Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Automotive History

Uploaded by

Ramesh GowdaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Automotive History

Uploaded by

Ramesh GowdaCopyright:

Available Formats

5/10/2014 Automotive History

http://bentley.umich.edu/research/guides/automotive/ 1/6

Verso: "1899-1900--St eam car built by Howard

Coffin while in College at U. of M. (Ann Arbor)

modeled on lines of Locomot ive st eamer but

wit h larger boiler and Engines (2 cyl)." Folder

"Phot o of Howard Coffin wit h st eamer car."

Box 30, Roy Dikeman Chapin papers.

Click t o enlarge.

Automotive History

OVERVIEW

Early inventors

Michigan automotive history starts in the 1890s, when inventors tinkered the idea of self-

propelled vehicles. The bicycle, which had acquired wide-spread popularity in the 1880s,

inspired auto inventors to explore the concept of self-conveying vehicles. As a result, the

earliest, successful auto parts companies had previous experience with bicycle components,

rather than wagon and carriage parts.

The desire for mobility led to two

early successes. In 1891, a man

named William Morrison,

constructed an electric carriage that

he drove through Des Moines, Iowa.

Two years later, 1893, in Springfield,

Massachusetts, Frank Duryea

exhibited a motorized truck, using an

internal combustion engine. Duryea

would later manufacture internal

combustion vehicles--13 in his first

year of operation. 1893 was also the

year in which the U.S. Office of Road

Inquiry was established (due to

pressure from bicyclists) to study

the condition of American roads and

make recommendations for

improvement. Americans were feeling

exploratory, fascinated with the idea

of traveling about the country on

independent schedules. The climate

was ripe for inventors and tinkerers; it was a matter of "who" and "when" would build a

horseless carriage, not "if."

Consumers

The first companies to produce automobiles for the public market emerged in 1896.

Surprisingly, these early auto manufucturers built more electric than gas-powered vehicles.

However, when gas-powered internal combustion engines no longer needed the help of a hand

crank to start, then the electric automobile lost ground. The 1912 Cadillac was the first vehicle to

have an effective self-starting engine.

Consumers materialized and marketing attempts began almost as soon as manufacturers knew

that they had a product to sell. In 1898, William Metzger became the country's first automobile

dealer not in the direct employ of a manufacturer with the establishment of his Detroit

dealership. Two years later, in 1900, the first National Autombile Show was held in New York

City at Madison Square Garden. Approximately 48,000 people visited the 51 exhibitors,

consisting of automobile manufacturers and parts supply companies, and saw 300 different

CONTENTS

Overview

Executives and Management

Workers and Labor Relations

Consumers and Marketing

Research and Development

Automobile Travel and Hobbyists

Journalists

Other Relevant Collections

Published Primary Sources

Visual Materials

5/10/2014 Automotive History

http://bentley.umich.edu/research/guides/automotive/ 2/6

1912 self-st art ing Cadillac. Folder "General Mot ors

Corporat ion, misc." Box 1, Jack Kausch papers.

Ca. 1904 Oldmobile out on a t est drive. Folder

"Hudson cars: Aut omobile t est ing; Aut o workers"

Box 30, Roy Dikeman Chapin papers.

Click t o enlarge.

models.

Motor City, Michigan

Though Detroit built its wealth

and reputation on the automotive

industry, Michigan didn't start

out as the auto industry capital

of the world. Rather, New

England was the birthplace of

many of the early auto

companies. However, by 1905,

Michigan had solidified its claim

as the central location of the

industry. Circumstantial

coincidences tied Michigan to the

emerging auto industry. The

state's plentiful natural resources

(timber, copper, and iron) had

been harvested and depleted, but

not before creating fortunes for

timber and mining interests.

These capitalists had excess

funds for which they were looking

for more profitable investment

opportunities at the time that

Ransom E. Olds needed capital for

his fledgling automobile company.

Two of these wealthy Michiganders,

Edward W. Sparrow and Samuel L.

Smith, forged a partnership with

Ransom Olds, creating the Olds

Motor Works. Another Michigan

resident also helped to make Detroit

the Motor City: Henry Ford. His

tenacity and innovation in the new

industry ensured the success of his

product. If Olds and Ford had been

less successful, the title of Motor

City may well have gone to some

other city. Ransom Olds and Henry

Ford were able to capture the auto market and secure Michigan's central role because of their

profitable business philosophy of "low cost, high volume."

