Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Notes Sect1 Ans Eng

Uploaded by

cherylrachelOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Notes Sect1 Ans Eng

Uploaded by

cherylrachelCopyright:

Available Formats

HKDSE

Interactive Geography

Notes

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard-prone areas?

(Teachers Edition)

HKDSE Interactive Geography

Aristo Educational Press Ltd. 2009

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

2

Unit 1 Where can we find tectonic hazards?

Natural hazard

A natural hazard is an unusual natural phenomenon or process that could cause loss

of life and damage to property.

In general, there are four types of natural hazards:

Examples

Tectonic hazards Earthquake, volcanic eruption and Tsunami

Geomorphic hazards Landslide and Avalanche

Climatic hazards Typhoon, flooding and drought

Biological hazards Disease and locuts

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

3

Global distribution patterns of the tectonic hazards

Refer to Fig.1.4 and Fig.1.5 in Section 1 p.9

Scientists have identified two regions where tectonic hazards are most active. They

are:

1. The Circum-Pacific

Belt

This runs around the Pacific Ocean. Most of the

earthquakes, volcanoes and sources of tsunamis on the

Earth can be found here.

It is known as the Pacific Ring of Fire because many

volcanoes are distributed in a circular pattern around the

Pacific Ocean.

2. The Alpine-

Himalayan Belt

This runs from the Alps in Europe to the Himalayas in

South Asia. It is a zone with a very active occurrence of

earthquakes.

Tectonic hazards can be found as well in East Africa and the middle of Atlantic Ocean.

The distribution of tectonic hazards coincides with plate boundaries.

Refer to Fig.1.6 in Section 1 p.10

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

4

Unit 2 What are the causes of tectonic hazards?

Structure of our Earth

Refer to Fig.2.1 and Fig.2.2 in Section 1 p.14

Refer to Table 2.1 in Section 1 p.15

Our Earth can be divided into three main layers:

Crust

It is the outermost part of the Earth, which is also the layer of the

Earths surface we live on.

It is a thin layer of brittle rock which consists of continental crust and

oceanic crust.

Continental crust is thicker and less dense than oceanic crust and it

forms all continental landmasses on Earth.

Mantle

It is the layer between the crust and the core.

It can be divided into two layers, the upper mantle and the lower

mantle.

The asthenosphere of the upper mantle is in semimolten state, while

the rest of the upper and lower mantle is solid.

The uppermost part of the mantle, together with the crust on top, is

called the lithosphere.

Core

It is the centre of the planet, which is made of extremely dense

materials under high temperature and pressure.

The core is divided into two layers: the solid inner core and the

molten outer core.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

5

Plate tectonics theory

It is the study of plate movement and interaction, as well as crustal formation and

destruction which results in many landforms we commonly find on earth.

The theory also provides reasonable explanations of the causes of many tectonic

hazards.

Plates

Refer to Fig.2.5 in Section 1 p.17

The Earth is completely covered by a layer of crust. According to the plate tectonics

theory, the crust is made up of different pieces called tectonic plates or plates.

The plates are large pieces of solid landmass floating on the asthenosphere which

form the Earths surface.

A plate may be composed of oceanic crust or continental crust, or both.

Some plates such as the Pacific Plate are dominated by oceanic crust. Other plates

such as the Eurasian Plate are composed mainly of continental crust.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

6

Movement of plates

Refer to Fig.2.8 in Section 1 p.20

The movement of plates is driven by the convection currents in the mantle.

Owing to the high temperature of the core, mantle material near the core is heated and

rises up. As it comes closer to the top of the mantle, it cools slowly and descends. It is

then heated again when it gets closer to the core.

In this way, the convection currents in the mantle are formed, providing strong forces to

drive the plates to converge, diverge or move sideways.

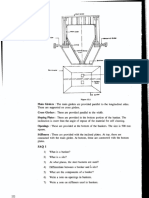

Different types of plate boundaries

1. Constructive

plate boundaries

It is formed where two adjacent plates move apart from each

other, creating tensional force in between.

New crust is produced here as magma rises to the Earths

surface, cools and solidifies.

It is also called a divergent plate boundary.

2. Destructive

plate boundaries

It is formed where two adjacent plates move towards each

other, creating compressional force in between.

As two plates collide, the higher-density plate will sink beneath

the lower-density plate. The denser plate is then pushed into

the mantle and melted.

It is also known as a convergent plate boundary.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

7

3. Conservative

plate boundaries

It is formed where two adjacent plates slide past one another

laterally along a transform fault.

Shear stress is created along the boundary but no crust is

formed nor destroyed.

Destructive plate boundary

Conservative plate

boundary

Constructive plate boundary

Types of plate boundaries

Processes associated with plate movements

3.1 Folding

When compressional forces are applied to rock, the rock will be folded and deformed.

