Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Referensi Jurnal

Uploaded by

Ferry Ghifari0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views7 pagesreferensi

Original Title

referensi jurnal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentreferensi

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views7 pagesReferensi Jurnal

Uploaded by

Ferry Ghifarireferensi

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics 2009; 51: 527-533 Original

Protective effect of breastfeeding on diarrhea among children

in a rapidly growing newly developed society

Mohammad S. Ehlayel

1

, Abdulbari Bener

2,3

,

Hatim M. Abdulrahman

4

Units of

1

Allergy and Immunology, and

4

Gastroenterology, Department of Pediatrics, and

2

Department of Medical

Statistics and Epidemiology, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar, and

3

Population Health Unit, Department of Evidence,

University of Manchester, School of Epidemiology and Health Sciences, Manchester, United Kingdom

SUMMARY: Ehlayel MS, Bener A,

Abdulrahman HM. Protective effect of

breastfeeding on diarrhea among children in a rapidly growing newly developed

society. Turk J Pediatr 2009; 51: 527-533.

In developed communities, the effect of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is

encouraged since it has been found to be protective against infantile diarrhea.

In a newly developing Qatar, modern water supply and sanitation facilities

have become available to everyone during the last two decades. The objectives

of the current study were to explore the relationships between

breastfeeding

and diarrhea and to assess the effect of EBF on the risk reduction of diarrhea

in children aged 1-5 years. This is a cross-sectional survey conducted in the

Well-Baby clinics and pediatric clinics in the 11 Primary Health Care (PHC)

Centers and Hamad General Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar. A

multistage sampling design was used, and a representative sample of 1500

Qatari infants and pre-school children in the age group of 1-5 years and

mothers aged between 18 to 47 years were surveyed during the period from

October 2006 to September 2007; 1,278 mothers agreed to participate in this

study, with a response rate of 85.2%. The sociodemographic characteristics,

feeding modes and diarrhea morbidity were collected from the parents of the

children during the interview. Of the 1,278 infants studied, more than half

(59.3%) were EBF, followed by those partially breastfed (28.3%), and finally the

formula fed (12.4%). The duration of EBF was 11.46.7 months (meanSD)

and the duration of partial breastfeeding with bottled milk was 9.24.1 months

(meanSD), and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.0010). When

compared to the EBF infants, the risk of diarrhea was higher and statistically

significant in both the partially breastfed (48.7% vs 32.5%) and in the non-

EBF (37.3% vs 32.5%, p<0.001). Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI),

short duration of breastfeeding, level of maternal education, and sterilization

of bottles were considered as predictors. These results indicate that in Qatar,

breastfeeding plays an important role in reducing the incidence and severity of

infantile diarrhea. This observation is particularly important given the growing

concern that, as an unwanted effect of modernization, breastfeeding is on

the decline in Qatar and comparable populations elsewhere.

Key words: infant feeding, breastfeeding, diarrheal diseases, upper respiratory tract

infection, risk factors, Qatar.

Human milk is considered an ideal nutrition

and provides advantages regarding general

heal th, growth and devel opment, and

psychological and social benefits

1

. Being readily

available and economic, breast-milk makes

breastfeeding an effective preventive measure

against allergic diseases

2

. In 2003, the World

Health Organization (WHO) issued a revised

global recommendation that mothers should

breastfeed exclusively for six months. This

recommendation is likely to influence national

policies on the recommended age for the first

introduction of solids, so it is important that

pediatricians are aware of the issues and the

evidence (or lack thereof) on which the WHO

recommendation is based

1

. In developing

countries, breastfeeding reduces the incidence

and severity of diarrhea in infants

1-9

, although

528 Ehlayel MS, et al The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics November - December 2009

this effect may be less pronounced in areas with

better water supply and sanitation facilities

3-

5

. An important

limitation of many of these

studies is that they did not use the

currently

recommended classification of breastfeeding,

i.e., exclusive,

predominant (almost exclusive),

and partial, thus not

permitting the protection

afforded by each to be assessed.