In other to maintain low production costs, both Olds and Ford introduced the production line.

Henry Ford took the concept of the production line further, refining the actual process used to

assemble vehicles. The moving assembly line is one example of his innovations. These

improvements were able to increase the cost-effectiveness of vehicle assembly so that the

company could reduce the actual retail cost of the car.

Since 1896, it is estimated that over 1,500 automobile makers have operated in the U.S. The

sheer number of competitors has resulted in power struggles. Consequently, larger, more

powerful companies bought up smaller companies with little market share.

World War I and the 1920s

World War I forced the auto industry to slow its production; it was cut in half in order to devote

factories to war production. When WW I ended, anticipating a sudden increase in demand,

automakers flooded the market with new cars. While the surge in demand remained high for two

5/10/2014 Automotive History

http://bentley.umich.edu/research/guides/automotive/ 3/6

Lansing, MI, 1906. From L t o R: experiment al,

curved dash, 2 cylinder, and 4 cylinder models.

Scrapbook, Vol. 1, 1886-1911. Roy Dikeman

Chapin papers. Click t o enlarge.

Aut oworkers inside Buick Mot or Company, Plant 1.

Vert ical File, Flint , MI phot ograph collect ion.

Click t o enlarge.

years, an economic slump in 1920

distressed the industry because of the

excess supply and low demand. As

history demonstrates, the automobile

industry has always been sensitive to

economic conditions, like a canary in

the coal mine.

Regardless of a slow market, 1920

was a pivotal year for U.S. auto

companies. By 1920, automakers

were no longer experimenting with

design; placing the engine under the

hood became standard, as did cable

brake systems, steering wheels (as

opposed to steering rudders), and

combustion engines. At this point in

history, most people had at least

seen an automobile, even if they did

not own one themselves. Cars had

become culturally accepted and

morever, American culture began to change to accomodate these new machines.

In 1923, Alfred P. Sloan

was appointed president

of General Motors, after

serving as the company's

vice president. Sloan's

leadership was largely

responsible for GM's

decades of success; he

introduced marketing

techniques that auto

companies continue to

use. Sloan realized that

because more Americans

were becoming car

owners, the market for

first-time buyers was

shrinking; cars were no

longer novelty items.

Dealers needed to

persuade buyers that they

needed another car. The annual model was one of Sloan's marketing techniques--by changing the

cosmetic appearance of the car (and sometimes the technical features), consumers had incentives

to buy newer models, to trade up, or add a second car to the family's garage. He expressed his

strategy with the catch phrase "a car for every purse and purpose."

Price structure was another of Sloan's innovations; Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldmobile, Buick, and

Cadillac are the various GM brands, from least to most expensive. In each brand, the top of the

line of one brand costs just a little bit less than the lowest priced model of the next expensive

line. With this pricing structure, consumers could be convinced to spend a little more to

purchase a more prestigous brand of vehicle.

In the mid-twenties, Ford dropped from the nation's top automaker to second place behind

General Motors. Ford Motor Company continued to hold its second place ranking until Henry

Ford retired in 1945. In 1927, Ford's Model A was introduced to consumers. In 1928, Chrysler

acquired Dodge. By 1929, GM, Ford, and Chrysler comprised 75% of annual auto sales in the

United States.

American culture experienced extreme and irrevocable change as a result of the automobile's

entrance into modern life, beginning in the 1920s. Rural familes were no longer isolated from

5/10/2014 Automotive History

http://bentley.umich.edu/research/guides/automotive/ 4/6

The first Chevrolet aut omobile produced in Det roit , 1912.

Louis Chevrolet , st anding w/o hat . W.C. Durant , st anding,

wit h derby hat at t he right end of t he group. Cliff Durant

(W.C.'s son) at t he wheel, his wife in t he passenger seat .

Folder "Phot ographs, Aut omobiles and relat ed." Box 15,

Frank Angelo papers. Click t o enlarge.

