Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coeliac Disease PDF

Uploaded by

Vijay Rana0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 views6 pagescoeliac disease detail

Original Title

coeliac disease.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentcoeliac disease detail

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 views6 pagesCoeliac Disease PDF

Uploaded by

Vijay Ranacoeliac disease detail

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Coeliac Disease

Synonyms: gluten-sensitive enteropathy, celiac disease, celiac sprue

This is an immune-mediated, inflammatory systemic disorder provoked by gluten and related prolamines in

genetically susceptible individuals.

[1]

Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye and barley.

Genetics

It is a multigenetic disorder, associated with HLA types HLA-DQ2 (90%) or HLA-DQ8, plus other genetic or

environmental factors. HLA typing indicating lack of DQ2 or DQ8 has a high negative predictive value, which may

be useful if trying to exclude coeliac disease.

[2]

There is a familial tendency (10-15% of first-degree relatives will also be affected), and identical twins'

concordance is 70%. It is theoretically possible, by HLA testing, to provide more accurate information to parents

with a child with coeliac disease (CD) about the real risk for another child having the disease, including an

antenatal assessment.

[3]

Epidemiology

Prevalence is approximately 1 in 100 people in the UK.

[2]

Prospective birth cohort studies suggest 1% of children

have immunoglobulin A (IgA) endomysial antibodies by 7 years of age.

[4]

However, only 10-20% will have been

diagnosed as having coeliac disease (CD).

[5]

The disorder is thought to be rare in central Africa and East Asia.

[6]

Presentation

It may present at any age.

[1] [2]

Coeliac disease (CD) can be difficult to recognise because of the wide variation

in symptoms and signs. Many cases may be asymptomatic.

Babies and young children present any time after weaning (peak 9 months to 3 years):

Malabsorption generally presents with diarrhoea (frequent paler stools), weight loss and

failure to thrive.

Vomiting, anorexia, irritability and constipation are also common.

The abdomen may protrude, with eversion of the umbilicus.

Older children and adults may present with:

Anaemia (folate or iron deficiency).

Nonspecific symptoms of abdominal discomfort, arthralgia, anaemia, fatigue and malaise.

Diarrhoea, steatorrhoea and malabsorption.

Mouth ulcers and angular stomatitis are common (85% have asymptomatic iron/folate

deficiency, 15-30% have vitamin D deficiency and 10% vitamin K deficiency).

Deficiencies of vitamin E also occur.

B12 deficiency can also occur (mechanism unknown).

Some CD patients are identified at infertility clinics. CD is associated with subfertility in both men and

women, miscarriage, low-birthweight children and increased infant mortality.

[7]

Dermatitis herpetiformis is the classic skin manifestation of CD - almost all patients with the rash have either

detectable villous atrophy (approximately 75%) or minor mucosal changes. Lamellar ichthyosis has also been

reported in association with CD.

[8]

Page 1 of 6

Investigations

Specific auto-antibodies

CD-specific antibodies include auto-antibodies against tissue transglutaminase type 2 (tTGA2), including

endomysial antibodies (EMAs), and antibodies against deamidated forms of gliadin peptides (DGPs). These are

measured in blood.

IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTGAs) is the preferred investigation. EMAs are used if the

tTGA test is not available or equivocal. The tTGA is a newer test (tTGA is the auto-antigen of EMA) and

is gradually replacing the latter, but both are highly specific and sensitive for untreated CD, provided

the patient is still on gluten. tTGA should not be performed on children younger than 2 years.

[1]

False negatives occur if the patient has selective IgA deficiency, as occurs in approximately 0.4% of

the general population and in 2.6% of patients with CD (laboratories should test for IgA deficiency on

negative samples). Use IgG tTGA and/or IgG EMA serological tests for people with confirmed IgA

deficiency.

Antibodies frequently become undetectable after 6-12 months of a gluten-free diet (GFD) and thus can

be used to monitor the disease.

Positive antibodies should prompt a referral to a gastroenterologist. In children and adolescents with signs or

symptoms suggestive of CD and high anti-tTGA titres (levels 10 times the upper limit of normal), the likelihood

for villous atrophy is high. The paediatric gastroenterologist may discuss with the parents and patient (as

appropriate for age) the option of performing further laboratory testing (EMA, HLA) to make the diagnosis of CD

without biopsies.

