Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Publication of

Uploaded by

FebniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Publication of

Uploaded by

FebniCopyright:

Available Formats

Publication of IADVL,

WB

Official organ of AADV

IJ

D

Users

online:

76

Hom

e

Editorial

Board

Current

Issue

Archive

s

Comin

g

Soon

Guideline

s

Subscriptio

ns

e-

Alerts

Login

Click here to download free Android Application for this and

other journals Click here to view optimized website for

mobile devices Journal is indexed with PubMed

Share on facebookShare on twitterShare on citeulikeShare on

googleShare on linkedinMore Sharing Services

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Year : 2012 | Volume : 57 | Issue : 6 | Page : 428-433

The Effect of Hypoallergenic Diagnostic Diet in

Adolescents and Adult Patients Suffering from

Atopic Dermatitis

Jarmila Celakovsk

1

, K Ettlerov

2

, K Ettler

1

, J Bukac

3

, M Belobrdek

1

1

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Faculty Hospital and

Medical Faculty of Charles University, Hradec Krlov, Czech Republic

2

Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Outpatient Clinic,

Hradec Krlov, Czech Republic

3

Department of Medical Biophysics, Medical Faculty of Charles University

in Hradec Krlov, Czech Republic

Date of Web

Publication

1-Nov-

2012

Correspondence Address:

Jarmila Celakovsk

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Faculty Hospital and

Medical Faculty of Charles University, Hradec Krlov

Czech Republic

Search

GO

Similar in PUBMED

Search Pubmed

for

Celakovsk J

Ettlerov K

Ettler K

Bukac J

Belobrdek M

Search in Google

Scholar for

Celakovsk J

Ettlerov K

Ettler K

Bukac J

Belobrdek M

Related articles

Atopic dermatitis

diagnostic

hypoallergenic

diet

SCORAD system

Article in PDF (593

KB)

Citation Manager

Access Statistics

Reader Comments

Email Alert *

Add to My List *

* Registration required

(free)

DOI: 10.4103/0019-5154.103065

PMID: 23248359

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the effect of a diagnostic hypoallergenic diet

on the severity of atopic dermatitis in patients over 14 years of

age. Materials and Methods: The diagnostic hypoallergenic

diet was recommended to patients suffering from atopic

dermatitis for a period of 3 weeks. The severity of atopic

dermatitis was evaluated at the beginning and at the end of

this diet (SCORAD I, SCORAD II) and the difference in the

SCORAD over this period was statistically

evaluated. Results: One hundred and forty-nine patients

suffering from atopic dermatitis were included in the study:

108 women and 41 men. The average age of the subjects was

26.03 (SD: 9.6 years), with the ages ranging from a minimum

of 14 years to a maximum of 63 years. The mean SCORAD at

the beginning of the study (SCORAD I) was 32.9 points (SD:

14.1) and the mean SCORAD at the end of the diet (SCORAD

II) was 25.2 points (SD: 9.99). The difference between

SCORAD I and SCORAD II was evaluated with the Wilcoxon

signed-rank test. The average decrease of SCORAD was 7.7

points, which was statistically significant

(P=.00000). Conclusion: Introduction of the diagnostic

hypoallergenic diet may serve as a temporary medical

solution" in patients suffering from moderate or severe forms

of atopic dermatitis. It is recommended that this diet be used

in the diagnostic workup of food allergy.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, diagnostic hypoallergenic diet,

SCORAD system

How to cite this article:

Celakovsk J, Ettlerov K, Ettler K, Bukac J, Belobrdek M. The

Effect of Hypoallergenic Diagnostic Diet in Adolescents and Adult

Patients Suffering from Atopic Dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol

2012;57:428-33

Abstract

Introduction

The Aim

Materials and Me...

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

Article Figures

Article Tables

Article Access

Statistics

Viewed 661

Printed 14

Emailed 1

PDF

Downloaded

48

Comments [Add]

Cited by

others

2

Gadgets powered

by Google

How to cite this URL:

Celakovsk J, Ettlerov K, Ettler K, Bukac J, Belobrdek M. The

Effect of Hypoallergenic Diagnostic Diet in Adolescents and Adult

Patients Suffering from Atopic Dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol [serial

online] 2012 [cited 2014 May 22];57:428-33. Available

from: http://www.e-ijd.org/text.asp?2012/57/6/428/103065

What was known? The role of food allergy remains controversial in older

children and adult patients suffering from atopic dermatitis, few studies

concerning the food allergy in this group of patients are available.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, intermittent, inflammatory,

genetically predisposed skin disease that is characterized by

severe pruritus and xerosis. A number of environmental

factors have been implicated in its pathogenesis.

The role of food allergy in atopic dermatitis has been a subject

of controversy in dermatology, but today there is definite

evidence that food allergy has a role in the pathogenesis of the

disease. The importance of food allergy in children with atopic

dermatitis has been confirmed by extensive studies,

[1]

but the

role of food allergy remains controversial in older children and

in adults suffering from this disease.

Many food reactions in people with atopic dermatitis may not

necessarily be mediated through immune reactions.

[2]

As

sensitization to food early in life may be a predisposing

factor,

[3]

it is important to investigate whether the elimination

of dietary triggers can help alleviate the symptoms of atopic

dermatitis. The role of dietary factors in atopic dermatitis-

either as a causative factor or as a treatment measure through

the use of exclusion diets- remains unclear.