Packard-Huron st reet railway car, ca. 1912. Folder

"AASR-AG." Box 1, Claude Thomas St oner papers.

larger communities,

which had implications

on education,

commerce, and

agriculture. Urban

Americans used their

newfound mobility to

escape the dirt, noise,

and congestion of city

life, at least

temporarily. Outdoor

pursuits, such as

camping, hunting, and

fishing gained

popularity as leisure

activities. Indebtedness

became an acceptable

part of life, both due to

the installment buying

that had been

introduced during the

early days of the

industry and later through the credit cards issued by gasoline companies.

The growth of suburban

communities was another

change that American culture

experienced; as the suburbs

grew and Americans began to

commute by car, the electric

railways and interurban trains

became obsolete. As more

Americans began to commute,

city congestion and scarce

downtown parking meant that

businesses moved to city

outskirts, where parking lots

could be built and congestion

was not a concern. Road

repairs and improvements

became a larger responsiblity for local governments; ultimately, a gas tax was levied in order to

raise the necessary funds to maintain roads. Tourism developed as a result of the auto industry--

camp sites and motor lodges, restaurants, and tourist attractions all waited to feed, clothe, and

entertain the passing motorist.

The auto industry and organized labor

The Great Depression devasted the automobile industry; the many Detroit-area workers

employed by the Big Three lost their job security and stability. During the Depression, the city

of Detroit added 300 families to the relief rolls each day; a significant number of these families

had previously been supported by the relatively high auto industry wages. The auto industry's

response to the Depression varied by company, but typically involved wage cuts, layoffs, and

increased production speed. In response to these Depression-era measures that many auto parts

suppliers instituted, strikes and walk-outs grew more frequent.

The automotive industry and the labor movement share an intertwined history. Small

tradesmens' unions were involved in the industry from its inception, but for unskilled auto

workers, it would not be until the mid-thirties that a widespread industrial union would take

hold. The industrial labor union movement in Detroit owes much of its later success to the

5/10/2014 Automotive History

http://bentley.umich.edu/research/guides/automotive/ 5/6

April 1937, Chrysler st rike resolved. Seat ed left

t o right : John L. Lewis, Murphy, Walt er Chrysler,

Dewey. St anding left t o right : Homer Mart in,

Richard Frankenst een, Lee Pressman, K. T. Keller,

Herman Weckler. Scrapbook 25, Frank Murphy

papers. Click t o enlarge.

earlier presence of the Carriage, Wagon and Automobile Workers and Industrial Workers of the

World (IWW). These two union pioneers tried a new approach with automotive workers. While

the trade unions already operating united skilled craftsmen, the IWW and the Carriage, Wagon

and Automobile Workers were the first to attempt to organize the industry, creating a union that

was open to all workers, regardless of trade or skill level. In 1936, the newly organized United

Automobile Workers with the Congress of Industrial Organizations enforced a sit-down strike at

GM plants in Flint, MI.

By February 1937, GM recognized

the UAW as the bargaining agent

for its workers. Chrysler

recognized UAW shortly after GM

did. However, at Ford, the UAW

and other unions were not able to

organize until 1941.

Post-WWII

World War II affected the auto

industry much like the first World

War; auto production slowed and

stopped in order to provide factory

space and ensure adequate

materials for war production. But

after the war, from 1945 to 1950,

the industry enjoyed a healthy

period. Models moved quickly out of showrooms. Even until the 1980s, the Big Three

experienced steady growth and healthy profits. Starting in the 1950s, environmental concerns

developed a more forceful voice, and vehicle emissions legislation was passed by Congress.

Safety concerns also led to the passage of seatbelt laws.

1966 witnessed the passage of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, the Highway

Safety Act, as well as the creation of the Department of Transportation. During the 1960s, the

industry rediscovered its electric origins, toying with the idea of electric vehicles. General

Motors developed protypes of two electric vehicles, the Electrovan and the Electrovair II, an

electric version of the Corvair. American Motors Company, a decade later, would market electric

Jeep vehicles, the Electruck, to the U.S. Postal Service.

During the 1975 fuel crisis, Congress passed the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) bill

which required automakers to increase the fuel efficiency of their passenger car fleet.

Consequently, the Big Three began to make smaller cars for sale in the U.S. during the 1980s.

The 1980s also saw the growth of the import market; instead of merely competing against each

other, the Big Three now had to contend with fuel-efficient vehicles from Germany and Japan.

