Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kepler Somnium 1634 Sammanfattning

Uploaded by

Javier Arturo67%(3)67% found this document useful (3 votes)

93 views21 pagesSomnium is a fantasy written between 1620 and 1630 by Johannes Kepler. It is considered the first serious scientific treatise on lunar astrono#y. The manuscript had been the elder Kepler's constant companion since his student days at #bin!en %niversity.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSomnium is a fantasy written between 1620 and 1630 by Johannes Kepler. It is considered the first serious scientific treatise on lunar astrono#y. The manuscript had been the elder Kepler's constant companion since his student days at #bin!en %niversity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

67%(3)67% found this document useful (3 votes)

93 views21 pagesKepler Somnium 1634 Sammanfattning

Uploaded by

Javier ArturoSomnium is a fantasy written between 1620 and 1630 by Johannes Kepler. It is considered the first serious scientific treatise on lunar astrono#y. The manuscript had been the elder Kepler's constant companion since his student days at #bin!en %niversity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 21

Somnium (Latin for The Dream) is a fantasy written between 1620 and 1630 by

Johannes Kepler in which a student of Tycho Brahe is transported to the oon by

occult forces! "t is considered the first serious scientific treatise on lunar

astrono#y!

Somnium be$an as a student dissertation in which Kepler defended the

%opernican doctrine of the #otion of the &arth' su$$estin$ that an obser(er on

the oon would find the planet)s #o(e#ents as clearly (isible as the oon)s

acti(ity is to the &arth)s inhabitants! *early 20 years later' Kepler added the

drea# fra#ewor+' and after another decade' he drafted a series of e,planatory

notes reflectin$ upon his turbulent career and the sta$es of his intellectual

de(elop#ent! The boo+ was edited by his heirs' includin$ Jacob Bartsch' after

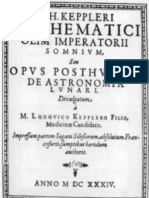

Kepler)s death in 1630' and was published posthu#ously in 163-!

Kepler's Somnium: Science Fiction and the Renaissance

Scientist

In 1634, four years after his death, the most provocative and innovative of Johannes Keplers

works was published by his son udwi! Kepler, then a candidate for the doctorate in

medicine" In one form or another, the manuscript had been the elder Keplers constant

companion since his student days at #$bin!en %niversity where his introduction to the

heliocentric system, revived from the ancient &reeks by the 'olish astronomer (icholas

)opernicus, had prompted Kepler to devote one of his re*uired dissertations to the *uestion+

,-ow would the phenomena occurrin! in the heavens appear to an observer stationed on the

moon., #he theses propounded by Kepler at #$bin!en in 1/03 contained, in the words of his

&erman bio!rapher 1a2 )aspar, ,the first !erm of a work which we shall come to know as

the last of the books he published,, the Somnium or Dream"

1

It had been Keplers intent to personally supervise the publication of his manuscript and, at

the time of his sudden death in 1633, si2 pa!es of the document were in type" Jacob 4artsch,

Keplers son5in5law, undertook the task of completin! publication but he, too, died suddenly

before it was finished" #he pro6ect mi!ht well have been abandoned at this point had not

Kepler left his widow in dire financial straits" In an attempt to assist his mother durin! this

economic crisis, son udwi! brou!ht the thin volume to press in 1634" In accordance with the

medieval5classical tradition7broken only by Keplers contemporary &alileo, who

occasionally published in the vernacular7the ori!inal edition was in atin" 8ver two

centuries passed before a second atin edition was published in 19:3 in volume ei!ht of the

Opera Omnia, a collection of Keplers works edited by )hristian ;risch" #his was followed in

1909 by a rather poor and *uite obscure &erman paraphrase under the title Keplers Traum

Von Mond by udwi! &unther" <2cept for these two limited editions and a few survivin!

copies of the ori!inal printin!, a seminal work in science fiction remained a literary curiosity

for over three centuries, read only by those few authors with a stron! interest in the new !enre

and possessed of the classical back!round re*uired to read the work in its ori!inal atin"

It is difficult to appreciate to any de!ree this last work of a !reat theoretician and scientist

without knowin! somethin! of the circumstances surroundin! its authorship, a task which

spanned some thirty5seven years" ;or the time in which he lived Keplers lunar e2ploration is

a truly remarkable and revolutionary work, and in the view of historian ewis 1umford must

be appreciated for ,the audacity of the concept, as well as for its intrinsic merit as a

pioneerin! work of science fiction"

=

#here is little, if anythin!, in the back!round and early childhood of Johannes Kepler to

su!!est that this son of a neer5do5well mercenary of the >uke of ?lba and an innkeepers

dau!hter, who was nearly burned at the stake as a witch, would become a central fi!ure in the

seventeenth5century scientific revolution in astronomy" Kepler was born and spent his

childhood in @eil5der5Atadt, a small Awabian villa!e located in southwestern &ermany" -e

lived in the crowded cotta!e home of his paternal !randfather, Aebaldus Kepler, alon! with

aunts, uncles and numerous brothers and sisters7the latter of whom bio!rapher ?rthur

Koestler collectively refers to as ,this misshapen pro!eny",

3

#hrou!h some favorable natural phenomena, not yet completely understood by modern

science, Johannes was endowed at birth with the !ift of !enius while the rest of his brothers

and sisters suffered from severe mental and physical handicaps" Kepler, himself, was not

entirely immune to the family curse of physical infirmity, for he was bow5le!!ed, fre*uently

covered with lar!e boils, and suffered from con!enital myopia and multiple vision" #he latter

affliction must have been particularly distressin! to one whose love of the heavens defined his

career" Johannes special intellectual endowment was apparent from an early a!e however,

and fortunately those responsible for his education wanted the !ift to be as fully developed as

possible" )onse*uently, Kepler was enrolled at #$bin!en %niversity, and it was there that the

first seeds of the Somnium, published some forty years later, were sown"

Kepler was an e2cellent student in all fields of study includin! theolo!y, but he worked most

dili!ently and happily on astronomical *uestions" It was his !ood fortune to matriculate while

1ichael 1aestlin, one of the most learned and esteemed astronomers of the time, was a

member of the #$bin!en faculty" In deference to the teachin!s of 1artin uther and 'hillip

1elanchton, uthers advisor on scientific matters, 1aestlin, at least in his public lectures,

advocated the !eocentric system of planetary motion as described by the second century

&reek astronomer )laudius 'tolemy in his influential treatise the Almagest"

4

)opernican

theory, even when tau!ht on the speculative basis permitted by the Boman )atholic )hurch

until &alileos trial in 1633, was strictly prohibited at the outset by the utheransC and amon!

his theolo!ical collea!ues 1aestlin was the only advocate of the new astronomy" 'rivately,

however, 1aestlin did discuss the heliocentric universe, and apparently his early reco!nition

of Keplers !enius persuaded 1aestlin to admit his student to that small circle of intimates

who shared his views" ,In the youthful enthusiastic head of his pupil the spark i!nited"

1aestlins considerations and repressions were alien to the youn! and unencumbered Kepler

who, open and dauntless, entered into disputation in favor of the new astronomical theory",

/

Kepler also learned a !ood deal of practical astronomy from 1aestlin, includin! the ancient

&reek techni*ue of estimatin! elevations on the moons surface by measurin! the shadows

cast by these protuberances" ?nd he be!an to !rapple with the *uestion put at the be!innin! of

this paper of how the heavens would appear to an observer standin! on the moon" Kepler

knew from studyin! )opernicus that the earth is movin! very rapidly" Det those who inhabit

the planet are unaware of this rapid movement because they are not able to detect it throu!h

the use of their senses" Kepler *uite lo!ically reasoned that a man standin! on the moon

would share an identical e2perienceC he could see the earth chan!e position because he would

not be a participant in its rotation 6ust as a moonwatcher on earth observes lunar motion in

which he does not participate" #his realiEation and the comple2 issues it raised became the

basic theme of Keplers dissertation of 1/03 and, *uite inadvertently, the !enerative force

underlyin! the first work of modern science fiction"

-ad the #$bin!en faculty been more tolerant of the new astronomy, the theses presented in

Keplers dissertation would have been publicly debated and probably lon! for!otten"

