Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Economic Snapshot: May 2014

Uploaded by

Center for American Progress0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views6 pagesDespite a broken Congress, the president can still push progressive policies to help strengthen the middle class.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDespite a broken Congress, the president can still push progressive policies to help strengthen the middle class.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views6 pagesEconomic Snapshot: May 2014

Uploaded by

Center for American ProgressDespite a broken Congress, the president can still push progressive policies to help strengthen the middle class.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

1 Center for American Progress | Economic Snapshot: May 2014

Economic Snapshot: May 2014

Christian E. Weller on the State of the Economy

By Christian E. Weller and Jackie Odum May 28, 2014

Many middle-class families struggle with modest job growth, slow income growth, high

poverty, and a lack of employer-sponsored benefts, while corporate profts remain high.

Te United States needs to take action and adopt policies that create economic opportu-

nities for all to become fnancially secure. Progressive policies such as a higher minimum

wage, extended unemployment insurance benefts, and afordable health insurance can

contribute to stronger economic and job growth and lead to more and beter economic

opportunities for millions of middle-class Americans.

Te Afordable Care Act, or ACA, is just one example of good policy that promotes fnan-

cial growth and security for both middle-class families and our nations economy. Since its

enactment, the ACA has lowered projected budget defcits and provided Americans with

the fnancial security they need by expanding coverage, providing access to free preventive

care, and preventing insurance companies from charging women more than men.

Te president can continue to take some small steps toward progressive policies, despite

a dysfunctional Congress that is stymied by a radical conservative minority intent on

obstructing popular policies designed to help struggling American families. Such presi-

dential policies include creating beter jobs for low-wage workers in the federal govern-

ment and among government contractors, investing in job training and subsidies for

green energy, and promoting responsible contracting by encouraging pay transparency

and strengthening rules on employer retaliation.

1. Economic growth lags behind similar points in prior business cycles. Gross domes-

tic product, or GDP, slightly increased in the frst quarter of 2014 at an infation-

adjusted annual rate of 0.1 percent. Domestic consumption increased by an annual

rate of 3 percent, and housing spending substantially shrank by 5.7 percent, while

business investment growth fell at a rate of 2.1 percent. Exports decreased by 7.6

percent in the frst quarter, and government spending decreased by 0.5 percent.

1

Te

economy expanded by 11.1 percent from June 2009 to December 2013its slowest

expansion during recoveries of at least equal length.

2

Policymakers need to focus on

strengthening economic growth, e.g. by investing in infrastructure and education.

2 Center for American Progress | Economic Snapshot: May 2014

2. Improvements to U.S. competitiveness lag

behind previous business cycles. Productivity

growth, measured as the increase in infation-

adjusted output per hour, is key to increasing

living standards. U.S. productivity rose by 7.3

percent from June 2009 to December 2013, the

frst 18 quarters of the economic recovery since

the end of the Great Recession.

3

Tis compares

to an average of 11.9 percent during all previous

recoveries of at least equal length.

4

No previous

recovery had lower productivity growth than

the current one. Productivity growth is the main

driving force behind the countrys ability to raise

living standards. Weaker productivity growth

than in the past will make it harder to build a

strong middle class, requiring policymakers

atention to invest in U.S. competitiveness.

3. The housing market continues to recover

from historic lows. New-home sales amounted to an annual rate of 433,000 in April

2014a 4.2 percent decrease from the 452,000 homes sold in April 2013, and well

below the historical average of 698,000 homes sold before the Great Recession.

5

Te median new-home price in April 2014 was $275,800, up from one year earlier.

6

Existing-home sales were down by 7.5 percent in March 2014 from one year ear-

lier, but the median price for existing homes was up by 7.9 percent during the same

period.

7

Home sales have to go a lot further, given that homeownership in the United

States stood at 64.8 percent in the frst quarter of 2014, down from 68.2 percent

before the recession. Te current homeownership rates are similar to those recorded

in 1996, well before the most recent housing bubble started.

