Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bk767Supp Hampton

Uploaded by

Shinzholic Mertty0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views8 pagesWriting structures, coherence, and cohesion are essential to writing and reading. Writing reveals what we know; more than anything else it is the measure of our learning. When a writer works intensively with language--at the whole text level, the paragraph level, the sentence level.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWriting structures, coherence, and cohesion are essential to writing and reading. Writing reveals what we know; more than anything else it is the measure of our learning. When a writer works intensively with language--at the whole text level, the paragraph level, the sentence level.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views8 pagesBk767Supp Hampton

Uploaded by

Shinzholic MerttyWriting structures, coherence, and cohesion are essential to writing and reading. Writing reveals what we know; more than anything else it is the measure of our learning. When a writer works intensively with language--at the whole text level, the paragraph level, the sentence level.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 1

The Importance of Writing Structures, Coherence, and Cohesion to

Writing and Reading

Sally Hampton

For a text to be recognized as a text rather than a haphazard collection of sentences, it must

have an orderly and cohesive construction.

John Chapman

Think of cohesion as the experience of seeing pairs of sentences fit neatly together, the way

Lego pieces do. Think of coherence as the experience of recognizing what all the sentences in a

piece of writing add up to, the way lots of Lego pieces add up to a building, bridge, or boat.

Joseph Williams

Writing

The ultimate goal of in-school writing is the expression of ideas and knowledge. Writing well,

more often than not, is essential to academic survival. Essay tests, research papers, college

application letters, Advanced Placement examinations, the ACT, and the SAT all require student

writing proficiency. This primacy of writing proficiency is not misplaced: Writing reveals what

we know; more than anything else it is the measure of our learning. It unlocks the mind and

forces the writer to organize and synthesize thinking.

When Ernest Boyer, then president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of

Teaching, was asked how to know if a given high school was doing a good job, he answered that

simply having all the seniors write an essay on a subject of their choice and then reading those

essays would reveal more about the quality of the school than would any other measure (Tagg,

1986). What would be learned from this exercise would, of course, go far beyond the declarative

knowledge students could display in that essay.

You would see simply by topic choice what the student thought significant and what

was best ignored.

You would see how the student made sense of the informationhow particular chunks

were woven into clusters and what the overarching ideas were.

You would see the degree to which the student could demonstrate actual understanding

of the content and the amount of depth present in that understanding.

You would see the students facility with languageor not.

You would see the writers thinking.

Think about what a writer has to be able to do. When she writes, she works intensively

with languageat the whole text level, the paragraph level, the sentence level, and the word

level. And at each level she needs tools. She needs genre knowledge to help organize and present

her thinking to structure whole text. She needs facility with paragraphing and syntax to help

layer meaning and create linkages between the ideas she works to express. She needs a good

vocabulary for precise word choice, which is critical to making writing explicit. Additionally,

she needs knowledge of grammatical structures and punctuation to make the writing intelligible

to readers. And finally, she needs to be able to bring everything together and make her whole

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 2

message coherent. Three of these toolsgenre knowledge, cohesion, and coherenceare the

structural underpinnings of text. They guide both readers and writers and should, therefore, be

essential in any ELA curriculum.

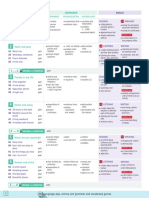

Genres and Mid-Level StructuresThe Macrostructure

A writer will organize her thinking in a particular wayamong other options, choose a particular

genreto convey her message in a form that a reader will find intelligible/effective. Genres are

recognizable text types. They are rough templates that writers use to order their thinking.

Moreover, genres are, according to Charles Cooper, types of writing produced everyday in our

culture, types of writing that make possible certain kinds of learning and social interaction . . .

essential to thinking, learning, communication, and social cohesion. The most common school

genres include narrative and some of its subgenres, such as the memoir, the autobiographical

incident essay; the informational genre (exposition) including subgenres of problem/solution,

reports of information and explanations, and argument, including such subgenres as response to

literature, the position paper and the evaluation (Dornan, Rosen, & Wilson, 2003). Genre

knowledge on the part of the writer opens up an array of options that aid in the organization and

generation of text (Graham & Harris, 1993). Genre knowledge on the part of a reader allows that

reader to anticipate where the writer is headed next with her thinking; it allows for anticipation

and ease of understanding.