Folding takes place on different scales:

- Small-scale folds can be found in various places in Hong Kong, such as Ma Shi

Chau and Lai Chi Chong.

- On a global scale, we can find fold mountains such as the Himalayas and the

Andes, which are formed by the collision of two landmasses.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

8

Rock before folding

Rock after folding

3.2 Faulting

Faulting occurs along the lines of weakness of rocks.

When tensional force, compressional force or shear stress is greater than the rock can

withstand, the rock will break along the fault plane and faulting occurs. This causes the

rock to displace either vertically or horizontally.

Fault plane

Fault line

Rock after faulting

Rift valleys and block mountains are the most typical large-scale landforms that are

formed by faulting.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

9

Formation of rift valley

Before After

Tensional

force

Compressional

force

Formation of block mountain

Before After

Tensional

force

Compressional

force

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

10

3.3 Vulcanicity

Refer to Fig.2.16 in Section 1 p.25

Plate movements and their associated tectonic forces produce lines of weakness in the

crust. As a result, magma and gases in the mantle either extrude onto the Earths

surface or intrude into the Earths crust. This process is called vulcanicity.

The most conspicuous landform related to vulcanicity on the Earths surface is a

volcano.

Landforms can be found at constructive plate boundaries

1. Rift valleys

When two continental crusts are pulled apart by tensional forces, faults are formed in

the middle and the crust is split into huge blocks.

As the two crusts move further apart, the huge blocks of crust sink due to gravity. A rift

valley is thereby formed.

Example: East African Rift Valley

Volcanoes can be found along the rift valley as magma rises up through lines of

weakness, while lakes are also created at some deeper locations of the rift valley.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

11

Rift

Valley

Formation of a rift valley

Refer to the case study of East African Rift Valley in Section 1 p.30

2. Mid-oceanic ridges

Under the sea, when two oceanic crusts move away from each other, magma rises up

from the mantle through lines of weakness to the surface. Then it cools and solidifies

to form new crust.

As the uprising of magma continues, newly formed crust is gradually pushed away

from the plate boundary. This process is called sea-floor spreading.

Repeated uprising and solidification of magma form mid-oceanic ridges.

Examples: The Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the East Pacific Rise

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

12

Mid-oceanic ridge

Crust moves apart

Formation of a mid-oceanic ridge

Refer to the case study of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in Section 1 p.31

Refer to the case study of the East Pacific Rise in Section 1 p.32

3. Volcanoes and volcanic islands

Volcanoes are often found at the plate boundaries where hot magma can rise to the

Earths surface through lines of weakness.

Volcanic islands are formed when volcanoes on the sea floor emerge at the sea

surface after repeated eruptions.

Examples: Iceland and Easter Island

Formation of a volcanic island

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

13

Landforms can be found at destructive plate boundaries

When a continental crust collides with an oceanic crust, the crust with higher density

(oceanic crust) is pushed beneath the crust with lower density (continental crust).

The denser crust then sinks into the hot mantle and melts. This process is known as

subduction and a subduction zone is created.

Crust of higher density

is subducted

Subduction zone

Cross section of a subduction zone

When two continental crusts collide, no subduction zone is formed. Instead, sediments

and crustal materials at the plate margin are pushed up to form fold mountains.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

14

1. Ocean trenches

Refer to Fig.2.30 in Section 1 p.34

Along subduction zones, long and narrow undersea troughs are formed, running

parallel to plate boundaries. These are known as ocean trenches.

2. Volcanoes and island arcs

Volcanoes are also common on the Earths surface above subduction zones.

Melted crustal materials at a subduction zone are less dense than the mantle.

Therefore, they rise to the Earths surface along cracks in the crust and form

volcanoes.

These volcanoes usually form a curved chain running parallel to the plate boundaries,

therefore known as island arcs (over the sea) or continental arcs (over a continent).

Refer to the case study of Island arc - Japan in Section 1 p.34

Island arc Ocean trench

Volcano

Ocean trench, volcano and island arc are formed when two oceanic

crusts collide

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

15

3. Fold mountains

a. Oceanic- continental collision

When a continental crust collides with an oceanic crust, the oceanic crust subducts

into the mantle due to higher density.

The sedimentary rocks on the ocean floor are compressed, folded and pushed up to

form a mountain belt called a fold mountain range. It runs parallel to the plate

boundary.

Example: The Andes in South America

Refer to the case study of the Andes in Section 1 p.35

b. Continental- continental collision

Refer to Fig.2.35 in Section 1 p.36

When two continental crusts collide, neither one is pushed into the mantle because of

similar density.

The sedimentary rocks and crustal materials are crushed, compressed and pushed

upward to form a huge fold mountain range.

