Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3mon Pol-State of Financial Sector Regulation and Competition in India-November 13-2011

Uploaded by

Rajat Kaushik0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views21 pages3Mon Pol-State of Financial Sector Regulation and Competition in India-November 13-2011

Original Title

3Mon Pol-State of Financial Sector Regulation and Competition in India-November 13-2011

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document3Mon Pol-State of Financial Sector Regulation and Competition in India-November 13-2011

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views21 pages3mon Pol-State of Financial Sector Regulation and Competition in India-November 13-2011

Uploaded by

Rajat Kaushik3Mon Pol-State of Financial Sector Regulation and Competition in India-November 13-2011

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 21

1/21

State of financial sector regulation and competition in India

A B Rastogi

1

NMIMS University

Mumbai 400 056

1. Introduction

Financial sector regulation witnessed lessening of onerous regulation or

deregulation in the name of enhancing competition among financial sector firms

and service providers in the last three decades. The underlying principles of

deregulation have been to achieve market efficiency and reducing regulatory

cost. This principle is derived from the overarching belief that market efficiency

leads to protection of consumers and depositors and solvency of financial

institutions.

The 2008 credit crisis unfolded the downside of excessive deregulation and

shortcoming of light handed approach to regulation. The deregulation allowed

development of financial institutions to become too big to fail. This perception of

financial institutions that they will not be allowed to fail as it was done in the past

in the US and the UK

2

, allowed them to take excessive risk because profits of

these institutions remained private whereas losses were borne by public directly

or indirectly. The size of some of these institutions allowed them to influence

political economy of regulators and stimulated irresponsible behavior on their

part in developed economies. With the help of hindsight one can say that the

2008 crisis was the result of lack of regulation in different markets and institutions

(credit, housing, rating agencies etc.), improper implementation of existing

regulation, regulatory overlap, failure of models in calculating different risks

(particularly liquidity risk) and interdependence of markets.

Indian economy came out of the credit crisis comparatively unharmed. Both,

financial institutions and real economy measured in terms of jobs and economic

growth reached pre-crisis level in roughly eighteen months time. This paper

attempts to throw some light on the state of financial sector regulation in India,

how it survived the 2008 credit crisis and what needs to be done to meet the

challenge of financing infrastructure competitively.

2. An overview of Financial Sector Regulations and Competitiveness

Scenario

Soon after the 2008 credit crisis broke out, the President of the UN General

Assembly established a UN commission on the global crisis under the

1

This article was written for the India Competition and Regulation Report, 2011, to be published by CUTS

International, New Delhi which holds copyright of the paper.

2

The Savings and Lending companies were bailed out in 1987, Long-Term Capital Management was bailed

out in September 1998 by the Federal Reserve in the US and Northern Rock was nationalized in February

2008 in the UK.

2/21

Chairmanship of Professor Joseph Stieglitz to study its impact on the developing

countries (Reddy, 2011). The commission did not have teeth to implement its

suggestions but its findings rationalized the importance of financial sector for a

developing country and the role of public policy in a developing country to

develop its financial sector. Needless to say that the commission was to take

heads-on the Washington consensus of the role of financial sector in the world

economy in general and the role of capital account convertibility in particular.

The UN commission recognized two paramount reasons to implement good

regulations in the financial sector. First, the regulations to protect consumers

and investors who are considered unsophisticated and whose savings are in the

custody of the financial system. Second, failure of financial firms leads to

severely limit trust and confidence among economic agents. The authorities

should take cognizance of empirical evidence that there will be attempts to avoid

regulations; but this should not be the basis for diluting appropriate and effective

regulations. Moreover, regulations should be made to ensure that all bank like

entities whether they are called a bank or not should be regulated such that

peoples trust in such institutions remains intact. Even intermediaries which

serve financial sectors such as credit rating agencies should also be regulated.

Under the paradigm of market based economy, the central banks and financial

regulators believed that the financial markets would ensure a smooth correction

of mis-pricing of risks by themselves. After the 2008 crisis, such trust placed by

the central banks in financial markets seems to have been misplaced.

It is widely believed there was a regulatory capture by the financial institutions

3

.

The post-crisis inquiries suggest that the market participants had grown so big in

size, wealth, income and influence than the non-financial sector that they

exercised a strong influence on opinion making including through the media.

A recent documentary movie, written and directed by Charles Ferguson, titled

Inside Job has severely damaged the reputation of financial economists,

regulators, teachers of business schools and financial institutions in general. The

film argues that the global economic crisis arose from a few hundred individual

acts of uncontaminated self-interest which led to deregulation. These individuals

earned enormous amount of money at the expense of general public at large and

put to risk their jobs, savings, houses and pensions. The film depicts that there

was a thin line between legality and outright fraud.

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) of the US was established in 2009

to ask and answer this central question: how did it come to pass that in 2008 our

nation was forced to choose between two stark and painful alternativeseither

risk the total collapse of our financial system and economy or inject trillions of

taxpayer dollars into the financial system and an array of companies, as millions

of Americans still lost their jobs, their savings, and their homes?. The

Commission found that it was the collapse of the housing bubble fueled by low

interest rates, easy credit, scant regulation and toxic mortgages which sparked

3

The regulatory capture implies persuading or gently forcing the regulator by the regulated to do what is

favourable to the regulated, essentially based on an information asymmetry because the regulated tend to

have more and better information on relevant aspects than regulators.

3/21

the crisis in 2008. The crisis could be avoided if the Federal Reserve had

stopped the flow of toxic mortgages by setting prudent mortgage-lending

standard. The failures in financial regulation and supervision proved devastating

to the stability of the financial markets. The supervision failed because

government allowed financial firms to choose their regulator and they chose the

weakest one. Further, there was a failure of corporate governance and systemic

failure of risk management. The firms took excessive risk with too little capital

and with too much dependence on short-term funding. Moreover, the leverage

was often hidden in OTC derivatives position, in off-balance sheet entities and

through window dressing of financial reports (FCIC, 2011). The Commission

found that there was a systemic breakdown in accountability and ethics and OTC

derivatives contributed significantly to the crisis. The commission also found the

credit rating agencies to be equally responsible as they gave their seal of

approval blindly without understanding mortgage related derivatives of

derivatives. The Commission concluded that they found dramatic breakdown of

corporate governance, profound lapses in regulatory oversight, and near fatal

flaws in our financial system.

The FCIC findings are not very different from the documentary film Inside Job.