Understanding of mid-level structures offers similar benefits. Working within the

structure of comparison/contrast or cause and effect, of problem and solution, or

definition/example, gives the writerand the readera predictable template to follow.

While the genre and mid-level structures (macrostructure) of text are the global means of

both organizing and following the writers message, at the sentence and paragraph levels of text

(microstructure) are the propositions (idea units) that link together to make up the web of

meaning intended by the writer (van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983).

Paragraphs and SentencesThe Microstructure

A paragraph is a single sentence or a group of sentences set off as a unit. Paragraphs are

characterized by unitya focus on one main ideaby coherenceall thoughts clearly related to

each otherand by developmentadequate and specific details to elaborate the main idea

(Connors & Lunsford, 1993). Paragraphs are arranged within a text so that their topics cohere.

They are linked by some reference to the preceding paragraph. (The reference itself can be either

explicit or implied). Like the linkages used to join sentences, paragraph linkages are most

typically, repetitions of a key word or term, parallel structures, pronouns, or transitional

expressions.

The sentence brings fragments of information together to become complete ideas. It has

direction and current and momentum. Through the use of parallel structures, coordinate

conjunctions, and subordinate clauses, the writer adds meaning, modifies, elaborates, and moves

from known to new information. Then sentences are conjoined to create paragraphs and the

paragraphs to produce a whole text. De Quincey (Masson, 1889) tells us The two capital secrets

in the art of prose composition are these: first the philosophy of transition and connection; or the

art by which one step in an evolution of thought is made to arise out of another; all fluent and

effective composition depends on the connections; secondly, the way in which sentences are

made to modify each other; for the most powerful effects in written eloquence arise out of this

reverberation, as it were, from each other in a rapid succession of sentences.

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 3

Neither of the secrets that De Quincey describes happen by chance. There exist rules or

contracts, acknowledged understandings that writers adhere to in order to produce text that is

fluent and effective. For example, consider the following: Every sentence following the topic

sentence in a coherent paragraph will usually include known information. Most frequently that

information will be in the subject position of the sentence; new information, the real purpose of

the sentence, will usually come in the predicate. Linguists have found this knownnew

sequence to be so persuasive a feature of prose that it has come to be called a contract. The writer

has an obligation, a contract of sorts, to fulfill expectations in the reader and keep the reader on

familiar ground by connecting each sentence in some way to what has gone before [Kolln,

1999]. This known-new contract is the basis of cohesion and sentence rhythm.

Creating Links Between Sentences and Between Paragraphs

Writers decide to link their sentences with explicit markers, or they decide not to make the link

explicit to readers. Sometimes a link is close by (local); sometimes it is separated by many pages

(global). Sometimes it must be inferred. The path of an authors thinking is marked by these

links, which must be understood by the reader (Langer, 1989). The links are rule-bound, not

idiosyncratic, since to be useful they must be logical and predictable. They make clear the

relationship between the ideas that the writer expects the reader to use in deciphering the texts

meaning. The most important linking structures are cohesive ties.

Cohesive ties fall into five major categories according to Halliday and Hasan (1976).

They are reference made up of personal pronouns, demonstratives, and comparative signals;

conjunction whose subcategories are additive, adversative, cause, and temporal; lexical cohesion

brought about by reiteration and collocation; ellipses, wherein parts of the sentence are left out;

and substitution wherein words are substituted for other structures.

Familiarity with a number of cohesive ties comes naturally to students through oral

language. It is not, for example, unusual to hear a 7- or 8-year-old recount her day by stringing

together a long series of events with and thens. Some of this oral language facility transfers to

writing, but some does not. For example, and then may come naturally, but on the other

hand certainly does not. Much of the actual function of cohesive ties becomes apparent only in

written text and then only when a teacher explains the concept.

Stephen P. Witte and Lester Faigley in 1981 examined the cohesion of low- and high-rated

essays. They found a significant difference in the frequency of ties. Even in the low group they

found a cohesive tie every 4.9 words: (20.4 percent of the words contributing to cohesion.) They

found an astonishing 31 percent in the high-rated essays. Marion Crowhurst (1987) examined

grade levels (6, 10, and 12) and modes (argument and narration), confirmed these high numbers

of total ties with frequencies between 20 and 25 percent at all levels.