As there is no subduction, volcanoes and volcanic eruptions are absent at this type of

plate boundary (continental-continental collision), but earthquakes are quite common.

Example: The Himalayas

Refer to the case study of the Himalayas in Section 1 p.36

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

16

50 million

years ago

Present

Formation of the Himalayas

Landforms can be found at conservative plate boundaries

Transform faults

When two plates slide past each other

laterally, shear stress builds up along the

plate boundary.

If the stress is too great, the plates will

fracture and produce a transform fault

along which many earthquakes occur.

Example: San Andreas Fault

Structure of a transform fault

Refer to the case study of San Andreas Fault

in Section 1 p.38

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

17

Natural hazards found along plate boundaries

1. Earthquakes

An earthquake is a sudden shaking of the ground.

As plates move, compressional and tensional force or shear stress will develop along

plate boundaries.

Stress is created and accumulated at the plate boundary until the plate fractures. This

sudden release of stress produces seismic waves which propagate in all directions,

causing the ground to shake (earthquake).

The point where the crust suddenly fractures and releases seismic waves is called a

focus, and the point on the Earths surface vertically above the focus is known as an

epicentre.

Refer to Fig.2.43 in Section 1 p.40

Earthquakes which occur at constructive and conservative plate boundaries are

limited to the areas along the plate boundary, and they are mainly shallow-focus

earthquakes.

At destructive plate boundaries, subduction of one plate creates an earthquake zone

deep in the crust. Earthquakes of various depths can be found here. The area

affected by earthquakes is also much larger.

Refer to Fig.2.45 in Section 1 p.41

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

18

2. Volcanic eruptions

Convection currents in the mantle drift the plates to converge or diverge. As a result,

strong tensional and compressional forces are exerted on the crusts at the plate

boundaries, creating lines of weakness.

When the pressure beneath the Earths surface becomes very high, magma and

gases are pushed up to the surface through lines of weakness or vents, causing a

volcanic eruption.

When a volcano erupts, gases (such as sulphur dioxide), lava and pyroclastic are

ejected.

Violent eruptions may also cause earthquakes and tsunamis.

3. Tsunamis

Refer to Fig.2.47 in Section 1 p.42

Tsunamis are very big sea waves caused by geological activities.

Most tsunamis are triggered by strong earthquakes that occur under the sea floor,

whereas some are caused by particularly violent volcanic eruptions or landslides

under the sea.

The dramatic tremor in the sea produces big waves, but they are usually not

noticeable in deep sea. The waves become prominent when they reach the coastlines,

causing devastating effects on the coastal areas.

As the earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are most frequent at the plate boundaries,

most of the sources of tsunamis are also found there.

The coastal areas around the Pacific Ocean are especially vulnerable to tsunamis due

to active tectonic activities in the region.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

19

Reasons that some earthquakes located far away from plate boundaries

1. Intraplate earthquakes

Intraplate earthquakes are earthquakes which occur

within the interior part of plates.

The causes of intraplate earthquakes:

- In general, many of these earthquakes are the

result of fault rupture or displacements in fault

zones.

Refer to Fig.2.49 in Section 1 p.46

2. Human activities

Human activities and artificial structures may trigger

earthquakes due to exertion of pressure on land.

Examples:

- the heavy weight of water stored in a large

reservoir

- violent explosions caused by humans, such as

nuclear testing

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

20

Reasons that some volcanic eruptions not happen along plate

boundaries

Hot spots

Refer to Fig.2.51 in Section 1 p.48

The formation of hot spots is caused by uneven heat distributions in the mantle.

Columns of hot material are buoyant enough to rise from the mantle to the Earths

surface through an opening. Therefore, volcanic activities are common at hot spots.

Hot spots can be found both at plate boundaries and in the middle of plates.

The positions of some hot spots remain relatively fixed.

As tectonic plates move over a fixed column of hot mantle material, a chain of

volcanoes following the direction of plate movement will be formed.

Example: Hawaii

Refer to Fig.2.52 and 2.53 in Section 1 p.48

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

21

Unit 3 What are the effects of tectonic hazards?

Factors affecting the power of tectonic hazards

1.1 Characteristics of the hazard events

1. Magnitude

and intensity

a. Earthquakes

Magnitude:

- the energy released by an earthquake

- usually measured on the Richter Scale

Intensity:

- the destruction caused by an earthquake to

human settlements and natural environment

- usually measured on the Modified Mercalli

Intensity Scale

- The higher number of the scales, the greater the

destruction.

Refer to Table 3.1 in Section 1 p.53

The intensity of an earthquake depends on two

factors:

- distance from the epicenter

- depth of the earthquake

Usually the closer to the epicentre, the greater the

intensity an area will experience.

An earthquake with a shallow focus brings more

destructive effects than a deep earthquake.