The subprime crisis has an important bearing on the design of regulatory system

not only in the US but all over the world because pursuit of self-interest in the

absence of moral integrity is harming fortune of innocent millions4. In the US the

multiplicity of regulatory authorities are blamed for the crisis as they complicated

the issues of jurisdiction. In the UK, where there was the single regulator the

Financial Services Authority could not anticipate the extent of latent risk. Leave

aside quantification, even the identification of risks associated with the

widespread diffusion of derivative products seemed beyond the capabilities of the

regulatory authorities. Moreover, risk management models which could capture

macroeconomic risks emanating from interest rates or exchange rate were

unable to endogenise systemic risk or liquidity risk.

The FCIC found that just prior to the crisis, there was an explosion in risky

subprime lending and securitization, an unsustainable rise in housing prices,

widespread reports of egregious lending practices, a dramatic increase in

household mortgage debt and an exponential growth in unregulated derivatives,

among many other red flags. The commission also identified widespread failures

in financial regulation, corporate governance and risk management, lack of

transparency, and a systematic breakdown in accountability and ethics as key

causes of the crisis

There are protagonists who still believe that free market, if left by itself, is able to

take corrective steps on its own. According to Alan Greenspan, former Chairman

4

Adam Smith referred to the advantages of an economic system based on self-interest of

individuals. I presume that he had in mind individuals who had a moral fiber akin to that

described in his Theory of Moral Sentiments. The Theory discusses concepts like propriety, the

foundation of judgments concerning our sentiments and conduct, the sense of duty, character of

virtue and systems of moral philosophy.

4/21

of the Federal Reserve, things went well over the long period of deregulation and

light-touch oversight, and he argues that the global financial system is now so

unredeemably opaque that policymakers and legislators cannot hope to

address its complexity (Frank, 2011). However, both his predecessor and

successor as chairman of the Federal Reserve called for substantial changes

and helped to shape the new rules.

A sharply critical report from the Internationally Monetary Funds (IMF)

independent evaluation office pointed out that the IMF was very late to spot

the severe interconnected problems in the worlds advanced economies. As late

as the summer of 2008, the IMFs management was confident that the US has

avoided a hard landing and the worst news are [sic] behind us (Beattie, 2011).

The FCIC findings, the IMFs independent evaluation office and FSA in the UK

are agreeing to have higher risk weighted capital, control over capital flows,

financials sector being subservient to real economy and reduction in OTC

derivative products.

It is believed that the new Basel III capital standards and the ability of regulators

to insist on even greater capital will ensure more prudent and productive lending.

Financial institutions in the developed world have raised alarms and loss of

competitiveness due to new capital adequacy norms as credit supply must rise

by more than $100,000bn in the next 10 years double of its current levels to

meet demand for new funding worldwide. S&P has estimated that public and

private sector borrowers worldwide will need to raise or refinance about

$70,000bn of bonds between now and the end of 2015. (Sharma, 2011)

The Basel III rules prescribing higher standards for assessing risks and stricter

capital requirements come in the wake of the credit crisis that pushed the world

into recession. Written by the Bank of International Settlements, the rules are due

for implementation from 2013. The Basel liquidity proposals, according to the

financial institutions, could undermine banks ability to provide services such as

backup credit lines as well as funding for international trade and retail borrowers

(ET, 2011a). Therefore, the head of the Financial Services Authority has called

for a radical rethink of consumer protection in the UK, including the possible

imposition of fee caps and bans on some retail financial products (Masters,

2011).

The FSA is not the only regulator trying to tighten rules. The US has established

a consumer bureau to oversee mortgages and credit cards, while the Securities

and Exchange Commission recommended that brokers be required to act in the

best interest of their customers. In the UK, regulators have begun shifting to

more intrusive supervision of financial products. The FSA now asks more

questions when companies record large gross margins on the sale of a particular

product, and is also increasing scrutiny of bundled products and sales of related-

party investment products by financial advisers.

5/21

3. Indian Scenario : A Comparative Perspective vis--vis the Global

Best Practices

The main regulators of the financial sector in India are the Reserve Bank of India

(RBI), the Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the Forward Market

Commission (FMC), the Insurance Regulation and Development Authority

(IRDA), the Pension Fund Regulation and Development Authority (PFRDA) and

the Ministry of Finance (MoF). They regulate money, securities, commodities,

insurance markets and pension funds in India. All of them have been established

by an act of parliament and report to the Ministry of Finance except the FMC.

The MoF is the policy making body of the financial sector in India and the

Department of Consumer Affairs is for the commodities market. In principle, all

regulators are to maintain a free and fair market, maintain price stability and

protect the small investor.

The Reserve Bank of India, the central bank, does not have a formal mandate to

maintain financial stability in the country but the bank has interpreted its mandate

on monetary stability to include both price and financial stability. The way

forward for financial sector regulation in India is three fold: to maintain

macroeconomic stability, the growth of domestic financial system and to manage

integration of domestic financial system with that of the international financial

system.

It is difficult to pin-point what has led Indian regulators to be conservative and

cautious in financial regulation. However, the Asian financial crisis of 1997 left

an indelible impression on their minds. The Asian financial crisis was linked to

foreign capital and foreign exchange markets destabilizing the domestic markets.

The Raghuram Rajan report, however, comments that it is not the foreign capital

but the poor governance, poor risk management, asset liability mismatches,

inadequate disclosure, excessive related party transactions and murky

bankruptcy laws that make an economic system prone to crisis (GoI, 2009).

Before we go over to the question of learning from the 2008 credit crisis, it would

be appropriate to highlight the salient features of the Indian financial sector. A

large population of India lives close to the poverty line and their well being is

extremely sensitive to inflation. Price stability forms overarching goal of financial

sector regulation. Incidentally, the price stability is also conducive to investment.

Hence, the underlying belief that policy makers carry with them is that the health

of the financial sector is contingent upon prospects in the real sector. This

perspective has resulted in a cautious gradualist approach to financial

liberalization and deregulation in the past three decades.

Indian banks continue to remain well capitalized. In March 2009, common equity

accounted for 7% of risk capital against the norm of 3-4% for most of

international banks. Tier 1 capital reserves were 13.75% against 9.4% for large

multinational banks. Thus leverage ratio was only 17. Indian banks, accused of

over-capitalization earlier, were well equipped to deal with the initial losses as

some borrowers started to default when the 2008 credit crisis hit the market.