Imports sold surprisingly well. Toyota emerged as the foreign leader, harnessing the majority of

the import market share.

As more and more members of the American public purchased vehicles, second-car ownership

became common. Increasingly, each individual owned a car, in contrast to the earlier trend of the

"family car." In some homes, there could be as many cars as there were licensed drivers.

The invention and re-invention of the automobile industry has impacted American society like

nothing else. As the industry continues to evolve during dark economic times, research into the

origins and past directions of the auto industry takes on an added significance.

About this guide

Arranged topically, this subject guide aims to help researchers identify collections useful for

their research interests. The topical categories contain a combination of manuscript collections

and organizational records. This subject guide represents the bulk of the Bentley Historical

Library's automotive history holdings and includes the most content-heavy collections.

Additional materials with small portions of relevant items may be discovered with a MIRLYN

search.

5/10/2014 Automotive History

http://bentley.umich.edu/research/guides/automotive/ 6/6

Cadillac Mot or Company. Folder "General Mot ors

Corporat ion, misc." Box 1, Jack Kausch papers.

Executives and Management includes collections from automobile industry executives,

management personnel, as well as several motor companies' administrative records.

Workers and Labor Relations directs researchers to collections that document the auto

worker's experience, labor regulatory bodies, and individuals and organizations that studied

and/or supported auto industry workers.

Consumers and

Marketing contains

collections that document

the buying and selling of

automobiles, with trade

catalogs and the personal

papers of Michigan auto

dealers.

Research and

Development identifies

collections that pertain to

auto industry research and

analysis activities, as well

as the development of new

technologies.

Automobile Travel and

Hobbyists includes

manuscript documentation

of cross-country auto travel, as well as Michigan automobile clubs.

Other Relevant Collections consists of collections that contain related material, but are not

strictly within to the automobile industry. The papers of politicians who worked to pass vehicle

emissions and safety standards, journalists, as well as architects and city planners who designed

parking lots and structures are among the collections represented in this area of the subject guide.

Published Primary Sources includes a selection of books, serials, and audio recordings that

date from the first few decades of the industry. For additional published materials, please

conduct a MIRLYN search.

Visual materials contains photo collections and motion picture films that document some

aspect of the auto industry, including gas stations, auto accidents, and early automobile models.

Return to the top

References

Automobile Manufacturers Association. Automobiles of America, 2nd ed. 1968. Detroit: Wayne State

University Press.

May, Geoge S., Ed. The Automobile industry, 1896-1920. 1990. New York: Facts on File.

May, Geoge S., Ed. The Automobile industry, 1920-1980. 1989. New York: Facts on File.

Peterson, Joyce Shaw. American automobile workers, 1900-1933. 1987. Albany: SUNY Press.

Developed by Rachael Dreyer, Graduate Reference Assistant, July 2009.

1150 Beal Avenue Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2113 U.S.A. | 734.764.3482 | Fax: 734.936.1333

Reference: bentley.ref@umich.edu | Webmaster: bhlwebmaster@umich.edu

University of Michigan

Last modified: July 05, 2007 4:22:03 PM EDT.

Banner image from Jasper Cropsey' s The University of Michigan Campus, 1855

You might also like

- Automotive History Subject GuideDocument45 pagesAutomotive History Subject GuideMohamed Abd ElhafizNo ratings yet

- English Cars EssayDocument5 pagesEnglish Cars EssayShannon ChoiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Industry: Chapter OneDocument82 pagesIntroduction To The Industry: Chapter OneAakashSharmaNo ratings yet

- Final Year PROJECTDocument48 pagesFinal Year PROJECTZaint0p GamingNo ratings yet

- Car IndustryDocument32 pagesCar IndustryMohammad HagigiNo ratings yet

- American Car CultureDocument3 pagesAmerican Car CultureTimi CsekkNo ratings yet

- Impact of Cars On SocietyDocument20 pagesImpact of Cars On SocietyAman SadanaNo ratings yet

- History of The American Car IndustryDocument23 pagesHistory of The American Car IndustryIuditm-Zsuzsi VigNo ratings yet

- Rahuman BBA ProjectDocument82 pagesRahuman BBA ProjectjithuNo ratings yet

- 1920s Automobile EssayDocument5 pages1920s Automobile Essayapi-577089791No ratings yet