Refer to Fig.3.1 and Fig.3.2 in Section 1 p.52

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

22

b. Volcanic

eruptions

The way that a volcano erupts affects its power of

destruction.

In general, volcanic eruptions can be classified as

explosive and gentle.

Most explosive volcanic eruptions are found along

destructive plate boundaries, and they usually cause

greater damage than gentle eruptions.

1. Magnitude

and intensity

c. Tsunamis

The power of a tsunami is determined by the strength

of its sources.

If the tsunami is triggered by an earthquake, the

greater the magnitude of the earthquake, the bigger

the tsunami.

Coastal regions with low-lying relief will be damaged

more significantly by the big waves.

The intensity of a tsunami is usually represented by its

run-up height, i.e. the maximum height of the waves.

In general, the greater the run-up height, the further

inland the waves will reach, leading to more damage

and casualties.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

23

2. Frequency

of

occurrence

Frequency of occurrence means how often a hazard recurs.

A volcano may remain dormant for decades since its previous

eruption.

Earthquakes recur more often especially along the area of plate

boundary.

Refer to Table 3.2 in Section 1 p.54

3. Duration

Duration measures how long a hazard event lasts.

In general, the longer the duration, the more damage can be possibly

brought.

4. Areal

extent

Areal extent refers to the size of an area impacted by a hazard event.

While volcanic eruptions are usually localised events, earthquakes

under oceans may trigger tsunamis that affect all coastal regions

around the ocean.

5. Speed of

onset

Speed of onset means how fast a hazard event occurs.

Tectonic hazards usually occur in a sudden and this makes prediction

and warning difficult.

1.2 Societal conditions of the affected areas

1. Population

density

The higher the population density of an affected area, the greater

the casualties and economic loss that will be caused by the

event.

2. Preparedness

of people

If citizens of an affected area prepare well for the hazard, they will

know how to react properly when a hazard occurs.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

24

3. Monitoring

and warning

system

If a place is equipped with monitoring and warning systems for

hazards, scientists can give warnings before a hazard occurs.

This can help reduce the casualties and economic losses through

earlier evacuation and proper preparations.

The effects of earthquakes

1. Primary effects

effects that happen immediately and directly as a result of ground shaking.

a. Fault rupture and

deformation of

ground

Along the active fault line where an earthquake occurs, ground

surfaces may rupture and displace, causing cracks and

deformations.

b. Ground shaking

Ground shaking is a direct result of energy released from the

focus when seismic waves reach the ground surface.

Such shaking may destroy buildings and other structures at the

epicentre or areas nearby.

c. Aftershocks

Aftershocks often follow an earthquake.

These tremors may continue for several weeks to months,

causing further destruction to affected areas.

Refer to the case study in Section 1 p.58

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

25

2. Secondary effects

the impacts and damage caused by the primary ground shaking effect

a. Landslides

When there is a violent shaking of ground, loose materials and

debris on slopes may move down.

Large-scale landslides will be triggered in areas with steep

relief and unstable slopes.

b. Soil liquefaction

During an earthquake, the pressure of ground water increases.

If the soil is poorly compacted, soil liquefaction may occur when

soil particles mix with ground water.

The strength of the soil in supporting the foundations of

buildings will be severely weakened. Therefore, buildings may

sink and collapse.

c. Flooding

A strong earthquake may damage dams or other waterworks

along a river.

The water from the river or reservoir would then flood

downstream areas in a very short time, leading to casualties

and economic losses.

d. Tsunamis

If the earthquake occurs under the sea, the tremor may cause a

tsunami.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

26

e. Disruption of

transport

Cities are linked by many highways, railways and road

networks. All these transport networks form important lifelines

to a city.

Any damage to the lifelines will make rescue more difficult and

delay resumption of normal life.

f. Disruption of

communications

Communications through telephone and Internet may be

interrupted if the earthquake damages underground cables.

This reduces the efficiency of rescue and contributes to further

economic loss.

g. Fire hazards

If an urbanised area is struck by an earthquake, gas pipes and

electricity networks will be damaged.

Fires may break out as a result of gas leakage or electrical

short circuits. This may lead to more casualties.

h. Disease and

epidemics

If there is no prompt action to bury dead bodies and maintain

supplies of clean water after an earthquake, disease and

epidemics like malaria may spread among victims which cause

further casualties and suffering.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

27

The effects of volcanic eruptions

1. Short term effects

a. Lava flows

Lava flow can endanger our lives and cause extensive

economic loss.

Less viscous lava can move at speeds of up to 50 km per

hour on steep slopes, and can spread quickly over tens of

kilometres from the volcano. The lava will burn everything it

passes through.

b. Pyroclastic flows

and ash fall

When a volcano erupts, mixtures of lava particles, rock

fragments and volcanic ash are ejected from the volcano.