[4]

Many

researchers advocate double-blind placebo-controlled food

challenges to establish whether a child has a true food

allergy.

[5]

There is a vast amount of literature claiming that dietary

elimination of specific foodstuffs causes improvement of atopic

dermatitis in some cases. However, much of the evidence fails

to withstand close scrutiny.

[2]

The advantage of dietary

interventions is that they may address one of the primary

causes, as opposed to treatments that merely suppress the

symptoms. However, there can be serious consequences to

any dietary manipulation that leaves the individual deficient in

calories, protein, or minerals such as calcium.

[6],[7]

Avoidance

of multiple foods is potentially hazardous and requires

continuing dietary supervision in the pediatric age-group.

[6]

According to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical

Immunology (EAACI) position paper, in case of suspected food

allergy (by history and/or specific sensitization), a diagnostic

elimination diet is recommended over a period of up to 4-6

weeks, with the exclusion of the suspected food items. If the

role of food in persistent moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

is unclear, the patient should maintain a daily record of

symptoms (including the status of atopic dermatitis, intensity

of itch, and sleep loss) and the intake of specific foods. These

protocols will give an overview of the patient's diet and may

point to a possible relation between the worsening of eczema

and specific food intake. If there is no such association and the

diagnostic procedures outlined above do not provide helpful

information, the introduction of a diagnostic hypoallergenic

diet over a period of at least 3 weeks can be helpful in severe

atopic dermatitis.

[8]

If the condition of atopic dermatitis

remains stable or increases within 4 weeks during the

diagnostic elimination diet, it is unlikely that food allergy is a

relevant trigger factor for the atopic dermatitis, and open food

challenges are then not necessary. It has to be taken into

account that in rare cases a food that was 'allowed' during the

elimination diet may be responsible for persistent symptoms.

The European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD) has

developed the SCORAD (SCORing AD) index to create a

consensus on assessment methods for atopic dermatitis so

that the results of different trials can be compared.

[9]

The Aim

The aim of our study was to evaluate, using the SCORAD

system, the effect of a diagnostic hypoallergenic diet taken for

a period of at least 3 weeks. This diet was recommended to

patients suffering from atopic dermatitis in the diagnostic

workup of food allergy before open exposure tests with

suspected food allergens.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients over 14 years of age with atopic dermatitis who were

examined at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology,

Faculty Hospital and Medical Faculty of Charles University,

Hradec Krlov, Czech Republic, from January 2005 to April

2008 were included in the study. The diagnosis of atopic

dermatitis was made according to the the Hanifin-Rajka

criteria.

[10]

All patients signed informed consent forms prior to inclusion in

the study, and the permission of the local ethics committee

was obtained for conducting this study.

Examinations

Complete dermatological and allergological examination was

performed in all included patients at the allergological

outpatient department, with evaluation of the occurrence of

bronchial asthma and of the occurrence of perenial or seasonal

rhinoconjunctivities.

Personal history

A detailed personal history of possible food allergy was taken

in all included patients. The patients were asked if they

suffered from immediate or late food adverse reactions

affecting the skin (itching, rush, urticaria, worsening of atopic

dermatitis), gastrointestinal tract, or respiratory tract. History

of food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA),

occupational asthma and rhinitis, and contact urticaria was

also elicited.

Examinations

The diagnostic workup of food allergy (including skin prick

tests, atopy patch tests, and measurement of specific serum

IgE) to wheat, cow's milk, peanut, soy, and egg was

performed before the diagnostic hypoallergenic diet was

started. This was done during intervals when the patient had

mild symptoms of atopic dermatitis (as evaluated with

SCORAD).

Open exposure test and double-blind placebo-controlled food

challenge tests with suspected food allergens were performed

after the diagnostic hypoallergenic diet during intervals when

the patient had mild symptoms of atopic dermatitis.

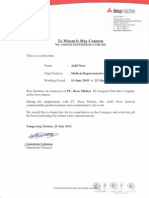

[Figure 1] shows the diagnostic algorithm for the identification

of food allergy in atopic dermatitis patients and the inclusion of

the diagnostic hypoallergenic diet in the diagnostic workup of

food allergy in patients suffering from atopic dermatitis.

[8]

Figure 1: Diagnostic algorithm for the

identification of food allergy in atopic

dermatitis

Click here to view

Scoring of atopic dermatitis

The diagnosis of atopic dermatitis was made using the Hanifin-

Rajka criteria

[10]

at the Department of Dermatology and

Venereology, Faculty Hospital and Medical Faculty of Charles

University, Hradec Krlov, Czech Republic.

Severity of eczema was scored using the SCORAD

index,

[9]

which includes assessment of topography items

(affected skin area), intensity criteria, and subjective

parameters. To measure the extent of atopic dermatitis, the

rule of nines was applied on a front/back drawing of the

patient's body. The extent can be graded on a scale of 0 to

100. The intensity part of the SCORAD index consists of six

items: Erythema, edema/papulation, excoriations,

lichenification, crusts, and dryness. Each of these items can be

graded on a scale of 0 to 3. The subjective items include daily

pruritus and sleeplessness. Both subjective items can be

graded on a 10-cm visual analog scale. The maximum

subjective score is 20. All items were entered in the SCORAD

evaluation form. The SCORAD index was calculated using the

formula: A/5 + 7B/2 + C. In this formula, A represents the

extent (0-100), B represents the intensity (0-18), and C

represents the subjective symptoms (0-20).