Referral should also be made where the serology is negative, but there is strong clinical suspicion of CD.

HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 typing

A negative result for these makes a diagnosis of coeliac disease (CD) highly unlikely. If available, it can be offered

to:

Patients with an equivocal diagnosis of CD.

Asymptomatic patients - as a screening tool for, for example, first-degree relatives, patients with

Down's syndrome or known associated autoimmune or other conditions.

In the community for example, a GP may request HLA testing in a young patient with Down's syndrome, to

obviate the need for annual screening.

Biopsy confirmation

Patients will need to stay on gluten until after the biopsy. The biopsy is obtained by upper gastrointestinal

endoscopy or by suction capsule.

Histological examination of the mucosa classically shows 'subtotal villous atrophy' and results in

malabsorption - however, mucosa is of normal thickness, the villous atrophy is compensated by crypt

hyperplasia. There should be full clinical remission on excluding gluten from the diet.

Under these circumstances, tTGA or EMA antibodies found at the time of diagnosis and their

disappearance after gluten exclusion, means that it is only necessary to perform a further biopsy (and

even a further gluten challenge and more biopsies) if there are still doubts.

Other investigations

FBC shows anaemia in 50%; iron and folate deficiency are both common (microcytes and

macrocytes), hypersegmented leukocytes and Howell-Jolly bodies (splenic atrophy). Also check B12,

folate, ferritin, LFTs, calcium and albumin.

LFTs may show elevated transaminases which should return to normal on a GFD. If they don't,

consider associated autoimmune disease, ie primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis or primary

sclerosing cholangitis.

Small bowel barium studies are occasionally needed to exclude other causes of malabsorption and

diarrhoea, and to diagnose rare complications such as obstruction or lymphoma.

Page 2 of 6

Target case finding for serological testing

Consider the diagnosis and perform serological testing in all patients who present with:

[4]

Chronic or intermittent diarrhoea.

Failure to thrive or faltering growth in children (including short stature and delayed puberty).

[6]

Persistent or unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea and vomiting.

Prolonged fatigue ('tired all the time').

Recurrent abdominal pain, cramping or distension.

Sudden or unexpected weight loss.

Unexplained iron-deficiency anaemia, or other unspecified anaemia.

Also, offer testing to patients with known associated conditions:

[4]

Autoimmune thyroid disease.

Dermatitis herpetiformis.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

[9]

Type 1 diabetes (3-12% have coeliac disease (CD))

[6]

- screen children every 2-3 years until

adulthood, and subsequently if adults have a low body mass index (BMI) or develop unexplained

weight loss.

[1]

First-degree relative (parents, siblings or children) with CD.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) also suggests considering serological testing in

patients with:

[4]

Addison's disease, amenorrhoea, aphthous stomatitis (mouth ulcers), autoimmune liver

conditions, autoimmune myocarditis, chronic thrombocytopenia purpura, dental enamel defects, depression or

bipolar disorder, Down's syndrome, epilepsy, lymphoma, metabolic bone disease (such as rickets or

osteomalacia), microscopic colitis, persistent or unexplained constipation, persistently raised liver enzymes with

unknown cause, polyneuropathy, recurrent miscarriage, reduced bone mineral density and/or low-trauma

fracture, sarcoidosis, Sjgren's syndrome, Turner syndrome, unexplained alopecia and unexplained subfertility.

Differential diagnosis

IBS, lactose or other food intolerances, colitis (including inflammatory bowel disease), and other causes of

malabsorption.

Management

Starting a gluten-free diet (GFD) rapidly induces clinical improvement, which is mirrored by the mucosa. The diet

consists of no wheat, barley, rye, or any food containing them (eg bread, cake, pies).

[2]

Moderate quantities of

oats (free from other contaminating cereals) can be consumed, as studies suggest that they do not damage the

intestinal mucosa in most coeliac patients, although a small number of patients remain unwell if oats are included

in the diet. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines suggest oats be excluded at least for the first

year while patients get used to a GFD but then can be cautiously introduced. Rice, maize, soya, potatoes, sugar,

jam, syrup and treacle are all allowed. Gluten-free flour, bread and pasta are NHS prescribable. There is a gluten-

free food prescribing guide available for health professionals and Coeliac UK produces a prescribable product

list.