These pyroclastic materials, together with hot gases, travel

downhill at high speed due to gravity. This is known as a

pyroclastic flow.

The high temperature of gases and large pieces of rock

(volcanic bombs) may kill people.

The volcanic ash blows into the atmosphere to form eruption

clouds. Areas around the volcano will be covered with

volcanic ash when it is deposited. Daily lives of people are

seriously disturbed.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

28

c. Gases

Active volcanoes produce large amounts of water vapour and

gases such as carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, hydrogen

sulphide and carbon monoxide.

Carbon dioxide can drive oxygen away, making humans and

animals suffocate.

Acid gases like sulphur dioxide may attack our respiratory

system and also cause acid rains which damage the

environment.

Some gases emitted are even poisonous, such as hydrogen

sulphide.

d. Thunderstorms

and mudflow

When large amounts of volcanic ash and dust are injected into

the atmosphere, they act as condensation nuclei which speed

the formation of water droplets, causing heavy rainstorms and

thunderstorms.

Mudflow occurs when volcanic materials are mixed with

rainwater and flow quickly through river valleys and low-lying

areas.

e. Landslides

Landslides may occur when the slope of the volcano is steep

and unstable, or when the eruption is particularly violent.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

29

f. Earthquakes

Before or during a volcanic eruption, the release of

accumulated pressure and gases under the ground may

cause violent shaking of the crust, resulting in earthquakes.

g. Tsunamis

If a volcanic eruption occurs under the sea, the great shock

generated may trigger a tsunami.

Low-lying coastal regions may suffer severe damage as a

result.

2. Long term effects

a. Drop in global

temperature

During a volcanic eruption, large amounts of volcanic ash are

ejected into the stratosphere where it reflects incoming solar

radiation back to space. This leads to a regional or even a

global drop in air temperature.

As it takes a very long time for the ash to settle, local and

global climate may be affected for several years as a result of

a volcanic eruption.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

30

b. Acid rain

When a volcano erupts, dissolved gases in magma are

released. When these gases, particularly sulphur dioxide and

hydrogen sulphide, are mixed with rainwater, acid rain results.

This may destroy natural habitats and damage human

settlements.

c. Destruction of

natural habitats

A volcanic eruption often destroys nearby natural habitats

directly.

Ecological restoration may take decades.

d. Famines and

epidemics

Apart from the deaths caused by direct hazards like

pyroclastic flow, a volcanic eruption may bring further deaths

due to famine and epidemic, particularly in less developed

countries.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

31

Benefits brought by volcanic eruptions

a. Fertile soil

The volcanic ash and lava ejected during an eruption are

rich in minerals.

This makes the farmlands near volcanoes more fertile

and good for farming.

b. Attractive landforms

for tourists

Volcanic eruptions may produce different landforms,

such as crater lakes and lava domes.

These scenic landforms, together with hot springs near

them, are attractive to tourists.

c. Geothermal energy

The high temperatures brought by underground magma

flows make the use of geothermal energy possible,

which is beneficial to humans.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

32

The effects of tsunamis

1. Short term effects

a. Sweep effect

When a series of tsunami waves rush ashore, the strong

swash actions will sweep everything on the shore towards

inland.

This causes direct destruction of human settlements and the

environments along the coast. Most deaths are caused by

drowning when the waves sweep ashore.

The destruction caused by sweep effect is more significant

along coastal areas with gentle relief.

Sea waves may reach several kilometres inland in case of

large-scale tsunami, causing massive destruction.

b. Flooding

A tsunami may also bring temporary flooding to the affected

areas when a lot of sea water rushes inland.

Most flooding ends when the sea level returns to normal.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

33

2. Long term effects

a. Change of

coastline

After a devastating tsunami, the coastline of affected areas

may be changed permanently.

b. Damage of the

ecosystem

The marine ecology may also be seriously affected.

Example: Coral reefs may be destroyed by large waves

during the passage of a tsunami. Such damage may take

decades to recover.

c. Interruption of

the local economy

After a tsunami, economic activities in affected areas will be

interrupted or even halted.

The more serious the damage to infrastructure, the slower the

resumption of normal economic activities.

Tourists may also avoid visiting places where a tsunami has

just occurred. This slows economic recovery of the affected

areas, especially for those that rely heavily on tourism.

Refer to the case stud of 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami in Section 1 p.72

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

34

Measures used to reduce the impact of tectonic hazards

3.1 Preparatory measures before hazard events

1. Monitoring and

predicting

systems

Advanced technology allows us to better understand how and

what precursors may take place before the onset of hazards.

Earth scientists can use different instruments and technologies to

monitor the anomalies before a volcanic eruption, such as

changes in the underground water level, shaking of the volcano,

or volcanic gas emissions.