Modem

water supply and sanitation facilities are also

thought to at least partly explain the absence

of protection by exclusive breastfeeding (EBF)

against infantile diarrhea, as seen in some

studies in developing countries

1-18

.

There is ample evidence of a positive influence

of breastfeeding, especially of EBF, on diarrhea.

Yoon et al.

6

reported a higher risk of mortality

due to diarrhea associated with no

breastfeeding.

A similar

pattern has also been reported

from other studies

3-10

.

In a recent meta-

analysis of data from six developing countries,

breastfeeding provided a greater degree of

protection against

diarrhea attributable to acute

respiratory infection in the

first six months of

life, whereas the level of protection was similar

for infants who were 6 to 11 months of age

(WHO 2000)

1,4,10

.

The WHO recommends

1-18

that all infants

be exclusively breastfed for six months

1

. In

developing countries, EBF has a large protective

effect on infant mortality and severe morbidity.

However, the public health importance of

breastfeeding in healthy, term infants in

developed countries has rarely been quan-

tified

4-17

. Few studies have assessed the effect

of breastfeeding on hospitalization rates in such

settings. These observations raise the question

of whether protection by breastfeeding against

infantile diarrhea in developing countries will

decline with improvements in water supply and

sanitation. We considered Qatar an ideal site

for this study because in this rapidly growing

and newly developed traditional society, modem

water supply and sanitation facilities have become

available to everyone during the last two decades.

The objectives

of the current study were to

explore the relationships between

breastfeeding

and diarrhea and to assess the effect of EBF on

the risk reduction of diarrhea.

Material and Methods

The infant and pre-school children studied were

the subjects of this cross-sectional population

study conducted in both urban and semi-

urban areas of Qatar. Approval for the study

was obtained from the Medical Research

Committee of Hamad General Hospital, Hamad

Medical Corporation. Mother-child pairs were

enrolled only after informed verbal consent

was obtained from the mother and other adult

family members who were present.

Study Design and Population

The potential subjects of this study were all

children aged 1-5 years and their mothers

visiting the childrens immunization centers at

the Primary Health Care (PHC) Centers. These

children are considered as a representative

sample of all Qatari children in our target age

group because: (a) children in the State of

Qatar visit immunization facilities according to

a standard schedule; (b) in Qatar, the National

Health Authority provides all childrens vaccines

free of charge; and (c) current coverage rates

for individual vaccines in Qatar children aged

<4 months range from 90-99%

7

. Of the many

immunization centers for children in Qatar,

we chose these hospital-based centers because

they serve large numbers of children daily. Our

choice of PHC Centers as the study setting is

unlikely to introduce selection bias because

in Qatar, parents can take their children for

immunization to any of the government centers

as convenient.

The sample was comprised of Qatari male and

female children in the age group of 1-5 years.

The study was performed at the Well-Baby

Clinics in the 11 PHC Centers (PHCC) of the

Hamad Medical Corporation, State of Qatar.

The PHCC sample was adjusted proportional

to subjects from each clinic obtained from the

daily visits for immunization and Well-Baby

clinics by systematic sampling technique. The

sampling plan controlled the factors underlying

heterogeneity among PHCC visits such as age,

sex and socioeconomic level. Accordingly, the

sampling plan included stratification based

on these variables, together with multistage

sampling. The infants and children who were

sampled from each PHCC were chosen with

probability proportional to the substrata sizes

by a simple random sample. A multistage

sampling design was used and a representative

sample of 1500 infants and pre-school children

with an age range of 1-5 years and mothers

aged between 18 to 47 years were surveyed

during the period from October 2006 to

Volume 51 Number 6 Does Breastfeeding Prevent Diarrheal and Respiratory Diseases? 529

September 2007 in Qatar. A total of 1,278

mothers (85.2%) consented to participate in

this study.

Data Collection

A pre-tested structured questionnaire was used

by one of the authors (AB) to obtain data

from each enrolled mother during a personal

interview. During the interview, collected

data about the child included date of birth,

gender, birth order, parental consanguinity,

socioeconomic status, mothers age, mothers

educational level, mothers occupation,

breastfeeding mode, technique for sterilization

of bottles, and incident diarrhea. Data related to

diarrhea included the total number of episodes

and the place of treatment for each episode.