[10]

GPs are responsible for the appropriate prescription of gluten-free products.

Arrange a dietitian appointment (with regular reviews).

[2]

Even minor dietary lapses may cause recurrence. A

GFD should be lifelong, as relaxation of diet generally brings a return of symptoms and increased incidence of

complications. Add supplements as necessary (eg fibre, folic acid, iron, calcium and vitamin D). Serial tTGA or

EMA antibodies can be used to monitor response to diet.

Research is looking at how gluten could be detoxified in the intestine by oral endopeptidases. They are enzymes

that break the gluten peptides into small chunks with fewer adverse effects.

[6]

Follow-up

Patient compliance with a gluten-free diet (GFD) is poor, particularly in adolescents.

[6]

The long-term

Page 3 of 6

Patient compliance with a gluten-free diet (GFD) is poor, particularly in adolescents.

[6]

The long-term

health risks for patients who comply poorly with a GFD include nutritional deficiency and reduced bone

mineral density. About a quarter of patients with coeliac disease (CD) have osteoporosis of the lumbar

spine compared with 5% of matched controls. Bone mineral density improves significantly with a GFD.

Dietary compliance positively correlates with regular follow-up and knowledge of the condition.

Many coeliac patients have an inadequate energy intake. Poor absorption often leads to inadequate

intake of calcium and vitamin B6 and vitamin D.

Regular follow-up is an opportunity to provide patient-centred care that is sensitive to the individual's

life circumstances.

How often should patients be reviewed?

Patients should be followed up throughout their lifetime.

After diagnosis, the patient should be reviewed at the gastroenterology clinic after three months and

six months to ensure they are making satisfactory progress and managing the diet.

If well, they should be reviewed annually or sooner if problems arise - follow-up assessments are

currently being carried out by dietitians, nurses, general practitioners and gastroenterologists in

primary and secondary care.

The annual assessment

[2]

Disease status

General: weight, height, and BMI.

Symptom assessment: bowel function (stool frequency, stool consistency, blood in stool) abdominal

pain.

Investigations

FBC, LFTs, calcium and albumin, B12, folate, serum ferritin. Patients with coeliac disease (CD) who

adhere to a gluten-free diet (GFD) often eat inadequate intakes of folic acid and iron. Low

haemoglobin, red cell folate, and serum ferritin may suggest persisting malabsorption warranting

further assessment.

Antibody tests can be used to monitor significant dietary gluten ingestion.

Complication prevention

Osteoporosis risk assessment and management:

Consider measuring bone mineral density with a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)

scan at the time of diagnosis (depending on age), and the test should then be repeated:

After three years on a GFD (only if the baseline DEXA is abnormal).

[2]

At the menopause for all women.

At the age of 55 years for all men.

At any age if a fragility fracture is suspected (follow osteoporosis guidelines).

Calcium and/or vitamin D supplements can be prescribed if dietary intake is inadequate

(<1,500 mg/day) or the patient is housebound. Checking vitamin D levels and parathyroid

hormone levels may be appropriate in at-risk individuals.

[2]

Hyposplenism - some degree of splenic atrophy is present in most patients with CD, and is sufficiently

severe to cause peripheral blood changes in about a quarter (Howell-Jolly bodies, target cells and

elevated platelet count). Patients should be considered for:

Vaccination against pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae type b.

Vaccination against influenza.

Guidance about the increased risks attached to tropical infections, eg malaria.

Lifelong prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended.

Management of disease and associated medical problems

Discussion of familial risk if required. First-degree relatives of people with CD have a 1 in 10 chance of

developing the disease, and should be screened.

Page 4 of 6

Review prescription items - prescribing guidelines suggest minimum monthly prescription

requirements, so discuss prescribable items with any patients using fewer than these

recommendations.

Self-care:

Discuss GFD compliance and advice.

Discuss membership of the Coeliac Society.

Discuss use of the Coeliac Society's Gluten-free Food and Drink directory.

