did they report

changes in their eating habits. Patients with dysphagia

on the other hand showed significantly lower ALSFRS_R

scores, mainly due to the bulbar subscore (Figure 2A).

The prevalence of fasciculations in patients with weight

loss without dysphagia was equal to patients without

weight loss. They did, however, more often declare in-

creased respiratory efforts compared to patients without

weight loss (Figure 2B).

The telephone survey after two years showed that

weight loss was a strong negative prognostic factor:

Kaplan- Meier survival curves of patients with and with-

out weight loss showed significantly shorter survival of pa-

tients with weight loss (log rank p = 0.001) (Figure 2C).

54.5% (n = 67) of the patients stated regular intake of

other (not high-calorie) dietary supplements (e.g. vitamins).

44.8% (n = 30) of them consumed more than one supple-

ment, some up to five simultaneously or preparations

Table 3 Multiple regression analysis of the SF36 subscale

vitality and weight loss (A and B) respectively the SF36

subscale social functioning and supplement intake (C)

A

Vitality Regression coefficient p-value

(SF-36 scale)

ALSFRS_R 0,416 0,013

Weight loss 9,281 0,011

B

Vitality Regression coefficient p-value

(SF-36 scale)

Respiratory distress 10.093 0,005

Weight loss 9,457 0,008

C

Social Functioning Regression coefficient p-value

(SF-36 scale)

ALSFRS_R 0,628 0,010

Supplement intake 14,342 0,008

Multiple regression analysis of the SF36 subscale vitality and weight loss (A

and B) respectively the SF36 subscale social functioning and supplement

intake (C) taking into account the influence of the ALSFRS_R score/respiratory

distress. The calculations showed an independent significant influence of both

weight loss/supplement intake and ALSFRS_R score/respiratory distress on

vitality respectively social functioning: Patients with weight loss and lower

ALSFRS_R showed worse results regarding vitality (A and B) and patients

with supplement intake and higher ALSFRS_R showed better results regarding

social functioning (C).

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 4 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

containing up to seven ingredients. Overall 23 different

supplements were mentioned (Table 4). Analysis of the

ALSFRS_R showed an inverse correlation between disease

severity and supplement intake (i.e. patients taking diet-

ary supplements were significantly less impaired than

those who did not) (Figure 3A). There also was a signifi-

cant difference in the BDI scores as well as the SF-36

subscales physical functioning, vitality and social

functioning between the two groups: patients with sup-

plement intake were significantly better regarding mood

and QOL (Figure 3B and C). However, multiple regres-

sion analysis again showed that these differences are

mainly attributable to the discrepancies in disease severity

as assessed by the ALSFRS_R (=confounding factor). Only

the difference in social functioning between patients

with and without supplement intake remained highly sig-

nificant, showing an independent influence of both sup-

plement intake and ALSFRS_R (Table 3C). Hence patients

using dietary supplements are feeling less affected in their

social functioning which means contact or visit family

members, friends and neighbours. However it could also

be the other way around, meaning that patients with a

more active social life are more likely to start taking diet-

ary supplements. At the follow-up telephone interview

two years after the first survey, 42.9% of the patients who

had initially reported use of dietary supplements now de-

clared that they had stopped any supplement intake.

Discussion

According to the literature, weight loss is associated with

shorter survival. In our ALS population it was accordingly

connected with a significantly worse mean ALSFRS_R

score and a significantly higher death rate after two years.

Weight loss had a significant impact on QOL regarding

the SF36 subitem vitality, meaning that it made patients

feel more exhausted, tired and spiritless, regardless of the

Figure 2 Comparison of patients with weight loss with/without

dysphagia and patients without weight loss. Patients with

weight loss and dysphagia differed significantly from patients

without weight loss in BDI and ALSFRS_R (total and bulbar). Patients

with weight loss without dysphagia, on the other hand, did not

have higher BDI/ lower ALSFRS_R scores than patients without

weight loss (A). Weight loss in patients without dysphagia therefore

does not seem to be directly related to a more advanced disease

stage or increased depression. Patients with weight loss and

dysphagia significantly more often declared increased respiratory

work than patients without weight loss. Patients with weight loss

without dysphagia showed a tendency towards increased respiratory

work compared to patients without weight loss (p = 0.12). There

were no differences regarding frequency of fasciculations between

the groups (B). Follow-up by telephone two years after the initial

survey highlighted the prognostic value of weight loss: Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis for ALS patients with and without weight loss

revealed significantly shorter survival of ALS patients with weight

loss (log rank p = 0.001) (C).