The severity of atopic dermatitis as evaluated with SCORAD

was graded as mild (20 points), moderate (20- 50 points), or

severe (>50 points). The severity of atopic dermatitis was

evaluated with the SCORAD system at the beginning of the

diagnostic hypoallergenic diet and at the end of this diet

(before the exposure tests).

The diagnostic hypoallergenic diet

This diet was designed to be free of any additives and

allergens and was suggested to the patient during the

diagnostic workup of food allergy; it was introduced after

obtaining the patient's informed consent.

Over the period of 3 weeks we recommended the following

foods:

Gluten-free foods

Potatoes, rice

Beef, pork, and chicken meat

Vegetable and fruits only after thermal modification;

but parsley, celery, and seasoning were not allowed

The patient was allowed to drink only plain drinking

water, mineral water, or black tea.

No other foods and drinks were allowed during this

period of 3 weeks.

During this diet the patient was allowed to treat himself with a

low-potency topical corticosteroid. Other anti-inflammatory

substances and ultraviolet (UV) therapy were not permitted.

Results

Patients

One hundred and forty-nine persons-108 women and 41 men-

entered the study. The average age was 26.03 years (SD: 9.6

years), with the minimum age being 14 years and the

maximum 63 years. The mean SCORAD was 32.9 points (SD:

14.11) (maximum 79.5 points; minimum 12.5 points) at the

beginning of the study. The mean SCORAD at the end of the

diet was 25.2 (SD: 9.99). These data and the clinical

characteristics of patients are presented in [Table 1].

Table 1: Patient older than 14 years of

age suffering from atopic dermatitis -

characteristics

Click here to view

In all patients a complete allergological examination was

performed. The data about the occurrence of bronchial

asthma, occurrence of seasonal or perennial

rhinoconjunctivitis, the onset of atopic dermatitis, and family

history of atopy were recorded [Table 1].

[Table 2] demostrates the categorization of the 149 patients

according the severity of their atopic eczma at the beginning

of the diet and at the end of the diet. At the beginning of the

diet 32 (22%) patients suffered from the mild form, 97 (65%)

from the moderate form, and 20 (13%) from the severe form

of atopic dermatitis. The mean SCORAD at the start of the

study was 32.9 (SD: 14.1). The mild form of atopic dermatitis

was recorded at the end of the diet in 50 (33%) patients, the

moderate form in 92 (62%) patients, and the severe form in 7

(5%) patients. The mean SCORAD at the end of this diet was

25.2 (SD: 9.99).

Table 2: Patients categorized according

the severity of atopic dermatitis at the

beginning of the diet and at the end of

the diet (with the mean SCORAD)

Click here to view

[Table 3] demonstrates the number of patients with increase

and decrease in SCORAD at the end of the diet. Decrease of

SCORAD was recorded in 119 patients (80%). A decrease of

SCORAD by only about 1 point was recorded in 6 of the 119

patients, while in 113 patients (76%) the decrease of SCORAD

was by more than 1 point. The mean decrease in the SCORAD

was 7.7 points.

Table 3: SCORAD at the end of the diet

Click here to view

Increase of SCORAD was recorded in three patients and in all

of them the increase was by 3 points. No changes during this

diet were recorded in another 27 patients (18%), i.e. the level

of SCORAD at the beginning of the diet and at the end of the

diet were the same.

Statistical evaluation of SCORAD

SCORAD at the beginning and at the end of diagnostic

hypoallergenic diet was evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-

rank test. We rejected the null hypothesis about the

conformity in SCORAD I and SCORAD II because the average

difference of 7.7 points was substantial and statistically

significant (P = 0.00001).

Discussion

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, intermittent, inflammatory skin

disease that may be associated in some cases with food

allergies. Numerous other trigger factors for atopic dermatitis

have been identified, including inhalable respiratory allergens,

irritative substances, and infectious microorganisms such as

Staphylococcus aureus. Psychogenic and climatic factors may

also cause exacerbations of atopic dermatitis.

The epidermal barrier plays a crucial role in protecting the

body against infection and other exogenous insults by

minimizing transepidermal water loss and by conferring

immunological protection.

[11]

Filaggrin gene defects

substantially increase the risk of atopic dermatitis. The

increased skin permeability in those with such defects may

increase the risk of sensitization to food and other allergens,

indicating the importance of cutaneous allergen avoidance in

early life to prevent the onset of atopic dermatitis and food

allergy.

[11]

Food allergy appears to be an important factor in the

exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in only a subset of children

(and a much smaller subset of adults). Non- IgE- mediated

mechanisms are sometimes implicated in the atopic dermatitis

flare-ups associated with ingestion of the foods in question,

and food allergy appears to have little or no role in children

with nonatopic dermatitis.

[12],[13],[14]

In a questionnaire survey

of schoolchildrens' perceptions regarding the factors

influencing their atopic dermatitis,

[15]

an extremely small

proportion (8%) of respondents believed that certain foods or

drinks had an effect on their eczema. A survey of adults in

High Wycombe showed that 20% perceived exacerbations of

their atopic dermatitis as adverse reactions to specific foods,

but only 1% had confirmed food allergies.