8

Although the housing-

market recovery started later than the wider economic recoveryand started out

at a record lowthe housing market has lately contributed a much-needed boost

to economic progress. As such, there is still plenty of room for the housing market

to provide more stimulation to the economy more broadly. Te fedgling housing

recovery could gain further strength if policymakers support economic growth and

job creation at the same time.

4. The outlook for budget deficits improves.Te nonpartisan Congressional Budget

Ofce, or CBO, estimated in April 2014 that the federal government will have a

defcitthe diference between taxes and spendingof 2.8 percent of GDP for fscal

year 2014, which runs from October 1, 2013, to September 30, 2014.

9

Tis defcit

projection is down from 4.1 percent in FY 2013.

10

Tis projected defcit for FY 2014

is slightly beter than what CBO predicted in February 2014, when it estimated a

defcit of 3 percent of GDP for FY 2014.

11

Te estimated defcit for FY 2014 is much

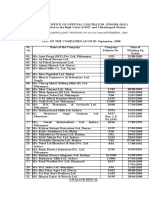

FIGURE 1

GDP growth in recovery in comparison

to previous recoveries

90

120

125

130

115

110

105

100

95

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

G

r

o

w

t

h

i

n

d

e

x

(

l

a

s

t

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

o

f

r

e

c

e

s

s

i

o

n

=

1

0

0

)

Mar 61

Mar 75

Dec 82

Mar 91

Dec 01

Jun 09

Number of quarters of economic recovery

Recovery after the Great Recession

Source: Authors calculations based on Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts

(U.S. Department of Commerce, 2014). Calculations only done for recoveries that have lasted at least four years.

3 Center for American Progress | Economic Snapshot: May 2014

FIGURE 2

Employment-to-population ratio

for 2554 year-olds, 19472014

smaller than it was in previous years due to a

number of measures that policymakers have

already taken to slow spending growth and raise

a litle more revenue than was expected just

last year. Te slowdown in health care costsa

result partially atributed to provisions within

the ACAhas signifcantly contributed to these

shrinking defcit projections.

12

Te improving

fscal outlook generates breathing room for poli-

cymakers to focus their atention on targeted,

efcient policies that promote long-term growth,

job creation, and defcit reduction.

5. Moderate labor-market recovery shows less

job growth than in previous business cycles.

Tere were 7.3 million more jobs in April 2014

than in June 2009. Te private sector added

8 million jobs during this period. Te loss of

some 601,000 state and local government jobs

explains the diference between the net gain of

all jobs and the private-sector gain in this period.

Budget cuts reduced the number of teachers,

bus drivers, frefghters, and police ofcers, among others.

13

Te total number of jobs

has now grown by 5.5 percent during this recovery, compared to an average of 12.7

percent during all prior recoveries of at least equal length.

14

Tose looking for jobs

still need assistance such as extended unemployment insurance benefts.

6. Employment opportunities grow very slowly for people in their prime earning

years. Te employed share of the population from ages 25 to 54which is unaf-

fected by the aging of the overall populationwas 76.5 percent in April 2014. Tis

was just above the level recorded in June 2009 and well below the levels recorded

since the mid-1980s and before the Great Recession started in 2007. Te employed

share of the population has, on average, grown by 3.6 percentage points at this stage

during previous recoveries of at least equal length.

15

Specifcally, there has been insuf-

fcient job growth to create real economic opportunities for people in the midst of

their main earning yearsyears when they need those opportunities the most.

7. Employer-sponsored benefits disappear. Te share of people with employer-spon-

sored health insurance dropped from 59.8 percent in 2007 to 54.9 percent in 2012,

the most recent year for which data are available.

16

Te share of private-sector workers

who participated in a retirement plan at work fell to 39.4 percent in 2012, down from

41.5 percent in 2007.

17

Families now have less economic security than in the past due

to fewer employment-based benefts, which requires them to have more private sav-

60%

80%

65%

70%

75%

85%

S

h

a

r

e

o

f

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

i

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

1

9

4

8

1

9

5

4

1

9

6

0

1

9

6

5

1

9

7

1

1

9

7

7

1

9

8

3

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

6

2

0

0

2

2

0

0

8

2

0

1

4

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (U.S. Department of Labor, 2014).