More than 2/3

rd

of banks are state owned and though rupee is fully convertible on

the current account, it is partially convertible on the capital account. Thus, a

6/21

major channel of transmission of financial instability does not exist. The

convertibility restrictions keep the debt markets, especially the sovereign debt

market insulated from global financial markets. This provides strength to the

monetary policy to operate with relative independence and limits contagion

effects and moderates the adverse effects of the global crisis.

The smaller size of Indian banks coupled with non-convertibility of rupee on

capital account did not permit banks to enter into complex derivative transactions

in international markets. Their size and local presence forced them to operate in

domestic market rather than develop international expertise to operate in

international operations. The central banks perspective of the financial sector,

on the other hand, ensures that a pre-emptive counter-cyclical monetary policy is

followed to mitigate the effects of the business cycle by raising risk weights and

tightening the provisions against loans to sectors with rapid credit growth be it

housing sector, mutual funds or capital markets. The pre-emptive steps remove

incentives to the under pricing of risk. Additionally, monetary policy is used in

tandem for macro-prudential measures.

According to the Raghuram Rajan report, the last two decades of reforms have

created a robust regulatory framework but it is insufficient for a growing Indian

economy now and India must recognize that there are some deficiencies in the

current regulatory system which needs to be put right now.

The Indian economy reached its pre-crisis level in less than eighteen months

time and economic growth rate in 2009-10 and 2010-11 was 7.4% and 7.5%.

Therefore, there is little doubt that India emerged stronger, more resilient and self

confident after the crisis

5

(see Appendix 3). It is difficult to say what would have

happened if the crisis had occurred after India had allowed full capital account

convertibility. At least now, the macro-balances that were judiciously maintained

and doggedness with which the financial sector was not allowed to outgrow the

real sector, have earned appreciation globally.

According to Y.V. Reddy, the former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India,

India has been less affected by the crisis than most other countries

6

. Of the

several reasons responsible for this, the most important have been the

avoidance of macroeconomic imbalances; more active countercyclical policies in

the monetary and financial sectors; and a moderate integration with the global

economy. The policy response was also prompt and effective. A well-thought-

out use of a range of policy instruments already put in place during the boom

years helped to effectively manage the crisis (Reddy, 2011). Dr Reddy has

gone on to argue that the impact of the 2008 credit crisis was less than the

shrinkage in GDP growth rate observed in 2008 and 2009 because in 2007 the

economy was showing signs of overheating and some cyclical correction was to

be expected in 2008. If that cyclical correction is taken into account, the

5

See growth rates of BRIC countries in Appendix 3 which support Dr Y.V.Reddys claim in spite of euro-

crisis.

6

The comparison shows that growth rate of all the BRIC countries were hit by the crisis in 2009 but India

suffered much less. Rebound in all the economies occurred in 2010 but were not able to maintain growth

momentum in 2011 except that in India

7/21

slowdown in economy which can be attributed to the 2008 credit crisis will be

even less than the contraction recorded in the GDP figures of 2008 and 2009.

SEBI

The objectives of the Securities Exchange Board of India are to develop the

securities market and to promote investors interest. To fulfill its objectives it

makes rules and regulations for the securities market.

In the past two decades of its existence, SEBI has achieved a securities market,

which is modern in infrastructure and follows international best practices. The

markets are efficient, safe, investor friendly and globally competitive. SEBI has

been in the forefront of protecting interest of minority share holders. Small

investors have benefited from improved market transparency, quarterly

disclosure standards, monitoring of corporate governance and enhancement of

the market safety through an efficient margin system and stepping up of

surveillance. SEBI is quite active in solving investor grievances issues promptly.

Role of Competition Commission of India

As markets are becoming competitive in different sectors, the underlying belief is

that with easy conditions of entry and exit, and open access to networks, the

markets would provide sufficient constraints on the behavior of service providers.

Demand would be responsive to supply cost. Information transparency

empowers consumers to make inter-company comparisons or measure

performance over time and thus, put pressure on companies to improve

performance. Adequate standards exist for Quality of Supply and Service along

with reliable systems for monitoring and enforcing them. Therefore, regulators

need not be involved in detailed price controls or choice of technology. In certain

sectors, the impact of competition on prices of services is palpable and in others

the gradual change hides away the underlying competitive forces. In a

competition led scenario where competition emerges as a reliable and effective

means of regulation, protection of consumer interest, and driving user charges

towards marginal costs, the Competition Commission of India could play a bigger

role than sector specific regulatory authorities.

The Competition Commission of India having economy wide mandate

encourages competition in real sector as well as the financial sector. Within the

real sector it is the market penetration (measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman

Index, a commonly accepted measure of market concentration). In the

infrastructure sector, where due to network effect local monopoly exists, the CCI

could also provide an oversight in the monitoring of contracts. The manner in

which contracts are implemented can result in competition issues that can

include abuse of dominant position or anti competitive agreements on the basis

of the rights vested under the concession agreement. The CCI can, in such

situations, examine the manner in which the contract is being implemented.

8/21

The issues related to financial sector have started coming up recently. SEBI has

detailed guidelines on the mergers and acquisitions of listed companies to

protect interest of minority shareholders. These norms are going to be tested

against the merger control provisions of the Competition Act, 2002, when they

become effective from June 1, 2011.

From the draft regulations, it appears that the procedure for acquisition of shares

or voting rights of listed companies in the country will undergo a substantial

change from June 2011. The new regulation will impact all combinations that

meet the prescribed threshold for India or worldwide assets or turnover of the

target company and the India or worldwide assets or turnover of the parties to the

acquisition or the group to which the target would belong after the acquisition.

There seems to be a divergence when it comes to the operative provisions. The

Competition Act states that any person who proposes to enter into a combination

shall give notice to the commission in the relevant form within 30 days of

execution of any agreement or other document for acquisition.

Given that the SEBI Takeover Regulations are also due to undergo a substantial

change, it is still early days to predict how acquisition of listed companies will be

regulated because jurisdiction of CCI and SEBI are overlapping. (Shroff and

Khan, 2011)

Indian perspective on financial sector reforms

In the last decade the GoI has tried with mixed results to carry out reforms in the

financial sector in the country. A committee of bankers, investment bankers and

stock exchanges submitted their report in 2007 known as the High Powered

Expert Committee on Making Mumbai an International Financial Centre (also

known as the Percy Committee) (MoF, 2007). The Percy Committee was in

favour of liberalizing the financial sector as much as the leading financial centres

of the world such as London and New York. It was in favour of adopting light

handed regulatory regime.