-owever when the proposal was presented to the authorities for their approval, they vetoed

the debate" 8ne of Keplers closest friends and a fellow student, )hristoph 4esold, who later

became a noted professor of law at #$bin!en, appealed to his professor and advisor, Fitus

1$ller, to permit him, rather than Kepler, to uphold the theses in a disputationC but after

considerin! the matter, 1$ller refused" #he fact that 4esold re*uested to debate Keplers

theses su!!usts that the authorities mi!ht have known of the close Kepler51aestlin

relationship, and that Kepler and his friend considered it more likely that 1$ller and his

collea!ues would reach a favorable verdict if 4esold, a law student, led the debate"

Kepler was no doubt disappointed and perhaps even somewhat bitter about the decisionC yet

he was also realistic enou!h to know that to further protest his fate, when even his hi!hly

respected professor of astronomy was condemned to public silence on matters )opernican,

would be foolhardy and perhaps dama!in! to his career" Atill, there was sufficient !rit to

produce a pearl" Kepler wisely decided to keep his manuscript until the time when a more

favorable climate of opinion mi!ht prevail" -e also wanted to do more research, particularly

on the &reek classics, and to discover any possible precedents in them that would make his

work more palatable to the ?ristotelians"

#he student dissertation of 1/03 was left untouched by its author for the ne2t si2teen years"

1eanwhile, Keplers career as a mathematician5astronomer flourished" -e was !raduated

from the ;aculty of ?rts at #$bin!en at the a!e of twenty and enrolled at the #heolo!ical

;aculty of the %niversity to continue preparin! for his chosen vocation7that of a utheran

cler!yman" -is reputation as an e2cellent mathematician followed him howeverC and the

#$bin!en Aenate offered Kepler the position of teacher of mathematics and astronomy in

&ratE, the sleepy capital of the ?ustrian province of Atyria" ;earin! himself unworthy of such

a post, Kepler reluctantly accepted the offer only after considerable coa2in!+ his plans for a

career in theolo!y were permanently abandoned" #he choice proved a !ood oneC the youn!

mathematician became a respected teacher and he apparently en6oyed his new surroundin!s,

for Kepler remained in &ratE until January of 1633" #he rather obscure town provided few

distractions from scholarly pursuits, and, since his classes were small, Kepler had

considerable free time to devote to mathematics and astronomy"

?t the a!e of twenty5five he published his first book, the Mysterium Cosmographicum, which

is a brilliant if hi!hly mystical and error5prone amal!am of ?ristotelian and )opernican

cosmolo!y"

6

#he work attracted the attention of the !reat >anish astronomer, #ycho 4rahe,

who was deeply impressed by Keplers synthesis of the old and new astronomy"

:

#his

favorable impression ultimately led 4rahe to offer Kepler a position as his assistant after the

>ane was appointed Imperial 1athematician by the -oly Boman <mperor, Budolph II"

Kepler worked with 4rahe from early 1633 until the latters death in (ovember 1631, after

which Kepler succeeded to the post of his teacher" <*ually important is the fact that after a

s*uabble with #ychos heirs, Kepler inherited the astronomers observational data,

unparalleled for its accuracy, on the oppositions of 1ars between 1/93 and 1633" It was

throu!h the mathematical analysis of 4rahes observations that Kepler arrived at his famous

law of ellipses in 163/" #he conclusions derived from this law provided the basis for his most

important scientific work, Astronomia Nova, published in 1630, the same year in which his

interest in the for!otten dissertation of his student days was rekindled"

In his capacity as Imperial 1athematician Kepler resided in 'ra!ue, then the capital of the

-oly Boman <mpire" >urin! the summer of 1630, he became involved in a series of lon!

conversations with his friend and ecclesiastical advisor to <mperor Budolph, @ackher von

@ackenfels" Budolph had asked Kepler his views re!ardin! the patterns of li!ht and shadows

appearin! on the lunar surface+ the emperor had personally concluded that they are formed by

the reflection off the moon of ma6or land masses located on the earth" In effect, Budolph was

advocatin! a somewhat modified version of the ?ristotelian position and he wanted to know

if Kepler a!reed with him"

Kepler, of course, did not a!ree with his patron because as far back as his student days he had

known that the shadows on the moon were caused by mountains or other natural

outcroppin!s" It was a conclusion reinforced by years of additional study and observation both

on his own and under #ychos tutela!e" @hile not an e2pert on the matter himself, @ackher

was interested in Keplers views and encoura!ed his friend to publish them" Keplers lifelon!

intri!ue with lunar !eo!raphy combined with @ackhers interest resulted in the composition

of the Somnium, a !reatly modified version of his student dissertation"

9

#here can be little, if any, doubt that Kepler selected the framework of the Dream to satisfy

two ma6or demands+ first, fewer ob6ections could be raised amon! the ranks of those still

within the ?ristotelian orbit by passin! off this )opernican treatise as a fi!ment of an idle

slumberers uncontrollable ima!inationC and secondly, it enabled Kepler to introduce a

mythical a!ent or power capable of transportin! humans to the lunar surface" In fact to the

cursory reader, Kepler must have appeared more mytho!rapher than speculative scientist, and

this is the very impression the author intended"

0

#he Somnium be!ins like a classical le!end and relates the authors ,dream, about the

adventures of a youn! man, >uracotus, a native of an island called ,#hule, by the ancients,

Iceland by seventeenth5century <uropeans" >uracotus father, a fisherman by trade, died at

the e2tremely advanced a!e of 1/3, but the child was still too youn! to have any recollection

of him" ;iol2hilde, the mother, is a ,wise woman,, who supports both her son and herself by

!atherin! herbs which are then cooked, stuffed in little ba!s of !oatskin, and sold at a nearby

port to sailors" #he ba!s supposedly harbor mysterious lucky charms and the healin! powers

re*uired by seamen on the lon! and always dan!erous voya!es across the north ?tlantic" 8ne

day, out of curiosity,, >uracotus cut open one of the ba!s his mother intended to sell to a

ships captain, scatterin! its contents on the !round" In a fit of an!er ;iol2hildes temper !ot

the best of her and she sold her son to the captain in place of the lost herbs"

#he followin! day, the captain set sail for (orway but he stopped in >enmark to deliver a

letter from a bishop in Iceland to the astronomer #ycho 4rahe, who then resided on the island

of -veen in the Aund between )openha!en and <lsinore )astle" >uracotus became *uite ill

durin! the voya!e Gapparently he carried no ba! of his mothers charmsH, and he was put

ashore when #ychos letter was delivered" #he astronomer *uestioned the boy at some len!th,

considered him to be *uite intelli!ent, and undertook to train him in the science of astronomy"

>uracotus response is enthusiastic+ ,I was deli!hted beyond measure by the astronomical

activities, for 4rahe and his students watched the moon and the stars all ni!ht with marvelous

instruments",

13

?fter spendin! five years in #ychos company >uracotus took his masters leave and sailed

for home" -e found ;iol2hilde much as she was when he left, e2cept that the old woman had

suffered terribly as a result of her impetuosity and was over6oyed to see her son alive and

well" ? number of lon! discussions ensued durin! which ;iol2hilde e2pressed happiness over

>uracotus ac*uaintance with the new science of the stars" Ahe confesses to her own special

knowled!e of the heavens and the fact that her teacher is none other than the ,>aemon of

avania,7the spirit of the moon" ,1ost of the thin!s which you saw with your own eyes or

learned by hearsay or absorbed from books, he related to me as you did", #he mother then

reveals her ultimate secret+ it is possible, with the assistance of the >aemon, to travel to

avania and, *uite predictably, she asks her son to accompany her on 6ust such a lunar

voya!e" >uracotus consents and ,as soon as the sun set below the horiEon, and was in

con6unction with the planet Aaturn in the si!n of the 4ull, ;iol2hilde summoned the >aemon

and seated herself ne2t to her son who covered their heads with a blanket" @ithin a few

moments the 6ourney of ,fifty thousand &erman miles, had be!un, up throu!h the ethereal

re!ions to the moon"