Definition of Variables

Diarrhea was defined as the presence of three

or more liquid or semi-liquid stools per day

accompanied with or without mucus

or fever.

The total number had to exceed the usual

number of daily

bowel movements. Incident

diarrhea in the child was defined by the mother

as the onset of stools that were more frequent

and/or fluid than normal. The end of a diarrheal

episode in the child was defined by the mother

as the point when both the frequency and

fluidity of stools became normal.

Acute upper respiratory tract infection (URTI)

was defined as the presence of runny nose or

cough for at least two consecutive days plus

one

or more of the following signs independent

of duration: erythematous

mucosa, hoarse cry,

respiratory distress, or fever. Erythematous

mucosa was considered to be positive only

when written in medical

records.

Based on each mothers report as to the usual

dietary intake of her child three months prior

to the interview, we grouped the children as

fully breastfed (intake of breast milk without

regular supplements), partly breastfed (regular

intake of both breast milk and supplements),

and non-breastfed (no intake of breast milk

at all) at baseline.

In the current survey, breastfeeding was defined

by the question, How was he/she fed in the

first three months of life?. The parent could

answer (1) breastfed only, (2) bottle-fed only or

(3) breastfed and bottle-fed. Exclusively breastfed

(EBF) was defined as the breastfed only group.

Data Analysis

Chi-square test was performed to test for

differences in proportions of categorical

variables between two or more groups. In 2x2

tables, the Fisher exact test (two-tailed) was

used instead of chi-square, in particular, when

the sample size was small. Multiple logistic

regression analysis using the forward inclusion

and backward deletion method was used to

assess the relationship between dependent and

independent variables and to adjust for potential

confounders, and orders the importance of risk

factors (determinant) for diarrhea in children.

A level of p<0.05 was considered as the cut-

off value for significance.

Results

Table I shows the sociodemographic charac-

teristics of diarrhea morbidity in the children

studied. Out of 1,278 infants, 458 (35.8%) had

diarrhea episodes. The risk for presenting diarrhea

were higher and statistically significant in male

children (55.5%, p=0.002) and in infants of

mothers with low educational level (p<0.05).

Table II describes characteristics of the surveyed

children by mode of feeding. Of the studied

1,278 infants, more than half (59.3%) were EBF,

followed by those partially breastfed (28.3%),

and finally the formula-fed (12.4%). The duration

of EBF was 11.46.7 months (meanSD) and

the duration of partial breastfeeding with bottled

milk was 9.24.1 months (meanSD), and the

difference was statistically significant (p<0.0010).

As can be seen from this Table, when compared

to the EBF infants, the risk for diarrhea was

higher and statistically significant in both the

partially breastfed (48.7% vs 32.5%) and in the

non-EBF (37.3% vs 32.5%, p<0.001).

Table III presents multivariate stepwise logistic

regression analysis for possible risk factors

associated with the incidence of diarrhea

episodes. The result revealed that acute URTI,

duration of breastfeeding, formula-feeding,

partial breastfeeding, maternal educational

level, and technique for sterilization of bottles

were considered as diarrhea predictors after

adjusting for the childs age, gender and other

independent variables.

Discussion

Despite the universal access to modem water

supply and sanitation facilities in Qatar, we

have detected a substantial positive association

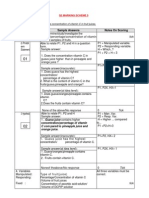

Table I. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Prevalence of Diarrheal Episodes in the

Children Surveyed (N = 1278)

Characteristics

Diarrheal Episodes

p-value

Yes

n (%)

No

n (%)

Number 458 (35.8) 820 (64.2)

Childs age

0.024

1-2 years 137 (16.8) 100 (21.6)

3-4 years 500 (61.47) 286 (61.8)

Above 5 years 177 (21.7) 77 (16.6)

Childs gender

0.002

Male 254 (55.5) 378 (46.1)