Another committee on financial sector reforms was constituted under the

Chairmanship of Raghuram Rajan to identify the emerging challenges in meeting

the financing needs of the Indian economy in the coming decade and to identify

real sector reforms that would allow those needs to be more easily met by the

financial sector in August 2007. The Committee had wider representation than

the Percy Committee and compared to the Percy Committee had wider mandate.

The Committee submitted its report in September 2008, i.e. soon after the credit

crisis of 2008 had almost brought down the financial system of the world to its

knees. The Committee made 35 recommendations (Appendix -1). The

proposals are a mixture of micro and macro level reforms for the banking,

securities and non-banking financial sector. According to the Raghuram Rajan

Committee the guiding principle of the financial sector reforms in India should be

to include more Indians in the growth process; to foster growth itself and to

protect the Indian economy from financial market bubble which afflicted

developed world in 2008 (GOI, 2009). Another guiding principle for the

Committee was to recognize that efficiency, innovation and value for money are

9/21

as important for the poor as they are for emerging Indian multinationals, and

these will come from deregulation, new entry and competition in the sector.

Since 2008, the recommendations made by the Raghuram Rajan Committee

have been the guiding reforms in the financial sector in India.

The regulatory philosophy followed by the central bank in the past in India was

that innovations in the financial sector should serve the needs of the real sector.

This philosophy in the financial sector avoided a significant build-up of asset

price bubble before the financial crisis caused by the global liquidity in 2008. The

high macro-prudential measures helped in maintaining the health of the

banking system when credit crisis came in 2008.

Another feature of our financial system which makes us less globalized and

sophisticated also leads us to being less susceptible to contagion effects.

Besides this the central bank took measures to counteract the ripple effects after

the crisis occurred

7

.

After the crisis, inquiries carried out by the US Congress, the IMFs independent

evaluation office and the UN Commission have not only endorsed this philosophy

but have strongly recommended the Basle III capital adequacy norms and re-

regulate the sector to serve the needs of the real sector. This implies that SME

would get credit at a reasonable rate of interest while maintaining price stability.

The issue of credit needs of tiny sector, until recently met by unorganized sector,

is being brought into the purview of the central bank in line with the

recommendation of the Raghuram Rajan Committee (Recommendations 6 and

29: Appendix 1).

The Raghuram Rajan committee which went into the details of financial sector

reforms started its work with the premise that Indian financial sector needs to

reach out to small enterprises, those people who are outside the ambit of the

banking sector. The government is following the blue print provided by the

Committee. The Committee has recommended a gradual approach to financial

sector reform rather than a big bang approach. Financial sector regulations

wedded to meet the needs of the real economy carried out gradually will help

financial inclusion. Not only that, governments poverty alleviation schemes such

as MGNREGA will have payment component delivered through the banking

sector. Other centrally sponsored schemes such as pension and insurance are

also going to be delivered through the banking network and that would ensure

financial inclusion.

The GoI established a Financial Stability Development Council to engage in

macro prudential supervision of the economy, including the functioning of large

financial conglomerates and address inter-regulatory coordination issues.

However, doubts have been raised that the constituent regulators such as RBI

will lose some of their regulatory powers and the possibility of dilution of their

accountability (Patil, 2010).

7

I am thankful to an unknown reviewer for expanding the philosophy very succinctly.

10/21

Establishing one regulator for the financial sector has been opposed by the

existing regulators of financial markets and the Raghuram Rajan committee also

has suggested that India is not ready for a single super regulator in India.

Collating central banking regulation with the capital markets regulation is a non-

starter. Regulators and regulated have to reconcile to such multiple domain

suzerainty and learn to consult, cooperate and coexist in a harmonious manner

such that no unsolvable inconsistencies creep in. The whole process put

enormous burden of compliance on the regulated entities. In India, there exists

strong representation of regulatory membership on boards and other decision

making bodies; hence, practical conventions should be developed regarding

which of the regulators in particular circumstances work as the first among

equals and defer to their wisdom and domain. Government of the day, then,

should leave the regulators to carry on with their job (Balasubramanian et. al.,

2010). The time-tested method of diffusion of authority and a well-functioning

system of checks and balances overseen by an independent judiciary is probably

the best bet to ensure regulatory maturity, independence, and constraint.

The FCIC in the US found enough evidence that firms have strong short-term

incentives to avoid and even evade regulation which threaten to limit their profits.

Hence, the success of regulation depends on compliance rather than having just

the rule book.

One of the recommendations of the Raghuram Rajan committee is to rewrite

financial sector regulation (Recommendation 20 : Appendix 1). The government

has appointed a retired Supreme Court judge B.N Srikrishna as the Chairman of

the Financial Sector Legislative Reform Commission. According to him the case

for a super-regulator becomes strong as the boundary lines for most financial

products getting blurred. The commission is going to appoint sub-committees

and identify key areas for research and come out with concept paper. The full

commission will debate on the issues. The concept paper is going to be written

after due consultation with industry associations and stock exchanges (ET,

2011b).

One of the driving forces in the financial sector reform in India is to provide

financial resources for construction of infrastructure sector in India. It is widely

believed that physical infrastructure supports economic growth. For the reasons

of prudent fiscal policy, GoI is not keen to fund infrastructure sector using tax

payers money and encourages private sector to raise funds from domestic and

international markets to fund infrastructure. The responsibility to provide

infrastructure sector services such as roads, ports, railways, airports, electricity

and water would always remain with the government, and the private sector can

only be responsible for construction, operation and maintenance of these

services.

4. Infrastructure Financing Regulations in India

Until 1990, the provider of capital and services for infrastructure in India was

government. With prospects of weak commercialization, low levels of public

investment, rationing, shortage, and poor quality becoming evident, economic

11/21

reforms were initiated in these sectors to encourage private sector participation

(PSP). The aim of PSPs was to attract private capital and management skills in

infrastructure provisioning and service delivery. Due to monopolistic nature of

infrastructure services, there were concerns that transfer of rights to provide

infrastructure services from public to private sector may result in either under-

provisioning of services to some segments of society by the private sector or

private sector may charge higher prices well above the cost of providing such

services. At the same time, PSP would not materialize without enabling legal,

policy and regulatory frameworks that address risks of administrative

expropriation ex-post i.e. after the private sector investment has come through. If

the private sector perceives expropriation risk to be too high, they will either

demand a very high risk premium or they would not invest at all.