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 5 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

respective disease stage. Nevertheless, high calorie nutri-

tional supplements were only consumed by one third of

patients with weight loss, mainly due to the fact that the

costs are often not covered by the respective health insur-

ances. According to our survey, substantial benefit can be

obtained from high calorie supplements and they should

therefore be given more frequently. Only one quarter of

patients with dysphagia had undergone PEG placement.

Most of these patients reported weight stabilization and

improvement of QOL. The decision about PEG insertion

is mostly based on nutritional status and presence of

dysphagia [16,17]. From clinical practise it is known,

that patients are often cautious accepting a PEG, even

when food intake becomes time consuming and laborious.

Neurologists also tend to postpone the discussion of PEG

[18]. As a result, PEG placement is often initiated too

late and therefore associated with higher complication

rates as it is known that FVC >50% at the time of PEG

insertion is an important prognostic factor [16,18-20].

Our data confirm that PEG placement can stabilize

body weight [10,21,22] and suggest additionally an im-

pact on the QOL. The impact of PEG on QOL has been

studied very little so far. Beside anecdotal impressions,

only one study collected quantitative data: here, the ma-

jority of the patients mentioned stabilized nutritional and

hydrational status as most positive effect of PEG. Fewer

patients listed less fatigue or less time spent on meals and

improved psychological wellbeing as positive effects of

PEG [21,23]. Interestingly, in our cohort, even patients

who had undergone further weight loss after PEG in-

sertion, unanimously stated improvement of QOL. This

suggests that other factors such as reduction of time con-

suming and tiring food and fluid intake with frequent

choking are equally important for patients.

A further important result of our study is that weight loss

without dysphagia is frequent in ALS. We aimed to define

what distinguishes these patients from patients without

weight loss. As the groups did not differ regarding site of

onset and gender, these factors could not be relevant. While

thorough neuropsychological testing had not been routinely

performed, clinical signs of dementia were only detectable

in one of the patients without weight loss, so that weight

loss in the patients without dysphagia in our cohort could

not be attributed to major cognitive or behavioural abnor-

malities. Patients with weight loss without dysphagia did

not show differences in disease severity, grade of depres-

sion or presence of muscle fasciculations, but they did re-

port higher respiratory efforts. It remains unclear how far

this contributes to the weight loss. Two studies in ALS pa-

tients did not detect a relation between forced vital cap-

acity (FVC) and energy expenditure (REE) [2,24] while

two others suggest that increased respiratory efforts cause

elevated REE [25,26]. Based on the existing literature, this

increased energy consumption in ALS can probably not

only be explained by respiratory insufficiency but rather

by general hypermetabolism which occurs in about 50% of

ALS patients and whose origin has not yet been fully elu-

cidated [4,24].

The proportion of patients taking other, not high cal-

orie dietary supplements such as vitamins was lower in

our cohort (with 54.5%) than in the literature, were the

percentage of supplement intake among ALS-patients is

estimated as approximately 80% [7,10].

The observed differences in disease severity, depres-

sion and QOL are most probably not a direct effect of

these diverse dietary supplements. While one must take

into account a certain placebo-effect, the most likely ex-

planation is that patients self-medicating with dietary

Table 4 Nutritional supplements and functional foods

taken in our population [15]

Nutritional

supplement

Mechanism of action

(hypothesis)

Percentage (%) in

our population

Magnesium Against cramps 63,6

Vitamin E Antioxidant 40,3

Vitamin B (6 + 12) Other agent 13,6

Vitamin C Antioxidant 10,6

Vitamins, not

specified

Antioxidant 7,6

Homeopathic

medication

4,5

Folate Other 4,5

Calcium Bone regeneration 3,0

Carnitin Antioxidant/

Mitochondrial stabilizer

3,0

CoQ10 Antioxidant/

Mitochondrial stabilizer

3,0

Schussler salts 3,0

L-Arginin Muscle regeneration 3,0

Zinc Other 3,0

Vitamin A Antioxidant 1,5

Lipoic acid (Omega3) Antioxidant/Anti-

glutamate

1,5

Grape seed extract Antioxidant/Anti-

glutamate

1,5

Vitamin D Other 1,5

Lycopin (tomato) Antioxidant, Radical

scavenger

1,5

Selen Radical scavenger 1,5

Enzymes (Papain,

(Chymo)Trypsin)

Antithrombotic,

eupeptic

1,5

Protein preparation Muscle regeneration 1,5

Willow capsules Against pain 1,5

Chlorella Against heavy metals 1,5

Himalaya salt 1,5

Not specified 12,1

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 6 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

Figure 3 Mean scores of ALSFRS-R, BDI and SF36 of patients with and without intake of dietary supplements. Mean scores of ALSFRS-R

(A), BDI (B) and SF36 (C) of patients with and without intake of other (not high calorie) dietary supplements. Supplement intake was associated

with significantly higher scores at the ALSFRS_R and the SF36 subscales physical functioning, vitality and social functioning and significantly

lower scores in BDI. * p < 0.05.

