Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Session 3 - Challenge & Recognition and Enforcement

Uploaded by

AAUMCLOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Session 3 - Challenge & Recognition and Enforcement

Uploaded by

AAUMCLCopyright:

Available Formats

May 25, 2013

Session 3

After the Issuance of the Award:

- Challenge

- Recognition and Enforcement of the

Award

- Pros and Cons of Ratifying the New York

Convention

Maria L. Rubert

Solomon Ebere

Leyou Tameru

Addis Ababa, June 18, 2013

1

Outline

I. Introduction

II. Challenge to the award

III. Recognition and Enforcement of the award

IV. Pros & Cons of Ethiopia ratifying the 1958 New York

Convention

2

I. Introduction

This presentation examines the situation following the rendering of an

award: 2 possibilities

In a majority of cases, the rendering of an award is promptly

followed either by voluntary payment or by a negotiation

process between winner and loser.

In a minority of cases, the loser will resist payment

1

st

opportunity for the losing party to resist payment: by challenging

the award

2

nd

opportunity for the losing party to resist payment: by resisting

enforcement & recognition of the award

However, easier to enforce an award than a foreign court judgment

This is due in large part to the 1958 New York Convention, to which

Ethiopia is not (yet) party

3

II. Challenge to the Award

a. Effect of a successful challenge

The clock goes back to before the arbitration began

b. Types of challenges (2)

Action to set aside / Annulment

Appeal

Both are recognized under Ethiopian law

c. Grounds for challenge

Under the general international practice

Under Ethiopian law

4

II. Challenge to the Award

a. Effect of a successful challenge

The clock goes back to before the arbitration began

Awards are final and/or binding: Many arbitration agreements

and most arbitration rules stipulate that the arbitral awards that result

from arbitration under those agreements or rules are final and/or

binding

However, always possibility for a party to challenge the award

A successful challenge will usually result in the award being set

aside, vacated, or annulled, and therefore cease to exist, at least

within the jurisdiction of the court setting it aside

5

II. Challenge to the Award

b. Types of challenges (2)

Actions to set aside Appeal

By far the most important type of

challenge of an arbitral award

A dissatisfied party may challenge the

award only on limited grounds that

preclude a review of the merits, and only

in the courts of the place of arbitration

Designed to ensure that a state, through

its courts, exercises a minimum level of

control over the procedural and

jurisdictional integrity of international

arbitration taking place on its territory

Requirements (2):

Time limit within which the action must

be brought

Court in which action should be filed

Party may appeal the award before the

court on the merits.

This type of challenge is highly criticized

by the arbitration community: this type

of challenge has no place in a modern

transnational environment where the

parties objective in agreeing to

arbitration is to get away from the courts

of whatever country and entrust the

resolution of their disputes, especially of

the merits of their disputes to

international arbitrators.

Type of challenge exists only in countries

with tradition of court interference in

arbitration

6

II. Challenge to the Award

c. Grounds for challenge under general international practice (6)

Public policy (further discussed in the next slide)

Subject matter was not arbitrable

Invalid constitution of the arbitral tribunal

The award was beyond the scope of the arbitration agreement

A failure to notify an arbitrator appointment of ignition of

proceedings

The incapacity of a party or invalidity of the arbitration

agreement

7

II. Challenge to the Award

c. Grounds for challenge under general international practice (contd)

Public policy

Most troublesome of the six grounds: no accepted definition

Concept interpreted very differently by courts around the world

Some courts construe the public policy of their jurisdiction so broadly

that it becomes virtually indistinguishable from the laws of that

jurisdiction, so that any conflict of the award with the law of the place of

arbitration will lead the court to set the award aside

Broad view of public policy is prevalent in countries with tradition of

court interference in arbitration

By contrast, courts of countries with developed arbitration laws and

practice will construe public policy more narrowly, deeming it to mean

international public policy = a states most basic notions of morality

and justice

8

II. Challenge to the Award

c. Grounds for challenge under Ethiopian Law:

Action to set aside: Art. 356 CPC

Award was made according on a matter which was NOT

submitted for arbitration

Award was made on an application which time had lapsed or is

invalid

Where there were two or more arbitrators, they did not act

together

The arbitrator delegated a part of her authority to a co-

arbitrator/one of the parties/ a stranger

May 25, 2013

II. Challenge to the Award

c. Grounds for challenge under Ethiopian Law:

Appeal: Art. 351 CPC

the award is inconsistent, uncertain or ambiguous or is on its face wrong in

matter of law or fact

the arbitrator omitted to decide matters referred to her

irregularities have occurred in the proceedings:

failed to inform the parties or one of them of the time or place of the

hearing or to comply with the terms of the submission regarding

admissibility of evidence

refused to bear the evidence of material witness or took evidence in the

absence of the parties or of one of them

the arbitrator bas been guilty of misconduct:

She heard one of the parties and not the other

She was unduly influenced by one party, whether by bribes or otherwise

She acquired an interest in the subject-matter of dispute referred to her

9

10

III. Recognition & Enforcement

a. Situations where there is no need to enforce

b. Common practice to negotiate a settlement to avoid enforcement

c. Recognition v. Enforcement

d. Overview of the 1958 New York Convention (NYC)

e. Requirements to be fulfilled by petitioner

Under the NYC

Under Ethiopian Law

f. Grounds for refusal

Under the NYC

Under Ethiopian Law

11

III. Recognition & Enforcement

a. Situations where there is no need to enforce (2)

Voluntary enforcement

Over 90% of International Chamber of Commerce Arbitration Court

awards are voluntarily complied with. USAID Analysis of the Effect of Tajikistans Future Ratification of

the New York Convention, July 2007.

From 1976- 1988, courts voluntarily enforced foreign arbitral awards in

approximately 90% of arbitral awards issued under the New York

Convention. Eds. Christopher R. Drahozal, Richard W. Naimark, Towards a Science of International Arbitration, Collected

Empirical Research, 263, 2005.

Tribunal Dismisses Claims

If a party is the respondent in the arbitration and the tribunal dismisses

all claims (but does not award it costs), there is nothing to enforce

12

III. Recognition & Enforcement

b. Common practice to negotiate a settlement to avoid enforcement

A negotiation between the disputing parties will turn on time,

cost, predictability of enforcement measures, as well as the

financial ability of the debtor to satisfy the amount awarded.

Steps that can be taken to bring an award debtor to the table

Seize assets

Threaten to seize assets

Settlement discounts

Not uncommon

Allows the creditor to collect at least a portion of the amount

awarded and to avoid the cost, effort, and uncertainty of enforcement

proceedings.

13

III. Recognition & Enforcement

The offensive sword of enforcement

The defensive shield of recognition

14

III. Recognition & Enforcement

c. Recognition v. Enforcement of Awards

If the award debtor does not voluntarily comply with the award, the

creditor will need to take out enforcement proceedings in the

relevant courts if it wishes to secure the remedies afterward.

Recognition (defensive action)

Allows the applicant party to rely on the binding force of the award

in the jurisdiction at issue, and thereby to defend against actions

over the claims resolved in the award in the jurisdiction at issue.

Enforcement (offensive action)

Allows the applicant to go one step further than recognition and

seek an affirmative remedy in the enforcement jurisdiction (such as

the payment of a monetary sum)

15

III. Recognition & Enforcement

d. Overview of the 1958 New York Convention (NYC)

Primary international convention on international arbitration

Rendered awards easier to enforce than court judgments: no

worldwide treaty on recognition & enforcement of court judgments

No review on the merits

Standardized and simplified regime

Nearly universal application of the NYC: 149 signatories, including most

African states

The engine of international arbitration

Innovations

Shift of the Burden of Proof from party seeking enforcement (the

winning party) to party against whom is sought (the losing party)

Elimination of the Double Exequatur requirement

16

III. Recognition & Enforcement

d. Overview of the 1958 New York Convention (NYC) (contd)

Scope: applies to all foreign awards

Sole Criterion: place of enforcement and sometimes place of

arbitration if enforcement country has made reciprocity reservation.

Nationality of the parties is irrelevant.

Thus, the NYC is very relevant to Ethiopian parties, although Ethiopia is

not party to it, because Ethiopian parties trying to enforce award in a

state party to the NYC will benefit from the NYC regime.

NYC & National Law

Some countries implement the NYC by reference

In others, the NYC is directly applicable (e.g., Switzerland)

Where the national law is more favorable to enforcement of award

than the NYC (e.g., France), the more favorable law prevails, according to

art. VII NYC.