The infrastructure projects generally are highly leveraged. In the next few years,

capital markets will need to make an even bigger contribution to supporting

growth, building infrastructure, and creating jobs worldwide. Nurturing their

development as transparent, well-governed and liquid sources of funding must

be a policy priority. Therefore, deregulation of debt market has become

important. However, that would also mean that the central bank would have

lesser control on one of the policy levers as explained in section 3. Given the

financial needs of the infrastructure sector, government is bringing forth reforms

in the financial sector to meet its capital needs.

a. Key concerns of private financing for infrastructure

India faces significant challenges if the $1 trillion infrastructure investment

requirement over the 12th five year plan (FYP)

8

period is to be met. Success in

attracting private funding for infrastructure will depend on Indias ability to

develop a financial sector which can provide a diversified set of instruments for

investors and issuers to address key risk factors to increasing infrastructure

exposure by project sponsors and financial institutions. Over the last year, while

the central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), introduced regulatory changes

allowing banks to increase their infrastructure exposures, increasing private

investment will require addressing fiscal barriers and procedural inefficiencies

that have contributed to project delays and discouraged private investors. In this

context, while the public sector will remain the key investor in infrastructure, the

public-private partnership (PPP) modality is expected to reduce funding pressure

on the government.

The mid-term appraisal of the 11th FYP (ending FY2012) indicates that the

private sector investment in infrastructure is likely to meet the $150 billion target

by 2012, encouraging the government to target 50% of the planned $1 trillion

infrastructure investment from the private sector during the 12th FYP. Preliminary

estimates suggest that if $500 billion is to come from private sector and

assuming a 7030 debt equity ratio, India would need around $150 billion of

equity and $350 billion of debt over a period of five years or around $70 billion of

8

Ending FY2017.

12/21

debt a year. In light of the large debt requirements, India does not have a

sufficiently active debt market where the predominant providers are banks.

Banks are not designed to provide long-term loans required by infrastructure

projects, as they have short-term deposits and can develop asset liability

management (ALM) mismatches as a consequence of providing long-term

financing. In developed markets, long-term debt is provided by corporate bonds

and thus, the development of the corporate debt market is a key element in

financial sector reforms in India.

While government policies support the PPP modality to meet the infrastructure

deficit, PPPs also represent a claim on public resources. PPP transactions are

often complex, needing clear specifications of the services to be provided and an

understanding of the way risks are allocated between the public and private

sector. Their long-term nature implies that the government has to develop and

manage a relationship with the private providers to overcome unexpected events

that can disrupt even well-designed contracts. Thus, financiers need to manage

long-term risk, given potential for delays in commissioning projects and risks due

to market factors post commercial operation date (COD) (WB, 2006).

b. Can regulatory changes/policies alleviate these problems

Regulatory limits. As Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCB) play an important

role in infrastructure financing, regulatory limits on bank investments in corporate

bonds have been relaxed to 20% of total non-statutory liquidity ratio (SLR)

investments. As per revised norms, credit exposure to single borrower has been

raised to 20% of bank capital, provided the additional exposure is to

infrastructure, and group exposure has also been raised to 50% provided the

incremental exposure is for infrastructure.

9

As a consequence of revised norms,

bank exposure to infrastructure has grown by over 3.7 times between March

2005 and 2009.

With regard to SCB exposures to non-banking finance companies (NBFCs), the

lending and investment, including off balance sheet, exposures of a SCB to a

single NBFC/NBFC Asset Financing Company (AFC) may not exceed 10%

and/or 15% respectively, of the SCBs audited capital funds. However, SCBs

may assume exposures on a single NBFC/NBFC-AFC up to 15% and/or 20%

respectively, of their capital funds, if the incremental exposure is on account of

funds on-lent by the NBFC/NBFC-AFC to infrastructure. Further, exposures of a

bank to infrastructure finance companies (IFCs) should not exceed 15% of its

capital funds as per its last audited balance sheet, with a provision to increase it

to 20% if the same is on account of funds on-lent by the IFCs to infrastructure.

10

To ensure that equity appreciation of sponsors in infrastructure special purpose

vehicles (SPVs) can finance other infrastructure projects, the government has

9

The definition of infrastructure lending and the list of items included under infrastructure sector are as per

the RBIs definition of infrastructure (Annexure 2).

10

Reserve Bank of Indias Master Circular on Exposure Norms issued on July 1, 2010 (RBI/2010-11/68,

DBOD No.Dir.BC.14/13.03.00/2010-11).

13/21

substituted the word substantial in place of wholly in section 10(23G) of the

Income Tax Act 1961. This change will provide operational flexibility to

companies that have more than one infrastructure SPV and will allow sponsors to

consolidate their infrastructure SPVs under a single holding company which can

have the critical threshold to carry out a successful public offering. Such a

mechanism will give sponsors and financial intermediaries an exit option from

equity participation which could be recycled for new projects. Given the

overwhelming long-term debt requirements of the infrastructure sector the

following remedial measures are required to develop the debt markets in India.

c. Remedial/ reform measures required to accelerate PPP in

infrastructure

Foreign participation in corporate debt. In January 2009, the government

raised the foreign investment limit in corporate debt to $15 billion from $6 billion.

As of date, foreign exposure in local corporate bonds remains below the $15

billion limit and this limit has been increased to $40 billion now. Higher (FII)

participation will add depth to the market. Secondly, with the essential building

blocks in terms of enabling infrastructure in place, FIIs participation could deepen

longer-tenor (infrastructure) corporate debt market.

Increasing active trading by large domestic participants. Banks should be

persuaded to trade in corporate bonds. This will lead to opening up more

avenues for banks, especially public sector banks, to actively trade in corporate

bonds, which will increase turnover in the secondary market and add to the

liquidity and depth in the market.

Regulatory Reforms

The RBI has taken steps to help the development of the government securities

and corporate bond markets. The gradual extinguishing of illiquid, infrequently

traded bonds, and re-issue of liquid bonds has helped in improving liquidity in

government securities and issue of long-dated bonds has helped in lengthening

the reference yield curve. Compulsory announcement of government market

deals has provided transparency. However, products such as interest rate futures

have not taken off as long-term investors such as insurance and pension funds

are not allowed to operate in this market.

