Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FHS Report 07

Uploaded by

The IIHMR University0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

41 views67 pagesHealth, Equity and Poverty Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHealth, Equity and Poverty Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

41 views67 pagesFHS Report 07

Uploaded by

The IIHMR UniversityHealth, Equity and Poverty Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 67

Health, Equity and Poverty

Exploring the Links in West

Bengal, India

Kanjilal B, Mukherjee M, Singh S, Mondal S, Barman D, Mandal A

RESEARCH MONOGRAPH INDIA SERIES

December 2007 www.futurehealthsystems.org

Health, Equity and Poverty

Exploring the Links in West Bengal,

India

FUTUE HE!LTH "#"TE$"

E"E!%H $&'&(!PH

INDIA

Kanjilal B, u!herjee , "ingh ", on#al ", Barman D, an#al A

December 2007

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge and sincerely appreciate the support and inspiration received from the Department of Health and FW,

Government of West Bengal - especially from Dr. Kalyan Bagchi, Additional Chief Secretary (Health & FW). Special thanks

go to Mr. H K Dwivedy, former Special Secretary (Health & FW) for his intense and active interest in the research. The

inspiration received from our colleagues at IIHMR especially from our Director Dr. S D Gupta - is also sincerely appreciated.

Dr. Satish Kumar, Ms. Tannistha Samanta, and Dr. N Ravichandran who were involved at the data collection stage, deserve

special mention.

Primary data from households were collected with active support from Economic Information Technology and KAP two

organizations of Kolkata. The in-charge of various government hospitals fully cooperated with the study team. The key

members of district associations of Rural Medical Practitioners also provided the team with active support.

We also acknowledge the scientific support extended by 'Future Health Systems: Innovations for equity'

( ) a research program consortium of researchers from Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg

School of Public Health (JHSPH), USA; Institute of Development Studies (IDS), UK; Center for Health and Population

Research (ICDDR,B), Bangladesh; Indian Institute of Health Management Research (IIHMR), India; Chinese Health

Economics Institute (CHEI), China; The Institute of Public Health (IPS), Makerere University, Uganda; and University of

Ibadan (UI), College of Medicine, Faculty of Public Health, Nigeria.

We express our appreciation for the financial support (Grant # H050474) provided by the UK Department for International

Development (DFID) for the Future Health Systems research programme consortium. This document is an output from a

project funded by DFID for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID or

Department of Health and FW, Government of West Bengal.

www.futurehealthsystems.org

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

i

Abbreviations

BE Budget Estimates

BPHC Block Primary Health Centre

BPL Below Poverty Line

CI Concentration Index

CMOH Chief Medical Officer, Health

DFID Department for International Development

DH District Hospital

DHF District Health Fund

DHFWS District Health and Family Welfare Society (Samity)

DoHFW Department of Health and Family Welfare

EDL Essential Drug List

FHS Future Health System

FW Family Welfare

GoI Government of India

GoWB Government of West Bengal

HSDI Health System Development Initiative

HMIS Health Management Information System

IEC Information, Education, and Communication

IIHMR Institute of Health Management Research

IPD In-patient Department

JSY Janani Suraksha Yojana (Mother's Protection Scheme)

MCH Maternal and Child Health

rd

NFHS-3 National Family Health Survey (3 round)

NGO Non-government Organization

NSDP Net State Domestic Product

NSSO National Sample Survey Organization

OPD Out-patient Department

OOPE Out of Pocket Expenditure

PER Public Expenditure Review

PHC Primary Health Centre

PMGY Prime Minister's Gramodaya Yojana (rural development scheme)

RCH Reproductive and Child Health

RE Revised Estimates

RH Rural Hospital

RMP Rural Medical Practitioners

SDH Sub-divisional Hospital

SHG Self Help Group

SGH State General Hospital

SHSDP-II State Health System Development Project: Phase Ii

STG Standard Treatment Guideline

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

ii

Preface

This document presents the key results of a recent research on health care system conducted by Institute of Health

Management Research (IIHMR) in West Bengal, India based on a research grant awarded by the Department for International

Development (DFID), United Kingdom to an International Research Programme Consortium (RPC) in which IIHMR is a

partner. The consortium, titled as Future Health Systems: Innovations for Equity (FHS), will carry out innovative research

programmes in six countries. The three basic themes of FHS can be summarized as follows:

How can the poor be protected from the impoverishing impact of health-related shocks?

What innovations with public and private health sector can work for the poor?

How can policy and research processes be used to meet the needs of the poor?

IIHMR has identified West Bengal as the major focus state for implementing the research programme in India. More

specifically, it proposes to explore the potential of the strategy of decentralization of health care services, as manifested in a

series of initiatives recently being spearheaded by the Department of Health and Family Welfare (DoHFW) in the state to

improve the effectiveness of the health system, in protecting interests of poor people.

The guiding principle of the FHS research initiatives in India is putting the poor first supported by the three research themes

mentioned earlier. Hence, the purpose of research is to generate evidences on the link between health, poverty, and consequent

inequity from demand and supply angles and suggest appropriate interventions to weaken the link. Keeping this in mind, the

research in India was planned as a multi-phases initiative. In the first phase, which just completed, a series of scoping studies

were carried out to prepare a knowledge base on which an appropriate strategy for a more equitable health system would be

developed. Phase II, would be devoted to develop a few major proposals, based on the Phase I research results. The proposals

will approach specific interventions at the district level to help the system (1) track resources and benefits from government

subsidies; and (2) protect the poor from health-related financial shocks.

The principle research questions for the Phase I studies were:

1. How does the link between poverty and health manifest itself in the Indian health care market?

2. How much is the supply side environment oriented towards equitable distribution of resources?

3. Whether and to what extent the existing institutional arrangement at the ground level support

implementation and oversight of pro-poor policies?

The studies were carried out at two levels: (1) national and state level, primarily based on available national survey data (NSSO,

RCH Household Survey, etc.); and (2) district level, exclusively based on primary (quantitative and qualitative) data. The

primary data were sourced from three districts of West Bengal (the state selected for the Phase I studies) through rapid

household survey, assessment of selected institutions (such as, health care providers, Panchayet institutions, health

department, autonomous health societies, civil society bodies, and others), and assessment of a few pro-poor schemes (e.g.,

JSY, Rogi Kalyan Samiti, etc.) about whether and to what extent pro-poor policies are implemented.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

iii

The present monograph summarizes the key findings of Phase-I scoping studies which were conducted during January March,

2007. The purpose of disseminating these results is to initiate dialogue between key stakeholders on how to make the health

care delivery system work more for the poor and vulnerable groups of population and protect them from the impoverishing

effects of poor health and consequent health care. Although the data were sourced from a particular state (West Bengal), most

of the findings are expected to be relevant to other Indian states.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

iv

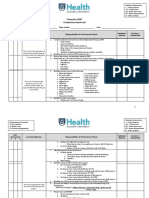

Table of Contents

Section

Title Page

Acknowledgement

Abbreviations

Preface

Executive Summary

i

ii

iii

vi

1 Background

1.1 Introduction 1

1.2 A brief profile of the state 2

1.3 Data and methods 3

2 Health Sector in West Bengal: An overview

2.1 Health status in West Bengal 7

2.2 Health care system in West Bengal 8

2.3 Public financing of health care in West Bengal : an overview 9

2.4 Private health care spending 10

3 Health, Equity and Poverty: Key issues

3.1 Key issues 13

I. Health Care Utilization

3.2 Good performance in ensuring horizontal equity in inpatient care 13

3.3 Young and older women have less access to hospitalization 16

3.4 Government hospitals play dominant role, but without much targeting

3.5 Outpatient care market is dominated by unqualified providers 18

3.6 Strong barriers against equity in institutional delivery 23

3.7 Inequality in utilization of preventive child health care 26

II. Health Care Financing

3.8 Equity in public spending is questionable 28

3.9 Poor oversight at the district level 30

3.10 Medicines and tests: killing fields 31

3.11 OOPE is progressive in inpatient care but not so in outpatient care 34

3.12 Growing health poverty in a socially unprotected environment 36

4 Towards a More Equitable Future : how can research help?

4.1 How to make the system work more for the poor? 43

4.2 Develop a closer working relation with informal sector 43

4.3 Ensure local oversight for implementing pro-poor strategies 45

4.4 Reduce asymmetric information in drugs market 46

4.5 Develop appropriate risk pooling mechanism 47

4.6 Improve targeting in public subsidies for essential health care. 48

4.7 Address the barriers to preventive care and safe birth delivery 51

4.8 Facilitate and regulate private sector 52

References 53

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

v

16

Executive Summary

India is on a fast-track growth path and the health care market is opening up with new opportunities. However,

impressive growth with inadequate social protection may lead to newer vulnerabilities, inequalities, and health

related poverty. The study focused on one Indian state (West Bengal) to explore the link between health, poverty,

and equity against this dynamic backdrop. Primary data - from households and different types of providers - were

collected from three districts of the state.

West Bengal is a middle level achiever in economic front but one of the top rankers (among all major

Indian states) in most of the basic health indicators although the rural areas are significantly behind the urban. The

state has a huge infrastructure of government's health facilities supplemented by an assortment of private health

care providers, which play a minor role in preventive and inpatient care but a major role in ambulatory care.

Despite an impressive growth of public spending on health over the last 15 years, the share of health in total

budget has been declining. Inadequacy of public spending reflects in high out of pocket expenses on health

which is about three times more than the former.

Health, Equity, and Poverty: Key issues

The major findings related to equity and poverty are classified into two groups according to their links to the

following areas: (1) health care utilization, and (2) health care financing.

Health care utilization

Good performance in ensuring horizontal equity in inpatient care: The state has made substantial

progress in ensuring better access and equity in inpatient care. The rate of hospitalization has increased from

1.5% (of total population) in 1995-96 to 4.3% in 2007. The rate is almost uniformly spread across various

socio-economic groups implying a near-perfect horizontal equity in inpatient care.

Young and older women have less access to hospitalization: However, concern remains in gender inequity.

The hospitalization rate was found to be much less for younger and older women than for their corresponding

male counterparts.

Government hospitals play dominant role, but without much targeting: The inpatient care market in

West Bengal is overwhelmingly dominated by public sector an exceptional case since, nationally, private

sector plays the major role. Public hospitals are, however, almost equally used by poor and rich indicating an

uninhibited access to all and missing target mechanism.

Outpatient care market is dominated by unqualified providers: The outpatient care market like other

Indian states is dominated by private providers most of whom practice allopathy without adequate training

(RMPs). The utilization of RMP services in rural areas is almost uniformly spread across various income

groups implying that low cost treatment is not the prime factor to explain people's dependence on RMPs. The

two most important factors, as found, were (1) the average distance to a RMP clinic that was much less than to

a qualified provider; and (2) an attractive packaging of services by RMPs which includes easy availability,

dispensing drugs often on credits, prompt response, and so on.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

vi

Strong barriers against equity in institutional delivery: Perceived benefits (of institutional birth delivery)

are low due to the common belief that birth delivery is a natural process and, hence, it requires no hospitalization.

However, equally important are the barriers (or, cost) to access. Three important barriers are extremely

relevant in this case: (1) long physical distance to the nearest facility, (2) higher out of pocket expenses to seek

birth delivery care from an institution, and (3) poverty. That poverty or economic constraint plays an

important determinant behind choice of place of delivery is evident from the data that 62 percent of all

pregnant mothers in the poorest quintile but only 19 percent of them in the richest quintile delivered at home

clearly implying that barriers get easier as one progresses from poorest to richest quintile.

Inequality in utilization of preventive child health care: There is no significant difference in

immunization rate across gender or rural / urban location, but inequality exists with respect to socio-economic

groups. In other words, poverty is an important dimension to explain the inequity in preventive care. The

scenario is much better in children's curative care where the probability of seeking treatment for a sick child is

more or less same across gender, rural/urban, and socio-economic differential.

Health care financing

Equity in public spending is questionable: During the last few years, the state has made remarkable

progress in pumping additional resources for meeting non-salary and development needs. Yet the

preliminary analysis indicates that there are scopes to improve allocative efficiency of public expenditure.

Major share of public spending goes to urban areas. There are also inequalities in distribution of public

budget across various types of hospitals; for example, the per bed allocation of fund to State General

Hospitals is higher than that to District Hospitals. Demand creation and stewardship two vital functions of

the public sector are allocated little fund. However, despite discrepancies in resource allocation, the state

reflects a reasonably good pro-poor image of policy making on financing. This is quite evident in several

policy decisions improvised during the last few years.

Poor oversight at the district level: It is obvious that for a more effective oversight of public services the

boundary of routine activities should be crossed. However, weak managerial and oversight capacity is one of

the major constraints (at the district level) in this process. The state government has visibly embarked on

several initiatives to arrange more flexible fund and autonomy to the district level. However, there is little

evidence on effective utilization of this autonomy to protect poor from health related financial shock

primarily due to (1) lack of an efficient resource-tracking mechanism, and (2) lack of interest and capacity

among district health administration.

Medicines and test: killing fields: The increase in government's budget on drugs has been significant

especially in the last few years. However, still people spend a substantial amount on drugs even when they

visit government facilities where drugs can be obtained free of cost. The possible reason for this is that about

a half of poor and 70 percent of better-off public clients did not receive some or any drugs from the

government facilities. Dominance of some (i.e., some but not all drugs were available) category offers

several hypotheses about which drugs are not available in government facilities: (1) essential, but prescribed

brands are not available, and (2) non-essential. The hypotheses can be tested only through proper auditing of

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

vii

prescriptions. Another key finding is that a large portion of better-off patients (about 56%) also receives drugs

from government facilities implying that a significant part of drug subsidy is absorbed by those who could

possibly pay for it.

Out of pocket payment is progressive in inpatient care but not so in outpatient care: In case of inpatient

care, the impact of out of pocket payment is relatively more severe on higher income groups indicating a

progressive out of pocket financing system. One out of five households from this group is likely to send at

least one member to hospitals (for inpatient care) which will account for one-sixth of their annual household

expenditure three times more than a normal scenario. The poorest households are likely to send fewer

members, and spend proportionately much less. It is interesting to note that the impact somewhat reverses in

case of outpatient care where poorer households spend more in relative terms. While about 4 percent of

poorest households made catastrophic payments for inpatient care, more than 10 percent did so for outpatient

care.

Growing health poverty in a socially unprotected environment: A framework for analyzing health

poverty is introduced which links vulnerability to health poverty with (i) household entitlements, (ii) supply

side environment, and (iii) perceived opportunity cost of health care. Given that the social entitlement is very

weak, all sections of population depend heavily on individual entitlements income, saving, borrowing, sell of

assets, and so on - when they seek health care. Poorer section was found to depend more on extended

entitlements (e.g., borrowing) implying that health care aggravates their poverty. Supply side environment

was found to have no effective procedure for identifying poor and vulnerable. Opportunity cost of health care

was high for example, 70 percent of households, which sent at least one member to a hospital as an inpatient,

had to reduce their food consumption to pay for the hospital cost.

Towards a More Equitable Future: how can research help?

Develop a closer working relation with informal sector: The study recommends internalizing and using the

huge pool of resources (i.e., RMPs) which is being used by the people anyway. Innovative ways to do so is to (1)

empanel selected RMPs at each block as Rural health gate keepers based on several essential quality indicators.

The role of the RMP will be to provide a set of basic curative services and refer cases immediately to formal

providers as and when the patient crosses the identified safe treatment; (2) identify a set of basic curative and

preventive services for which the RMPs will be given franchise right to operate as official gatekeepers; (3)

involve civil societies (Panchayet or NGO) in implementing empanelment and mentoring the RMPs; and (4)

provide intensive training to selected RMPs on simple treatments, identifying potentially complicated cases and

danger mark where they have to refer. Future research in this area should address the following questions: (1)

how safe or unsafe are the current clinical practices of RMPs? (2) What is the net impact of RMP practices on

rural health? (3) How feasible is it to integrate RMPs into existing public health care system?

Ensure local oversight for implementing pro-poor strategies and resource tracking: Are the resources

meant for poor actually reaching them? The answer may be found only when a mechanism for local oversight is

established. The management unit under DHFWS may be strengthened to initiate resource tracking in the

following areas: (1) delivery of drugs and consumables at government facilities, (2) disbursement of untied funds

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

viii

for special medical assistance to the poor, (3) program funds flowing through the societies, (4) funds generated

through user charges and retained at the district level, and (5) funds from special schemes, such as JSY or PMGY.

Future research in this area may be initiated in the form of a pilot intervention by which the district management

unit may be oriented and its capacity may be built to help it play oversight role.

Reduce asymmetric information in drugs market to empower the consumers: Protection of people from

health poverty necessarily boils down to protecting them from irrational drug expenses. One of the important

factors influencing the irrational process is high degree of asymmetry of information in the medicines market.

Therefore, the ongoing supply side initiatives should be supplemented by demand side interventions based on the

hypothesis that the out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines could be significantly reduced if the consumers are

adequately empowered with information on (1) cheaper (but equally useful) and generic options of prescribed

branded medicines; and (2) a distinction between essential and non-essential medicines in the context of a specific

disease. The empowerment process could be implemented by involving the local level civil societies and local

self-administration (e.g., Panchayet). The process could be initiated after a scoping study on the degree of

asymmetric information in the market, and how the imperfect agents (i.e., providers and pharmacies) are using

this information gap.

Develop appropriate risk pooling mechanism especially for economically disadvantaged section: A district

based health fund is proposed which will be held by DHFWS and operated by a professional insurer. In addition

to subsidy from the government and donors, the fund will be built on prepayment made by the Self-help Groups

(SHG). Premiums will be determined by community-rated ability to pay. Providers will include selected and

accredited private and government hospitals. Only secondary and tertiary government facilities should be

included in the initial stage. Outpatient care should be included in the benefit package. A Technical Resource

Centre will support the quality assurance mechanism and management of information system. Future research in

this area should also be framed as a pilot intervention in one district.

Improve targeting in public subsidies for essential health care: Targeting poor could be done by equitable

distribution of health care services through some sort of rationing by which the richer (including the government

servants) will be able to access within the limit of a fixed quota of subsidized beds. This should be supplemented

with a policy of total withdrawal of subsidy for those facilities that are accessed by the richer section (for example,

private cabins) and recovery of the cost on 100 percent basis. A more gender-sensitized role of providers is

expected to improve the gender inequity in inpatient care. Future research in this area is expected to focus on two

aspects: (1) generating evidences on various targeting mechanisms and assess their feasibility in the context of the

state's health care system, and (2) assessment of the pro-poor schemes initiated by the Department of Health and

FW at the ground level where it works and where it does not.

Address the barriers to preventive care and safe birth delivery: The strong barriers to meet the goals of

universal immunization and safe birth delivery need to be analyzed. For this purpose, the difficult pockets within

the state and within the districts need to be mapped according to the nature of the barrier. Once the under-served

areas are mapped and their barriers are identified, it is necessary to draw up a set of special strategies to cover these

areas. Future research should meet the acute need for scientific information on what and how the barriers lead to

underperformance. It should also help the decision-makers select a cost-effective option to act against those

barriers and test it as a pilot intervention.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

ix

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

x

Facilitate and regulate private sector: Internalization of private sector necessarily implies that the private

sector is to complement, and not just co-exist with, the public sector. The process would require three strategic

steps: (a) Facilitate expansion of private market at those blocks or district headquarters where the government

facilities are over-burdened; (b) minimum standards for its operation need to be maintained and regulated; and (c)

involvement of private sector in district planning process is encouraged. Future research in this area is expected

to provide the policy makers with crucial evidences on the operation of the market and help them design an

effective policy for internalizing the private sector.

1. Background

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

1

1.1. Introduction

1.1.1. Indian economy, by all evidences, is on a fast-track growth path. Economic liberalization, triggered in early 1990s has

taken a sharp upward turn with an impressive growth rate. However, despite India's strong growth performance

which has unleashed enormous potential for economic advancement, there is growing concern that economic

liberalization has been less successful in protecting people from the risk of new vulnerabilities, inequalities, and

insecurities especially in the social sector. Health sector in India epitomizes this proposition. Two patterns are clearly

visible: (1) there is a huge discrepancy in health outcome as well as in health care utilization between rich and poor and

between richer and poorer states. Poor people have worse health, are less entitled to public subsidies, and are less

protected against the financial shock generated by health care.; and (2) due to absence of an effective risk-pooling

mechanism, rising demand for health care and galloping inflation in health care market, even not-so-poor groups of

population are quickly slipping into poverty trap. In other words, India reflects a possible future scenario where the

poverty-reducing impact of economic growth will be countered by poverty-enhancing effects of health care if the

system continues to remain inequitable and people remain largely unprotected against financial risks related to health

shock.

1.1.2. The recent government policies related to health and population implicitly acknowledges the need to address the

question of inequities and vulnerabilities in a more effective way. The best instrument at the government's hand is its

spending on health, which is targeted to increase to 2 percent of GDP by the year 2010 from its current level of 0.9

percent. This would require the states' budgetary allocation on health to rise to 8 percent from its current level of 5-6

percent and the center's contribution to rise from 15 percent to 25 percent (NHP, 2002).

1.1.3. Given the fiscal crisis currently being experienced by the state governments, the target may seem a bit ambitious.

However, a more pertinent question is: will the increased public expenditure ensure better health for poor?

Unfortunately, the present scenario fails to offer an unambiguous answer to the question. The primary reason behind

this ambiguity is gross inequity in the distribution of public health resources. Inequity reflects not only in widening

gap of public spending between poor and rich states (Purfield, 2005), but also in substantial absorption of public

subsidies by the richer people within a given state. As shown by a recent study, about Rs. 3 is received by the richest

quintile for every Re 1 of public health subsidy received by the poorest 20 percent (Peters et al., 2002). The

disproportionate absorption of public subsidies reflects poor targeting in the public health care facilities.

1.1.4. Inadequate public expenditure, coupled with its poor targeting, results in uncontrolled proliferation of private

providers and high out of pocket expenditure by the users of health care. Although government-provided health care

is meant to be heavily subsidized and, as such, to benefit the poor, the majority of health care users who go to public

facilities incur significant out-of-pocket costs. For example, a study in one of the Indian states (West Bengal)

demonstrates that users of public sector facilities pay between 18 percent (for birth delivery) and 72 percent (for major

ailments) of what users of qualified private sector facilities pay for similar services. About 75 percent and 87 percent

of out-of-pocket expenditures in case of treatment of major ailments and minor ailments respectively in public

facilities go towards medicine and diagnostic tests. Most of the users of public hospitals are compelled to purchase

drugs and medicines in the private sector due to shortage of prescribed drugs in hospital pharmacy (Kanjilal and

Pearson, 2002).

1.1.5. Weak targeting mechanism also reflects in heavy skewness in choice of providers. According to a recent national

1

This section draws heavily on West Bengal Human Development Report (2004), published by Development

and Planning Department, Government of West Bengal.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

2

survey, about 79 percent of Indians, who were suffering from minor illnesses, sought treatment from private providers

(NSSO, 2004). It is also important to note that a large number of these providers were unqualified medical

practitioners. Clearly, increasing public finance does not match with growing dominance of these unqualified

providers in the health care market.

1.1.6. The above evidences clearly indicate two fundamental problems of Indian health care system: (1) resources flowing

through the public administrative channels do not necessarily benefit the poor; and (2) even if it does, a common

person in general - and a poor in particular - remains significantly unprotected against the unanticipated burden of

treatment of ailments.

1.1.7. How can we make the health care system work more for the poor? How can the growing vulnerabilities be challenged

with effective policy instruments? How can economic growth be made inclusive of health? These and many other

th

questions need to be addressed to achieve what the Indian Planning Commission stated as their vision for the 11 Five-

year plan It must seek to reduce disparities across regions and communities by ensuring access to basic physical

infrastructure as well as health and education services to all. An important step towards this direction is to bridge in

information gap and to generate relevant evidences that could be used as inputs for informed policy decisions. The

present document attempts to do so and diagnose the challenges on the road towards an equitable future health system.

1.2.1. West Bengal, located in the eastern part of India, ranks fourth among all Indian states in population covering less than

3 percent of the total area of India. It is strategically positioned with 3 international frontiers-Bangladesh, Nepal and

Bhutan. Nationally, it borders the state of Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, Sikkim and Assam. Southern and eastern plains

of the state are better endowed with sufficient water and huge productive land with a sub-humid climate. Extreme

scarcity of water, adverse climatic conditions, poor quality of soil, and low productivity of land are the characteristic

features of north, western and northwestern dry zone. The state is divided into 18 districts which are grouped into

three administrative divisions.

1.2.2. According to 2001 census, the total population of the state is approximately 80.18 million. It covers 2.7 percent of the

India's land area with 7.8 percent of the total population, thus making it the first ranker in terms of population density

of 904 per square kms. The sex ratio in the state was 934 (females per thousand of males) in 2001 as compared to the

national average of 933. The total fertility rate is lower (2.1) in comparison to the national average (2.4). Recent

estimates show that the Crude Birth Rate (CBR) is 18.8 (2005) and Crude Death Rate is 6.4 (2005). The Crude Death

Rate in urban areas (6.8) is less than that of rural areas (7.2).

1.2.3. The state's economy is rapidly progressing although it is still predominantly agrarian and 72 percent of its population

lives in rural areas. However, agriculture contributes only about 27 percent to State Domestic Product (SDP). The

service sector is the largest contributor to SDP which increased from 41 percent in 1991 to 51 percent in 2002.

Between 1994 and 2004, the economy had grown at an average rate of 8 percent per annum and become the third

largest economy in the country with a Net SDP of $ 21.5 billion. Per capita annual income was $395 in 2004, which

1

1.2. A Brief Profile of West Bengal

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

3

Was higher than the national average. The current focus is on rapid industrialization through increasing private

investment.

1.2.4. The state's record in poverty elimination and human development presents a mixed picture. The incidence of poverty

in West Bengal in 1997-2001 was 27 percent of population below the poverty line, marginally higher than the national

average of 26 percent. The performance of West Bengal in terms of household amenities is lower in comparison to

national average. In the late 1990s, only 16 percent of rural households and 68 percent of the urban households had

pucca (concrete) houses compared to 29 percent and 71 percent respectively for all over India. Half the households

have toilet facilities whish is same as of India. In case of access to safe drinking water, 82 percent is getting safe

drinking water vis--vis 62 percent all over India. Electrification has proceeded much slower in the state with only 33

percent having the access, compared to 42 percent all over India. In terms of Human Development Index (HDI), the

th

state ranked 8 among 15 major states indicating an average performance.

1.3.1. The study is largely based on primary data collected from three districts of West Bengal - Malda, Bankura, and North

24 Porgonas (Figure1.1) during November, 2006 through March, 2007. These districts are selected from three

different socio-economic zones of the state. Malda district represents the northern part of the state, which is relatively

backward in term of income, accessibility, literacy status, and other socio-economic indictors. North 24 Porgonas, on

the other hand, is relatively more developed and urbanized and represents the east-central zone of the state which is

also close to the capital city, Kolkata. Bankura district represents the western zone of the state which is historically

backward with more than 10 percent of its populations as tribal.

1.3.2. Primary dataset includes data obtained through following four surveys parallely carried out in the above three

districts:

A households survey covering about 3150 households

An exit interview of 690 out and inpatients in selected government facilities

In-depth interview with 71 Rural Medical Practitioners (RMP) and their associations

In-depth interview with 15 top-level medical officers at selected government hospitals to collect data

on budget, expenditure, collection of user charges, and several other aspects of hospital operations.

Each of the above was executed with a set of structured questionnaire.

1.3. Data and Methods

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

4

Figure 1.1. West Bengal Map and Study Districts

Household survey

1.3.3. For household survey, the households were selected by two-stage stratified sampling: first, from each of the selected

districts, 35 primary sampling units (PSU) covering both rural and urban areas were selected through PPS (Probability

Proportion to Size) method, and second, by selecting 30 households from each PSU through a systematic random

process. In total, 3152 households were selected.

1.3.4. The household survey was conducted using a structured questionnaire which primarily focused on the health seeking

behaviour, utilization of health care facilities, and out of pocket payments of the selected households. More

specifically, the investigation focused on four types of ailing persons:

(1) those who were hospitalized (for inpatient care) in last 365 days;

(2) those who sought outpatient care in last 90 days, but not hospitalized;

(3) those who were suffering from chronic health problems on the day of the survey. Chronic problems were

defined as (i) the person has been suffering from the problem persistently for at least 90 days, and (ii) the

problem has been diagnosed by a qualified health professional

(4) those women who delivered births during last two years.

In addition to collecting quantitative data, several case studies and focused group discussions were conducted in each

district.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

5

Exit interview

1.3.5. For exit interview, 412 outpatients and 278 inpatients (total 690) were interviewed at selected government facilities

including (a) District and sub-divisional hospitals (DH / SDH); and (b) Block Primary Health Centers (BPHCs). For

outpatients, 10 percent of expected inflow of patients was randomly selected. For inpatients, the same percentage of

sample was randomly drawn from the number of patients who were about to be released. Questions were usually

answered by the attendants (relatives) whenever the patients themselves were unable to do so. The interview focused

primarily on three aspects: (1) patients' background, (2) treatment seeking behavior, and (3) various costs of treatment.

Interview with RMPs

1.3.6. RMPs are not officially recognized; hence, there is no official source of information regarding the number of RMPs

and location of their practice. It is, therefore, extremely difficult to apply standard sampling procedures for selecting a

given number of respondents. Keeping this problem in mind, the following two unofficial sources were tapped to

track a number of practitioners on 'as and when found' basis: (1) every district has at least one association of RMPs

which keeps a list of their members. The association was contacted to locate possible respondents, and (2)

information provided by the clients of government health facilities who were contacted through exit interviews. The

focus of the interview was their background, background of their patients, treatment behaviour, earning, referral

behaviour, and so on. In total, 71 RMPs were interviewed through this process. In addition, in-depth discussions with

the RMPs' district associations were carried out in all the three districts.

Interview with government providers

1.3.7. A set of government facilities was visited by the FHS research team to understand the supply side environment

regarding implementation of pro-poor strategies. The visit started from the office of Chief Medical and Health

Officer (CMOH) of the district and also included: (1) District Hospitals, (2) selected Sub-divisional Hospitals, and (3)

selected BPHC / PHC. In all cases, the facility-in-charge (i.e., the chief medical officer) was met and interviewed.

The interview was guided by a checklist about information on collection and exemption of user fee, availability of

drugs, existing mechanisms for targeting poor users, major problems faced by the providers, and so on. In total, 15

facilities of different levels were visited.

Secondary data

1.3.8. The analysis of primary data is supplemented by national level survey data, wherever necessary. Two major datasets

th

were used: (1) National Sample Survey 60 round data on morbidity, health care and the condition of the aged (NSSO,

2004), and (2) RCH district level household survey (RCH-DLHS, 2004). In addition, the preliminary findings from

the recently held National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) were also used. NSSO and NFHS data were weighted

while the other data (including the primary data) were un-weighted.

2. Health Sector in West Bengal

An Overview

2.1. Health Status in West Bengal

2.1.1. As is evident from Table 2.1, the status of health in West Bengal is better than that of the national average by almost all

indicators. It is also to be noted that the state can now be grouped with few relatively better performing states in terms

of its some vital statistics. For example, according to the Sample Registration System (SRS) data, the state has the

fourth lowest birth rate after Kerala, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu; the lowest death rate (same as Kerala), and fourth lowest

IMR after Kerala, Maharashtra, and Tamilnadu among the major Indian states. However, a few indicators also show

less-than average status. Special concern is about prevalence of anemia among adult men and women, which seems to

have higher prevalence in the state in comparison to the national average.

2.1.2. Overall health outcomes are quite impressive in the state, but the gap between rural and urban areas (regarding health

outcomes) is also evident (Table 2.1). The gap may be partially explained by the rural/urban inequalities in health

service utilization. Although health care utilization in West Bengal is better than many other states, Table 2.2 shows

that significant problems exist especially in rural areas. For example, only a half of the diarrhea-affected children

were treated in rural in contrast to two-third of the same in urban areas. A little less than half of the pregnant women in

rural areas received no antenatal care compared to only 13 percent of the urban women.

Table 2.1. Health outcomes: West Bengal and India

Indicator Year West Bengal India

Rural Urban Total Total

Birth rate (per 1000 population)

a

2005 21.2 12.6 18.8 23.8

Death rate (per 1000 population)

a

2005 6.3 6.6 6.4 7.6

Infant Mortality Rate (per 1000 live births)

a

2005 40 31 38 58

Neo-natal mortality rates (per 1000 live births)

a

2003 33 16.0 30 27

% of U-5 deaths to total deaths

a

2003 19.5 8.6 17 23.9

% of children aged 6-35 months with any anemia

b

2005-06 71.9 58.2 69.4 79.2

% of children under age 3 under-weight

b

2005-06 46.7 30.0 43.5 45.9

Total Fertility Rate (per 1000 women)

a

2005-06 2.5 1.6 2.27 2.68

% of ever married men age 15-49 anemic

b

2005-06 35.4 26.9 33.1 24.3

% of ever married women age 15-49 anemic

b

2005-06 65.6 59.0 63.8 56.2

Maternal Mortality Ratio (per 100,000 live births)

a

2001-03 NA NA 194 301

a

Source: Sample Registration System

b

National Family Health Survey (2005-06) (NFHS-3);

Table 2.2. Utilisation of selected health services in West Bengal

Source: National Family Health Survey (2005-06) West Bengal (NFHS-3), provisional data

Health service indicator Rural

(Percent)

Urban

(Percent)

Women who received Antenatal care 55.8 87.3

Deliveries in medical facilities 33.8 79.2

Women who received Postnatal care 29.9 67.4

Children received all vaccinations 62.8 70.3

Women who use any modern contraceptive method 49.9 49.9

Children with diarrhea treated in a health facility 50.0 67.6

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

7

2.2. Health Care System in West Bengal

2.2.1. The state, like any other Indian state, presents an extremely complex landscape of health care service delivery. Public

sector facilities in West Bengal range from 9 teaching (tertiary) hospitals with highly specialized physicians to more

than 10,000 small sub-centers at the village level staffed by Multi-purpose Workers (MPWs). Within this range there

exist various types of public facilities 15 district hospitals, 79 sub-district / state general hospitals (SDH / SGH), 93

Rural Hospitals (RH), 241 Block Primary

Health Centers (BPHC), and 922 Primary

Health Centers (PHC) - arranged in order

of secondary to primary levels of care.

Despite such an arrangement by levels, the

tertiary and secondary hospitals often

unnecessarily serve as first points of

contact for preventive and basic curative

services the product of a weak referral

system. All these facilities are directly

controlled and financed by the Department

of health and family welfare which

accounts for about 56 percent of total

hospital beds, the rest being provided by

other government departments (14%),

2

and the private sector (30%) (Figure 2.1) .

2.2.2. Services in the private sector, similarly, are delivered by a diverse group of service providers. This assortment includes

about 1700 private (for-profit and not-for-profit) hospitals, modern private practitioners, qualified Indian System of

Medicine (ISM) providers, traditional birth attendants, known as dais, and unqualified quacks. The share of this

sector especially in outpatient care market is much higher than that of public sector, both in terms of utilization and

out-of-pocket expenditure.

2.2.3. Adding to the complexity of the service delivery scenario is the dual role of the government health practitioner.

Although there is hardly any documented evidence, it is commonly accepted that many government practitioners

spend a significant portion of their time in private practice, thus blurring the line between public and private. Hence,

an individual who reports that her source of care is the private sector, may in fact be frequenting the after-hours

practice of a government doctor.

Private

30.0%

Government-

health

55.7%

Government-

Others

14.3%

Figure 2.1. Percent distribution of hospital beds

2

Source: Health on the March (2005-06), SBHIDHS, Government of West Bengal, p-83

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

8

2.3. Public Financing of Health Care in West Bengal: An Overview

2.3.1. In 1990, the state spent about Rs. 4600 million on

health which has more than quadrupled over the

next 15 years. Notwithstanding this impressive

hike in investment on health, relative share of

health in total budget, however, declined over the

same period. The decline has its root in growing

fiscal barriers which almost all Indian states have

been subjected to. The increasing fiscal pressure on

the state is quite evident in the fact that the

contribution of Revenue Deficit in Gross Fiscal

Deficit is higher in West Bengal than anywhere else

in the country (RBI, 2006). High and increasing

level of Revenue Deficit indicates a growing

burden of non-plan expenditure in a constrained

revenue-generating environment.

2.3.2. However, despite declining share of public health

expenditure, the government of West Bengal is one

of the top spenders on health on a per capita basis

(Figure 2.3). The per capita expenditure on health

was Rs. 186 (a little less than $5) in 2002-03.

2.3.3. The budget in each department is received and used

3 4

on four major accounts: (1) non-plan , (2) plan , (3)

5

Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) , and (4)

capital account. Among them, non-plan

expenditure remains the major source of public

spending on health in all Indian states. As expected,

the lion's share of this expenditure goes to meet the

salary and wage bill of the staff leaving very

meager resources with the state to spend on

development or non-salary recurrent expenses.

Given the labor-intensity of public health care in

Figure 2.3. Per capita government

expenditure on health, 2003-03 (in Rs.)

86

108

122

147

157

175

176

181

181

186

194

208

210

237

286

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

Bihar

Uttar Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh

Orissa

Assam

Rajasthan

Gujarat

Haryana

Maharastra

West Bengal

Andhra Pradesh

Karnataka

Tamil Nadu

Kerala

Punjab

Per cap exp on health (Rs.)

Figure 2.2. Percentage of government health

spend to total budget (1990-2005)

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

8%

9%

1

9

9

0

-

9

1

1

9

9

1

-

9

2

1

9

9

2

-

9

3

1

9

9

3

-

9

4

1

9

9

4

-

9

5

1

9

9

5

-

9

6

1

9

9

6

-

9

7

1

9

9

7

-

9

8

1

9

9

8

-

9

9

1

9

9

9

-

2

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

-

0

1

2

0

0

1

-

0

2

2

0

0

2

-

0

3

2

0

0

3

-

0

4

2

0

0

4

-

0

5

2

0

0

5

-

0

6

% of health in total budget

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

9

3

Non-plan budget is the part of state budget that is spent for continuation of the programs, which were initiated in the previous plan and considered as

committed liabilities of the state. The recurrent part of the plan budget of an activity is usually transferred to the non-plan budget in the next plan period.

The assistance to fill the non-plan resource gap of the State is determined by the Finance Commission appointed by the Central Government.

4

Plan budget is the part of state budget that covers all expenditures, both capital and recurrent, incurred on programs and schemes that have initiated by the

state during the current five-year plan. The size of the total planned expenditure is determined through a negotiation of the state with the Planning

Commission, a non-statutory permanent body appointed by the Central Government.

5

Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) is the central plan grants that directly finance some selected programs, such as Family Welfare program. Except

Family Welfare program, the central grant under this scheme finances only the plan component of the CSS program.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

10

India, the scenario is unlikely to change unless some strategic initiatives are taken to mobilize additional resources for

development.

2.3.4. The present scenario in West Bengal reflects this strategic move additional resources for planned (or, development)

expenditure as well as for non-salary items (such as, drugs) are pumped into the system to jack up non-salary expenses.

Consequently, the share of non-plan expenditure in total outlay reduced to about 71 percent in the recentbudget (2007-

08) from 77 percent in 2000-01. This has been possible due to two most important steps: (1) mobilizing internal

resources under State Plan; and (2) external supports (such as, budgetary support by DFID and the World Bank).

2.3.5. The districts are the basic implementation units of the state's health care programmes. The district health authority is

the ultimate outlet for using the central and state funds. The funds flow on two routes (1) through the district health

authority directly from the state's health department which primarily covers salary, maintenance and drugs, and

constitutes the major share of total fund flow; and (2) through an autonomous body, called District Health and Family

Welfare Samity (DHFWS) which primarily covers direct expenses of various vertical and centrally sponsored

schemes and constitutes less than 20% of total fund flow (excluding in-kind flows).

2.3.6. DHFWS is an extremely significant intervention to improvise decentralization in financing and decision-making at

the district level. It was formed in 2003 to establish a parallel channel of fund inflow to the districts especially in the

context of centrally sponsored public health programmes. Traditionally, the central funds for each of these

programmes used to flow through individual societies, such as District TB Society, District Leprosy Society, and so on.

These societies were autonomous and funds flowing through them were kept in separate accounts outside the

jurisdiction of public treasury. The individual societies were merged in 2003 to form DHFWS and brought under the

common administration of district health system. The underlying principal of fund flow to the society, however,

remained the same, i.e., the funds are primarily additional to the routine non-plan expenditure of the districts (salary,

drugs, administration cost, etc.) and are to be used exclusively on specific programme activities.

2.3.7 The state has a cost-recovery mechanism in terms of users charges levied on different services at higher-level hospitals

(i.e., tertiary hospitals, district hospitals, and sub-district hospitals). Traditionally, the revenues collected through this

process used to be deposited to state's treasury. However, in most recent times two radical steps have been taken to

ensure autonomy at the service delivery point: (1) formation of an autonomous society (Rogi Kalyan Samiti, or RKS))

at all tiers of facilities (from PHCs to teaching hospitals); and (2) facilities, where user fees are charged (e.g., sub-

divisional, district, and teaching hospitals), would be able to retain a pert of the generated revenue and the remaining

part will go to DHFWS. Impacts of these recent interventions are yet to be assessed, but existing evidences point out

that user fee could hardly recover a significant portion of the cost. For example, a study in 2004-05 [Public

Expenditure Review (2005)] on three sub-divisional hospitals (SDH) and three district hospitals (DH) showed that the

SDHs could recover only 1.56 percent of their total and 8.65 percent of their non-salary expenditure. The

corresponding figures for DH are 2.9 percent and 20.9 percent respectively.

2.4.1. There is now substantial evidence that, despite massive investment by the state governments on health care and heavy

subsidy flowing to primary care, the users of services are still spending a huge amount either directly or indirectly to

2.4. Private Health Care Spending

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

11

avail the services. For example, according to the estimates of a recent national survey (NSSO, 2004), an inpatient

from rural West Bengal spends Rs. 4582 approximately 16 percent of their annual household expenditure - on

hospitalization (corresponding national average is Rs. 6225).

2.4.2. The household survey carried out for FHS research (in three districts of West Bengal) reconfirms the phenomenon of

high out-of-pocket expenses (see Section 1.3 for methodology). Out of pocket expenses (OOPE) include expenses on

all medical expenses (such as, consultation, drugs, IPD charges, diagnostic tests, etc.) and relevant non-medical

expenses (for example, travel, board and lodging, etc.). Table 2.3 presents the mean OOP estimates for each of the

following categories of health care: (1) hospitalization; (2) outpatient; (3) chronic; and (4) birth delivery for all

districts taken together.

2.4.3. The estimated annual per capita (i.e., based on total population) OOPE for overall health care works out to Rs. 657 in

rural, Rs. 867 in urban areas, and Rs. 703 for overall. Based on the estimated per capita public spending on health in

2007-08 (Rs. 210), this accounts for about 77 percent of total government and households taken together expenditure

on health. On average, a rural household spends Rs. 3248 annually on curative health care and birth delivery which

works out to about 11 percent of its annual total consumption expenditure (the corresponding figures for urban areas

are Rs. 3852 and 8%).

In Rs.

Per household Per affected

household

Per user Per capita

Hospitalization 777 4331 3809 157

Outpatient 1092 1170 497 221

Chronic 1280 2633 1895 259

Birth delivery 99 592 392 20

Total 3248 8726 6593 657

Rural

In Rs.

Per household Per affected

household

Per user Per capita

Hospitalization 932 5141 4540 210

Outpatient 1102 1232 569 248

Chronic 1685 3023 2160 379

Birth delivery 133 1117 1117 30

Total 3852 10513 8386 867

Urban

Table 2.3. Estimated annual out of pocket payments for different categories of health care, 3

districts in West Bengal (in Rs.)

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

12

2.4.4. How much does an average household spend on

each of the four categories? Figure 2.4 presents

the distribution of share of each of them in total

medical care expenditure incurred by an average

household (rural and urban taken together).

Hospitalization appears to absorb about a quarter

of a household's medical care expenditure whilst

the expenditure on care for (acute) outpatients

and chronic patients accounts for about 73

percent of the same. The difference between

impacts of inpatient and outpatient care is quite

evident; the financial impact of hospitalization,

which may be disastrous to an affected

household (i.e., the household from where at

least one member was hospitalized) gets

substantially weakened when it is averaged

across all households (since it affects only about

4% of population). In comparison, the impact of

outpatient care is much less on affected

households but more on the whole society since

it affects almost all households.

2.4.5. The results presented in Table 2.3 do not indicate

a significant rural / urban differential with respect to per user OOPE in case of inpatient, outpatient, and chronic care.

For example, an urban resident, when hospitalized, would spend 1.2 times more in comparison to his / her rural

counterpart. The implication is that, on average, rural and urban residents utilize the same level of medical care when

they are hospitalized. The rural-urban differential is more prominent in case of birth deliveries because a large

number of rural women opt for a very cheap option of home delivery.

Figure 2.4. Percentage distribution of

OOPE, by health care categories, 3

districts, West Bengal

Hospitalization

24.0%

OPD

32.3%

Chronic

40.5%

Birth delivery

3.1%

3. Health, Equity and Poverty

Key Issues

3.1. Key issues

I. Health Care utilization

3.2. Good performance in ensuring horizontal equity in inpatient care

The analysis below highlights the following issues that policymakers can address to improve equity in financing, provision,

and use of health care services in West Bengal. These issues are broadly classified into two groups: (1) health care utilization;

and (2) health care financing. The issues are:

I. Health care utilization

Good performance in ensuring horizontal equity in inpatient care

Young and older women have less access to hospitalization

Government hospitals play dominant role, but without much targeting

Outpatient care market is dominated by unqualified providers

Strong barriers against equity in institutional delivery

Inequality in utilization of preventive child health care

II. Health care financing

Equity in public spending is questionable

Poor oversight at the district level

Medicines and test: killing fields

Out of pocket payment is progressive in inpatient care but not so in outpatient care

Growing health poverty in a socially unprotected environment

th

3.2.1. The NSSO 60 round survey in 2004 (NSSO, 2004) estimated total number of hospitalized cases (or, hospital

admissions) in India in a year to be about 2.60 percent of total rural and 3.48 percent of total urban population (Table

3.1). The corresponding estimates for West Bengal (NSSO-2004) are 2.48 percent and 3.94 percent. It is notable that

the estimated rates in 2004 were significantly higher than those in 1995-96 in India as well as in West Bengal (NSSO-

nd

52 round survey).

3.2.2. The last column of Table 3.1 presents the most recent estimates on hospitalization in West Bengal, generated from the

FHS survey in three districts. The estimates are higher than NSSO estimates but closer to the estimates of the

6

Department of Health & FW, Government of West Bengal . It is noteworthy that, overall, the hospitalization rates

have increased in the last 10 years across all socio-economic groups. The rising trend of hospitalization may be

partially explained by the state's persistent efforts to improve the accessibility to hospitals for admissions especially

through State Health System Development Project (SHSDP) implemented in late 1990s through early 2000s.

6

Officially, about 2.6 million cases (i.e., admissions) approximately 3.13% of the state population - were registered in public hospitals (excluding Block

PHCs) in 2005 (estimated from the official website of the Department of Health & FW, Government of West Bengal ). Adding

private hospitals' share and adjusting for average number of admissions per hospitalized person, the most likely estimate would be between 4.0- 4.2%.

- www.wbhealth.gov.in

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

13

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

14

The project focused on strengthening the secondary care hospitals all across the state through a sizeable investment on

infrastructure. It is, however, to be noted that urban hospitalization rate is higher than that of rural rate, possibly due to

easier access to hospitals and more choices an urban resident usually enjoys.

India West Bengal

NSSO

(1995-96)

NSSO

(2004)

NSSO

(1995-96)

NSSO

(2004)

IHMR

(2007)

Poorest 0.5 1.49 0.4 2.03 3.59

Next 20% 0.9 1.99 0.9 2.30 4.80

Next 20% 1.5 2.41 1.4 2.25 3.65

Next 20% 2.1 3.18 1.5 2.81 3.78

Richest 3.7 4.80 2.7 3.22 5.01

All 1.4 2.60 1.2 2.48 4.13

CI 0.37 0.23 0.30 0.08 0.035

Rural

India West Bengal

NSSO

(1995-96)

NSSO

(2004)

NSSO

(1995-96)

NSSO

(2004)

IHMR

(2007)

Poorest

Next 20%

Next 20%

Next 20%

Richest

All

1. 3

1. 7

2.0

2.7

3.8

2. 1

2. 67

3. 49

3. 68

3. 85

4.26

3.48

1.6

1.7

2.2

2.5

3.9

2. 3

3.55

3. 66

4. 32

3. 67

4. 71

3. 94

4.68

4.48

4.04

5.39

4.57

4.62

CI 0.22 0.08 0.18 0.05 0.012

Total

hospitalization

rate (%)

1.7 2.82 1.5 2.83 4.23

Urban

Table 3.1. Rate of hospitalized cases (% of population) in India and West Bengal

3.2.3. How equitable is the hospitalization rate? Does a poor have equal chance to be hospitalized in comparison to a rich

person when they have equal need for hospitalization? The answer is given in terms of concentration index (CI)

presented in the last row of Table 3.1 (see Box 3.1 for a brief note on CI) and representing the degree of inequity in the

rates. It is evident that CI has been sharply progressing towards 0 a state of horizontal equity in West Bengal over the

last ten years (from 0.3 and 0.18 in 1995-96 to 0.035 and 0.01 in 2007, respectively for rural and urban residents)

while the national figure still indicates a significant pro-rich bias especially for rural cases. In other words, a poor and

a rich person have almost equal access to inpatient care in West Bengal it is neither pro-rich nor pro-poor - while,

nationally, the better-offs tend to use more inpatient care.

Box 3.1. Concentration Index (CI)

Concentration index (CI) is a standard tool universally used by the economists to measure the

degree of inequality in various health system indicators, such as health outcome, health care

utilization, and health care financing [Wagstaff, Van Doorslare, and Paci (1989)]. Its value ranges

from -1 to +1. A negative value of CI implies that the relevant health variable is concentrated

among the poor or disadvantaged people while the opposite is true for its positive values. For

example, if the health indicator were Infant Mortality Rate (IMR), a negative CI would imply that

mortality rate is higher among the poorer infants; if it is immunization and CI is positive, richer

children are proportionately more immunized than their poorer counterparts are. When there is no

inequality, CI will be equal to zero. Typically, a zero CI implies a state of horizontal equity which is

defined as equal treatment for equal needs.

In Table 3.1, rate of hospitalization is the relevant health related indicator. A positive CI means that

persons from the richest group get more hospitalized compared to the poorer groups. A pro-poor

strategy for inpatient care should reduce the CI towards a negative value.

The CI values in Table 3.1 were computed by the following three steps (for details, visit

or contact author).

Step 1

First, the population were ranked according to their monthly per capita consumption expenditure

(MPCE); second, the ranked population were grouped in five ascending quintiles (population in

quintile 1 is the poorest and the same in quintile 5 is the richest); and third, number of hospitalized

cases for each quintile was computed by multiplying number of hospitalized persons in each

quintile in a year with how many times they were hospitalized.

Step 2

First, the cumulative percentage of sample population (from quintile 1 through 5) was calculated

this is denoted as p (t=1,,5). Second, the cumulative percentage of estimated cases (from

t

quintile 1 through 5) was calculated this is denoted as L (t = 1,,5).

t

Step 3

Finally, the concentration index is computed by applying the following formula:

CI = (p L - p L ) + (p L - p L ) + ..+ (p L - p L )

1 2 2 1 2 3 3 2 4 5 5 4

The standard errors of the estimated CI were also computed following the methodology given in

the above reference.

www.worldbank.org/poverty/health/wbact/health_eq.htm

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

15

Figure 3.1. Female-male ratio in

hospitalization (3 districts, West Bengal)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

0-14 15-29 30-44 45-59 60 + Total

Age-group

F-M ratio

3.3. Young and older women have less access to hospitalization

3.3.1. Notwithstanding a progress towards more equity in overall hospitalization, one may ask question on gender equity.

For assessing gender perspective in hospitalization, female-male ratio was computed by the following way. First,

female cases per 100 female population and male cases per 100 male population were estimated for each of five broad

age-groups, and second, female rate was divided by male rate and multiplied by 100 to estimate Female-Male (F-M)

ratio. Assuming that need for hospitalization is more or less same between a man and a woman (excluding

hospitalization due to birth deliveries), gender equity is achieved when the ratio is equal or close to 100.

3.3.2. Figure 3.1 presents the F-M ratio for all age groups. It is quite evident that a young girl or an older woman is less likely

to be hospitalized in comparison to their male counterparts. Interestingly and contrarily, the bias against male is quite

prominent in the middle age groups where F-M ratio is significantly greater than 100. Overall, the ratio works out to

be 88 indicating slight bias against females.

3.3.3. Bias against female hospitalization may be explained by the barriers a woman usually faces when she accesses

medical care. These barriers are often prohibitively high especially for inpatient care - treatment is expensive,

inpatient facilities are far away, staying away from home is unaffordable, and so on. Add to this the usually low

perceived severity and high degree of neglect for women's health problem which are not related to childbearing. The

bias against men in their middle age may be partially attributed to their bread-earners' role which often prohibits them

from spending days in hospital.

3.4. Government hospitals play dominant role, but without much targeting

3.4.1 West Bengal is one of the very few states where most people use government hospitals for inpatient care. While

private sector has been expanding its share in the inpatient care market at the national level - from 40 percent of all

hospitalized cases in 1986-87 to about 60 percent in 2004 by NSSO estimates West Bengal remains more like an

exception. According to FHS household survey in three districts, only 18 percent of all hospitalized cases sought

treatment in private hospitals.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

16

Figure 3.2. Share of government and private hospitals in total hospitalized cases, by socio-

economic groups

28

36

43

47

56

72

64

57

53

44

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Richest Poorest

Government Private

64

83

88 87

91

36

18

13 13

9

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Richest Poorest

Government Private

India West Bengal

Source: NSSO (2004) Source: IIHMR (2007)

3.4.2. Absolute dependence of people on government hospitals in the state may be explained by weak presence of private

hospitals in all districts barring a few pockets. A pertinent question is: does this overwhelming presence of

government (in inpatient care) reflect a better pro-poor strategy? The concern for equity forms a key element in

government interventions in health. It is now well accepted that public provision and funding of health care should

primarily target those who, irrespective of their health status, cannot afford to buy health care or pay the insurance

premiums. In other words, in a resource-scarce environment, the public sector should subsidize the neediest segments

of a population. Consumers who are able to pay for services will do so in the private sector where it exists.

3.4.3. The right panel of Figure 3.2 presents the relative share of government hospitals in West Bengal. For comparison, the

relevant NSSO estimates for India are also presented in the left panel. As expected, almost all of the poorest inpatients

(91%) in West Bengal sought admission in government hospitals, but the data also reveals that about two-third of

patients in the richest group had chosen government hospitals for inpatient care implying that public subsidies also

benefit a large section of high-income population who may not need subsidies.

3.4.4. The evidences in Figure 3.2 indicate a near-perfect horizontal equity in utilization of government hospitals (i.e., equal

treatment for equal needs irrespective of socio-economic differential) in West Bengal whilst the Indian scenario

presents a clear and more desirable pro-poor bias. However, one can also argue that it is neither desirable nor feasible

to prohibit richer section from using government hospitals especially when (1) private hospitals are inadequately

available in most of the districts; and (2) apparently the high utilization by the poorest section remains unaffected

implying that poor's interest is still well-protected even if they are not targeted. The argument, which is apparently

sound, may fall flat if there is any crowding out effect in the public facilities especially in the case of hospitalizations

and birth delivery. In other words, a relevant question would be: is there substantial number of poor patients who

could not get admissions in public hospitals because subsidized beds are already occupied by the better-off patients?

Or, alternatively, did some poorest women have to deliver babies at home because those, who were occupying free

beds despite their higher ability to pay, crowded them out? The anecdotal evidences seem to support this hypothesis,

but, no hard evidence has been produced by the studies carried out so far.

Health, Equity and Poverty:Exploring the Links in West Bengal, India

17

3.5. Outpatient care market is dominated by unqualified providers

3.5.1. Despite a strong infrastructural base of the public health care facilities in many Indian states, the majority of outpatient

services, especially in the rural areas, are provided by private health care providers, most of whom practice modern

allopathy without any formal training. This section of medical practitioners is often identified as Rural Medical

Practitioners (RMPs), unqualified, less than fully qualified (LTFQ) providers, or simply quacks. West Bengal

is no exception, where, according to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-II) conducted in 1995-96, about 60

percent of the households visited the private medical sector for outpatient care when they fell sick. Although NFHS-II