Female 204 (44.5) 442 (53.9)

Childs birth order

NS

1-2 215 (46.9) 393 (47.9)

3-4 168 (36.7) 311 (37.9)

5-8 75 (16.4) 116 (14.1)

Parental consanguinity

NS

Yes 171 (37.3) 278 (33.9)

No 287 (62.7) 541 (66.1)

Maternal age group (Years)

NS

<25 104 (22.7) 225 (27.4)

25-34 282 (61.6) 469 (57.2)

35 72 (15.7) 126 (15.4)

Maternal educational level

0.05

University 91 (19.9) 150 (18.3)

High School 204 (44.5) 313 (38.2)

Secondary School 55 (12.0) 140 (17.1)

Primary School 45 (9.8) 94 (11.5)

Illiterate 63 (13.8) 123 (15.0)

Maternal occupation

NS

Housewife 324 (70.7) 600 (73.2)

Professional 96 (21.0) 151 (18.4)

School teacher 32 (7.0) 57 (7.0)

Police / Security officer 6 (1.3) 12 (1.4)

Family income

NS

Low (<US$2,750 /month) 103 (22.5) 198 (24.1)

Medium (2,750-4,130 US$/month) 221 (48.3) 422 (51.5)

High (>US$4,130/month) 134 (29.3) 200 (24.4)

Accommodation type

NS

Villa-semi villa 213 (46.5) 399 (48.7)

Traditional house 77 (16.8) 123 (15.0)

Apartment flat 168 (36.7) 298 (36.3)

NS = Not significant.

530 Ehlayel MS, et al The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics November - December 2009

Table II. Associations Between Feeding Modes and Diarrhea Morbidity in the

Children Surveyed (N = 1278)

Variables

Baseline feeding modes

p-value EBF PBF NEBF-Formula

Number of subjects n=758 n=362 n=158

Mean duration of breastfeeding (MeanSD) 11.46.7 9.24.1 <0.001

Diarrhea

<0.008

Yes 246 (32.5) 135 (37.3) 77 (48.7)

No 512 (67.5) 227 (62.7) 81 (51.3)

Childs age

NS

1-2 years 205 (27.0) 91 (25.1) 34 (21.5)

3-4 years 292 (38.5) 135 (37.3) 58 (36.7)

Above 5 years 261 (34.4) 136 (37.6) 66 (41.8)

Diarrheal episode

<0.001

Never 512 (67.5) 227 (62.7) 81 (51.3)

Once per week 34 (4.5) 22 (6.1) 11 (7.0)

Once per month 42 (5.5) 27 (7.5) 24 (15.2)

Every 3 months 67 (8.8) 32 (8.8) 24 (15.2)

Every 6 months 76 (10.0) 36 (9.9) 12 (7.6)

Once in >6 months 27 (3.6) 18 (5.0) 6 (3.8)

Treatment of diarrhea

<0.01

None 512 (67.5) 227 (62.7) 81 (51.3)

At home 87 (11.5) 47 (13.0) 21 (13.3)

PHCC visit 122 (16.1) 66 (18.2) 42 (26.6)

Hospital visit 37 (4.9) 22 (6.1) 14 (8.9)

NS

Sterilization of bottles

Chemical 60 (7.9) 33 (9.1) 16 (10.1)

Boiling water 96 (12.7) 48 (13.3) 14 (8.9)

Steam 82 (10.8) 52 (14.4) 27 (17.1)

Washing with plain water 249 (32.8) 102 (28.2) 56 (35.4)

Combination 271 (35.8) 127 (35.1) 45 (28.5)

URTI

NS

Yes 256 (33.8) 115 (31.8) 52 (32.9)

No 502 (66.2) 247 (68.2) 106 (67.1)

EBF: Exclusive breastfeeding. PBF: Partially breastfed. NEBF: Non-EBF. NS: Not significant. PHCC: Primary health care

center. URTI: Upper respiratory tract infection.