A high percentage of the ties that Crowhurst found in narratives signaled time, especially

in the writing of sixth graders. The number of these temporal conjunctions decreased from grade

6 to 10 to 12, but that decrease was due largely to the decreasing frequency of the word then. That

one word accounted for 61 percent of the temporal conjunctions for sixth graders. And in

examining the temporal conjunctions used in argument, Crowhurst reports that even though total

numbers showed no significant difference between grades 6 and 12, word choice was decidedly

different. The sixth graders used only two temporal conjunctions: then and soon. Twelfth graders

developed their arguments with first of all, next, for one thing, meanwhile, all in all, and finally.

Crowhurst reports similar differences in the use of adversative conjunctions, with the sixth

graders relying mainly on but, and the twelfth graders using a much wider range.

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 4

Crowhurst reports that Halliday and Hasans categories of repetition, synonyms, and

collocation also showed significant differences for grade level, with synonyms and collocation

increasing with age: So, its apparent that knowledge of cohesive ties is an important tool for

writers to have.

Reading Comprehension

The role of text structures and cohesion in reading comprehension also important, and its

importance is not a new idea. In fact, the importance of cohesion was an idea afforded much

interest in the mid1980s. However, with its emphasis on the text, rather than the reader,

cohesion was not widely explored during the 1990s when the role of the reader and reading

strategies became the focus of research.

This importance of a students understanding of signal words (lexical ties) and text

structures to a students reading comprehension has been highlighted in Walter Kintschs (1988)

Construction-Integration Model. According to Kintsch, comprehension requires that readers

build a coherent representation of a text. That is, the reader must move through the text, taking in

and adding to information, deciding whats important, figuring out how one piece of information

relates to another (cohesion) and to what the reader already knows, and putting everything

together to develop meaning (coherence). To do this, Kintsch contends that a reader must

simultaneously construct what he calls a textbase and a mental model. Forming the first of these,

the textbase requires a reader to create an idea weban appropriate linkage of the idea units

(propositions) that the writer has put forth.

According to Kintsch, A propositionis used to represent the meaning of a (simple) sentence. A

text, at this level of representation, becomes a network of interconnected propositions.

Propositions are connected in various ways, by referential identityor by other relationships

among propositions, such as implied causal links. The resulting network of propositions is called

the microstructure of the text. The hierarchical macrostructure represents the global

organization of the text in sections and subsections, main points and minor digressions. Micro-

and macro structure together form the textbase. Fluent, cooperative readers usually form textbases

that closely mirror what the author had in mind when turning his or her ideas into words.

While the textbase (propositional level) represents the meaning and organization of the

text, the situation model can go far beyond the text itself. It is the readers understanding in terms

of his or her own goals, interests, and prior knowledge. Most importantly, it integrates the new

text and what the reader knew before by creating links between them. The textbase is a

symbolic, verbal structure; the situation model can be more general, including symbolic, verbal

elements as well as imagery of various kinds and emotional elements.

Notice in Kintschs model the importance of a readers being able to link propositions.

Notice, too, that the structures Kintsch specifies that link propositions are the same structures

used to build cohesion between sentences and coherence between paragraphs: referential

identityorother relationships among propositions, such as implied causal links.

In an effort to illustrate the prevalence of these ties in materials elementary students are

required to read, lets look at the first two paragraphs of a passage fourth grade readers are

required to comprehend for the grade 4 National Assessment of Educational Progress (Arnold,

2004). This is a passage identified as informational text though it begins with a narrative frame

and has several features typical of literary non-fiction, i.e., inverted sentence order and a first

person narrator (we).

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 5

Watch Out for Wombats!

As we rode along the highway sixty miles northeast of Adelaide, Australia, a diamond-shaped

sign suddenly loomed ahead. Watch Out for Wombats, it warned. We peered into the sparse scrub along

the roadside and searched for the brown furry animals. In the distance we spotted a mob of red

kangaroos bounding out of sight, and near the road a crow like bird called a currawong was perched, [but

nowhere did we see any wombats.] However, we later found out that this was not surprising because we

were traveling during midday, and wombats are active mostly at night. It wasnt until we visited the animal

reserve that we finally saw our first wombat and learned more about this funny-looking creature.

We found that there are two types of wombats in Australia: the hairy-nosed wombat, which lives

in Queensland and South Australia, and the coarse-haired wombat, which lives along the southeast

coast. Both have soft brown fur, short ears, and thick-set bodies. They are said to resemble North

American badgers. The hairy-nosed wombat is smaller and has pointier ears compared with its coarse-

haired cousin; otherwise they are very much alike.

When reading the paragraphs above, skillful readers will use a variety of comprehension

strategies simultaneously and effortlessly. They dip seamlessly into a reservoir of strategies that

can be called upon at the exact moment necessary to extract meaning from the text. Louise

Rosenblatt (1978) refers to a transaction between the reader and a text the reader response. The

text contributes a structure, genre, and content to the transaction, while the reader brings his or

her own prior knowledge, reading experiences, and values. When a reading transaction is fluid

and coherent, Rosenblatt calls the resulting, aesthetically pleasing outcome a poem, which is

also unique and personal to its reader. When a student no longer must struggle to decode

meaning from common passages, he or she becomes mentally free to form a personal response to

texts. The student is then able to experience reading as a poem, rather than simply a series of

obstacles. The same paragraphs below, now marked with arrows to show how readers may

struggle with text, remind us that the beauty of experiencing text as a poem remains elusive to

many readers.

As we rode along the highway sixty miles northeast of Adelaide, Australia, a diamond-shaped

sign suddenly loomed ahead. Watch Out for Wombats, it warned. We peered into the sparse scrub along

the roadside and searched for the brown furry animals. In the distance we spotted a mob of red

kangaroos bounding out of sight, and near the road a crow like bird called a currawong was perched, [but

nowhere did we see any wombats.] However, we later found out that this was not surprising because we

1 2 2a 3

4

5

6 7

8 9 10

11 12

14

15

16 17

1 2 2a 3

4

13

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 6

were traveling during midday, and wombats are active mostly at night. It wasnt until we visited the animal

reserve that we finally saw our first wombat and learned more about this funny-looking creature.

We found that there are two types of wombats in Australia: the hairy-nosed wombat, which lives

in Queensland and South Australia, and the coarse-haired wombat, which lives along the southeast

coast. Both have soft brown fur, short ears, and thick-set bodies. They are said to resemble North

American badgers. The hairy-nosed wombat is smaller and has pointier ears compared with its coarse-

haired cousin; otherwise they are very much alike.

Paragraph 1

At the beginning of the text, the reader encounters the pronoun we. This pronoun is exophoric,

not cohesive. It appears throughout the text. Next, but still in the first sentence the reader

encounters the word sign (1). The pronoun it (3) in sentence #2 refers back to sign (1) as does the

italicized Watch Out for Wombats (2).

The word Wombats (2a) is referenced further along by brown furry animals (4). This may

be a difficult link for readers who conceive of the italicized Wombats as part of a sign and not as

a distinct type of animal.

This (5) in sentence #5 refers back to the clause where did we see any wombats. And

creature (7) in the last sentence of the first paragraph refers back to wombat (6), the preceding

noun.

Paragraph 2

In paragraph 2, there is a chain of linkages. Hairy-nosed wombat (9) refers back to types (8) and

which (10) refers back to hairy-nosed wombats (9). Then course-hairy wombats (11) refer back

to types (8) and which (12) refers to coarse haired wombats (11). Both (13) refers back to types

(8). They (14) and they (17) refer back to both (13) and types (8). Hairy nosed wombat (15) is

modified by the comparatives smaller and pointier. Cousin (16) refers back to coarse-haired

wombat (11).

The most frequently employed kind of cohesive tie in this passage is called anaphora. Anaphora

is the linguistic term for a backward acting cue (such as a pronoun), which a reader must

decipher to understand the text. Sometimes the cue is close (local) and so relatively easy for a

reader to understand, as in the following:

8 9

10

11 12

13 14

15

16 17

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 7

(1) and (3): sign/it

(9) and (10): hairy-nosed wombat/which

(11) and (12): course-haired wombat/which

However, anaphoric links can also function to interweave and span quite long chunks of

text. In this case, the reference is global, rather than local, and may be considerably more

problematic to developing readers.

Writers also use longer anaphoric chains to create cohesion. The second paragraph of this

text contains a long anaphoric chain. This anaphoric chainsimply because of its lengthcould

confound a student who struggles to read.

As we rode along the highway sixty miles northeast of Adelaide, Australia, a diamond-shaped

sign suddenly loomed ahead. Watch Out for Wombats, it warned. We peered into the sparse scrub along

the roadside and searched for the brown furry animals. In the distance we spotted a mob of red

kangaroos bounding out of sight, and near the road a crow like bird called a currawong was perched, [but

nowhere did we see any wombats.] However, we later found out that this was not surprising because we

were traveling during midday, and wombats are active mostly at night. It wasnt until we visited the animal

reserve that we finally saw our first wombat and learned more about this funny-looking creature.

Further, anaphora may be problematic to readers when the same pronoun is used to refer

to two different nouns, as is the case with (9) and (10) and (11) and (12).

(2) and (4) and (6) and (7) represent another kind of link. In these two cases, the

reference is between nouns. In both pairs, one noun is more general than the other: (2) and (4):

animals/wombats and (6) and (7): wombat/creature.

Without question, this single example illustrates how understanding the passage requires

understanding the meaning of the ties. For most fourth graders, this understanding is not

problematic. They follow the meaning implicitly, having learned through oral language how

certain cohesive ties work. However, for othersELLs, students not routinely exposed to

academic or literary language, or struggling readers, the links do not facilitate making sense of

the text. If anything, they are confusing or meaningless.

It can be argued, then, that knowledge of cohesive ties is fundamental to both readers and

writers. Yet, in his 1983 work Reading Development and Cohesion, J ohn Chapman (1983) warns

us that one of the most surprising things that recent researchhas shown, is that full

1 2 2a 3

4

5

6 7

Copyright 2005, 2010 by Sally Hampton 8

understanding and the ability to use the ties that go to make up textural cohesion is still being

acquired well after the initial stages of learning to read. Mastery of some of the ties, as shown by

cloze tests, is only achieved by some pupils late in the secondary school. Yet the role of

cohesive ties is not often addressed in reading curricula.

In view of their importance to both reading and writing and to their prevalence in upper

grade texts, it would not seem unreasonable to suggest that the time has come for a closer

examination of the role of text structures and coherence and cohesion in facilitating reading

comprehension and writing development.

References

Arnold, C. (2004). Watch out for Wombats! NAEP 2004 sample reading questions: Grade 4.

Washington, DC: National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Chapman, L.J . (1983). Reading development and cohesion. London: Heinemann.

Connors, R.J ., & Lunsford, A.A. (1993). Teachers rhetorical comments on student papers.

College Composition and Communication, 44(2), 200223. doi:10.2307/358839

Crowhurst, M. (1987). Cohesion in argument and narration at three grade levels. Research in the

Teaching of English, 21, 185201.

Dornan, R.W., Rosen, L.M., & Wilson, M. (2003). Within and beyond the writing process in the

secondary English classroom. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Graham, S., & Harris, K.R. (1993). Improving the writing of students with learning problems:

Self-regulated strategy development. School Psychology Review, 22(4), 656671.

Halliday, M.A.K., & Hasan, R.K. (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Kintsch, W. (1988). The use of knowledge in discourse processing: A construction- integration

model. Psychological Review, 95, 163182. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.163

Kolln, M. (1999). Cohesion and coherence. In C.R. Cooper & L. Odell (Eds.), Evaluating

writing: The role of teachers knowledge about text, learning, and culture. Urbana, IL:

National Council of Teachers of English.

Langer, J .A. (1989). The process of understanding literature. Report Series 2.1. Albany: State

University of New York, Center for Learning and Teaching Literature.

Masson, D. (Ed.). (1889). The collected writings of Thomas De Quincey. Edinburgh: Adam and

Charles Black.

Rosenblatt, L.M. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary

work. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Tagg, J . (1986, March 16). Learning to think the write way. Los Angeles Times, p. 16.

van Dijk, T.A., & Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of discourse comprehension. New York:

Academic Press.

Witte, S.P., & Faigley, L. (1981). Coherence, cohesion, and writing quality. College

Composition and Communication, 32, 189204. doi:10.2307/356693

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- GRAMMAR Question FormationDocument4 pagesGRAMMAR Question FormationElena CMNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Primary English Learners Book 3 WebDocument28 pagesCambridge Primary English Learners Book 3 Webabdelazizsally72No ratings yet

- Heavy Machinery 14th June 2022Document6 pagesHeavy Machinery 14th June 2022Elmer Eduardo Mendoza BNo ratings yet

- Automata TheoryDocument19 pagesAutomata TheoryjayashreeNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Grammar in Language LearningDocument8 pagesThe Nature of Grammar in Language LearningNorbert Ian BatocaelNo ratings yet

- Morphology: The Study of Word StructureDocument20 pagesMorphology: The Study of Word StructuregiyatmiNo ratings yet

- ENG 426 Lecture 1: Defining MorphologyDocument3 pagesENG 426 Lecture 1: Defining MorphologyAmmar AnasNo ratings yet

- CLASS X-XI Integrated Grammar ExercisesDocument1 pageCLASS X-XI Integrated Grammar ExercisesBalvinder Kaur67% (15)

- Perfect Form of The Verbs in BracketsDocument1 pagePerfect Form of The Verbs in BracketsFacundo IbañezNo ratings yet

- Subjects Once and The Verbs Twice. Circle The Connectors. Then Indicate If The Sentences Are Correct (C) or Incorrect (I)Document3 pagesSubjects Once and The Verbs Twice. Circle The Connectors. Then Indicate If The Sentences Are Correct (C) or Incorrect (I)Somad BotNo ratings yet

- EFL Midterm Review ConceptsDocument4 pagesEFL Midterm Review ConceptsMohammedBaouaisseNo ratings yet

- Descriptive TextDocument5 pagesDescriptive TextMuhammad Bani BaihakiNo ratings yet

- Bound morpheme definitionDocument2 pagesBound morpheme definitionSyafiqah MatyusofNo ratings yet

- Exercise On Comparison of AdjectivesDocument5 pagesExercise On Comparison of AdjectivesMaryleNo ratings yet

- How To Solve ParajumblesDocument2 pagesHow To Solve ParajumblessushanthiNo ratings yet

- Coffee Break Italian-Travel Diaries-101-NotesDocument6 pagesCoffee Break Italian-Travel Diaries-101-Notespozitivnevibracije0% (1)

- Tos English 4Document1 pageTos English 4Val AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Passive Sentence Transformations B1 PETDocument2 pagesPassive Sentence Transformations B1 PETG100% (2)

- Example: I - in The Lake. (To Swim) Answer: I Swim in The LakeDocument5 pagesExample: I - in The Lake. (To Swim) Answer: I Swim in The LakeFrancisco SebastianNo ratings yet

- Romanian Verb ConjugationDocument9 pagesRomanian Verb ConjugationIulia Radu100% (2)

- Subject: English Class: 9th Form Duration: 3h Number of Student Review of Previous: DateDocument32 pagesSubject: English Class: 9th Form Duration: 3h Number of Student Review of Previous: DateBakaye DembeleNo ratings yet

- Verb (Syahid Al Faqih)Document4 pagesVerb (Syahid Al Faqih)Junita ManaluNo ratings yet

- Speculation Modals in PresentDocument15 pagesSpeculation Modals in PresentPaula RamirezNo ratings yet

- Subject Verb Agreement (Valenzuela, Joecelle, D)Document9 pagesSubject Verb Agreement (Valenzuela, Joecelle, D)Cella ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH SYNTAX AND MORPHOLOGYDocument126 pagesENGLISH SYNTAX AND MORPHOLOGYBull YangNo ratings yet

- 12th Grade Exam For 5th UnitDocument22 pages12th Grade Exam For 5th UnitОогий ОдгэрэлNo ratings yet

- How to Insert a SIM CardDocument15 pagesHow to Insert a SIM Cardanis jelitaNo ratings yet

- A2 ContentsDocument2 pagesA2 Contentsjuan carlos spilsbutyNo ratings yet

- CULTURES CUSTOMSDocument6 pagesCULTURES CUSTOMSselef1234No ratings yet

- A) Read The Following Sentences and Determine For Each If It Is Active or Passive VoiceDocument3 pagesA) Read The Following Sentences and Determine For Each If It Is Active or Passive VoiceMaria Pi0% (3)