[16]

According to

Sicherer, both atopic dermatitis and food allergy are, in the

majority of individuals, transitory conditions that improve with

increasing age.

[17]

It is important to determine the severity of atopic dermatitis

for evaluation of disease improvement after and during

therapy. Scoring of the severity of atopic dermatitis is

demanded in clinical trials. The ETFAD has developed the

SCORAD index to create a consensus on assessment methods

for atopic dermatitis so that study results of different trials can

be compared.

[18]

To evaluate the effect of the diagnostic hypoallergenic diet we

calculated the SCORAD index at the beginning and at the end

of this diet in all included 149 patients. This diet was

recommended for 3 weeks and was clearly explained to the

patient at the beginning of the study.

Patients were asked to record the symptoms of atopic

dermatitis (the extent of involved skin, itching, sleep disorder,

etc.) and any other health problems in special forms. In 119

(79.8%) patients there was improvement of atopic dermatitis,

as indicated by the decrease of SCORAD. In 6 of these

patients, the decrease of SCORAD was only by 1 point, while in

113 patients (75%) the decrease of SCORAD was by more

than 1 point. The average level of the SCORAD decrease was

7.7 points. Worsening of atopic dermatitis was recorded during

this diet in three patients, with increase of SCORAD by 3

points in all three cases. No changes in the severity of atopic

dermatitis during this diet were recorded in another 27

patients, with the level of SCORAD at the beginning and at the

end of this diet being the same.

Before the beginning of the diet the majority of patients in our

study suffered from the moderate form of atopic dermatitis (97

patients), 32 from the mild form, and 20 from the severe form

of the disease. At the end of the diet, improvement was

recorded in the 20 patients with the severe form of atopic

dermatitis, with only 7 of these 20 patients continuing to have

severe disease; the SCORAD index was about 45 points in

these patients at the end of 3 weeks, indicating a moderate

form of atopic dermatitis. Although the average decrease in

SCORAD (by 7.7 points) was not very marked from the clinical

point of view, most of the patients evaluated this diet as

having a favorable effect. The majority of the patients

indicated that pruritus of the skin was diminished and that

they could sleep better.

On the basis of our results we can conclude that introduction

of the diagnostic hypoallergenic diet can serve as a temporary

medical solution in adolescents and adult patients suffering

from moderate and severe forms of atopic dermatitis.

After 3 weeks of the diagnostic hypoallergenic diet the patients

were allowed to introduce the suspected food in their meals

and educated about the performance of challenge tests with

the probable food allergen. They were informed about the

possibility of cross-allergy with pollen and about the risk

associated with consuming meals containing aromatic additives

and histaminoliberators. All patients were recommended an

additive-free diet, with a low content of biogenic

amines.Patients with chronic urticaria or atopic dermatitis may

suffer from intolerance to histamine. A diet with a low content

of biogenic amines may improve the condition of these

patients. All patients included in this study evaluated this diet

as having a positive effect on their symptoms.

Because of the uncertainties regarding the benefits and harms

of dietary exclusion in people with atopic dermatitis, Bath-

Hextall et al.

[19]

conducted a systematic review of all relevant

randomized controlled trials. They found some evidence to

support the use of an egg-free diet in infants with suspected

egg allergy and positive specific IgE to eggs in their blood.

Only two of the 11 included studies tested for food

allergy,

[20],[21]

but those studies dealt with comparisons of two

different forms of exclusion diets rather than a comparison of

an exclusion diet vs a normal diet and therefore have not

contributed to the question of whether any form of exclusion

diet is helpful in such people. The other studies included

unselected people with atopic dermatitis did not find any

evidence of benefit for exclusion diets. Elimination diets can be

difficult to follow. The studies reported in the Bath-Hextal et al.

review

[19]

were performed in different populations, with only

one study presenting data on the severity of atopic dermatitis.

The clinical importance of the small changes in severity scores

obtained in many studies is unknown. Although diets excluding

foods such as cow's milk are commonly advised, there is little

evidence in favor of their benefit in unselected people with

atopic dermatitis.

[19]

Future studies should be large enough to answer the questions

posed, and should be reported according to Consolidated

Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)

guidelines.

[22]

Commonsense suggests that food exclusion

studies should be done on people with history suggestive of

food allergy, and positve results should be confirmed by

appropriate allergy testing or challenge tests. A distinction

should be made between young children and adolescents and

adults because food allergy in children tends to improve over

time. Disease severity should be measured using valid

instruments and should include qualityof-life assessments and

patient-centered outcomes that are easy to interpret clinically.

Whereever possible, long-term (>6 months) outcomes should

also be recorded in such studies.

Conclusion

On the basis of our results we recommend the introduction of

this diagnostic hypoallergenic diet as a temporary medical

solution in patients suffering from moderate or severe atopic

dermatitis. This diet can serve as an important diagnostic test

in the workup of food allergy.

References

1. Sampson HA. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2004;113:805-19.

2. Oranje A, De Waard-van der Spek F. Atopic dermatitis and

diet. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000;14:437-8.

3. David TJ, Patel L, Ewing CI, Stanton RH. Dietary factors in

established atopic dermatitis. In: Williams H, editor. The

epidemiology, causes and prevention of atopic dermatitis.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p. 193-

201.