Table III. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Possible Predictors and

Risk Factors Associated with Incidence of Diarrhea

Independent variables Relative risk 95% confidence interval P value significance

URTI 4.31 3.38-5.50 0.001

Formula-fed 2.68 1.52-4.38 0.001

Short duration of breastfeeding 2.18 1.51-3.08 0.001

Maternal educational level 1.93 1.19-3.15 <0.008

Partially breastfed 1.60 1.09-2.34 0.015

Sterilization of bottles 1.52 1.06-2.18 0.024

URTI: Upper respiratory tract infection.

Volume 51 Number 6 Does Breastfeeding Prevent Diarrheal and Respiratory Diseases? 531

between breastfeeding and diarrhea in the

study children aged 0-5 years. During the three

months of follow-up of the study children,

episodes of diarrhea were commonest among

the non-breastfed infants followed by the

partially breastfed infants, and least in the

EBF infants. These results confirm a protective

effect of EBF against infectious diseases-related

morbidity in infancy. The observed protection

remained even after adjustment for a number

of confounders, including demographic (age and

gender of child) and socioeconomic variables.

The results showed that children aged 0-3

month(s) who are exclusively breastfed were

less likely to have suffered from diarrhea or

an acute respiratory infection than non-EBF

infants. The results are consistent with those

of other studies on the association between

mode of feeding and diarrhea morbidity in

children

3-9

.

The effect of potentially confounding variables

is a major concern in studies of the association

between feeding modes and diarrhea in

children.

1,1l

To address this issue, we adjusted for

several potentially confounding variables during

analyses by using bivariate and multivariate

methods. Demographic, health and social factors

can affect the prevalence of EBF. In our study,

mothers who were less educated were less likely

to breastfeed their children exclusively for the

six months. The authors suggest that education

is a proxy for socioeconomic status, which could

be related to exposure to advertisements and

the capability of buying infant formula.

Studies in developing countries have found

variability in the effect of breastfeeding on

the development of diarrhea. In diarrheal

disease studies reported in Nigeria

5

, the

Philippines

6

, Peru

8

,

Sri Lanka

10

, Malaysia

18

,

and India

19

, there was a stronger protective

effect of breastfeeding on diarrheal diseases.

Similarly, in Bangladesh, it was shown that

breastfeeding practices against diarrhea

can

be achieved through community-based and

health education campaigns

3,9,12

. A study in

Malaysia

18

found that formula feeding had a

much stronger effect on mortality in infants

living in households without piped water or a

toilet than in households with toilets.

In a more recent study by Quigley et al.

17

, it

was reported that breastfeeding, particularly

when exclusive and prolonged, protects against

severe morbidity in the contemporary United

Kingdom. A population-level increase in

exclusive, prolonged breastfeeding would be

of considerable potential benefit for public

health. Our findings are consistent with

previous observations of a negative relation

between breastfeeding and diarrheal morbidity

in children in areas with modem water

supply and sanitation facilities

12-14

. Finally,

the mechanisms through which breastfeeding

may protect children against diarrhea are well

recognized

4

.

There is a large body of data describing how

the immunologic properties of breast milk

are likely to protect against infection in the

infant

17,20,21

. In addition, infection may be

attributable to contamination of bottles, teats,

milk, and food in non-EBF infants. In our

developed country setting, where rates of

infection and poor hygiene are relatively low,

the immune properties of current breast

milk do not seem to persist after breastfeeding

cessation. Alternatively, the immune properties

may not persist at sufficient levels to protect

against contamination.

Promotion of EBF in the first four to six

months of life and reduction in the current

practices of giving potentially

contaminated

drinks or foods are likely to be beneficial

for infant

survival in this population, with

reductions expected in both

diarrhea and

URTI deaths, as well as in all deaths. This is

consistent with

earlier estimates of potential

reductions in diarrhea mortality

after increased

breastfeeding

15-19

. Thus, estimates indicate

that

infant mortality could be reduced by almost

one-third if

the prevalence of EBF in the first

four months

of life could be raised to nearly

80%, with smaller gains with

intermediate

improvements in breastfeeding practices. In

Egypt, early initiation of breastfeeding was

associated with a marked reduction in the rate

of diarrhea throughout the first six months of

life

22

. Recent studies

in Bangladesh showed

that such improvements in breastfeeding

practices

can be achieved through community-

based interventions

9,12,15

. Furthermore, a study

conducted in Brazil

23

showed that the chance

for presenting diarrhea was 64% higher in

children younger than six months who were

not breastfed compared to breastfed children,

and when compared to the EBF children,

the chance for presenting diarrhea increased

532 Ehlayel MS, et al The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics November - December 2009

to 82% in children who were not breastfed.