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 7 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

supplements presumably represent a more hopeful and

optimistic subgroup. This assumption is supported by

the fact that they had higher SF36 social functioning

scores, i.e. felt less affected in their interactions with

family members, friends and neighbours. A more active

social life may also have provided increased stimulations

to try alternative treatment approaches. Discontinuation

of dietary supplements over time (as revealed by our

two-year follow-up interview) presumably is the result of

loss of hope generally associated with further disease

progression.

Although there is a lack of evidence for any rele-

vant benefit of dietary supplements, as long as there

is no clear contraindication and as long as efficient

neuroprotective drugs beyond riluzole have not been

discovered, self-medication with dietary supplements

may represent hope and confidence for some pa-

tients and thereby have a positive impact on the dis-

ease course and quality of life.

Conclusion

The significance of the present study is limited because

it is retrospective and based on subjective data from the

patients themselves. Nevertheless it provides valuable in-

formation that can be used as a starting point for further

prospective investigations.

Even though malnutrition is a significant and inde-

pendent prognostic factor in survival, it is often inad-

equately addressed in clinical practice. According to our

results the effect of high calorie nutritional supplements

and PEG is often higher than expected. Patients, caregivers

and physicians should therefore be encouraged to consider

these measures. However, their benefit still requires fur-

ther confirmation by prospective studies.

To evaluate the reasons of weight loss beside dysphagia,

further prospective analysis of patients without weight loss

in comparison to patients suffering from weight loss not

attributable to dysphagia, comparing clinical parameters

such as fasciculations, spasticity and cognitive or behav-

ioural abnormalities together with REE and FVC will cer-

tainly provide more thorough understanding of this

phenomenon. In any case the existence of these different

phenotypes highlights once more the heterogeneity in the

clinical presentation of ALS.

Regarding dietary supplements, further studies are needed

to evaluate the safety and efficacy of numerous dietary sup-

plements and to enable appropriate recommendations.

Abbreviations

ALS: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS_R ALS: Functional rating

scale revised version; BDI: Beck depression inventory; BMI: Body mass

index; FVC: Flow vital capacity; PEG: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy;

QOL: Quality of life; REE: Resting energy expenditure; SF36: Short Form 36

health survey.

Competing interest

The study was not externally funded. The authors declare no conflict of

interest in regarding this manuscript.

Authors contributions

SK and SP designed the study and drafted the article. MH and KK

contributed to acquisition of data and revised the article critically for

important intellectual content, SK and AZ analyzed and interpreted the data,

AZ also revised the article critically for important intellectual content. RD and

VS contributed to conception of the study and revised the article critically

for important intellectual content. All authors give final approval of the

version to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andreas Niesel and Dagmar Conradt for technical

assistance.

Author details

1

Department of Neurology, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1,

Hannover 30625, Germany.

2

Center for Systems Neuroscience (ZSN),

Hannover, Germany.

3

Department of Medical Statistics, University Gttingen,

Gttingen, Germany.

4

Department of Neurology and Laboratory of

Neuroscience, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan 20149, Italy.

5

Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Dino Ferrari Center,

Universit degli Studi di Milano, Milan 20149, Italy.

Received: 17 January 2013 Accepted: 11 July 2013

Published: 12 July 2013

Reference

1. Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis

2009, 4:3.

2. Bouteloup C, Desport JC, Clavelou P, Guy N, Derumeaux-Burel H, Ferrier A,

Couratier P: Hypermetabolism in ALS patients: an early and persistent

phenomenon. J Neurol 2009, 256:12361242.

3. Vaisman N, Lusaus M, Nefussy B, Niv E, Comaneshter D, Hallack R, Drory VE:

Do patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have increased

energy needs? J Neurol Sci 2009, 279:2629.

4. Desport JC, Torny F, Lacoste M, Preux PM, Couratier P: Hypermetabolism in

ALS: correlations with clinical and paraclinical parameters.

Neurodegener Dis 2005, 2:202207.

5. Dupuis L, Pradat PF, Ludolph AC, Loeffler JP: Energy metabolism in

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2011, 10:7582.