4. Baena-Cagnani C, Teijeiro A. Role of food allergy in asthma

in childhood. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;1:145-

9.

5. Sampson H. The immunopathogenic role of food

hypersensitivity in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol

1992;176:34-7.

6. David TJ, Waddington E, Stanton R. Nutritional hazards of

elimination diets in children with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dis

Child 1984;59:323-5.

7. Devlin J, Stanton RHJ, David TJ. Calcium intake and vows'

milk free diets. Arch Dis Child 1989;64:1183-4.

8. Turjanmaa K. The role of atopy patch tests in the diagnosis

of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin

Immunol 2005;5:425-8.

[PUBMED]

9. Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labrze L, Stalder JF, Ring J, Taieb A.

Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index:

consensus report of the European task Force on Atopic

Dermatitis. Dermatology 1997;195:10-9.

10. Hanifin J, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis.

Acta Derm Venereol 1980;60:44-7.

11. Worth A, Shaikh A. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis. Curr

Opin Allergy and Clin Immunol 2010;10:226-30.

12. Ranc F, Boguniewicz M, Lau S. New visions for atopic

dermatitis: An iPAC summary and future trends. Pediatr

Allergy Immunol 2008;19 (Suppl 19):17-25.

13. Ranc F. Food allergy in children suffering from atopic

dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2008;19:279-84.

14. Werfel T, Ballmer-Weber B, Eigenmann PA, Niggemann B,

Ranc F, Turjanmaa K, et al. Eczematous reactions to food

in atopic dermatitis: Position paper of the EAACI and

GA2LEN. Allergy 2007;62:723-8.

15. Williams JR, Burr ML, Williams HC. Factors influencing

atopic dermatitis - A questionnaire survey of

schoolchildren's perceptions. Br J Dermatol

2004;150:1154-61.

16. Young E, Stoneham MD, Peetruckevitch A, Barton J, Rona

R. A population study of food intolerance. Lancet

1994;343:1127- 40.

17. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food hypersensitivity and atopic

dermatitis: Pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis and

management. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:114-22.

18. Oranje AP, Glazenburg EJ, Wolkerstorfer A, De Waard -van

der Speak FB. Practical issues on interpretation of scoring

atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index, objective SCORAD

and three-item severity score. Br J Dermatol

2007;157:645-8.

19. Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dieaty

exclusions for improving established atopic dermatitis in

adults and children: systemic review. Allergy 2009;64:258-

64.

20. Niggemann B, Binder C, Dupont C, Hadji S, Arvola T,

Isolauri E. Prospective, controlled, multi-center study on the

effect of an amino-acid-based formula in infants with cow's

milk allergy/intolerance and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr

Allergy Immunol 2001;12:78-82.

21. Isolauri E, Sutas Y, Makinen-Kiljunen S, Oja S, Isosomppi

R, Turjanmaa K. Efficacy and safety of hydrolyzed cow milk

and amino acid-derived formulas in infants with cow milk

allergy. J Pediatr 1995;127:550-7.

22. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Lepage L. The CONSORT

statement: Revised recommendations for improving the

quality of reports of parallel group randomised trials. Lancet

2001;357:1191-4.

What is new? The diagnostic hypoallergenic diet can serve as a temporary

medical solution in patients suffering from moderate or severe atopic

dermatitis.

Figures

[Figure 1]

Tables

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3]

This article has been cited by

1 Alimentacin y nutricin: Repercusin en la salud

y belleza de la piel | [Diet and nutrition: Effects on

the skin beauty and health]

Puerto Caballero, L., Tejero Garca, P.

Nutricion Clinica y Dietetica Hospitalaria. 2013;

[Pubmed]

2

Sprvn lba atopick dermatitidy v dtskm

vku | [Treatment of atopic dermatitis in children]

Duchkov, H.

Pediatrie pro Praxi. 2013;

[Pubmed]

About us | Contact us | Sitemap | Advertise | What's New | Feedback | Copyright and Disclaimer

2005 - 2014 Indian Journal of Dermatology | Published by Medknow

Online since 25

th

November '05

ISSN: Print -0019-5154, Online - 1998-3611

V-Bates Shopper

You might also like

- Test-Guided Dietary Exclusions For Treating Established Atopic Dermatitis in Children A Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesTest-Guided Dietary Exclusions For Treating Established Atopic Dermatitis in Children A Systematic ReviewAlfi RahmatikaNo ratings yet

- Out 4Document3 pagesOut 4Musthafa Afif WardhanaNo ratings yet

- B Celiaca Al Toma PDFDocument31 pagesB Celiaca Al Toma PDFSimona JuncuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tugas PDFDocument4 pagesJurnal Tugas PDFIntan Sanditiya AlifNo ratings yet

- Atopic Dermatitis in Infants and Children in IndiaDocument11 pagesAtopic Dermatitis in Infants and Children in IndiaMaris JessicaNo ratings yet

- Thyroid ReviewDocument45 pagesThyroid ReviewSharin K VargheseNo ratings yet

- Food Allergy in EuropeDocument1 pageFood Allergy in EuropehypercyperNo ratings yet

- PIIS1939455119301723Document5 pagesPIIS1939455119301723Yeol LoeyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of CowDocument31 pagesDiagnosis and Management of CowSteluta BoroghinaNo ratings yet