Although it is still very difficult to predict the exact time and place

of an earthquake, a network of seismographic stations may give

scientists up-to-date information on crustal activities for further

research.

This also helps locate the epicentres of earthquakes more

accurately and increase the efficiency of rescue operations.

2. Issue warnings

With the help of monitoring and predicting systems, scientists are

able to issue timely warnings, especially for volcanic eruptions

and tsunamis.

Governments can evacuate affected populations before the

hazard occurs to reduce the number of casualties.

To monitor tsunamis in the Pacific Ocean region, the Pacific

Tsunami Warning Centre has been set up.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

35

- The centre monitors the earthquakes occurring around the

Pacific Ocean and assesses their possibilities of triggering

tsunamis.

- It will issue warnings to the governments of affected countries

when necessary.

Refer to Fig.3.29 in Section 1 p.78

3. Risk

assessment

mapping

Scientists have analysed the chance of hazards occurring at

different places. Such information can be presented in the form

of hazard maps.

The risk assessment mapping can help people prepare better for

possible hazards in the future.

Refer to Fig.3.30 in Section 1 p.79

4. Land use

zoning

Risk assessment mapping done on a local scale can be used by

governments for land use zoning.

Areas with a higher risk of hazards can be identified on a hazard

map. Planners can zone these areas for low-density

development with fewer human settlements and activities.

Example: Along the coastal areas vulnerable to tsunami attacks,

buffer zones such as green belts can be designated. This can

reduce the impact of hazards when they occur.

Refer to Fig.3.31 and Fig.3.32 in Section 1 p.79

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

36

5. Education and

drills

A government should educate its citizens about potential hazards

and their signs and impact.

Regular drills should be conducted so that people know what

actions (e.g. evacuation) should be taken to protect themselves if

a hazard occurs.

6. Improve

building design

and set up

building

regulations

Casualties can be reduced by improving building designs with

reinforced structures, such as shear walls, cross-bracing and

base isolators.

Governments should set up laws and regulations to ensure all

new buildings are built with designs that can withstand strong

earthquakes, especially in earthquake-prone regions.

Refer to Fig.3.37a and b in Section 1 p.82

7. Buy insurance

We can buy insurance in advance to reduce economic losses

caused by the hazard.

The money recovered can be used for reconstruction after the

hazard.

3.2 Immediate actions after hazard events

1. Prompt

rescue and

medical

services

After a hazard, prompt rescue actions can save many lives and good

medical services can ensure a greater chance of survival.

The government should organise efficient rescue teams equipped

with the most advanced tools to minimise casualties.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

37

2. Efficient aid

and clean-up

Survivors of a hazard event are often homeless and lack basic

necessities.

Therefore, it is important for the government to provide them with

immediate aid such as shelters, clean water, food and other

necessities. Hygiene must be maintained in affected areas.

These measures can help prevent deaths caused by famine and

outbreak of disease after a hazard.

3.3 Remedial measures after hazard events

1. Implementation

of rehabilitation

programmes

After a hazard, infrastructure and human settlements may be

severely damaged.

The government needs to carry out comprehensive

rehabilitation programmes to rebuild the affected areas.

2. Help people

overcome

traumatic

experiences

While physical damage can be recovered in a short period of

time, psychological trauma of the survivors may last for a long

time.

Many people may have lost family members and friends in the

hazard, or have suffered great economic losses. Such

traumatic experiences make it difficult for them to return their

lives to normal.

Counselling services should be provided to help them recover

from such painful experiences.

Refer to Fig.3.41 in Section 1 p.84

Refer to the case study of 1995 Kobe earthquake in Section 1 p.85

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

38

Factors affecting the effectiveness of these measures

1. Technological

limitations

Sometimes scientists may issue false warnings due to

inaccurate predictions, while in other cases hazards come

unexpectedly and cause serious casualties.

This is especially true for the prediction of earthquakes, as the

technologies available today are still unable to predict the exact

location, magnitude and time of potential earthquakes.

For volcanic eruptions and tsunamis, the warnings are relatively

more accurate but still not entirely reliable.

2. Government

enforcement

Many administrative measures such as defining building

regulations and formulating evacuation plans should be done

by the government.

Therefore, the effectiveness of these measures depends

heavily on enforcement by government officials.

If they do not fully implement the measures, effectiveness will

be reduced.

3. Participation by

the public

Education and regular drills are important measures to help

citizens become familiar with actions to take when hazards

occur.

However, this requires active participation by the public.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

39

4. Adoption of

appropriate

measures

Even if an advanced prediction system can give accurate

predictions of dangerous hazard events, casualties cannot be

reduced if there is no proper plan of evacuation or buildings are

too weak to withstand the hazards.

5. Adequate

preparations

Adequate preparations are very important to make measures

effective.