4 Center for American Progress | Economic Snapshot: May 2014

ings to make up the diference. Te ACA appears

to set a welcome counterpoint to the trend of

disappearing health insurance benefts. Since

the ACAs marketplace open enrollment period

began in October 2013, the uninsured rate has

dropped to 13.4 percent, the lowest monthly

rate recorded since 2008.

18

Moreover, uninsured

rates continue to decline among communities of

color and low-income Americans. Since January

2014, the uninsured rate has dropped by 7.1

percent for African Americans, 5.5 percent for

Hispanics, and 5.5 percent for lower-income

Americans.

19

8. Some communities continue to struggle

disproportionately from unemployment. Te

unemployment rate ticked down to 6.3 percent

in April 2014: Te African American unemploy-

ment rate was 11.6 percent; the Hispanic unem-

ployment rate was 7.3 percent; and the white unemployment rate was 5.3 percent.

Meanwhile, youth unemployment stood at 19.1 percent. Te unemployment rate for

people without a high school diploma ticked down to 8.9 percent, compared to 6.3

percent for those with a high school degree, 5.7 percent for those with some college

education, and 3.3 percent for those with a college degree.

20

Population groups with

higher unemployment rates have struggled disproportionately more amid the weak

labor market than white workers, older workers, and workers with more education.

9. The rich continue to pull away from most Americans. Incomes of households in the

95th percentilethose with incomes of $191,000 in 2012, the most recent year for

which data are availablewere more than nine times the incomes of households in

the 20th percentile, whose incomes were $20,599. Tis is the largest gap between the

top 5 percent and the botom 20 percent of households since the U.S. Census Bureau

started keeping records in 1967. Median infation-adjusted household income stood

at $51,017 in 2012, its lowest level in infation-adjusted dollars since 1995. And the

poverty rate remains highat 15 percent in 2012as the economic slump continues

to take a massive toll on the most vulnerable citizens.

21

10. Corporate profits stay elevated near pre-crisis peaks. Infation-adjusted corporate

profts were 88 percent larger in December 2013 than in June 2009. Te afer-tax

corporate-proft rateprofts to total assetsstood at 3.2 percent in December

2013, nearing the previous peak afer-tax proft rate of 3.3 percent that occurred

prior to the Great Recession.

22

Corporate profts recovered quickly during the eco-

nomic recovery, highlighting the bifurcated nature of the economy.

FIGURE 3

U.S. poverty rate, 2007 to 2012

54%

56%

58%

55%

57%

59%

60%

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

59.8%

58.9%

56.1%

55.3%

55.1%

54.9%

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (U.S. Department of Labor, 2014).

5 Center for American Progress | Economic Snapshot: May 2014

11. Corporations spend much of their money to keep shareholders happy. From

December 2007when the Great Recession startedto December 2013, nonf-

nancial corporations spent, on average, 98 percent of their afer-tax profts on divi-

dend payouts and share repurchases.

23

In short, almost all of nonfnancial corporate

afer-tax profts went to keep shareholders happy during the current business cycle.

Nonfnancial corporations also held, on average, 5.4 percent of all of their assets in

cashthe highest average share since the business cycle that ended in December

1969. Nonfnancial corporations spent, on average, 168 percent of their afer-tax

profts on capital expenditures or investmentsby selling other assets and by bor-

rowing. Tis was the lowest ratio since the business cycle that ended in 1960. U.S.

corporations have prioritized keeping shareholders happy and building up cash over

investments in structures and equipment.

12. Poverty is still widespread. Te poverty rate remained fat at 15 percent in 2012

the most recent year for which data are availablewhich is an increase of 0.7 per-

centage points over the three years of the recovery from 2009 to 2012. Te poverty

rate has fallen on average by 0.7 percentage points in previous recoveries of at least

equal length. Moreover, some population groups sufer from much higher poverty

rate than others. Te African American poverty rate, for instance, was 27.2 percent

and the Hispanic poverty rate was 25.6 percent, while the white poverty rate was 9.7

percent. Te poverty rate for children under age 18 stood at 21.8 percent. More than

one-third of African American children37.9 percentlived in poverty in 2012,

compared to 33.8 percent of Hispanic children and 12.3 percent of white children.

