Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Low-Wage Work Uncertainty Often Traps Low-Wage Workers

Uploaded by

Capital Public Radio0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

712 views2 pagesLow-wage workers know they have to enhance their skills to escape low-wage jobs, but long hours and multiple jobs make skill-building and education nearly impossible, according to a new policy brief released by the Center for Poverty Research at the University of California, Davis.

Original Title

Low-wage Work Uncertainty often

Traps Low-wage Workers

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLow-wage workers know they have to enhance their skills to escape low-wage jobs, but long hours and multiple jobs make skill-building and education nearly impossible, according to a new policy brief released by the Center for Poverty Research at the University of California, Davis.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

712 views2 pagesLow-Wage Work Uncertainty Often Traps Low-Wage Workers

Uploaded by

Capital Public RadioLow-wage workers know they have to enhance their skills to escape low-wage jobs, but long hours and multiple jobs make skill-building and education nearly impossible, according to a new policy brief released by the Center for Poverty Research at the University of California, Davis.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

About the Center

Over the past 50 years, the U.S. has

experienced a rising standard of

living without reducing the fraction of

the population that live in poverty. In

response to this, the Center for Poverty

Research at UC Davis is one of three

federally designated National Poverty

Centers whose mission is to facilitate non-

partisan academic research on poverty

in the U.S., to disseminate this research,

and to train the next generation of

poverty scholars. Our research agenda

spans four themed areas of focus:

n Labor Markets and Poverty

n Children and the

Intergenerational Transmission of

Poverty

n The Non-traditional Safety Net,

focusing on health and education

n The Relationship Between Poverty

and Immigration

The Center was founded in the fall of

2011 with core funding from the Offce

of the Assistant Secretary for Planning

and Evaluation in the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

For more information, email us at

povertycenter@ucdavis.edu or visit

us online at: poverty.ucdavis.edu

UC Davis Center for Poverty Research:

One Shields Avenue: Davis, CA 95616

(530) 752-0401

To download the full research study, visit poverty.ucdavis.edu

Low-wage Work Uncertainty often

Traps Low-wage Workers

By Victoria Smith and Brian Halpin, UC Davis

Some policy analysts, policymakers and scholars argue that low-wage workers

should work their way out of poverty by acquiring the human capital that would

enable them to leave poverty-level jobs.

A new study interviewing 25 low wage immigrant workers by Center for Poverty

Research Affliates Vicki Smith and Brian Halpin fnds that while many of these

low-wage workers recognize the need to enhance their skills and educational

credentials, the conditions of their employment trap them, making it nearly impossible

to escape.

Research about turbulent employment

in todays economy often focuses on

how people keep up their ability to fnd

new jobs. Steps people take to improve

their employability include acquiring

new skills, continual learning and taking

advantage of personal networks. Most

research on employability has focused

on well-paid professionals who have high

levels of human capital and considerable

labor market leverage. Research is

scarce on low-wage workers attitudes

about maintaining employability and

their efforts to increase their human

capital in light of job precariousness.

In this study, researchers examine

the efforts these workers make to stay

employable and to move out of low-wage

jobs. Interviews conducted for this

project reveal that erratic scheduling,

low pay and arbitrary managerial

treatment leave these workers unable

to improve their employability for

better-paid and higher-skilled jobs.

Precarious low-wage work forces

them to maximize the number of paid

work hours they can fnd in similar

occupational niches and limits the time

they have to search for different and

better work. This study supports the call

to improve the conditions of low-wage

work.

1

1

Paul Osterman and Beth Shulman. 2011. Good

Jobs America: Making Work Better for Everyone.

Russell Sage Foundation.

Volume 2, Number 9

Key Findings

n The precariousness of low-wage employment limits these workers time to

search for better jobs, learn new skills, take classes or obtain credentials.

n Low-wage workers in this study put considerable effort into maximizing paid

hours with multiple jobs, additional one-time jobs, working overtime without

overtime compensation, guarding their reputations and continually scanning

for opportunities within their networks.

n The barriers to building human capital suggest that policy makers should

focus on improving the conditions of low-wage work rather than expecting

workers to move out of this labor market on their own.

Funding for this project was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Offce of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Analysis (ASPE). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily refect the offcial policies of the Department of Health and Human Services.

constricted in pursuing this dream. They describe ways they

endeavor to maintain good reputations with their employers,

which enhances the likelihood they will be given more hours

and be recommended for other opportunities.