Provide dietary advice on weight, macronutrients, calcium, vitamin D, iron and fibre intake

as required.

Referral

You should consider specialist referral if:

There is poor response to a gluten-free diet (GFD).

There is weight loss on a GFD.

There is blood in stools.

There is onset of unexplained abdominal pain.

There are other clinical concerns.

Complications

Delayed diagnosis of coeliac disease (CD) may result in continuing ill health, osteoporosis, miscarriage and a

modest, increased risk of intestinal malignancy (in adults); also, growth failure, delayed puberty and dental

problems (in children).

[4]

Osteoporosis.

[11]

Cancer risk - there is conflicting research on this subject. Some research shows a small increase in

overall risks of developing malignancy, eg gastrointestinal cancers and some types of lymphoma.

[6]

Intestinal lymphoma usually presents with the return of bowel symptoms, although it usually responds

poorly to treatment.

Further reading & references

Guideline for the diagnosis and management of coeliac disease in children, British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Nutrition with Coeliac UK (Sept 2013)

Coeliac Disease; NICE CKS, May 2010

Karpati S; Dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2012 Jan;30(1):56-9. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.010.

1. Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease, European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and

Nutrition (January 2012)

2. The Management of Adults with Coeliac Disease; British Society of Gastroenterology (2010)

3. Bourgey M, Calcagno G, Tinto N, et al; HLArelated genetic risk for coeliac disease. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1054-9. Epub 2007

Mar 7.

4. Coeliac disease; NICE Clinical Guideline (May 2009)

5. Steele R; Diagnosis and management of coeliac disease in children. Postgrad Med J. 2011 Jan;87(1023):19-25. Epub

2010 Dec 3.

6. Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR; Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2009 Apr 25;373(9673):1480-93.

7. Pellicano R, Astegiano M, Bruno M, et al ; Women and celiac disease: association with unexplained infertility. Minerva Med.

2007 Jun;98(3):217-9.

8. Nenna R, D'Eufemia P, Celli M, et al; Celiac disease and lamellar ichthyosis. Case study analysis and review of the Acta

Dermatovenerol Croat. 2011 Dec;19(4):268-70.

9. Ford AC, Chey WD, Talley NJ, et al ; Yield of diagnostic tests for celiac disease in individuals with symptoms Arch Intern

Med. 2009 Apr 13;169(7):651-8.

10. Prescribable Product List, Coeliac UK

11. Guidelines for Osteoporosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Coeliac Disease, British Society of Gastroenterology

(2007)

Disclaimer: This article is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical

conditions. EMIS has used all reasonable care in compiling the information but make no warranty as to its

accuracy. Consult a doctor or other health care professional for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions.

For details see our conditions.

Page 5 of 6

Original Author:

Dr Huw Thomas

Current Version:

Dr Hayley Willacy

Peer Reviewer:

Dr Helen Huins

Last Checked:

13/06/2012

Document ID:

1975 (v25)

EMIS

View this article online at www.patient.co.uk/doctor/coeliac-disease-pro.

Discuss Coeliac Disease and find more trusted resources at www.patient.co.uk.

EMIS is a trading name of Egton Medical Information Systems Limited.

Page 6 of 6

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Engineering ConsultancyDocument30 pagesEngineering Consultancynaconnet100% (2)

- Spotify Strategig Possining and Product Life Cycle Four Basic Stages.Document5 pagesSpotify Strategig Possining and Product Life Cycle Four Basic Stages.Jorge YeshayahuNo ratings yet

- Fanuc 10t Parameter Manual PDFDocument1 pageFanuc 10t Parameter Manual PDFadil soukri0% (2)

- Chronic Pancreatitis: What Is The Pancreas?Document5 pagesChronic Pancreatitis: What Is The Pancreas?Vijay RanaNo ratings yet

- Changes To USMLE 2014-2015 Handout FINALDocument2 pagesChanges To USMLE 2014-2015 Handout FINALFadHil Zuhri LubisNo ratings yet

- Handling Questions Step by Step by Steven R. Daugherty, PH.D PDFDocument4 pagesHandling Questions Step by Step by Steven R. Daugherty, PH.D PDFYossef HammamNo ratings yet