- Togias 2017Document16 pagesTogias 2017Jessica LópezNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1939455122000631 MainDocument25 pages1 s2.0 S1939455122000631 MainWilliam Rolando Miranda ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 14 00475 v3Document12 pagesNutrients 14 00475 v3ellafinarsihNo ratings yet

- Coeliac Disease and Gluten-Related DisordersFrom EverandCoeliac Disease and Gluten-Related DisordersAnnalisa SchiepattiNo ratings yet

- Low Vitamin D Levels Are Associated With Atopic Dermatitis, But Not Allergic Rhinitis, Asthma, or Ige Sensitization, in The Adult Korean PopulationDocument15 pagesLow Vitamin D Levels Are Associated With Atopic Dermatitis, But Not Allergic Rhinitis, Asthma, or Ige Sensitization, in The Adult Korean PopulationJundi Agung SamjayaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Allergy Immunology - 2020 - Foong - Biomarkers of Diagnosis and Resolution of Food AllergyDocument11 pagesPediatric Allergy Immunology - 2020 - Foong - Biomarkers of Diagnosis and Resolution of Food AllergyAlfred AlfredNo ratings yet

- Dhar, 2016 Food Allergy in Atopic DermatitisDocument6 pagesDhar, 2016 Food Allergy in Atopic DermatitisImanuel Far-FarNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On AllergyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Allergyogisxnbnd100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S2213219820303718 MainDocument20 pages1 s2.0 S2213219820303718 Mainrawr rawrNo ratings yet

- Effect of Lactobacillus Sakei Supplementation in Children With Atopic Eczema - Dermatitis SyndromeDocument6 pagesEffect of Lactobacillus Sakei Supplementation in Children With Atopic Eczema - Dermatitis SyndromePutri Halla ShaviraNo ratings yet

- Atopic Dermatitis 2013Document32 pagesAtopic Dermatitis 2013Bagus Maha ParadipaNo ratings yet

- Food Allergy and Atopic Dermatitis: How Are They Connected?Document9 pagesFood Allergy and Atopic Dermatitis: How Are They Connected?Denso Antonius LimNo ratings yet

- Probiotics and Prebiotics in Atopic Dermatitis: Pros and Cons (Review)Document8 pagesProbiotics and Prebiotics in Atopic Dermatitis: Pros and Cons (Review)larissaNo ratings yet

- Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Coeliac DiDocument10 pagesChallenges in Differential Diagnosis of Coeliac DiNäjlãå SlnNo ratings yet

- Probiotics in Pregnant Women To Prevent Allergic Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind TrialDocument8 pagesProbiotics in Pregnant Women To Prevent Allergic Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind TrialarditaNo ratings yet

- The Study of Egg Allergy in Children With Atopic DermatitisDocument5 pagesThe Study of Egg Allergy in Children With Atopic DermatitisranifebNo ratings yet

- Ad 27 355Document9 pagesAd 27 355Hana MitayaniNo ratings yet

- HG 2 PDFDocument5 pagesHG 2 PDFFrandy HuangNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Journal of Parenteral and Enteral: Less or More? Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Septic PatientsDocument4 pagesNutrition Journal of Parenteral and Enteral: Less or More? Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Septic PatientsMarco Antonio BravoNo ratings yet

- Duration of A Cow-Milk Exclusion Diet Worsens Parents ' Perception of Quality of Life in Children With Food AllergiesDocument7 pagesDuration of A Cow-Milk Exclusion Diet Worsens Parents ' Perception of Quality of Life in Children With Food AllergiesM Aprial DarmawanNo ratings yet

- FK Concetration Is Increase in Children With Celic D....Document6 pagesFK Concetration Is Increase in Children With Celic D....Nejc KovačNo ratings yet

- Interpretation and implementation of the revised European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) guidelines on pediatric celiac disease amongst consultant general pediatricians in Southwest of EnglandDocument8 pagesInterpretation and implementation of the revised European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) guidelines on pediatric celiac disease amongst consultant general pediatricians in Southwest of EnglandJephte LaputNo ratings yet

- Clinical SpectrumDocument16 pagesClinical SpectrumArga LabuanNo ratings yet

- Fped 10 945212Document8 pagesFped 10 945212Nejc KovačNo ratings yet

- Annals EczemaDocument16 pagesAnnals EczemaewbNo ratings yet

- Clinical Spectrum of Food Allergies: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument16 pagesClinical Spectrum of Food Allergies: A Comprehensive ReviewAmalia Cipta SariNo ratings yet

- Fped 06 00350Document19 pagesFped 06 00350Jake DagupanNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Personalized Nutrition Approach in Food Allergy: Is It Prime Time Yet?Document16 pagesNutrients: Personalized Nutrition Approach in Food Allergy: Is It Prime Time Yet?Meisya Nur'ainiNo ratings yet

- Atopic DermatitisDocument31 pagesAtopic DermatitisityNo ratings yet

- Medical News in The World of Atopic Dermatitis First Quarter 2016Document5 pagesMedical News in The World of Atopic Dermatitis First Quarter 2016anon_384025255No ratings yet

- Allergic Disease - Probiotics and PrebioticsDocument13 pagesAllergic Disease - Probiotics and PrebioticsMihaela AcasandreiNo ratings yet