24

13. Household debt is still high. Household debt equaled 103.8 percent of afer-tax

income in December 2013, down from a peak of 129.7 percent in December 2007.

25

A return to debt growth outpacing income growth, which was the case prior to the

start of the Great Recession in 2007, from already-high debt levels could eventu-

ally slow economic growth again. Tis would be especially true if interest rates also

rise from historically low levels due to a change in the Federal Reserves policies.

Consumers would have to pay more for their debt, and they would have less money

available for consumption and saving.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a professor

in the Department of Public Policy and Public Afairs at the McCormack Graduate School

of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusets, Boston. Jackie Odum is a

Special Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center.

6 Center for American Progress | Economic Snapshot: May 2014

Endnotes

1 Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product

Accounts (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2014).

2 Ibid.

3 Calculations are based on productivity growth (output

per hour) for nonfarm businesses from Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Current Employment Statistics (U.S. Department of

Labor, 2014).

4 Ibid.

5 The historical average refers to the average annualized

monthly residential sales from January 1963, when the

Census data started, to December 2007, when the Great

Recession started. Calculations are based on Bureau of the

Census, New Residential Sales Historical Data (U.S. Depart-

ment of Commerce, 2014).

6 Ibid.

7 National Association of Realtors, Existing Home Sales

Remain Soft in March, Press release, April 22, 2014.

8 Bureau of the Census, Housing Vacancies and Homeowner-

ship (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2014).

9 Congressional Budget Ofce, Updated Budget Projections:

2014 to 2024 (2014), available at http://www.cbo.gov/sites/

default/fles/cbofles/attachments/45229-UpdatedBudget-

Projections_2.pdf.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Richard Kogan and William Chen, Projected Ten-Year

Defcits Have Shrunk by Nearly $5 Trillion Since 2010, Mostly

Due to Legislative Changes (Washington: Center on Budget

and Policy Priorities, 2014), available at http://www.cbpp.

org/cms/?fa=view&id=4106.

13 Employment-growth data are calculated based on Bureau

of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics.

14 Ibid.

15 Calculations based on Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current

Population Survey (U.S. Department of Labor, 2014).

16 Bureau of the Census, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance

Coverage in the United States: 2012 (U.S. Department of Com-

merce, 2013). This report is occasionally referred to as the

poverty report.

17 Craig Copeland, Employment-Based Retirement Plan

Participation: Geographic Diferences and Trends, 2012

(Washington: Employee Beneft Research Institute, 2013).

18 Jenna Levy, U.S. Uninsured Rate Drops to 13.4%, Gal-

lup, May 5, 2014, available at http://www.gallup.com/

poll/168821/uninsured-rate-drops.aspx.

19 Ibid.

20 Unemployment numbers are taken from Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Current Population Survey.

21 Bureau of the Census, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance

Coverage in the United States: 2012.

22 Proft rates are calculated based on data from Board of Gov-

ernors of the Federal Reserve System, Release Z.1 Financial

Accounts of the United States (2014). Infation adjustments

are based on the Personal Consumption Expenditure Index

from Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and

Product Accounts.

23 Calculations based on Board of Governors of the Federal Re-

serve System, Release Z.1 Financial Accounts of the United

States.

24 Calculations based on Bureau of the Census, Income, Pov-

erty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2012.

25 Calculations based on Board of Governors of the Federal Re-

serve System, Release Z.1 Financial Accounts of the United

States.