6. Desport JC, Preux PM, Truong TC, Vallat JM, Sautereau D, Couratier P:

Nutritional status is a prognostic factor for survival in ALS patients.

Neurology 1999, 53:10591063.

7. Rosenfeld J, Ellis A: Nutrition and dietary supplements in motor neuron

disease. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2008, 19:573589.

8. Paganoni S, Deng J, Jaffa M, Cudkowicz ME, Wills AM: Body mass index,

not dyslipidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2011, 44:2024.

9. Dupuis L, Oudart H, Rene F, de Aguilar JL G, Loeffler JP: Evidence for

defective energy homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: benefit of

a high-energy diet in a transgenic mouse model. model. Proc Natl Acad

Sci U S A 2004, 101:1115911164.

10. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, England JD, Forshew D, Johnston W,

Kalra S, Katz JS, Mitsumoto H, Rosenfeld J, Shoesmith C, Strong MJ,

Woolley SC: Practice parameter update: The care of the patient with

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory

therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards

Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2009,

73:12181226.

11. Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, Nakanishi

A: The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates

assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III).

J Neurol Sci 1999, 169:1321.

12. Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W: Comparison of Beck Depression

Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 1996,

67:588597.

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 8 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

13. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey

(SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992,

30:473483.

14. Jenkinson C, Hobart J, Chandola T, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Swash M: Use of

the short form health survey (SF-36) in patients with amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis: tests of data quality, score reliability, response rate and scaling

assumptions. J Neurol 2002, 249:178183.

15. Cameron A, Rosenfeld J: Nutritional issues and supplements in

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2002, 5:631643.

16. Andersen PM, Abrahams S, Borasio GD, de Carvalho M, Chio A, Van Damme

P, Hardiman O, Kollewe K, Morrison KE, Petri S, Pradat PF, Silani V, Tomik B,

Wasner M, Weber M: EFNS guidelines on the clinical management of

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS)revised report of an EFNS task

force. Eur J Neurol 2012, 19:360375.

17. Heffernan C, Jenkinson C, Holmes T, Feder G, Kupfer R, Leigh PN, McGowan

S, Rio A, Sidhu P: Nutritional management in MND/ALS patients: an

evidence based review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord

2004, 5:7283.

18. Silani V, Kasarskis EJ, Yanagisawa N: Nutritional management in

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol 1998,

245(Suppl 2):S13S19.

19. Shaw AS, Ampong MA, Rio A, Al Chalabi A, Sellars ME, Ellis C, Shaw CE,

Leigh NP, Sidhu PS: Survival of patients with ALS following institution of

enteral feeding is related to pre-procedure oximetry: a retrospective

review of 98 patients in a single centre. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2006,

7:1621.

20. Kasarskis EJ, Scarlata D, Hill R, Fuller C, Stambler N, Cedarbaum JM: A

retrospective study of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in ALS

patients during the BDNF and CNTF trials. J Neurol Sci 1999, 169:118125.

21. Katzberg HD, Benatar M: Enteral tube feeding for amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011. Issue 1.

Art. No.: CD004030.

22. Mazzini L, Corra T, Zaccala M, Mora G, Del Piano M, Galante M:

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and enteral nutrition in

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 1995, 242:695698.

23. Mitsumoto H, Davidson M, Moore D, Gad N, Brandis M, Ringel S, Rosenfeld

J, Shefner JM, Strong MJ, Sufit R, Anderson FA: Percutaneous endoscopic

gastrostomy (PEG) in patients with ALS and bulbar dysfunction.

Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2003, 4:177185.

24. Desport JC, Preux PM, Magy L, Boirie Y, Vallat JM, Beaufrere B, Couratier P:

Factors correlated with hypermetabolism in patients with amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2001, 74:328334.

25. Kasarskis EJ, Berryman S, Vanderleest JG, Schneider AR, McClain CJ:

Nutritional status of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: relation

to the proximity of death. Am J Clin Nutr 1996, 63:130137.