17

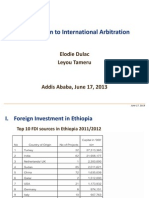

Signatories to the New York Convention

(149, as of June 2013)

18

III. Recognition & Enforcement

e. Requirements to be fulfilled by petitioner

Under the NYC: Article IV

1. To obtain the recognition and enforcement mentioned in the

preceding article, the party applying for recognition and enforcement

shall, at the time of the application, supply:

(a) The duly authenticated original award or a duly certified copy thereof;

(b) The original agreement referred to in article II or a duly certified copy

thereof.

2. If the said award or agreement is not made in an official language of

the country in which the award is relied upon, the party applying for

recognition and enforcement of the award shall produce a translation of

these documents into such language. The translation shall be certified by

an official or sworn translator or by a diplomatic or consular agent.

19

III. Recognition & Enforcement

e. Requirements to be fulfilled by petitioner

According to article 457 of CPC when an application of a

foreign award is sought, the petitioner shall:

Present a written petition

Present a certified copy of the award

Present a certificate signed proving that the award is

final and enforceable

20

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal

Under the NYC: Article V

1. Recognition and enforcement of the award may be refused, at the request of the party against

whom it is invoked, only if that party furnishes to the competent authority where the recognition and

enforcement is sought, proof that:

(a) The parties to the agreement referred to in article II were, under the law applicable to them, under

some incapacity, or the said agreement is not valid under the law to which the parties have subjected it

or, failing any indication thereon, under the law of the country where the award was made; or

(b) The party against whom the award is invoked was not given proper notice of the appointment of the

arbitrator or of the arbitration proceedings or was otherwise unable to present his case; or

(c) The award deals with a difference not contemplated by or not falling within the terms of the

submission to arbitration, or it contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to

arbitration, provided that, if the decision matters submitted to the arbitration can be separated from

those not so submitted, that part of the award which contains decisions on matters submitted to

arbitration may be recognized and enforced; or

(d) The composition of the arbitral authority or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the

agreement of the parties, or, failing such agreement, was not in accordance with the law of the country

where the arbitration took place; or

(e) The award has not yet become binding on the parties, or has been set aside or suspended by a

competent authority of the country in which, or under the law of which, that award was made.

21

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal

Under the NYC: Article V

2. Recognition and enforcement of an arbitral award may also be refused if the competent authority in

the country where recognition and enforcement is sought finds that:

(a) The subject matter of the difference is not capable of settlement by arbitration under the law of that

country; or

(b) The recognition or enforcement of the award would be contrary to the public policy of that country.

22

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

7 Grounds: First five grounds under Art. V(1) must be raised and proved

by the applicant; last two under Art. V(2) may be raised by the court on

its own motion

No review on the merits: the court cannot substitute its decision on

the merits for the decision of the arbitral tribunal, even if the arbitral

tribunal has made an erroneous decision of fact or law.

Court discretion in refusing to enforce (may must): a court may

enforce an award even if one of the seven grounds for refusing

enforcement is satisfied.

Exhaustive grounds for refusal: only grounds on which R may rely

Narrow interpretation of the grounds for refusal: restrictive approach

23

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 1: Incapacity of Party and Invalidity of Arbitration Agreement

Incapacity of a Party:

mental or physical incapacity;

lack of authority to act in the name of a corporate entity or a contracting

party being too young to sign;

lacking the power to contract

Invalidity of Arbitration Agreement:

not in writing;

no agreement to arbitrate at all within the meaning of the NYC;

illegality, duress, or fraud in the inducement of the agreement

oDallah case

24

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 2: Lack of Proper Notice, Due Process Violations, Fair Hearing

Lack of Proper Notice:

A proper notice should be in writing, contain the names of the arbitrators

and the identity of the defendant.

Parties may be notified in accordance with contractual provisions

No specific time limits for notice

Inability to present ones case:

Party must have opportunity to reply to allegations/evidence other side

No need not consider all evidence a Party wishes to Present

Language of the proceedings need not be that of the Parties

Party must have been prejudiced by lack of opportunity to present case

Active participation in the arbitration waives Due Process Objection

25

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 3: Outside or beyond the scope of the arbitration agreement

Under this defense, the applicant argues that the award is about issues

not covered by the arbitration agreement.