Regulatory reforms which will help in providing liquidity in the debt markets are:

(i) Regulations require pension and insurance funds to hold all

government securities until maturity. This regulation restricts trading

and hampers liquidity and depth to the secondary debt market.

(ii) IRDA requires insurance companies to invest in debt paper with a

minimum credit rating of AA, which automatically excludes

investment by insurance companies in debt paper of most private

infrastructure sponsors. Credit enhancement products can help in

14/21

regulatory concerns as well as attracting long-term funds to

infrastructure sector.

(iii) While exposure limits of banks to Non-Banking Finance Companies

(NBFCs) and Infrastructure Finance Companies (IFCs) have been

relaxed, a large part of it will be taken up by the existing working

capital requirements. Going forward, pension and insurance funds

may be permitted to deposit part of their long-term funds with banks

for infrastructure financing.

(iv) To encourage investment in infrastructure assets and to de-risk

financial sector balance sheet, investment in SEBI- registered debt

funds may be treated on par with direct exposures like direct bonds

and debentures, and not subject to limits.

(v) RBI may gradually relax limits placed on FIIs in long-term corporate

bonds and securitized products allowing debt funds to invest in units

of debt/fixed income mutual funds and in SEBI registered private debt

funds.

5. Conclusion

An important lesson for India from the subprime crisis is that the national

regulatory structure has a much stronger impact in mitigating the effects of the

crisis than a banks governance structure. A small part of Indian banking sector

which took the hit from the subprime crisis illustrates that the banks governance

structure of these banks was no different from their counterparts in the developed

world.

Some of the analysts in India and abroad have commented on Indias daft

handling of the credit crisis pointing out to Indias comparative underdeveloped

nature of the financial sector and in particular, conservative stand taken by the

central bank. The Former RBI Governor Y.V. Reddy refutes this misplaced

belief. According to him, India was active in policy interventions in both,

monetary and financial sectors. The RBI adopted an active countercyclical policy

unlike other central banks, which failed to intervene (Reddy, 2011). Hence,

these policies need to be pursued as appropriate to evolving circumstances.

Notwithstanding the success of the past policy interventions, India cannot afford

to maintain status quo in the financial sector as the Indian financial system has

many inadequacies, spanning from an inappropriate credit culture to financial

exclusion and poor service. He is confident that India can weather a similar

credit crisis but the financial sector needs to develop further to meet the

demands of the real sector. These needs can be met only when there are

synchronized reforms in both, real and financial sectors.

Keeping government debt market strictly controlled is something which the

successive governments and RBI governors have espoused but no policy

document has ever mentioned it publically. Reddy (2011) enumerates this latent

policy maxim in the following way The proven resilience of the Indian economy

and the anticipated bright prospects for growth may whet the appetite for Indian

15/21

government securities in international financial markets. This will increase the

pressure on government by global financial markets for greater access to the

public debt of India. If India gives in to such pressures, it would undermine an

important policy source of stability in Indian debt markets. The lessons of

Greece should not be ignored in haste.

It is critical, however, to note that infrastructure investment requires significant

dedication of time, organizational resources, and management focus. To meet

capital needs of the infrastructure sector, government is willing to open debt

markets in India. The RBI has taken several steps to make the debt market

liquid and increase the FII participation in it. The RBIs steps are gradual and

with deferred time frame keeping up with its philosophy that financial sector

should serve the growing needs of the real sector.

Merger control provisions of the Competition Act, 2002, are now set to be

effective from June 1, 2011. The merger control provisions of the Act give the

CCI the power to review qualifying transactions before they close, to see whether

they might cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition. (Shroff and

Khan, 2011)

The state of financial sector regulation in India is evolving at a gradual pace and

there is no evidence of regulatory capture. We are hopeful that financial sector

reforms carried out in tandem with the real sector would be beneficial to millions

of people who, at present, fall outside the periphery of Indian financial system.

16/21

References

Balasubramanian N. and D.M. Satwalekar (editors) ( 2010) Corporate

Governance : An Emerging Scenario, National Stock

Exchange of India Ltd., Mumbai (NSE)

Beattie Alan (2011) Watchdog says IMF missed crisis risks, Financial Times,

London, February 9, 2011

ET (2011a) Bankers Inc Flags Risk of Regulatory Overkill, Economic Times,

March 5, 2011

ET (2011b) FSLRC to Decide on RBIs Bank Licensing Powers, Economic

Times, March 31, 2011

FCIC (2011) The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, The Financial Crisis Inquiry

Commission, The United States, Washington

FSA (2011) - Product Intervention, Discussion Paper DP11/1, Financial Services

Authority, London, UK

Frank Barney (2011) Greenspan is wrong : we can reform finance, Financial

Times, London, April 3, 2011

GOI (2009) - A Hundred Small Steps, Report of the Committee on Financial

Sector Reforms, Planning Commission, New Delhi, India

(Also known as the Raghuram Rajan Committee Report)

Masters Brooke (2011) FSA chief seeks new consumer safeguards, Financial

Times, London, January 24, 2011

MoF (2007) - Report of the High Powered Expert Committee on Making Mumbai

an International Financial Centre, Ministry of Finance,

Government of India, New Delhi (Also known as Percy

Mistry Committee Report)

Patil R. H. (2010) Financial Sector Reforms : Realities and Myths, Economic

and Political Weekly (8 May 2010), 45(19).

Reddy Y.V.(2011) Global Crisis Recession and Uneven Recovery, Orient

Blackswan Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India

Sharma Deven (2011) Reforms need to nurture capital markets, Financial

Times, London, January 26, 2011

Shroff P. and Khan P. (2011) Case of Regulatory Overreach, Economic Times,

March 31, 2011

WB (2006) - India: Addressing Supply Side Constraints to Infrastructure

Financing. The World Bank, Washington, D.C

17/21

Annexure 1

Proposals made by the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms (The

Raghuram Rajan Committee Report)

1. The RBI should formally have a single objective, to stay close to a low

inflation number, or within a range, in the medium term, and move steadily

to a single instrument, the short-term interest rate (repo and reverse repo)

to achieve it.

2. Steadily open up investment in the rupee corporate and government bond

markets to foreign investors after a clear monetary policy framework is in

place.

3. Allow more entry to private well-governed deposit-taking small finance

banks

4. Liberalize the banking correspondent regulation so that a wide range of

local agents can serve to extend financial services. Use technology both

to reduce costs and to limit fraud and misrepresentation.