26. Shimizu T, Hayashi H, Tanabe H: Energy metabolism of ALS patients under

mechanical ventilation and tube feeding. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 1991,

31:255259.

doi:10.1186/1471-2377-13-84

Cite this article as: Krner et al.: Weight loss, dysphagia and supplement

intake in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): impact on

quality of life and therapeutic options. BMC Neurology 2013 13:84.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color gure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Krner et al. BMC Neurology 2013, 13:84 Page 9 of 9

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/13/84

You might also like

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 18: PsychiatryFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 18: PsychiatryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Eating Disorders - Overview of Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument39 pagesEating Disorders - Overview of Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDylanNo ratings yet

- Fibromyalgia Syndrome Improved Using A Mostly Raw Vegetarian Diet: An Observational StudyDocument8 pagesFibromyalgia Syndrome Improved Using A Mostly Raw Vegetarian Diet: An Observational StudyThiago NunesNo ratings yet

- Mccann2015 Chori BarDocument15 pagesMccann2015 Chori BarMarko BrzakNo ratings yet

- Dietary Aspects in Fibromyalgia Patients: Results of A Survey On Food Awareness, Allergies, and Nutritional SupplementationDocument7 pagesDietary Aspects in Fibromyalgia Patients: Results of A Survey On Food Awareness, Allergies, and Nutritional SupplementationAura PalasNo ratings yet

- J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2023 - Aprahamian - Anorexia of Aging An International Assessment of HealthcareDocument14 pagesJ Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2023 - Aprahamian - Anorexia of Aging An International Assessment of HealthcareMauricio LorcaNo ratings yet

- 8omega-3 Supplementation Effects On Body Weight and DepressionDocument7 pages8omega-3 Supplementation Effects On Body Weight and DepressionMaikon MarquêsNo ratings yet

- Dietary Counselling and Food Fortification in Stable COPD: A Randomised TrialDocument7 pagesDietary Counselling and Food Fortification in Stable COPD: A Randomised TrialJames Cojab SacalNo ratings yet

- The Correlation Between Insulin Resistance and Left Ventricular Systolic Function in Obese WomenDocument4 pagesThe Correlation Between Insulin Resistance and Left Ventricular Systolic Function in Obese WomenAgus MahendraNo ratings yet

- Outcomes of Obese, Clozapine-Treated Inpatients With Schizophrenia Placed On A Six-Month Diet and Physical Activity ProgramDocument7 pagesOutcomes of Obese, Clozapine-Treated Inpatients With Schizophrenia Placed On A Six-Month Diet and Physical Activity ProgramnajibrendraNo ratings yet

- Correlates of Quality of Life in Older Adults With DiabetesDocument5 pagesCorrelates of Quality of Life in Older Adults With DiabetesGibran IlhamNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle Behaviors and Physician Advice For Change Among Overweight and Obese Adults With Prediabetes and Diabetes in The United States, 2006Document10 pagesLifestyle Behaviors and Physician Advice For Change Among Overweight and Obese Adults With Prediabetes and Diabetes in The United States, 2006Agil SulistyonoNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle Behaviors and Physician Advice For Change Among Overweight and Obese Adults With Prediabetes and Diabetes in The United States, 2006Document9 pagesLifestyle Behaviors and Physician Advice For Change Among Overweight and Obese Adults With Prediabetes and Diabetes in The United States, 2006Agil SulistyonoNo ratings yet

- Allama Iqbal Open University, IslamabadDocument22 pagesAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabadazeem dilawarNo ratings yet

- REDALYGDocument8 pagesREDALYGjoel cedeño SánchezNo ratings yet

- 2 Year Paleo TrialDocument8 pages2 Year Paleo TrialOfer KulkaNo ratings yet

- Eating Disorders CPGDocument62 pagesEating Disorders CPGLuis Pablo HsNo ratings yet

- Da QingDocument18 pagesDa QingAlina PopaNo ratings yet

- Medical Nutrition Therapy For Hemodialysis PatientsDocument24 pagesMedical Nutrition Therapy For Hemodialysis Patientsraquelt_65No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0261561423002844 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0261561423002844 MainRoland GarrozNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Nutritional Status of Patients WithDocument9 pagesEvaluation of Nutritional Status of Patients WithTupperware NeenaNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2005 Wilson 1074 81Document8 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2005 Wilson 1074 81Ilmi Dewi ANo ratings yet

- Weight Management Clinical TrialsDocument7 pagesWeight Management Clinical TrialschuariwapoohNo ratings yet

- Low Carb StudyDocument15 pagesLow Carb StudycphommalNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0026049511003404 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0026049511003404 MainFrankis De Jesus Vanegas RomeroNo ratings yet

- Hanai 2020Document12 pagesHanai 2020Thinh VinhNo ratings yet

- Adhrnc Articl Simpl UnderstandDocument7 pagesAdhrnc Articl Simpl UnderstandMary Ann OquendoNo ratings yet

- Cardioresp and Young Adults With DiabetesDocument8 pagesCardioresp and Young Adults With DiabetesNicole GreeneNo ratings yet