A Productive, High-quality Workforce

Low-wage workers can be a productive, high-quality

workforce despite lacking the human capital of more highly

educated, professional workers. Research repeatedly fnds

that these workers hold strong work ethics, desire stable

employment and are willing to learn but fnd it diffcult to

escape the low-wage labor market. Worker and labor market

advocates should educate employers about the benefts of

guaranteeing stable and adequate schedules rather than

subjecting them to arbitrary and erratic work hours, or

overtime hours without enhanced overtime pay.

Raising the minimum wage or introducing living wages

could create more possibilities for workers to support

themselves and their families on full-time work while

potentially freeing up time to develop their human capital.

This could also increase effciency and productivity for the

economy as a whole. This might be possible with the recent

decision to raise the minimum wage in California to $10 an

hour by 2016. Californias AB 241, the Domestic Workers Bill

of Rights, which requires overtime pay for in-home child care

and health care workers, could also advance this goal.

Interviewing Low-wage Workers

For this exploratory study, researchers conducted in-depth

interviews with 25 low-wage workers in the Napa/Sonoma

area in the fall of 2012. Interviewees were drawn from

several sectors, including food service (13), landscaping (9),

domestic work and offce cleaning (6) and construction (6).

Some interviewees worked in multiple sectors.

Interviewees were frst and 1.5 generation

2

immigrants.

They were obtained through chain referral (snow ball)

sampling. Interviewees were asked to enumerate all jobs

held in the previous fve years, to describe current jobs, how

they found jobs, how they gained skills, their short- and long-

term job plans, whether and how they utilized friendship and

kin networks to gain information and fnd jobs, barriers they

faced to upward mobility as well as steps they had taken to

gain new skills, take courses and improve their employability.

The Precariousness of Low-wage Jobs

Low-wage employment is often erratic and precarious,

limiting workers ability to learn new skills and search for

better jobs. Typically, low-wage jobs are part-time with

no guaranteed hours, making it diffcult for individuals to

manage time effectively across work and non-work areas of

their lives. Many employers expect workers to be on-call and

available if needed, even sometimes for 12-hour shifts without

advanced notice. This uncertainty leaves workers vulnerable

to the capriciousness of management and often unable to

have any control over their schedules. This makes it extremely

diffcult for these workers to take advantage of education and

training opportunities which require scheduled attendance.

To cope and sustain their economic livelihoods, these

workers focus on maintaining the jobs they have while

searching for additional opportunities through relatives,

friends and occupational networks. They piece together

multiple full- and part-time jobs, often endeavoring to

distribute jobs across time to maximize their paid hours.

For example, they will defer a request from an employer,

stagger jobs, and continually scan their networks for news of

additional one-time job opportunities.

Horizontal Mobility and a Regular Job

Many interviewees described how they attempted to learn

new skills in their current occupational niche when possible,

such as a housecleaner learning how to clean offces, or a

worker who sets up tables and chairs at events for a catering

company learning how to make special desserts. However,

these new skills often offer horizontal but not vertical mobility.

Low-wage workers interviewed for this project said

they would prefer stable long-term jobs with stable work

hours. In other words, like many workers today they yearn

for a regular job. Unlike many workers, they are highly

2

Generation 1.5 refers to immigrants who arrived as children before

adolescence.

3

John Schmitt and Janelle Jones. 2012. Low-wage Workers are Older and

Better Educated than Ever. Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Meet the Researchers

Victoria Smith is a Professor of Sociology at UC Davis and a Center for Poverty

Research Faculty Affliate. She studies changes in the organization of work, in

employment relationships, and in job searching strategies.

Brian Halpin is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at UC Davis and the 2011

recipient of the Mayhew Award for an Outstanding Graduate Student Paper. He

studies Labor Markets, Political Economy and Ethnography.