6. Financial

constraints

The success of all measures used to minimise the impacts of

natural hazards depends on the financial strength of the

government.

If the government does not have enough money to fully carry

out the programmes and measures needed, their effectiveness

will be reduced.

This explains why less developed countries are more

vulnerable to natural hazards.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

40

Unit 4 The choice to live in hazard-prone areas

Reasons for less developed areas suffer more from natural hazards

1. Socio-economic

gap

Less developed areas are usually poorer.

Although there are many measures to reduce the impact of

natural hazards, most of them are too expensive for the less

developed areas to adopt.

The lack of resources also leads to other problems, such as

inadequate medical services and inefficient rescue after

hazards.

The governments are also unable to have their properties

insured due to financial limitations.

2. Technological

gap

Many less developed areas lack resources to buy or develop

the equipment needed.

This creates a technological gap between the less developed

and the more developed areas. Therefore, the less developed

areas are poorly prepared for the hazards.

3. Poor

communication

and infrastructure

Communication and infrastructure such as transport networks

are less efficient in less developed areas, especially in remote

villages.

This makes prompt rescue more difficult and increases the

number of casualties when hazards occur.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

41

4. Low literacy

level and lack of

awareness

Citizens in less developed areas usually have less education.

Some of them are even illiterate.

Therefore, they have little knowledge about natural hazards

and they are unable to prepare for and protect themselves

from the hazards properly.

5. Poor governance

Many government officials in less developed areas do not

know very well how to prepare for natural hazards.

Laws and regulations that can reduce the impact of hazards

(such as land use zoning and emergency plans) may be

absent.

Corruption is often common in less developed areas, which

makes enforcement of regulations against hazards less

effective.

International cooperation helping less developed areas tackle hazards

International organisations, science agencies and more developed areas can help the

less developed areas better prepare for hazards through information exchange,

technology transfers and financial aid.

Other voluntary organisations such as International Federation of Red Cross and Red

Crescent Societies, Mdecins Sans Frontires (MSF) and World Vision also pay

attention to hazards around the world, particularly in less developed areas.

They provide immediate humanitarian and medical aid to the people who suffer from

hazards. Community rehabilitation programmes are also offered.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

42

Causes driving people leave a hazard-prone area

1. Past experience

of hazards

People who have experienced a major disaster in the past

may feel scared of having another one in the future.

To avoid this frightening experience, they may choose to

leave that location and move to a place where they feel safer.

2. High probability

of having hazards

With the help of advanced technology and past hazard

records, we can identify high risks locations.

People can choose to move to the low-risk region so as to

reduce their exposure to natural hazards.

Reasons for people still live in hazard-prone areas

1. Supply of natural

resources

There are many natural resources in areas along the

plate boundaries.

Deposition of volcanic ash and the weathering of

solidified lava around volcanoes form fertile soil.

Mineral deposits are formed in areas with large-scale

active tectonic activities.

Geothermal energy resources can also be developed in

volcanically active regions.

Landforms such as hot springs and volcanoes, are also

good attractions for tourists.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

43

2. Good climate

Some hazard-prone areas lie within climatic zones which

are good for farming activities and comfortable to live in,

i.e. tropical and subtropical regions.

3. Well-developed with

good facilities

Some high-risk areas, such as big cities in the USA and

J apan, have a long history of development. They are

well-developed with good infrastructure and facilities,

giving a higher living standard and attract a lot of people.

These cities usually have developed a good mechanism

to manage natural hazards. People are less willingly to

move to other places.

4. No choice

In less developed areas, such as the Philippines and

Indonesia, people are too poor to migrate to other

places. They have no choice but to stay and live with the

risk of natural hazards where they are.

5. Inertia

People often do not want to change their living places

because of established social networks, career and

business ties.

Unless a threat is imminent and serious, they will choose

to stay in the place where they are used to living.

Section 1

Opportunities and risks

Is it rational to live in hazard prone areas?

44

6. Underestimation of

hazards

Many people think it is unlikely for them to experience a

big natural hazard event.

However, the possibility of a big one does exist, and past

records cannot provide accurate predictions for the time

and magnitude of future events.

7. There is no safe

place anywhere

There is no place that is completely free of natural

hazards.

Therefore, many people think there is very little they can

do to avoid hazards. They will remain where they are as

long as the risk of hazards is acceptable to them.