- Henrey FordDocument6 pagesHenrey FordAnshu KNo ratings yet

- Lecture 02 ItM Ford Vs Sloan Case MN302Class3Document4 pagesLecture 02 ItM Ford Vs Sloan Case MN302Class3Sayonee Choudhury100% (1)

- Describe The Car IndustryDocument3 pagesDescribe The Car IndustryLillian KobusingyeNo ratings yet

- IC. A1.1 - Mar26 - Case. Automotive IndustryDocument9 pagesIC. A1.1 - Mar26 - Case. Automotive IndustryMinh Anh PhạmNo ratings yet

- The Rise of AutomobilesDocument7 pagesThe Rise of Automobilesapi-3776005No ratings yet

- Group Project Brief: Submission Format and InstructionsDocument10 pagesGroup Project Brief: Submission Format and InstructionsNguyễn Viết NhậtNo ratings yet

- Introduction About Automobiles IndustryDocument12 pagesIntroduction About Automobiles IndustrybasavtejaNo ratings yet

- b3 Nurayda Albeez Effects of Automobiles On American Culture 2Document6 pagesb3 Nurayda Albeez Effects of Automobiles On American Culture 2api-616433899No ratings yet

- Influence of Social Media InteractionDocument70 pagesInfluence of Social Media InteractionMithun Reddy100% (1)

- The Jazz Age 1920'sDocument7 pagesThe Jazz Age 1920'slileinNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document12 pagesLesson 2niroshan24No ratings yet

- Industry Profile of AutomobilesDocument6 pagesIndustry Profile of AutomobilesJinu SekerNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Auto Museum and Antique Town, Murdo, South DakotaFrom EverandPioneer Auto Museum and Antique Town, Murdo, South DakotaNo ratings yet

- The Fastest Cars in History 1914Document101 pagesThe Fastest Cars in History 1914Johann NunweilerNo ratings yet

- 高频文章20 汽车的历史【拼多多店铺:好课程】Document4 pages高频文章20 汽车的历史【拼多多店铺:好课程】LingYan LyuNo ratings yet

- Mahindra and MahindraDocument58 pagesMahindra and MahindraMukesh ManwaniNo ratings yet

- What Was The Original Problem (S) That The Automobile Was Supposed To Solve?Document9 pagesWhat Was The Original Problem (S) That The Automobile Was Supposed To Solve?Angel LagmayNo ratings yet

- Story of the Automobile: Its history and development from 1760 to 1917. With an analysis of the standing and prospects of the automobile industryFrom EverandStory of the Automobile: Its history and development from 1760 to 1917. With an analysis of the standing and prospects of the automobile industryNo ratings yet

- Ford AnalysisDocument11 pagesFord AnalysisbricekenneNo ratings yet

- 1 - Electric and Hybrid Cars - A History BookDocument39 pages1 - Electric and Hybrid Cars - A History BookHubert CelisNo ratings yet

- Automobile Industry: Idustry HistoryDocument2 pagesAutomobile Industry: Idustry HistoryFatma MusallamNo ratings yet

- The Upside of Turbulence: Seizing Opportunity in an Uncertain WorldFrom EverandThe Upside of Turbulence: Seizing Opportunity in an Uncertain WorldRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Split Personalities of FordDocument20 pagesSplit Personalities of FordVlad Matei100% (1)

- Farrell - Marie-Ange - The Gasoline Station in The American LandscapeDocument15 pagesFarrell - Marie-Ange - The Gasoline Station in The American LandscapeFarrellNo ratings yet

- Car Collector Chronicles 03-16Document5 pagesCar Collector Chronicles 03-16Dave YarosNo ratings yet

- 13 Chapter 4Document25 pages13 Chapter 4yousefzkrNo ratings yet

- Comeback: The Fall & Rise of the American Automobile IndustryFrom EverandComeback: The Fall & Rise of the American Automobile IndustryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The History of The Automobile 1Document42 pagesThe History of The Automobile 1Sharma KawalNo ratings yet

- AutoDocument26 pagesAutozzxxcczNo ratings yet

- English Car Invention PowerpointDocument2 pagesEnglish Car Invention PowerpointgearNo ratings yet

- Nissan FinalDocument66 pagesNissan Finalapi-3746231100% (1)