- Dental:: 2. OPG - Dentigerous CystDocument56 pagesDental:: 2. OPG - Dentigerous CystVijay RanaNo ratings yet

- Final Surgery - OSCEDocument15 pagesFinal Surgery - OSCEVijay Rana50% (2)

- Q.1) A. B. C. D.: (Your Answer)Document11 pagesQ.1) A. B. C. D.: (Your Answer)Vijay RanaNo ratings yet

- Alien Cicatrix II (Part 02 of 03) - The CloningDocument4 pagesAlien Cicatrix II (Part 02 of 03) - The CloningC.O.M.A research -stopalienabduction-No ratings yet

- Academic 8 2.week Exercise Solutions PDFDocument8 pagesAcademic 8 2.week Exercise Solutions PDFAhmet KasabalıNo ratings yet

- Sir Rizwan Ghani AssignmentDocument5 pagesSir Rizwan Ghani AssignmentSara SyedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 NegotiationsDocument16 pagesChapter 15 NegotiationsAdil HayatNo ratings yet

- Beed 3a-Group 2 ResearchDocument65 pagesBeed 3a-Group 2 ResearchRose GilaNo ratings yet

- Past Simple (Regular/Irregular Verbs)Document8 pagesPast Simple (Regular/Irregular Verbs)Pavle PopovicNo ratings yet

- Whats New PDFDocument74 pagesWhats New PDFDe Raghu Veer KNo ratings yet

- SF3300Document2 pagesSF3300benoitNo ratings yet

- Share Cognitive Notes Doc-1Document15 pagesShare Cognitive Notes Doc-1GinniNo ratings yet

- b8c2 PDFDocument193 pagesb8c2 PDFRhIdho POetraNo ratings yet

- 17373.selected Works in Bioinformatics by Xuhua Xia PDFDocument190 pages17373.selected Works in Bioinformatics by Xuhua Xia PDFJesus M. RuizNo ratings yet

- Who Should Take Cholesterol-Lowering StatinsDocument6 pagesWho Should Take Cholesterol-Lowering StatinsStill RageNo ratings yet

- "Management of Change ": A PR Recommendation ForDocument60 pages"Management of Change ": A PR Recommendation ForNitin MehtaNo ratings yet

- Revised Market Making Agreement 31.03Document13 pagesRevised Market Making Agreement 31.03Bhavin SagarNo ratings yet

- 9702 s02 QP 1Document20 pages9702 s02 QP 1Yani AhmadNo ratings yet

- Dnyanadeep's IAS: UPSC Essay Series - 7Document2 pagesDnyanadeep's IAS: UPSC Essay Series - 7Rahul SinghNo ratings yet

- Study On SantalsDocument18 pagesStudy On SantalsJayita BitNo ratings yet

- Mcqmate Com Topic 333 Fundamentals of Ethics Set 1Document34 pagesMcqmate Com Topic 333 Fundamentals of Ethics Set 1Veena DeviNo ratings yet

- Audio Scripts B1 Student'S Book: CD 4 Track 38Document2 pagesAudio Scripts B1 Student'S Book: CD 4 Track 38Priscila De La Rosa0% (1)

- HDLSS Numerical Assignments - DOC FormatDocument3 pagesHDLSS Numerical Assignments - DOC FormatNikhil UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Victorian AOD Intake Tool Turning Point AuditDocument8 pagesVictorian AOD Intake Tool Turning Point AuditHarjotBrarNo ratings yet

- Approaching Checklist Final PDFDocument15 pagesApproaching Checklist Final PDFCohort Partnerships100% (1)

- LIFT OFF ModuleDocument28 pagesLIFT OFF ModulericardoNo ratings yet

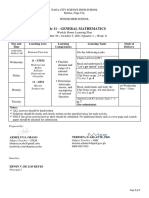

- General Mathematics - Module #3Document7 pagesGeneral Mathematics - Module #3Archie Artemis NoblezaNo ratings yet

- Movie Review TemplateDocument9 pagesMovie Review Templatehimanshu shuklaNo ratings yet

- Notes 1Document30 pagesNotes 1Antal TóthNo ratings yet

- Creative LeadershipDocument6 pagesCreative LeadershipRaffy Lacsina BerinaNo ratings yet