Drafting of the arbitration agreement is key: should give the arbitral

tribunal very broad jurisdiction to determine all disputes arising out of or

in connection with the parties substantive agreement.

Use Model Clauses published by arbitral institutions

In practice, this defense typically fails because the enforcing courts do

not want to second-guess arbitral tribunals determinations of their own

jurisdictions.

26

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 4: Irregularities in the composition of the arbitral tribunal or

the arbitration procedure

Composition of the arbitral tribunal: where a party is deprived of its

right to appoint an arbitrator or to have its case decided by an arbitral

tribunal whose composition reflects the parties agreement. Not every

deviation from agreed-upon procedure leads to refusal.

The arbitral procedure: fundamental deviations from the agreed-upon

procedure

Examples: the parties agreed to use the rules of one institution but the

arbitration is conducted under the rules of another, or even where the

parties have agreed that no institutional rules would apply.

27

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 5: Award not binding, set aside, or suspended

Award is not yet binding on the parties:

What does binding mean? Courts differ. Some courts consider that

this moment is to be determined under the law of the country where the

award was made. Other courts hold that an award is binding when

ordinary means of recourse are no longer available against them.

Award has been set aside or suspended:

the country in which the award was made: the place of arbitration

Under the law of which the award was made: the applicable

arbitration law.

The effect of an annulled Award on its enforcement varies from

country to country

28

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 6: not arbitrable (i.e., where the dispute involves a subject

matter reserved for the courts)

Whether a subject matter of an arbitration is non-arbitrable is a

question to be determined under the law of the country where the

application for recognition and enforcement is being made

Ground to be raised by the court. However, typically raised by the party

resisting recognition /enforcement when believed to be relevant

Non-arbitrable matters: divorce, custody, property settlements, wills,

bankruptcy, winding up of companies

oBG Group v. Argentina (D.C. Cir, 2002)

29

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal (contd)

Ground 7: contrary to public policy

No definition of public policy: depends on enforcing State

Pro-arbitration countries: narrow interpretation of public policy, thus

courts rarely refuse enforcement on this ground

Non-friendly arbitration countries: broader interpretation, thus courts

more frequently refuse enforcement on public policy grounds

Distinction: domestic v. international public policy

International public policy: (i) fundamental principles pertaining to

justice or morality; (ii) rules designed to serve the essential political,

social or economic interests of the State (public policy rules or lois de

police); (iii) the duty of the State to respect its obligations towards other

States or international organizations (ILA Recommendations)

30

III. Recognition & Enforcement

f. Grounds for refusal

Under Ethiopian Law: Art. 461 CPC

Reciprocity

Regular arbitration agreement

Parties had equal rights in appointing arbitrators

Arbitration tribunal was regularly constituted

Arbitrability of subject matter

Enforceability of award

Award not contrary to public order or morals

May 25, 2013

III. Recognition & Enforcement

Grounds for refusal under Ethiopian Law

The issue of

RECIPROCITY (Art. 458(a) CPC)

How is reciprocity established in court?

Treaty of Judicial assistance

Paulos Papassinous case

Goh-Tsibah Menkreselassie vs Dr. Bereket Habetselassie

ARBITRABILITY

What is arbitrable under Ethiopian law? CC 3326(2)

Water Resource Ministry v. Siyoum & Ambaye General

Contractors

31

32

IV. Pros & Cons of Ethiopia Ratifying the NYC

a. Pros

Improving the Business Environment

Non-Contracting States are at a competitive disadvantage: a foreign investor

may decide not to invest in a non-NYC country, or if it does, it will negotiate

contractual terms to compensate for the increased risk, i.e., less advantageous

for its contracting party.

Prior to Ratification, Brazil was seen as the black sheep of Latin America in its

approach to arbitration and foreign investors voiced concern about lack of

protection for their investments. Leonardo Daldegan Lima, The Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards

in Brazil before and after the Ratification of the New York Convention, Section A.2., Young ICCA Blog 2013 (quoting Nigel

Blackaby, Arbitration and Brazil: A Foreign Perspective, Arbitration International, vol. 17, n. 2 (London: LCIA, 2001)).

Ratification is estimated to benefit the economy of Tajikistan by $155 million

per year. USAID Analysis of the Effect of Tajikistans Future Ratification of the New York Convention, 11, 2007.