You might also like

- Aging Dams and Clogged Rivers: An Infrastructure Plan For America's WaterwaysDocument28 pagesAging Dams and Clogged Rivers: An Infrastructure Plan For America's WaterwaysCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Paid Leave Is Good For Small BusinessDocument8 pagesPaid Leave Is Good For Small BusinessCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric vs. Reality: Child CareDocument7 pagesRhetoric vs. Reality: Child CareCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Addressing Challenges To Progressive Religious Liberty in North CarolinaDocument12 pagesAddressing Challenges To Progressive Religious Liberty in North CarolinaCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Closed Doors: Black and Latino Students Are Excluded From Top Public UniversitiesDocument21 pagesClosed Doors: Black and Latino Students Are Excluded From Top Public UniversitiesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Housing The Extended FamilyDocument57 pagesHousing The Extended FamilyCenter for American Progress100% (1)

- Leveraging U.S. Power in The Middle East: A Blueprint For Strengthening Regional PartnershipsDocument60 pagesLeveraging U.S. Power in The Middle East: A Blueprint For Strengthening Regional PartnershipsCenter for American Progress0% (1)

- An Infrastructure Plan For AmericaDocument85 pagesAn Infrastructure Plan For AmericaCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- 3 Strategies For Building Equitable and Resilient CommunitiesDocument11 pages3 Strategies For Building Equitable and Resilient CommunitiesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Preventing Problems at The Polls: North CarolinaDocument8 pagesPreventing Problems at The Polls: North CarolinaCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- A Progressive Agenda For Inclusive and Diverse EntrepreneurshipDocument45 pagesA Progressive Agenda For Inclusive and Diverse EntrepreneurshipCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- America Under Fire: An Analysis of Gun Violence in The United States and The Link To Weak Gun LawsDocument46 pagesAmerica Under Fire: An Analysis of Gun Violence in The United States and The Link To Weak Gun LawsCenter for American Progress0% (1)

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Wisconsin FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Wisconsin FamiliesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- How Predatory Debt Traps Threaten Vulnerable FamiliesDocument11 pagesHow Predatory Debt Traps Threaten Vulnerable FamiliesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Preventing Problems at The Polls: OhioDocument8 pagesPreventing Problems at The Polls: OhioCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Opportunities For The Next Executive Director of The Green Climate FundDocument7 pagesOpportunities For The Next Executive Director of The Green Climate FundCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Preventing Problems at The Polls: FloridaDocument7 pagesPreventing Problems at The Polls: FloridaCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- The Path To 270 in 2016, RevisitedDocument23 pagesThe Path To 270 in 2016, RevisitedCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- The Missing Conversation About Work and FamilyDocument31 pagesThe Missing Conversation About Work and FamilyCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Illinois FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Illinois FamiliesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Arizona FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Arizona FamiliesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- A Market-Based Fix For The Federal Coal ProgramDocument12 pagesA Market-Based Fix For The Federal Coal ProgramCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For Virginia FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For Virginia FamiliesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Great Leaders For Great Schools: How Four Charter Networks Recruit, Develop, and Select PrincipalsDocument45 pagesGreat Leaders For Great Schools: How Four Charter Networks Recruit, Develop, and Select PrincipalsCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Economic Security For New Hampshire FamiliesDocument4 pagesFast Facts: Economic Security For New Hampshire FamiliesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- A Quality Alternative: A New Vision For Higher Education AccreditationDocument25 pagesA Quality Alternative: A New Vision For Higher Education AccreditationCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Federal Regulations Should Drive More Money To Poor SchoolsDocument4 pagesFederal Regulations Should Drive More Money To Poor SchoolsCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- The Hyde Amendment Has Perpetuated Inequality in Abortion Access For 40 YearsDocument10 pagesThe Hyde Amendment Has Perpetuated Inequality in Abortion Access For 40 YearsCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Workin' 9 To 5: How School Schedules Make Life Harder For Working ParentsDocument91 pagesWorkin' 9 To 5: How School Schedules Make Life Harder For Working ParentsCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- A Clean Energy Action Plan For The United StatesDocument49 pagesA Clean Energy Action Plan For The United StatesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A General Guide To Camera Trapping Large Mammals in Tropical Rainforests With Particula PDFDocument37 pagesA General Guide To Camera Trapping Large Mammals in Tropical Rainforests With Particula PDFDiego JesusNo ratings yet