- Automotive History 1Document3 pagesAutomotive History 1Neil DholabhaiNo ratings yet

- The History of The AutomobileDocument10 pagesThe History of The AutomobilesorinadanNo ratings yet

- Geared-Up Faith for Classic Car Buffs: Devotions to Help You Reflect, Recharge, and RestoreFrom EverandGeared-Up Faith for Classic Car Buffs: Devotions to Help You Reflect, Recharge, and RestoreNo ratings yet

- XL Dynamics Financial Analyst Interview Questions - Glassdoor - CoDocument5 pagesXL Dynamics Financial Analyst Interview Questions - Glassdoor - CoRamesh Gowda100% (3)

- I Need Free Serial Key of Acrobat Xi Pro - FixyaDocument3 pagesI Need Free Serial Key of Acrobat Xi Pro - FixyaRamesh Gowda33% (3)

- Sample Resume For MBA FresherDocument3 pagesSample Resume For MBA FresherRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Accounts Payable Interview QuestionsDocument11 pagesAccounts Payable Interview QuestionsBandita RoutNo ratings yet

- Investment Banking Practice InterviewDocument10 pagesInvestment Banking Practice InterviewRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Ipsr JobsDocument5 pagesIpsr JobsRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Assistant Manager - Deputy Manager Financial Accounting Rbin - BSV - Bengaluru - Bangalore - Bosch Limited - 3-To-5 Years of ExperienceDocument3 pagesAssistant Manager - Deputy Manager Financial Accounting Rbin - BSV - Bengaluru - Bangalore - Bosch Limited - 3-To-5 Years of ExperienceRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Company Profile 38888Document3 pagesCompany Profile 38888Ramesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Prin (Z) - Analysing Trends TheoryDocument5 pagesPrin (Z) - Analysing Trends TheoryRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting Project Reports - Google SearchDocument2 pagesCapital Budgeting Project Reports - Google SearchRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Milestone Trend Analysis (MTA)Document2 pagesMilestone Trend Analysis (MTA)Ramesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Slideshare For Android. 15 Million Presentations at Your FingertipsDocument6 pagesSlideshare For Android. 15 Million Presentations at Your FingertipsRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Trend Analysis Project Report - Google SearchDocument2 pagesTrend Analysis Project Report - Google SearchRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- NotesBowl - College Notes - Academic Projects - Question BankDocument4 pagesNotesBowl - College Notes - Academic Projects - Question BankRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Robert Bosch Company Profile 37884Document4 pagesRobert Bosch Company Profile 37884Ramesh Gowda0% (1)

- W62 How Do CFOsDocument36 pagesW62 How Do CFOsRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- LRDocument2 pagesLRRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Bosch India Foundation 2013Document28 pagesBosch India Foundation 2013Ramesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- MC ValuationDocument34 pagesMC ValuationRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Shivakumar NG - India - LinkedInDocument2 pagesShivakumar NG - India - LinkedInRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Ernst & Young - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument12 pagesErnst & Young - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Robert Bosch GMBH - Notes To The Financial Statements Principles and MethodsDocument9 pagesRobert Bosch GMBH - Notes To The Financial Statements Principles and MethodsRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Automotive Industry in India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument31 pagesAutomotive Industry in India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Robert Bosch GMBH - Statement of Financial PositionDocument2 pagesRobert Bosch GMBH - Statement of Financial PositionRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Premier Technical Support Contact InformationDocument2 pagesPremier Technical Support Contact InformationRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- 13 Chapter 4Document25 pages13 Chapter 4yousefzkrNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Comparative StudyDocument55 pagesAnalysis and Comparative StudyMaheshwar MallahNo ratings yet

- The LIAJ's Comments On Supplement To ED Financial Instruments: ImpairmentDocument8 pagesThe LIAJ's Comments On Supplement To ED Financial Instruments: ImpairmentRamesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Bosch Profile 2012 2Document54 pagesBosch Profile 2012 2Ramesh GowdaNo ratings yet

- Saab ArticleDocument2 pagesSaab ArticleChristoph HamburgNo ratings yet

- Adaptive Cruise Control in AutomobilesDocument20 pagesAdaptive Cruise Control in AutomobilesAlvin SabuNo ratings yet