- Apical Periodontitis and Diabetes Mellitus Type 2Document11 pagesApical Periodontitis and Diabetes Mellitus Type 2Mihaela TuculinaNo ratings yet

- The Link Between The Clinical Features o PDFDocument2 pagesThe Link Between The Clinical Features o PDFwulanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DA 9Document8 pagesJurnal DA 9FIFIHNo ratings yet

- Celiac Disease New Approaches To Therapy: A ReviewDocument14 pagesCeliac Disease New Approaches To Therapy: A ReviewCeliacDesiNo ratings yet

- Enteropatia EosinofilicaDocument6 pagesEnteropatia EosinofilicaLuisa Maria LagosNo ratings yet

- Check Unit 555 November Immunology V3 PDFDocument25 pagesCheck Unit 555 November Immunology V3 PDFdragon66No ratings yet

- Allergy - 2014 - Muraro - EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Diagnosis and Management of Food AllergyDocument18 pagesAllergy - 2014 - Muraro - EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Diagnosis and Management of Food AllergyCatherinavcuNo ratings yet

- Group 5 Pubmed Accepted Results PDFDocument683 pagesGroup 5 Pubmed Accepted Results PDFDnyanesh LimayeNo ratings yet

- 2011 NIAIDSponsored 2010 Guidelines For Managing Food Allergy Applications in The Pediatric PopulationDocument13 pages2011 NIAIDSponsored 2010 Guidelines For Managing Food Allergy Applications in The Pediatric PopulationLily ChandraNo ratings yet

- Abses PayudaraDocument18 pagesAbses Payudaragastro fkikunibNo ratings yet

- Alergia AlimentariaDocument18 pagesAlergia AlimentariaLUIS PARRANo ratings yet

- Food Allergy - JCDocument20 pagesFood Allergy - JCHani GowaiNo ratings yet

- Alison ReidDocument28 pagesAlison ReidAnonymous KoDfgLZtimNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Food Allergy: Immune Mechanisms, Diagnosis and ImmunotherapyDocument43 pagesHHS Public Access: Food Allergy: Immune Mechanisms, Diagnosis and ImmunotherapyLeonardo AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Atención de Los Niños Con Alergias A FármacosDocument5 pagesAtención de Los Niños Con Alergias A FármacosHugo RoldanNo ratings yet

- Oral Food Challenges in Children With A Diagnosis of Food AllergyDocument7 pagesOral Food Challenges in Children With A Diagnosis of Food Allergyastuti susantiNo ratings yet

- Etanercept Treatment For ChildrenDocument21 pagesEtanercept Treatment For ChildrenSitti Nurdiana DiauddinNo ratings yet

- Lay Prevalence Paper FinalDocument5 pagesLay Prevalence Paper Final강동희No ratings yet

- Abstract 2010 LourençoDocument1 pageAbstract 2010 LourençoAna Cristina SilvaNo ratings yet

- PDF Jurnal Kulit 2 - Oom JhonDocument5 pagesPDF Jurnal Kulit 2 - Oom JhonFebniNo ratings yet

- PhototherapyonPsoriasis-Prof DR Med IsaakEffendyDocument1 pagePhototherapyonPsoriasis-Prof DR Med IsaakEffendyFebniNo ratings yet

- Immunological Aspects of GastrointestinalDocument12 pagesImmunological Aspects of GastrointestinalFebniNo ratings yet

- Appi Ajp 2010 10040541Document9 pagesAppi Ajp 2010 10040541FebniNo ratings yet

- PDF GDocument3 pagesPDF GFebniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Morbili Lp..Document11 pagesJurnal Morbili Lp..FebniNo ratings yet

- Appi Ajp 2010 09050627Document8 pagesAppi Ajp 2010 09050627FebniNo ratings yet

- Olive Oil: A Good Remedy For Pruritus Senilis: Short CommunicationDocument4 pagesOlive Oil: A Good Remedy For Pruritus Senilis: Short CommunicationFebniNo ratings yet

- Electrocardiograph Changes in Acute Ischemic Cerebral StrokeDocument6 pagesElectrocardiograph Changes in Acute Ischemic Cerebral StrokeFebniNo ratings yet

- Pedoman PenilainDocument4 pagesPedoman PenilainFebniNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2090074013000790Document3 pagesPi Is 2090074013000790FebniNo ratings yet

- Electrocardiograph Changes in Acute Ischemic Cerebral StrokeDocument6 pagesElectrocardiograph Changes in Acute Ischemic Cerebral StrokeFebniNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Resistance To Antibiotics in Acne Vulgaris: An In: Vitro StudyDocument5 pagesBacterial Resistance To Antibiotics in Acne Vulgaris: An In: Vitro StudyFebniNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of The Efficacy of 4% Hydroquinone Vs 0.75% Kojic Acid Cream in The Treatment of Facial MelasmaDocument6 pagesA Comparative Study of The Efficacy of 4% Hydroquinone Vs 0.75% Kojic Acid Cream in The Treatment of Facial MelasmaFebniNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of 2% Metronidazole Gel in Moderate Acne Vulgaris: Therapeutic RoundDocument5 pagesEfficacy of 2% Metronidazole Gel in Moderate Acne Vulgaris: Therapeutic RoundFebniNo ratings yet