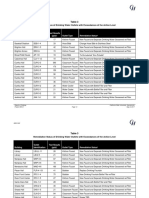

Characteristics of low-wage workers in the

U.S. in 2011

3

n Average age is 34.9 years old.

n Over 38% of these workers are between 35 and 64

years old.

n 33.3% have some college education.

n 55% are women and 45% are men.

n 56.9% are white, 23% are Latino, and 14.3% are

black.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- 2019-2020 California Budget ProposalDocument280 pages2019-2020 California Budget ProposalCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Amendments To SB 10 - Bail Reform BillDocument18 pagesAmendments To SB 10 - Bail Reform BillCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- California Budget Summary 2018-19Document272 pagesCalifornia Budget Summary 2018-19Capital Public Radio100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- New Deputy Secretary For Human ResourcesDocument1 pageNew Deputy Secretary For Human ResourcesCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- ISIS Terrorist Omar Ameen - US Detention and Extradition MemoDocument32 pagesISIS Terrorist Omar Ameen - US Detention and Extradition MemoThe Conservative Treehouse100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Termination LetterDocument1 pageTermination LetterCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 107-1-Ms. L Status Report - Meekins DeclarationDocument17 pages107-1-Ms. L Status Report - Meekins DeclarationCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Inspector General Report On Shooting of Mike McIntyreDocument27 pagesInspector General Report On Shooting of Mike McIntyreCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Ameen Criminal ComplaintDocument94 pagesAmeen Criminal ComplaintCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Sandeep Rehal Lawsuit Against WeinsteinDocument11 pagesSandeep Rehal Lawsuit Against WeinsteingmaddausNo ratings yet

- DutyStatmt OrgChartDocument2 pagesDutyStatmt OrgChartCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Senate HR Job PostingDocument1 pageSenate HR Job PostingCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Creative Economy Fact SheetDocument9 pagesCreative Economy Fact SheetCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Dababneh Resignation Letter FinalDocument2 pagesDababneh Resignation Letter FinalCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Really Large Guide To Live Jazz Events (Updated 9/5)Document22 pagesReally Large Guide To Live Jazz Events (Updated 9/5)Capital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- SB 54 Signing Message 2017Document1 pageSB 54 Signing Message 2017Capital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Really Large Guide To Live Jazz EventsDocument29 pagesReally Large Guide To Live Jazz EventsCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- East Area Rapist Stolen ItemsDocument5 pagesEast Area Rapist Stolen ItemsCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- California DOJ URSUS 2016 ReportDocument68 pagesCalifornia DOJ URSUS 2016 ReportCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- City of Sacramento City Hall Visitor PolicyDocument2 pagesCity of Sacramento City Hall Visitor PolicyCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CapRadio's Really Large Guide To Live Jazz EventsDocument21 pagesCapRadio's Really Large Guide To Live Jazz EventsCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Justice Assistance Grant Complaint - CaliforniaDocument25 pagesJustice Assistance Grant Complaint - CaliforniaCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Remediation Status of Drinking Water Outlets With Exceedances of The Action LevelDocument3 pagesRemediation Status of Drinking Water Outlets With Exceedances of The Action LevelCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Claims Form - Government Claims Program - Office of Risk and Insurance ManagementDocument5 pagesClaims Form - Government Claims Program - Office of Risk and Insurance ManagementCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- FY2017-18 Master Fee Schedule Citywide Fees and Charges UpdateDocument21 pagesFY2017-18 Master Fee Schedule Citywide Fees and Charges UpdateCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- UC Regents' LetterDocument2 pagesUC Regents' LetterCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Invoice Letter, Summary Report, and ROEDocument10 pagesInvoice Letter, Summary Report, and ROECapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Lead Concentration of The Drinking Water For Each Outlet SampledDocument12 pagesLead Concentration of The Drinking Water For Each Outlet SampledCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Remediation Status of Drinking Water Outlets With Exceedances of The Action LevelDocument3 pagesRemediation Status of Drinking Water Outlets With Exceedances of The Action LevelCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- May Revise - Full Budget SummaryDocument92 pagesMay Revise - Full Budget SummaryCapital Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Topic 10 Leading and Managing ChangeDocument15 pagesTopic 10 Leading and Managing Change1dieyNo ratings yet

- Band 6 Nurse Interview Guide: 5 Common Questions AnsweredDocument6 pagesBand 6 Nurse Interview Guide: 5 Common Questions AnsweredGianina Avasiloaie0% (1)

- Issues, Challenges and Prospects of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (Smes) in Port-Harcourt City, NigeriaDocument14 pagesIssues, Challenges and Prospects of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (Smes) in Port-Harcourt City, NigeriarexNo ratings yet