Breastfeeding and EBF were protective factors

against diarrhea in the first six months of life.

This latter study confirms our index survey in

the State of Qatar.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded, in part, by a research

grant from MSD, Merck Research Laboratories,

Rahway, NJ, and supported by the Research

Committee of Hamad Medical Corporation,

Doha, State of Qatar.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding.

Policy Statement. Breastfeeding and the use of human

milk. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 496-506.

2. WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of

Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality.

Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality

due to infectious diseases in less developed countries:

a pooled analysis. Lancet 2000; 355: 451-455.

3. Haider R, Islam A, Hamadani J, et al. Breast-feeding

counselling in a diarrheal disease hospital. Bull WHO

1996; 74: 173-179.

4. Quigley MA, Cumberland P, Cowden JM, Rodrigues

LC. How protective is breast feeding against diarrheal

disease in infants in 1990s England? A case-control

study. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91: 245-250.

5. Oni GA. Infant feeding practices, socio-economic

conditions and diarrheal disease in a traditional

area of urban Ilorin, Nigeria. East Afr Med J 1996;

73: 281-282.

6. Yoon PW, Black RE, Moulton LM, Becker S. Effect

of not breastfeeding on the risk of diarrheal and

respiratory mortality in children under 2 years of age

in Metro Cebu, the Philippines. Am J Epidemiol 1997;

143: 1142-1148.

7. Annual Heal th Report 2007. Hamad Medi cal

Corporation, Doha, State of Qatar.

8. Brown KH, Black RE, Lopez de Romana G, Creed

de Kanashiro H. Infant-feeding practices and their

relationship with diarrheal and other diseases in

Huascar (Lima), Peru. Pediatrics 1989; 83: 31-40.

9. Arifeen SE, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui AH, Caulfield

L, Becker S. Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute

respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants

in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics 2001; 108: 67-74.

10. Lauer JA, Betran AP, Victora CG, de Onis M, Barros

AJ. Breastfeeding patterns and exposure to suboptimal

breastfeeding among children in developing countries:

review and analysis of nationally representative surveys.

BMC Med 2004; 2: 26.

11. Bahl R, Frost C, Kirkwood BR, et al. Infant feeding

patterns and risks of death and hospitalization in the

first half of infancy: multicentre cohort study. Bull

WHO 2005; 83: 418-426.

12. Mihrshahi S, Ichikawa N, Shuaib M, et al. Prevalence of

exclusive breastfeeding in Bangladesh and its association

with diarrhea and acute respiratory infection: results

of the multiple indicator cluster survey 2003. J Health

Popul Nutr 2007; 25: 195-204.

13. Perera BJ, Ganesan S, Jayarasa J, Ranaweera S. The

impact of breastfeeding practices on respiratory and

diarrheal disease in infancy: a study from Sri Lanka.

J Trop Pediatr 1999; 45: 115-118.

14. Al-Ali FM, Hossain MM, Pugh RN. The associations

between feeding modes and diarrhea among urban

children in a newly developed country. Public Health

1997; 111: 239-243.

15. Mitra AK, Rabbani F. The importance of breastfeeding

in minimizing mortality and morbidity from diarrheal

diseases: the Bangladesh perspective. J Diarrheal Dis

Res 1995; 13: 1-7.

16. VanDerslice J, Popkin B, Briscoe J. Drinking-water quality,

sanitation, and breast-feeding: their interactive effects

on infant health. Bull WHO 1994; 72: 589-601.

17. Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Breastfeeding and

hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection

in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study.