- Childhood Vitiligo: Response To Methylprednisolone Oral Minipulse Therapy and Topical Fluticasone CombinationDocument5 pagesChildhood Vitiligo: Response To Methylprednisolone Oral Minipulse Therapy and Topical Fluticasone CombinationFebniNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology RoundDocument13 pagesEpidemiology RoundFebniNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic RoundDocument6 pagesTherapeutic RoundFebniNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Roun2Document5 pagesTherapeutic Roun2FebniNo ratings yet

- Long Standing Tracheal Foreign Body in ChildrenDocument12 pagesLong Standing Tracheal Foreign Body in ChildrenFebniNo ratings yet

- HTTPDocument6 pagesHTTPFebniNo ratings yet

- Dr. Agustina, SP - An, TenggelamDocument19 pagesDr. Agustina, SP - An, TenggelamrajaalfatihNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology Roun1Document10 pagesEpidemiology Roun1FebniNo ratings yet

- ScanDocument1 pageScanFebniNo ratings yet

- TC AdvisoryDocument1 pageTC AdvisoryJerome DelfinoNo ratings yet

- 9446 - Data Sheets Final PDFDocument17 pages9446 - Data Sheets Final PDFmarounNo ratings yet

- Icpc11 - Thermodynamics and Fluid MechanicsDocument22 pagesIcpc11 - Thermodynamics and Fluid MechanicsAPARNANo ratings yet

- Med Chem Exam 2Document24 pagesMed Chem Exam 2cNo ratings yet

- Stress Management PPT FinalDocument7 pagesStress Management PPT FinalAdarsh Meher100% (1)

- Nano ScienceDocument2 pagesNano ScienceNipun SabharwalNo ratings yet

- Hygiene PassportDocument133 pagesHygiene PassportAsanga MalNo ratings yet

- The Finite Element Method Applied To Agricultural Engineering - A Review - Current Agriculture Research JournalDocument19 pagesThe Finite Element Method Applied To Agricultural Engineering - A Review - Current Agriculture Research Journalsubhamgupta7495No ratings yet

- Transfer Case Electrical RMDocument51 pagesTransfer Case Electrical RMDaniel Canales75% (4)

- Karan AsDocument3 pagesKaran AsHariNo ratings yet

- Acer AIO Z1-752 System DisassemblyDocument10 pagesAcer AIO Z1-752 System DisassemblySERGIORABRNo ratings yet

- Digital Trail Camera: Instruction ManualDocument20 pagesDigital Trail Camera: Instruction Manualdavid churaNo ratings yet

- AC350 Specs UsDocument18 pagesAC350 Specs Uskloic1980100% (1)

- +chapter 6 Binomial CoefficientsDocument34 pages+chapter 6 Binomial CoefficientsArash RastiNo ratings yet

- Logistics Operation PlanningDocument25 pagesLogistics Operation PlanningLeonard AntoniusNo ratings yet

- Mercedez-Benz: The Best or NothingDocument7 pagesMercedez-Benz: The Best or NothingEstefania RenzaNo ratings yet

- Eoi QAMDocument6 pagesEoi QAMPeeyush SachanNo ratings yet

- HBT vs. PHEMT vs. MESFET: What's Best and Why: Dimitris PavlidisDocument4 pagesHBT vs. PHEMT vs. MESFET: What's Best and Why: Dimitris Pavlidissagacious.ali2219No ratings yet

- Aerodrome Advisory Circular: AD AC 04 of 2017Document6 pagesAerodrome Advisory Circular: AD AC 04 of 2017confirm@No ratings yet

- Your Heart: Build Arms Like ThisDocument157 pagesYour Heart: Build Arms Like ThisNightNo ratings yet

- Avionic ArchitectureDocument127 pagesAvionic ArchitectureRohithsai PasupuletiNo ratings yet

- Over Current & Earth Fault RelayDocument2 pagesOver Current & Earth Fault RelayDave Chaudhury67% (6)

- Daoyin Physical Calisthenics in The Internal Arts by Sifu Bob Robert Downey Lavericia CopelandDocument100 pagesDaoyin Physical Calisthenics in The Internal Arts by Sifu Bob Robert Downey Lavericia CopelandDragonfly HeilungNo ratings yet

- General Anaesthesia MCQsDocument5 pagesGeneral Anaesthesia MCQsWasi Khan100% (3)

- Mathematics For Engineers and Scientists 3 PDFDocument89 pagesMathematics For Engineers and Scientists 3 PDFShailin SequeiraNo ratings yet

- Smart Watch User Manual: Please Read The Manual Before UseDocument9 pagesSmart Watch User Manual: Please Read The Manual Before Useeliaszarmi100% (3)

- Notice: Environmental Statements Notice of Intent: Eldorado National Forest, CADocument2 pagesNotice: Environmental Statements Notice of Intent: Eldorado National Forest, CAJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Present Arlypon VPCDocument1 pagePresent Arlypon VPCErcan Ateş100% (1)

- Feature Writing EnglishDocument2 pagesFeature Writing EnglishAldren BababooeyNo ratings yet

- ONGC Buyout GOI's Entire 51.11% Stake in HPCLDocument4 pagesONGC Buyout GOI's Entire 51.11% Stake in HPCLArpan AroraNo ratings yet