Welcoming large-scale investments

33

IV. Pros & Cons of Ethiopia Ratifying the NYC

a. Pros (contd)

Complementing the National Courts

Promotion of International Arbitration is conducive to an improved

administration of justice in that it eases courts caseloads and enables them to

better address non-commercial disputes

Integration in the Global Legal Community

Legal Practitioners in non-Contracting States are less likely to be nominated as

arbitrators and the parties choice of seat is less likely to be in a non-Contracting

State

In 1997, while less than 60% of parties to ICC arbitrations were from Western

Europe/North America, more than 85% of arbitrators nominated were domiciled

in Western Europe/North America

In nearly 90% of the above cases, the seat of the arbitration was also in

Western Europe/North America. Enforcing Arbitration Awards under the New York Convention, 9, 19

Paper from New York Convention Day, 1998.

34

IV. Pros & Cons of Ethiopia Ratifying the NYC

b. Cons

No additional benefit to ratification?

Investors, Counsel, and Arbitrators from Contracting States are hesitant to

transact with Non-Contracting States and related entities/individuals, due to

higher risk of being subject to idiosyncratic national courts at the

recognition/enforcement stage

Ethiopia may benefit from a number of small-scale foreign investments, but

large-scale investments depend on an efficient and reliable International

Arbitration mechanism

Potential Conflicts between New York Convention and Domestic Law?

Ethiopia codified domestic arbitration law in the Civil Code of 1965 and the

Civil Code of Procedure of 1965; the New York Convention does not conflict,

but rather encourages the clarification and further development of domestic

law

35

IV. Pros & Cons of Ethiopia Ratifying the NYC

c. Case Studies

UAE: the Road ahead after the Accession to the NYC

Member since 2006: Why?

Initial Applications:

International Bechtel v. Department of Civil Aviation of the

Government of Dubai, Dubai Court of Cassation, petition No.

503/2003, judgment dated 15 May 2005 Annulment; ED: WASNT

IT A SET ASIDE, NOT NYC, DECISION?

Pros-Cons: UAE- US/France.

Latest Applications:

Fujairah Federal Court of First Instance No. 35/2010: court

recognized and ratified foreign arbitral awards issued in London.

Dubai Appeal Court in Civil Case No. 531/2011: court recognized

and enforced an award issued in Singapore.

Maxtel International FZE v. Airmec Dubai LLC (Court of First

Instance Commercial Action No. 268/2010, dated 12 January 2011)

36

IV. Pros & Cons of Ethiopia Ratifying the NYC

Final Thoughts

This landmark instrument has many virtues. It has nourished respect for binding

commitmentsIt has inspired confidence in the rule of law. And it has helped ensure

fair treatment when disputes arise over contractual

rights and obligations.

. . . Still, a number of States are yet to become parties

to the Convention. As a result, entities investing or

doing business in those States lack legal certainty

afforded by the Convention, and businesses cannot be confident that commercial

obligations can be enforced. This increases the level of risk, meaning that additional

security may be required, that negotiations are likely to be more complex and protracted,

and that transaction costs will rise.

Such risks can adversely affect international trade. Kofi Annan, Secretary General of the UN, 1998.

Contact Information

Solomon Ebere

Schellenberg Wittmer

15 bis, rue des Alpes

P.O. Box 2088

1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland

Tel: +41227078000

Solomon.Ebere@swlegal.ch

Maria L. Rubert

Cramer-Salamian LLP

PO Box 186549

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Tel: +971 4 227 74 27

Email:rubert@cramer-salamian.com

Leyou Tameru

Legal consultant

Tel: +251911737251

Leyou.tameru@gmail.com

You might also like

- Foreign Award ChallengesDocument16 pagesForeign Award ChallengesVivek SaiNo ratings yet

- ADR Report Flowchart and OutlineDocument11 pagesADR Report Flowchart and OutlineJay-ar Orallo100% (1)

- ADR Reviewer MidtermDocument7 pagesADR Reviewer MidtermTom SumawayNo ratings yet

- Special Civil Actions Memo AidDocument9 pagesSpecial Civil Actions Memo Aidgeorge_alsoNo ratings yet