- Administrative Officer RésuméDocument4 pagesAdministrative Officer RésuméEnggel BernabeNo ratings yet

- Field ReportDocument17 pagesField Reportshafiru khassimuNo ratings yet

- Plant Isolation, Safety Tag and Lockout ProceduresDocument8 pagesPlant Isolation, Safety Tag and Lockout ProceduresiuiuiooiuNo ratings yet

- Upload Us1 PDFDocument144 pagesUpload Us1 PDFErickAlmoraxdAncasi78% (9)

- Shell Co. V VanoDocument1 pageShell Co. V VanoLouNo ratings yet

- 1st Set Labstand Case Digests - UsitaDocument13 pages1st Set Labstand Case Digests - UsitaLyssa Tabbu100% (1)

- WhatMotivatesGenerationZatWork PDFDocument13 pagesWhatMotivatesGenerationZatWork PDFpreeti100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- DelegationDocument4 pagesDelegationThandie MizeckNo ratings yet

- Privatisation Question (CHONG ZHENG YANG)Document3 pagesPrivatisation Question (CHONG ZHENG YANG)dss sdsNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Work EthicsDocument52 pagesLesson 2 Work EthicsAlex Nalogon TortozaNo ratings yet

- Uthaman Et Al 2015 Older Nurses A Literature Review On Challenges Factors in Early Retirement and Workforce RetentionDocument6 pagesUthaman Et Al 2015 Older Nurses A Literature Review On Challenges Factors in Early Retirement and Workforce RetentionLynnie Dale CocjinNo ratings yet

- IRF Form PDFDocument1 pageIRF Form PDFhimanshu jain100% (1)

- Tvet ScriptDocument4 pagesTvet ScriptEBUENGA, Raymarc Brian R.No ratings yet

- The Brazilian System For The Solidarity Culture - Fora Do Eixo CardDocument9 pagesThe Brazilian System For The Solidarity Culture - Fora Do Eixo CardHelyi PénzNo ratings yet

- 2020 WEC Handbook Revised March 6 2020Document77 pages2020 WEC Handbook Revised March 6 2020Wes .MNo ratings yet

- Arti's Project of HR - Vijan Mahal Final CompleetioDocument56 pagesArti's Project of HR - Vijan Mahal Final CompleetioArti KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- BalmerLawrie rewards scheme guideDocument15 pagesBalmerLawrie rewards scheme guideektatiwari9No ratings yet

- Mil STD 1474dDocument107 pagesMil STD 1474draer1971No ratings yet

- Project Safety Management SystemDocument16 pagesProject Safety Management SystemrosevelvetNo ratings yet

- MEENATCHISUNDARAM KARTHIK Jul 29, 2023Document3 pagesMEENATCHISUNDARAM KARTHIK Jul 29, 2023sathishkumardsp.22No ratings yet

- 21st Century School Counselor Chap262008Document12 pages21st Century School Counselor Chap262008Wastiti AdiningrumNo ratings yet

- Australian Local Government Environment YearbookDocument156 pagesAustralian Local Government Environment Yearbookdavid_haratsisNo ratings yet

- This Is An ObliCon Reviewer Is It Not - PDFDocument154 pagesThis Is An ObliCon Reviewer Is It Not - PDFJean Jamailah TomugdanNo ratings yet

- Gen Z Workforce and Job-Hopping Intention: A Study Among University Students in MalaysiaDocument27 pagesGen Z Workforce and Job-Hopping Intention: A Study Among University Students in MalaysiangocNo ratings yet

- Neuroleadership in The Human ResourceDocument3 pagesNeuroleadership in The Human ResourceCliff KaaraNo ratings yet

- Tax AssignmentDocument5 pagesTax AssignmentdevNo ratings yet

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverFrom EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (186)

- Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsFrom EverandBillion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (52)

- Workin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherFrom EverandWorkin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherNo ratings yet

- The Five Dysfunctions of a Team SummaryFrom EverandThe Five Dysfunctions of a Team SummaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Revised and Updated: Achieving Your Wildly Important GoalsFrom EverandThe 4 Disciplines of Execution: Revised and Updated: Achieving Your Wildly Important GoalsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (48)

- Spark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessFrom EverandSpark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (130)

- The First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsFrom EverandThe First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (55)

- How to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (36)