Pediatrics 2007; 119: e837-842.

18. Knight SM, Toodayan W, Caique WC, Kyi W, Barnes

A, Desmarchelier P. Risk factors for the transmission

of diarrhea in children: a case-control study in rural

Malaysia. Int J Epidemiol 1992; 21: 812-818.

19. Bhandari N, Bahl R, Mazumdar S, Martines J, Black

RE, Bhan MK (Infant Feeding Study Group). Effect of

community-based promotion of exclusive breastfeeding

on diarrheal illness and growth: a cluster randomised

controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 361: 1418-1423.

20. Morrow AL, Rangel JM. Human milk protection against

infectious diarrhea: implications for prevention and clinical

care. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2004; 15: 221-228.

21. Abdulla EM, Zaidi FE, Zaidi A. Immune factors in

breast milk: a study and review. Pak J Med Sci 2005;

21:178-186.

22. Clemens J, Abu Elyazeed R, Rao M, et al. Early

initiation of breastfeeding was associated with a marked

reduction of rate of diarrhea throughout the first 6

months of life. Pediatrics 1999; 104: e3.

23. Vieira GO, Silva LR, de O Vieira T. Child feeding

and diarrhea morbidity. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2003;

79: 449-454.

Volume 51 Number 6 Does Breastfeeding Prevent Diarrheal and Respiratory Diseases? 533

You might also like

- SUMMARY Pediatric Reference Ranges For Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers FixDocument2 pagesSUMMARY Pediatric Reference Ranges For Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers FixFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal FerryDocument21 pagesJurnal FerryFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument43 pagesJurnalFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading Risk Factors For Death in Children During Inpatient Treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition A Prospective Cohort Study (Summary)Document2 pagesJournal Reading Risk Factors For Death in Children During Inpatient Treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition A Prospective Cohort Study (Summary)Ferry GhifariNo ratings yet

- PneumoniaDocument5 pagesPneumoniaFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading Word 2 FixDocument2 pagesJurnal Reading Word 2 FixFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Pnemonia PDF 438.fullDocument21 pagesPnemonia PDF 438.fullYidnekachew Girma AssefaNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2007 Quigley E837 42Document8 pagesPediatrics 2007 Quigley E837 42Ferry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Minor Thesis Guidelines Rev 2012Document27 pagesMinor Thesis Guidelines Rev 2012Dini PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal FerryDocument21 pagesJurnal FerryFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Pembahasan Lichenoid TranslateDocument1 pagePembahasan Lichenoid TranslateFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Pendekatan Diagnosis AnemiaDocument7 pagesPendekatan Diagnosis AnemiaFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading (13) -β-D-Glucan in Cerebrospinal Fluid as a Biomarker for Candida and Aspergillus Infections of the Central Nervous System in Pediatric Patients (summary)Document2 pagesJournal Reading (13) -β-D-Glucan in Cerebrospinal Fluid as a Biomarker for Candida and Aspergillus Infections of the Central Nervous System in Pediatric Patients (summary)Ferry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Session 14 - Transboundary & Global Health ConcernsDocument20 pagesSession 14 - Transboundary & Global Health ConcernsFerry Ghifari67% (3)

- WHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Document160 pagesWHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Jason MirasolNo ratings yet

- Taking The National Gaps e Methods PaperDocument15 pagesTaking The National Gaps e Methods PaperFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Rating ScalesDocument4 pagesPsychiatry Rating ScalesFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Taking The National Gaps e Methods PaperDocument15 pagesTaking The National Gaps e Methods PaperFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors CadDocument2 pagesRisk Factors CadFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Referensi Jurnal Rotavirus BMCDocument7 pagesReferensi Jurnal Rotavirus BMCFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- GoutDocument3 pagesGoutFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument9 pagesJurnalFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2007 Quigley E837 42Document8 pagesPediatrics 2007 Quigley E837 42Ferry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Referensi Jurnal Rotavirus BMCDocument7 pagesReferensi Jurnal Rotavirus BMCFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- Referensi Diare Rota Virotrus NCBLDocument6 pagesReferensi Diare Rota Virotrus NCBLFerry GhifariNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Investec FMCG Research - Jyothy Labs Limited - Septermber 2019 PDFDocument151 pagesInvestec FMCG Research - Jyothy Labs Limited - Septermber 2019 PDFvishal shindeNo ratings yet