- Executive Functioning and Psychological Symptoms in Food Addiction: A Study Among Individuals With Severe ObesityDocument10 pagesExecutive Functioning and Psychological Symptoms in Food Addiction: A Study Among Individuals With Severe ObesityAnand Prakash KaurNo ratings yet

- Paper Impact of Overweight and Obesity On Health-Related Quality of Life - A Swedish Population StudyDocument8 pagesPaper Impact of Overweight and Obesity On Health-Related Quality of Life - A Swedish Population Studyuswatun khasanahNo ratings yet

- HOMA Medicion EJIM2003Document6 pagesHOMA Medicion EJIM2003Dr Dart05No ratings yet

- Calorie Restriction With or Without Exercise On Insulin Sensitivity Beta Cell Functions Ectopic LipidDocument8 pagesCalorie Restriction With or Without Exercise On Insulin Sensitivity Beta Cell Functions Ectopic Lipidadibahfauzi85No ratings yet

- Ketogenic Diet IF-Philippine Lipid Society Consensus-Statement-20191108v4Document21 pagesKetogenic Diet IF-Philippine Lipid Society Consensus-Statement-20191108v4donmd98No ratings yet

- Sunghwan Suh JournalDocument11 pagesSunghwan Suh JournalLISTIA NURBAETINo ratings yet

- tmp9C4E TMPDocument3 pagestmp9C4E TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Delisting of Infants and Children From The Heart Transplantation Waiting List After Carvedilol TreatmentDocument5 pagesDelisting of Infants and Children From The Heart Transplantation Waiting List After Carvedilol TreatmentwahyuraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CA FixDocument7 pagesJurnal CA FixRobby GumawanNo ratings yet

- Senam Bugar Lansia Berpengaruh Terhadap Daya Tahan Jantung Paru, Status Gizi, Dan Tekanan DarahDocument9 pagesSenam Bugar Lansia Berpengaruh Terhadap Daya Tahan Jantung Paru, Status Gizi, Dan Tekanan DarahBilal MashelNo ratings yet

- Obesity in Children and Adolescents:: Identifying Eating DisordersDocument5 pagesObesity in Children and Adolescents:: Identifying Eating DisordersUSFMFPNo ratings yet

- MST Nursing HandoutDocument3 pagesMST Nursing Handoutapi-261265221No ratings yet

- Research Digest: Exclusive Sneak PeekDocument11 pagesResearch Digest: Exclusive Sneak PeekIvan PitrulliNo ratings yet

- Zandian (2007) Cause and Treatment of Anorexia NervosaDocument8 pagesZandian (2007) Cause and Treatment of Anorexia NervosaRenzo LanfrancoNo ratings yet

- Objectively Measured Sedentary Time, Physical Activity, and Metabolic RiskDocument3 pagesObjectively Measured Sedentary Time, Physical Activity, and Metabolic RiskHastuti Erdianti HsNo ratings yet

- Outcomes, Satiety, and Adverse Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms Following Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric BandingDocument8 pagesOutcomes, Satiety, and Adverse Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms Following Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric BandingAna Claudia AndradeNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition & The Older PatientDocument66 pagesMalnutrition & The Older PatientDaniel WangNo ratings yet

- 12 - Methapatara2011Document7 pages12 - Methapatara2011Sergio Machado NeurocientistaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Dietary Macronutrient Distribu PDFDocument18 pagesImpact of Dietary Macronutrient Distribu PDFUdien Jmc Tíga TìgaNo ratings yet

- Akbar Aly 2009Document7 pagesAkbar Aly 2009Gitdistra Cøøl MusiçiañsNo ratings yet

- Mount Carmel College: Sara Athar MA171256 B.A. HonsDocument21 pagesMount Carmel College: Sara Athar MA171256 B.A. HonsSara AtharNo ratings yet

- Beneficial Effects of Viscous Dietary Fiber From Konjac-Mannan in Subjects With The Insulin Resistance Syndro M eDocument6 pagesBeneficial Effects of Viscous Dietary Fiber From Konjac-Mannan in Subjects With The Insulin Resistance Syndro M eNaresh MaliNo ratings yet

- 2023 - Association Between PA - SB - and Physical Fitness in HbA1c in Youth W T1DMDocument13 pages2023 - Association Between PA - SB - and Physical Fitness in HbA1c in Youth W T1DMEnoque RosaNo ratings yet