5. Offer priority sector loan certificates (PSLC) to all entities that lend to

eligible categories in the priority sector. Allow banks that undershoot their

priority sector obligations to buy the PSLC and submit it towards fulfillment

of their target.

6. Liberalize the interest rate that institutions can charge, ensuring credit

reaches the poor.

7. Sell small underperforming public sector banks, possibly to another bank

or to a strategic investor, to gain experience with the process and gauge

outcomes.

8. Create stronger boards for large public sector banks, with more power to

outside shareholders (including possibly a private sector strategic

investor), devolving the power to appoint and compensate top executives

to the board.

9. After starting the process of strengthening boards, delink the banks from

additional government oversight, including by the Central Vigilance

Commission and Parliament.

10. Be more liberal in allowing takeovers and mergers, by including

domestically incorporated subsidiaries of foreign banks.

11. Free banks to set up branches and ATMs anywhere.

12. Allow holding company structures, with a parent holding company owning

regulated subsidiaries.

13. Bring all regulation of trading under the Securities and Exchange Board of

India (SEBI).

14. Encourage the introduction of markets that are currently missing such as

exchange traded interest rate and exchange rate derivatives.

15. Stop creating investor uncertainty by banning markets. If market

manipulation is the worry, take direct action against those suspected of

manipulation.

16. Create the concept of one consolidated membership of an exchange for

qualified investors (instead of the current need to obtain memberships for

each product traded).

18/21

17. Encourage the setting up of professional markets and exchanges with a

higher order size, that are restricted to sophisticated investors (based on

net worth and financial knowledge), where more sophisticated products

can be traded.

18. Create a more innovation friendly environment, speeding up the process

by which products are approved by focusing primarily on concerns of

systemic risk, fraud, contract enforcement, transparency and inappropriate

sales practices.

19. Allow greater participation of foreign investors in domestic markets as in

Proposal 2

20. Rewrite financial sector regulation, with only clear objectives and

regulatory principles outlined.

21. Parliament, through the Finance Ministry, and based on expert opinion as

well as the principles enshrined in legislation, should set a specific remit

for each regulator every five years. Every year, each regulator should

report to a standing committee.

22. Regulatory actions should be subject to appeal to the Financial Sector

Appellate Tribunal, which will be set up along the lines of, and subsume,

the Securities Appellate Tribunal.

23. Supervision of all deposit taking institutions must come under the RBI.

Situations where responsibility is shared, such as with the State Registrar

of Cooperative Societies, should gradually cease.

24. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) should review accounts of

unlisted companies, while SEBI should review accounts of listed

companies.

25. A Financial Sector Oversight Agency (FSOA) should be set up by statute.

The FSOAs focus will be both macro-prudential as well as supervisory.

26. The Committee recommends setting up a Working Group on Financial

Sector Reforms with the Finance Minister as the Chairman. The main

focus of this working group would be to marshal financial reforms.

27. Set up an Office of the Financial Ombudsman (OFO), incorporating all

such offices in existing regulators, to serve as an interface between the

household and industry.

28. The Committee recommends strengthening the capacity of the Deposit

Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) to both monitor risk

and resolve a failing bank, instilling a more explicit system of prompt

corrective action, and making deposit insurance premia more risk-based.

29. Expedite the process of creating a unique national ID number with

biometric identification.

30. The Committee recommends movement from a system where information

is shared primarily amongst institutional credit providers on the basis of

reciprocity to a system of subscription.

31. Ongoing efforts to improve land registration and titlingincluding full

cadastral mapping of land, reconciling various registries, forcing

compulsory registration of all land transactions, computerizing land

records, and providing easy remote access to land recordsshould be

expedited.

19/21

32. Restrictions on tenancy should be re-examined so that tenancy can be

formalized in contracts, which can then serve as the basis for borrowing.

33. The power of SRFAESI that are currently conferred only on banks, public

financial institutions, and housing finance companies should be extended

to all institutional lenders.

34. Encourage the entry of more well-capitalized ARCs, including ones with

foreign backing.

35. The Committee outlines a number of desirable attributes of a bankruptcy

code in the Indian context, many of which are aligned with the

recommendations of the Irani Committee. It suggests an expedited move

to legislate the needed amendments to company law.

20/21

ANNEXURE 2 - THE RBIS DEFINITION OF INFRASTRUCTURE LENDING

Any credit facility in whatever form extended by lenders (i.e. banks, FIs or

NBFCs) to an infrastructure facility as specified below falls within the definition of

"infrastructure lending". In other words, a credit facility provided to a borrower

company engaged in:

developing or

operating and maintaining, or

developing, operating and maintaining any infrastructure facility that is

a project in any of the following sectors, or any infrastructure facility of

a similar nature :

i. a road, including toll road, a bridge or a rail system;

ii. a highway project including other activities being an integral part of

the highway project;

iii. a port, airport, inland waterway or inland port;

iv. a water supply project, irrigation project, water treatment system,

sanitation and sewerage system or solid waste management

system;

v. telecommunication services whether basic or cellular, including radio

paging, domestic satellite service (i.e., a satellite owned and

operated by an Indian company for providing telecommunication

service), Telecom Towers network of trunking, broadband network

and internet services;

vi. an industrial park or special economic zone ;

vii. generation or generation and distribution of power including power

projects based on all the renewable energy sources such as wind,

biomass, small hydro, solar, etc.

viii. transmission or distribution of power by laying a network of new

transmission or distribution lines.

ix. construction relating to projects involving agro-processing and

supply of inputs to agriculture;

x. construction for preservation and storage of processed agro-

products, perishable goods such as fruits, vegetables and flowers

including testing facilities for quality;

xi. construction of educational institutions and hospitals.

xii. laying down and / or maintenance of pipelines for gas, crude oil,

petroleum, minerals including city gas distribution networks.

xiii. any other infrastructure facility of similar nature.

Source : RBI

21/21

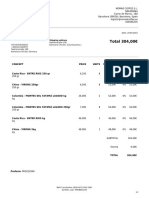

ANNEXURE 3 GROWTH RATES OF BRAZIL, INDIA, CHINA AND SOUTH

KOREA

Brazil India China South Korea

2008 5.1 9.0 13.0 2.2

2009 -0.2 6.7 8.7 0.2

2010 7.5 7.4 10.3 6.1

2011 (est.) 3.0 7.5 9.0 3.5

Note: For India 2009, 2010 and 2011 implies FY 2008-9, 2009-10 and 2010-11 respectively.