You might also like

- 4gNSS20112012 Exam1 Paper1 Qa STDocument22 pages4gNSS20112012 Exam1 Paper1 Qa STcherylrachelNo ratings yet

- Notes Sect2 EngDocument62 pagesNotes Sect2 EngcherylrachelNo ratings yet

- Lexical Change and VariationDocument20 pagesLexical Change and VariationcherylrachelNo ratings yet

- Notes Sect2 Ans EngDocument62 pagesNotes Sect2 Ans EngcherylrachelNo ratings yet

- Gas Exchange in HumansDocument9 pagesGas Exchange in HumanscherylrachelNo ratings yet

- Be Careful at The Book Club, The Author Might Be ThereDocument14 pagesBe Careful at The Book Club, The Author Might Be TherecherylrachelNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 123 09-Printable Menu VORDocument2 pages123 09-Printable Menu VORArmstrong TowerNo ratings yet

- Updated Factory Profile of Aleya Apparels LTDDocument25 pagesUpdated Factory Profile of Aleya Apparels LTDJahangir Hosen0% (1)

- 4 Force & ExtensionDocument13 pages4 Force & ExtensionSelwah Hj AkipNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Notes The White Bird Reading The Image Painting Analysis PDFDocument4 pagesModule 1 Notes The White Bird Reading The Image Painting Analysis PDFMelbely Rose Apigo BaduaNo ratings yet

- Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma - PPTX Essam SrourDocument10 pagesNasopharyngeal Angiofibroma - PPTX Essam SrourSimina ÎntunericNo ratings yet

- Native Data Sheet Asme b73.1Document4 pagesNative Data Sheet Asme b73.1Akhmad Faruq Alhikami100% (1)

- Plans PDFDocument49 pagesPlans PDFEstevam Gomes de Azevedo85% (34)

- Faa Registry: N-Number Inquiry ResultsDocument3 pagesFaa Registry: N-Number Inquiry Resultsolga duqueNo ratings yet

- Stalthon Rib and InfillDocument2 pagesStalthon Rib and InfillAndrea GibsonNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Throughout The Life Span 7th Edition Edelman Test BankDocument35 pagesHealth Promotion Throughout The Life Span 7th Edition Edelman Test Bankcourtneyharrisbpfyrkateq100% (17)

- Elements of Romanticism in The Poetry of W. B. Yeats: Romantic InfluencesDocument8 pagesElements of Romanticism in The Poetry of W. B. Yeats: Romantic InfluencesSadman Shaid SaadNo ratings yet

- Combined Shear and TensionDocument16 pagesCombined Shear and TensionDAN MARK OPONDANo ratings yet

- 3rd Quarter Exam (Statistics)Document4 pages3rd Quarter Exam (Statistics)JERALD MONJUANNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus: Course Code Course Title ECTS CreditsDocument3 pagesCourse Syllabus: Course Code Course Title ECTS CreditsHanaa HamadallahNo ratings yet

- DOC-20161226-WA0009 DiagramaDocument61 pagesDOC-20161226-WA0009 DiagramaPedroNo ratings yet

- FemDocument4 pagesFemAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Dual Shield 7100 Ultra: Typical Tensile PropertiesDocument3 pagesDual Shield 7100 Ultra: Typical Tensile PropertiesDino Paul Castro HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Sat Vocabulary Lesson and Practice Lesson 5Document3 pagesSat Vocabulary Lesson and Practice Lesson 5api-430952728No ratings yet

- Main Girders: CrossDocument3 pagesMain Girders: Crossmn4webNo ratings yet

- A Year On A FarmDocument368 pagesA Year On A FarmvehapkolaNo ratings yet

- Goliath 90 v129 eDocument129 pagesGoliath 90 v129 eerkanNo ratings yet

- Gemh 108Document20 pagesGemh 108YuvrajNo ratings yet

- Bảng giá FLUKEDocument18 pagesBảng giá FLUKEVăn Long NguyênNo ratings yet

- JKJKJDocument3 pagesJKJKJjosecarlosvjNo ratings yet

- User'S Guide: Tm4C Series Tm4C129E Crypto Connected Launchpad Evaluation KitDocument36 pagesUser'S Guide: Tm4C Series Tm4C129E Crypto Connected Launchpad Evaluation KitLương Văn HưởngNo ratings yet

- Middle Range Theory Ellen D. Schulzt: Modeling and Role Modeling Katharine Kolcaba: Comfort TheoryDocument22 pagesMiddle Range Theory Ellen D. Schulzt: Modeling and Role Modeling Katharine Kolcaba: Comfort TheoryMerlinNo ratings yet

- 02-Building Cooling LoadsDocument3 pages02-Building Cooling LoadspratheeshNo ratings yet

- Sony Cdm82a 82b Cmt-hpx11d Hcd-hpx11d Mechanical OperationDocument12 pagesSony Cdm82a 82b Cmt-hpx11d Hcd-hpx11d Mechanical OperationDanNo ratings yet

- TM-8000 HD Manual PDFDocument37 pagesTM-8000 HD Manual PDFRoxana BirtumNo ratings yet

- NF en Iso 5167-6-2019Document22 pagesNF en Iso 5167-6-2019Rem FgtNo ratings yet