- Eating ProblemsDocument4 pagesEating ProblemsximerodriguezcNo ratings yet

- Effects of An Intensive Short-Term Diet and Exercise Intervention: Comparison Between Normal-Weight and Obese ChildrenDocument6 pagesEffects of An Intensive Short-Term Diet and Exercise Intervention: Comparison Between Normal-Weight and Obese ChildrenBudiMulyana0% (1)

- Rakel: Textbook of Family Medicine, 7th Ed.Document4 pagesRakel: Textbook of Family Medicine, 7th Ed.Nicolás Rojas MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Eating ProblemsDocument4 pagesEating ProblemsNicolás Rojas MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 12 00932 v2Document16 pagesNutrients 12 00932 v2Mario CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Calorie Restriction Non Obese IndividualsDocument10 pagesCalorie Restriction Non Obese IndividualsBeatriz VallinaNo ratings yet

- 2015 Sup 11 FullDocument5 pages2015 Sup 11 FullsebastianNo ratings yet

- Bello Haas Et Al 2013 Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1Document3 pagesBello Haas Et Al 2013 Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1ArielNo ratings yet

- DDDD DDDD DDDD DDDD DDDD DDocument1 pageDDDD DDDD DDDD DDDD DDDD DAroNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Characteristics of Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in Nanchang, China: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesEpidemiological Characteristics of Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in Nanchang, China: A Retrospective StudyAroNo ratings yet

- GCHVJKDocument1 pageGCHVJKAroNo ratings yet

- Eeeee EeeeeeeeeeeeeeeDocument1 pageEeeee EeeeeeeeeeeeeeeAroNo ratings yet

- A Novel Prion Disease Associated With Diarrhea and Autonomic NeuropathyDocument11 pagesA Novel Prion Disease Associated With Diarrhea and Autonomic NeuropathyAroNo ratings yet

- Ok Ok Ok Ooo Ooookkkkk KDocument1 pageOk Ok Ok Ooo Ooookkkkk KAroNo ratings yet

- TT TTTTT TTTTT TTTTTDocument1 pageTT TTTTT TTTTT TTTTTAroNo ratings yet

- 22380488Document11 pages22380488AroNo ratings yet

- A A LalalalaDocument1 pageA A LalalalaAroNo ratings yet

- Unu UuuuuuuDocument1 pageUnu UuuuuuuAroNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Phonophoresis On Electrophysiological Studies of The Patients With Carpal Tunnel SyndromeDocument9 pagesThe Efficacy of Phonophoresis On Electrophysiological Studies of The Patients With Carpal Tunnel SyndromeAroNo ratings yet

- Pro09 22Document6 pagesPro09 22AroNo ratings yet

- AaaaaaaDocument1 pageAaaaaaaAroNo ratings yet

- Eula Microsoft Visual StudioDocument3 pagesEula Microsoft Visual StudioqwwerttyyNo ratings yet

- DFZGZDFDocument1 pageDFZGZDFAroNo ratings yet

- Read Me! Credit! Password! Anything!Document1 pageRead Me! Credit! Password! Anything!masruri123No ratings yet

- PDFSig QFormal RepDocument1 pagePDFSig QFormal Repanon-549999100% (2)

- Put Unused Plug-Ins in The Optional Directory.Document1 pagePut Unused Plug-Ins in The Optional Directory.andias04No ratings yet

- Eula Microsoft Visual StudioDocument3 pagesEula Microsoft Visual StudioqwwerttyyNo ratings yet

- Minimal Access Surgery Compared With MedicalDocument11 pagesMinimal Access Surgery Compared With MedicalAroNo ratings yet

- AmenorrheaDocument16 pagesAmenorrheaAroNo ratings yet

- Heller's Myotomy vs. Balloon DilationDocument10 pagesHeller's Myotomy vs. Balloon DilationHeather PoushayNo ratings yet

- Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery-2007-Baez-411-7Document8 pagesJournal of Feline Medicine and Surgery-2007-Baez-411-7AroNo ratings yet

- Similac FeedingladderDocument1 pageSimilac FeedingladderAmit SonwaniNo ratings yet

- Home Remedies For HypothyroidismDocument8 pagesHome Remedies For HypothyroidismPrasadNo ratings yet

- ADA Guideline - Chronic Kidney Disease Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice GuidelineDocument19 pagesADA Guideline - Chronic Kidney Disease Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice GuidelineJorge SánchezNo ratings yet

- Content Approved For The PhilippinesDocument30 pagesContent Approved For The PhilippinesGlaiza May Mejorada PadlanNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Benefits: This Parcel of Vegetable Is Nutrient-Packed and Low in Calorie. It IsDocument10 pagesNutritional Benefits: This Parcel of Vegetable Is Nutrient-Packed and Low in Calorie. It IsEdel MartinezNo ratings yet