- Lamborghini HuracánTecnica AHUGWS 22.10.06Document14 pagesLamborghini HuracánTecnica AHUGWS 22.10.06ssssNo ratings yet

- Hilux: GGN, TGNDocument26 pagesHilux: GGN, TGNbelkaidaNo ratings yet

- Four Wheel Steering ReportDocument8 pagesFour Wheel Steering Reportvijayan m g100% (12)

- OMC Electrical PartsDocument6 pagesOMC Electrical Partswguenon100% (1)

- Diesel ForkliftDocument2 pagesDiesel ForkliftHoàng Anh PhạmNo ratings yet

- BMW Master ThesisDocument6 pagesBMW Master Thesisdawnrobertsonarlington100% (2)

- Redi Go Launch Brochure 20 Pager 22x22 AW 01Document10 pagesRedi Go Launch Brochure 20 Pager 22x22 AW 01Lina Zidni IlmiNo ratings yet

- 2003 Peugeot 406 Break 65020Document177 pages2003 Peugeot 406 Break 65020Jimmy AlemanNo ratings yet

- Azure - Panda - Emall061202 - Zeekr - Leaflet X - A4 - EN-24Document9 pagesAzure - Panda - Emall061202 - Zeekr - Leaflet X - A4 - EN-24prestigebuild888No ratings yet

- LH514 - OkokDocument6 pagesLH514 - OkokVictor Yañez Sepulveda100% (1)

- 2013-03-08 035329 Remote StartDocument4 pages2013-03-08 035329 Remote Starttho huynhtanNo ratings yet

- Mercedes-Benz: Year Type Mat. Qty. PositionDocument45 pagesMercedes-Benz: Year Type Mat. Qty. PositionAmel AlidraNo ratings yet

- DAF XF CF Euro 4, 5 Electrical Wiring DiagramsDocument199 pagesDAF XF CF Euro 4, 5 Electrical Wiring DiagramsgsmhelpeveshamNo ratings yet

- RecordsDocument39 pagesRecordsMohit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Caja Allison 4700Document2 pagesCaja Allison 4700Claudio Duran Caballero50% (2)

- Technical Specification/Customer Input Sheet: Yes/No Yes/NoDocument2 pagesTechnical Specification/Customer Input Sheet: Yes/No Yes/NospdhimanNo ratings yet

- Axia 2023Document1 pageAxia 2023suhayl azlanNo ratings yet

- Service BillDocument1 pageService Billharshdewangan113No ratings yet

- Ninebot Max Series Brochure 0212 - enDocument35 pagesNinebot Max Series Brochure 0212 - enimsocuriousNo ratings yet

- Getrag En1 PDFDocument6 pagesGetrag En1 PDFJeremías EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Readme RusDocument2 pagesReadme RusosoNo ratings yet

- M1113 & M1114 Parts PDFDocument1,052 pagesM1113 & M1114 Parts PDFBogdan ZubetsNo ratings yet

- Mercedes Rescue ManualDocument117 pagesMercedes Rescue ManualReuben Lanfranco100% (2)

- 3-Gaikindo Wholesales Data Janapr2021Document3 pages3-Gaikindo Wholesales Data Janapr2021segachipNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism Checker X Originality: Similarity Found: 10%Document31 pagesPlagiarism Checker X Originality: Similarity Found: 10%khayyumNo ratings yet

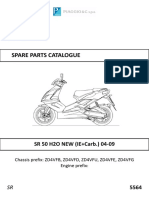

- SR 50 H2O NEW (IE+Carb.) 04-09 5564 Parts CatalogueDocument99 pagesSR 50 H2O NEW (IE+Carb.) 04-09 5564 Parts CatalogueMaciej KozłowskiNo ratings yet

- Abs Light On Dtcs c0265 c0201 U1041 Set and or Loss of Communication With Brake Module Reground Ebcm Ground 04 05 25 002d 06 14 2007Document2 pagesAbs Light On Dtcs c0265 c0201 U1041 Set and or Loss of Communication With Brake Module Reground Ebcm Ground 04 05 25 002d 06 14 2007Mrzippy TwokNo ratings yet

- 2013 CATALOG - WebDocument20 pages2013 CATALOG - WebDevin ZhangNo ratings yet