- Amar Sonar BanglaDocument4 pagesAmar Sonar BanglaAliNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of The DronesDocument43 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of The DronesVysual ScapeNo ratings yet

- C Exam13Document4 pagesC Exam13gauravsoni1991No ratings yet

- IELTS Vocabulary ExpectationDocument3 pagesIELTS Vocabulary ExpectationPham Ba DatNo ratings yet

- Finance at Iim Kashipur: Group 9Document8 pagesFinance at Iim Kashipur: Group 9Rajat SinghNo ratings yet

- Environmental Technology Syllabus-2019Document2 pagesEnvironmental Technology Syllabus-2019Kxsns sjidNo ratings yet

- Optimization of The Spray-Drying Process For Developing Guava Powder Using Response Surface MethodologyDocument7 pagesOptimization of The Spray-Drying Process For Developing Guava Powder Using Response Surface MethodologyDr-Paras PorwalNo ratings yet

- Doe v. Myspace, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 37Document2 pagesDoe v. Myspace, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 37Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Transformer Oil Testing MethodsDocument10 pagesTransformer Oil Testing MethodsDEE TOTLVJANo ratings yet

- Term Sheet: Original Borrowers) Material Subsidiaries/jurisdiction) )Document16 pagesTerm Sheet: Original Borrowers) Material Subsidiaries/jurisdiction) )spachecofdz0% (1)

- SOLVING LINEAR SYSTEMS OF EQUATIONS (40 CHARACTERSDocument3 pagesSOLVING LINEAR SYSTEMS OF EQUATIONS (40 CHARACTERSwaleedNo ratings yet

- Deluxe Force Gauge: Instruction ManualDocument12 pagesDeluxe Force Gauge: Instruction ManualThomas Ramirez CastilloNo ratings yet

- Expressive Matter Vendor FaqDocument14 pagesExpressive Matter Vendor FaqRobert LedermanNo ratings yet

- PW CDocument4 pagesPW CAnonymous DduElf20ONo ratings yet

- Diemberger CV 2015Document6 pagesDiemberger CV 2015TimNo ratings yet

- Lanegan (Greg Prato)Document254 pagesLanegan (Greg Prato)Maria LuisaNo ratings yet

- Piping MaterialDocument45 pagesPiping MaterialLcm TnlNo ratings yet

- (Variable Length Subnet MasksDocument49 pages(Variable Length Subnet MasksAnonymous GvIT4n41GNo ratings yet

- THE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEDocument29 pagesTHE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEedemaitreNo ratings yet

- Reinvestment Allowance (RA) : SCH 7ADocument39 pagesReinvestment Allowance (RA) : SCH 7AchukanchukanchukanNo ratings yet

- Cianura Pentru Un Suras de Rodica OjogDocument1 pageCianura Pentru Un Suras de Rodica OjogMaier MariaNo ratings yet

- JD - Software Developer - Thesqua - Re GroupDocument2 pagesJD - Software Developer - Thesqua - Re GroupPrateek GahlanNo ratings yet

- Statement of Compulsory Winding Up As On 30 SEPTEMBER, 2008Document4 pagesStatement of Compulsory Winding Up As On 30 SEPTEMBER, 2008abchavhan20No ratings yet

- NOTE CHAPTER 3 The Mole Concept, Chemical Formula and EquationDocument10 pagesNOTE CHAPTER 3 The Mole Concept, Chemical Formula and EquationNur AfiqahNo ratings yet

- Your Inquiry EPALISPM Euro PalletsDocument3 pagesYour Inquiry EPALISPM Euro PalletsChristopher EvansNo ratings yet

- AAU5243 DescriptionDocument30 pagesAAU5243 DescriptionWisut MorthaiNo ratings yet

- Weekly Choice - Section B - February 16, 2012Document10 pagesWeekly Choice - Section B - February 16, 2012Baragrey DaveNo ratings yet

- Benjie Reyes SbarDocument6 pagesBenjie Reyes Sbarnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Product CycleDocument2 pagesProduct CycleoldinaNo ratings yet