- Lamar Jost Civpro IIDocument81 pagesLamar Jost Civpro IIdsljrichNo ratings yet

- Annulment Proccess of A An ICSID AwardDocument55 pagesAnnulment Proccess of A An ICSID AwardIonutStoichitaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 - Remedies and Expert EvidenceDocument61 pagesLecture 9 - Remedies and Expert EvidenceAlonzo McwonaNo ratings yet

- SG 4.2 Interim Payments, Security For Costs, Sanctions, DiscontinuanceDocument10 pagesSG 4.2 Interim Payments, Security For Costs, Sanctions, DiscontinuanceFarid Faisal ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Private International LawDocument12 pagesPrivate International LawSHRUTI SINGHNo ratings yet

- 1.what Is Arbitra Tion?: RA 876. Arbitration LawDocument4 pages1.what Is Arbitra Tion?: RA 876. Arbitration LawEks WaiNo ratings yet

- Advantages of arbitration over litigationDocument3 pagesAdvantages of arbitration over litigationivy_pantaleonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Redfern NotesDocument6 pagesChapter 11 Redfern NotesAnnadeJesusNo ratings yet

- Primer On Injunctions and TroDocument10 pagesPrimer On Injunctions and Tro83jjmackNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Vs Brown Smith Doc 3Document16 pagesLawsuit Vs Brown Smith Doc 3Time Warner Cable NewsNo ratings yet

- Case Summary: International CommerceDocument4 pagesCase Summary: International CommerceSoohyun ImNo ratings yet

- Challenging an Arbitration AwardDocument22 pagesChallenging an Arbitration AwardPS PngnbnNo ratings yet

- Attempts To Set Aside An Award: Chapter NineDocument9 pagesAttempts To Set Aside An Award: Chapter NineDhwajaNo ratings yet

- Interim ReliefDocument16 pagesInterim ReliefMariel David100% (1)

- Challenging An Arbitration AwardDocument22 pagesChallenging An Arbitration AwardPS PngnbnNo ratings yet

- Arbitration ActDocument3 pagesArbitration ActSanjay MitalNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Common Civil Justice Processes - Edit 20210305Document28 pagesA Guide To Common Civil Justice Processes - Edit 20210305Dave YangNo ratings yet

- En 4 Pers Arbitration As A Final Award Challenges and EnforcementDocument27 pagesEn 4 Pers Arbitration As A Final Award Challenges and EnforcementAndreea DydyNo ratings yet

- Civil-Procedure B 2022Document62 pagesCivil-Procedure B 2022portiadavies676No ratings yet

- Updated 2023 Civil Procedure B NotesDocument72 pagesUpdated 2023 Civil Procedure B NotesChiedza Caroline ChikwehwaNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Black Letter OutlineDocument23 pagesCiv Pro Black Letter OutlineGaye BlackmanNo ratings yet

- AdjudicationDocument5 pagesAdjudicationTanver ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Enforcing Construction Dispute Arbitration AwardsDocument7 pagesEnforcing Construction Dispute Arbitration AwardsZinck HansenNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure NotesDocument24 pagesCivil Procedure Notes钟良耿No ratings yet

- Specpro Finals ReviewerDocument148 pagesSpecpro Finals ReviewerAlex Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Legal and Equitable Remedies OutlineDocument14 pagesLegal and Equitable Remedies OutlineLindsey HornNo ratings yet

- Pilot Expedited Civil Litigation RulesDocument14 pagesPilot Expedited Civil Litigation RulesAlfred DanezNo ratings yet

- EMMASDocument25 pagesEMMASMuhaye BridgetNo ratings yet

- Role of Courts in Early ArbitrationDocument2 pagesRole of Courts in Early ArbitrationCarlo PajoNo ratings yet

- Civil Pro (Ed)Document17 pagesCivil Pro (Ed)JoseLuisBunaganGuatelaraNo ratings yet

- Ra 876Document5 pagesRa 876Dandy CruzNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Reports For MidtermDocument29 pagesConsolidated Reports For MidtermAileen BaldecasaNo ratings yet

- Alternative Disputes ResolutionDocument6 pagesAlternative Disputes ResolutionVAT CLIENTSNo ratings yet

- Principles of Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign AwardDocument6 pagesPrinciples of Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign AwardJay-r TumamakNo ratings yet

- Arbitration AbridgedDocument5 pagesArbitration AbridgedMaggie Wa MaguNo ratings yet