- Free Wheelers - 1-Test Pack-Students PDFDocument39 pagesFree Wheelers - 1-Test Pack-Students PDFHeshamNo ratings yet

- Complex Prepositions British English TeacherDocument7 pagesComplex Prepositions British English TeacherBianca BilckNo ratings yet

- All in One Cappuccino Espresso and Coffee Maker COM53X Manual v2 EN FR ESDocument35 pagesAll in One Cappuccino Espresso and Coffee Maker COM53X Manual v2 EN FR ESBilly WNo ratings yet

- Claim - Sienna SnowDocument237 pagesClaim - Sienna SnowNUEVO SUSANNA N.No ratings yet

- CH13. Fire Safety Requirement For Multi-Tenant (Terrace TypDocument10 pagesCH13. Fire Safety Requirement For Multi-Tenant (Terrace TypArun UdayabhanuNo ratings yet

- Basic French Conversation GuideDocument37 pagesBasic French Conversation Guidemrmi09100% (2)

- Le Noir Online MenuDocument5 pagesLe Noir Online MenuJerry TomNo ratings yet

- Adam Magazine v03 n11 1959 11Document67 pagesAdam Magazine v03 n11 1959 11falokel169No ratings yet

- Paul Full MenuDocument6 pagesPaul Full MenuChris HughesNo ratings yet

- Bret King #1 The Mystery of Ghost CanyonDocument178 pagesBret King #1 The Mystery of Ghost CanyonPastPresentFuture100% (3)

- Organic Derivatives of WaterDocument9 pagesOrganic Derivatives of Waterpagaduanjoshuaj8227100% (2)

- Homemade Mosquito TrapDocument4 pagesHomemade Mosquito TrapAnonymous qBh9dBOW60% (1)

- Ans Q2 6.1 Vit CDocument3 pagesAns Q2 6.1 Vit Cnikkishya28No ratings yet

- (1886) Catalogue of The Relics and Curiosities in Memorial Hall, Deerfield MassachusettsDocument116 pages(1886) Catalogue of The Relics and Curiosities in Memorial Hall, Deerfield MassachusettsHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Meat CanningDocument8 pagesMeat Canningdemo1967No ratings yet

- Pre-Test - English 3Document2 pagesPre-Test - English 3Maranela G. AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Preform Design For PET BottlesDocument4 pagesPreform Design For PET BottlesWerner Schrammel100% (1)

- Unit 3 SkimmingDocument12 pagesUnit 3 SkimmingdiditNo ratings yet

- Exercise 3 MS WORD EXERCISESDocument3 pagesExercise 3 MS WORD EXERCISESTivar Victor100% (1)

- The Translation of ModalsDocument6 pagesThe Translation of ModalsRed RoseNo ratings yet

- China Top Beverage PDFDocument8 pagesChina Top Beverage PDFEveline PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Tong ChampagneDocument50 pagesTong ChampagneSajjadNo ratings yet

- 21 Day Express Workout ProgramDocument18 pages21 Day Express Workout ProgramZam Bisu100% (1)

- Kameleon 2010Document32 pagesKameleon 2010Loren RaadNo ratings yet

- Count and NonCount NounsDocument19 pagesCount and NonCount NounsBerna GüzelderenNo ratings yet

- UrcDocument2 pagesUrcjustine aguilon100% (1)

- Ica FestividadesDocument4 pagesIca Festividadesjavier valdiviaNo ratings yet

- DACs GROUPDANIEL ALFANTE CAGUICLA With AbstractDocument8 pagesDACs GROUPDANIEL ALFANTE CAGUICLA With AbstractJacob LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Food ChallengeDocument3 pagesFood ChallengeDaniela Ioná BrianeziNo ratings yet