- Vitamin B1 & B2Document29 pagesVitamin B1 & B2BSBC Heve2016100% (1)

- IOC Nutrition ConsensusDocument19 pagesIOC Nutrition Consensusdredogg9No ratings yet

- Fibrous Protein or ScleroproteinDocument4 pagesFibrous Protein or ScleroproteinMia DimagibaNo ratings yet

- WaterleafDocument2 pagesWaterleafGILBERTNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument8 pagesDrug Studymaryhiromi10No ratings yet

- 21 Day Bowling Pin ForearmsDocument10 pages21 Day Bowling Pin ForearmsGautham DxNo ratings yet

- FRUCTE Date Nutritionale WWW - Ghidnutritie.ro Articol Fructe MangoDocument3 pagesFRUCTE Date Nutritionale WWW - Ghidnutritie.ro Articol Fructe MangotitutzaNo ratings yet

- ZZ Chapter 2Document6 pagesZZ Chapter 2Vanessa Yvonne GurtizaNo ratings yet

- Apricot Health Benefits and Nutrition FactsDocument7 pagesApricot Health Benefits and Nutrition FactsVijay BhanNo ratings yet

- Global Rally 2013 Rich List 35 Years: May 2013 - Issue 243Document36 pagesGlobal Rally 2013 Rich List 35 Years: May 2013 - Issue 243Flo BiliNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts in Sport NutritionDocument56 pagesCurrent Concepts in Sport NutritionJulioNo ratings yet

- Gut Detox Jumpstart ProgramDocument6 pagesGut Detox Jumpstart ProgramZach Trowbridge100% (1)

- Instant NoodlesDocument11 pagesInstant NoodlesBryan LeeNo ratings yet

- FON241 Essay QuestionsDocument3 pagesFON241 Essay Questionsatarisgurl080% (1)

- Food Preparation Evaluation Guide: Olivarez College Tagaytay College of NursingDocument2 pagesFood Preparation Evaluation Guide: Olivarez College Tagaytay College of NursingRaquel M. MendozaNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 Student's BookDocument174 pagesGrade 10 Student's BookMuuammadNo ratings yet

- Recommended Energy and Nutrient Intakes Per Day For FilipinosDocument1 pageRecommended Energy and Nutrient Intakes Per Day For FilipinosSarah Jane MaganteNo ratings yet

- Nutrition 101Document7 pagesNutrition 101api-168454738No ratings yet

- IDNT, 3rd Ed.Document5 pagesIDNT, 3rd Ed.Edith SungNo ratings yet

- Calcium MetabolismDocument28 pagesCalcium MetabolismAhmedkhaed100% (1)

- Materi 4 Sehat 5 SempurnaDocument3 pagesMateri 4 Sehat 5 SempurnaMuhammad RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Integrated Management of Acute MalnutritionDocument65 pagesIntegrated Management of Acute MalnutritionMousham G Mhaskey100% (3)

- 0049 Glucosamine ApplicationNote PW PDFDocument4 pages0049 Glucosamine ApplicationNote PW PDFFábio Teixeira da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Nutri Thali - Corporate PresentationDocument19 pagesNutri Thali - Corporate PresentationNikhil KurugantiNo ratings yet

- 2006 Vegetarian Diets - Nutritional Considerations For AthletesDocument14 pages2006 Vegetarian Diets - Nutritional Considerations For AthletesAni Fran SolarNo ratings yet

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1145)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1458)

- Summary of The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy FerrissFrom EverandSummary of The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy FerrissRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (81)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1135)

- The Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutFrom EverandThe Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (131)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingFrom EverandNo Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (175)

- The Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Newborn Baby Sleep LongerFrom EverandThe Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Newborn Baby Sleep LongerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Peaceful Sleep Hypnosis: Meditate & RelaxFrom EverandPeaceful Sleep Hypnosis: Meditate & RelaxRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (142)

- Neville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!From EverandNeville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (284)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Forever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy for Aging WellFrom EverandForever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy for Aging WellNo ratings yet

- How to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayFrom EverandHow to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Summary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Gut Health Hacks: 200 Ways to Balance Your Gut Microbiome and Improve Your Health!From EverandGut Health Hacks: 200 Ways to Balance Your Gut Microbiome and Improve Your Health!Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- Summary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- Love Yourself, Heal Your Life Workbook (Insight Guide)From EverandLove Yourself, Heal Your Life Workbook (Insight Guide)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (40)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- Summary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietFrom EverandSummary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)