- CivPro Rule 5 Small ClaimsDocument38 pagesCivPro Rule 5 Small ClaimsARTSY & CRAFTIESNo ratings yet

- Small ClaimsDocument6 pagesSmall ClaimsWhere Did Macky GallegoNo ratings yet

- The Alternative Dispute Resolution and The Arbitration Law-MergedDocument157 pagesThe Alternative Dispute Resolution and The Arbitration Law-MergedGrace Managuelod GabuyoNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document13 pagesUnit 3Aman GuptaNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro OutlineDocument52 pagesCiv Pro Outlinestacy.zaleskiNo ratings yet

- Intro To Civil ProcedureDocument5 pagesIntro To Civil Procedureliam mcphearsonNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Outline - Semester 1Document49 pagesCivil Procedure Outline - Semester 1Lauren C WalkerNo ratings yet

- ADR ReportDocument5 pagesADR ReportRochi Maniego Del MonteNo ratings yet

- Recognition and Enforcement or Setting Aside of An International Commercial Arbitration AwardDocument34 pagesRecognition and Enforcement or Setting Aside of An International Commercial Arbitration Awardsherwinjan.navarroNo ratings yet

- International Commercial ArbitrationDocument20 pagesInternational Commercial ArbitrationMd. Iftekhar Alam AsifNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document19 pagesChapter 1Akshat JainNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1 - Overview and Pre-Commencement ConsiderationsDocument7 pagesSeminar 1 - Overview and Pre-Commencement ConsiderationsJonathan TaiNo ratings yet

- Finra Ruling in Larry Hagman's Case Against CitigroupDocument7 pagesFinra Ruling in Larry Hagman's Case Against CitigroupDealBookNo ratings yet

- Introduction To International Trade Law Note 3 of 13 Notes: Dispute SettlementDocument40 pagesIntroduction To International Trade Law Note 3 of 13 Notes: Dispute SettlementMusbri MohamedNo ratings yet

- ADR Resci NotesDocument40 pagesADR Resci NotesJose Gerfel GeraldeNo ratings yet

- Special Civil ActionsDocument17 pagesSpecial Civil ActionsWhere Did Macky Gallego100% (1)

- Small Claims & Summary ProcedureDocument15 pagesSmall Claims & Summary Procedureshamymy100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitDocument21 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civil Pro Combined NotesDocument212 pagesCivil Pro Combined NotesMiles HuiNo ratings yet

- Iran-United States Claims Arbitration: Debates on Commercial and Public International LawFrom EverandIran-United States Claims Arbitration: Debates on Commercial and Public International LawNo ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413From EverandPetition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413No ratings yet

- Drafting International Arbitration AgreementsDocument44 pagesDrafting International Arbitration AgreementsAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Session 2 - Arbitration ProceedingsDocument42 pagesSession 2 - Arbitration ProceedingsAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Session 1 - Introduction To IADocument17 pagesSession 1 - Introduction To IAAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Imm5645e PDFDocument0 pagesImm5645e PDFkulwinderpuriNo ratings yet

- 33Document8 pages33AAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Coca Cola Case Study AnalysisDocument18 pagesCoca Cola Case Study AnalysisAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Management Science FinalDocument8 pagesManagement Science FinalAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Promotion of Foreign ExchangeDocument26 pagesPromotion of Foreign ExchangeAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- 33Document8 pages33AAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Tax On Partially Produced Skin For ExportDocument2 pagesTax On Partially Produced Skin For ExportAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Tax On Coffee ExchangeDocument2 pagesTax On Coffee ExchangeAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- Accelerated Refund of Taxes Paid of Foreign Exchange PDFDocument4 pagesAccelerated Refund of Taxes Paid of Foreign Exchange PDFYoftahe.MNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The Financial System and The Role of Financial InstitutionsDocument15 pagesAn Overview of The Financial System and The Role of Financial InstitutionsAAUMCLNo ratings yet

- GR No. L 12219Document5 pagesGR No. L 12219Ken AggabaoNo ratings yet

- Ormoc Sugar Planters Association, Inc., Et Al.v. CA G.R. No. 156660Document9 pagesOrmoc Sugar Planters Association, Inc., Et Al.v. CA G.R. No. 156660jeesup9No ratings yet