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 9NYSE Euronext To Take Over Tainted Libor - ET Dt. 10-07-13Document1 page9NYSE Euronext To Take Over Tainted Libor - ET Dt. 10-07-13Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 5commodity Cycle-April 2013Document3 pages5commodity Cycle-April 2013Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 5indian Bond Market WP Nipfp 2012Document22 pages5indian Bond Market WP Nipfp 2012Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- Debt Funds Are Not As "Safe" As They Sound.: Safety Is Not AssuredDocument5 pagesDebt Funds Are Not As "Safe" As They Sound.: Safety Is Not AssuredRajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 4partnership Enterprise - ET Dt. 05-03-2012Document4 pages4partnership Enterprise - ET Dt. 05-03-2012Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 2will Hit 60 On Worsening Pitch - ET Dt. 12-04-13Document1 page2will Hit 60 On Worsening Pitch - ET Dt. 12-04-13Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 3india Lending Rate April2013 WSJDocument2 pages3india Lending Rate April2013 WSJRajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 4IPO MCX Overbid 54 Imes To Rs.35000 Cr. ET Dt. 25-02-2012Document2 pages4IPO MCX Overbid 54 Imes To Rs.35000 Cr. ET Dt. 25-02-2012Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 2RBI Panel On Mon Pol-WSJ-Jan21-2014Document2 pages2RBI Panel On Mon Pol-WSJ-Jan21-2014Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy Statement For 2013-14 Statement by Dr. D. Subbarao, Governor, Reserve Bank of IndiaDocument5 pagesMonetary Policy Statement For 2013-14 Statement by Dr. D. Subbarao, Governor, Reserve Bank of IndiaRajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 1SBI Hits Global Bond Market To Raise $1 Billion - ET Dt. 12-04-13Document1 page1SBI Hits Global Bond Market To Raise $1 Billion - ET Dt. 12-04-13Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- 2mon Pol-We Dont Want Flip-Flop On Policy Till Inflation Subsides - ET Dt. 26-01-12Document2 pages2mon Pol-We Dont Want Flip-Flop On Policy Till Inflation Subsides - ET Dt. 26-01-12Rajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HBL Internship ReportDocument50 pagesHBL Internship Reportyaqoob008No ratings yet

- External Factor Analysis: Group 4Document14 pagesExternal Factor Analysis: Group 4Abinash BiswalNo ratings yet

- Single Euro Payments Area in SAPDocument12 pagesSingle Euro Payments Area in SAPRicky Das100% (1)

- Finance of International Trade and Related Treasury OperationsDocument2 pagesFinance of International Trade and Related Treasury OperationsmuhammadNo ratings yet

- SBI Clerk Recruitment 2010 - Application FormDocument8 pagesSBI Clerk Recruitment 2010 - Application FormSarbjit SinghNo ratings yet

- MFC 2nd SEMESTER FM Assignment 1 FMDocument6 pagesMFC 2nd SEMESTER FM Assignment 1 FMSumayaNo ratings yet

- MIS and Banking IntroductionDocument5 pagesMIS and Banking IntroductionVaibhav GuptaNo ratings yet

- Rahma Indrawati Selvie Engeline: Data-Data Nasabah Wanita Nama No - Kartu BankDocument144 pagesRahma Indrawati Selvie Engeline: Data-Data Nasabah Wanita Nama No - Kartu BankRachman MercyNo ratings yet

- IA Chapter-1-3Document7 pagesIA Chapter-1-3Christine Joyce EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Project On State Bank of IndiaDocument24 pagesProject On State Bank of Indiamishra anuj61% (38)

- Mobile Money For The UnbankedDocument102 pagesMobile Money For The UnbankedCarlos Alberto TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Day 1 1.1 Session-1 1.2 Banking System in India: AnswersDocument51 pagesDay 1 1.1 Session-1 1.2 Banking System in India: AnswersAkella LokeshNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Non Banking Financial CompaniesDocument17 pagesPresentation On Non Banking Financial CompaniesMayurpmNo ratings yet

- Business Finance: Financial Institutions, Markets, and InstrumentsDocument14 pagesBusiness Finance: Financial Institutions, Markets, and InstrumentsAngelica Paras100% (1)

- 1 LicDocument1 page1 LicAshish BatraNo ratings yet

- E-Banking: Presented by:-PARDEEP KUMAR MBA (Hons.) 2.1 ROLL NO. - 3045Document20 pagesE-Banking: Presented by:-PARDEEP KUMAR MBA (Hons.) 2.1 ROLL NO. - 3045pardeepkayatNo ratings yet

- Money MarketDocument25 pagesMoney MarketUrvashi SinghNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Foreign Exchange Market.Document6 pagesAssignment On Foreign Exchange Market.Sadman Skib.0% (1)

- Adsum Notes Credit Trans FactoidDocument2 pagesAdsum Notes Credit Trans FactoidRaz SPNo ratings yet

- Paschim Gujarat Vij Co. LTD: InvitesDocument5 pagesPaschim Gujarat Vij Co. LTD: Invitesgaurav.shukla360No ratings yet

- Abacus v. AmpilDocument11 pagesAbacus v. AmpilNylaNo ratings yet

- Digital Financial Inclusion andDocument6 pagesDigital Financial Inclusion andInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Money Vocabulary Word ListDocument2 pagesMoney Vocabulary Word ListFehér Imola100% (1)

- ZTBL (New) Internship Report - SalmanDocument44 pagesZTBL (New) Internship Report - SalmanUltimate MemerNo ratings yet

- P2P and O2CDocument59 pagesP2P and O2Cpurnachandra426No ratings yet

- Financial Journalism, News Sources and The Banking Crisis: Paul ManningDocument17 pagesFinancial Journalism, News Sources and The Banking Crisis: Paul ManningmargarethhlrNo ratings yet

- Swissquote-Research 4872bcb4 enDocument14 pagesSwissquote-Research 4872bcb4 enaliffalniNo ratings yet

- F214733 Armin Zandieh Iaro IarocoffeeDocument2 pagesF214733 Armin Zandieh Iaro IarocoffeeCristian CoffeelingNo ratings yet

- Mind Map For FRM I - Part1Document1 pageMind Map For FRM I - Part1api-286576624100% (1)

- Annual Report 2009-10 of Federal BankDocument88 pagesAnnual Report 2009-10 of Federal BankLinda Jacqueline0% (1)