%p to this point there is little which separates the Aomnium from a lon! literary tradition

rooted in the ima!ination of the ancient &reeks" ?fter his rebuff at the hands of the #$bin!en

faculty Kepler had purchased a copy of ucians satirical work on lunar e2ploration

facetiously titled, A True Story" ;rom a scientific point of view the work made no sense+

ucians voya!e to the moon be!ins in a whirlwind and concludes by pokin! fun at the

society of his day throu!h a chronicle of ,hilarious discussions on the moon", #he fli!ht of

>uracotus and ;iol2hilde is also the result of supernatural forces that are no less mystical than

the whirlwind con6ured up by ucian"

? second, and more important source of inspiration for Keplers moon voya!e was 'lutarchs

The Face on the Moon, which Kepler read in 1/0/" It is a symposium of &reek scientific

thou!ht that includes the views of -ipparchus, ?ristotle, and ?ristarchus of Aamos" <2tensive

speculation on the lunar environment as a possible home for life is presentedC and 'lutarch

even relates the story of a mythical traveler7a &reek >uracotus7who sails to an island

whose residents have knowled!e of the passa!e to the moon"

1=

Kepler now had the classical

precedent he lacked durin! his student days+ he even hoped to publish translations both of

ucians and 'lutarchs work with the Somnium to show his debt to these classical writers,

and hopefully blunt potential criticism of his own moon voya!e"

13

It was a task he did not

complete"

@hile Keplers method of fli!ht to the moon is not markedly different from that outlined by

ucian, and althou!h much of his inspiration for lunar e2ploration is undeniably 'lutarchian,

the Aomnium represents a sharp break with classical traditionC the first intimation of which

occurs durin! the voya!e itself" @e are informed that the fli!ht of four hours is ,most difficult

and frau!ht with the !reatest dan!er to life", 8nly those who are slender of body are

acceptable, thus rulin! out most &erman males whose !eneral corpulence was apparently

distasteful to the slender Kepler" In 6est Kepler carried the matter further by pointin! out the

>aemons preference for ,dried5up old women, e2perienced from an early a!e in ridin! he5

!oats at ni!ht or forked sticks or threadbare cloaks", It was to prove a most costly 6oke for, as

we shall see, it later backfired on its author whose own mother was accused of practicin!

witchcraft by superstitious nei!hbors and nearly burned at the stake by the authorities"

#he take5off for the moon hits the traveler as a severe shock, ,for he is hurled 6ust as thou!h

he had been shot aloft by !unpowder to sail over mountains and seas", In order to counteract

what Isaac (ewton would later define as the force of !ravity, the moon voya!ers are put to

sleep with the aid of opiates and their limbs are arran!ed in such a way that their bodies will

not be torn apart by the force of acceleration"

14

Aince breathin! is inhibited by the swift

passa!e of e2tremely cold air throu!h the nostrils, damp spon!es are applied to the face"

@ithin a short time the speed of fli!ht becomes so !reat that the body involuntarily rolls itself

up into a ball like an endan!ered spider and ,we are carried alon! almost entirely by our will

alone, so that finally the bodily mass proceeds toward its destination of its own accord+,

Kepler had introduced the concept of ,inertia, to the physical sciences and had e2tended its

operation into the heavens"

Kepler anticipates another ma6or obstacle to the moon voya!er when he observes that we

a!reed not to be!in ,until the moon be!ins to be eclipsed on its eastern side" Ahould it re!ain

its full li!ht while we are still in transit, our departure becomes futile", In other words, Kepler

knew that once outside the protective blanket provided by the earths atmosphere, humans

could not survive the resultin! solar bombardment+ the fli!ht must be!in at the critical

moment when the sun is behind the earth or at a point directly opposite the point of take5off"

>urin! a lunar eclipse the earths shadow would provide the tunnel of darkness re*uired to

protect the vulnerable moon voya!erC and it is not by accident that the ma2imum duration of

such an eclipse is four and one5half hours, 6ust one5half hour more than the duration of the

voya!e itself"

1/

? further indication of Keplers mastery of )opernican astronomy is his

understandin! that since the earth and the moon are both in motion, the shortest route to the

latter would not be the strai!ht line advocated by such ancient writers of mytholo!y as

ucian, but a tra6ectory from earth to a point in space where the moon and the lunar voya!ers

would arrive simultaneously"

16

Kepler also relates that many additional difficulties arise durin! the lunar voya!e which are

too tedious to enumerate" @e are already aware, however, that Kepler possessed a keen !rasp

of the most serious obstacles to lunar fli!ht and that even thou!h those obstacles were beyond

solution in terms of the technolo!ical e*uipment of his a!e, he believed it was at least

theoretically possible7from a scientific point of view7for men to reach the moon" It is this

attitude that sets Kepler apart from all the others who considered the possibility of lunar fli!ht

before him"

%pon reachin! the surface of avania the voya!ers are weary, but soon recover sufficiently to

walk about" #he >aemon immediately !uides his char!es to a cave in order to protect them

from the penetratin! rays of the risin! sun" #here they meet other daemons and have the

opportunity to recuperate from the effects of their arduous 6ourney before be!innin! a

reconnaissance of the moons !eo!raphy, flora, and fauna" #hey are informed by their

spiritual hosts that avania consists of two hemispheres+ Aubvolva and 'rivolva" Aubvolva

always has its Folva G<arthH above which corresponds to the earths satellite, the moon, while

'rivolva is forever deprived of the si!ht of Folva"

1:

#aken to!ether, a ni!ht and a day on

avania are e*uivalent to one month on earth providin! alternatin! two5week periods of

intense, scorchin! heat followed by a cold unima!inable on this planet" #he e2tremes of

temperature in the Aubvolvan hemisphere are miti!ated to some e2tent because of Folvas

presence which has a moderatin! influence on the climate" &eo!raphically, the surface of the

moon possesses everythin! that is on earth, but on a !rossly e2a!!erated scale+ the mountains

reach unbelievable hei!hts while the fissures, valleys, and craters plun!e to precipitous depths

unknown in the terrestrial realm"

8f e*ual interest to the student of science fiction is Keplers detailed analysis of the life forms

that inhabit avania" -is powers of scientific deduction were matched by a fertile and realistic

ima!ination when postulatin! biolo!ical conditions on the moon" ?lthou!h he was trained as

an astronomer and mathematician, Kepler was too !ood a scientist not to understand that the

dual effects of the lunar climate and the irre!ular, hostile terrain would produce plants and

animals far different from those that inhabit the earth" -e re6ected the temptation, which

others had not, of simply recreatin! a terrestrial civiliEation on the moonC for in Keplers

avania there are no men and women, no civiliEation as he knew it" #hus nearly two centuries

before 4uffon, yell, and >arwin, Kepler had !rasped the close interrelationship between life

forms and their natural environment"

@hatever is born on the moon attains a monstrous siEe+ !rowth is e2tremely rapid, dictatin! a

very short life span by terrestrial standards" Aince there are no towns the ,'rivolvans have no

fi2ed abode, no established domicile", #hey are nomadic creatures who roam in crowds over

their entire hemisphere+

Aome use their le!s, which far surpass those of our camelsC some resort to win!sC and some follow the

recedin! water in boatsC or if a delay of several more days is necessary, then they crawl into caves"

1ost of them are diversC all of them draw their breath very slowlyC hence under water they stay down

on the bottom"

Kepler considered the natural protection of lar!e bodies of water and of caves as

indispensable to an environment whose temperatures far e2ceed those of the hottest re!ions

on earth" ?nd althou!h he does not elaborate on the sub6ect, he su!!ests that the lunar

inhabitants are not the dumb animals they mi!ht at first appear to be" #heir ability to construct

boats to escape the far5reachin! effects of the sun provides evidence of this"

;eedin! is a nocturnal function which, if prolon!ed until after sunrise, often leads to death"

#he skin of the moon5dwellers, the ma6ority of whom resemble massive serpents, is spon!y

and porous and, if e2posed to the full force of the sun, becomes scorched and brittle" ;ood

consists primarily of plants whose surface ,is like rind, and of the carcasses of the lar!e

number of creatures who die each day" Auch is the !i!antic race of short5lived creatures that

the historian of literature 1ar6orie -ope (icolson likened to those of the antediluvian a!e on

earth+ lunar pterodactyls or ichthyosauri that bask for a brief moment in the risin! or settin!

sun, then creep forever into the impenetrable avanian darkness"

19

?t this point the Aomnium comes to a rather abrupt and premature conclusion" Kepler informs

us that, ,? wind arose with the rattle of rain" I returned to find myself and found my head

really covered with the pillow and my body with the blankets,, an allusion, no doubt, to the

be!innin! of the moon voya!e when >uracotus and ;iol2hilde covered their heads prior to the

take5off"

#he actual te2t of the Aomnium, e2clusive of the len!thy footnotes which were completed

several years later and represent the third and final sta!e of composition, comprises only

about twenty type5written pa!es" -ad the work been published at this point it would have

been a slender volume indeedC but Kepler clun! to his plan to publish it in con6unction with

translations of 'lutarch and ucian, and then only after it had been circulated amon! his most

trusted collea!ues in manuscript form" ?s was noted above, Keplers primary concern was

with the opposition he mi!ht provoke amon! the ?ristoteliansC he wanted some idea of the

type of reception he could e2pect"

In 1613, a few months after the te2t of the Somnium was completed, Kepler received some

welcome and e2citin! news from Italy" -is fellow scientist, &alileo &alilei, had constructed a

number of telescopes and had used them to observe celestial phenomena not visible to the

naked eye" #he astoundin! results were published in &alileos revolutionary little work, The

Starry Messenger, in which the Italian astronomer announced the discovery of sunspots,

Jupiters four moons, countless ,new, stars, and most importantly7from Keplers point of

view7the mountains and craters of the moon" -ere was visual confirmation of much of what

Kepler had theoriEed in the Somnium, and it marked the be!innin! of the end of ?ristotelian

cosmolo!y" Det Kepler, unlike the overly euphoric &alileo, was realistic enou!h to know that

the new discoveries, no matter how revolutionary and enli!htenin!, would not brin! about an

immediate and universal acceptance of )opernicanism, but at least the ?ristotelians were

clearly on the defensive" ?t this point the future of the new astronomy and of the Somnium

looked almost as bri!ht as the new stars seen for the first time throu!h &alileos telescope"

#he lunar !eo!raphy was probably read privately in manuscript form for the last time in 1613"

#hrou!h a rather complicated and unfortunate series of events, Kepler lost control of a copy

in 1611 and a number of individuals7many of them unknown to Kepler personally7!ained

access to it, includin! some that the author would not have approved of" #he Somnium was

written for scientists and was little understood, e2cept on the most superficial level, by those

lackin! a scientific back!round" Kepler su!!ests that it became the sub6ect of !ossip in the

tonstrinae, the forerunner to the modern coffeehouse"

10

Aome of those who knew Kepler and

his family, or at least thou!ht they did, discovered sufficient autobio!raphical material in the

manuscript to feed the fires of i!norance and superstition then en!ulfin! &ermany" #hey

e*uated Johannes with >uracotus and made particular note of the similarities between

Katherine Kepler, the astronomers mother, and ;iol2hilde, the fictional peddler of ma!ic

charms and herbs" <specially damnin! was the description of ;iol2hilde as a ,wise woman, in

lea!ue with celestial spirits, nor did Keplers 6oke about the >aemons preference for old

witches as travelin! companions help" #o make matters worse, Katherine Kepler was well

known for her vile temper and !enerally cantankerous disposition, not to mention the fact that

the aunt who had cared for her as a child was burned at the stake as a witch" #he sta!e was

set, char!es were leveled, and in 161/ Katherine Kepler was arrested on suspicion of

practicin! witchcraft" In his attempt to evade the scorn of the ?ristotelians by concealin! his

pro5)opernican work in the !uise of classical mytholo!y, Kepler had inadvertently set a trap

for himself and his mother, for they had become the unwittin! victims of the seventeenth5

century <uropean witch5craEe"

Johannes Keplers reputation as a noted mathematician5astronomer by no means served as a

!uarantee that Katherine Kepler would escape the fate of thousands of others who had already

died at the stake for their alle!ed complicity in what authorities envisioned as a mass satanic

conspiracy" Kepler was well aware of the seriousness of the char!es and he put all else aside

to work for Katherines e2oneration" ? lon!, tedious, and ta2in! le!al battle resulted+ only

after five years, part of which his mother spent in prison, was the old woman releasedC but the

dama!e had been done" Katherine Kepler died in ?pril of 16== from causes directly

attributable to the ri!ors of her imprisonmentC her son had been able to do little si!nificant

work while tryin! to obtain his mothers releaseC and the publication of the Somnium, at least

for the present, was out of the *uestion" -istorical circumstances, as durin! his student days at

#$bin!en in 1/03, had a!ain deprived Kepler of the opportunity to publicly air his views"

%nder these conditions, could it have truly mattered to Kepler whether or not his desire to

speak out had been thwarted by a narrow5minded faculty senate impervious to all scientific

in*uiry deemed anti5?ristotelian, or a !roup of superstitious and half5craEed witch5hunters

who had mistaken fantasy for reality.

#he tra!edy of Katherine Keplers lon! and painful ordeal wei!hed heavily upon her son for

the remainder of his life" -e felt a deep sense of personal responsibility for the old womans

demise even thou!h any reasonably ob6ective observer could find no !rounds for culpability

on his part" #here was little left for Kepler but his work, and he set out to complete a number

of pro6ects postponed by his mothers arrest and imprisonment" 8f primary concern was a

handbook of )opernican astronomy without which fellow scientists would not know how to

correlate the laws Kepler derived from #ychos observations with the work of )opernicus to

arrive at an operable model of the heliocentric system"

=3

?nother pro6ect of importance was

the planetary position predictions that would confirm the validity of Keplers theory of

elliptical orbits as set forth in the law of 163/" 8nly after overcomin! several ma6or obstacles,

which bio!rapher ?rthur Koestler likens to the #en 'la!ues of <!ypt, were the Rudolphine

Tables, named in honor of Keplers deceased patron, brou!ht to press"

=1

1eanwhile, Kepler returned to the manuscript of the ill5fated Somnium which had been

ne!lected since 1613" >urin! the last decade of his life, from 16=3 to 1633, Kepler wrote the

==3 footnotes to the >ream which are much lon!er than the te2t itself" It is within these

footnotes that the true scientist stands forth, for they contain the scientific core of the lunar

!eo!raphy" #his, the third and last sta!e of composition, was undertaken as a result of

Keplers dissatisfaction with his scant attention to scientific detail in the earlier version of the

manuscript" #he point is made by Kepler himself in a letter written to his friend, 1atthias

4erne!!er, dated >ecember 4, 16=3+

#wo years a!o, immediately after my return to inE I have started to work a!ain on the astronomy of

the moon, or rather to elucidate it by remarks"""" #here are 6ust as many problems as lines in my

writin!, which can only be solved astronomically, physically, or historically" 4ut what can one do

about this. #he people wish that this kind of fun, as they say, would throw itself around their neck,

with coEy armsC in playin! they do not wish to wrinkle their foreheads" #herefore, I decided to solve

the problem myself, in notes ordered and numbered"

==

'erhaps because of his mothers ordeal, coupled with the risin! popularity of the new

astronomy, Kepler no lon!er feared or even cared about the possible conse*uences of

publishin! a work founded on )opernican principles" #he insecurity that had resulted from

Keplers lifelon! fear of ?ristotelian sanctions a!ainst his work had finally been overcome"

-e had paid a price that few men of his or any other !eneration are willin! to pay, and then,

6ust before the manuscript could be published, death une2pectedly deprived him of the

satisfaction of seein! his lon! labor in print"

In his analysis of the Somnium Keplers bio!rapher 1a2 )aspar muses over the *uestion+

@hat would the >ream have been like had Kepler written about a ,moon state, the way his

contemporary, )ampanella, composed a ,sun state ,.

=3

#he *uestion arose at Keplers own

su!!estion in the same letter to 4erne!!er in which he had outlined his reasons for addin!

footnotes to the Somnium" Kepler asks+

)ampanella wrote a City o the Sun" @hat about my writin! a ,)ity of the 1oon,. @ould it not be

e2cellent to describe the cyclopic mores of our time in vivid colors, but in doin! so7to be on the safe

side7to leave this earth and !o to the moon. 1ore in his !topia and <rasmus in his "raise o Folly

ran into trouble and had to defend themselves" #herefore let us leave the vicissitudes of politics alone

and let us remain in the pleasant, fresh !reen fields of philosophy"

=4

)aspar considers it unfortunate that Kepler did not carry out his planC but it is a view this

writer does not share"

=/

(o one, of course, can know the type of lunar society Kepler mi!ht

have created had he not wanted to stay out of the sticky realm of social and political

speculation+ he was a !enius and of all human *ualities none is more unpredictable" Atill, it is

difficult to believe that any work of social criticism he mi!ht have authored could have

matched Keplers contribution either to scientific theory or the new literary !enre, science

fiction" #here is little in the historical record to show that he possessed the political insi!ht of

either a Air #homas 1ore or an <rasmus, but everythin! to show that he was a scientific

!enius with few peers" #o have turned the Somnium into a polemic for social and political

reform would have almost certainly detracted from its real value as a uni*ue contribution to

science fiction and mi!ht have ne!ated its value in the field of scientific theory as well"

Keplers other ma6or bio!rapher, ?rthur Koestler, paints the picture of a man astride the crest

of a !reat ,watershed, in @estern intellectual history+ on the one side is the medieval world

where science is dominated by reli!ion and the teachin!s of the ancient &reeksC on the other

side is the modern world in which science finally becomes a discipline unto itself" Kepler

leans one way, then the otherC but he can never *uite e2tricate himself from the medieval

mentality of the times and cross over onto the plain of modern thou!ht" In many ways it is a

fair characteriEation, but one that fails to take sufficient account of the one work that

preoccupied Kepler off and on for some thirty5seven years and reflects the various sta!es in

his intellectual maturation as a scientist"

#he Somnium is itself a watershed, for it marks both the end of an old era and the be!innin!

of a new one" ?fter his introductory tribute to the classicists, the modern scientist takes

command" #he >aemon of avania is nothin! less than Keplers own subtly masked voice

speakin! with confidence and authority about the unlimited possibilities that he, believes

science holds for mankind" &one is the fantasy5utopian world of ucian and )ampanellaC in

its place is an ima!inative modern work anchored in fact and rich in rational scientific theory"

If Keplers little fictional work was to be overlooked by historians of science for over three

and one5half centuries, later writers of cosmic voya!es in the seventeenth, ei!hteenth, and

nineteenth centuries did not make the same mistake" #he Somnium was known to Jules Ferne,

-"&" @ells and, I believe, at least indirectly, to such contemporary writers of science fiction

as ?rthur )" )larke" Kepler opened the way for a new vision of the universe as the home of a

plurality of worlds"

=6

Aeen from the perspective of the twentieth century, there is no reason to

dispute the assertion that Keplers >ream is the ons et origo of modern science fiction"

=:

;ortunately, even after the passa!e of three hundred and fifty years, history has a way of

correctin! in6ustice and apportionin! credit where it is due" It has not been until the last few

years that Keplers many works have finally been !iven the attention merited by their ma6or

contributions to later scientific and technolo!ical developments, not the least of which are

twentieth5century mans lunar voya!es"

(8#<A

1" 1a2 )aspar, #epler, trans" and ed" )" >oris -ellman Gondon and (ew Dork 10/0H, pp" 4:549" #he full title

of Keplers work is Somnium seu Astronomia $unari %Dream or Astronomy o the Moon&'

=" ewis 1umford, The Myth o the Machine( The "entagon o "o)er G(ew Dork 10:3H, p" 46"

3" ?rthur Koestler, The Sleep)al*ers Gondon and (ew Dork 10/0H, p" ==9"

4" )aspar, #epler, p" 46"

/" ibid", p" 46"

6" ;or an e2cellent analysis of the Mysterium see Koestler, The Sleep)al*ers, pp" =4:5=6:"

:" #ycho could not *uite brin! himself to a full embrace of the )opernican system" -e accepted the concept of

heliocentrism but retained part of the ?ristotelian5'tolemaic system by theoriEin! that the planets circle the earth

which in turn circles the sun"

9" )aspar, #epler, p" 3/1" 8ne of the new twentieth5century scholars of the Somnium, 1ar6orie -ope (icolson,

shares the view that much of the work was written in the summer of 1630" -owever, 'rofessor (icolson writes,

,there are details which could not possibly have been known to Kepler before the sprin! of 1613", Ahe is

referrin! to &alileos publication of The Starry Messenger which made known detailed observations of the lunar

surface with the telescope" It is a point worth keepin! in mind, but one which does not si!nificantly alter the

historical account" Aee her article ,Kepler, the Somnium, and John >onne,, in Roots o Scientiic Thought, ed" by

'hilip '" @iener and ?aron (oland G(ew Dork 10/:H, p" 313"

0" #ranslation of the Somnium into <n!lish was first undertaken by Joseph Keith ane, a candidate for the

1aster of ?rts de!ree at )olumbia %niversity in 104:" #he thesis has not been published" #he first complete

published translation in <n!lish appeared in 106/+ #epler+s Dream trans" by 'atricia ;rueh Kirkwood with an

interpretation by John ear G4erkeley and os ?n!elesH" ? subse*uent translation appeared in 106:+ #epler+s

Somnium, trans" with a commentary by <dward Bosen G1adison and ondonH" %nless otherwise noted, I have

employed the Bosen translation when *uotin! from the Somnium"

13" #he reader may have already surmised that there is a substantial amount of autobio!raphical material in the

Somnium" ;or e2ample, Keplers father disappeared before his son formed any permanent impression of himC his

mother was a collector of herbsC and Kepler was 4rahes pupil, althou!h not at #ychos %ranibur! observatory

on -veen, but in 'ra!ue"

11" ear and Kirkwood, #epler+s Dream, pp" 4=I43"

1=" Ibid", p" 4/"

13" Aee (icolson, ,Kepler, the Somnium and John >onne,, pp" 3==I3=3"

14" Kepler anticipated the universal law of !ravitation later formulated by Air Isaac (ewton, but he lacked both

the mathematical proof and the ob6ectivity necessary to advance beyond the realm of speculation" Aee Koestler,

The ,atershed, pp" 336I343 and Bosen, #epler+s Somnium, pp" =19I==1"

1/" ear and Kirkwood, #epler+s Dream, p" /:"

16" Keplers ft" 6="

1:" Aee Keplers ft" 90 and 03"

19" 1ar6orie -ope (icolson, Voyages to the Moon G(ew Dork 1049H, p" 4:"

10" ibid", p" 44"

=3" #he work is titled the -pitome Astronomiae Copernicane, a somewhat misleadin! rubric for the <pitome is a

te2tbook of the Keplerian system rather than the )opernican system" Koestler, The Sleep)al*ers, p" 436"

=1" ;or an account of the difficulties encountered by Kepler see Koestler, pp" 4365411"

==" )arola 4aum!ardt" .ohannes #epler( $ie and $etters with an introduction by ?lbert <instein G(ew Dork

10/1H, p" 1//"

=3" )aspar, #epler, p" 3/1"

=4" 4aum!ardt, Johannes #epler( $ie and $etters, pp" 1//51/6"

=/" )aspar, #epler, p" 3/1"

=6" It mi!ht be ar!ued that this distinction belon!s to the Italian philosopher &iordano 4runo G1/4951633H whose

pantheistic teachin! encompassed a plurality of worlds distributed throu!hout an infinite universe" 4runo,

however, was a reli!ious mystic who soared into the metaphysical realm unencumbered by the ballast of

scientific thinkin! which was Keplers constant companion"

=:" (icolson, Voyages to the Moon, p" 41"

?4A#B?)#

;ollowin! an account of the painful family circumstances and risks attendin! the posthumous publication of

Somnium in 1634, this essay contends that the work marks the be!innin! of a new era" ?fter an initial tribute to

the classicists, the modern scientist takes over" #he >aemon of avania is nothin! less than Keplers own subtly

masked voice, speakin! with authority about the unlimited possibilities of science" &one is the fantasy5utopian

world of ucian and )ampanellaC in its place is an ima!inative modern work anchored in fact and rich in rational

scientific theory" ?nd if Keplers small5scaled fictional work was overlooked by historians of science for over

3/3 years, writers of cosmic voya!es durin! the seventeenth, ei!hteenth, and nineteenth centuries did not make

the same mistake" #he Somnium was known to Jules Ferne, -" &" @ells, and, I believe, to such contemporary

writers as ?rthur )" )larke" Kepler opened the way for a new vision of the universe as a home to a plurality of

worldsC indeed, Keplers Dream may be seen as the ons et origo of modern science fiction" 8nly in the last few

years have Keplers writin!s finally been !iven the attention merited by their historical importance and their

contribution to later scientific and technolo!ical developments, includin! twentieth5century mans lunar voya!es"

.ne of the #ost i#portant boo+s in the history of science' Kepler)s lon$/o(erloo+ed 0o#niu# #ade a

si$nificant contribution to the study of astrono#y! "ts uni1ue twofold nature' co#binin$ a serious scientific

treatise on lunar astrono#y with a fictional narrati(e about a trip to the #oon pu22led se(enteenth/century

readers as well as succeedin$ $enerations' and the wor+ lapsed into obscurity!

The 0o#niu# be$ins li+e a classical le$end and relates the author3s )drea#) about the ad(entures of a

youn$ #an' 4uracotus' a nati(e of an island called Thule by the ancients' "celand by se(enteenth/century

&uropeans! 4uracotus3 father' a fisher#an by trade' died at the e,tre#ely ad(anced a$e of 150' but the

child was still too youn$ to ha(e any recollection of hi#! 6iol,hilde' the #other' is a )wise wo#an') who

supports both her son and herself by $atherin$ herbs which are then coo+ed' stuffed in little ba$s of

$oats+in' and sold at a nearby port to sailors! The ba$s supposedly harbor #ysterious luc+y char#s and the

healin$ powers re1uired by sea#en on the lon$ and always dan$erous (oya$es across the north 7tlantic!

.ne day' out of curiosity 4uracotus cut open one of the ba$s his #other intended to sell to a ship3s captain'

scatterin$ its contents on the $round! "n a fit of an$er 6iol,hilde3s te#per $ot the best of her and she sold

her son to the captain in place of the lost herbs!

The followin$ day' the captain set sail for *orway but he stopped in 4en#ar+ to deli(er a letter fro# a

bishop in "celand to the astrono#er Tycho Brahe' who then resided on the island of 8(een in the 0und

between %openha$en and &lsinore %astle! 4uracotus beca#e 1uite ill durin$ the (oya$e' apparently he

carried no ba$ of his #other3s char#s' and he was put ashore when Tycho3s letter was deli(ered! The

astrono#er 1uestioned the boy at so#e len$th' considered hi# to be 1uite intelli$ent' and undertoo+ to train

hi# in the science of astrono#y! 4uracotus3 response is enthusiastic9 :" was deli$hted beyond #easure by

the astrono#ical acti(ities' for Brahe and his students watched the #oon and the stars all ni$ht with

#ar(elous instru#ents!

7fter spendin$ fi(e years in Tycho3s co#pany 4uracotus too+ his #aster3s lea(e and sailed for ho#e! 8e

found 6iol,hilde #uch as she was when he left' e,cept that the old wo#an had suffered terribly as a result

of her i#petuosity and was o(er;oyed to see her son ali(e and well! 7 nu#ber of lon$ discussions ensued

durin$ which 6iol,hilde e,pressed happiness o(er 4uracotus3 ac1uaintance with the new science of the

stars! 0he confesses to her own special +nowled$e of the hea(ens and the fact that her teacher is none

other than the :4ae#on of La(ania:<the spirit of the #oon! :ost of the thin$s which you saw with your

own eyes or learned by hearsay or absorbed fro# boo+s' he related to #e as you did!: The #other then

re(eals her ulti#ate secret9 it is possible' with the assistance of the 4ae#on' to tra(el to La(ania and' 1uite

predictably' she as+s her son to acco#pany her on ;ust such a lunar (oya$e! 4uracotus consents and :as

soon as the sun set below the hori2on' and was in con;unction with the planet 0aturn in the si$n of the Bull'

6iol,hilde su##oned the 4ae#on and seated herself ne,t to her son who co(ered their heads with a

blan+et! =ithin a few #o#ents the ;ourney of )fifty thousand >er#an #iles) had be$un' up throu$h the

ethereal re$ions to the #oon!

7 second' and #ore i#portant source of inspiration for Kepler3s #oon (oya$e was ?lutarch3s The 6ace on

the oon' which Kepler read in 15@5! "t is a sy#posiu# of >ree+ scientific thou$ht that includes the (iews

of 8ipparchus' 7ristotle' and 7ristarchus of 0a#os! &,tensi(e speculation on the lunar en(iron#ent as a

possible ho#e for life is presentedA and ?lutarch e(en relates the story of a #ythical tra(eler<a >ree+

4uracotus<who sails to an island whose residents ha(e +nowled$e of the passa$e to the #oon!12 Kepler

now had the classical precedent he lac+ed durin$ his student days9 he e(en hoped to publish translations

both of Lucian3s and ?lutarch3s wor+ with the 0o#niu# to show his debt to these classical writers' and

hopefully blunt potential criticis# of his own #oon (oya$e!13 "t was a tas+ he did not co#plete!

=hile Kepler3s #ethod of fli$ht to the #oon is not #ar+edly different fro# that outlined by Lucian' and

althou$h #uch of his inspiration for lunar e,ploration is undeniably ?lutarchian' the 0o#niu# represents a

sharp brea+ with classical traditionA the first inti#ation of which occurs durin$ the (oya$e itself! =e are

infor#ed that the fli$ht of four hours is #ost difficult and frau$ht with the $reatest dan$er to life! .nly those

who are slender of body are acceptable' thus rulin$ out #ost >er#an #ales whose $eneral corpulence was

apparently distasteful to the slender Kepler! "n ;est Kepler carried the #atter further by pointin$ out the

4ae#on3s preference for Bdried/up old wo#en' e,perienced fro# an early a$e in ridin$ he/$oats at ni$ht or

for+ed stic+s or threadbare cloa+s!C "t was to pro(e a #ost costly ;o+e for' as we shall see' it later bac+fired

on its author whose own #other was accused of practicin$ witchcraft by superstitious nei$hbors and nearly

burned at the sta+e by the authorities!

The ta+e/off for the #oon hits the tra(eler as a se(ere shoc+' Bfor he is hurled ;ust as thou$h he had been

shot aloft by $unpowder to sail o(er #ountains and seas!C "n order to counteract what "saac *ewton would

later define as the force of $ra(ity' the #oon (oya$ers are put to sleep with the aid of opiates and their

li#bs are arran$ed in such a way that their bodies will not be torn apart by the force of acceleration!1-

0ince breathin$ is inhibited by the swift passa$e of e,tre#ely cold air throu$h the nostrils' da#p spon$es

are applied to the face! =ithin a short ti#e the speed of fli$ht beco#es so $reat that the body in(oluntarily

rolls itself up into a ball li+e an endan$ered spider and we are carried alon$ al#ost entirely by our will alone'

so that finally the bodily #ass proceeds toward its destination of its own accord! Kepler had introduced the

concept of inertia to the physical sciences and had e,tended its operation into the hea(ens!

Kepler anticipates another #a;or obstacle to the #oon (oya$er when he obser(es that we a$reed not to

be$in Buntil the #oon be$ins to be eclipsed on its eastern side! 0hould it re$ain its full li$ht while we are still

in transit' our departure beco#es futile!C "n other words' Kepler +new that once outside the protecti(e

blan+et pro(ided by the earth3s at#osphere' hu#ans could not sur(i(e the resultin$ solar bo#bard#ent9 the

fli$ht #ust be$in at the critical #o#ent when the sun is behind the earth or at a point directly opposite the

point of ta+e/off! 4urin$ a lunar eclipse the earth3s shadow would pro(ide the tunnel of dar+ness re1uired to

protect the (ulnerable #oon (oya$erA and it is not by accident that the #a,i#u# duration of such an eclipse

is four and one/half hours' ;ust one/half hour #ore than the duration of the (oya$e itself!15 7 further

indication of Kepler3s #astery of %opernican astrono#y is his understandin$ that since the earth and the

#oon are both in #otion' the shortest route to the latter would not be the strai$ht line ad(ocated by such

ancient writers of #ytholo$y as Lucian' but a tra;ectory fro# earth to a point in space where the #oon and

the lunar (oya$ers would arri(e si#ultaneously!16

B%a#panella wrote a %ity of the 0un! =hat about #y writin$ a )%ity of the oonD) =ould it not be e,cellent

to describe the cyclopic #ores of our ti#e in (i(id colors' but in doin$ so<to be on the safe side<to lea(e

this &arth and $o to the oonDC E Johannes Kepler!

Kepler)s #odel to e,plain the relati(e distances of the planets fro# the 0un in the %opernican 0yste#!

6ollowin$ an account of the painful fa#ily circu#stances and ris+s attendin$ the posthu#ous publication of

0o#niu# in 163-' this essay contends that the wor+ #ar+s the be$innin$ of a new era! 7fter an initial

tribute to the classicists' the #odern scientist ta+es o(er! The 4ae#on of La(ania is nothin$ less than

Kepler3s own subtly #as+ed (oice' spea+in$ with authority about the unli#ited possibilities of science! >one

is the fantasy/utopian world of Lucian and %a#panellaA in its place is an i#a$inati(e #odern wor+ anchored

in fact and rich in rational scientific theory!

7nd if Kepler3s s#all/scaled fictional wor+ was o(erloo+ed by historians of science for o(er 350 years'

writers of cos#ic (oya$es durin$ the se(enteenth' ei$hteenth' and nineteenth centuries did not #a+e the

sa#e #ista+e! The 0o#niu# was +nown to Jules Ferne' 8! >! =ells' and' " belie(e' to such conte#porary

writers as 7rthur %! %lar+e! Kepler opened the way for a new (ision of the uni(erse as a ho#e to a plurality

of worldsA indeed' Kepler3s 4rea# #ay be seen as the )fons et ori$o) of #odern science fiction!

sources9 depauw!edu' do(erpublications!co#' depauw!edu

C lo$ in or si$n up to post co##ents

Berttelsernas mnresor

>en fJrsta historien om att resa till mKnen

Den frsta modrna mnfrdshistorien som fick ngon betydelse skres !"#$ a

fransmannen Jules Verne% den hette &De la 'erre ( la )*ne& +Frn ,orden till -nen.

Fortsttningen% &/*to*r de la )*ne&+R*nt -nen. kom !"0!1

2erne ar inte den enda som satt och plitade p historier om resor i rymden *nder

!"#34talet% men det ar 2ernes berttelser som direkt inspirerade flera a frsta

generationens rymdfartsteoretiker1

Som litterr genre fanns mnresor med lngt fre 2ernes tid% men h*r lngt fre5

6w =9"/ 1009, uppdat" 39"1="=33/

>e allra fJrsta mKn5historierna kunde inte skrivas fJrrLn myter och !udaberLttelser hade fKtt

vika fJr rationella fJrsJk att med iaktta!elser och mLtnin!ar skapa en vLrldsbild"

;Jr forntidens mLnniska var den 6ord hon vandrade pK en platt skiva med himlavalvet la!d

som en snurrande ostkupa Jver" I -omerosM Iliad beskrivs 6orden pK 5 och som 5 den

praktskJld smed5!uden -efaistos !Jr Kt ?chilleus" I 8dysseen rKkar ,den mKn!fJrsla!ne

8dysseus, ut fJr alla tLnkbara Lventyr" <n resa till mKnen Lr otLnkbar, och fJrekommer inte"

1Knen nLmns inte ens"

%nder senantiken lyckades Aristarchos r/n Samos Gca"313 5 =33 f"KrH nKn!Kn! krin! =63

fJre vKr tiderLknin!s bJr6an, anvLnda e!na mLtnin!ar och <uklides dK helt nya !eometri5

sammanstLllnin! till h6Llp fJr att bestLmma de relativa avstKnden mellan 6orden, mKnen och

solen"

?ristarchos kom till att strLckan solen5mKnen var Jver 19 men under =3 !Kn!er strLckan

mKnen56orden, med lednin! av 6ordsku!!ans form vidmKnfJrmJrkelser, att mKndiametern

mKste vara dry!t 1N3 av 6ordens" 1KnavstKndet fick han till krin! 93 6ordradier" Aolens

diameter fick han till : !Kn!er 6ordens, och solens volym fJl6aktli!en 3435faldi!t 6ordens

volym"

>en lo!iska slutsatsen var att 6orden omJ6li!en kunde vara vLrldsalltets centrum" >et var

fJrsta !Kn!en i historien som en m0tning hade uppda!at nK!ot om vLrldsalltets by!!nadO

I ?le2andria bestLmde 1useion5fJrmannen -ratosthenes G=:/ 5 10/ f"KrH 6ordens diameter

till ett vLrde som vi ida! anser nK!orlunda rLtt, och dK kunde ocksK avstKndet till mKnen

beskrivas med landsvL!smKtt" 1Ktten visade klart att det mesta av vLrldsalltet mKste vara tom

rymd, med 6orden, solen och mKnen som mycket smK kroppar i den stora tomheten "

"lutarchos r/n Chaeronea G46 5 1=3H, av oss mest kLnd som levnadstecknare, skrev Lven

essLer" <n av dem handlar om det ansikte man ser i mKnen" 'lutarchos beskriver sin mKne

som en 6ord i miniatyr, men bebodd av ,daimones,, som via de broar sol5 och

mKnfJrmJrkelserna upprLttar kan besJka Jorden" Aokrates ,daimon, var en av dem, och

'lutarchos misstLnkte att oraklet i >elfi hade med mKn5demonerna att skaffa"

8ch nu Lr det da!s fJr de fJrsta bevarade mKnrese5historierna 163 e"Kr"

$u*ianos r/n Samosata Gca"11/5=33H anvLnde !ladeli!en, 43 Kr efter 'lutarchos frKnfLlle,

mKnen som en lokal fJr nK!ra av sina satiriska berLttelser" I ,Alethes 1istoria, G<n sann

berLttelseH sveper en s6uttionio dy!ns storm utanfJr -erakles stoder ivL! berLttelsens ,6a!,

med skepp, besLttnin! och allt till mKnen" >et Kttionde dy!net klarnar vLdret och 2vi ic* ett

stort land i luten i si*te3 li*t en s*imrande 4'2

Nicolaus Copernicus G14:3 5 1/43H, .ohannes #epler G1/:151633H och 5alileo 5alilei G1/64

5 164=H to! upp och fJrnyade ?ristarchosM heliocentriska vLrldsmodell" &alilei och Kepler

kunde efter 1630 dessutom betrakta mKnen !enom de fJrsta teleskopen"

&alileo &alileis brevvLn, doctor mathematicus Johannes Kepler, var den, som konstruerade

prototypen till det e!entli!a astronomiska teleskopet 5 det som &alilei anvLnde var en urtyp

fJr teaterkikare" Kepler var ocksK den fJrste som Jversatte ukianosM ,Alethes 1istoria, till

latin" Kepler skrev dLrtill en e!en mKnrese5historia ,Somnium2 G>rJmmenH var den fJrsta och

bLsta bland de nya mKnrese5berLttelserna som teleskoptittandet lockade fram"

Kepler plitade pK Aomnium fJr sitt hJ!a nJ6es skull, av och till, under mer Ln ett

decennium" Aomnium trycktes fJrst efter hans dJd, pK latin Kr 163= och pK tyska 1634"

Kepler visste att 6ordens atmosfLr inte strLcker si! Lnda till mKnen" 1en dK han inte kLnde

till nK!on fysisk mJ6li!het att ta si! dit, valde han som vehikel sin fantasi, som han fJrklLdde

till en drJm"

,"/ den s*imrande 4n $evania3 bel0gen p/ emtio tusen tys*a mils avst/nd i den d6upa

ethern23 dvs pK mKnen, bor, i enli!het med 'lutarchos, andevLsen, demoner, som kan fly!a

mellan 6orden och mKnen lLn!s den sku!!bro som uppstKr vid sol5 eller mKnfJrmJrkelser"

1an kan tillkalla dessa andar !enom att yttra t6u!o ma!iska bokstLver G?A#B8(81I?

)8'<B(I)?(?H, och om de Lr vLlvilli!t sinnade, kan de lKta en astronom fJl6a med pK en

resa Jver" ;Jrutsatt dK att astronomens tankevLrld inte Lr alltfJr 6ordbunden och astronomen

s6Llv inte fJr korpulent" 'ekfin!ret riktas mot Tycho 7rahe G1/4651631H, som visserli!en lLt

Kepler ta del av sitt superba observationsmaterial, men som sK lLn!e han levde lLt denne

betala fJr var6e smula med !yckel och hKn"

1Kn5demonerna skyr solens l6us i likhet med astronomerna" Kepler minns sin JlkLllare i

'ra!, ,varest man p/ b0sta s0tt observerar solens g/ng 4ver meridianen2'

Kepler konstaterar att strJmmande vatten forslar bort lJsmark frKn ber!en och breder ut det

Jver lK!land" -an tycker si! se tecken pK att detta mKste ha skett pK mKnen likavLl som pK

6orden" <n idPhistoriskt vikti! iaktta!else+ >en aristoteliska skillnaden mellan de evi!a

himlarna och fJr!Ln!elsens Jord e2isterar inte"

You might also like

- The Terminal Beach - J G BallardDocument225 pagesThe Terminal Beach - J G Ballardroughmagic2No ratings yet

- Bronowski - The Creative MindDocument9 pagesBronowski - The Creative Mindroderick_miller_3100% (1)

- Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, Fritz Saxl - Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in The History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, 1979Document268 pagesRaymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, Fritz Saxl - Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in The History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, 1979Zeleny100% (4)

- Saturn & Melancholy - Parte1Document70 pagesSaturn & Melancholy - Parte1luca1234567No ratings yet

- A Brieft History of Sci-FiDocument17 pagesA Brieft History of Sci-FiIcha SarahNo ratings yet

- Johannes Kepler - The DreamDocument31 pagesJohannes Kepler - The DreamCem AvciNo ratings yet

- Astrology in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Science of Omens and the Knowledge of the HeavensFrom EverandAstrology in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Science of Omens and the Knowledge of the HeavensRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- (1620) Somnium or The Dream - Johannes KeplerDocument18 pages(1620) Somnium or The Dream - Johannes KeplerSamurai_Chef100% (4)

- Kepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order Amid Religious War, Political Intrigue, and the Heresy Trial of His MotherFrom EverandKepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order Amid Religious War, Political Intrigue, and the Heresy Trial of His MotherRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (42)

- Keplar and AstrologyDocument16 pagesKeplar and Astrologyraghav VarmaNo ratings yet

- Copernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution BeganFrom EverandCopernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution BeganRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- A More Perfect Heaven: How Copernicus Revolutionized the CosmosFrom EverandA More Perfect Heaven: How Copernicus Revolutionized the CosmosRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (95)

- The Pursuit of Harmony: Kepler on Cosmos, Confession, and CommunityFrom EverandThe Pursuit of Harmony: Kepler on Cosmos, Confession, and CommunityNo ratings yet

- Immanuel Velikovsky PDFDocument8 pagesImmanuel Velikovsky PDFmika2k01100% (1)

- Nicolaus Copernicus: A Short Biography: The Astronomer Who Moved the EarthFrom EverandNicolaus Copernicus: A Short Biography: The Astronomer Who Moved the EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Story of Assyriology and Stars From 'Behind The Curtain' of Modern Science - Rumen KolevDocument16 pagesA Story of Assyriology and Stars From 'Behind The Curtain' of Modern Science - Rumen KolevAngela GibsonNo ratings yet

- Kepler's Dream: With the Full Text and Notes of Somnium, Sive Astronomia Lunaris, Joannis KepleriFrom EverandKepler's Dream: With the Full Text and Notes of Somnium, Sive Astronomia Lunaris, Joannis KepleriRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Formulary For A New UrbanismDocument5 pagesFormulary For A New UrbanismRobert E. HowardNo ratings yet

- Cosmos AlternativoDocument467 pagesCosmos AlternativoLeandro DiademiNo ratings yet

- Johannes Kepler-WPS OfficeDocument15 pagesJohannes Kepler-WPS OfficeMarlon Hernandez JrNo ratings yet

- The Composition of Kepler's Astronomia novaFrom EverandThe Composition of Kepler's Astronomia novaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Johannes KepplerDocument2 pagesJohannes KepplermakNo ratings yet

- A Brief Journey To The Kepler'S LifeDocument10 pagesA Brief Journey To The Kepler'S LifeIrvan PrakosoNo ratings yet

- Roger Bacon, Byname Doctor Mirabilis (Latin: "Wonderful Teacher"), (Born C. 1220Document4 pagesRoger Bacon, Byname Doctor Mirabilis (Latin: "Wonderful Teacher"), (Born C. 1220Allen Jay Fernandez AsignacionNo ratings yet

- Kepler and The Jesuits - Smaller FileDocument78 pagesKepler and The Jesuits - Smaller Filedanielsolow100% (2)

- γαλιλαιος κεπλερ PDFDocument10 pagesγαλιλαιος κεπλερ PDFmarkosNo ratings yet

- Galileo 1564-1642 and Kepler 1571-1630 The ModernDocument15 pagesGalileo 1564-1642 and Kepler 1571-1630 The ModernShivam Das, Tehsil KulpaharNo ratings yet

- 986213Document29 pages986213Mike SevekhNo ratings yet

- Nicolaus CopernicusDocument3 pagesNicolaus CopernicusDarlene Ramirez PeñaNo ratings yet

- Astronomia Nova Harmonices Mundi Epitome Astronomiae CopernicanaeDocument4 pagesAstronomia Nova Harmonices Mundi Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanaetrfghhh100% (1)

- (PE) (Andrew) Johannes Kepler 1571-1630Document2 pages(PE) (Andrew) Johannes Kepler 1571-1630jcb1961No ratings yet

- StsreviewerDocument15 pagesStsreviewerSy CervantesNo ratings yet

- Johannes KeplerDocument25 pagesJohannes KeplersigitNo ratings yet

- Johannes KEPLER Astronomical WorkDocument4 pagesJohannes KEPLER Astronomical WorkDivine Burlas AzarconNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7 The Scientific RevolutionDocument71 pagesLecture 7 The Scientific Revolutionkaijun.cheahNo ratings yet

- Name:: - Marie CurieDocument7 pagesName:: - Marie CurieLea Mae PerdonNo ratings yet

- Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck: (1858 - 1947) : Letters To Progress in PhysicsDocument4 pagesMax Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck: (1858 - 1947) : Letters To Progress in PhysicsCarlos Arias JiménezNo ratings yet

- Keplers SomniumDocument1 pageKeplers Somnium심소미No ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press The History of Science SocietyDocument7 pagesThe University of Chicago Press The History of Science Societyzoltán kádárNo ratings yet

- The Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler Review By: George Gaylord Simpson Isis, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Spring, 1966), Pp. 126-127 Published By: On Behalf of Stable URL: Accessed: 15/06/2014 21:27Document3 pagesThe Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler Review By: George Gaylord Simpson Isis, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Spring, 1966), Pp. 126-127 Published By: On Behalf of Stable URL: Accessed: 15/06/2014 21:27zoltán kádárNo ratings yet

- Copernicus Osiander and The Ad Lectorem - Setting The Stage For A New WorldDocument15 pagesCopernicus Osiander and The Ad Lectorem - Setting The Stage For A New Worldapi-346383243No ratings yet

- KEPLERDocument13 pagesKEPLERSambit Kumar BiswalNo ratings yet

- Pioneer of Galactic Astronomy: A Biography of Jacobus C. KapteynFrom EverandPioneer of Galactic Astronomy: A Biography of Jacobus C. KapteynNo ratings yet

- Roger Bacon Early LifeDocument1 pageRoger Bacon Early LifeEduardoNo ratings yet

- ASTR101 Unit 4 ReadingDocument13 pagesASTR101 Unit 4 ReadingDolamani MajhiNo ratings yet

- Copernicus BiographyDocument6 pagesCopernicus BiographyAlena JosephNo ratings yet