- Bar Bri Outline IIIDocument153 pagesBar Bri Outline IIIrgvcrazy09100% (1)

- Quimiguing v. Icao (G.R. No. L-26795 July 31, 1970)Document3 pagesQuimiguing v. Icao (G.R. No. L-26795 July 31, 1970)Hershey Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Joseph Thomas vs. Duke University: Lawsuit Update 4.28.17Document3 pagesJoseph Thomas vs. Duke University: Lawsuit Update 4.28.17thedukechronicleNo ratings yet

- Joint Stipulation Regarding Briefing Schedule For Plaintiff's Motion To Dismiss Voluntarily and Continuance of Trial and Related DatesDocument7 pagesJoint Stipulation Regarding Briefing Schedule For Plaintiff's Motion To Dismiss Voluntarily and Continuance of Trial and Related DatesPolygondotcomNo ratings yet

- Cases FulltextDocument43 pagesCases FulltextRen ConchaNo ratings yet

- 14 1989 - Leo Pita and His "Pinoy Playboy" MagazinesDocument11 pages14 1989 - Leo Pita and His "Pinoy Playboy" MagazinesAnonymous VtsflLix1No ratings yet

- Dino v. Judal-LootDocument3 pagesDino v. Judal-LootAntonJohnVincentFriasNo ratings yet

- Taxation Notes on ObligationsDocument8 pagesTaxation Notes on ObligationsJB Suarez0% (1)

- Municipality of Pililla V CA DigestDocument1 pageMunicipality of Pililla V CA DigestJolet Paulo Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- 2-24-17 DOJ Motion To Hold in AbeyanceDocument6 pages2-24-17 DOJ Motion To Hold in AbeyanceZoe Tillman100% (1)

- ROLITO GO y TAMBUNTING vs. COURT OF APPEALSDocument19 pagesROLITO GO y TAMBUNTING vs. COURT OF APPEALSMarinel June PalerNo ratings yet

- Baguio Midland Courier Vs CADocument11 pagesBaguio Midland Courier Vs CAMDR LutchavezNo ratings yet

- Ra 6727 8188 Labor Law PhilippinesDocument20 pagesRa 6727 8188 Labor Law PhilippinesGeorge PandaNo ratings yet

- TAWANG v. La TrinidadDocument17 pagesTAWANG v. La TrinidadMarie Nickie BolosNo ratings yet

- Portugal Vs Portugal-Beltran - DigestDocument3 pagesPortugal Vs Portugal-Beltran - DigestRowena Gallego100% (1)

- Criminal Justice SystemDocument32 pagesCriminal Justice SystemKim Jan Navata Batecan100% (1)

- Court upholds counsel's admissions binding clientDocument6 pagesCourt upholds counsel's admissions binding clientjomalaw6714No ratings yet

- Case Digest ConstiDocument58 pagesCase Digest ConstiAtlas LawOfficeNo ratings yet

- Sullivan v. O'ConnorDocument2 pagesSullivan v. O'ConnorcrlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- Civpro - Answer With Counterclaim and Cross-ClaimDocument7 pagesCivpro - Answer With Counterclaim and Cross-ClaimHanna Mae MataNo ratings yet

- Revision Seeks Fair Trial in Land Dispute CaseDocument13 pagesRevision Seeks Fair Trial in Land Dispute CaseSaurabh ManikpuriNo ratings yet

- Legal Opinion #1: Cinder Ella Written by Kane WelshDocument4 pagesLegal Opinion #1: Cinder Ella Written by Kane WelshMusicalityistNo ratings yet

- Balfour V Balfour NotesDocument3 pagesBalfour V Balfour NotesAliNo ratings yet

- Data Privacy CompilationDocument239 pagesData Privacy CompilationJan Oliver YaresNo ratings yet

- Contract: The Elements of A ContractDocument21 pagesContract: The Elements of A ContractsbikmmNo ratings yet

- Complaint - Sample PleadingDocument7 pagesComplaint - Sample PleadingBryan Arias100% (1)

- Rule 118: Pre - Trial: Criminal Procedure Notes (2013 - 2014) Atty. Tranquil SalvadorDocument3 pagesRule 118: Pre - Trial: Criminal Procedure Notes (2013 - 2014) Atty. Tranquil SalvadorRache GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument6 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet