Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nodet 2000

Uploaded by

Muammer İreçOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nodet 2000

Uploaded by

Muammer İreçCopyright:

Available Formats

July 2000 tienne NODET

JEWISH FEATURES IN THE SLAVONIC WAR OF JOSEPHUS

There has been in the past much controversy about the attribution to Josephus of

the strange features of the Slavonic, or Old Russian, version of the Jewish War

1

,

made in the 11th century. Leaving aside the so-called Christian interpolations,

this paper aims at renewing the discussion about the Josephan authenticity of the

source (in Greek) of this version, by presenting the reader with two kinds of facts:

first, some peculiar pieces of ancient Jewish exegesis preserved only in this ver-

sion; second, some stylistic features which have an unmistakable Jewish flavor

2

.

I ANCIENT BIBLICAL INTERPRETATIONS

In the Biblical paraphrase of the Jewish Antiquities, Josephus displays idiosyn-

cratic interpretations, as is well known, but sometimes drawn from Jewish lore.

Besides these he witnesses many legal views which are not his own. This is ob-

vious in his summaries of the laws in books 3 and 4, where he brings together

everything he knows and is very careful to stand above any controversy. Some-

times, however, he mentions incidentally some rules that cannot have been ac-

cepted by all. Let us see this from three examples, before moving to peculiar inter-

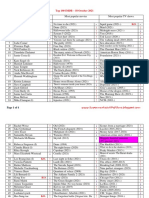

1.The available editions and modern translations are: Alexander BERENDTS & Konrad GRASS,

Flavius Josephus, Vom Jdischen Kriege Buch I-IV, nach der slavischen bersetzung deutsch

herausgegeben und mit dem griechischen Text verglichen, Dorpat, 2 vol., 1924-1927; this

German translation was never completed. Viktor M. ISTRIN, Andr VAILLANT & Pierre PASCAL,

La Prise de Jrusalem de Josphe le Juif, Paris, Institut dtudes slaves, 2 vol., 1934-1938,

with the text and its apparatus, a French translation and a short commentary. A better edition of

the text is given by N. A. METERSKIJ, Istorija iudeskoij vojny Josifa Flavija, Moscow &

Leningrad, 1958, who shows that the translation was made in the 11th century from a Greek

original. A new English translation has been prepared by Bernard ORCHARD (ed.), Josephus

Jewish War and Its Slavonic Version. A Synoptic Comparison (AGAJU), Leiden, Brill, in press.

2.A full-scale discussion of the Josephan authenticity of the Slavonic version of the War is

given as an appendix of Henry St. J. THACKERAY, Josphe, lhomme et lhistorien, adapt de

langlais (Josephus, The Man and Historian, 1929) par tienne NODET, avec un appendice sur la

version slavone de la Guerre, Paris, d. du Cerf, 2000, p. 129-247.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 2

pretations given by the Slavonic War.

1.In Ant. 2:313, after having reported the ten plagues in Egypt, Josephus descri-

bes the sacrifice of the Passover lamb, performed in phratries (small groups of

relatives), and then adds And still now, in accordance with the custom, we sacri-

fice thus, calling the festival Paskha. This statement is really interesting, for

Josephus wrote this some twenty years after the war of 70, while rabbinical tradi-

tion says that this rite cannot be separated from the Temple sacrifices, and thus

must be performed in Jerusalem, when the Temple worship functions. It should be

noted that Philo seems to share Josephus view, for he says that for the Passover

sacrifice the whole people acts as priests, as in Moses time (Spec. leg. 2:146). This

may imply a home rite, unconnected to Jerusalem.

2.On the date of Pentecost, there was a famous controversy. Lev 23:11-15 pres-

cribes a counting of seven full weeks from the day after the Sabbath, which is

also the day of the offering of the first sheaf of the harvest (omer). This Sabbath

is a day of full moon, according to the ancient meaning of the word, and is not ne-

cessarily a Saturday (weekly Sabbath). In fact, it is the very day of Passover (15th

of Nissan, a full moon in the lunar calendar), which may fall anywhere in the week.

Hence a problem for the Pentecost counting: one can take the seven full weeks as

meaning plainly fifty days after Passover; so do the Pharisees, according to m.Me-

nahot 10:4. But the Sadducees and Essenes demand seven true weeks, from Sunday

to Saturday, and Pentecost falls always on a Sunday. Now Josephus, when he ex-

pounds the Law, gives an awkward sentence: When the seventh week after this

sacrifice (i. e. Passover) has passed, these are the forty-nine days of the weeks, on

the fiftieth day, etc. The meaning is purposely ambiguous, so that both schools

can consider that Josephus agrees with them: he wants to stand above any party.

But later on, when he deals with the post-biblical history and does not teach the

laws any more, he says spontaneously that the Pentecost falls on a Sunday (Ant.

13:252), which probably reflects the Temple pilgrimage custom.

3.We may pick up another similar variance about the rules of witnessing. Deut

19:15 states: A single witness shall not prevail against a man for any crime

only on the evidence of two witnesses, or of three witnesses shall a charge be sus-

tained. In Ant. 4:219 Josephus writes, following his source: Let not one witness

be trusted, but let there be three, or at the very least, two, etc. Again, the wording

is awkward, for the mention of three is quite unnecessary: it would suffice to say

let there be at least two, as does Philo, Spec. leg. 4:53. Again, Josephus is build-

ing here a kind of compromise, for we learn later of his own views: in Ant. 8:358,

when Naboth has refused to hand over his vineyard to Ahab, queen Jezebel sends

letters ordering to have three bold men ready to witness that Naboth has

blasphemed God and the king; but 1Kings 21:10 reads two scoundrels. This

indicates that for Josephus a capital conviction requires three witnesses, which is

similar to some Essene rules (CD 9:16-23), but contrary to rabbinical tradition,

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 3

which is content with two witnesses in any case.

This sample shows a consistent pattern: when Josephus follows the wording of

the Bible, he tries to remain faithful to it, but when it is not before his eyes, he may

speak quite otherwise. Another example, taken from Abrahams story, will supply

an interesting connection with the Slavonic.

1. TRADITIONS ABOUT ABRAHAM

Josephus gives two different accounts of Abrahams migration: in Ant. 1:154 he

follows Gen 11-12 and says: At the age of seventy-five (Abraham) left Chaldaea

when God bade him to move to Canaan. Then he adds that Abraham, a phi-

losopher, discovered monotheism, and that for this reason the Chaldeans and other

Mesopotamians fell into discord against him, so that he decided to emigrate in ac-

cordance with the will and assistance of God. This addition is connected with the

ancient view, shared by Josephus, that Abraham is the one who brought wisdom

and pure science to Egypt

3

. But later, as he freely paraphrases another passage, he

gives another interpretation. In Gen 23:13, during Jacobs dream God introduces

himself I, YHWH, am the God of Abraham your father, and the God of Isaac, but

Josephus says (Ant. 1:281) I led Abraham hither from Mesopotamia when he was

being driven out by his kinsmen, and I made your father prosperous. This can be

seen as another story of Abrahams expulsion from Mesopotamia, but remains

difficult to extract from the Bible as it stands.

Now in the Slavonic is given another account of Abrahams expulsion, connec-

ted somewhat loosely with the trial and condemnation of Herods son Antipater

4

(War 1:641):

Therefore it is fitting to marvel at divine Providence, how it requites evil for

evil, but good for good. Ant it is impossible for man to hide before

5

his almighty

right hand, either for the just or for the unjust. But more still does his mighty

eye look upon the just. And indeed Abraham, the forefather of our race, was led

out of his land, because he had offended his brother in the division of their ter-

ritories. And whereby he sinned, even thereby he received also his punishment.

And again for his obedience, (God) gave him the Promised Land.

3.See Steve MASON (ed.) Flavius Josephus. Translation and Commentary, Vol. 3: Judean

Antiquities 1-4, Translation and Commentary by Louis H. FELDMAN, Leiden, Brill, 2000, p. 58.

4.The translations of the Slavonic given here depend on the excerpts prepared by THACKERAY

and printed in the LOEB edition of the War, and on VAILLANTs French translation. We are grate-

ful to K. SARZALA, a student at the cole biblique fluent in Russian, for some spot checks on the

original, for VAILLANT, when the text was corrupted or difficult to render, worked under the as-

sumption that the Slavonic translator was summarizing the Greek War as we know it.

5.I. e. from (semitism).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 4

This legend, otherwise unknown, explains Abrahams migration as a merited

punishment: he wanted to deprive his brother (Haran?) of his share of land, and

eventually lost his own. There is obviously something in common with the

previous expansions, and it may be taken as their core, before any embellishment.

It seems quite foreign to the biblical narrative, but some remote clues can be

detected: first, Gen11:28 says that Haran died in the presence of his father Terah

in their native land, Ur of the Chaldaeans, which may have implied some

inheritance problems, but later on Harans son Lot was with Abraham, and on

returning from Egypt they shared quite fairly the promised land, which may have

been a reverse statement; second, according to v. 31, it was in fact Abrahams

father Terah who left Ur with his whole family to go to the land of Canaan, but he

died in Haran; so in another story he may have been the one who was expelled

from Ur, for he resembles a refugee; third, in Gen 12:5 Abraham looks like a

refugee, who continued his fathers move with all the possessions of the family;

fourth, it seems that the call and blessings of God (v. 1-3) are just the reversal of

the meaning of this painful story. In any case, the narrative of the Slavonic, which

includes some semitisms, cannot be deduced from the canonical Genesis, and it is

hard to hold it as a Christian interpolation.

In another passage, Josephus offers a strange mixture of Biblical fragments.

Commissioned by the Romans to urge the Jews besieged in Jerusalem to surrender,

he gives his own speech, in which he claims that their war is futile, since God is

now on the Roman side. Then he draws some lessons from Biblical history (War

5:380-381; the Slavonic, slightly shorter, has no significant change):

Necho, also called Pharaoh, the reigning king of Egypt, came down with a

prodigious host, and carried off Sarah, a princess and the mother of our race.

What action, then did her husband Abraham, our forefather, take? Did he

avenge himself on the ravisher with the sword? He had, to be sure, three hun-

dred and eighteen officers under him, each in command of a boundless army.

Or did he not rather count these as nothing, if unhelped by God, and uplifting

pure hands towards this spot, which you have now polluted, enlist the invincible

ally on his side? And was not the queen, after one nights absence, sent back

immaculate to her lord, while the Egyptian, in awe of the spot which you have

stained with the blood of your countrymen and trembling at his visions of the

night, fled, bestowing silver and gold upon those Hebrews beloved of God?

Then Josephus proceeds with the exodus from Egypt and other events selected

from the usual Bible. On the contrary, this version of Sarahs kidnapping by Pha-

raoh, if compared with the Biblical version of Gen 12:10-20, looks rather fanciful:

Necho was a king of Egypt, who did invade the country to meet the king of Assyria

at the river Euphrates, but at a much later date (609 BC), by the time of king Josias,

who tried to intercept him and was killed at Megiddo (2Kings 23:29). Now before

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 5

invoking Josephus well known sloppiness to explain away the confusion, we may

observe that again the Biblical narrative itself significantly hints at another story:

first, the very name Chaldaeans given to the inhabitants of Ur, which is really

anachronistic if we follow the Biblical dating of Abraham, fits very well Josias

time (late Israelite monarchy); second, the fact that Sarah was taken into Pharaohs

household by his officials (Gen 12:16) would imply that Abraham was a man

somewhat more established than a starving refugee, unable to settle in Canaan.

To sum up, Josephus witnesses non-biblical traditions about Abraham. Their

origin may be rooted earlier than the final editing of the canonical text, reflecting

some of its raw material. But he does not stand alone in this respect: in 1Macc

12:19-23 the high priest Jonathan quotes an interesting letter sent by Areios, a

former king of the Spartans, to Onias, who was the high priest of Jerusalem for

some time before the Maccabaean crisis (167-164 BC):

It has been discovered in records regarding the Spartans and Jews that they

are brothers, and of the race of Abraham Our own message to you is this:

your flocks and your possessions are ours, and ours are yours, and we are

instructing our envoys to give you a message to this effect.

Besides a chronological problem about king Areios, it is difficult to imagine a

statement by Greeks claiming they are brothers of Barbarians. So this is most

probably a Jewish diplomatic fiction. Its background is twofold: first, the Spartan

connection may refer to Onias origin, as we learn through his brother Jason, who

was compelled to flee and traveled to Sparta, hoping that, for kinships sake, he

might find harbor there (2Macc 5:9). Second, sharing flocks with Spartans from

Greece may look out of place, but it suffices to consider a Spartan colony in Egypt,

from the time of Alexander or later: the very name Onias recalls On, the Egyp-

tian name of the sun (and sun worship, see Exod 1:11 LXX), and it is stated in

1Macc 12:9 that this high priest, appointed in Jerusalem by the Seleucid king, did

not have the sacred books. Now if we focus on Egypt, the problem of the flocks

makes sense for nomads in the desert (Negeb, Sinai). This way we get closer to the

narrative of Gen 13:6-7, when Abraham and Lot, coming back from Egypt, had

too many possessions to live together; dispute broke out between the herdsmen of

Abraham and those of Lot. So there was a real problem of flocks. In any case, the

content of the letter cannot have been extracted from Genesis as it stands, but there

may have been some common origin.

2. CAN HEROD THE GREAT HAVE BEEN THE MESSIAH?

Epiphanius of Salamis

6

declares that Jews have stubbornly persisted in reco-

6.EPIPHANIUS, Panarion, 20.2; see EUSEB, HE 1.6.1. This view is mentioned by later Byzantine

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 6

gnizing Herod the Great instead of Jesus as the Messiah or the king announced

by the prophets. Of course, rabbinical tradition does not allude to this kind of idea,

even remotely. In Matt 2:5, when Herod enquires about the Messiah, the chief

priests and the scribes are far from giving him this title. In Ant. 15:373, Josephus

introduces Menahem, an Essene who once saw Herod when he was a child and

saluted him as the future king of the Jews. Young Herod rebuked him, but Mena-

hem insisted that he would become king, according to Gods will, but later he

would forget piety and eventually be punished for his wrongdoings. Obviously, this

timely recognition by some Essenes, with no hint at fulfilling Scripture, does not

amount to a general acceptance of Herod as the Messiah. Some additions of the

Slavonic, however, provide a clue, in connection with other events.

In War 6:310, Josephus explains that the Jews lost the war, for they did not

understand that God had moved to the Roman side. They had failed to understand

an ambiguous oracle saying that one from their country would become the ruler of

the world: they thought of one from their own race, but in fact the oracle signified

the sovereignty of Vespasian, who was proclaimed Caesar when he was in Judaea.

Tacitus and Suetonius do have sayings to the same effect

7

, and the commentators

have been at a loss, for the source of the prophecy and even its Jewishness are not

obvious.

About this ambiguous oracle, the Slavonic has a useful addition: There are

about it several interpretations. Some understood that this meant Herod, others the

crucified wonderworker

8

, others again Vespasian. According to this, the same

oracle, i. e. the same scriptural prophecy, was deemed to be fulfilled in more than

one occasion.

Now we may come back to Herod, for whom the Slavonic has an important

addition, with discussions involving the Law and the Prophets. After a ferocious

civilian war, Herod has recovered his kingdom (37 BC). But after a short time, he

left Jerusalem for a new war against the Arabs. The addition follows (after War

1:370):

At the time, the priests mourned and grieved to one another in secret, for

writers.

7.TACITUS, Hist. 5.13: pluribus persuasio inerat antiquis sacerdotum litteris contineri, eo ipso

tempore fore ut valesceret Oriens profectique Judaea rerum potirentur; quae ambages Vespa-

sianum ac Titum praedixerat, sed vulgus more humanae cupidinis sibi tantam fatorum magni-

tudinem interpretati ne adversis quidem ad vera mutabantur; SUETONIUS, Vespasian, 4:

percrebruerat Oriente toto vetus et constans opinio, esse in fatis ut eo tempore Judaea profecti

rerum potirentur. Id de imperatore romano, quantum postea eventu paruit, praedictum Judaei ad

se trahentes rebellarunt. Nothing is said of the origin of this opinio, but the statements about the

mistake of the Jews are similar to Josephus, which may point to a common source.

8.I. e. Jesus. The passages mentioning NT characters are not dealt with in this paper, but they

are discussed in my Appendix to THACKERAY (see n. 2).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 7

they did not dare to do so openly, out of fear of Herod and his friends. They

said: Our law bids us to have no foreigner for king (Deut 17:15

9

), and we

wait for an anointed one (Messiah), of Davids line (Amos 9:11

10

), who should

be meek (Zech 9:9

11

). But of Herod we know that he is an Arabian, uncircum-

cised

12

. The Anointed will be called meek, but this is the one who has filled our

whole land with blood. Under the Anointed the lame should walk, the blind see

(Is 35:5), the poor become rich (Is 61:1). But under this man the hale have

become lame, the seeing are blinded, the rich have become beggars. What is

this? Or have the prophets lied? The prophets have written that there shall not

want a ruler from Judah, until the coming of the one to whom the task is given

up; the Gentiles do hope for him (Gen 49:10

13

). But is this man the hope for the

9.Deut 17:15 The king whom you appoint to rule you must be chosen by YHWH your God;

the appointment of a king must be made from your own brothers; on no account must you

appoint as king some foreigner who is not a brother of yours. There were serious discussions

about the Jewishness of Herod: the Galilaean zealots (brigands) never recognized it (Ant.

14:421f.), contrary to the Essenes (or at least Menahem) who did not take into account the

genealogy.

10.Amos 9:11 On that day, I shall rebuild the tottering hut of David, make good the gaps in

it then the rest of humanity (LXX, from ; MT vocalizes Edom) will look for (LXX, from

; MT inherit) YHWH, (quoted in Acts 15:15). This verse, with the reading Edom

may explain, first, some acceptance of Herod, an Idumaean by birth (see n. 12), and second, why

he is called Arabian here, once he is not deemed any more to fulfill Scripture.

11.Zech 9:9-10 Look, your king is approaching, he is just and victorious, humble He will

proclaim peace to the nations, his empire will stretch from sea to sea.

12.I. e. Nabataean. His friend Nicolaus of Damascus claims that Herods father Antipater was a

descendant of the first Jews to return from Babylon (Ant. 14:9), but for Josephus this is plain

flattery, and he says (War 1:123) that Antipater was an Idumaean of noble descent, but this too

may be an embellishment: 1.according to the Slavonic, he was only the first of the Idumaeans

by his wealth and power, without significant descent; 2.EUSEBIUS, HE 1.7.11 quotes sources

indicating that he was carried off as a boy by the Idumaeans in a sack of the Apollo temple in

Ashqelon, and then grew up with them; in other words, his background was rather lowly. So we

may understand Arabian here. On the other hand, the wording Arabian uncircumcised seems

to be an oxymoron, but it is to be taken in a Jewish perspective uncircumcised the eighth day.

Again, this contradicts the facts that the Idumaeans were judaized (circumcised) by John Hyrca-

nus, but here the intended meaning is only non-Jewish descent.

13.In spite of the mention of the prophets, the reference is obviously the blessing of Juda in

Gen 49:10 The scepter shall not pass from Juda, nor the rulers staff from between his feet until

Shiloh comes (so MT; LXX until what is set apart [ ] for him comes, Onqelos

targum until the Messiah comes, to whom is the kingdom) and the nations will render him

obedience. Interestingly, the priests follow the targum rendering, which may have had a Hebrew

background, for the MT ( ) yields no tolerable meaning, and for its part the LXX

refers to something new for Juda (and not to someone). JUSTIN, Dial. 120:3-4 and IRENAEUS,

Haer. 4:10 (as well as some LXX mss) read until comes the one to whom it

(thescepter) is set apart, close to the Targum. These renderings imply a different Hebrew:

or . So the verse becomes clear, but it can be understood in two opposite

ways: the one to whom the scepter of Juda is set apart and who is to be recognized by the nations

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 8

Gentiles? For we hate his misdeeds. Will the Gentile perchance set their hopes

on him? Woe unto us, because God has forsaken us, and we are forgotten of

him (Is 49:14

14

)! And he will give us over to desolation and to destruction, and

not as under Nebuchadnezzar and Antiochus. There were then prophets to teach

the people, and they made promises concerning the captivity and the return

15

.

And now there is neither anybody whom one could ask, nor anybody from whom

one may receive consolation.

Ananus the priest answered and spoke to them: I know all of Scripture

16

.

When Herod fought beneath the city wall

17

, I never had a thought that God

would permit him to rule over us. But now I understand that our desolation is

nigh. Study you the prophecy of Daniel. He writes (Dan 9:24f.) that after the

return (from Babylon) the city of Jerusalem shall stand for seventy weeks of

years, which are 490 years, and after these years it shall be desolate

18

. And

when they (the others) had counted the years, they were 34 years

19

. But Jona-

than answered and spoke: The number of the years are indeed as we have

may be either the last king from Juda or a newcomer after the last Jewish (Judaean) king,

provided that he appears in Juda (Judaea). This way one can understand how Herod (after the

Hasmonaean dynasty) or Vespasian (after the shaky Herodian dynasty) may have been seen as

the one to come.

14.Is 49:14 Zion was saying: YHWH has abandoned me, the Lord has forgotten me. From

this passage it can be seen that the later view that God is on the Roman side does not lack

scriptural background.

15.The reference should be to the written prophecies of Jeremiah and Daniel (see Ananus

reply), but it may imply, and the context suggests, that for them Daniel (or the seer, i. e. one of

the sources of the book) was living by Antiochus IV Epiphanes time, since Jeremiah lived in

Nebuchadnezzars time. We may observe that in his first account of the Maccabaean crisis

Josephus does not follow the books of the Maccabees, but a source connected with Daniel, for he

says that Antiochus plundered the temple and interrupted, for a period of three years and six

months, the regular course of the daily sacrifices (War 1:32), as stated in Dan 9:27 (one half-

week) and 11:21-39 (see below).

16.Or all the books, referring perhaps to more than Scripture. Ananus point here is to stress

that only Scripture matters, and not living prophets (see previous note), and he does move to the

prophecies of Daniel.

17.When he besieged in 37 BC Antigonus, the king of Jerusalem appointed by the Parthians

(War 1:343-353).

18.This statement seems to contradict the prophecy of Daniel, but it is explained below by

Jonathans saying.

19.This seems to mean that there were still another 34 years to run of the 490, and BERENDTS

takes it to mean Herod has 34 years to reign, i. e. from the capture of Jerusalem in 37 to his

death in 4 BC. But this fits poorly the context and would imply that the priests were also pro-

phets. It makes more sense to follow VAILLANT, who understands 434 years, i. e. 7x62 or 62

weeks of years. Indeed, according to Dan 9:26, after the 62 weeks an anointed one (Messiah)

will be put to death, the city and sanctuary ruined, by a prince who is to come. The end of that

prince will be catastrophe, and until the end there will be war and all the devastations decreed.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 9

said. But the Holy of Holies

20

, where is he? For Daniel cannot call the Holy

one this Herod who is bloodthirsty and impure

21

.

But one of them, by name Levi, wishing to outwit them, spoke to them what

he got with his tongue, not out of the books, but in fable. They, however, being

learned in the Scriptures, began to search

22

for the time when the Holy one

would come, and they execrated Levis speeches, saying: Soup is in your

mouth, a bone in your head. They said this because he breakfasted before

dawn and his head was heavy with drink as if it were a bone. But he, overcome

with shame, fled to Herod and informed him of the speeches of the priests,

which they had spoken against him. But Herod sent by night and slew them all,

without the knowledge of the people, lest they should be roused. And he ap-

pointed others.

The context is a series of political events, while this passage focuses on the ful-

fillment of Scripture. Its origin, most probably learned traditions, is different from

diplomatic archives, but its clumsy insertion at the very beginning of Herods reign

makes much sense, as a summary of controversial discussions. The relationships

between Herod and the Jewish religious leaders (priests, scribes, and sanhedrins)

are difficult to assess, for Josephus mentions the topic only incidentally. He says

that when Herod had received the kingdom he slew all the members of the (Jeru-

salem) Sanhedrin (Ant. 14:175), but he was always anxious for recognition as a

legitimate Jewish king, and used to convene several ad hoc sanhedrins for various

purposes.

This passage indicates that for some Herod was deemed to be the Messiah, at

least at the beginning of his reign, the reference verse being Gen 49:10 as under-

20.Dan 9:24 reads Seventy weeks (= 490 years) are decreed for your people and your holy

city for anointing the Holy of Holies. Jonathan confirms Ananus reckoning: the 490 years

correspond to the beginning of Herods reign. This is the span of time allowed to (discover and)

anoint the Holy of Holies; in the case of a failure, desolation is to follow quickly. In other

words, the prophets have not lied, but put a challenge. As for the other priests, they focus on the

62 weeks, and conclude too that a catastrophe is imminent, but it is not clear whether they see

Herod as the Messiah to be put to death, or as the prince who is about to meet his end, but the

discussion itself suggests the former view: some saw Herod as the Messiah, and then led a

discussion about their delusion.

21.We may observe that Daniels prophecy of the weeks is not used in the NT. Mark 24:15

only quotes the end of Dan 9:27 So when you see the appalling abomination, of which the

prophet Daniel spoke, &c. Incidentally, we may note that this prophecy of Daniels obviously

refers to the Maccabaean crisis, but this fact does not prevent its use (i. e. its fulfillment) in other

circumstances (see below).

22.This contradicts the previous discussions, for the search cannot but refer to Daniels pro-

phecies. There may have been two different sources or traditions which grew up from the same

event. The context suggests that for this Levi Herod was actually the Messiah, and that his oppo-

nents are not prepared to accept his arguments from Scripture, probably the same Gen 49,10.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 10

stood by the targum (see footnotes above): the scepter of Juda has been set apart

for the Messiah, which does not imply any Jewish or Judaean descent. This ex-

plains how it could have been attached to such different characters as Herod, the

wonderworker (Jesus) or Vespasian. The move to Daniels prophecies and their

obscure reckoning intends to reject this messianic interpretation. Incidentally, we

may observe that the New Testament does not connect these verses to Jesus.

As for the obvious objection that according to Deut 17:15 the king should be

one of your own brothers, i. e. an Israelite, the answer is that this verse is good

for a normal king, but is outweighed for the Messiah. In other words, if Herod is

not the expected Messiah, he cannot be a legitimate king either, at least for these

priests. In fact, during his reign, he never solved the problem of his own

legitimacy. He was afraid of his opponents, and slew them.

Besides biblical technicalities, one may wonder how some learned Jews may

have conceivably seen Herod as the Messiah. From Ananus words above we may

conclude that he stopped considering him as the Messiah when he saw him leading

a civil war around Jerusalem, but this occurred in 37 BC, three years after he was

appointed by the Senate, in 40. Now, if we move to Rome at that time, we see the

signs of a new era, after a period of civil wars. Octavian gets reconciled with Mark

Antony, who marries his sister and whose expected son will be son of gods. At

the same time Vergil in his fourth Eclogue tells his sponsor Asinius Pollion that

any prosecution, any fear will disappear when the infant lives like a gods son.

Moreover, Josephus stress that Herod was a close friend of the same Asinius Pol-

lion (Ant. 14:388, 15:343). This gives us a clue: Herods appointment can have

been seen by some as a sign of this new hope for the Jews, or even the epiphany of

the true son of god(s), with some relevant biblical background. Roman religious

influence upon the Jews even the Essenes was heavy, but it was always care-

fully judaized

23

. But later on, in Galilee and Judaea, bloodthirsty Herod failed to

meet the expectations attached to such a recognition.

Let us venture a last remark: it seems really difficult to see these very Jewish

Biblical discussions about Herods messianity and fate in Roman time as a

Christian forgery.

3. DID JOSEPHUS WRITE 4MACCABEES?

The so-called Fourth Book of the Maccabees is a discourse to Jews, to show

them that it is not difficult to lead a pious life if they follow the precepts of

religious reason, hence the other ancient title of the book, On the Sovereignty of

Reason. The theme is expounded in a philosophical way, and then illustrated from

23.As shown recently by Israel KNOHL, The Messiah Before Jesus, Tel Aviv, Schocken, 2000

(Hebrew title ; an English translation is forthcoming).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 11

Jewish history, and especially through the martyrdom of old Eleazar and then of

seven brothers and their mother. The main source for this narrative is 2Macc 6:18-

7:41, with minor discrepancies. Its dating is not very clear, but most probably in the

middle of the first century AD

24

, and it may have been written and pronounced

at Antioch.

Eusebius, HE 3.10.6, says that Josephus wrote it and gives both titles On the

Sovereignty of Reason and Book of the Maccabees, the latter being secondary. One

century later, Jerome stated the same authorship in two different places (Vir. illustr.

13 and Contra pelag. 2:6), and then many others followed them

25

, but with no

further evidence. Modern scholars have rejected this attribution, for several good

reasons, chiefly: 1.Josephus does not know 2Macc; 2.the style is different.

But we may ask in the reverse way: On which grounds can it have been as-

signed to Josephus? Some reasons have been adduced: he was the only Jewish

historian of the period, venerated by Christian writers for his impartiality about

Jesus; he was fond of philosophy, especially of common stoicism; he values the

courage and faithfulness of the Essenes, Zealots and others when they face per-

secution, etc.

An addition of the Slavonic provides us with another argument. King Herod had

erected over the great gate of the Temple, in a Greek fashion, a golden eagle, which

was forbidden by Mosaic Laws. At the end of his life, two renowned doctors, ex-

perts in the Law, told their friends and disciples that this was the moment to pull

down these sacrilege structures, even if the action proved hazardous. Then the

Slavonic adds a speech by the two rabbis (summarized in War 1:650):

It is easy to die for the law of our fathers, for immortal glory will follow

those who die thus, while for their souls there awaits eternal joy. But those who

die in unmanliness, loving their body, not desiring a manly death, but finding

their end in sickness, these are inglorious, and will suffer unending torments in

the underworld. Forward, you Jewish men! Now is the time to play the man.

We will show what reverence we have for the Law of Moses, in order that our

people may not be put to shame

26

, in order that we may not offend our lawgiver.

For an example of heroism we have Eleazar first, and the seven brothers, the

Maccabees, and their mother, who acted manfully. For Antiochus, who had

24.Elias BICKERMAN, The Date of Fourth Maccabees, in: Studies in Jewish and Christian

History I, Leiden, Brill, 1976, 276-281, points out that besides stylistic considerations, the title

given to Apollonius, strategos of Syria, Phoenicia and Cilicia (4:9), gives a clue, for these

three regions were put under one governor only for the short period AD 20-54.

25.Andr DUPONT-SOMMER, Le Quatrime livre des Machabes (Bibl. de lcole des Hautes-

tudes, 274), Paris, Libr. H. Champion, 1939, p. XIX, n. 2 gives some references to Church

fathers.

26.In 4Macc 6:29, Eleazar prays God Let my blood purify the people, and accept my soul as

a ransom for theirs; again, this is stressed in the conclusion (17:22).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 12

defeated and captured our country and domineered over us, was defeated

27

by

those seven young men and by their aged teacher, and by the gray-haired wo-

man. We, too, will show ourselves like them, that we may not appear weaker

than the woman. But should we also be tortured for our zeal for God, then our

garland will be better wreathed. But should they even kill us, then will our

souls, after quitting the dark abode, pass over to the forefathers, where Abra-

ham is and those (descended) from him

28

.

This speech has much in common with 4Macc, especially for the philosophical

tenets (see the footnotes), which are viewed as common Judaism, and not specific

to any school or party. As for the narrative details, the two episodes of 2Macc

6:18-31 (Eleazar) and 7:1-12 (the seven brothers) are unconnected, and king

Antiochus is present in the latter only, while in 4Macc he is present to both; the

young men call Eleazar their teacher (9:6). In other words, the speech looks like a

faithful summary, albeit very brief, of 4 Macc.

Many Church fathers used 4Macc for homiletic purposes (among them Gregory

of Nyssa, Chrysostom, Ambrose of Milan), as a model of inalterable faith till

martyrdom. Thus, one could surmise that the present speech is a Christian inter-

polation, artfully worked, stressing the need of resisting any worship of Roman em-

blems. But this would have been a purely literary exercise, somewhat purposeless,

for the passage is devoid of any hint at Christianity, something that never occurs

when ancient Christian writers mention Jewish realities or virtues. The reverse

assumption, that Josephus authored it, is much less unlikely, and offers a very

simple explanation of the attribution to him of 4Macc. The fact that he ignored

2Macc does not imply that he never saw 4Macc, written before the Great War.

Given the style of 4Macc, one may add that it was much easier for him to compose

a shortened speech on a glorious past than to insert the story of the martyrs in the

narrative of the Maccabaean crisis, for his approach to the event is purely political:

in War 1:34-35, he says that the most eminent Jewish defaulters were massacred by

the Greeks until the extravagance of the crimes provoked the victims to venture on

armed reprisals, which began with Mattathias of Modein.

One detail of the Slavonic, however, remains suspicious: the very use of the

term Maccabaean to designate the seven brothers. The word never appears in

4Macc, and the evidence of 1-2 Macc (and even of Josephus himself) shows that

the only true Maccabaean was Judas, who fought against Antiochus Epiphanes

and can hardly be viewed as a martyr. We saw above that according to Eusebius

27.So 4Macc 1:11, 8:15, etc. they defeated his (Antiochus) tyranny.

28.So 4 Macc 18:23 Now the sons of Abraham, as well as their victorious mother, are gather-

ed at the place where the Fathers are, for God has granted them pure and immortal souls. Luke

16:22 says that the righteous are carried away into Abrahams embrace, a frequent metaphor

(see references in STR.-BILLERBECK a. l.)

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 13

the name Maccabees given to the book was secondary. It may have resulted quite

naturally from the insertion of the book into the Greek Bible: two major uncial

manuscripts (Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus) call it , hence the

Christian denomination Maccabaean attached to the martyrs. So we may conject-

ure that here the word Maccabaean is a copyists gloss, or perhaps a comment by

the Slavonic translator: someone noticed the unmistakable relationship between

the speech and the book.

4.MORE ABOUT DANIELS PROPHECIES

After the destruction of Jerusalem, Josephus comments that it was caused by the

misdeeds of the Jews, who were blind and unaware of the plain meaning of some

prophecies (War 6:310): Reflecting on these things one will find that God has a

care for men, and by all kinds of premonitoring signs shows his people the way of

salvation, while they owe their destruction to folly and calamities of their own

choosing. The Slavonic adds:

For God has let appear signs of wrath, so that men may understand the

divine wrath, stop their wrongdoings and thus change Gods mind.

This addition follows the typical pattern of most prophecies, which are above all

warnings: the Prophets call the people to conversion, in order that God cancel his

threats. This reflects the Biblical view, that God lives and changes within history.

This cannot be accepted by Greek philosophy, for which God is necessarily above

time, because time and change mean decay. It rather speaks of fate, and so does

Josephus in many places,

29

but not without inconsistency, for it would remove free

will and moral responsibility.

After this introduction, Josephus proceeds and explains specific prophecies, but

the Slavonic has a different wording.

N. B. The excerpts are disposed in synoptic tables, with the Slavonic on the left, in italics and

the Greek on the right (adapted from the Loeb edition).

(parallel below)

(6:311) Thus the Jews, after the de-

molition of the Antonia (tower), redu-

ced the temple to a quadrangle

30

,

Although there was by the Jews a

prophecy that the city and the temple

would be destroyed by the quadrangle

shape,

although they had it recorded in their

prophecies that the city and the sanc-

tuary would be taken when the temple

would become a quadrangle.

29.See George Foot MOORE, Fate and Free Will in the Jewish Philosophies According to Jose-

phus, HTR 22 (1929), p. 371-389.

30. four-angled. The usual meaning is square, sometimes quadrilateral.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 14

they started making crosses for cruci-

fixion, which includes the quadrangle

shape we said,

(no parallel)

and by the demolition of Antonia they

gave the temple a quadrangle shape.

(parallel above)

In the Greek, the authority behind the prophecy is hard to detect, the more that

quadrangle is generally rendered square, a normal meaning. But the Slavonic,

which parallels the temple shape and a cross, prompts a shift: the common deno-

minator cannot be a square shape, but very literally a four-angled shape.

With this change we are led to a prophecy of Daniel, which was never used

either by the New Testament or by the Church fathers. The angel Gabriel interprets

Daniels vision, where the horns of animals symbolize kings, nations, enemies, etc.

Now Dan 8:22 reads, literally

31

: And the horn which snapped, the four horns

which will sprout in its place, four kingdoms from a nation will rise, and not by its

strength. In the context, the four horns are the four kingdoms that will not have the

strength of the previous one; so run the translations. But the Hebrew word for

horn also means angle and, if we remove the context, we can obtain a very

different meaning: And the broken horn, four angles will sprout in its place, and

four kingdoms (or armies) from one foreign nation will rise, and there is no more

strength.

According to this, Josephus saying becomes clear and rooted: the broken horn

is the Antonia tower, demolished by the Zealots; so the temple court became four-

angled; then a foreign nation came, and the Jews did not have the strength to resist

them; eventually, the war was lost. The same symbolism works with the cross:

one standing man (horn) is replaced by four angles (crucifixion).

Josephus knew Hebrew, and there are very good reasons to think that for his

Biblical paraphrase in the Antiquities he used only a Hebrew Bible

32

. We must

stress that his interpretation of the oracle here, which shows a typically Jewish skill

for dealing with Scripture, cannot be extracted from the ancient Greek versions

(LXX and Theodotion, see the footnote). This may explain why the early Christian

31.Dan 8:22 . The LXX

reads: ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) and the snapped ones, and four horns (are) going up behind him, four kings from his

nation, and not with their strength. Josephus interpretation is not possible with this Greek; one

of the reason is that in Greek horn does not have the same flexibility. Theodotions version is

much closer to the MT, but has like LXX four kings from his nation, i. e. from the nation of

the broken horn, which does not fit Josephus oracle.

32.See tienne NODET, Josephus and the Pentateuch, JSJ 28 (1997), p. 154-194. A sample

ofinstances in the subsequent Biblical books is given in notes 169-178 of my translation of

THACKERAYs Josephus, the Man and Historian (see n. 2).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 15

writers did not use it, though they were anxious to prove that the cause of the

destruction of Jerusalem was Jesus death (they do not specify crucifixion). For

instance, Origen, Contra Celsum, 1:47, looks for the cause of the ruin of Jerusalem

and the destruction of the temple: he claims that Josephus should have said that it

was Jesus death. This statement is instructive: for some reason, he connects the

idea with Josephus, but cannot find any relevant passage in his works as he knows

them. The simplest hypothesis would be that the oracle, in its fuller Slavonic form,

was indeed a Josephan production, which was in public domain for a short time,

and then disappeared for an unknown reason, but which left behind, at least in

some circles of learned scholars, the floating idea that Josephus had much to say

about Jesus.

As for the prophecies of Daniel, Josephus is conversant with them, for they play

an important role in the Antiquities. After his account of the purification of the tem-

ple by Judas Maccabee, three years after its desecration by the Greeks, Josephus

adds that all this occurred according to Daniels prophecy, which was given 408

years before (Ant. 12:322); this refers to Dan 11:21-45, a detailed account of

Antiochus persecutions, where no mention is made of the half-week of years

(9:27, see n. 15). In legends

33

reported in Ant. 11:337, Josephus tells us that king

Alexander came to Jerusalem and worshipped God, in accordance with a previous

vision; then he was showed the book of Daniel and read that one of the Greeks

would destroy the Persians (8:3-8.20-22); eventually he thought he was fulfilling

the prophecy himself. Incidentally, we may observe that this interpretation is closer

to the plain meaning of the prophecy of the horns. But for Josephus, the richer

a prophecy, the more fulfillments it allows.

Much more important is Josephus use of Daniel at the time of the deportation

of the Jews by Nebuchadnezzar (Ant. 10:188-280). He stresses that he has only

undertaken to describe past history, and not to unveil future things, for which he

invites the reader to scrutinize the book itself (210). He lets him understand

that he has done the job but does not want to share his discoveries. More generally,

one cannot help thinking that he views himself as another Daniel, a freed slave in a

foreign, pagan kingdom, who has qualified prophetic skills and strives to save his

nation

34

.

In view of this importance for Josephus of the prophet Daniel, we may ask why

this book, which according to its own dating is more ancient than some of the

minor Prophets (Zechariah, etc.), is not a Prophet in the Massoretic Bible, but only

33.In the same way, Josephus explains (Ant. 11:5) that Cyrus read Isaiahs prophecies con-

cerning him (the release of the Israelites to rebuild the temple), and was anxious to fulfil them.

34.As pointed out by S. MASON in his Introduction to Louis H. FELDMANs Judean Antiquities

(see n. 3), Josephus suggests, too, in the same historical context, that he is another Jeremiah, the

prophet persecuted by his own nation.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 16

a Writing. A Talmudic passage may give a clue. According to b.Megila 3a, Jo-

nathan b. Uzziel made the targum of the Prophets, but at some point there was an

earthquake, and a voice from heaven (bat qol) was heard asking: Who is unco-

vering my (Gods) mysteries? Jonathan stood up and explained that he wanted to

do it to avoid controversies in Israel. This saying is quite instructive, for it seems to

be an exact reply to Josephus prolific exegesis: first, Jonathan was supposed to be

Hillels first disciple (Herods time, or a little later). Second, the translations of all

the Prophets are extant, and attributed to him by rabbinical tradition. Consequently,

the earthquake occurred when he tried to translate a prophetic book that does not

belong any more to the list of the MT Prophets. So it is difficult not to conclude

that the allusion refers to the book of Daniel, which thus was removed from the

Prophets by the Rabbis, in order to reduce its authority. A connected saying indi-

cates that one book contains hidden secrets about the messianic end. This too

surely refers to Daniel.

II JEWISH STYLE

In some instances the Slavonic has another wording than the usual Greek War,

which looks much more Jewish. Broadly speaking it is much shorter, but in these

cases it may have some minor additions.

1.MISCELLANEOUS

We first present three minor examples, which indicate that the Slavonic displays

a more accurate knowledge respectively of Judaism, Hebrew and Aramaic.

1.In 37 BC, three years after his appointment as a king, Herod eventually won

over Antigonus and entered Jerusalem, his capital, with all his allies.

Now Romans and

aliens wanted to get into the temple and

look at the holy places.

(1:354) Now master of his enemies,

Herods next task was to gain mastery

over his foreign allies. For this crowd of

aliens rushed to see the temple and the

holy things of the sanctuary.

The king expostulated, threatened, so-

metimes even had recourse to weapons

to keep them back,

Herod had a hard time,

for he thought to be defeated, should

they have a look into the sanctuary.

deeming victory more grievous than

defeat, if these people should set eyes

on any objects not open to public view.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 17

The Law forbids seeing the Invisible,

even to circumcised servants outside the

priests in function.

So he expostulated, etc

For the Greek version, Herod wants to prevent these aliens from religious

tourism: some beautiful, attractive objects are not open to public view, which is

common cultic custom; no specific authority is given. On the contrary, the Sla-

vonic does not mention the holy things, but focuses on the Biblical prohibition of

seeing God (Exod 19:21-22), i. e. the inner part of the shrine, which is protected by

a curtain.

2.During Antipaters trial in the presence of the Roman legate Varus, his father

Herod charges him. At some point, his emotion prevents him to speak any more

and he signals to his friend Nicolas of Damascus to continue stating the evidence.

But now Antipater, who lay prostrated at his fathers feet, raised his head and cried

out his defense. Here is a part of his speech:

How can you call my piety hypo-

crisy?

How can you call me a serpent, if I do

not know the past and future things?

How could I, cunning in all else, have

been senseless in so serious a matter?

How could I have not perceived, in

concocting so atrocious a crime, that it

would remain concealed from man?

And how to hide it from the judge in

heaven?

(1:630) You call my filial piety

imposture and hypocrisy.

How could I, cunning in all else, have

been so senseless as not to perceive

that, while it was difficult to conceal

from man the concoction of so atrocious

a crime, it was impossible to hide it

from the judge in heaven, who sees all,

who is present everywhere?

In his accusation, Herod calls Antipater a foul monster in the Greek

(324), but the Slavonic puts a serpent. In Antipaters reply, the foul

monster is not mentioned in the Greek any more, but the Slavonic retains the

serpent as an addition, in which Antipaters argument is that he cannot be called

a serpent, for he is not a soothsayer. The reasoning is obvious in Hebrew only, for

the same word ( , with a shift of the stress) has both meanings. But we may

observe that it is not self-evident that this kind of wordplay is a good device in such

a difficult defense before a Roman official. There may have been somewhere a

mistake or a mistranslation. In any case, it is hard to view the addition of the

Slavonic as a Christian interpolation.

AgrippaI decided to build a wall to enclose some later additions to the city,

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 18

especially in the north. Josephus gives a name, and explains it:

Agrippa had added to the fortifica-

tion new walls and called them Bezetha,

or New Town.

(5:151)The recently built quarter

was called in the vernacular Bezetha,

which might be translated into Greek as

New Town.

The Greek has an obvious mistranslation: Bezetha is an Aramaic compound

word which has nothing to do with new town, but means literally house of

olives, i. e. orchard of olive trees. The Slavonic gives simply the two names, but

does not venture to say that the latter is a translation of the former

35

.

In War 2:530 the Greek says more correctly: the district called Bezetha and

also New Town, which is close to the previous Slavonic. Here, the latter has:

Cestius put fire to Bezetha and New Town and the surroundings.

In these three casual details, the Slavonic looks much closer to Jewish culture

than the Greek in secondary issues, with no consequences upon the sense and goal

of the narrative.

2.JOSEPHUS ESSENES AND THE QUMRAN PEOPLE

The Essenes have always been known through the notices of Philo, Josephus

and Pliny the Elder. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) and the excav-

ations of the site of Qumran has given an exciting opportunity to consider them

more closely, because the Rule of the Community (1QS) and other legal documents

displayed many similarity with the tenets of the Essene way of life. But the con-

sensus never remained unchallenged

36

, for there are obvious differences, the first of

which is the plain fact that no Hebrew or Aramaic equivalent of Essene is to be

found in the DSS. Things have got even more complicated, for the most detailed

account on the Essenes, Josephus notice in War 2:119-166, has a close parallel in

Hippolytus Refutation of All Heresies 9:18-29, written in the 3rd cent., but with

discrepancies significant enough for some to have surmised that both depend on a

common source, unknown to us.

The Slavonic has Josephus notice, with some changes, discussed below. They

are interesting, for the general conclusion will be that from a legal point of view

they put the notice much closer to the laws and customs witnessed in the DSS.

35.The parallel in Ant. 19:326 mentions this new town as a noun, but gives no name.

36.A detailed account of the scholarly discussion is given by Steve MASON, What Josephus

says about the Essenes in the Judaean War, in: Stephen G. WILSON and Michel DESJARDINS

(eds.), Text and Artifact in the Religions of Mediterranean Antiquity: Essays in Honour of Peter

Richardson, Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, p. 434-67.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 19

There are by the Jews three religious

orders

37

.

The first is named Pharisees, the

second Sadducees, the third Essenes.

(2:119) Jewish philosophy, in fact,

takes three forms. The followers of the

first are Pharisees, of the second Saddu-

cees; the third, which is reputed to, and

certainly does, behave with dignity, is

called Essenes.

They are Jewish by nation, and show

a greater attachment to each other than

do the other sects.

The Greek has two peculiarities, which do not appear in the Slavonic. First,

Josephus stresses the pious reputation of the Essene and their philanthropy, which

is a major line of his apologetics (Apion 2:146). Second, the mention Jewish by

nation seems to be a pleonasm, since Josephus just said it. Many hypotheses have

been ventured to explain Josephus insistence

38

. The simplest is to consider that

this is a kind of wishful thinking, for it is not obvious that the Essenes are necessa-

rily Jewish by birth: in 120 Josephus says that they disdain marriage, but

they adopt other mens children and mould them in accordance with their own

principles (the Slavonic adds: They teach them Scripture). This indicates that

for them only education matters, not genealogy. Later on he says, about the four

classes of Essenes (150): So far are the junior members inferior to the

seniors, that a senior if but touched by a junior must take a bath, as after contact

with an alien ( ). In other words, non-Jews and junior members

(neophytes) convey the same legal impurity, which indicates that circumcision is

unimportant. Of course, Josephus cannot accept this, for in his paraphrase of Gen

17:8 he says (Ant. 192): Because God wished his (Abrahams) posterity to remain

unmixed with others, he ordered that the genitals be circumcised on the eighth

day after birth.

The same features can be seen in the DSS: some Samaritan traces have been

found. Genealogy is unimportant, at least from a priestly point of view

39

. Above

all, the Covenant is not attached to circumcision, but to the success of the purific-

ation pedagogy, marked by baptisms, and concluded by the full admission into the

37.The underlying Greek had probably , which occurs in the Greek version about the

schools, and specifically five times for the Essenes.

38.See the review of Shaye J. D. COHEN, Y and Related Expressions in

Josephus, dans: Fausto PARENTE & Joseph SIEVERS (Eds.), Josephus and the History of the

Greco-Roman Period. Essays in Memory of Morton Smith (Studia Post-Biblica, 41), Leiden,

Brill, 1994, p. 23-38.

39.Daniel R. SCHWARTZ, On Two Aspects of a Priestly View of Descent at Qumran, in: Lau-

rence H. SCHIFFMAN, Archaeology and History in the Dead Sea Scroll, Sheffield Academic Press,

1990, p. 157-180.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 20

community.

Oil they consider defiling. (123) Oil they consider defiling,

and anyone who accidentally comes in

contact with it scours his person; for

they make a point of keeping a dry

skin

40

.

A defilement cannot be removed only by a bath (see above). Wiping off a stain

is by no means a purification; the explanation of the Greek, which involves the

hygienic properties of oil (in Greek culture) is out of place, from a Jewish point of

view, and is inconsistent with the numerous purification baths mentioned in the

sequel.

They occupy no one city, but

settle in every town.

Everyone, where he wants, enrolls some

companions and builds a house and

dwells there.

(124) They occupy no one city, but

settle in large numbers in every town.

On the arrival from other cities of un-

known people from other communities,

but of the same observance,

they go to them as to their community,

and they are not refused food and drink.

On the arrival of any of the sect from

elsewhere, all the resources of the

community are put at their disposal, just

as if they were their own;

and they enter the houses of men whom

they have never seen before as though

they were their most intimate friends.

For the Greek, the whole Essene reality is one united, large, network, with over-

all spontaneous fraternity and sharing. But the Slavonic has both additions and

omissions that definitely alter the picture, which becomes much less idealized:

there is not one Essene community, but many, with clear-cut borders. Incidentally,

this suggests a really simple explanation of the very word Essene. Scholars agree

that its two Greek forms (essaios, essenos) are transcriptions of the two Aramaic

plural forms ashaya/ashain. The Hebrew equivalent is assidim, which does not

mean pious, saint, righteous but faithful to, i. e. disciples of. Thus each

community has its own founder (master) and his faithful or disciples. Of course,

all the communities have the same general pattern, but they certainly have minor

differences in their customs.

All this may throw some light upon another small difference between the two

40.Or to remain unwashed ( ).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 21

versions. In 152, the Greek says that the Romans had tortured the Essenes in

order to induce them to blaspheme the lawgiver or to eat some forbidden things,

while the Slavonic reads to blaspheme their lawgiver, &c. Some have thought

that their in the Slavonic refers to the founder of the whole movement, i. e. the

Teacher of Righteousness of 1QpHab. But in view of the different pictures

given by the two version, we may suggest that their refers to the individual leader

or founder of each group. In the Greek, the can hardly refer to Moses, for he is

not named; more probably the founder of the united movement is meant, perhaps

the so-called Teacher of Righteousness of the DSS.

The diversity of the Essene groups and networks suggested by the Slavonic fits

more closely the variety of Essene individuals we meet in Josephus history (seers,

hailers, one general). Moreover, it makes the comparison with the DSS much

easier, for they reflect many trends within a common culture

41

.

The description of the Greek has a touch of perfect Judaism, or even perfect

society. It adds that in every city there is one of the order expressly appointed to

attend the strangers, who provides them with raiment and other necessaries. This

develops an important rule of the Essenes in the two versions, that that they do not

have personal use of money, nor private property either. For Josephus, this is the

salvation of the city, which has been intrinsically cursed since the vicious deeds of

greedy Cain, who became a teacher of vicious activities; and by the invention of

measures and weights he transformed the simple life he was the first to set

boundaries of land and built a city and fortified it with walls, necessitating his

kinsmen to congregate in the same place (Ant. 1:61-2).

Towards the Deity they are pious

above all.

They do not rest much. They get up

every night to sing Gods praises and

pray.

Before the sun is up they utter no word

but offer to the sun certain

ancestral prayers, as though entreating

it to give its light.

(128) Their piety towards the Deity

takes a peculiar form.

Before the sun is up they utter no word

on human matters, but offer to it certain

ancestral prayers, as though entreating

it to rise.

41.It also helps explaining the origins of rabbinical Judaism. Saul LIEBERMAN, The Discipline

in the So-Called Dead Sea Manual of Discipline, JBL 71 (1952), p. 199-206, has shown that the

differences between 1QS and early rabbinical halakha is no greater than the internal rabbinical

controversies. In tienne NODET & Justin TAYLOR, The Origins of Christianity: An Exploration,

Liturgical Press, Collegeville (Min.), p. 205-218, we show that GamalielII, the actual founder of

the Yabneh Academy on a large scale (with the goal of reorganizing Judaism in Judaea after the

war), strove to federate various groups, many of them being Essene-like, hence many contro-

versies, for each one had its own traditions.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 22

The Greek version seems to imply some worship of the sun, which has intrigued

the commentators, for this seems to be the idolatry scorned in Ezek 8:16: They (i.

e. the sinners) had their backs to YHWHs sanctuary and their faces towards the

east; they were prostrating themselves to the east, before the rising sun. Further-

more, in 148 the sun is identified with God: (for going to stool) they dig a

trench and wrapping their mantle about them, that they may not defile the rays of

the Deity, they sit above it. But all this may be attributed to Josephus own views

or at least to his spontaneous phraseology, for a little later he claims that the Zeal-

ots polluted the Deity when they left corpses unburied beneath the sun

42

(War

4:382-383).

The Slavonic says only that these Zealots transgressed both divine and natural

laws when they laughed at the sight of stinking corpses under the sun. In that

version the passage about digging a trench reads that they may defile neither the

sun nor the divine rays. Now from the Slavonic addition above it is clear that for

the Essenes the rising sun is important, but it is not God, whom they have wor-

shipped by night. So the rising sun is just a sign that God has agreed the prayer

and gives a new day. The same feature can be seen in Zechariahs blessing (Luke

1:78), which mentions Gods love in which the rising sun has come from on high

to visit us, a strange metaphor indeed. We may add that the Jerusalem Temple,

too, is open towards the east (Ant. 4:305), and that Josephus explains that Moses in

the desert positioned the Tabernacle so as to catch the suns first rays (3:115). But

the Essenes reject the Temple, and consider the congregation as the shrine itself, so

it makes sense that they embody some of its features.

The addition of the Slavonic about the night prayer has been viewed as a typical

interpolation made by Christians, maybe by the monks who translated the text, but

again there is a parallel custom in the DSS. The Rule of the Community says (1QS

6:7-8): And the many shall be on watch together for a third of each night of the

year in order to read the book, explain the regulation and bless together. The

similarity is obvious

43

.

The one anxious to join their life

is not immediately admitted

but they let him live in premises in front

of the door.

(137) The ones anxious to join

their sect are not immediately admit-

ted. For one year,

during which he remains outside.

42.As noted by S. MASON, art. cit. (n. 36), who observes also that in Ant 1:282-283 God

parallels his watching over the earth with the suns.

43.As remarked by Marc PHILONENKO, La notice du Josphe slave sur les essniens, Semitica

6 (1956), p. 69-73.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 23

If (the candidate) appears worthy,

they enroll him in their community.

(138) If he is found worthy,

he is enrolled in the society.

But before they enroll him,

they bind him by

tremendous oaths,

and he standing before the door

44

pled-

ges himself with tremendous oaths, invo-

king the living God and calling to witness

his almighty right hand and the Spirit of

(139) But before he may touch the

common food, he is made to swear

tremendous oaths:

God, the incomprehensible, and the Se-

raphim and Cherubim, who have insights

into all, and the whole heavenly host,

that he will be pious, etc. first that he will practice piety, etc.

The addition of the Slavonic has a flavor of ritual Hebrew formulae, to be

uttered by the neophyte: living God, almighty right hand, etc. The whole

heavenly court is called to witness, but the angels remain unnamed, as stipulated

later (146). The Rule of the Community (1QS1-2) has too an admission

ritual, with lengthy formulae. The general outline is different: first, the neophytes

confess their sins (as well as their forefathers

45

) and praise Gods grace; so they

cut away family ties. Then the priests pronounce a blessing and the levites curse

the sinners and threaten the neophytes if they go astray: May he (God) hand you

over to dread into the hands of all those carrying out acts of vengeance. Accursed,

without mercy, for the darkness of your deeds and sentenced to the gloom of

everlasting fire, etc. And the neophytes reply after them Amen, amen. The ones

entitled to punish in the name of God are angels, but here too their names are

veiled, at least in writing.

Here Hippolytus has a good contact with the Slavonic, for he says that the

candidates eat their meals in another house. In other places he has some minor

pluses and minuses in common with the Slavonic, but he does not know its major

additions and features, and conversely the Slavonic ignores his peculiarities (on the

women, the love of enemy, the division into classes, endurance and resurrection).

44.The idea and rite of admission by entering, dimmed in the Greek, is very clear too in 1QS

1:16 And all those who enter in the Rule of the Community shall establish a covenant before

God in order to carry out all that he commands, and in order not to stray from following him for

any fear, dread or grief. Here the covenant is concluded personally by the neophyte; it is

deemed to be stronger than any fear, which amounts to the terrible oaths of Josephus.

45.In the ritual of the feast of the Booths (m.Sukkot 5:4) there is too a confession of the sins of

the fathers, who turned their backs to the Temple and worshipped the rising sun (after Ezek 8:16

quoted above), but now the people turn towards the Temple. The reference is not to the remote

sinners of Ezekiels time, but to some Essene-like recent ancestors (see above note 41, about the

origins of the Rabbinical traditions).

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 24

So no useful conclusion can be drawn from his account.

They are very strict in the observance

of the seventh

day,

the seventh week, the seventh month

and the seventh year.

On Saturday they do not prepare their

food,

they do not kindle any fire,

they do not remove any vessel,

they do not go to stool.

(147) They are stricter than all Jews

in abstaining from work on the seventh

day

46

,

for not only do they prepare their food

on the day before,

to avoid kindling a fire on that one, but

they do not venture to remove any vessel

or even to go to stool.

The Greek has two peculiarities: first, what is called here seventh day is

actually sevens, which conveys a strange, unjustified ambiguity (see the note);

second, the expression do not venture to remove implies some fear of a kind of

magical punishment, but this is no more than one of the many rules of the Essenes.

The Slavonic removes both stylistic flaws, and adds interesting details, espe-

cially the seventh week, i. e. the Pentecost, which is really important in the DSS.

First, it is the main festival

47

: the feast of the Covenant (represented by the com-

munity itself), the day of receiving new members, the feast of the first fruits (of

theHoly Land). Moreover, the seventh day (Sabbath) and the seventh year

(sabbatical year) are perpetual cycles which rest upon Biblical authority. This

suggests the same for weeks and months. Some DSS (4QMMT, 11QT) show

that the solar calendar includes at least for the relevant communities a cycle of

Pentecosts or pentacontads, which always fall on Sunday. Each one celebrates the

first fruits of the main crop of the time, but prepared for human consumption:

bread (in May-June), new wine (July-August), olive oil (September-October), and

perhaps other ones later. The Therapeuts described by Philo have too a cycle of

pentacontads, but no other details are given

48

.

As for the seventh month, nothing significant emerges. One may observe,

somewhat artificially, that starting from Nisan, the first month of the festival year,

which contains Passover, the seventh month is Tishri, with the Day of Atonement

46. every seven; the word means a number of seven, which is here

ambiguous, for it may refer to days, weeks, months or years. The context does not even suggest

specifically the seventh day, for the very word Sabbath occurs elsewhere (War 1:147, 2:365,

450, 518). Anyway, the translation has to restore it, because of the well-known Jewish custom

(Biblical law).

47.A fuller statement is given in NODET-TAYLOR, The Origins (see note 41), p. 392-399.

48.PHILO, De vita contemplativa 65. They have a special gathering every seven weeks,

and stress the meaning of the square of the week (7x7), but no mention is made of first fruits.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 25

(the utmost Sabbath) and the Feast of the Booths; and starting from Tishri, the

first month of the Creation (ordinary) year, the seventh month is Nisan

49

. But this

comment is no more than a lame play on the numbers, with does not add to the

Bible any specific Essene or DSS reworking.

To sum up, it is clear that for Josephus the Essenes are a model of Jewish life.

This is more obvious in the usual Greek version, where their main qualities are

stressed: piety, philanthropy and unity. In Apion Josephus insists on theses

qualities as typical of Judaism, and it has been pointed out that some of the laws

and penalties have much in common with Essene tenets. In other words, he has an

apologetic bias.

The Slavonic version is less embellished (no unity!) and does have more ritual

and legal contacts with the DSS. But even so Josephus Essene can by no means be

equated with the Qumran community, far away from any city and unable to extract

any first fruit from the soil of the Promised Land. But some remarks should be

made to qualify this community: 1.the DSS have been written by hundreds of

copyists, which suggest they came from a much larger area; 2.at Qumran, the

excavations have unearthed some unbroken bones of sheep and goats, properly

buried in clay pots, which indicates that some holiness was attached to them; the

simplest explanation proposed so far is that these are the remains of Passover

lambs

50

; 3.the Biblical idea of a new foundation of the Covenant in the desert is

emphasized by the DSS, but it does not entail permanent life in the desert; a com-

memoration may suffice. The model is Joshua: from the desert he brought the Is-

raelites across the Jordan river into the Promised Land, then renewed the Covenant,

celebrated Passover and let the people eat some first fruits. Now Qumran is quite

close to the Jordan river, and it would make much sense to have there some facil-

ities for a kind of Passover pilgrimage, on the spot or in the vicinity

51

.

III A TENTATIVE EXPLANATION

The material of the Slavonic version of the War presented in this paper has been

49.These two beginnings of the year, which are Biblical, are explained by Josephus, AJ 1:81

and 3:239-248, and by m.Rosh haShana 1:1.

50.Jean-B. HUMBERT, Espaces sacrs Qumrn, RB 101 (1994), p. 161-214.

51.Dominique BARTHLEMY, Notes en marge de publications rcentes sur les manuscrits de

Qumrn, RB 59 (1952), p. 199-203, cites Al-Biruni, an Arab historian of the 11th cent., who

quotes DSS discovered around AD 800; one of them states that Passover must be celebrated

within the Land of Israel, but does not mention any specific holy place.

BIBLICAL EXEGESIS BY JOSEPHUS 26

preserved only in this marginal tradition. But it can hardly be considered as inter-

polations made by learned Christian copyists. This Slavonic is much shorter than